SYNOPSIS

Service learning is one way that academia can contribute to assuring the public's health. The University of North Carolina's Team Epi-Aid service-learning program started in 2003. Since then, 145 graduate student volunteers have contributed 4,275 hours working with the state and local health departments during 57 activities, including outbreak investigations, community health assessments, and emergency preparedness and response. Survey data from student participants and public health partners indicates that the program is successful in meeting its goal of creating effective partnerships among the university, the North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness, and state and local health departments; supplying needed surge capacity to health departments; and providing students with applied public health experience and training. In this article, we discuss the programmatic lessons learned around administration, maintaining student interest, program sustainability, and challenges since program implementation.

The public health workforce in the United States is in decline. The workforce is both aging quickly and getting smaller.1 The average age of state public health employees is almost 47 years, with, on average, 24% eligible for retirement. In some states, as much as 45% of the workforce is eligible for retirement.2 Severe shortages in certain public health concentrations and high turnover rates further exacerbate the problem. A 2006 assessment of epidemiologic capacity by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists found that 2,436 epidemiologists are currently working in the U.S.; however, 3,172 (a 30% increase) are needed to reach ideal capacity.3 The number of epidemiologists did not increase from the 2004 to the 2006 assessment, indicating that the number of new graduates entering these positions is not yet sufficient to fill the gap.4,5 In addition to decreasing in size, the public health workforce is also remarkably undereducated, especially in select areas. Approximately half of the epidemiologists in 2006 (55%) had an epidemiology degree.3 Without direct intervention, the situation is not likely to improve. While almost 7,000 students graduated from accredited schools of public health in 2004, most seek jobs outside traditional public health agencies.6

In its 2002 report, the Institute of Medicine cited service learning as one way that academia contributes to assuring the public's health. The criteria outlined by the report for a service-learning experience are: (1) the service must be relevant and meaningful to all stakeholder parties and must be provided in the community, (2) the service must not only serve the community but also enhance student academic learning, and (3) the service must also directly and intentionally prepare students for active civic participation in a diverse democratic society.7

In January 2003, the North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness (NCCPHP), a program of the North Carolina Institute for Public Health (NCIPH), established the Team Epi-Aid program.8 Team Epi-Aid recruits and places students from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Gillings School of Global Public Health (hereafter, School) in the North Carolina Division of Public Health (NC DPH) and local health departments throughout North Carolina to assist with outbreak investigations and other short-term applied public health projects. Team Epi-Aid is a service-learning program that provides state and local health departments with workforce surge capacity and students with an opportunity to gain practical public health experience. Other schools of public health have similar graduate student epidemiology response programs (GSERPs).

A previously published article describes the Team Epi-Aid program implementation, training, response protocol, and activities for 2003–2004.8 In summary, NCCPHP began the Team Epi-Aid program after discussions with the dean of the School, the state epidemiologist, the state public health preparedness coordinator, staff from NCCPHP and NCIPH, and faculty from the School's Department of Epidemiology. Team Epi-Aid is funded, organized, and administered through NCCPHP. Partners for the program include the state and local health departments, which receive help with outbreak investigations, disaster response, surveillance and data analysis, emergency preparedness exercises, and training. Volunteers in Team Epi-Aid include graduate students, non-degree students, and staff, primarily at the School, but also from the UNC School of Medicine.

To volunteer for Team Epi-Aid, students are required to take three online training modules. Two address outbreak investigation, and the third is a course in the protection of human research subjects. NCCPHP also offers suggested online training modules, face-to-face training seminars during the semester, and activity-specific trainings on an as-needed basis.

Local and state health departments request Team Epi-Aid assistance through NCCPHP. NCCPHP recruits student volunteers through the e-mail listserv and coordinates activity logistics, serving as a liaison between the requesting agency and the volunteers. Training may be provided by the requesting agency or NCCPHP. Program evaluation is conducted by NCCPHP.

This article summarizes participant and public health practice partner evaluation data for the Team Epi-Aid program from January 2003 through September 2009. Furthermore, we discuss programmatic lessons learned, challenges since implementation, and sustainability issues.

METHODS

Participants

All students in the schools of Public Health and Medicine are eligible to participate in Team Epi-Aid. At the start of each school year, there is a program orientation, and students can sign up while attending the orientation or via e-mail. There is no membership selection process; all interested students are accepted. NCCPHP maintains a Microsoft® Access database and e-mail listserv of students who have signed up for Team Epi-Aid. Information in the database includes name, department, computer skills, language skills, type and level of public health experience, access to transportation for fieldwork, and experience with outbreak investigation. Unless health department partners request students with specific skills, participation in each activity is on a first-come, first-served basis. Team Epi-Aid members are not obligated to participate in activities. The database is updated annually to indicate status as “inactive” for students who have graduated. In addition, the database includes information about each Team Epi-Aid activity. We limited discussion in this article to activities in which students volunteered; activities involving only NCCPHP staff were excluded.

Data collection

Three components are in place to evaluate the Team Epi-Aid program: activity-specific reports from students and public health department partners and an annual student satisfaction survey. All surveys have been approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Following each Team Epi-Aid activity, participating students submit an activity report via e-mail. The activity report queries basic information about the activity, such as number of hours contributed and tasks performed. It also includes yes/no questions about potential impact, including whether the activity sparked the student's interest in an applied public health career. Information about how the activity could have been improved is collected using a pick list. In 2003 and 2004, administration of the activity report form was not well documented. For this review, we considered a form to be missing if there was no indication of tasks performed by the student.

At the conclusion of each Team Epi-Aid activity, health department partners receive an e-mail request to participate in a satisfaction survey. An e-mail reminder is sent one to two weeks later to non-respondents. The partner survey queries satisfaction with various aspects of the activity, including knowledge of student volunteers, ability of Team Epi-Aid to meet surge capacity needs, and overall Team Epi-Aid experience. Responses are assessed using a four-point Likert scale ranging from “very satisfied” to “very unsatisfied.” Partners are also asked yes/no questions about whether Team Epi-Aid met its stated goals and whether they would request future assistance. The partner survey was initiated in January 2005 and is administered online via surveymonkey.com.

The final evaluation component is an annual survey of Team Epi-Aid members, including those who have not participated in any activities. Students are invited to respond anonymously to the survey via e-mail in late spring (end of the semester). E-mail reminders are sent one and two weeks following the initial request. The survey includes questions about activity participation (number and type of activities), new knowledge or skills gained, and overall program satisfaction. Satisfaction is assessed using a four-point Likert scale ranging from “very satisfied” to “very unsatisfied.” Students who did not participate in activities are asked to indicate their primary reason for not participating. The survey, administered online via surveymonkey.com, was conducted in 2005, 2007, 2008, and 2009. All years were combined for this review. Because students who were members for multiple years could have responded to the survey more than once, using the number of student members as a denominator could lead to an artificially high response rate. Therefore, we report only the number of respondents for this survey.

RESULTS

Participants

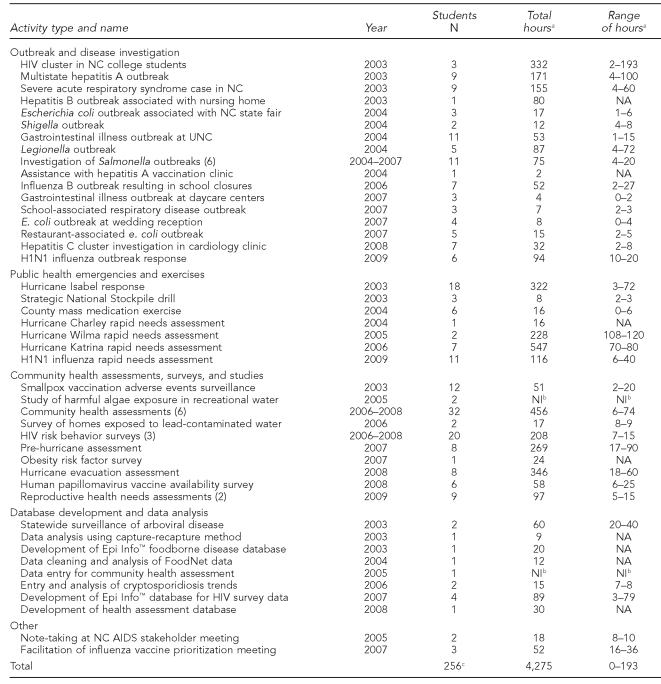

From January 2003 through September 2009, 145 unique students contributed 4,275 hours to 57 Team Epi-Aid activities, including community health assessments, surveys, and studies (35.7% of hours); public health emergencies and exercises (29.3% of hours); outbreak and disease investigations (27.9% of hours); database development and data analysis (5.5% of hours); and other (1.6% of hours). Specific activities and associated number of students and hours contributed within these categories are listed in Table 1. Because many students participated in multiple activities and were counted as participants more than once, there are a total of 256 instances of student participation.

Table 1.

Student participation in UNC Team Epi-Aid GSERP activities, by activity type and year, January 2003–September 2009

aHours rounded to nearest whole number; total reflects actual sum

bNot included due to missing data

cNumber represents the instances of student participation; a person who volunteered multiple times was counted each time he or she participated.

UNC = The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

GSERP = graduate student epidemiology response program

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NC = North Carolina

NA = not applicable

NI = not included

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Activity report forms

Of the 256 instances of student participation from January 2003 through September 2009, 214 (83.6%) activity report forms were returned. Students who volunteered were primarily from the School, representing all departments: epidemiology (n=105; 49.1%), environmental sciences and engineering (n=33; 15.4%), maternal and child health (n=19; 8.9%), health behavior and health education (n=18; 8.4%), nutrition (n=8; 3.7%), health policy and management (n=5; 2.3%), public health leadership program (n=3; 1.4%), and biostatistics (n=3; 1.4%). Remaining volunteers (n=20; 9.3%) were from the School's certificate programs and the schools of Medicine and Nursing (data not shown).

The most common activities reported by student volunteers were data collection (n=161; 75.2%), data entry (n=56; 26.2%), data analysis (n=13; 6.1%), and surveillance (n=13; 6.1%). Other tasks included database and questionnaire design, documentation, disaster clean-up, and participation in preparedness exercises (data not shown).

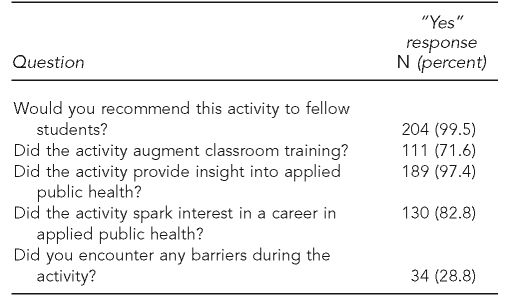

Student volunteer feedback about their experiences was positive overall (Table 2). Approximately one-quarter of volunteers encountered a barrier during their activity; the most commonly cited barrier (n=25; 73.5%) was interview nonresponse during surveys, either because people were not home, refused to complete a survey, or couldn't respond due to language barriers. Few students (n=48; 22%) indicated areas for activity improvement. Of those, most (n=40; 83.3%) cited “being more involved in other aspects of the project.”

Table 2.

UNC Team Epi-Aid GSERP volunteer feedback from activity report forms, January 2003–September 2009 (n=214)a

aQuestion-specific sample size reflects missing values and differing years of question administration; answer options for questions were “yes” or “no.”

UNC = The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

GSERP = graduate student epidemiology response program

Partner satisfaction

Fifty-seven public health departments requested assistance from January 2003 through September 2009. Of 57 public health department partners, 37 (64.9%) completed the partner satisfaction survey. Among respondents, the majority agreed that Team Epi-Aid met its stated goals:

To create effective partnerships among the School, NCCPHP, and state and local health departments (n=34; 91.9%);

To supply needed surge capacity to state and local health departments (n=32; 86.5%); and

To provide students with applied public health experience and training (n=35; 94.6%).

All partners were “very satisfied” (n=28; 75.7%) or “somewhat satisfied” (n=9; 24.3%) with their overall Team Epi-Aid experience, and all would request Team Epi-Aid assistance again in the future. In addition, two branches of NC DPH and two local health departments requested Team Epi-Aid assistance multiple times from January 2003 through September 2009.

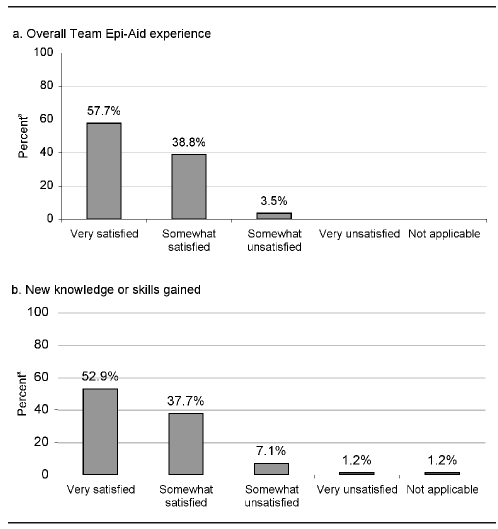

Annual program satisfaction survey for students

There were 168 Team Epi-Aid members who completed the annual student satisfaction survey from January 2005 through September 2009. More than half of the respondents (n=89; 53.0%) participated in at least one activity. Of those who did not participate (n=79), the primary reason for not participating was “not [having] enough time” (n=57; 72.2%). The next most common reasons were “did not have required experience” (n=4; 5.1%) and “did not hear about opportunities” (n=4; 5.1%). The latter was noted among students who had recently joined the program. Among participating students, the majority were “very satisfied” (57.7%) or “somewhat satisfied” (38.8%) with their Team Epi-Aid experience (Figure).

Figure.

UNC Team Epi-Aid GSERP student volunteer satisfaction, 2005, 2007–2009 (n=85)

aPercentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

UNC = The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

GSERP = graduate student epidemiology response program

DISCUSSION

Program evaluation data from January 2003 through September 2009 demonstrate the wide variety of projects in which Team Epi-Aid volunteers have participated. The number of volunteer hours alone (4,275 hours) is a testament to program success. However, satisfaction data from student volunteers and health department partners provide the strongest evidence of the value and impact of the program.

Health departments benefit from these programs, particularly amid shortages within the public health workforce. These agencies get motivated, fast-learning student volunteers who are in the midst of academic training relevant to the health department's needs. This is especially critical for health departments lacking in-house epidemiology capacity. Students also bring valuable skills in languages, study design, data analysis, statistical software programs, environmental health, and qualitative research.

The importance of Team Epi-Aid to health department partners is exemplified by the Men's Health Survey, which is organized by the Communicable Disease Branch at NC DPH. For three years in a row (2006–2008), NC DPH requested Team Epi-Aid assistance to conduct in-person interviews with men who have sex with men at North Carolina Pride, an annual festival celebrating gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals. One NC DPH partner noted, “The liaison and students were both enthusiastic about our project and extremely professional. Our event would not have been as successful as it was without their help. Team Epi-Aid is an invaluable resource!”

Program administration

We have learned multiple lessons from administering this program since its inception in January 2003, including approaches to overcoming challenges related to program administration, maintaining student engagement, and program sustainability.

It is critical to have a single point of contact as the Team Epi-Aid liaison/leader. Having NCCPHP administer the program and having one person designated as the program coordinator has been essential to maintain continuity within the program and with external partners. NCCPHP administration of the program ensures that neither the health department nor the student has to coordinate logistics such as dates, volunteer schedules, location, travel, or food. Some other GSERPs use an alternate model where students, rather than staff, serve as program administrators or they are co-led with students, faculty/staff, and local health department staff. However, we have found that significant staff and faculty time is required to manage the program and supervise student volunteers. We estimate that coordinating and managing the Team Epi-Aid program requires a 30%–50% full-time equivalent and a faculty sponsor for 10% effort. Further, having the program run by NCCPHP allows the program to build continuity over time, to strengthen itself by maintaining partnerships with local health departments, and to build partnerships for other activities and programs, such as more formalized practica, internship, or mentorship programs.

Occasionally, students initially commit to participating in an activity, only to withdraw close to the event date, often because of academic demands. This presents a challenge to NCCPHP and risks leaving the requesting agency without needed support. To address this problem, during the annual orientation and prior to each activity, we have emphasized the importance of making firm commitments. We send reminder e-mails prior to each activity to confirm all volunteers. Finally, we notify the requesting agency immediately when the number of volunteers changes.

Protecting students from potential illness or injury during volunteering is essential. For Team Epi-Aid projects that require travel or overnight stays, an experienced NCCPHP staff member is always present for supervision. Students are briefed on the potential risks—to both physical and mental health—of any volunteer assignment and will often be asked to sign a waiver by the state or local health department. In addition, we have worked with the university's legal counsel to assure that student volunteers are covered for liability purposes. While it can be challenging to navigate the legal aspects of having students volunteer, many states have liability protection for volunteers who assist during a public health emergency response.9 For more routine activations, it is important that students and health departments understand the legal implications of working as a volunteer.

Protecting the privacy of patients or study participants is also a priority. Student volunteers may have access to protected health information, as defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.10 All Team Epi-Aid volunteers are required to complete the Collaborative Institute Training Initiative's Program for the Protection of Human Research Subjects online course prior to taking part in an activity.11 Some health department partners also require student volunteers to sign a confidentiality agreement.

Information about the administration of Team Epi-Aid and guidelines for partner collaboration are included in a written protocol, which can be shared with health department partners. A more detailed version of the protocol is used internally by NCCPHP staff. In addition, we have developed volunteer guidelines that are essentially a student-oriented, concise version of the protocol. These documents ensure that both volunteers and requesting agencies have clear expectations about the role of Team Epi-Aid.

The surge capacity provided by Team Epi-Aid may augment existing staff efforts. While unions are not prominent in North Carolina, in some states and localities, unions may exist and may not support this type of program, as student volunteers may jeopardize possible overtime hours and pay for unionized public health staff. Team Epi-Aid and other student response teams should not be viewed as an effort to replace full-time staff or put at risk their opportunities to receive overtime hours and pay.

Maintaining student interest

Recruiting student members and maintaining their interest is a critical aspect of the Team Epi-Aid program. Typically, there is a high level of student interest in the Team Epi-Aid program at orientation sessions at the start of each academic year. As the semester progresses and students get immersed in coursework, it can be difficult to maintain student interest in the program. Volunteer recruitment can be particularly difficult during exams, school holidays, or other major university activities. If volunteer response is not sufficient to fill a request, NCCPHP staff may respond when available, or, in rare instances, the health department request is declined.

One area for improvement noted by student volunteers is being involved with more aspects of a project, rather than a single piece. For example, during an outbreak investigation, students may want to conduct interviews in a case-control study and analyze data, rather than simply entering data or calling controls for a case-control study. It is important that student volunteers have the opportunity to gain experience in a range of applied public health tasks, especially in areas not typically addressed through academic courses.

To sustain interest, we found that Team Epi-Aid members, even those who do not participate, appreciate receiving updates about Team Epi-Aid activities. Updates may include study results, as well as abstracts or manuscripts that may have resulted from an activity. In some years, students who are the most active participants in Team Epi-Aid have received prizes for their participation, including gift certificates to the UNC Health Affairs Bookstore or a trip to the annual scientific conference of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Epidemic Intelligence Service.

When Team Epi-Aid was founded in 2003, efforts were made to differentiate the program from more traditional internships, mentorships, or practicums where students had more long-term assignments with the state or local health departments. For these longer assignments, the sponsoring agency generally provides the student with additional guidance and supervision. Although it is not the main purpose of the program, it is possible for some students (depending on the department) to fulfill practicum requirements through Team Epi-Aid activities. If students use a Team Epi-Aid activity to fulfill their practicum requirement, the NCCPHP program administrator or another staff member must serve as a practicum preceptor for the student and complete required evaluation forms.

Program sustainability

Schools of public health have responded to the call for training more public health students and providing opportunities to interact with public health practice in many ways. GSERPs are one such way in which schools are providing public health practice learning experiences for their students.12 Similar to UNC's Team Epi-Aid program, GSERPs exist (or have existed) at other schools, including Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, The University of Texas School of Public Health, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health,13 University of Michigan School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center College of Public Health, Saint Louis University School of Public Health, University of South Carolina Arnold School of Public Health, The Ohio State University College of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, and Harvard School of Public Health. These programs are similar but have developed independently, so differences exist among them. Many partner with their local or state health departments, while others have additional partners, such as the Medical Reserve Corps. Many schools have programs that are open to all graduate students in the school of public health, while at least one has an application process.

In 2010, support for many GSERPs, including UNC's Team Epi-Aid program, is linked primarily to the Centers for Public Health Preparedness (CPHP) program funded by CDC. The future of the CPHP program is unknown at this time. There is a risk that, without funds from their respective CPHP programs, many schools will not be able to sustain their GSERPs. Obtaining funding from other sources, such as the university, public health practice partners, and foundations, should be a priority. Some schools have diversified where their operating funds come from, such as from teaching grants, city/county grants, their university's budget, donation of faculty and staff time, and university-related funding for student groups. Connecting GSERPs from various universities through some formal structure might build future momentum for these programs. This could be a good way to get recognition from CDC, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the National Association of County and City Health Officials, and other agencies/organizations with potential funds for this type of service-learning program.

To provide consistency among GSERPs and assist with marketing the programs to funders, public health practice partners, and students, GSERPs could explicitly link training and activities to public health competencies, such as the Applied Epidemiology Competencies (AECs) developed by CDC and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists.14–16 Programs could also address the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals developed by the Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice.17 Evaluation of the programs could include students' self-assessments of competency around select AECs or other relevant competencies. Another option is to require student volunteers to become trained as community-disaster responders or certified in recognized programs, such as the National Incident Management System, so they can integrate easily with public health partners during a public health response.

CONCLUSIONS

Team Epi-Aid continues to achieve its goals of providing public health workforce surge capacity and offering opportunities for students to gain practical experience. Based on six years of evaluation data, Team Epi-Aid has effectively achieved its goals of creating partnerships, providing public health workforce surge capacity, and offering opportunities for students to gain practical experience. Ensuring sustainability of the program is essential to continue meeting these goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the North Carolina Division of Public Health leadership for overall support of this program and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill students and faculty and North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness staff who have participated in the program since its inception in 2003.

Footnotes

This article was supported by Cooperative Agreement #U90/CCU424255 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenstock L, Silver GB, Helsing K, Evashwick C, Katz R, Klag M, et al. Confronting the public health workforce crisis: ASPH statement on the public health workforce. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:395–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. State public health employee worker shortage report: a civil service recruitment and retention crisis. Washington: ASTHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulton ML, Lemmings J, Beck AJ. Assessment of epidemiology capacity in state health departments, 2001–2006. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009;15:328–36. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181a01eb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. 2004 national assessment of epidemiologic capacity: findings and recommendations. Atlanta: CSTE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. 2006 national assessment of epidemiologic capacity: findings and recommendations. Atlanta: CSTE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perlino CM. Workforce brief. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2006. The public health workforce shortage: left unchecked, who will be protected? [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald PD. Team Epi-Aid: graduate student assistance with urgent public health response. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(Suppl 1):35–41. doi: 10.1177/00333549051200S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pestronk RM, Kamoie B, Fidler D, Matthews G, Benjamin GC, Bryan RT, et al. Improving laws and legal authorities for public health emergency legal preparedness. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36(1 Suppl):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Pub. L. No. 104-191, 104 Stat. 3103 (Aug. 21, 1996) [cited 2010 Jun 24]. Also available from: URL: http://aspe.hhs.gov/admnsimp/pl104191.htm.

- 11.Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative. About the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) [cited 2009 Oct 27]. Available from: URL: https://www.citiprogram.org/aboutus.asp?language=english.

- 12.Association of Schools of Public Health. Graduate student epidemiology response programs at Centers for Public Health Preparedness. [cited 2010 Jun 24]. Available from: URL: http://preparedness.asph.org/cphp/documents/GSRP.pdf.

- 13.Gebbie EN, Morse SS, Hanson H, McCollum MC, Reddy V, Gebbie KM, et al. Training for and maintaining public health surge capacity: a program for disease outbreak investigation by student volunteers. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:127–33. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birkhead GS, Davies J, Miner K, Lemmings J, Koo D. Developing competencies for applied epidemiology: from process to product. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 1):67–118. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Competencies for applied epidemiologists in governmental public health agencies. Atlanta: CDC/CSTE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thoroughman D. Applied epidemiology competencies: experience in the field. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 1):8–10. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core competencies for public health professionals. [cited 2010 Jun 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.phf.org/link/Core-Competencies-for-Public-Health-Professionals-ADOPTED-061109.pdf.