SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We examined the prevalence of dental care during pregnancy and reasons for lack of care.

Methods

Using a population-based survey of 21,732 postpartum women in California during 2002–2007, we calculated prevalence of dental problems,receipt of care, and reasons for non-receipt of care. We used logistic regression to estimate odds of non-receipt of care by maternal characteristics.

Results

Overall, 65% of women had no dental visit during pregnancy; 52% reported a dental problem prenatally, with 62% of those women not receiving care. After adjustment, factors associated with non-receipt of care included non-European American race/ethnicity, lack of a college degree, lack of private prenatal insurance, no first-trimester prenatal insurance coverage, lower income, language other than English spoken at home, and no usual source of pre-pregnancy medical care. The primary reason stated for non-receipt of dental care was lack of perceived need, followed by financial barriers.

Conclusions

Most pregnant women in this study received insufficient dental care. Odds were elevated not only among the poorest, least educated mothers,but also among those with moderate incomes or some college education.The need for dental care during pregnancy must be promoted widely among both the public and providers, and financial barriers to dental care should be addressed.

The published literature during the past decade has called attention to the importance of oral health during pregnancy, not only for potential risks for poor pregnancy outcomes, but also because untreated infections in the mouth can be painful and have adverse long-term health consequences for the woman and her child. Dental caries is a bacterial infection that is highly transmissible from mother to infant, and control of dental caries in pregnant women has the potential to reduce the severity of transmission once their babies are born.1 Furthermore, in part due to hormonal and immunologic changes, pregnant women are at high risk for pregnancy gingivitis (up to 75% of pregnancies)2—which can lead to periodontitis3—and pregnancy granuloma, an enlarged lump on the gum that can be painful, make eating difficult, and lead to complications from uncontrollable bleeding.2 Evidence also suggests that pregnancy exacerbates preexisting periodontal disease.4 Some observational studies have shown associations between periodontitis and a small-for-gestational-age birth5 or preterm birth;6–12 however, a causal connection has not been established because trials have not consistently shown reduction in preterm labor or delivery with periodontal treatment.13–16

The effects on preterm birth notwithstanding, periodontal disease during pregnancy has been associated with adverse maternal outcomes such as systemic inflammation,17 preeclampsia,18–20 and miscarriage.21 Moreover, adverse effects of periodontal infections on the systemic health of adults are well documented. Periodontitis has been linked to diabetes/glycemic control, pulmonary infections, and cardiovascular disease.22–24

Prenatal care is an opportune time for appropriate referrals from medical providers for oral health care, because women are more likely to pursue medical care during pregnancy than at other times, and the prevalence of gingivitis is high. Studies have indicated that providing oral health care to a pregnant woman is safe and effective.25–27 The American Academy of Periodontology recommends that “women who are pregnant or are planning pregnancy should undergo periodontal examinations. Appropriate preventive or therapeutic services, if indicated, should be provided.”28 The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry advises that “every expectant mother receive a comprehensive oral health evaluation from a dentist as early as possible during pregnancy.”29 An expert panel convened by the New York State Department of Health in 2006 to develop clinical practice guidelines for dental care during pregnancy stated that “oral health should be an integral part of prenatal care.”30 Similarly, the California Dental Association Foundation, in collaboration with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District IX, recently released guidelines for health professionals, which promote the importance and safety of dental care during pregnancy.31

Earlier studies have shown a deficit in the receipt of oral health care during pregnancy. Mangskau and Arrindell's study of births to women in North Dakota during 1995–1996 reported that 43% of women received oral health care during pregnancy. They found that older women with higher incomes and more education were the most likely to receive dental care. Not having any dental problems and financial barriers were the predominant reasons women did not seek care; however, these reasons were not examined by maternal characteristics.32 Work by Gaffield et al. described rates of oral health care in pregnancy from a population-based survey in four states (Arkansas, Illinois, Louisiana, and New Mexico), revealing very low levels of dental care during pregnancy overall (35%) during 1997–1998. Among women reporting dental problems in three states (Illinois, Louisiana, and New Mexico), only 45%–55% received care. Non-private prenatal insurance and late prenatal care initiation were significant predictors of lack of care in these three states; this study did not control for confounders.33

Lydon-Rochelle et al. examined data from a population-based survey of women in Washington State during 2000 and found that 42% received dental care during pregnancy. Lack of counseling on oral health care during pregnancy was the strongest predictor of lack of dental care; smoking and overweight/obesity were also associated with lack of care, but only among women with no reported dental problems. They did not account for insurance status nor describe reasons for lack of care.34 A study by Al Habashneh and colleagues of postpartum women in 2001–2002 indicated that only 49% reported visiting the dentist during pregnancy, and marital status, dental insurance, and dental habits and knowledge were independently related to use of care by these women. The study was limited to one county in Iowa and included predominantly white women of higher socioeconomic status.35 No studies were found that used data more recent than 2002.

In light of current professional interest in the need for oral health care during pregnancy, this study aimed to examine recent rates of dental care during pregnancy in a large, socioeconomically and racially/ethnically diverse population-based sample of women delivering in California, where one out of every seven U.S. births occurs.36 Additional aims were to describe the characteristics of women at highest risk of inadequate oral health care and to explore likely barriers to appropriate use of dental care for pregnant women overall and among subgroups.

METHODS

Data source

The Maternal Infant Health Assessment (MIHA) is an annual population-based survey of mothers delivering live infants in California during February through May of each year. MIHA is a collaborative effort of the California Department of Public Health, Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Program and researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, Department of Family and Community Medicine. The survey collects data on maternal demographic characteristics, health and health behaviors, and access to care, including oral health symptoms and access to oral health services.

A random sample of women who give birth during February through May is drawn from birth certificate data annually and stratified by race/ethnicity, maternal education, and region of residence. Self-administered surveys are mailed to sampled women approximately 10–14 weeks postpartum; a reminder and then a second survey are sent to nonresponders. Telephone follow-up is attempted for women who do not respond by mail. The unweighted response rates have been ≥70% each year. The final survey sample is linked back to birth certificate data and weighted to adjust for the stratified random sampling frame (based on birth certificate data on all California births) and, to the extent possible, for nonresponse bias. Demographic characteristics of MIHA respondents are similar to those of all women delivering a live birth in California (data available upon request). The sample for this study consisted of the 21,732 women who participated in the MIHA survey during 2002–2007, when oral health measures were available.

Study variables

This study focused on several variables:

Dental problem during pregnancy: A dental problem was recorded for women reporting having a toothache; a loose tooth; gums that bled “a lot” or that were painful, red, or swollen; cavities that needed to be filled; or a tooth that needed to be pulled.

Receipt of dental care during pregnancy: Women were asked if they ever visited a dentist or dental clinic during pregnancy. Responses were coded as yes or no.

Reasons for not receiving dental care during pregnancy: Women were asked to select the main reason they did not see a dentist during pregnancy. Responses were grouped into: financial barriers (no insurance or it cost too much); attitudinal barriers (she did not like going to the dentist, was too busy, or did not think about going); lack of perceived need; patient thought care unsafe (read or heard somewhere that she should not go during pregnancy); and provider advised against care (was told by a doctor, nurse, or someone in the dental office not to go). Due to differences in response categories in earlier years, reasons for not receiving care were only examined during 2004–2007 (n=8,558).

Based on the literature, the authors examined the following maternal characteristics obtained from birth certificate data linked with MIHA data:

Age: categorized as 15–19 years, 20–34 years, and ≥35 years.

Parity: including the index birth, categorized as first live birth, second to fourth live birth, or ≥fifth live birth, and collapsed into first birth vs. ≥second birth for logistic analyses.

Race/ethnicity/nativity: categorized into African American, Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander (API), European American, Latina (regardless of race), and other. Sufficient numbers allowed further categorization of API and Latina women by whether they were born in the United States.

Education: categorized as less than high school graduate/general equivalency diploma (GED), high school graduate/GED, some college, and college graduate or higher education.

Prenatal insurance payer by the end of pregnancy: grouped into Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid), private coverage, uninsured/self-pay, or other (CHAMPUS, Tri-Care, or other government programs) and examined as private vs. non-private/uninsured for logistic analyses.

We also examined the following characteristics measured only in MIHA data:

Timing of insurance coverage: categorized into coverage in the first trimester, or coverage after the first trimester/no coverage).

Family income: family income for the calendar year preceding the survey, adjusted for family size and grouped into 100% increments of the federal poverty level (FPL) as: ≤100% FPL (poor), 101%–200% FPL (near-poor), 201%–300% FPL, 301%–400% FPL, >400% FPL, or missing/unknown.

Marital status: status at delivery, classified either as married or unmarried; unmarried women included women who were separated, divorced, widowed, never married, or living with partners but not married.

Language usually spoken at home: English, Spanish, an Asian language, or another language, collapsed into English vs. non-English for logistic analyses.

Usual source of pre-pregnancy care: whether she had a doctor, nurse, or clinic she usually went to for medical care prior to pregnancy.

Pregnancy intention: whether she wanted to be pregnant at that time.

Any smoking during pregnancy: self-reported smoking during the first or third trimester of pregnancy.

Analysis

Using SAS®-callable SUDAAN®37,38 to account for sampling design, we calculated the proportions of women who reported having a dental problem during pregnancy and who reported receiving no dental care during pregnancy, overall and by maternal characteristics. We then conducted unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to determine which maternal characteristics were significantly related to lack of receipt of dental care among all women in the sample. Variables that were significant in the unadjusted analyses were included in the adjusted models. There were too few Native American women to include in any of the logistic regression analyses.

Finally, among those women interviewed during 2004–2007 who did not receive a dental visit during pregnancy, we examined the prevalence of reported reasons for not receiving dental care, overall and by maternal characteristics. We used Chi-square tests to examine the association between each characteristic and the reported reason for not receiving dental care.

RESULTS

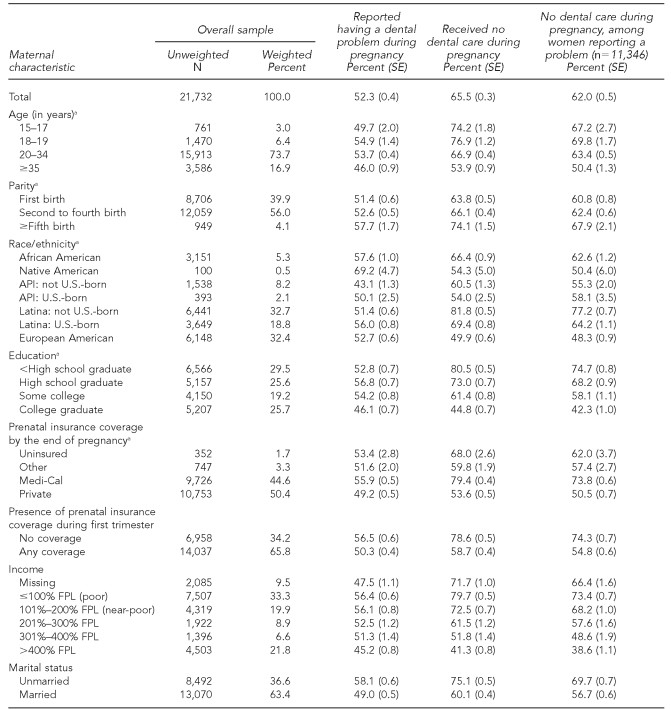

As shown in Table 1, the majority of women in the MIHA sample were aged 20 years or older and had experienced at least one birth prior to the index pregnancy. More than half of the sample was Latina, including 33% born outside of the U.S. and 19% U.S.-born; another third was European American. Almost 30% of the sample had not graduated from high school, while another 26% were college graduates. Nearly 45% of women had Medi-Cal for prenatal care, and 34% were uninsured during the first trimester of pregnancy. More than half were either poor (33%) or near-poor (20%). Thirty-seven percent of the sample was unmarried, 40% spoke a language other than English at home, 28% had no regular source of medical care prior to pregnancy, and 43% reported an unintended pregnancy. A relatively small percentage of women (9%) reported smoking at any point during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women and prevalence of dental problems and receipt of dental care, overall and by maternal characteristics, MIHA 2002–2007

aObtained from birth certificate data

MIHA = Maternal Infant Health Assessment

SE = standard error

API = Asian/Pacific Islander

FPL = federal poverty level

Of all women in the sample, half reported having a dental problem during pregnancy (Table 1); these were predominantly toothaches, painful or bleeding gums, or cavities that needed treatment. Native American women, unmarried women, women whose pregnancies were unintended, and women who reported smoking during pregnancy appeared to have the highest rates of dental problems. However, for the most part, the proportion of women reporting dental problems did not vary dramatically by maternal characteristics. Two-thirds of all women delivering in California reported receiving no dental care during pregnancy, and 62% of women reporting dental problems also did not receive care. Receipt of a dental visit appeared to vary greatly by maternal characteristics, overall and among women with a dental problem. While women who are typically considered disadvantaged (e.g., less educated, Medi-Cal-covered, low-income, or non-English-speaking) appeared to have the highest rates of lack of receipt of dental care, more than 40% of women with a college education or women in the highest income category also reported no dental care during pregnancy.

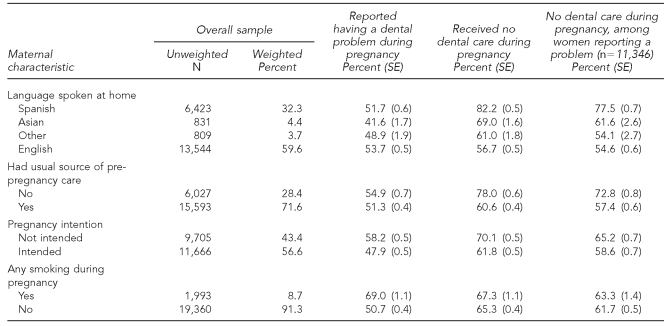

Table 2 displays the results of the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models predicting lack of receipt of dental care during pregnancy among all women in the study. The risks of not receiving dental care during pregnancy were higher among women in racial/ethnic minority groups, less educated and lower-income women, women who lacked first-trimester insurance coverage or a regular source of pre-pregnancy medical care, and women who did not speak English at home. Neither being unmarried nor having an unintended pregnancy was related to receipt of dental care in these analyses. For example, the odds ratios (ORs) for lack of dental care during pregnancy ranged from 1.13 (95% CI 0.91, 1.40) for U.S.-born API women to 1.66 (95% CI 1.45, 1.92) for non-U.S.-born Latinas relative to European American women. Compared with college-graduate women, women at every other education level—including those who had completed some college—had higher odds of not receiving dental care (ORs ranging from 1.32 [95% CI 1.19, 1.46] to 1.75 [95% CI 1.56, 1.95]). Similarly, women at every income level ≤400% FPL, including women with moderate incomes, had higher odds of not receiving dental care than higher-income women (ORs ranging from 1.27 [95% CI 1.11, 1.45] to 2.05 [95% CI 1.79, 2.35]. Lacking prenatal insurance coverage in the first trimester (OR=1.25 [95% CI 1.15, 1.36]) and lacking a regular source of pre-pregnancy medical care (OR=1.56 [95% CI 1.44, 1.70]) also were associated with lack of dental care during pregnancy, as was speaking a language other than English at home (OR=1.39 [95% CI 1.23, 1.56]).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for not receiving dental care during pregnancy, MIHA 2002–2007

abtained from birth certificate data

bStatistically significant

cNot included in final model

MIHA = Maternal Infant Health Assessment

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = referent group

API = Asian/Pacific Islander

FPL = federal poverty level

NA = not applicable

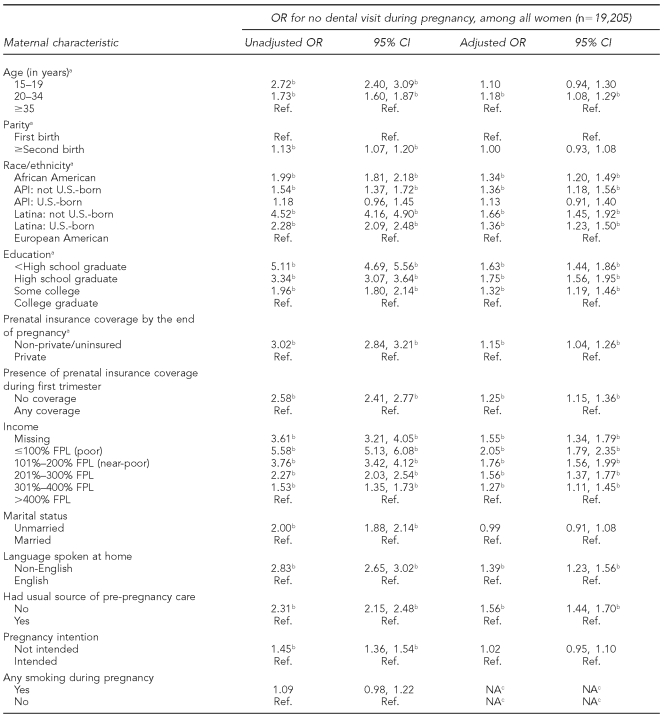

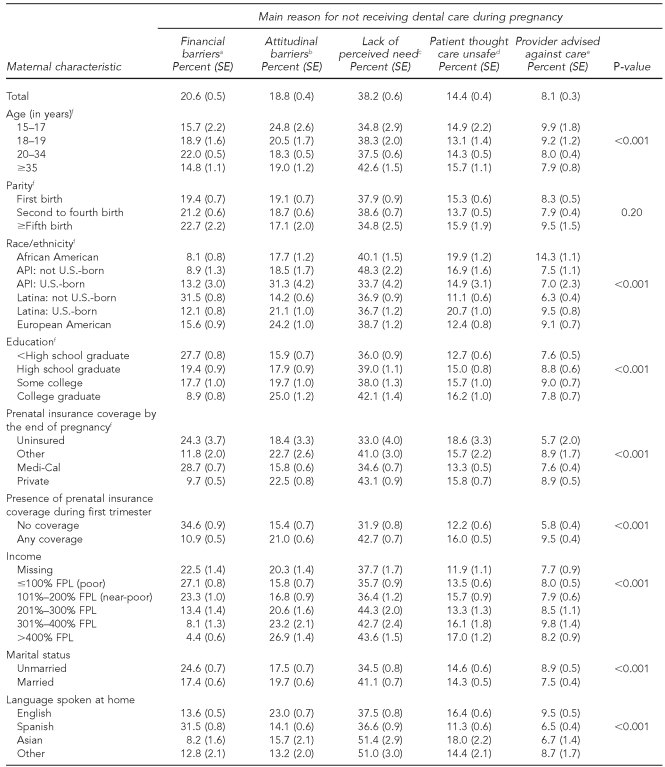

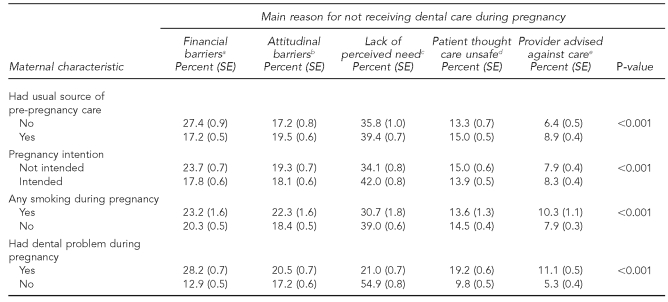

Table 3 depicts the main reasons women reported for not visiting a dentist or dental clinic during pregnancy, overall and among subgroups. The most common reason for not receiving a dental visit was not perceiving a need to go (38%), followed by financial barriers (21%), attitudinal barriers (19%), considering care unsafe (14%), and provider advising against care (8%). The reasons given for not receiving dental care varied significantly by most maternal characteristics, except number of live births. Younger teens appeared more likely than older women ≥35 years of age to indicate that they did not like going to the dentist, were too busy, or did not think of it (25% vs. 19%), while older women were somewhat more likely than younger women to indicate that they believed they did not need to go to the dentist during pregnancy (43% vs. 35%). Fourteen percent of African American women indicated that they did not get dental care during pregnancy because their medical or dental provider told them to wait until after pregnancy, compared with only 6%–10% of other racial/ethnic groups.

Table 3.

Reasons for not receiving dental care by characteristics of women not receiving dental care, MIHA 2004–2007 (n=8,558)

aNo dental insurance or it cost too much

bDidn't think of it, didn't like going to dentist, too busy

cDidn't need to go

dRead or heard somewhere it wasn't safe to go during pregnancy

eMedical or dental provider told her to wait until after pregnancy

fObtained from birth certificate data

MIHA = Maternal Infant Health Assessment

SE = standard error

API = Asian/Pacific Islander

FPL = federal poverty level

Financial barriers were cited most often by Latina women born outside of the U.S. (32% compared with 8%–16% of other groups). Compared with other racial/ethnic groups, U.S.-born API women were the most likely to indicate attitudinal barriers (31%); African Americans and U.S.-born Latinas appeared most likely to indicate that they read or heard somewhere that it was not safe to get dental care during pregnancy (20% and 21%, respectively). API women born outside of the U.S. and women who spoke an Asian or “other” language at home were more likely to indicate that they did not need dental care (48% and 51%, respectively) compared with other racial/ethnic or language groups (34%–40%). Higher rates of financial barriers to dental care were reported by more disadvantaged women (e.g., women who had not graduated from high school, were covered by Medi-Cal during pregnancy, had no prenatal coverage in the first trimester, were poor, were unmarried, or had no usual source of pre-pregnancy medical care) as compared with their counterparts. Women who were college graduates, privately insured, covered by insurance in the first trimester, high income, and married were somewhat more likely to report attitudinal barriers and lack of perceived need for care than more disadvantaged women. One-fifth (21%) of women who reported having a dental problem during pregnancy indicated that they believed they did not need to go to the dentist.

DISCUSSION

The large majority of pregnant women delivering in California, even those experiencing dental problems, did not have a dental visit during pregnancy. The results of this study should be of concern because of the implications for the oral and systemic health of women directly, as well as for the oral health of their children. While there are special considerations that dentists may need to make when delivering care to pregnant women, such as proper positioning in the dental chair or avoidance of aspirin-containing products and certain antibiotics such as tetracycline and erythromycin estolate, pregnancy itself should not preclude the provision of oral health care.26,27 Screening and referral for oral health problems should be a standard component of prenatal health care, and women should receive both preventive and therapeutic dental care during pregnancy, for health maintenance as well as disease control and prevention. Several states, such as New York and California, have developed guidelines for promoting and delivering oral health care during the perinatal period. Recent large, randomized clinical trials have demonstrated the safety of dental treatment during pregnancy, which should alleviate any concerns held by both providers and pregnant women previously.26

Our multivariate results highlighted the importance of both income and education in the receipt of dental care during pregnancy. Lower income and lower educational attainment were associated with approximately 1.5 to two times the risk of non-receipt of a dental visit, even after adjustment for each other and multiple sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics relevant to seeking health care, which could have been mediators and, therefore, would have reduced the observed odds for income and education. It is striking that, compared with women with the highest incomes, increased risks were observed not only for poor or near-poor women, but for women of all income levels up to 400% FPL. Similarly, risks were elevated not only among the least educated women, but among all educational groups compared with college graduates, including among women with some college education but no degree. Racial/ethnic disparities in receipt of dental care during pregnancy also were seen, with minority groups exhibiting 28% to 75% greater odds of not receiving a dental visit compared with European American women. Women in the income, educational, and racial/ethnic groups of elevated risk comprised approximately three-quarters of all women with live births in California during the study period.

The primary reason women reported for not receiving dental care during pregnancy was lack of perceived need. This barrier was prevalent among all groups, including college-educated, privately insured, high-income, married women, indicating that lack of awareness of the importance of dental care during pregnancy is widespread. One-fifth of African American and U.S.-born Latina women stated that they did not receive dental care because they had heard it was not safe during pregnancy. More than 14% of African American women reported that either a medical or dental provider told them to wait until after the pregnancy to obtain oral health-care services.

While the issues surrounding non-receipt of dental care during pregnancy are likely to be complex, our findings indicate that educational campaigns promoting the need for and safety of oral health care during pregnancy are necessary, while not sufficient, to improve receipt of care. These campaigns should target not only all pregnant women and the communities in which they live, but also prenatal and oral health providers. Recent studies demonstrating the safety and benefit of oral health care during pregnancy should encourage dental providers to accept pregnant patients. Obstetric or primary care providers, including nurses and midwives, also can play a key role in promoting and referring patients for oral health care during pregnancy.

Similar to Mangskau's findings in North Dakota,32 our study found that lack of insurance and/or cost of dental care was a significant reason for non-receipt of care, particularly among less educated, lower-income, Medi-Cal-covered, and/or unmarried women. These data suggest that financial barriers remain, despite expansions of dental coverage to low-income women. In 2005, California extended eligibility for preventive and emergency dental care to all pregnant women covered by Medi-Cal, with implementation required by 2008; however, more than one-quarter of women with Medi-Cal in our study cited financial barriers as their primary reason for not obtaining care, a proportion that did not vary much between 2004 and 2007 (data not shown). It will be important to continue to follow changes in receipt of dental care following the full implementation of that legislation, and to ensure that current benefits, which do not include needed restorative care, are sustained or expanded.

Furthermore, many women are only eligible for Medi-Cal while they are pregnant and for a short time thereafter and, thus, may only have dental coverage during that time. It is particularly important to try to deliver preventive and therapeutic oral health care to these women during their pregnancies, while they have coverage for care. At the same time, it is not enough only to provide oral health care during the prenatal period. Low-income women should have ongoing financial access to dental care, to promote good preconception and interconception oral health.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Because the survey combined the barriers “lack of dental insurance” and “it cost too much” in the same response category, we were unable to determine what proportion of our sample was uninsured for dental services. In addition, this study relied on self-reported use of dental care rather than review of dental records; however, adults' self-reports of use of care during the preceding year are widely used in health services research. Another limitation of this study was that it was restricted to California and its generalizability to other states is unknown; but given that one in seven U.S. births occurs in California, these findings have considerable national significance.36

CONCLUSIONS

Efforts are needed to widely promote the importance of dental care during pregnancy to all women and relevant providers, and to remove financial barriers to oral health care during pregnancy. To reduce disparities in receipt of dental care, targeted efforts must also be made to promote oral health care among women in lower-income, lower-education, and minority groups. As indicated in the 2003 Surgeon General's National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health, we must employ strategies at the “local, state, regional, and national levels” to elevate oral health to the same level of importance as general health, by changing perceptions of the public, policy makers, and health providers.39

The creation of clinical guidelines for the delivery of oral health care among pregnant women is a positive step in changing perceptions. Efforts also must be maintained to include oral health in national health-care reform considerations and implementation. Given the connections between oral health and overall health, and transmission from mother to infant of infectious bacteria responsible for early childhood caries, a stronger collaborative effort must be made between prenatal and dental providers as well as policy makers to ensure that all pregnant women receive the oral health care they need during their pregnancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Robert Isman, DDS, MPH, of the Medi-Cal Dental Services Branch of the California Department of Health Care Services for his insightful comments, and Michael Gorman, MD, for earlier work on this project. The authors also thank Shabbir Ahmad, DVM, MS, PhD, Acting Director of the Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Program (MCAH), Center for Family Health, California Department of Public Health; and Michael Curtis, PhD, Acting Chief, and Moreen Libet, PhD, of the Epidemiology, Assessment and Program Development Branch of MCAH, for their roles in developing and sustaining the Maternal Infant Health Assessment, and for their support for the oral health questions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkowitz RJ. Acquisition and transmission of mutans streptococci. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Dental Association Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations. Women's oral health issues. 2006. Nov, [cited 2010 Jun 7]. Available from: URL: http://www.ada.org/sections/professionalresources/pdfs/healthcare_womens.pdf.

- 3.Sheiham A. Is the chemical prevention of gingivitis necessary to prevent severe periodontitis? Periodontology 2000. 15:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laine MA. Effect of pregnancy on periodontal and dental health. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60:257–64. doi: 10.1080/00016350260248210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boggess KA, Beck JD, Murtha AP, Moss K, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease in early pregnancy and risk for a small-for-gestational-age infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1316–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez NJ, Da Silva I, Ipinza J, Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy reduces the rate of preterm low birth weight in women with pregnancy-associated gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 Suppl):2144–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobetsis YA, Barros SP, Offenbacher S. Exploring the relationship between periodontal disease and pregnancy complications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):7S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong X, Buekens P, Fraser WD, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. BJOG. 2006;113:135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson JE, II, Hansen WF, Novak KF, Novak MJ. Should we treat periodontal disease during gestation to improve pregnancy outcomes? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:454–67. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31804c9f05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vergnes JN, Sixou M. Preterm low birth weight and maternal periodontal status: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agueda A, Ramon JM, Manau C, Guerrero A, Echeverria JJ. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Hodgkins PM, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: results of a pilot intervention study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michalowicz BS, Hodges JS, DiAngelis AJ, Lupo VR, Novak MJ, Ferguson JE, et al. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1885–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novak MJ, Novak KF, Hodges JS, Kirakodu S, Govindaswami M, Diangelis AJ, et al. Periodontal bacterial profiles in pregnant women: response to treatment and associations with birth outcomes in the obstetrics and periodontal therapy (OPT) study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1870–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Jared HL, Mauriello SM, Mendoza LC, Couper DJ, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy on rate of preterm delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:551–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b1341f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton AL, Boggess KA, Moss KL, Jared HL, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease early in pregnancy is associated with maternal systemic inflammation among African American women. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1127–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boggess KA, Lieff S, Murtha AP, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conde-Agudelo A, Villar J, Lindheimer M. Maternal infection and risk of preeclampsia: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruma M, Boggess K, Moss K, Jared H, Murtha A, Beck J, et al. Maternal periodontal disease, systemic inflammation, and risk for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:389. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore S, Ide M, Coward PY, Randhawa M, Borkowska E, Baylis R, et al. A prospective study to investigate the relationship between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcome. Br Dent J. 2004;197:251–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin LJ, Chiu GK, Corbet EF. Are periodontal diseases risk factors for certain systemic disorders—what matters to medical practitioners? Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health and Human Services (US). Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): HHS,National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (US); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diaz-Romero RM, Casanova-Roman G, Beltran-Zuniga M, Belmont-Padilla J, Mendez JD, Avila-Rosas H. Oral infections and glycemic control in pregnant type 2 diabetics. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offenbacher S, Lin D, Strauss R, McKaig R, Irving J, Barros SP, et al. Effects of periodontal therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters, and pregnancy outcomes: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2011–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michalowicz BS, DiAngelis AJ, Novak MJ, Buchanan W, Papapanou PN, Mitchell DA, et al. Examining the safety of dental treatment in pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:685–95. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giglio JA, Lanni SM, Laskin DM, Giglio NW. Oral health care for the pregnant patient. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Task Force on Periodontal Treatment of Pregnant Women, American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology statement regarding periodontal management of the pregnant patient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:495. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar J, Samelson R, editors. Oral health care during pregnancy and early childhood: practice guidelines. Albany (NY): New York State Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on perinatal oral health care. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.California Dental Association Foundation. Oral health during pregnancy and early childhood: evidence-based guidelines for health professionals. Sacramento (CA): California Dental Association Foundation; 2010. [cited 2010 Feb 19]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdafoundation.org/library/docs/poh_guidelines.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangskau KA, Arrindell B. Pregnancy and oral health: utilization of the oral health care system by pregnant women in North Dakota. Northwest Dent. 1996;75:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaffield ML, Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: an analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1009–16. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Krakowiak P, Hujoel PP, Peters RM. Dental care use and self-reported dental problems in relation to pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:765–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Habashneh R, Guthmiller JM, Levy S, Johnson GK, Squier C, Dawson DV, et al. Factors related to utilization of dental services during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:815–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009 Mar 18;57:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Research Triangle Institute,Inc. SUDAAN®: Version 9.0.1. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.SAS Institute,Inc. SAS®: Version 9.2. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Department of Health and Human Services (US). National call to action to promote oral health. Rockville (MD): HHS, Public Health Service, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research,National Institutes of Health (US); 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]