SYNOPSIS

Distance learning is an effective strategy to address the many barriers to continuing education faced by the public health workforce. With the proliferation of online learning programs focused on public health, there is a need to develop and adopt a common set of principles and practices for distance learning. In this article, we discuss the 10 principles that guide the development, design, and delivery of the various training modules and courses offered by the North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness (NCCPHP). These principles are the result of 10 years of experience in Internet-based public health preparedness educational programming. In this article, we focus on three representative components of NCCPHP's overall training and education program to illustrate how the principles are implemented and help others in the field plan and develop similar programs.

Distance learning is an effective strategy to address the many barriers to continuing education faced by the public health workforce, including budget constraints, overloaded schedules, the need for on-the-job learning opportunities, lack of access (particularly in rural areas), and difficulty in finding training opportunities on core public health concepts.1 By allowing public health practitioners to “expand their skills within their current positions, organizations, and communities,”2 distance learning also provides an opportunity for just-in-time training during emergencies.

In its 2003 publication, Who Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century, the Institute of Medicine noted the recent increase in distance-learning opportunities for the public health workforce, including master's and doctoral degree programs and continuing education training modules and courses.3 With the proliferation of distance-learning programs focused on the public health workforce, the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice (Council on Linkages) is advocating for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to “adopt a common set of principles and practices for distance learning [to] ensure that distance learning development and delivery is of high quality and remains learner centered.”4

In this article, we discuss 10 principles that guide the development, design, and delivery of the various training modules and courses that comprise 10 years of experience in Internet-based public health preparedness (PHP) educational programming by the North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness (NCCPHP). These guiding principles are as follows:

Link educational offerings to established professional competencies.

Base educational offerings on assessed needs of the target audience.

Design educational offerings based on appropriate cognitive learning levels.

Utilize reusable learning objects.

Know the target audience (or partner with someone who does).

Develop well-organized courses and programs with a standard look and feel.

Provide readily accessible technical support to participants and students.

Manage student and instructor expectations.

Provide continuous feedback to participants and students.

Continually evaluate, refine, and update course content and delivery.

EDUCATIONAL OPTIONS

NCCPHP is a program of the North Carolina Institute for Public Health (NCIPH), the service and outreach arm of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Gillings School of Global Public Health. NCCPHP is part of a national network of Centers for Public Health Preparedness funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The overall mission of NCCPHP is to improve the capacity of public health agencies and their staffs to prepare for and respond to emerging public health threats through research, educational programs, and technical assistance. As part of its effort to achieve this mission, NCCPHP has developed multiple Internet-based educational options to meet the assessed needs1,5–9 of the public health workforce.

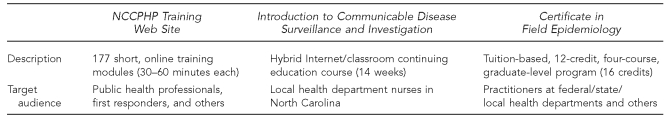

NCCPHP's educational options are designed to address diverse audience needs through a variety of Internet-based training modules, continuing education courses, and an academic graduate certificate. In this article, we focus on NCCPHP's 10 guiding principles, using three representative components (Figure 1) of the overall training and education program to illustrate how the principles are implemented: (1) the NCCPHP Training Web Site (TWS), (2) a 14-week continuing education hybrid Internet/classroom course entitled Introduction to Communicable Disease Surveillance and Investigation (hereafter, Communicable Disease), and (3) the Certificate in Field Epidemiology.

Figure 1.

Components of NCCPHP's overall PHP training and education program selected to illustrate how the 10 guiding principles for Internet-based PHP educational programming are implemented

NCCPHP = North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness

PHP = public health preparedness

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

The 10 principles that guide the development, design, and delivery of NCCPHP's comprehensive Internet-based PHP training and education program are focused on maximizing the quality of individual training modules and courses, which have consistently received positive evaluations from students and participants.10–12

1. Link educational offerings to established professional competencies

To ensure NCCPHP training modules and courses meet the needs of public health professionals, they have been linked to appropriate public health competencies. NCCPHP training programs rely on three sets of competencies: (1) the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals (2001 and 2009 versions), developed by the Public Health Foundation and Council on Linkages (while the Core Competencies have three tiers based on varying levels of experience, only the Tier 2 competencies had been completed and released at the time the competencies were linked to TWS trainings);13,14 (2) the Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies, developed by CDC and the Columbia University School of Nursing—Center for Health Policy;15 and (3) the Applied Epidemiology Competencies (AECs), developed by CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) to improve the practice of epidemiology in public health agencies.16 The AECs also include different tiers for different levels of experience and training: Tier 1, entry-level or basic epidemiologist; Tier 2, mid-level epidemiologist; Tier 3a, senior-level epidemiologist—supervisor and/or manager; and Tier 3b, senior scientist/subject-area expert.

The TWS addresses competencies from all three sets. One or more of the Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness Competencies are addressed by 64 of the 177 training modules on the TWS. In addition, 45 of the 76 Tier 2 Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals are addressed by the TWS. Because the TWS modules focused on epidemiology are awareness-level trainings, they are linked to selected AEC Tier 1 and Tier 2 competencies (72 out of 210 combined Tier 1 and Tier 2 competencies).

TWS users can search for training opportunities by clicking on any of the three competency sets and then selecting a specific competency. For example, clicking on the Bioterrorism Competency “describe the public heath role in emergency response in a range of emergencies that might arise” directs the user to 42 training modules that address this particular competency.

The hybrid Internet/classroom Communicable Disease training course addresses the AECs. In North Carolina local health departments, public health nurses are charged with responding to disease reports received from clinicians, and recognizing, investigating, and reporting disease outbreaks to the state health department. These basic applied epidemiologic functions can be linked to the Tier 1 AECs and serve as the basis for the course. The four courses that comprise the certificate curriculum cover a wide spectrum of epidemiologic competencies and, as such, are linked to the Tier 1 and Tier 2 AECs, as well as to epidemiologic competencies developed by the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice.6

2. Base educational offerings on assessed needs of the target audience

The TWS modules are designed to meet the assessed training needs of the local, state, and national public health workforce. These training needs have been identified by national surveys, such as the Health Resources and Services Administration—Bureau of Health Professions' Public Health Workforce Study,1 and state surveys, such as the North Carolina Public Health Workforce Training Needs Assessment conducted by NCCPHP in 2003–2004.5 In addition, NCCPHP solicits feedback from registered TWS participants regarding topics on additional training opportunities desired. Some of the TWS's most frequently completed modules (such as HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act]: An overview of HIPAA and the Privacy Rule, and Title VI—Cultural Competency) are results of this feedback.

The curriculum for the Communicable Disease course was developed to meet the specific needs of North Carolina public health nurses, as assessed by the North Carolina Public Health Workforce Training Needs Assessment. In this survey, 41% of North Carolina local public health nurses indicated a high need for training in recognizing and responding to a disease outbreak in their communities.7

The certificate program was designed to address the need for applied epidemiology education for working public health professionals, as identified by CSTE. In its 2004 report, “National Assessment of Epidemiologic Capacity: Finding and Recommendations,” CSTE found that only 43% of infectious disease epidemiologists working in state and territorial health departments reported academic training in epidemiology.8 Furthermore, 59% of state and territorial health departments who answered a CSTE survey regarding their applied epidemiology capacity stated they needed additional training to conduct an evaluation of surveillance systems; 53% needed additional training to create an analysis plan and perform data analysis.17

In addition, NCIPH conducted a market research study of individuals who had participated in NCIPH Office of Continuing Education programs to gauge interest in a certificate program. An Internet-based survey asked respondents about their health-related professional experience, whether they had epidemiologic duties in their current positions, if they had formal training in epidemiology, and what courses were of greatest interest to them in a certificate program. Of the 847 respondents who completed the survey, 22% were “very interested” and 35% were “interested” in obtaining a certificate in field epidemiology.

3. Design educational offerings based on appropriate cognitive learning levels

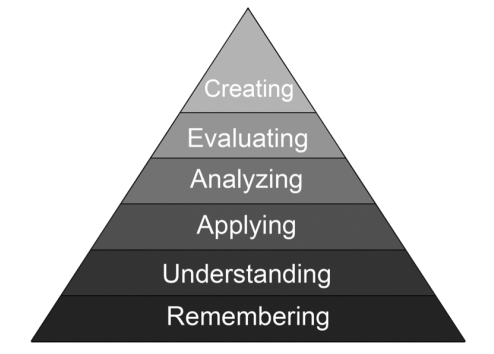

Each training module or course in the NCCPHP training and education program is designed to achieve one of six increasingly complex levels of cognitive domain (Figure 2), as defined by Anderson and Krathwohl's taxonomy for teaching, learning, and assessment,18 a recently revised version of Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive domain,19 originally created in 1956.

Figure 2.

Revised Bloom's taxonomy,a used by the NCCPHP as a guide to determine the appropriate cognitive learning levels for PHP educational offerings

aOverbaugh RC, Schultz L; Old Dominion University. Bloom's taxonomy [cited 2009 May 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

NCCPHP = North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness

PHP = public health preparedness

The lowest cognitive level, Remembering, is defined as “retrieving relevant knowledge from long-term memory.” This level is followed by Understanding—“determining the meaning of instructional messages, including oral, written, and graphic communication.” The next level is Applying—“carrying out or using a procedure in a given situation.” The fourth level, Analyzing, refers to “breaking down material into its constituent parts and detecting how the parts relate to one another and to an overall structure or purpose.” The next level is Evaluating—“making judgments based on criteria and standards”—and the highest level is Creating, or “putting elements together to form a novel, coherent whole or make an original product.”20

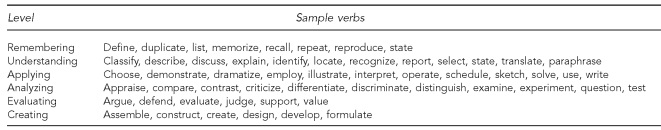

Determining the appropriate cognitive level for a module or course depends on the intended audience, their educational needs, and the time they have available for learning. Figure 3, adapted from a model developed by Old Dominion University,21 provides an example of sample verbs associated with each cognitive level of Bloom's taxonomy (revised version) and is useful for determining appropriate cognitive levels when developing a module or course.

Figure 3.

Verbs associated with cognitive levels of Bloom's taxonomy (revised),a used by the NCCPHP to determine appropriate cognitive levels and develop learning objectives for PHP educational offerings

aOverbaugh RC, Schultz L; Old Dominion University. Bloom's taxonomy [cited 2009 May 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

NCCPHP = North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness

PHP = public health preparedness

The TWS modules are all geared toward achieving a cognitive level of Understanding. Typical objectives for training modules include describing the threat of pandemic influenza, understanding how hurricanes impact communities, and explaining various public health concepts.

The Communicable Disease course is designed to achieve the level of Applying. Participants demonstrate knowledge of surveillance reporting requirements and interpret outbreak data.

The certificate courses are aimed at achieving the highest cognitive level of Creating. Course assignments require students to develop hypothesis-testing questionnaires, formulate policy recommendations, and synthesize and assemble surveillance information from various sources on a particular health outcome.

4. Utilize reusable learning objects

The development of Internet-based teaching materials can be costly and time-consuming. An integral component of the NCCPHP distance-learning strategy is the use of reusable learning objects (RLOs). RLOs can be defined as “small but pedagogically complete segments of instructional content that can be assembled as needed to create larger units of instruction, such as lessons, modules, and courses.”22 Examples of RLOs include recorded lectures, case studies, exercises, and simulations. RLOs, because they are, by definition, reusable, are an effective strategy for maximizing cost efficiency and flexibility.

Examples of RLOs used by NCCPHP include a variety of lectures (which have been recorded, transcribed, and are accompanied by slide presentations) that appear as single modules on the TWS and as lectures for the Communicable Disease and certificate courses. Another example of an RLO is FOCUS on Field Epidemiology, NCCPHP's Internet-based periodical. These issues serve as stand-alone modules on the TWS and are used as resources in the Communicable Disease course and to support exercises and activities in certificate courses.

5. Know the target audience (or partner with someone who does)

When developing Internet-based training modules or courses, it is important to know—or to partner with someone who knows—the target audience, as well as their training needs, technical capabilities, and time commitments. The development of the Communicable Disease course provides an example of a successful partnership between the academic public health community and a state division of public health.11

In 2003, NCCPHP developed and implemented a comprehensive self-assessment survey based on available published competencies.5 This assessment requested that public health workers identify their training needs and rate the importance of different competencies for their jobs. As previously noted, 41% of North Carolina local public health nurses indicated a high need for training in recognizing and responding to a disease outbreak in their communities. The state of North Carolina had also identified training needs for public health nurses around disease reporting requirements. In 2003, a new communicable disease control manual was published for distribution to North Carolina local health departments, and the Communicable Disease Branch (CDB) of the Epidemiology Section at the North Carolina Division of Public Health determined that training on the updated manual was needed. In addition, the CDB identified computer proficiency as a skill needed by public health nurses, because disease reporting would soon be done through an entirely Internet-based system.

Together, the CDB and NCCPHP developed the Communicable Disease course. While NCCPHP provided expertise in distance learning, both entities had strong teaching credentials and content expertise. However, NCCPHP lacked detailed knowledge of the target audience. The CDB was able to fill this void with its knowledge of the strengths and limitations of local health department nurses—information that was critical in tailoring course design and technical support to meet the specific needs of public health nurses in North Carolina. This meant, for example, that coursework should require no more than three to four hours per week, and activities should be designed to be completed in short blocks of time.11

Similar to Communicable Disease course participants, most students in the certificate program are nontraditional (i.e., older, working full time, traveling, and with other life demands). Where appropriate, certificate courses are designed to have maximum flexibility in scheduling. Modules last three to four weeks, and assignments are due at the end of each module. With nontraditional students, an extremely high level of customer service from both the administrative and teaching staff is necessary for success. Students in the certificate program rely on staff to take care of administrative and technical issues to allow them to focus their limited time on their studies.

6. Develop well-organized courses and programs with a standard look and feel

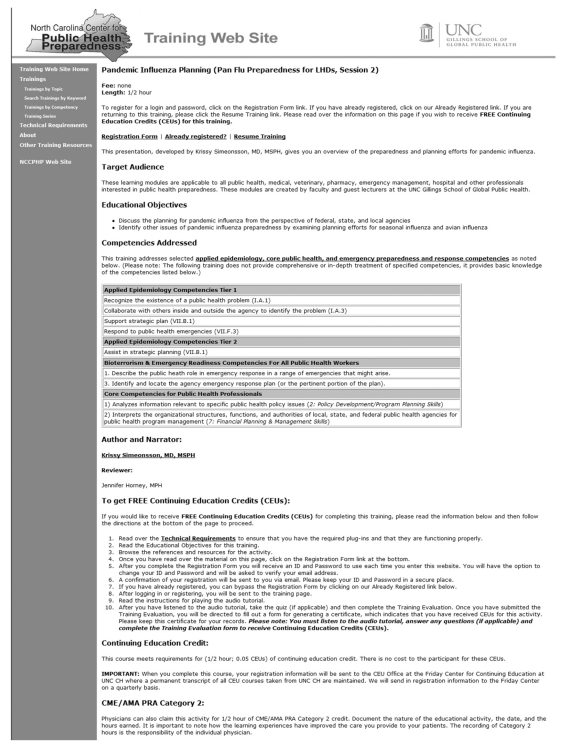

For a training website to be user-friendly and easily navigated, it is important that each training module have a standard look and feel with regard to formatting, font, color scheme, and order of menu items and materials. An example is shown in Figure 4, where each module on the TWS is presented in a similar manner. Upon selecting a module, participants are presented with a brief description of content, the length of time needed to complete the module, a description of the intended target audience, course objectives, and a list of the core public health competencies, AECs, and/or emergency response competencies addressed. After logging in to the site, participants are able to access training modules, which, as previously discussed, all follow a similar course structure. This consistency enables participants to easily navigate among training modules on different topics.

Figure 4.

Sample distance-learning training module overview page from the NCCPHP Training Web Site

NCCPHP = North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness

NCCPHP delivers its longer Internet-based courses, such as the Communicable Disease and certificate courses, via the Blackboard Academic Suite™,23 an Internet-based course management system. The four certificate courses are designed to have a consistent look and feel. Each module includes instructions, as well as folders containing a checklist of all individual activities and their due dates, lectures, readings, case studies, and a group project.

7. Provide readily accessible technical support to participants and students

With distance-learning programs, a high level of readily accessible technical support is essential. An important component of this support is orienting faculty and teaching assistants (TAs) to the special challenges and opportunities involved in distance learning. NCCPHP has developed a formal orientation and manual for TAs involved in online academic courses and provides guidance to faculty on how to interact with distance-learning students via e-mail or discussion boards. Instructors should not assume that all distance-learning participants and students are equally fluent in computer technology, and instructions should outline all steps necessary to use software programs and complete assignments.

The TWS home page contains a link to “Technical Requirements” (Figure 4, upper left corner). This link lists technical requirements and provides a software tutorial for participants. A “Contact Us” link provides an e-mail address for specific technical questions. NCCPHP staff respond to questions or refer issues to the site's Web application developer based at UNC.

The Communicable Disease course links new participants to a customized skills test that checks for the basic computer system requirements, software plug-ins, and participant skills necessary to take an Internet-based course at UNC. Throughout the course, NCCPHP staff provide technical support via e-mail and phone.

Students in the certificate program attend a software orientation conference call held by UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health Blackboard support staff, which includes a brief overview of the program and an Internet-based course orientation that focuses on using Blackboard software, e-mail requirements, computer hardware and software requirements, and who to contact for technical support during the program. Students receive e-mail documents before the call and must have computer access to walk through an example course during the orientation. All students must test their Internet browsers, plug-ins, and navigational skills using an automated Internet-based computer assessment before the course begins. Throughout the course, TAs and the Blackboard support staff provide technical support. In addition, students have access to UNC's Information Technology Services department, which provides technical support for the entire campus. NCCPHP also provides support for special software used in the courses, such as Epi Info™24 and Adobe® Acrobat® Connect™ Pro Meeting.25

8. Manage student and instructor expectations

Students often believe that an Internet-based continuing education or academic course will be easier and less time-consuming than a classroom-based course. This impression is not accurate and must be dispelled at the beginning of each course or program. The certificate courses are designed to have the same rigor as classroom-based courses, and because communication is primarily written rather than verbal, Internet-based courses can take more time than equivalent classroom-based courses. Students in the certificate program read and acknowledge a statement informing them of course expectations, time commitments, deadlines, grading policies, computer issues, and procedures for withdrawing from a course.

Faculty and TAs also need to understand that the volume of written material produced in an Internet-based course can far exceed that of a classroom-based course. In addition to regular assignments, exams, and group projects, Internet-based faculty and TAs must read group discussion-board postings and respond to e-mails. This extra time spent reading can be offset by reduced lecture time, as Internet-based lectures are recorded and can be used for numerous offerings of courses with minor modifications.

Finally, it is critical that instructions and activities be explicitly presented. Students may become frustrated when instructions are vague or incorrect, or while waiting for a clarification from instructors. Ultimately, course success depends on commitment and flexibility from both instructors and students.

9. Provide continuous feedback to participants and students

Participants and students in Internet-based courses require more feedback from faculty and TAs than students in traditional courses. This feedback, which can range from preprogrammed responses to personalized e-mail from faculty and TAs, makes participants feel more connected to the course or learning experience.

Participants taking courses on the TWS receive automatic feedback via a posttest that provides comments on both correct and incorrect answers. In the Communicable Disease and certificate courses, faculty and TAs strive to respond to participant e-mails within 24 hours, and participant feedback is solicited on each module of the course. This feedback is incorporated into course improvement efforts that take place between course offerings.

In the certificate courses, Department of Epidemiology graduate students serve as TAs, with one TA for every two- to three-student group (maximum assistant-to-student ratio is 1:30). TAs work closely with their groups, reviewing case studies; monitoring discussion forums or group projects; and answering questions via e-mail, phone, or Internet videoconferencing. Faculty communicate regularly with students using these same means. Some faculty also send weekly e-mails to students, including information about what is happening in the course that week, discussion of current content-related material in the news, and course updates. To personalize correspondence, some faculty add everyday life information (e.g., about family) and include their photos with their e-mail signatures. E-mails that humanize the instructors have been well received by students.

Feedback is routinely solicited from students throughout the certificate courses. A “Module feedback” link allows students to provide anonymous feedback at the conclusion of each module within each course, and an “Ask the faculty'” link is provided in each course to encourage students to engage with faculty.

10. Continually evaluate, refine, and update course content and delivery

To ensure that training modules and courses are meeting students' needs, courses are continually evaluated, refined, and updated. Each module on the TWS concludes with an anonymous participant evaluation that seeks to measure whether the module effectively addressed listed competencies, provided the information the participant desired, introduced new terminologies and concepts, clarified or reinforced familiar terminologies and concepts, specifically addressed their professional responsibilities, or made them feel better equipped to perform their jobs.

Longer courses provide numerous opportunities for participant evaluation; instructors must determine the optimum level for their specific courses. The Communicable Disease course provides participants with the opportunity to complete an open-ended, anonymous evaluation at the completion of each module. In addition, participants complete an anonymous final course evaluation and a six-month post-course evaluation.

The certificate courses incorporate four types of anonymous student evaluations. During each module within a course, students can evaluate individual instructions, lectures, case studies, and group projects. About one-third of the way through each course, students can evaluate the performance of their graduate TAs. At the conclusion of each course, students complete a final evaluation, which allows them to evaluate faculty, TAs, course content, and their perceived improvement on competencies. Finally, upon completion of the program (all four courses), members of the NCIPH Evaluation Services team evaluate students' satisfaction with the program both immediately following the program and after six months.

Course evaluation by faculty and TAs is also important. Weekly meetings allow faculty and TAs to discuss and review course content and keep up-to-date on student progress and issues in each course. Each module also contains a hidden text box within Blackboard that is only available to faculty and TAs. This text box is used to document problems with course content or instruction and note possible corrections. Small changes are made during the course; more substantial changes are completed before the next offering of the course. The text box facilitates course updates by providing a single common repository for comments from all faculty and staff involved with the course.

Refining and updating courses on a regular basis also provides an opportunity to incorporate new technology that can enhance course content and delivery. An example of a technology update that has been well received by students is the addition of a weekly blog in one of the certificate courses, Principles and Methods of Applied Infectious Disease Epidemiology. The blog, My Favorite Disease, provides interesting information on different infectious diseases and includes epidemiologic information on a “disease of the week” (Figure 5). Another example of a technology update was the addition of Internet videoconferencing using Adobe Acrobat Connect Pro Meeting.25 This technology enables live interaction among faculty, TAs, and students on a regular basis; TAs also use videoconferencing to hold office hours. In addition, NCCPHP has made videoconferencing technology available to students to facilitate the completion of group assignments.

Figure 5.

Sample page from My Favorite Disease, a weekly blog developed for one of the NCCPHP Certificate in Field Epidemiology distance-learning courses

NCCPHP = North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness

CONCLUSIONS

The Council on Linkages reports, “In addition to being economical and easy to use, scholarly research has proven that well-designed distance-learning programs are very effective in transferring skill and knowledge to workers and [have] been shown to beneficially affect the practice of public health programs.”4 In NCCPHP's experience, the 10 guiding principles have been critically important to the effective design and delivery of its Internet-based training modules, continuing education courses, and graduate certificate programs. These principles have been developed and refined during NCCPHP's 10 years of Internet-based PHP educational programming, and may be useful in furthering the discussion regarding the adoption of common principles and practices for public health distance learning.

Footnotes

This article was supported by Cooperative Agreement #U90/CCU424255 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions. Public health workforce study. Washington: HHS; 2005. [cited 2009 May 6]. Also available from: URL: ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/bhpr/nationalcenter/publichealth2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umble KE, Shay S, Sollecito W. An interdisciplinary MPH via distance learning: meeting the educational needs of practitioners. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:123–35. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Institute of Medicine. Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDowell D, Gibbs N Public Health Foundation. Council on Linkages: distance learning in public health. [cited 2009 Aug 26]. Available from: URL: http://www.phf.org/link/LINK12-1DL.htm.

- 5.Harrison LM, Davis MV, MacDonald PD, Alexander LK, Cline JS, Alexander JG, et al. Development and implementation of a public health workforce training needs assessment survey in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(Suppl 1):28–34. doi: 10.1177/00333549051200S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. Epidemiology competencies. [cited 2009 May 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/docs/epi/EpiComps_Nov04.pdf.

- 7.North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness. A report on the public health workforce in North Carolina. Chapel Hill (NC): University of North Carolina Printing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. 2004 national assessment of epidemiologic capacity: findings and recommendations. [cited 2009 May 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/Assessment/ECA/pdffiles/ECAfinal05.pdf.

- 9.Gebbie KM, Turnock BJ. The public health workforce, 2006: new challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:923–33. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horney JA, MacDonald P, Rothney EE, Alexander LK. User patterns and satisfaction with online trainings completed on the North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness Training Web Site. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;(Supp1):S90–4. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander LK, Dail K, Horney JA, Davis MV, Wallace JW, Maillard JM, et al. Partnering to meet training needs: a communicable-disease continuing education course for public health nurses in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 2):36–43. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald PD, Alexander LK, Ward A, Davis MV. Filling the gap: providing formal training for epidemiologists through a graduate-level online certificate in field epidemiology. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:669–75. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core competencies for public health professionals. [cited 2009 Jul 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.phf.org/link/corecompetencies.htm.

- 14.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core competencies for public health professionals: a practical tool to strengthen the public health workforce. The Link. 2001;15:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebbie K, Merrill J. Public health worker competencies for emergency response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. CDC/CSTE applied epidemiology competencies—toolkit. [cited 2009 May 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/competencies.asp.

- 17.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. 2006 national assessment of epidemiologic capacity: findings and recommendations. [cited 2009 Oct 27]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/pdffiles/2007/2006CSTEECAFINALFullDocument.pdf.

- 18.Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, editors. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloom BS, editor. Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook 1: the cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company, Inc.; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krathwohl DR. A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: an overview. Theor Pract. 2002;41:212–64. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overbaugh RC, Schultz L. Old Dominion University. Bloom's taxonomy. [cited 2009 May 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm.

- 22.Hamel CJ, Ryan-Jones D. Designing instruction with learning objects. [cited 2009 May 28];Int J Educ Technol [serial online] 2002 3(1) Also available from: URL: http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ijet/v3n1/hamel. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackboard Inc. Blackboard Learning System™: Release 8.0.475.0. Washington: Blackboard Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Epi Info™: Version 3.5.1. Atlanta: CDC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe® Acrobat® Connect™ Pro Meeting: Version 7.5 r128. San Jose (CA): Adobe Systems Incorporated; 2010. [Google Scholar]