Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To assess the safety and appropriateness of antibiotic use in adult patients with pharyngitis who opted for a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm vs patients who underwent a physician-directed clinical evaluation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes to query the electronic medical record database at our institution, a large multispecialty health care system in LaCrosse, WI, we identified adult patients diagnosed as having pharyngitis from September 1, 2005, through August 31, 2007. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome data were collected retrospectively.

RESULTS: Of 4996 patients who sought treatment for pharyngitis, 3570 (71.5%) saw a physician and 1426 (28.5%) opted for the nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm. Physicians adhered to antibiotic-prescribing guidelines in 3310 (92.7%) of 3570 first visits, whereas nurses using the algorithm adhered to guidelines in 1422 (99.7%) of 1426 first visits (P<.001). Physicians were significantly less likely to follow guidelines at patients' subsequent visits for a single pharyngitis illness than at their initial one (92.7% [3310/3570] vs 83.7% [406/485]; P<.001).

CONCLUSION: Instituting a simple nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm for patients presenting with pharyngitis appears to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use.

Instituting a simple nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm for patients presenting with pharyngitis appears to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use.

GABHS = group A β-hemolytic streptococcus; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; RADT = rapid antigen detection test

Pharyngitis, or sore throat, is one of the most common symptoms prompting people to seek medical care, accounting for 1% to 2% of all outpatient and emergency department visits in the United States.1,2 The vast majority of pharyngitis cases are of a viral etiology. Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis, accounting for 15% to 30% of cases in children and for 5% to 10% of cases in adults.3 Of the commonly occurring forms of acute pharyngitis, streptococcal pharyngitis is the only one for which antibiotic treatment is indicated.4 Other causes of bacterial pharyngitis that warrant antibiotic treatment (Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae) are much less common than streptococcal pharyngitis.3 Pharyngitis caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum, a common cause of pharyngitis in adolescents and young adults, may benefit from treatment to prevent the development of Lemierre syndrome. Groups C and G streptococci also cause pharyngitis, but the benefit of antibiotics for these pathogens is unknown.2,3

Treatment goals for streptococcal pharyngitis include not only symptom relief but also prevention of acute rheumatic fever, acute glomerulonephritis, and suppurative complications, such as peritonsillar abscess formation. Penicillin treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis is effective for prevention of acute rheumatic fever,1 with a number needed to treat for benefit of approximately 63, according to studies dating back to the 1950s.5 However, because the incidence of acute rheumatic fever decreased by roughly 60 times between 1965 and 1994, the current number needed to treat for benefit has likely greatly increased to approximately 3000 to 4000.1

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is a very rare complication of streptococcal pharyngitis, and no evidence has demonstrated that antibiotic treatment decreases its rate of occurrence. Peritonsillar abscess is also a very rare complication of streptococcal pharyngitis, and use of antibiotics for its prevention is controversial. Many of these patients (44%) develop this complication even before seeking medical care,1 and the causes of peritonsillar abscesses are typically polymicrobial, with organisms less likely to be effectively treated with antibiotics recommended for GABHS. In 1 study, only 25% of patients who developed peritonsillar abscesses had a culture or rapid antigen detection test (RADT) positive for GABHS, and 67% had previously been treated with antibiotics typically used for GABHS infections.6

Antibiotic use for confirmed streptococcal pharyngitis has been shown to reduce symptom duration by only 1 to 2 days. Nationally, antibiotics were prescribed in 73.0% of adults with sore throats between 1989 and 1999, a percentage that greatly exceeds the expected prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis in this population.7 Antibiotics not recommended for streptococcal pharyngitis were prescribed in 68% of treated patients.

Inappropriate antibiotic use has adverse medical consequences and contributes to microbial antibiotic resistance.8 Therefore, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) adopted strict guidelines for the treatment of acute pharyngitis, which include laboratory confirmation of GABHS infection with either RADT or throat culture before antibiotics are prescribed.4 Our institution adopted this strategy when developing its own guidelines for managing acute pharyngitis. Our guidelines also offer patients aged 2 years or older who visit urgent care for a sore throat the option to forego being seen by a physician and instead to be seen under a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm.

The purpose of this study was to assess the safety and appropriateness of antibiotic use in adult patients (≥18 years) who opted for the nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm vs patients who underwent a physician-directed clinical evaluation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Our institution is a large multispecialty health care system headquartered in La Crosse, WI, comprising nearly 700 medical, dental, and associate staff. In 2008, the system had over 1.3 million outpatient clinic visits, 24,000 emergency department visits, and 14,000 inpatient admissions.

After approval by the Gundersen Lutheran Institutional Review Board, we performed a retrospective cohort study on diagnosed cases of pharyngitis in patients 18 years or older. Using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes 034.0 and 462, we identified all patient encounters in our institution's adult urgent care, emergency department, family practice clinics, general internal medicine clinics, and internal medicine resident clinics resulting in a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, sore throat, or pharyngitis from September 1, 2005, through August 31, 2007. Encounters were excluded from further analysis if the patient had multiple diagnoses to rule out the possibility that antibiotics had been prescribed for the alternative diagnosis rather than for the sore throat. Encounters also were excluded from the study if antibiotics were prescribed for a condition other than pharyngitis (eg, a urinary tract infection).

Electronic medical records corresponding to each clinic visit were reviewed by a trained research associate. From the medical record, the following data were extracted: visit number (ie, visit 1 or more for the same sore throat); location of the visit; RADT and throat culture data, if any; and whether the patient saw a physician or opted for the nurse-only treatment algorithm. Average billing data were also collected. In cases in which the research associate had questions regarding the clinical data, additional review was performed by 1 of the physician authors (D.K.U., T.J.K.) to ensure accuracy.

Definitions

We defined antibiotics to have been prescribed appropriately only if a throat culture or RADT was positive for GABHS. We defined antibiotics to have been prescribed inappropriately if they were (1) prescribed in the absence of laboratory confirmation (even if subsequent throat cultures were positive for GABHS) or (2) not prescribed when the RADT or throat culture was positive for GABHS.

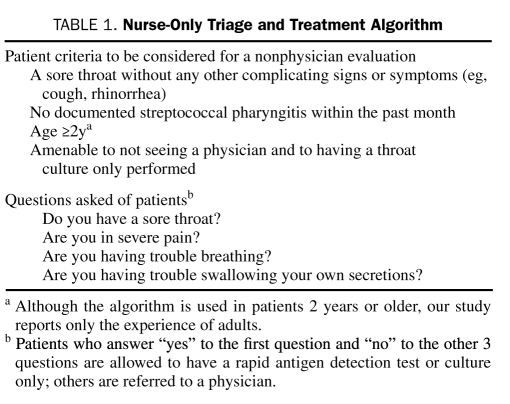

Patients who visited urgent care with pharyngitis were given the option of a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm, which confirmed the presence of a sore throat as the primary symptom and identified potential complications that would necessitate physician evaluation. Patients who chose this option and met criteria underwent RADT; if findings were negative for GABHS, a throat culture was reflexively performed. Patients with findings positive for GABHS on RADT or throat culture were to be treated with antibiotics. Table 1 summarizes the nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm used in our urgent care department. Antibiotics were prescribed on the basis of RADT and throat culture results without input from the physician as to whether to prescribe antibiotics.

TABLE 1.

Nurse-Only Triage and Treatment Algorithm

Statistical Analyses

To determine whether there were any differences by physician specialty or location of evaluation, antibiotic prescription practices were analyzed by 4 subgroups: (1) emergency department and urgent care, (2) internal medicine clinics, (3) family practice clinics, and (4) internal medicine resident physicians. We also assessed whether the prescribing practices of resident physicians differed by year of residency training. Prescribing practices at the initial vs subsequent patient encounters were also compared, because patients often made multiple visits for the same sore throat. Finally, the prescribing practices of physicians were compared with those of nurses who used the triage and treatment algorithm.

Statistical comparisons of all groups were performed using χ2 tests. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. For the comparison of rates of guideline adherence between first and second visits, the P value holds when the dependency from repeated observations per patient is resolved; for ease of reading we report the unadjusted rates.

RESULTS

Inclusion criteria were met by 4996 unique patients, some of whom were seen multiple times for the same sore throat, for a total of 5569 visits.

First Visit

Of the entire cohort of 4996 patients with pharyngitis, 4732 (94.7%) were treated appropriately (as defined in Patients and Methods) during their first visit for sore throat. Antibiotics were appropriately prescribed in 1422 (99.7%) of 1426 patients treated under the nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm and 3310 (92.7%) of 3570 patients evaluated by physicians (P<.001).

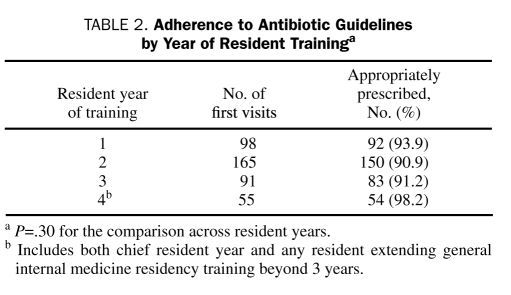

Appropriate antibiotic use was similar among family practice physicians (580/632; 91.8%), internal medicine physicians (200/211; 94.8%), internal medicine residents (379/409; 92.7%), and emergency/urgent care physicians (2151/2318; 92.8%) (P=.53). No significant differences in appropriate prescription practices were noted among resident physicians by year of training (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines by Year of Resident Traininga

Antibiotics were prescribed for 837 of the 3570 patients seen by a physician during their first visit for sore throat, for an overall prescription rate of 23.4%. However, the percentage of documented cases of streptococcal infection among those in whom an RADT or throat culture was performed was 19.4% (614/3161). Antibiotics were prescribed at a higher rate than documented cases of streptococcal infection, because 250 (29.9%) of 837 antibiotic courses were prescribed inappropriately (as defined in Patients and Methods). Of the 250 inappropriate prescriptions, 92 (36.8%) were prescribed despite having no RADT or culture performed; 135 (54%) were prescribed despite RADT or culture negative for infection; and 23 (9.2%) were prescribed before culture results positive for infection were available.

Four of the 1426 patients treated under the algorithm were treated inappropriately. Two (50%) received antibiotics because of an exposure to a family member positive for streptococcal infection, and 1 (25%) received antibiotics via a verbal order from a physician obtained by the nurse seeing the patient. For the remaining patient (25%), findings for group A streptococci were negative on RADT but positive on throat culture. However, according to the medical record, no antibiotics were prescribed for this patient.

Second Visits

Of the 1426 patients initially treated under the algorithm, 145 (10.2%) returned for either persistent or worsening sore throat symptoms or for medication-related adverse effects. Of these patients, 5 (3.4%) were subsequently diagnosed as having mononucleosis; 3 (2.1%) had new symptoms, were diagnosed as having sinusitis, and were treated with antibiotics; 1 (0.7%) had developed thrush, for which treatment was prescribed; and 2 (1.4%) had subsequent laboratory confirmation of GABHS infection and were prescribed antibiotics. On re-presentation, 1 patient (0.7%) was diagnosed as having likely viral myopericarditis. Three (2.1%) underwent tonsillectomy in the months after their initial presentation, 2 (1.4%) for recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis, and 1 (0.7%) for an enlarged tonsil that was found to be benign tonsillar lymphoid hyperplasia. The remainder of the patients who re-presented (127/145; 87.6%) were either treated symptomatically, prescribed antibiotics inappropriately, or had their antibiotic changed for persistent symptoms.

Of the 3570 patients first seen by physicians, 340 (9.5%) returned for persistent symptoms or medication-related adverse effects, a return rate similar to that of patients first seen under the algorithm (145/1426;10.2%; P=.49).

Patients were significantly less likely to be appropriately prescribed antibiotics during their second visit than they were during their first. Antibiotics were appropriately prescribed in 83.7% (406/485) of the patients who returned for a second visit for unresolved symptoms of sore throat vs 92.7% (3310/3570) of patients during their first visit (P<.001).

Cost

Patients seen by a physician were billed an average of $211 per visit, whereas those seen under the triage and treatment algorithm were billed an average of $76 per visit.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective observational study of antibiotic-prescribing patterns for adults with pharyngitis shows that a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm for patients with sore throat seems to be safe and cost-effective. Prior studies indicated that antibiotics were prescribed in 73.0% of adults presenting with sore throats between 1989 and 1999.7 Our study found a much lower rate of antibiotic prescription (23.4%; 837/3570), most instances of which were appropriate as we defined it for our study. However, the overall antibiotic prescription rate of 23.4% (837/3570) still exceeded the percentage of confirmed streptococcal pharyngitis cases, which was 19.4% (614/3161) among those tested.

We found no major differences between the prescribing habits of internal medicine residents and physicians from family practice clinics, internal medicine clinics, or urgent care/emergency departments. Further, residents' antibiotic-prescribing practices did not differ by year of training.

The triage and treatment algorithm performed very well in this study. Patients treated via the algorithm were more likely than those seen by physicians to be treated appropriately as we have defined it. Fewer patients treated according to the algorithm received antibiotics inappropriately, so fewer were exposed unnecessarily to antibiotic-related adverse effects. Our review of medical records revealed no instances in which a diagnosis that might have been made sooner under physician evaluation was missed, with the exception of 5 cases of mononucleosis, the treatment of which is primarily supportive, except for the recommended activity restrictions to avoid traumatic splenic rupture. The average bill of the patients treated via the algorithm was lower. Therefore, evaluating adult patients via a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm appears to be a safe, accurate, and cost-effective method of managing adult patients with sore throats.

Physicians were less likely to adhere to the treatment guideline when patients made a subsequent visit to be evaluated with continued, unresolved symptoms. Physicians adhered to our institution's pharyngitis antibiotic-prescribing guidelines 92.7% (3310/3570) of the time at patients' first visit for sore throat, an encouraging rate of appropriate antibiotic prescription, but this percentage fell to 83.7% (406/485) for a patient's second visit. No published guidelines or evidence support the use of antibiotics in patients whose sore throat symptoms persist despite conservative treatment when RADTs or throat cultures are negative for GABHS or when an alternative bacterial pathogen is absent. None of the records of the patients who returned for follow-up evaluation indicated the diagnosis of an alternative bacterial etiology for pharyngitis (eg, Arcanobacterium spp, Fusobacterium spp) as the rationale for antibiotic therapy; however, medical record reviews are limited in their ability to discern a physician's treatment rationale.

Physicians report that they prescribe unwarranted antibiotics because patients expect to be prescribed antibiotics, because patients bounce from physician to physician if antibiotics are not prescribed, and because it is quicker to write a prescription than to explain why the antibiotics are not indicated.9 The harm of overprescribing antibiotics has been well documented.8 Increased use of pharyngitis triage and treatment algorithms may be a tool to minimize inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions in patients who present with sore throat. First, algorithms such as the one described here can be used to educate patients early in the encounter that the prescription of antibiotics is a function of a positive diagnostic test for GABHS. Second, because a physician encounter is not required for this algorithm, physicians cannot be tempted to prescribe antibiotics rather than take the time to explain why they are unnecessary. Inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions expose patients to antibiotics' common adverse effects, such as allergic reactions or intolerances, and their normal microbial flora is changed, putting them at increased risk for opportunistic infections (eg, infections with Clostridium difficile, yeasts, or antibiotic-resistant organisms).8

Widely applying a similar nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm may be a strategy to substantially reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for pharyngitis. In our practice, the rate of the appropriate use of antibiotics for this patient population was high. However, such a high rate of appropriate antibiotic use is uncommon in the published literature.1,3,4,7 The anticipated reduction in inappropriate antibiotic use would be substantial if our algorithm were applied to populations with such significantly higher rates of inappropriate antibiotic use.

Our study has limitations, primarily those inherent to retrospective studies. First, no single set of guidelines exists regarding appropriate prescription of antibiotics for patients with pharyngitis. In accordance with our institutional and IDSA guidelines, we considered the prescription of antibiotics to be appropriate only when GABHS infection was confirmed by laboratory testing; however, other guidelines rely instead on clinical criteria to gauge a patient's likelihood of having streptococcal pharyngitis and, in turn, to decide whether to prescribe antibiotics. Second, a potential for selection bias exists between patients who chose to be seen under the nurse algorithm rather than by a physician. Patient characteristics, severity of illness, and expectations regarding the need for antibiotics might have been different in patients willing to forego physician evaluation in favor of the nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm. However, our study described a real-world scenario that may enhance its generalizability to other institutions. Third, because our study was focused on primary care physicians and walk-in care rendered in urgent care and emergency settings, our results may not necessarily extrapolate to other patient populations. Finally, some patients treated in accordance with the pharyngitis triage and treatment algorithm may have received throat cultures that would not have been ordered by a physician. Nonetheless, we consider this possible disadvantage to be outweighed by the greater adherence to the appropriate prescription of antibiotics under the algorithm.

CONCLUSION

Instituting a simple nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm for patients presenting with sore throat showed great promise in our study as a tool to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. With the implementation of the algorithm, practices with higher baseline rates of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions for pharyngitis would likely see even greater improvements in antibiotic stewardship than those reported here. Future prospective trials to document the safety and efficacy of this approach are warranted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(6):711-719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humair JP, Revaz SA, Bovier P, Stalder H. Management of acute pharyngitis in adults: reliability of rapid streptococcal tests and clinical findings. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(6):640-644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisno AL, Peter GS, Kaplan EL. Diagnosis of strep throat in adults: are clinical criteria really good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(2):126-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH, Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(2):113-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denny FW, Wannamaker LW, Brink WR, Rammelkamp CH, Jr, Custer EA. Prevention of rheumatic fever: treatment of the preceding streptococcic infection. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143(2):151-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb KH, Needham CA, Kurtz SR. Use of a high-sensitivity rapid strep test without culture confirmation of negative results: 2 years' experience. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(1):34-38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder JA, Stafford RS. Antibiotic treatment of adults with sore throat by community primary care physicians: a national survey, 1989-1999. JAMA. 2001;286(10):1181-1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linder JA. Antibiotics for treatment of acute respiratory tract infections: decreasing benefit, increasing risk, and the irrelevance of antimicrobial resistance [editorial]. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):744-746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler CC, Rollnick S, Pill R, Maggs-Rapport F, Stott N. Understanding the culture of prescribing: qualitative study of general practitioners' and patients' perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. BMJ. 1998;317(7159):637-642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]