Abstract

Aromatic–aromatic interactions are a most prominent feature of the crystal structure of ELIC (PDB code 2VL0), a bacterial member of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily of ion channels where five pore-facing phenylalanines come together to form a structure akin to a narrow iris that occludes the transmembrane pore. To identify the functional state of the channel this structure represents, we engineered phenylalanines at various pore-facing positions of the muscle acetylcholine receptor (one position at a time), including the position that aligns with the native phenylalanine 246 of ELIC, and assessed the consequences of such mutations using electrophysiological and toxin-binding assays. From our experiments, we conclude that the interaction among the side chains of pore-facing phenylalanines, rather than the accumulation of their independent effects, leads to the formation of a non-conductive conformation that is unresponsive to the application of acetylcholine and is highly stable even in the absence of ligand. Moreover, electrophysiological recordings from a GLIC channel (another bacterial member of the superfamily) engineered to have a ring of phenylalanines at the corresponding pore-facing position suggest that this novel refractory state is distinct from the well-known desensitized state. It seems reasonable to propose, then, that it is in this peculiar non-conductive conformation that the ELIC channel was crystallized. It seems also reasonable to propose that, in the absence of rings of pore-facing aromatic side chains, such stable conformation may never be attained by the acetylcholine receptor. Incidentally, we also noticed that the response of the proton-gated, wild-type GLIC channel to a fast change in pH from 7.4 to 4.5 (on the extracellular side) is only transient, with the evoked current fading completely in a matter of seconds. This raises the possibility that the crystal structures of GLIC obtained at pH 4.0 (PDB code 3EHZ) and 4.6 (PDB code 3EAM) correspond to the to the (well-known) desensitized state.

Keywords: Cys-loop receptors, aromatic–aromatic interactions, desensitization, electrophysiology, patch-clamp

INTRODUCTION

Although the number of high-resolution structural models of membrane proteins continues to grow, our ability to associate structures with well-defined functional states lags far behind. Frequently, this is due to the incomplete understanding of the conformational dynamics of the protein in question (even in its native membrane microenvironment), a problem that is aggravated by the possibility that experimental artifacts (such as the effect of detergents1,2 or of forces developing within the crystal3) shift the equilibrium among conformations in hard-to-predict ways. In some other cases, structural data come from a given protein whereas functional information is available for a distantly related ortholog, raising the inevitable question as to the extent to which the two sets of data can be compared.

The crystal structure of ELIC, a bacterial member of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily4 whose conformational dynamics are still uncharacterized, was recently solved5 (3.3 Å resolution; PDB code 2VL0) and proposed as a model for the entire superfamily. Perhaps because the transmembrane portion of the ion-permeation pathway is occluded near its extracellular end (minimum pore radius ≅ Na+ radius ≅ 1.0 Å; Fig. 1), this structural model was identified as the closed-channel conformation and was subsequently used to infer a mechanism for the closed ⇄ open, gating conformational change6,7. But another structural model of the closed conformation of a nicotinic receptor, generated on the basis of 4.0-Å resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) data from the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) of Torpedo’s electric organ (a muscle-type AChR) in the absence of activating ligands, features a much wider pore with a minimum radius of ~2.5–3.0 Å at the center of the membrane8 (Fig. 1a). Thus, while the occluded pore of ELIC suggests that the closed ⇌ open gate poses a steric barrier to the permeation of ions, the model of Torpedo’s AChR posits that this gate presents a desolvation penalty, instead9–11 (radius of Na+ with the innermost hydration shell ≅ 3.0 Å; Ref. 12), clearly, two very different mechanisms for the same phenomenon.

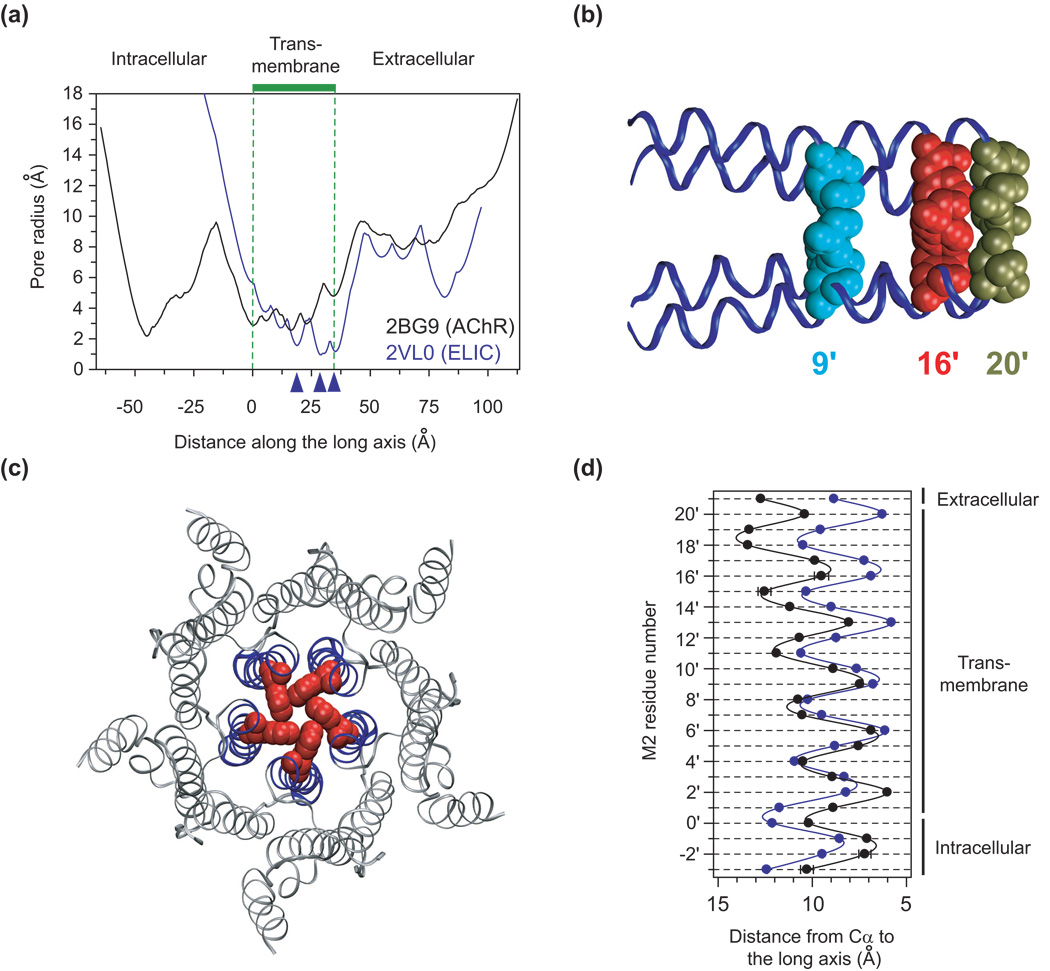

Figure 1. Structural aspects of two nicotinic type-receptor models.

(a) Pore-radius profiles calculated using the HOLE program31 for PDB files 2VL0 (the ELIC channel5) and 2BG9 (the AChR from Torpedo’s electric organ8). The three blue arrowheads indicate the approximate locations of the three most constricted regions of the pore of ELIC. (b) Detail of the transmembrane pore of ELIC with the five side-chains of leucine 239 (cyan; position 9′), phenylalanine 246 (red; 16′) and asparagine 250 (tan; 20′) shown in van der Waals representation. The backbones corresponding to the pore-lining M2 segments are shown in ribbon representation. The backbone of the subunit facing the viewer was removed for clarity. (c) Graphical representation of the transmembrane portion of the pore of ELIC as viewed from the extracellular side. Backbones are shown in ribbon representation (M2 in blue; M1, M3 and M4 in gray). The five side chains of phenylalanine 246 are shown in van der Waals representation (red). The mean (and standard error) distance between adjacent phenylalanine side-chain centroids is 4.33 Å (± 0.03 Å). (d) Two-dimensional representation of the M2 backbones of ELIC and the AChR. The color code is the same as in (a). The lumen of the pore is to the right of the plot. The difference in tilt angle of the M2 α-helices corresponding to the two structural models can be appreciated. The residues of ELIC were aligned with those of the AChR in such a way that ELIC’s arginine 230 corresponds to the conserved basic residue at position 0′ of the metazoan members of the superfamily (and hence, phenylalanine 246 aligns with position 16′). On the basis of the structure of ELIC, the two most intracellular pore-facing residues of the AChR’s M2 α-helices are tentatively considered to be those occupying positions −2′ and −1′ (rather than 2′ and 3′, as in the 2BG9 model). Means and standard errors were calculated from the values corresponding to the five individual subunits, and the unbroken lines are cubic-spline interpolations. The molecular images were made, and distances were measured, using VMD32.

Evidently, the resolution of the crystal structure (3.3 Å) is much better than that of the cryo-EM images (4.0 Å), but equally evident is the fact that the amino-acid sequence of the AChR from Torpedo is much closer to the sequences of the functionally best-characterized members of the superfamily (such as the mouse- or human-muscle AChR) than is any of the sequences from bacterial or archaeal origin described to date. So which model provides a more appropriate structural framework for interpreting the existing wealth of functional data?

The ion-permeation pathway of ELIC is occluded because five pore-facing phenylalanines (phenylalanine 246), one per subunit, come together in a nearly T-shaped, edge-to-face arrangement13 to form a structure akin to a narrow iris (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). Two other rings of pore-facing residues, the leucines at position 239 and the asparagines at position 250 (Supplementary Fig. 1), flank the phenylalanines at position 246 and contribute two additional constrictions (Fig. 1b), but the pore of ELIC is narrowest at the level of the central ring of phenylalanines (Fig. 1a; note that, throughout the paper, we use the term “ring” to denote the arrangement of pore-facing atoms around the long axis of the channel rather than to refer to the benzene ring-like properties of the aromatic side chains). Owing to the low identity, there is some ambiguity in the alignment of primary sequences, but we favor the notion that positions 239, 246 and 250 of ELIC correspond to the 9′, 16′ and 20′ positions, respectively, of the second transmembrane segment (M2) of the, better-understood, metazoan members of the superfamily (Supplementary Fig. 1; others, however, have proposed that the ring of phenylalanines at position 246 aligns with position 20′; for example, Ref. 5).

Importantly, an inspection of sequenced genomes reveals that full rings of aromatic residues are not predicted to occur in vertebrate members of the superfamily at the 16′ or at any other pore-facing position, and that even the GLIC channel (a bacterial, proton-gated homolog14 whose structure has also been determined by X-ray crystallography6,7) has an aliphatic residue at the aligned position4 (Supplementary Fig. 1). On the other hand, the amino acids forming the other two constrictions are not unique at all. Indeed, the leucine at position 239 of ELIC aligns with the very well conserved leucine 9′ of metazoan members of the superfamily, and the polar asparagine at position 250 aligns with the “extracellular ring of charge” (first identified in the AChR from Torpedo15), which mainly contains asparagine, glutamine and ionizable residues.

Admittedly, despite the very low sequence identity between ELIC and the AChR from Torpedo, many structural and functional features are remarkably well conserved; after all, ELIC is a bona fide member of the Cys-loop receptor superfamily even when lacking the signature cysteine loop. But it is conceivable that some sequence differences may have a more profound impact on structure and function than others. Therefore, we decided to focus on the central phenylalanines. Specifically, we asked how relevant the “aromatic plug” of ELIC and its mechanistic implications are for members of the superfamily that lack full rings of aromatic side chains at pore-facing positions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Aromatic–aromatic interactions favor a nonconductive conformation

We engineered a full ring of phenylalanines at position 16′ of the well-characterized, muscle (adult-type) AChR and assessed the functional consequences of such mutations using a variety of electrophysiological and toxin-binding assays. The most salient effect of the presence of this ring of pore-facing aromatic side chains was a marked decrease in the peak amplitude of the ensemble (“macroscopic”) currents elicited in response to step applications of nearly saturating concentrations of ACh to outside-out patches. Indeed, whereas the average peak amplitude was 1.95 ± 0.4 nA (16 patches) for the wild-type AChR (which contains only one phenylalanine in the 16′ ring; Supplementary Fig. 1), this value was 0.05 ± 0.01 nA (17 patches) for the mutant with five phenylalanines in the ring.

The peak of the macroscopic response is a function of the current through each individual AChR at the assayed membrane potential (here, −80 mV), the probability of the channel being open at the peak of the current transient (the “peak open probability”) and the number of readily activatable channels in the patch. Thus, several different phenomena could account for the observed reduced response, including a reduced single-channel conductance, a reduced closed ⇌ open gating equilibrium constant, a slower rise time, faster kinetics of entry into desensitization and a lower level of channel expression on the plasma membrane. However, analysis of macroscopic and single-channel currents recorded under a variety of experimental conditions, along with the estimation of α-bungarotoxin binding sites on the plasma membrane of transfected cells, revealed that none of the aforementioned effects is of enough magnitude, or even occurs in the right direction, so as to underlie the ~40-fold decrease in the response of the full phenylalanine-ring mutant to ACh. Certainly, the rise time of the macroscopic currents through the mutant is indistinguishable from the wild-type value, the mutant’s peak open probability (estimated from single-channel recordings, as indicated in Materials and Methods) is slightly larger (by a factor ~1.1; see also Supplementary Fig. 2), the amplitude of the mutant’s single-channel currents is lower by a factor of only ~1.4, and the level of receptor expression on the plasma membrane is lower for the mutant by a factor of only ~2.4 (Table 1). Together, these small differences can only account for a ~3-fold decrease in the peak response. Furthermore, although the mutant’s time constant of entry into desensitization is shorter than the wild type’s (by a factor of ~1.6; Table 1), desensitization is still not fast enough in the mutant to account for the highly reduced response to ACh (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Effect of phenylalanine substitutions at pore-facing positions 16′ or 20′ of the AChR

| M2 position |

Number of phenylalanines |

Peak current (nA)a |

Single-channel current (pA) |

Normalized surface expression |

Open probability within clusters |

τdeactivation (ms) | τdesensitization (ms) | τrecovery (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16′ | 0 | 1.91 ± 0.39 (4) | 5.66 ± 0.34 (3) | 1.08 ± 0.09 (4) | 0.93 ± 0.004 (2) | 1.52 ± 0.31 (4) | 24 ± 4 (4) | 181 ± 54 (3) |

| 1 (β1) | 1.28 ± 0.45 (13) | 5.37 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.31 ± 0.09 (4) | 0.93 ± 0.007 (3) | 3.34 ± 0.53 (8) | 111 ± 13 (12) | 540 ± 90 (5) | |

| 1 (δ) | 1.46 ± 0.48 (8) | 5.41 ± 0.13 (3) | 0.27 ± 0.03 (4) | 0.96 ± 0.01 (4) | 1.58 ± 0.19 (6) | 37 ± 4 (8) | 452 ± 107 (4) | |

| 1 (ε) (wild type) | 1.95 ± 0.40 (16) | 5.66 ± 0.06 (4) | 1.0 | 0.85 ± 0.002 (3) | 1.09 ± 0.20 (5) | 34 ± 6 (6) | 191 ± 33 (4) | |

| 2 (2α1) | 0.50 ± 0.13 (12) | 4.68 ± 0.47 (3) | 0.64 ± 0.07 (4) | 0.95 ± 0.005 (5) | 4.56 ± 0.53 (11) | 85 ± 14 (12) | 436 ± 101 (7) | |

| 5 (2α1, β1, δ, ε) | 0.05 ± 0.01 (17) | 3.97 ± 0.14 (4) | 0.41 ± 0.03 (12) | 0.97 ± 0.005 (5) | 6.19 ± 1.40 (6) | 21 ± 4 (5) | ---b | |

| 20′ | 0 (wild type) | 1.95 ± 0.40 (16) | 5.66 ± 0.06 (4) | 1.0 | 0.85 ± 0.002 (3) | 1.09 ± 0.20 (5) | 34 ± 6 (6) | 191 ± 33 (4) |

| 1 (β1) | 0.74 ± 0.24 (11) | 6.10 ± 0.08 (2) | 0.52 ± 0.03 (4) | 0.40 ± 0.05 (4) | 1.68 ± 0.20 (9) | 78 ± 16 (8) | 391 ± 87 (8) | |

| 1 (δ) | 1.14 ± 0.64 (7) | 5.83 ± 0.46 (2) | 0.56 ± 0.03 (3) | 0.93 ± 0.007 (4) | 3.20 ± 0.27 (7)c | 316 ± 63 (6) | 519 ± 110 (6) | |

| 1 (ε) | 0.80 ± 0.19 (14) | 5.68 ± 0.09 (3) | 0.60 ± 0.05 (4) | 0.76 ± 0.06 (4) | 1.40 ± 0.24 (12) | 170 ± 38 (14) | 340 ± 85 (6) | |

| 2 (2α1) | 0.37 ± 0.19 (5) | 5.07 ± 0.09 (2) | 0.63 ± 0.07 (4) | 0.66 ± 0.03 (4) | 0.58 ± 0.10 (5) | 80 ± 23 (5) | 478 ± 117 (3) | |

| 5 (2α1, β1, δ, ε) | 0 (>15) | ---b | 0.21 ± 0.03 (6) | ---b | ---b | ---b | ---b | |

Throughout the table, the number of individual experiments analyzed for each parameter (one experiment per patch of membrane) is indicated in parentheses. The number of clusters analyzed for column 6 varied among experiments and ranged between 25 and 1,789.

Not determined (see text).

A second exponential component with time constant τ2 = 66 ± 13 ms and relative amplitude a2, rel = 2.4 ± 0.7 % was required to fit the data.

Thus, we are left with the intriguing possibility that only a small fraction of the mutant receptors in the membrane can actually open upon exposure to ACh; the rest must be in some sort of refractory, highly stable non-conductive conformation. We are not aware of any other type of mutation that causes the AChR or other members of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily to adopt a conformation of similar properties.

To gain insight into the structural underpinnings of this most unusual phenotype, we compared the peak-current response of the AChR having phenylalanines in all five subunits (at position 16′) with the peak values corresponding to the channels with phenylalanines in single subunits after normalization of these currents to account for the minor differences in single-channel current amplitude, peak open probability and channel-expression level (“normalized current densities” in Figs. 2 and 3). As shown in Fig. 2a, our data indicate that the lower peak amplitude observed for the full-ring mutant (indicated by the bright-red bar) results from the interaction among the five phenylalanines in the ring rather than from the simple accumulation of the effect of these aromatic residues on individual subunits. Certainly, if the five engineered phenylalanines contributed independently to function, then the normalized current density of the mutant with the full ring of phenylalanines would be expected (on the basis of the properties of the mutants with phenylalanines in single subunits) to be larger than the value we actually recorded by a factor of ~55 (compare the bright-red and light-red bars); this is compelling evidence for the non additivity of the effect of the engineered phenylalanines.

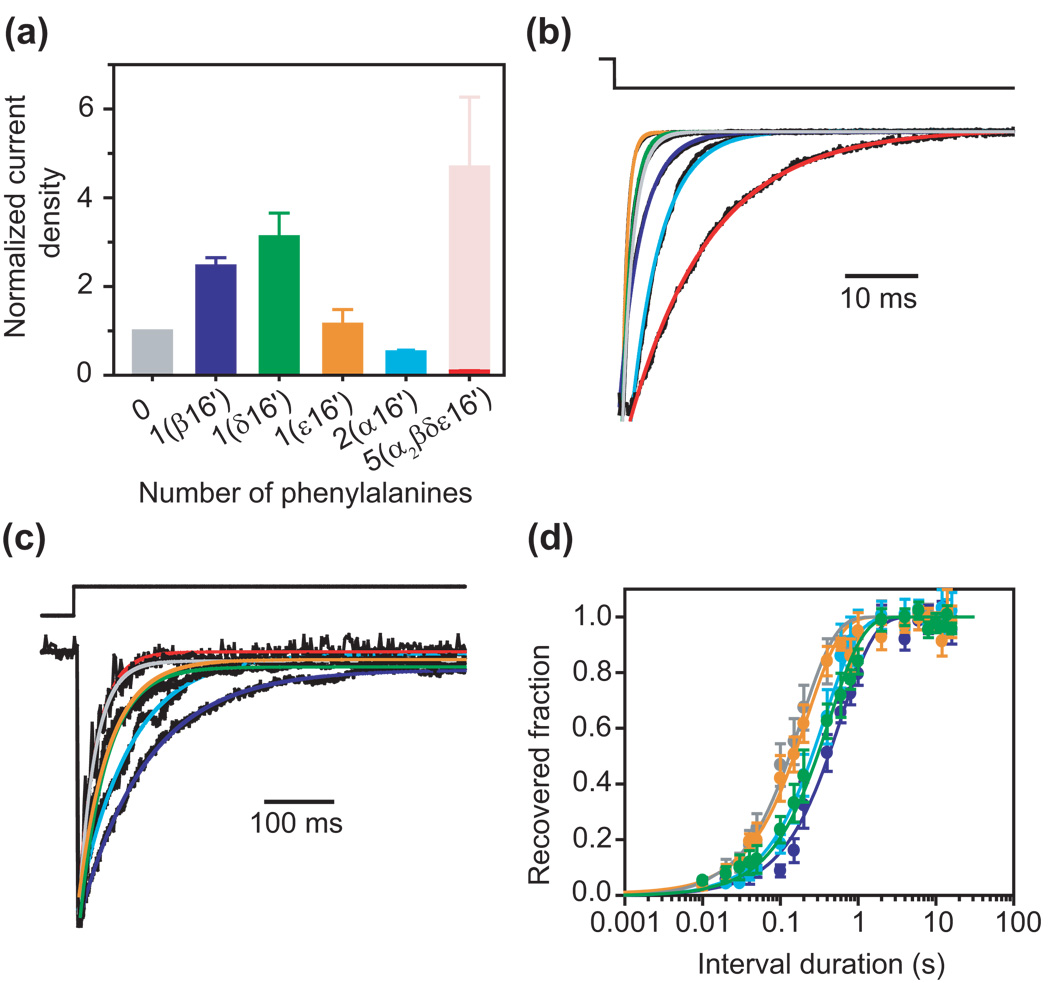

Figure 2. Effect of phenylalanine substitutions at position 16′.

(a) Normalized current densities. The average peak value of the current transients elicited by the step application of a nearly saturating concentration of ACh (100 µM) was divided by the single-channel current amplitude, the intracluster open probability and the channel-expression level (see Table 1). These current densities were, in turn, normalized to that of the AChR having a full ring of leucines at position 16′ (that is, the εF268L mutant). The bright-red bar indicates the (experimentally determined) current density corresponding to the mutant with a full ring of phenylalanines at position 16′, whereas the light-red bar in its background indicates the (calculated) value that would be expected if the five phenylalanines contributed independently to this mutant’s phenotype. The number of phenylalanines in the 16′ ring, and the subunit(s) bearing this aromatic residue, are indicated. Error bars are standard errors calculated by propagating the standard errors of the individual parameters. (b) Kinetics of deactivation. Each plotted trace is the average response of an outside-out patch to 25 brief pulses of 100-µM ACh applied as a low-frequency train. The color code is the same as in (a). (c) Kinetics of entry into desensitization. Each plotted trace is the response of an outside-out patch to a long pulse of 100-µM ACh; only the first ~550 ms are shown. The color code is the same as in (a). (d) Kinetics of recovery from desensitization estimated using pairs of pulses of 100-µM ACh. Error bars are standard errors calculated from the results of several independent experiments (one experiment per patch). The color code is the same as in (a). In the case of the full phenylalanine-ring mutant, the low amplitude of the currents made the responses to this paired-pulse protocol highly unreliable, and hence, these data are not included. All estimated time constants are given in Table 1.

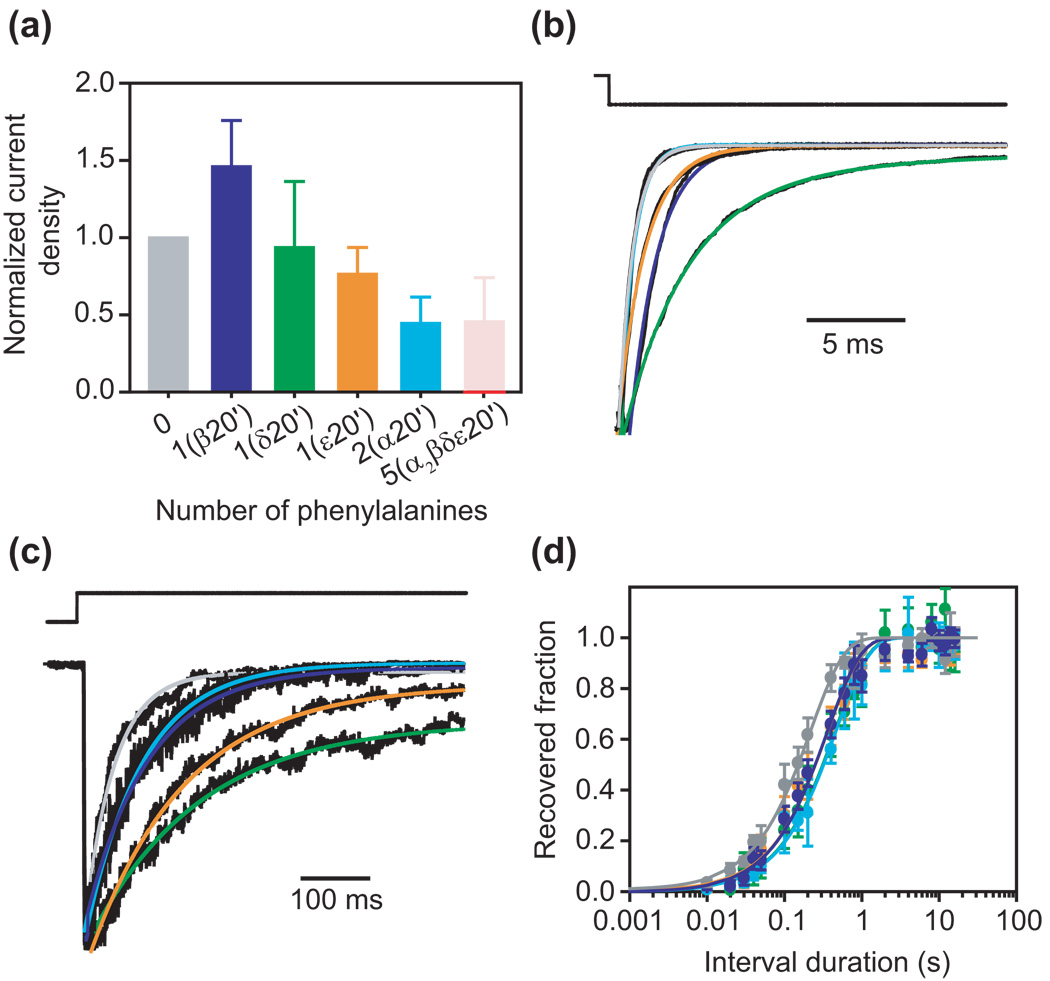

Figure 3. Effect of phenylalanine substitutions at position 20′.

(a) Normalized current densities calculated as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2. In this case, the normalization was done with respect to the wild-type AChR, which has no phenylalanines at position 20′. The bright-red bar indicates the (experimentally determined) current density corresponding to the mutant with a full ring of phenylalanines at position 20′; this value turned out to be zero. The light-red bar in its background indicates the (calculated) current density that would be expected if the five phenylalanines contributed independently to this mutant’s phenotype. (b) Kinetics of deactivation. Each plotted trace is the average response of an outside-out patch to 25 brief pulses of nearly saturating ACh (100 µM) applied as a low-frequency train. The color code is the same as in (a). As indicated in (a), no currents could be recorded from the full phenylalanine-ring mutant. (c) Kinetics of entry into desensitization. Each plotted trace is the response of an outside-out patch to a long pulse of 100-µM ACh; only the first ~550 ms are shown. The color code is the same as in (a). (d) Kinetics of recovery from desensitization estimated using pairs of pulses of 100-µM ACh. Error bars are standard errors calculated from the results of several independent experiments (one experiment per patch). The color code is the same as in (a). All estimated time constants are given in Table 1.

To account for some ambiguities in the alignment of primary sequences (see above), we also expressed AChRs bearing single or multiple phenylalanines at the 20′ pore-facing position of M2 and analyzed the effect of these mutations on channel function and plasma-membrane expression. No macroscopic currents at all could be recorded from the mutant having a full ring of phenylalanines at this position, and only occasional single-channel openings, not enough to generate current–voltage plots or to estimate peak open probabilities but sufficient to conclude that the single-channel conductance is not zero, were observed. Also, we found the expression of this mutant on the plasma membrane to be reduced by a factor of only ~5 (Table 1). Because we could not estimate the peak open probability of the mutant with five phenylalanines, we expressed AChRs with four phenylalanines (in the β1, ε, and the two α1 subunits), instead. Although the macroscopic responses were also very small for this mutant, clusters of single-channel openings could be recorded, and the inferred peak open probability (see Materials and Methods) turned out to be 0.87 ± 0.01 (data from 3 patches), nearly the same value as the wild type’s. Thus, assuming that a fifth phenylalanine in the ring is unlikely to reduce the peak open probability to zero, we suggest that the presence of a full ring of phenylalanines at 20′ also favors the formation of a highly stable refractory state that results from the interaction among the individual phenylalanines (Fig. 3). It is worth noting here that, because of its nearly invariable stoichiometry and the fact that three of its four types of subunit exist as single copies in the pentamer, the muscle AChR is perhaps the most appropriate member of the superfamily to explore the impact of subunit-subunit interactions on channel structure and function.

Stabilizing, non-covalent interactions among properly oriented aromatic side chains in proteins (as well as between nucleic-acid bases16) are well characterized17–20 and are, in fact, a most prominent feature of the crystal structure of ELIC5. We suggest that the highly stable refractory state described here for the full phenylalanine-ring mutant AChRs is entered when the M2 α-helices tilt toward the long axis of the pore enough for the phenylalanine side chains to interact, and thus, “latch” onto one another (Fig. 1c and d). This notion also leads us to suggest that the interactions among these five aromatic side chains stabilize the pore-occluded conformation much more than do interactions among the four aliphatic and one aromatic side chains of the native amino acids at position 16′ or the side chains of the native glutamine and ionizable residues at 20′. It seems reasonable, then, to propose that it is in this stable, non-conductive conformation (rather than in the closed, readily activatable state) that the ELIC channel was crystallized.

A kinetic mechanism for reaching the refractory state

A number of kinetic mechanisms could account for the reduced macroscopic response of the 16′-ring phenylalanine mutant to a step application of nearly-saturating ACh. For example, the refractory conformation (in which the channels are predicted to accumulate) could be entered from the fully-liganded closed state in such a way that, upon ligand binding, the channel could either open or enter this long-lived non-conductive state. Alternatively, the refractory state could be entered even in the absence of ligand in such a way that only a fraction of the (unliganded) channels remains activatable. For the former mechanism to underlie the observed reduced peak responses, the rate of entry into the refractory state (from the fully-liganded closed state) should be much faster than the opening rate. In turn, this feature of the model predicts that openings from individual channels recorded in the presence of high concentrations of ACh would occur mostly as single openings preceded and followed by long sojourns in the refractory state. Because single-channel openings recorded from the 16′-ring phenylalanine mutant in the presence of nearly-saturating ACh occur, instead, as groups (“clusters”) of several openings in a row separated by comparatively brief shuttings (attributable to brief visits to the closed conformation), we dismiss this mechanism and propose that the refractory state is attained mostly in the absence of ligand. Of course, our results do not rule out the possibility that the refractory conformation can also be entered from liganded closed or open states, but these transitions could not account for the much-reduced peak-current response of the phenylalanine mutant to the application of ACh.

A context-dependent effect

The observation that, in the phenylalanine-ring AChR mutants, a large fraction of the channels are unresponsive to the application of activating ligand made us wonder what the physiological role of channels that naturally contain such rings of aromatic residues (Supplementary Fig. 1) might be. However, it is important to bear in mind that channels naturally having full rings of aromatic side chains at pore-facing positions display very low sequence identity with the muscle AChR, and hence, that other amino-acid differences may well tilt the free-energy landscape in such a way as to destabilize the unresponsive, refractory conformation relative to all others. An inspection of primary sequences revealed that some of the channels with an aromatic residue at the position that aligns with residue 246 of ELIC also have an aromatic residue at the adjacent position, being a tyrosine (tyrosine 247) in the particular case of ELIC (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, we engineered a tyrosine at position 17′ of each muscle-AChR subunit, next to the 16′ phenylalanine, and analyzed the effect of this double ring of aromatic side chains on function. Remarkably, we found that this mutant displays a very high open probability even in the absence of ligand (Fig. 4), an effect that is quite the opposite of that caused by the 16′ phenylalanine-ring mutations alone (Fig. 2a). Evidently, all side chains contribute to shape the conformational dynamics of a protein, and channels with native rings of pore-facing aromatic residues, such as ELIC, need not be defunct.

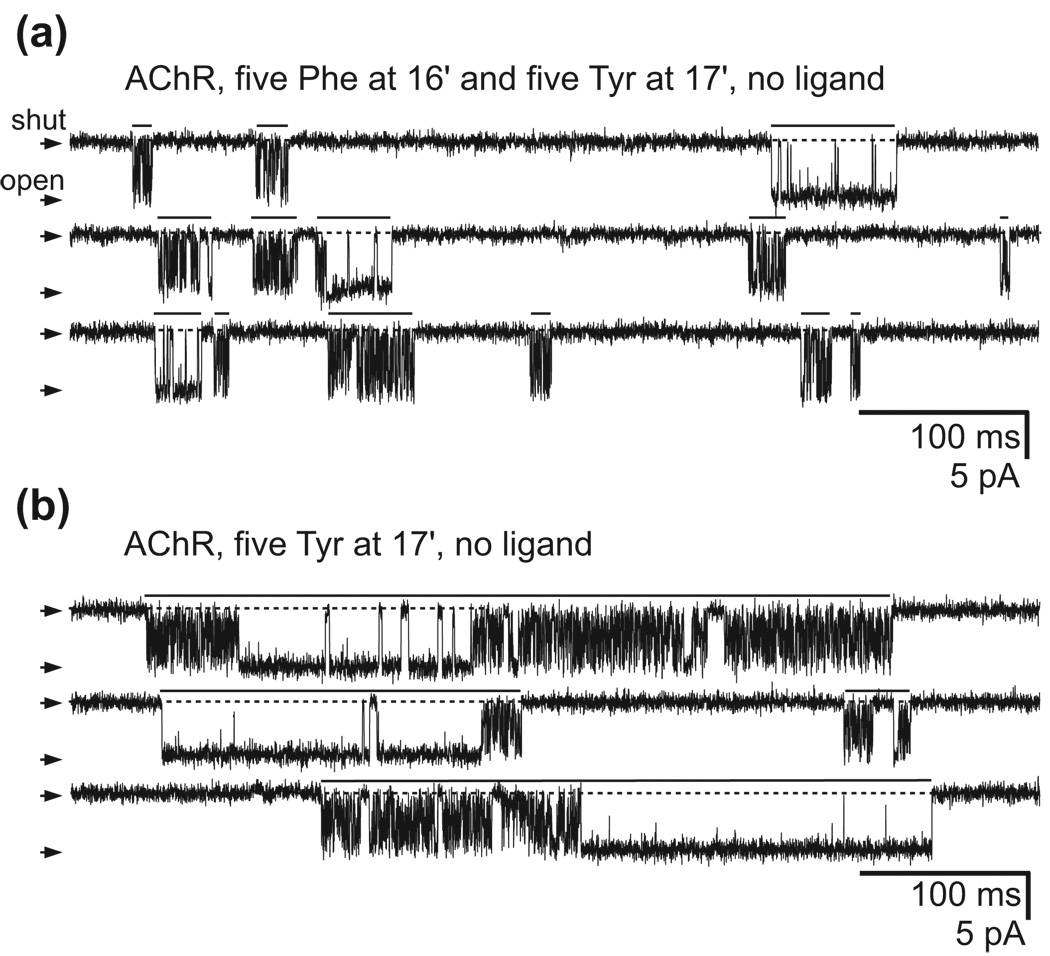

Figure 4. The importance of the surroundings.

The effect of engineering a full ring of pore-facing aromatic side chains at position 16′ of the muscle AChR depends on the rest of the sequence. (a) When engineered on the background of a mutant AChR already containing a ring of aromatic side chains (here, of tyrosines) at an adjacent position (position 17′), the effect of introducing a full ring of phenylalanines at position 16′ is offset as evidenced by the high open probability of the resulting receptor even in the absence of ligand. For all current traces, V ≅ −100 mV, openings are downward deflections, and display fc ≅ 5 kHz. (b) When engineered on the wild-type AChR’s background, a ring of tyrosines at position 17′ increases the gating equilibrium constant of the unliganded receptor to the extent that openings occur as well-defined clusters of long duration and high open probability separated by what appear to be desensitized intervals. The additional presence of a ring of phenylalanines at position 16′ (shown in (a)) shortens these clusters of unliganded openings (while leaving the intracluster open probability largely unaffected) consistent with the “refractory state-favoring” effect of these side chains in the absence of ligand. In the representative recordings shown here, clusters are shortened by a factor of ~50, from ~850 ms (n = 309 clusters) to ~18 ms (n = 9,664 clusters). Some representative clusters are identified on the traces by unbroken horizontal lines. Notice the complexity of unliganded gating in these two mutant AChRs, with periods of long (apparent) openings alternating with stretches of very brief openings (“flickers”).

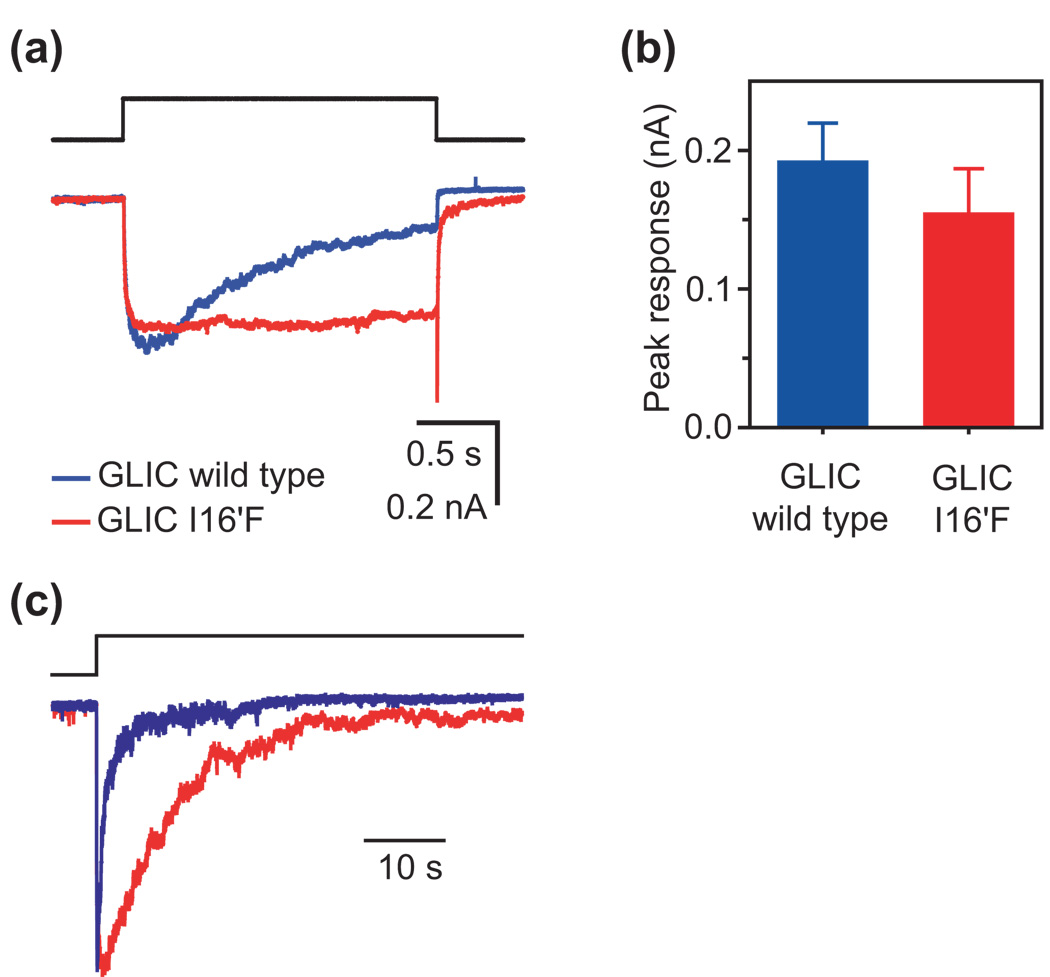

The importance of the rest of a protein’s amino-acid sequence on the effect of mutations is also readily evident in the case of the proton-activated GLIC channel. In this case, engineering a full ring of phenylalanines at the position aligned with ELIC’s phenylalanine 246 does not affect the peak response of the channel to proton-concentration jumps (from pH 7.4 to pH 4.5; Fig. 5a and b). Thus, whereas introducing a full ring of pore-facing phenylalanines in the wild-type AChR favors a refractory conformation that very likely resembles the conformation caught in the crystal structure of ELIC (at least at the level of the transmembrane pore), these mutations fail to do so when engineered in the context of the sequence of GLIC.

Figure 5. Effect of phenylalanine substitutions in the GLIC channel.

(a) and (b) In marked contrast to its effect on the wild-type muscle AChR, introducing a ring of phenylalanines at position 16′ of the GLIC channel does not affect much the peak response to jumps in pH from 7.4 to 4.5. The number of individual responses analyzed (one response per patch) was 21 for the wild-type GLIC and 8 for the I16′F GLIC mutant. (c) Kinetics of entry into desensitization. Each plotted trace is the response of an outside-out patch to a long pH jump from 7.4 to 4.5. The time course of entry into desensitization of the wild-type GLIC displayed high patch-to-patch variability, the time constant ranging from 75 ms to 9.9 s in 23 patches (mean ± standard error = 1.4 ± 0.5 s). The I16′F mutant also desensitizes completely, but with kinetics that are slower than the wild-type’s by a factor of ~7.5. The color code is the same for all three panels.

Incidentally, but of high relevance to the broader implications of this paper, we notice that the wild-type GLIC channel desensitizes completely within a few seconds upon exposure of its extracellular side to pH 4.5 (desensitization time constant 2245; 1.4 ± 0.5 s, 23 patches; Fig. 5c) hinting at the possibility that the crystal structures obtained at pH 4.0 (Ref. 7) and 4.6 (Ref. 6) do not correspond to the open, but rather, to the (well-known) desensitized state. This may well be yet another example of the frequent (and, sometimes, difficult-to-bridge) disconnect between protein structural models and the functional states they represent. As elaborated in the following section, the desensitization time courses of wild-type and mutant GLIC in Fig. 5c proved also instrumental in narrowing the gap between the phenylalanine-ring-dependent refractory state, the desensitized state and the structural model of ELIC.

A distinct refractory conformation

All wild-type members of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily can desensitize, that is, enter a non-conductive conformation that, when fully bound to neurotransmitter, becomes the most stable state of the channel21–23. Hence, we wondered whether the refractory conformation described above for the muscle AChR might represent the well-known desensitized state, and thus, whether the effect of the full ring of phenylalanines is, rather trivially, to stabilize this conformation to such an extent that it becomes the most stable state of the channel also when unliganded.

We reasoned that if entry into desensitization involved the inward tilting of the M2 helices and the ensuing interaction among the 16′ side chains (as seen in the crystal structure of ELIC; Fig. 1d), then the introduction of a full ring of pore-facing phenylalanines at this position could only increase the stability of the desensitized state. In turn, for a channel with a large desensitization equilibrium constant (that is, a channel that desensitizes nearly completely upon exposure to ligand), this stabilization would be expected to speed up the macroscopic time course of entry into desensitization to a greater or lesser degree, but not to slow it down appreciably.

The time constant of entry into desensitization of the muscle AChR changes little upon engineering a full ring of phenylalanines at position 16′ (Fig. 2c and Table 1). However, the notion that this mutant could also enter the refractory conformation when exposed to high concentrations of ACh obscures the quantitative interpretation of the “desensitization” timecourse. Hence, we figured that this issue would be resolved most unambiguously if data were obtained from a mutant channel that, while able to desensitize, shows no signs of being able to enter the refractory state characterized above. Furthermore, it would be desirable to perform these experiments on a channel with a sufficiently low unliganded-gating equilibrium constant so as to maximize the current signal upon ligand application.

It turns out that the GLIC channel meets all of these conditions: the 16′ phenylalanine mutant (I16′F) desensitizes and displays wild-type like peak currents in response to pH jumps from 7.4 to 4.5 (Fig. 5a and b), and has a negligible open probability at pH 7.4. As clearly shown in Fig. 5c, this mutant enters the desensitized state more slowly (desensitization time constant ≅ 10.5 ± 2.8 s, 4 patches) than does the wild-type GLIC, a finding that suggests that entry-into-desensitization is unlikely to involve a conformational change that brings the 16′ (or 20′) side chains together. In other words, the crystal structure of ELIC is unlikely to correspond to the well-known desensitized state of the members of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily.

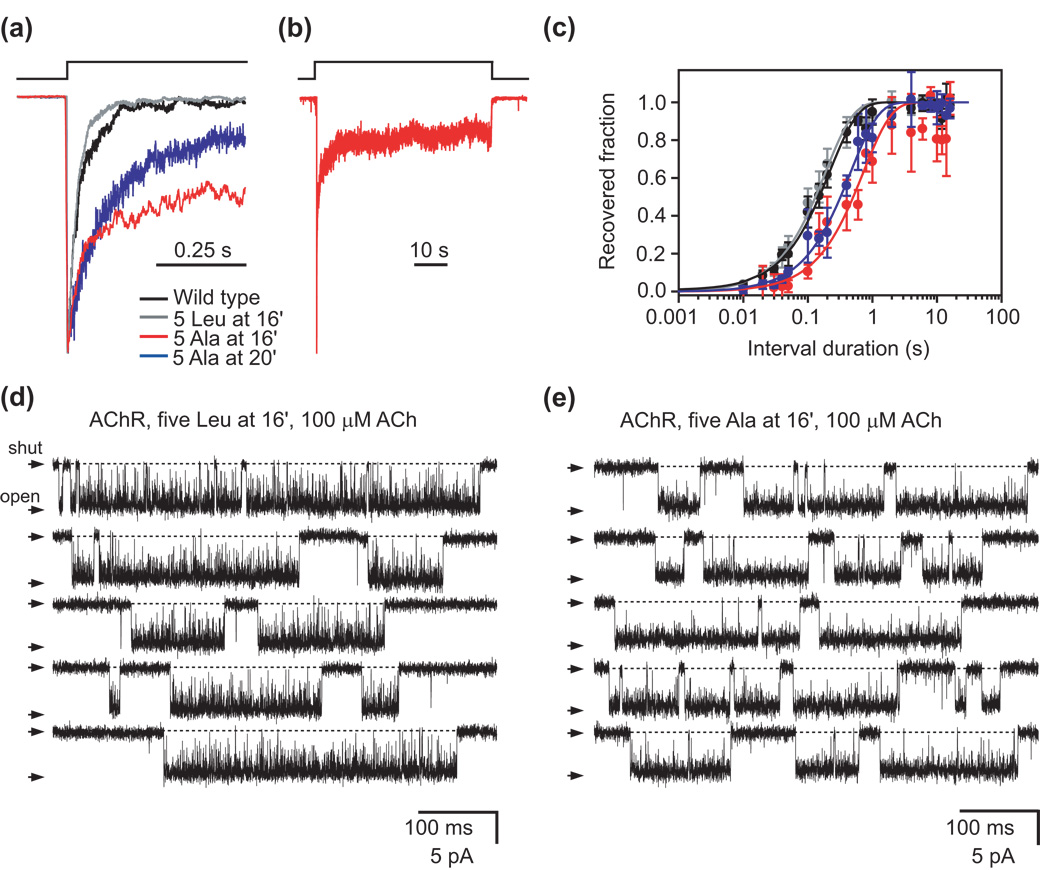

To complement this argument, we also wondered what the effect of shortening the side chains occupying position 16′ on desensitization is. As shown in Fig. 6, the current through a mutant AChR containing a full ring of alanines at 16′ (instead of four leucines and one phenylalanine; Supplementary Fig. 1) declines after reaching a peak, much like in the case of the wild-type channel or the mutant with five leucines at this position. To elucidate whether the non-zero current observed for the alanine mutant by the end of the ACh pulses (Fig. 6b) represents the current flowing through desensitized channels that were rendered “leaky” by the side chain-shortening mutations or, rather, the current through the fraction of AChRs that recover from desensitization in the presence of ACh, we recorded single-channel currents in the presence of a nearly saturating (and thus, desensitizing) concentration of ACh. As shown in Fig. 6d and e, current transitions clearly proceed between the zero-current baseline and the open-channel level, indicating that this mutant gate(s) shut tightly. We also mutated the five side chains forming the 20′ ring of the AChR to alanine, and the results were essentially the same (Fig. 6a). From these results, we conclude that the wild-type ring of 16′ (or 20′) side chains is unlikely to act as the desensitization gate itself.

Figure 6. Full alanine-ring AChR mutants desensitize, too.

(a) Although more slowly than the wild-type receptor or the mutant having a full ring of leucines at position 16′, the mutant AChR containing a full ring of alanines at this position desensitizes, too; the same is the case for the mutant having a full ring of alanines at position 20′. Each plotted trace is the response of an outside-out patch to a long pulse of 100-µM ACh; only the first ~550 ms are shown. (b) Full time course of entry into desensitization of the 16′ alanine mutant in response to a 1-min application of 100-µM ACh. (c) Kinetics of recovery from desensitization estimated using pairs of pulses of 100-µM ACh. Error bars are standard errors calculated from the results of several independent experiments (one experiment per patch). The color code is the same as in (a). (d) and (e) Single-channel inward currents recorded from the indicated mutants at ~−100 mV and in the presence of 100-µM ACh. Irrespective of whether position 16′ is occupied by leucines or (the shorter) alanines, periods of closed-open activity are interrupted by sojourns in the (tightly shut) desensitized state. For all current traces, openings are downward deflections, and display fc ≅ 5 kHz.

It seems clear, then, that the refractory state and the desensitized state are distinct conformations of the members of the nicotinic-receptor superfamily. Perhaps consistent with this notion, the pore-lining α-helices of GLIC in the crystals grown at pH 4.0 or 4.6 tilt outwardly at the level of position 16′ (Refs 6 and 7; Supplementary Fig. 4) rather than inwardly (as is the case for ELIC5 (Fig. 1d)). We termed the refractory conformation characterized here the “π-type desensitized state” to distinguish it from the “regular” desensitized conformation while emphasizing the requirement of aromatic side chains at pore-facing positions for its formation.

Phenylalanine substitutions at other positions

To test whether the described effect of full phenylalanine rings on the conformational dynamics of the AChR is an exclusive property of the 16′ and 20′ positions or, rather, a more general phenomenon associated with the pore-facing stripe of M2, we extended this mutational analysis to positions 6′, 9′ and 13′.

At 13′, a full ring of phenylalanines reduced the current density by a factor <2 relative to the wild-type AChR (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1), which we consider negligible, especially in light of the much larger effect of the phenylalanine-ring mutations at position 16′ or 20′ (Figs. 2a and 3a, and Table 1). At positions 6′ and 9′, full rings of phenylalanines reduced the peak-current amplitudes to zero, but because the amplitude of the single-channel currents (at −80 mV) were also reduced to immeasurably low values, the corresponding current densities could not be calculated with any certainty. On the other hand, mutants containing only three phenylalanines at position 6′, or two at position 9′, displayed non-zero peak-current amplitudes, and both the single-channel currents and the intracluster open probabilities could be measured; the corresponding current densities turned out to be similar to the wild-type value (lower by a factor of <2; Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Perhaps, then, a full ring of phenylalanines is needed at position 6′ or 9′ of the muscle AChR to create a stable π-type desensitized conformation.

Intriguingly, a naturally-occurring serine-to-phenylalanine mutation at position 6′ of the neuronal α4 AChR subunit (which contributes two or three copies to heteromeric AChRs that are highly expressed in the brain) causes a rare form of epilepsy24. Whether two or three phenylalanines at position 6′ of α4-containing AChRs succeed in creating a refractory state, and whether this non-responsive conformation underlies the disease, remains to be explored.

Concluding remarks

It is becoming increasingly clear that assigning a functional state (that is, closed, open, desensitized, inactivated) to the structural model of an ion channel solely on the basis of how the transmembrane pore looks like (say, occluded or not occluded) may be misleading.

In the case of GLIC, we noticed that the channel desensitizes completely in a matter of seconds upon exposure of its extracellular side to pH 4.5. Of course, however, our results do not rule out the possibility that the X-ray crystal structures obtained at pH 4.0 (Ref. 7) and 4.6 (Ref. 6) still represent the open-channel conformation, as originally proposed. But if the conformational dynamics of the channel under the crystallization conditions did not differ from those in the cell membrane in hopelessly complicated ways, then the possibility that GLIC crystallized in the desensitized conformation would seem more likely. Alternatively, these results may point to a crucial role of the cell membrane as a modulator of the energetics of conformational changes in this channel and, perhaps, all other members of the superfamily.

The functional state of ELIC in the crystal5 is even more difficult to identify, if only because the activating ligand is not known. Nevertheless, the parallel between the edge-to-face interaction among phenylalanines 246 in the structural model of ELIC (PDB code 2VL0) and the functional interaction among the phenylalanines engineered at the aligned position of the muscle AChR suggest that ELIC may, indeed, have been crystallized in the π-type desensitized state. By no means, however, do our results imply that this conformation cannot represent a true closed, resting state of the ELIC channel itself. Rather, we suggest that this conformation is unlikely to represent the closed-channel state of the muscle AChR and, by extension, of the other nicotinic-type receptors from animals (note that all metazoan members of the superfamily, and perhaps also GLIC, behave in a qualitatively very similar manner). Also, we do not mean to imply here that the particular tilt angle of the M2 α-helices of ELIC (Fig. 1d) is maintained solely by the aromatic–aromatic interactions among the side chains of the phenylalanines 246. Certainly, other amino-acid differences may also have evolved concomitantly to stabilize the pore-occluding conformation of these pore-lining helices. In turn, this notion leads us to suggest that mutation of the phenylalanines 246 to non-aromatic residues need not be expected to change the tilt of the M2 α-helices of ELIC drastically.

Many questions remain as to the functional properties of this novel refractory conformation. For example, although our data show that the π-type desensitized state is the most stable conformation of some phenylalanine-ring mutant muscle AChRs (at position 16′ or 20′) in the absence of ligand, we still know very little about the interconversion between this state and the closed, open and regular desensitized states in ligand-bound AChRs. Also, we do not know the extent to which this novel conformation is populated in channels that contain naturally-occurring full rings of aromatic residues at pore-facing positions other than the notion that ELIC seems to have been crystallized in this state. What is clear, however, is that the π-type desensitized conformation constitutes a compelling example of how relatively small details of the primary sequence can sculpt the free-energy landscape of a protein not only by altering the properties of existing peaks and valleys, but also, by creating new ones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA clones, mutagenesis and heterologous expression

HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type or mutant complementary DNAs (cDNAs) encoding for the mouse-muscle AChR (α1, β1, δ and ε subunits) or the bacterial GLIC channel4,14 using a calcium-phosphate precipitation method. AChR cDNAs in the expression vector pRBG4 were provided by Dr. Steven Sine. GLIC cDNA was prepared by inserting a commercially synthesized stretch of DNA (Integrated DNA Technologies) consisting of the signal peptide of the chicken α7 AChR followed by the sequence of the mature GLIC into the pcDNA3.1 vector, essentially as described by Corringer and coworkers14. Mutations were engineered using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing.

Electrophysiological recordings and analysis

Ensemble (“macroscopic”) currents were recorded from transfected HEK-293 cells using the outside-out configuration of the patch-clamp technique, whereas single-channel currents were recorded using the cell-attached configuration. For outside-out recordings, the ligand was applied to the external aspect of outside-out patches as rapid jumps (solution-exchange time10–90%<150 µs). These step changes in the concentration of ligand were achieved by the rapid switching of two solutions (differing only in the presence or absence of ligand) flowing from either barrel of a piece of theta-type capillary glass mounted on a piezo-electric device25,26 (Burleigh-LSS-3100; Exfo). For all outside-out recordings, the patch-pipette solution consisted of (in mM) 110 KF, 40 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA and 10 Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, whereas the agonist-free solution flowing through one of the barrels of the theta-type tubing consisted of (in mM) 142 KCl, 5.4 NaCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4. In the case of recordings from the AChR, the solution flowing through the second barrel of the theta-type tubing was the same as that in the first barrel with the addition of 100 µM ACh, a nearly saturating concentration. Indeed, upon the step application of this concentration of ACh, the open probability of the wild-type muscle AChR reaches a peak value that is ~90% of the maximal attainable open probability. In the case of recordings from GLIC, the second-barrel solution was the same as that in the first barrel with the exception that the pH was adjusted to a value of 4.5 and was buffered with 10-mM acetic-acid/acetate instead of Hepes. For cell-attached recordings, the solution bathing the cells consisted of (in mM) 142 KCl, 5.4 NaCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4; the pipette solution was the same as that in the bath with or without the addition of ligand ([ACh] = 100 µM; [choline] = 20 mM). The temperature was 22°C for all current recordings. The effective bandwidth before data analysis was DC–5 kHz for macroscopic currents and DC–20 kHz for single-channel currents. Macroscopic-current recordings were analyzed using pClamp 9.0 (MDS Analytical Technologies) and SigmaPlot 7.101 (SPSS Inc.). Single-channel currents were analyzed using the SKM-MIL combination in QuB software27,28, MAPLE 6 (Waterloo Maple, Inc.) and in-house developed programs.

The maximum value of the macroscopic current elicited in response to a step application of ligand (“the peak amplitude”) was estimated by exposing outside-out patches to 2-s pulses of agonist, at −80 mV, both for the AChR and GLIC. In these experiments, only a single pulse of agonist was applied to each patch of membrane to ensure that the population of channels was exposed to agonist only once. The deactivation kinetics of the AChR were estimated by exposing outside-out patches to trains of 1-ms pulses of 100-µM ACh (25 pulses per train delivered at 1 Hz), at −80 mV. The responses to the individual pulses within a train were aligned and averaged, and the decaying phase was fitted (least-squares method) from the peak of the current until the end of the transient with exponential functions (Figs. 2b and 3b). The kinetics of entry into desensitization of the AChR were estimated by exposing outside-out patches to pulses of 100-µM ACh (Figs. 2c and 3c), whereas those of GLIC were estimated by applying pH jumps from 7.4 to 4.5 (Fig. 5a and c), at −80 mV. The decaying phase of these current transients were fitted (least-square method) from the peak of the currents until the end of the agonist application with mono-exponential functions. The kinetics of recovery from desensitization of the AChR were estimated using pairs of conditioning and test pulses (1-s and 100-ms in duration, respectively) of 100-µM ACh, separated by ACh-free intervals of variable length, at −80 mV. The interval between any two consecutive pairs of pulses was ≥10 s to ensure complete recovery from desensitization before application of each new conditioning pulse. The fraction of recovered AChRs was calculated as the peak response to the test pulse minus the current at the end of the corresponding conditioning pulse divided by the difference between the peak response to the conditioning pulse and the current at the end of it. Plots of recovered fraction of receptors as a function of the duration of the interval between the conditioning and test pulses were well fitted with mono-exponential-rise functions (Fig. 2d, 3d, and 6c) despite the multiple steps that must be involved in the recovery of ACh-diliganded desensitized receptors following ACh removal (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Clusters of single-channel openings from the wild-type and mutant AChRs were defined as series of openings separated by shuttings (that is, sojourns in a non-conductive conformation) shorter than a critical time, tcrit. All shuttings shorter than tcrit were interpreted as sojourns in closed states, whereas all shuttings longer than tcrit were interpreted as sojourns in desensitized states. However, owing to the exponential nature of dwell-time distributions, no tcrit value can perfectly separate sojourns belonging to different exponential components, and therefore, some misclassification is inevitable. We chose to control this error by using a tcrit equal to the time value that minimizes the total number of misclassified shuttings (a separate value for each recording), essentially as proposed by Jackson and coworkers29 with only minor modifications30. The open probability within these clusters, which were elicited by the constant presence of 100-µM ACh in the pipette of cell-attached patches, was measured and taken as an approximation to the probability of the channel being open (rather than closed) between consecutive sojourns in desensitized states. In turn, this (equilibrium) probability was taken as an approximation to the peak open probability of the wild-type and mutant channels during the macroscopic-current transients that follow the step application of a nearly saturating concentration of ACh (100 µM). Indeed, calculations show that wild-type-like kinetics of entry into desensitization (see the curve with k+D = 30 s−1, for example, in Supplementary Fig. 3) are not fast enough to reduce the peak open probability appreciably from the value this parameter would reach if desensitization did not occur at all (k+D = 0). Hence, because the open probability within clusters is expected to be minimally contaminated with sojourns in the desensitized conformation, we conclude that this equilibrium, single-channel parameter is a valid approximation to the maximum open probability attained on exposure to an ACh-concentration jump. The duration of each cluster was measured from the beginning of the first opening to the end of the last one, including all the shuttings in between.

Plasma-membrane AChR expression

To estimate the number of wild-type or mutant AChRs on the plasma membrane, transfected cells were incubated with 20-nM [125I]-α-bungarotoxin (PerkinElmer) in fresh DMEM culture medium at 4 °C for 2–3 h so as to saturate all toxin-binding sites. The associated radioactivity was measured in a γ-counter and was normalized to the corresponding mass of total protein, which was quantified using the bicinchoninic-acid method (Thermo Scientific) after solubilizing the cells with 0.1 N NaOH. The non-specific binding of radiolabeled toxin was estimated on cells transfected with cDNAs encoding for the β1, δ and ε subunits of the mouse-muscle AChR (but not the α1 subunit). The amount of [125I]-α-bungarotoxin bound to these mock-transfected cells (normalized to total protein content) was never higher than 6% of that associated with the expression of the wild-type channel.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank S. Sine for wild-type muscle AChR subunit cDNA; S. Elenes and D. Papke for critical advice on fast-perfusion experiments; S. Rempe, S. Varma and E. Tajkhorshid for discussions; and G. Papke, M. Maybaum and J. Pizarek for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01–NS042169 and corresponding ARRA Supplement to C.G.).

Abbreviation used

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tate CG. Comparison of three structures of the multidrug transporter EmrE. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hite RK, Raunser S, Walz T. Revival of electron crystallography. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuello LG, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Sompornpisut A, Purdy MD, Wiener MC, Perozo E. Design and characterization of a constitutively open KcsA. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasneem A, Iyer LM, Jakobsson E, Aravind L. Identification of the prokaryotic ligand-gated ion channels and their implications for the mechanisms and origins of animal Cys-loop ion channels. Genome Biology. 2004;6:R4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2008;452:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature06717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bocquet N, Nury H, Baaden M, Le Poupon C, Changeux JP, Delarue M, Corringer PJ. X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009;457:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature07462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilf RJ, Dutzler R. Structure of a potentially open state of a proton-activated pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2009;457:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature07461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:967–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckstein O, Kai T, Sansom MSP. Not ions alone: barriers to ion permeation in nanopores and channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14694–14695. doi: 10.1021/ja045271e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peter C, Hummer G. Ion transport through membrane-spanning nanopores studied by molecular dynamics simulations and continuum electrostatics calculations. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2222–2234. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckstein O, Sansom MSP. A hydrophobic gate in an ion channel: the closed state of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Phys. Biol. 2006;3:147–159. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/3/2/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rempe SB, Pratt LR. The hydration number of Na+ in liquid water. Fluid Phase Equilibria. 2001;183:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorgensen WL, Severance DL. Aromatic–aromatic interactions: free-energy profiles for the benzene dimer in water, chloroform, and liquid benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4768–4774. (1990) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bocquet N, Prado de Carvalho L, Cartaud J, Neyton J, Le Poupon C, Taly A, Grutter T, Changeux JP, Corringer PJ. A prokaryotic proton-gated ion channel from the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor family. Nature. 2007;445:116–119. doi: 10.1038/nature05371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imoto K, Busch C, Sakmann B, Mishina M, Konno T, Nakai J, Bujo H, Mori Y, Fukuda K, Numa S. Rings of negatively charged amino acids determine the acetylcholine receptor channel conductance. Nature. 1988;335:645–648. doi: 10.1038/335645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sponer J, Riley KE, Hobza P. Nature and magnitude of aromatic stacking of nucleic acid bases. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008;10:2595–2610. doi: 10.1039/b719370j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burley SK, Petsko GA. Aromatic-aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science. 1985;229:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.3892686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter CA, Singh J, Thornton JM. π–π interactions: the geometry and energetics of phenylalanine–henylalanine interactions in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;218:837–846. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serrano L, Bycroft M, Fersht AR. Aromatic-aromatic interactions and protein stability. Investigation by double-mutant cycles. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;218:465–475. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90725-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGaughey GB, Gagné M, Rappé AK. π-stacking interactions. Alive and well in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15458–15463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz B, Thesleff S. A study of the desensitization produced by acetylcholine at the motor end-plate. J. Physiol. 1957;138:63–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dilger JP, Liu Y. Desensitization of acetylcholine receptors in BC3H-1 cells. Pflugers Arch. 1992;420:479–485. doi: 10.1007/BF00374622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franke C, Parnas H, Hovav G, Dudel J. A molecular scheme for the reaction between acetylcholine and nicotinic channels. Biophys. J. 1993;64:339–356. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81374-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinlein OK, Mulley JC, Propping P, Wallace RH, Phillips HA, Sutherland GR, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. A missense mutation in the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α4 subunit is associated with autosomal dominant nocturnal front lobe epilepsy. Nature Genetics. 1995;11:201–203. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elenes S, Ni Y, Cymes GD, Grosman C. Desensitization contributes to the synaptic response of gain-of-function mutants of the muscle nicotinic receptor. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;128:615–627. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elenes S, Decker M, Cymes GD, Grosman C. Decremental response to high-frequency trains of acetylcholine but unaltered fractional Ca2+ currents in a panel of “slow-channel syndrome” nicotinic receptor mutants. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009;133:151–169. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin F, Auerbach A, Sachs F. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophys. J. 1996;70:264–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin F. Restoration of single-channel currents using the segmental k-means method based on Hidden Markov modeling. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1488–1501. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson MB, Wong BS, Morris CE, Lecar H, Christian CN. Successive openings of the same acetylcholine receptor channel are correlated in open time. Biophys. J. 1983;42:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purohit Y, Grosman C. Estimating binding affinities of the nicotinic receptor for low-efficacy ligands using mixtures of agonists and two-dimensional concentration-response relationships. J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;127:719–735. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Sansom MS. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.