SYNOPSIS

The Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness exercise program has two aims: (1) educating the public health workforce on key public health system emergency preparedness issues, and (2) identifying specific systems-level challenges in the public health response to large-scale events. Rigorous evaluation of 38 public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) exercises employing realistic scenarios and reliable and accurate outcome measures has demonstrated the usefulness of PHEP exercises in clarifying public health workers' roles and responsibilities, facilitating knowledge transfer among these individuals and organizations, and identifying specific public health systems-level challenges.

During the past decade, the agencies, organizations, institutions, and individuals that are collectively responsible for ensuring the nation's public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) have developed and revised emergency operations plans, acquired new information-sharing technologies, hired additional key emergency-response personnel, and enhanced preparedness training programs, among other initiatives, to improve their readiness for disasters.1 Yet, because of the relative rarity of major public health threats, it often remains unknown whether public health personnel are trained in the appropriate response plans and procedures, how well the new equipment such as communications or surveillance systems function, or the degree to which public health plans are integrated with the capabilities of other emergency responders such as law enforcement, fire services, emergency medical services (EMS), emergency management, hospitals, and health centers.

As part of their increased efforts in the field of PHEP, public health agencies and other organizations involved in PHEP have increasingly turned to exercises that simulate emergencies. The 2008 National Profile of Local Health Departments (LHDs), for instance, reported that in the year prior to the survey, 86% of LHDs had participated in a tabletop exercise, 72% in a functional exercise, and 49% in a full-scale exercise.2 Previous research has documented that preparedness exercises are effective in familiarizing personnel with emergency plans, allowing different agencies to practice working together, and identifying gaps and shortcomings in emergency planning.3 As proxies for actual emergencies, exercises can provide opportunities to identify how various elements of the public health system interact in response to a challenge, allowing for evaluation of specific, systems-level capabilities in preparedness. In addition, exercises can be used to evaluate the performance of individuals, specific agencies, or an overall (multi-agency) system.4,5

However, the majority of exercises held by public health agencies are not evaluative in nature, but rather intended for purposes of training6–10 or relationship building.11 For instance, in the 2008 National Profile, 76% of the LHDs that participated in exercises reported that they revised their written emergency-response plans based on recommendations from an exercise after-action report (AAR).2 While useful for these purposes, our experience has shown that exercises also provide an opportunity to accurately and reliably measure PHEP performance capabilities and use these measures as part of quality improvement efforts to identify deficiencies and discover their root causes.

The Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness (HSPH-CPHP) exercise program was launched in response to its public health partners' requests for an exercise program that served their needs in evaluating capabilities and advancing preparedness. As part of the exercise program, HSPH-CPHP supplies content expertise relevant to simulating a public health emergency, develops exercise scenarios and supporting documentation, creates evaluation plans and corresponding instruments, and provides trained personnel to facilitate exercise play and evaluate participants' collective performance.

This article describes the lessons learned through this exercise program. In particular, the program was assessed with regard to its effectiveness in meeting two aims: (1) educating the public health workforce on key public health system emergency preparedness issues, and (2) identifying specific systems-level challenges in the public health response to a large-scale event. This article includes both summaries of work published elsewhere and new analyses of participant data not previously published.

METHODS

Type of exercises performed

From 2005 to 2009, the HSPH-CPHP exercise program developed and led 38 exercises including tabletop, functional, and full-scale exercises as well as drills. Each of these exercises conformed to the standards of the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP),12 and was consistent with the principles of the National Incident Management System.13 These exercises were (1) focused on response to a public health threat; (2) realistic to the greatest extent possible and based on up-to-date knowledge of transmission dynamics, preventive measures efficacy, and health outcomes; (3) multidisciplinary and relevant to representatives of public safety (fire, police, and EMS personnel), emergency management, government, and other response agencies whenever possible; (4) regional, involving adjacent municipalities and/or jurisdictions whenever possible; and (5) structured to assess and improve performance as well as educate and inform the participants about PHEP issues.

Evaluation methodology

Evaluation of each exercise included (1) facilitators charged with the task of moderating participants' discussion to focus on the salient issues, (2) evaluation experts who developed the evaluation instruments according to the exercise objectives and scenario, and (3) external evaluators who were responsible for assessing and documenting all communications initiated/received, public information issued, strategic decisions made, and resources requested/deployed during the exercise. Following the exercise, qualitative and quantitative data were collected from participants, facilitators, and evaluators. The results were compared to ensure inter-observer reliability, and any discrepancies were resolved during an evaluator debriefing.

Next, all observed actions, evaluator comments, and results of the data analysis were transcribed onto a master integrated timeline to reconstruct all exercise events and provide the basis for the AAR. AARs were written in a format consistent with HSEEP guidelines. Draft AARs were distributed to the exercise participants, who were expected to create an improvement plan based upon the comments and proposed action items reported within the final AAR.

Data sources

The exercise program has developed several types of evaluation instruments in accordance with the specific objectives of each exercise. Quantitative or qualitative data analysis techniques have been used, depending on the source of data and scope of the evaluation.

To assess the impact of the exercise program in educating the public health workforce on key public health system emergency preparedness issues (Aim 1), we used the following two evaluation approaches:

We surveyed participants with a post-exercise evaluation to assess whether awareness of agencies' roles and responsibilities was improved.

We surveyed participants before and after a specific exercise event to assess knowledge and confidence gained on specific PHEP issues.

To assess the impact of the exercise program in identifying systems-level challenges in the public health response to a large-scale event (Aim 2), we used the following evaluation approaches:

We performed a content analysis of the compendium of AARs produced by the exercise program.

We surveyed participants and external evaluators after the exercises to assess the public health system performance on specific public health system response capabilities in accordance with each exercise's specific objectives.

Data analysis

We performed statistical analysis on the data collected by the previously mentioned evaluation methodologies using SPSS® version 16.0.14 Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests were applied to the data to identify differences across categories of respondents (alpha value was set at 0.05). We performed content analysis on the compendium of AARs produced by the exercise program.

RESULTS

Population characteristics and setting

Since 2005, the HSPH-CPHP exercise program has conducted 38 exercises involving more than 218 cities and towns and reaching more than 5,892 participants. Exercises conducted through this program included 27 tabletop exercises (discussion-based), six functional exercises (operations-based), three full-scale exercises, and two drills. The analysis presented in this article refers mostly to data gathered during discussion-based exercises.

A post-exercise survey was administered to the participants of the discussion-based (tabletop) exercises and was completed by 1,145 participants. Of those surveyed, 63% reported their organizational affiliation, which included the following: health-care organizations (30%), health departments (17%), emergency management agencies (12%), fire departments (8%), law enforcement (6%), schools (6%), volunteer organizations (6%), town administration (3%), federal government (3%), community health centers (2%), and other (7%).

Aim 1: Education of the public health workforce on key public health system emergency preparedness issues

Improved awareness of agencies' roles and responsibilities.

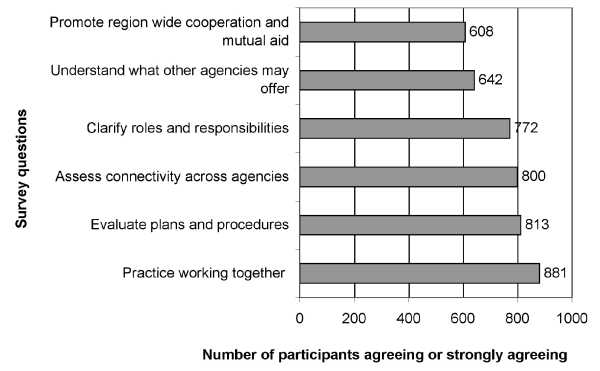

As illustrated in Figure 1, respondents reported agreeing or strongly agreeing that the exercise program was effective in achieving the following: practicing working together to respond to an emergency (n=881, 77%), providing an opportunity to evaluate plans and procedures (n=813, 73%), assessing connectivity within and across agencies (n=800, 70%), clarifying the participants' understanding of their agency's role and responsibility during a public health emergency (n=772, 69%), increasing knowledge of what other agencies may have to offer in terms of resources and assets (n=642, 56%), and promoting region-wide cooperation and mutual aid (n=608, 53%).

Figure 1.

Participants' satisfaction with the exercise program (n=1,145), Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness PHEP exercise program, 2005–2009

PHEP = public health emergency preparedness

Although we found no significant differences by organization, responses differed between participants attending exercises designed to assess a regional response to a public health emergency compared with those attending exercises focused on a single institution's or agency's response. In particular, regional-response exercise respondents reported higher levels of satisfaction with the effectiveness of the exercise program in increasing participants' understanding of agencies' roles and responsibilities (t-test, p<0.001), providing the right environment to practice working together (t-test, p<0.001), and promoting region-wide cooperation and mutual aid (t-test, p=0.001). Participants in regional exercises also felt more engaged in the exercise itself (t-test, p=0.006) and were satisfied that the event had the right mix of disciplines (t-test, p<0.001). No difference was found by organizational affiliation related to knowledge gained or satisfaction with the program (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction, p>0.05).

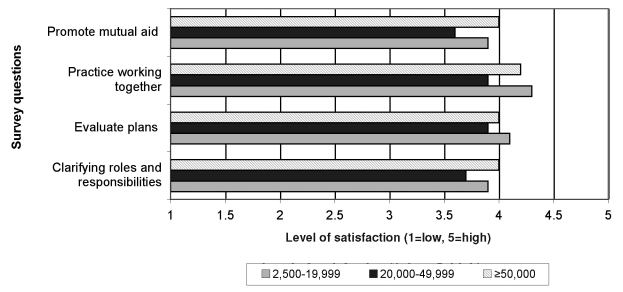

When data were compared according to the population of the community served by the participating agencies (Figure 2), participants from small towns (2,500–19,999 residents) and large towns (≥50,000 residents) reported the highest levels of satisfaction with the effectiveness of the exercise in clarifying their roles and responsibilities, evaluating plans, practicing working together, and promoting mutual aid agreements compared with participants from medium-size towns (20,000–49,999 residents) (ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction, p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Participants' satisfaction with the exercise program by population size, Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness PHEP exercise program, 2005–2009

PHEP = public health emergency preparedness

Knowledge and confidence gained on specific PHEP capabilities.

Some exercises were supplemented by workshops or other didactic experiences in conjunction with exercise play to enhance participants' experience with the exercise and their knowledge of preparedness issues. In one such example, a workshop preceded a tabletop exercise to provide an opportunity for state and local authorities in Massachusetts to learn about and assess the presence of legal authorities needed to implement social-distancing measures in the event of a pandemic. Participants were surveyed before and after the event to assess their knowledge about and confidence in those legal authorities. The results showed that this approach was successful in increasing the knowledge of authorities: on average, the proportion of questions about the authorities that participants were able to answer after the exercise increased by 25%. Furthermore, after the event there was a mean 12% increase in the proportion of participants reporting that legal authorities were available and sufficient, demonstrating an increased level of confidence as well.15

Aim 2: Identification of systems-level challenges in the public health response to a large-scale event

To assess the impact of the exercise program on the identification of systems-level challenges, we conducted a content analysis of the compendium of AARs produced by the tabletop exercise program. This analysis uncovered several categories of systems-level challenges that were regularly observed. For example, regarding leadership and management, challenges identified included the following: (1) errors in understanding individual and agency roles and responsibilities (including insufficient knowledge of the capabilities and assets of responding partners), (2) inconsistent coordination among responders, (3) operational and ethical challenges faced in the decision-making process with significantly limited integration of public health expertise into the response community's decision-making, and (4) difficulties in identifying strategies to reduce staff absenteeism.

With regard to communication capabilities, the following challenges were identified: (1) limited communications capabilities, especially with regard to sharing information about health risks among agencies; (2) the difficulty in communicating, under uncertain conditions, health risks to the public; and (3) insufficient activation of the Health Alert Network.16

Regarding surveillance and epidemiology capabilities, the following were identified: (1) limited ability to track patients and (2) limited laboratory capacity. In disease control, concerns about the efficacy and availability of personal protective equipment were frequently raised. Finally, with respect to mass care, surge capacity was the most common challenge.3

In addition to content analysis, we used a statistical approach to analyze data gathered from participants and external evaluators attending these exercises. For example, we analyzed data from 179 participants who attended a series of tabletop exercises in Massachusetts and Maine and completed the self-assessment performance evaluation, and compared it with data from eight trained external evaluators who observed the communities' performance during the exercise. The consistency of results found from participants to external evaluators suggests the validity of the measurement approaches and their usefulness in identifying specific capabilities within the public health system that need improvement.17

In some of the analyses, the characteristics of the communities participating in the tabletop exercises were taken into consideration. For example, data from 133 public officials participating in an exercise designed to assess risk-communication capabilities during a pandemic influenza were grouped by the size and diversity of the population of the communities served by the participating agencies (measured by percentage of non-English speakers of the community served by their agency). Participants assessed their public health system's capability to communicate with the public to (1) provide up-to-date outbreak information, disease control requirements, individual risk-reduction information, and information on when and where to seek care; (2) minimize people's fear; and (3) reach marginalized populations through trusted sources. For all three aims, risk-communication capabilities were perceived to be greater in communities with less than 10% of the population speaking a language other than English at home, decreasing as the percentage grew to 20% (ANOVA, p≤0.02).

With respect to community size, however, we found the following relationship between perceived risk-communication capabilities and population size: perceived capabilities were highest in the large communities (≥50,000 population), followed by small communities (2,500–19,999), and lowest in medium-sized communities (20,000–49,999 population). The 95% confidence interval and ANOVA (p≤0.05) confirmed the pattern was unlikely to be attributable to chance. The results of this analysis support the need to factor population diversity into risk-communication plans as well as the need for improved state or regional risk-communication capabilities, especially for communities with limited local capacity.18

DISCUSSION

Nelson and colleagues define PHEP as the ability of “the public health and health care systems, communities, and individuals to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from health emergencies, particularly those whose scale, timing, or unpredictability threatens to overwhelm routine capabilities.”19 To be truly prepared, public health systems must be able to satisfactorily perform a number of different response capabilities such as surveillance, epidemiologic investigation, laboratory testing, disease prevention and mitigation, surge capacity for health-care services, risk communication to the public, and overall system response coordinated through effective incident management.

While a number of methods and instruments for measuring PHEP have been established, most of the current measures are designed to assess capacities (quantities of material assets and infrastructure elements). As experienced during the response to the 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes and 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreak, availability of physical and infrastructural resources is only one predictor of successful emergency response. More critical is the measurement of a public health system's capabilities (its collective ability to undertake functional or operational actions using available preparedness assets to function in a coordinated manner to effectively identify, characterize, respond to, and recover from an emergency). These capabilities can be categorized into domains aligned with the traditional core public health functions of assessment, policy development, and assurance,20 as well as the key functions of leadership, coordination, and communication.

There are several significant barriers to measuring PHEP capabilities. First, because large-scale public health emergencies are rare, opportunities to observe systematically or measure public health system responses in action are limited. Moreover, even when emergencies do occur, the complexity and limited advance warning make it difficult to evaluate response systematically.

Second, because of the heterogeneity of public health systems and the range of possible emergencies for which they must prepare, no one has yet defined the “gold standard” of an appropriate response or even definitively identified the necessary individual public health response elements. A truly effective response is multifactorial in that it relies on a wide range of capabilities and enlists the support of numerous partners outside formal public health agencies (e.g., health-care organizations, EMS, media, and law enforcement). With wide variations in the structure and function of city, county, regional, and state health departments, and with necessary reliance on partners outside public health to accomplish certain critical tasks such as risk communication and mass care, measuring the performance of a single individual or even agency without looking at the performance of the “system” as a whole is challenging. As a result, measuring and practicing systems-level capabilities is enormously complex, requiring knowledge of all elements that comprise the system and opportunities where all disciplines are brought together to function as a system.

Because real-world opportunities to practice and evaluate PHEP capabilities in action are limited, employing potential proxy events that capture the key elements of public health emergencies presents opportunities to educate personnel on disaster plans and procedures through hands-on practice, while offering constructive critiques of their actions. Moreover, the HSPH-CPHP experience shows that, with evaluation measures that are valid in context, exercises that simulate emergencies can be used to evaluate PHEP capabilities as well as to provide training and preparedness planning.

CONCLUSION

The HSPH-CPHP exercise program employs realistic PHEP exercise scenarios and rigorous evaluation methods to meet two aims: (1) educating the public health workforce on key public health system emergency preparedness issues, and (2) identifying specific systems-level challenges in the response to public health emergencies. Formal evaluation studies have demonstrated the usefulness of PHEP exercises in clarifying awareness of public health workers' roles and responsibilities, facilitating knowledge transfer among these individuals and organizations, and identifying specific public health systems-level challenges in PHEP.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work and commitment of their partners from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Central Maine Regional Resource Center, South Eastern Maine Regional Resource Center, Northern Maine Regional Resource Center, and the Maine Center for Public Health.

The authors also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Howard Koh for his leadership during his service as director of the Harvard School of Public Health Center for Public Health Preparedness (HSPH-CPHP) from 2004 through 2009. Dr. Koh currently serves as the Assistant Secretary of Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

The authors further acknowledge the faculty and staff members that have contributed to the work of the HSPH-CPHP exercise program during the past five years, including Bruce Auerbach, Jonathan Burstein, Rebecca Orfaly Cadigan, Paul Campbell, Catherine LaRaia, Michael Leyden, Gilbert A. Nick, Lindsay Tallon, and Marcia A. Testa.

Footnotes

This article was developed in collaboration with a number of partnering organizations, and with funding support awarded to the HSPH-CPHP under Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Grant/Cooperative Agreement #3U90TP124242-05S1 and #5P01TP000307-01 (Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Center). The content of this article and the views and discussions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any partner organizations, CDC, or HHS, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Public health preparedness: mobilizing state by state. A CDC report on the Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement. 2008. Feb, [cited 2010 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/publications/feb08phprep.

- 2.National Association of County and City Health Officials. 2008 national profile of local health departments. [cited 2010 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2008reports/index.cfm.

- 3.Biddinger PD, Cadigan RO, Auerbach BS, Burstein JL, Savoia E, Stoto MA, et al. On linkages: using exercises to identify systems-level preparedness challenges. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:96–101. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dausey DJ, Buehler JW, Lurie N. Designing and conducting tabletop exercises to assess public health preparedness for manmade and naturally occurring biological threats. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie N, Wasserman J, Stoto M, Myers S, Namkung P, Fielding J, Valdez RB. Local variation in public health preparedness: lessons from California. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.341. Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-341-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett DJ, Everly GS, Jr, Parker CL, Links JM. Applying educational gaming to public health workforce emergency preparedness. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:390–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chi CH, Chao WH, Chuang CC, Tsai MC, Tsai LM. Emergency medical technicians' disaster training by tabletop exercise. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:433–6. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.24467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henning KJ, Brennan PJ, Hoegg C, O'Rourke E, Dyer BD, Grace TL. Health system preparedness for bioterrorism: bringing the tabletop to the hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:146–55. doi: 10.1086/502366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livet M, Richter J, Ellison L, Dease B, McClure L, Feigley C, Richter DL. Emergency preparedness academy adds public health to readiness equation. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;(Suppl):S4–10. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quiram BJ, Carpender K, Pennel C. The Texas Training Initiative for Emergency Response (T-TIER): an effective learning strategy to prepare the broader audience of health professionals. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;(Suppl):S83–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter J, Livet M, Stewart J, Feigley CE, Scott G, Richter DL. Coastal terrorism: using tabletop discussions to enhance coastal community infrastructure through relationship building. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;(Suppl):S45–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Homeland Security (US) Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) Volume I: HSEEP overview and exercise program management. 2007. Feb, [cited 2010 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: https://hseep.dhs.gov/support/VolumeI.pdf.

- 13.Federal Emergency Management Agency (US) About the National Incident Management System (NIMS) [cited 2010 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.fema.gov/emergency/nims/AboutNIMS.shtm.

- 14.SPSS Inc. SPSS®: Version 16.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savoia E, Biddinger PD, Fox P, Levin DE, Stone L, Stoto MA. Impact of tabletop exercises on participants' knowledge of and confidence in legal authorities for infectious disease emergencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2009;3:104–10. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e3181a539bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Health Alert Network. [cited 2010 Jul 1]. Available from: URL: http://www2a.cdc.gov/han/Index.asp.

- 17.Savoia E, Testa MA, Biddinger PD, Cadigan RO, Koh H, Campbell P, et al. Assessing public health capabilities during emergency preparedness tabletop exercises: reliability and validity of a measurement tool. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:138–48. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savoia E, Stoto MA, Biddinger PD, Campbell P, Viswanath K, Koh H. Risk-communication capability for public health emergencies varies by community diversity. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson C, Lurie N, Wasserman J, Zakowski S. Conceptualizing and defining public health preparedness. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(Suppl 1):S9–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]