Abstract

Currently, despite well-known mutational causes, a universal treatment for neuromuscular disorders is still lacking, and current therapeutic efforts are mainly restricted to symptomatic treatments. In the present study, δ-sarcoglycan–null dystrophic hamsters were fed a diet enriched in flaxseed-derived ω3 α-linolenic fatty acid from weaning until death. α-linolenic fatty acid precluded the dystrophic degeneration of muscle morphology and function. In fact, in dystrophic animals fed flaxseed-derived α-linolenic fatty acid, the histological appearance of the muscular tissue was improved, the proliferation of interstitial cells was decreased, and the myogenic differentiation originated new myocytes to repair the injured muscle. In addition, muscle myofibers were larger and cell membrane integrity was preserved, as witnessed by the correct localization of α-, β-, and γ-sarcoglycans and α-dystroglycan. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic accumulation of both β-catenin and caveolin-3 was abolished in dystrophic hamster muscle fed α-linolenic fatty acid versus control animals fed standard diet, while α-myosin heavy chain was expressed at nearly physiological levels. These findings, obtained by dietary intervention only, introduce a novel concept that provides evidence that the modulation of the plasmalemma lipid profile could represent an efficacious strategy to ameliorate human muscular dystrophy.

Human neuromuscular disorders are a heterogeneous group of genetic diseases caused by mutations determining structure alterations and function impairment in proteins of the cytoskeleton-extracellular matrix system with subsequent progressive loss of motor ability. Among others, mutations of genes coding for proteins of the sarcolemmal dystroglycan-sarcoglycan complex are responsible for a series of muscular disorders known as limb–girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs). In human beings, several subtypes of LGMDs have been identified and are characterized by wide genetic, molecular, and clinical heterogeneity. The process of gene identification in LGMDs has involved a combination of linkage and candidate gene analysis, resulting in a gene- and protein-based classification, which includes three known genes causing autosomal dominant LGMDs and 14 known genes causing autosomal recessive LGMDs. Among these mutated genes, sarcoglycans, a family of transmembrane dystrophin-associated proteins connecting myocyte cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix, are responsible for some subtypes of LGMDs,1 named sarcoglycanopathies. The expression of sarcoglycans can be secondarily reduced also in the presence of dystrophin mutations (Duchenne muscular dystrophy), indicating that the dystrophic muscles suffer from the combined deficiencies of dystrophin and sarcoglycans.2 However, despite the possibility of identifying causative mutations, dystrophic diseases are rare and so far very few controlled clinical trials have been carried out limiting the identification of the pathogenic mechanisms and of possible innovative treatments to experimental animal models, only.3 Indeed, owing to the multiplicity of mutated proteins involved, no universal treatment can be envisioned for dystrophic diseases, and an effective therapy is still lacking. In this context, protocols based on different drugs, genes, and cells have been proposed to counteract muscle derangement,2,3,4 and nutritional supplements have been considered in the attempt to increase muscle strength and prevent myocyte catabolism5,6,7 or to decrease corticosteroid side effects.8

ω3 and ω6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are metabolically and functionally distinct and often have opposing physiological effects. Mammals depend on dietary intake of ω3 fatty acids through vegetable sources or fish oil because their cells lack enzymes necessary to synthesize the 18-C precursor of ω3 fatty acids and to introduce a double bond at the ω3 and ω6 position. PUFAs exhibit positive effects on many experimental biological systems and induce substantial amelioration in different human diseases9,10,11 by altering lipid composition12 and plasma membrane structure to regulate intracellular signaling9,10,11,12 and metabolism.

The present study has been designed to test the hypothesis that ω3 PUFAs could alleviate the dystrophic skeletal muscle damage differently modulating the myocyte membrane composition and conformation and, hence, the intracellular signaling.10,11,13,14,15,16,17 The study has been conducted by administering ω3 α-linolenic acid (ALA) to dystrophic hamsters taking into consideration the capability of this experimental animal model to uptake, transport, and store this specific PUFA.18 In particular, the investigation has been performed in UM-X7.1 hamsters, because this strain reproduces very closely the human LGMD2F phenotype. The UM-X7.1 hamster carries the deletion of the δ-sarcoglycan (δ-SG) gene, resulting in a deficient δ-SG transcript and consequent loss of the protein from muscle membrane in combination with the reduced expression of α-, β-, and γ-SG.19,20 The ablation of the δ-SG, a structural glycoprotein of skeletal and cardiac muscle cell membranes,21 induces a widespread perturbation of cell/cell and cell/extracellular matrix (ECM) contacts, detachment of the basal membrane, and aberrant intracellular signaling pattern.20,21,22,23,24

The present investigation has shown that an ALA-enriched diet i) precludes myocyte and muscular tissue damage in δ-SG-null dystrophic hamsters, and ii) modulates satellite cells proliferation promoting myogenic differentiation. The skeletal muscle damage, similarly to hereditary cardiomyopathy,13,20,21,22,23,24 is prevented by modifying plasmalemma biophysical properties and membrane signaling to the intracellular compartment.14,25

Materials and Methods

Dietary Treatment

Dystrophic hamsters affected by a deletion in the δ-SG gene (strain UM-X7.1 Syrian hamster) were used. Two groups (50 animals each) of dystrophic hamsters were studied: the first group (pellet) was fed a standard pellet chow diet (Rieper, Bolzano, Italy), and the second (ALA) an ALA-enriched diet (flaxseeds, apples, and carrots). All animals were allowed to consume each diet component ad libitum from weaning to death. A third group of UM-X7.1 hamsters (30 animals) was fed the standard pellet chow from weaning to the age of 100 days, then fed for 50 days the ALA-enriched diet, and immediately sacrificed. In the ALA diet, fresh fruits and vegetables supplied carbohydrates and vitamins, while flaxseeds were the only source of fats, with ALA representing 52% of total lipids.24 The diet composition analysis indicated that all macro- and micronutrients needed for animal health maintenance were in due proportion in both dietary regimens. In 100 g of pellet chow or ALA diet, the caloric power was 222.5 and 202.8 kcal, respectively. However, every 7 days, animal weights were recorded to exclude possible decrements due to calorie restriction.24 A group of Golden Syrian hamsters (30 animals) was fed standard pellet chow only and used as healthy control.

Harvesting of Muscle Tissue and Cross-Sectional Area Measurements

Animals were anesthetized with urethane (400 mg/kg ip) and sacrificed. Muscles extensor digitorum longus (EDL), adductor, diaphragm, and gastrocnemious were rapidly excised, washed in cold 1× PBS, pH 7.4, weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Alternatively, muscle were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for light microscopy. Fiber cross-sectional areas (CSA) were measured with a Leica DMRB microscope (Wetzlar, Germany); five hundred fibers from random fields per animal were analyzed, (n = 5 animals per group; objective: ×20 equipped with a digital camera). All animal handling procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institute of Health and were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Skeletal and Plasma Fatty Acid Composition

To analyze fatty acid composition, plasma and EDL muscle samples were obtained from seven animals per group. Muscle tissues were homogenized and lipids were extracted from aliquots of plasma or tissue homogenates according to Folch’s method, as previously described.24

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies used for immunofluorescence were as follows: anti–α-MHC, mouse Mab (1:3000), clone BA-G5 from Stefano Schiaffino; anti–α-SG, mouse Mab (1:200), clone βSarc/5B1; anti–β-SG, mouse Mab (1:200), clone Ad1/20A6; anti–γ-SG, mouse Mab (1:200), clone 35DAG/21B5; anti–δ-SG, mouse Mab (1:200), clone δSarc3/12C1 all from Novocastra (Newcastle on Tyne, UK); anti–α-dystroglycan (α-DG), goat Mab (1:200), sc-46052 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and rhodamine phalloidin (1:500), R-415 FITC-labeled antibody (1:300) was from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA). Antibodies used for immunostaining were as follows: anti–β-catenin, mouse Mab (1:200), sc-7963, and anti–caveolin-3, mouse Mab (1:200), cat no. 610420 from BD Transduction (San Jose, CA); anti-telomerase (TERT), rabbit (1:200), sc-7212 from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; peroxidase immunostaining from Vector Laboratories Inc. (Burlingame, CA); anti-CD45, mouse Mab (1:100), cat n. 550286 from BD Transduction; anti–Pax 3–7, goat Mab (1:100), sc-7749 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-myogenin, mouse Mab (1:200), cat no. 556358 from BD Transduction; anti-desmin, rabbit Mab (1:200), cat no. ab8592 from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); alkaline phosphatase immunostaining was from Histo-line Laboratories (Milan, Italy); peroxidase immunostaining from Vector Laboratories Inc. (Burlingame, CA).

Western and Northern Blot Analyses and TUNEL Assay

Myofibrillar extracts were prepared using the Caforio’s procedure, as previously described.24 Specific antibodies were as follows: anti–α-MHC, (1:5000) mouse Mab, clone BA-G5; anti-total MHC, except Myosin IIx, (1:3000) mouse Mab, clone BF-35 from Stefano Schiaffino; anti–β-MHC (1:4000), mouse Mab, clone NOQ7.5.4D from Abcam; anti-MLC1 (1:200), mouse Mab, and anti-MLC2 (1:200), rabbit Mab, from Huda Shubeita. To perform Western blot analysis for α-DG and α-, β-, γ-SG, EDL tissues were homogenized in a buffer solution containing 320 mmol/L sucrose, 100 μmol/L Na2EDTA, 100 μmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The antibodies for α-DG and α-, β-, γ-SG have been already mentioned in the immunofluorescence section. Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-linked (Vector Laboratories Inc.) and revealed by ECL (GE Healthcare, Milan, Italy). Western blot bands were quantified by the DS Software (Rome, Italy). Northern blot analysis of α-SG and α-, β-, γ-SG was performed as previously described26; cDNA probes were a kind gift of Aiji Sakamoto. TUNEL assay was performed on paraffin sections using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Monza, Italy). The number of TUNEL- and TERT-positive nuclei was determined in random selected fields with a Leica DMRB microscope (Wetzlar, Germany); objective ×40 equipped with a digital camera. For each group, 30 fields per animal covering a total area of 5 mm2 were observed.

Statistical Analysis

Results are represented as mean ± SD. α-level was considered 0.05. For comparisons among more than two groups, analysis of variance was performed, while for comparisons between mean differences of two groups, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used. For frequencies, χ2 Pearson test and Kruskal Wallis test were used (SPSS for Windows, version 11.5; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Preservation of the Skeletal Muscle Morphology in Dystrophic Hamsters

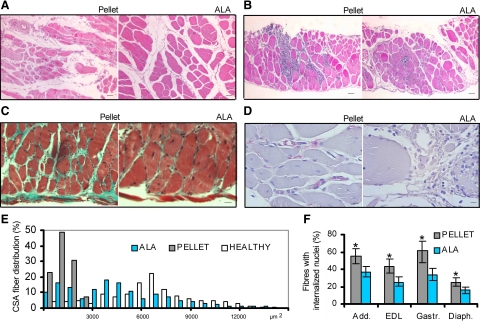

The gross histological analysis of gastrocnemious (Figure 1A), diaphragm (Figure 1B), EDL, and adductor muscles from dystrophic hamsters fed ALA-enriched versus pellet diet revealed an extensive preservation of the typical histological muscle features, as shown by a stronger and more homogeneous H&E staining. Furthermore, an increased size of myofibers, which were poligonal rather than rounded in shape, was found from the age of 30 days throughout the entire lifetime. In addition, in 150-day-old ALA-fed hamster muscles, the fibrotic tissue was not detectable by Masson trichrome staining (Figure 1C), while CD45 positive cells were extremely rare (Figure 1D). By contrast, in diaphragm, adductor, and EDL muscles of age-matched pellet dystrophic hamsters, the accumulation of interstitial fibrosis (Figure 1C) and the presence of CD45-positive cells (Figure 1D) were detectable and stable in all samples considered. The evidence that ALA muscular texture was qualitatively improved has been confirmed by other markers. The mean fiber CSA of the adductor muscle (Figure 1E) was larger (4855.2 ± 1536.3 versus 1890.2 ± 821.5) in 150-day-old ALA group in respect to age-matched pellet hamsters; as reference, the mean fiber CSA of the adductor muscle in healthy controls was 7510.3 ± 3454.9 (μm2 ± SD, P < 0.001, Kruskal Wallis test: χ2 = 123.98; df = 2). In addition, like in healthy animals, the CSA frequency distribution in ALA-fed hamster muscles was shifted to indicate the presence of medium-sized fibers, whereas it was low-sized in pellet-fed hamsters. Consistently, the wet weight of the gastrocnemious muscle, assumed as representative of the overall muscle condition, was significantly higher (approx. +25%) in ALA versus age-matched pellet hamsters. Finally, the frequency of fibers with internalized nuclei was decreased in all muscles of ALA hamsters analyzed (Figure 1F), while they were randomly distributed and frequent in pellet muscles (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

ALA precludes muscle morphology subversion in dystrophic hamsters. A: Gastrocnemius muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamster. H&E; Scale bars = 500 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. B: Diaphragm of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamster. H&E; Scale bar = 500 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. C: Diaphragm of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamsters. Masson-trichrome; Scale bars = 250 μm; n = 10 hamsters per group. D: EDL muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamster. CD45 immunohistochemical staining; Scale bars = 50 μm; n = 10 hamsters per group. E: CSA percent distribution in the adductor muscle. ALA, flaxseed-fed dystrophic hamsters; Pellet, pellet-fed dystrophic hamsters; Healthy, pellet-fed healthy hamsters. Representatively, a total of 500 fibers from all hamster groups have been considered as 100%. n = 5 hamsters per group. F: Percentage of fibers displaying internalized nuclei in the adductor, EDL, gastrocnemius, and diaphragm muscles of dystrophic hamsters fed pellet (gray) and ALA (pale blue); Mean ± SD; n = 7 hamsters per group: *P < 0.01 ALA versus pellet. All sections were from 150-day-old hamsters. Details are reported in the Materials and Methods.

Satellite Cells Proliferation and Myogenic Differentiation

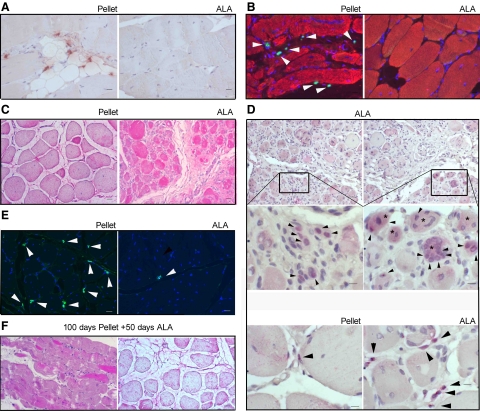

The preservation of quasi-healthy morphological characteristics in ALA-fed hamster muscles suggested verifying the muscle degeneration/regeneration balance through the assessment of the apoptotic nuclei and TERT staining and content. In the adductor, EDL and diaphragm muscles of all animal groups considered, TERT-positive nuclei were mostly lying between the sarcolemma and the basal lamina (Figure 2A) and only 1% were under the sarcolemma without difference in the location of TERT-positive nuclei. However, a significantly higher number of cells expressing TERT (18.86 ± 5.37 versus 6.95 ± 3.2; P < 0.0001, Mean ± SD/5 mm2) and apoptotic figures (25.65 ± 7.7 versus 9.27 ± 4.27 , P < 0.0001 - Mean ± SD/5 mm2), as assessed by TUNEL assay, was neighboring the areas of muscular damage of pellet- versus ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters (Figure 2B). Notably, the reduced expression of TERT in ALA dystrophic muscles diverged from the expression of the markers of myogenesis. In fact, in ALA hamster muscles, desmin displayed a strong expression (Figure 2C) that was not confined in a fiber subpopulation with specific CSA (Figure 2C), while it was almost absent in muscle fibers of pellet hamsters. Consistently, satellite cells expressing Pax 7 were markedly reduced in ALA versus pellet-treated dystrophic hamsters (Figure 2E). To confirm that cell differentiation was actively progressing in the satellite cells, myogenin expression was investigated. In ALA versus pellet hamster muscles, myogenin was highly expressed (Figure 2D) and myogenin-positive myoblasts with single or multiple nuclei were detected among fibers, independently of their CSA. A faint myogenin-specific signal was also detectable in the cytoplasm, besides nuclei, of a few scattered fibers.

Figure 2.

ALA promotes dystrophic hamster muscle proliferation and differentiation. A: EDL muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamsters. TERT nuclear immunohistochemical staining; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. B: Adductor muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamsters. DAPI (blue) and TUNEL (green, white arrowheads) nuclear staining. Actin staining (red) evidences the cytoplasm; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. C: EDL muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamsters. Desmin immunohistochemical staining; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. D: EDL muscle of pellet and ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters. Myogenin immunohistochemical staining. Upper panel: ALA-fed muscle; Scale bars = 200 μm; magnification (middle): Scale bars = 500 μm. Lower panel: Pellet- and ALA-fed muscle; Scale bars = 500 μm. Black arrowheads show myogenin positive nuclei, while asterisks mark cytoplasmic myoblast myogenin staining. E: EDL muscle of pellet- (left) and ALA-fed (right) dystrophic hamsters. Pax 7 immunofluorescence (white arrowheads); Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters per group. F: EDL muscle of dystrophic hamsters aged 150 days (100 days pellet + 50 days ALA). H&E staining (left) and desmin immunohistochemical staining (right) of left; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters. For details, see the Materials and Methods.

To verify whether, in dystrophic muscles, ALA could only prevent the damage or, to some extent, also revert the well-established injury, a group of dystrophic hamsters were fed standard pellet chow from weaning to the age of 100 days, when the muscle damage and fibrosis were already consolidated, and then fed ALA-enriched diet for 50 days. In all of the dystrophic animals investigated, no significant beneficial effects were observed after ALA administration (Figure 2F).

Precluding Sarcolemma and Intracellular Signaling Perturbation in Dystrophic Hamsters

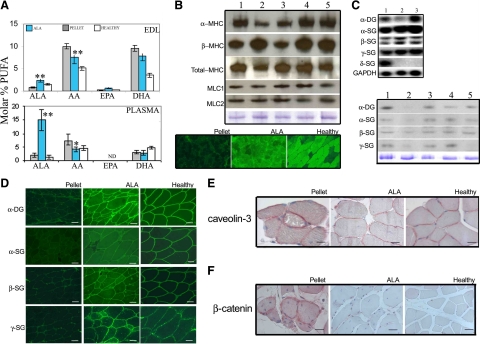

The beneficial effects exerted by ALA at morphological level in dystrophic muscles were supported by the preservation of the biochemical and molecular myocyte features. In fact, in flaxseed-fed hamster EDL muscles, ALA and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 ω3) molar percentage were up to 2- and 2.6-fold higher in respect to controls, respectively. Conversely, arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 ω6) molar percentage was decreased (−25%). Finally, in ALA dystrophic muscles, the EPA/AA ratio was 3.5 fold increased. Lastly, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 ω3) molar percentage decreased (−20%) in EDL tissue after ALA treatment (Figure 3A). The fatty acids composition of the plasmalemma of ALA-fed hamsters was not dissimilar to healthy controls.

Figure 3.

ALA preserves plasmalemma integrity and MHC isoforms ratio. A: PUFAs molar percent in EDL muscles and plasma of ALA- (blue bars) and pellet-fed (gray bars) dystrophic hamsters, and healthy hamsters fed pellet. ALA, α-linolenic acid (18:3, ω3); AA, arachidonic acid (20:4, ω6); EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, ω3), DHA, docosahexaenoic acid (22:6, ω3). Bars express the mean ± SD of 7 hamsters/group; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 ALA- versus pellet-fed dystrophic hamsters; analysis of variance and two tails t-test for means. Β: Representative Western blot analysis of α-, β-, total-MHC, MLC1, and MLC2 from EDL muscles of healthy hamsters fed pellet (lanes 1 and 4), dystrophic hamsters fed pellet diet (lane 2), and dystrophic hamsters fed ALA diet (lanes 3 and 5) at 150 (lanes 1 thru 3) and 420 (lanes 4 thru 5) days of age. MHC, myosin heavy chain, MCL, myosin light chain. Bottom: α-MHC expression pattern, as detected by immunofluorescence, in EDL muscles of 150-day-old pellet-, ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters and healthy controls. C: Representative Northern blot analysis of α-DG and α-, β-, γ-, δ-SGs from EDL muscles of healthy hamsters fed pellet diet (lane 1), dystrophic hamsters fed pellet diet (lane 2), and dystrophic hamsters fed ALA diet (lane 3). Bottom: Representative Western blot analysis of α-DG and α-, β-, γ-SGs from EDL muscle of healthy controls fed pellet diet (lane 1 and 4), dystrophic hamsters fed pellet diet (lane 2), and dystrophic hamsters fed ALA diet (lane 3 and 5) at 150 (lanes 1 thru 3) and 420 (lanes 4 thru 5) days of age with Coomassie staining. D: α-DG and α-, β-, γ-SGs expression pattern, as detected by immunofluorescence, in the adductor muscle of pellet- and ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters and healthy controls. Scale bars = 50 μm, n = 7 hamsters aged 150 days per group. E: Adductor muscles of pellet- and ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters, and healthy controls. Caveolin-3 immunohistochemical staining; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters aged 150 days per group. F: Adductor muscles of pellet- and ALA-fed dystrophic hamsters, and healthy controls. Caveolin-3 and β-catenin immunohistochemical staining; Scale bars = 100 μm; n = 6 hamsters aged 150 days per group. α-DG, α-dystroglycan; SG, sarcoglycan. For details, see the Materials and Methods.

In dystrophic muscles, mutations in the dystrophin-sarcoglycan complex determine plasmamembrane instability and subsequent perturbations in signaling cascades.13,17,20,21,22,23,24 The modifications in plasmalemma composition as well as the preservation of the morphological features and the activation of the myogenic cascade suggested investigating whether ALA administration could also preserve the expression pattern of some among the major myocyte protein systems. Western blot analysis showed that, among others, the α-MHC expression was increased up to threefold, while β-MHC was reduced in ALA versus pellet muscle extracts (Figure 3B). Therefore, ALA contributed to preserve a more physiological α/β MHC ratio in skeletal muscle increasing the number of α-MHC-positive myofibers, as observed by immunofluorescence (Figure 3B), approximating healthy controls (12 versus 90 versus 70 fibers/250 mm2; test χ2 P < 0,0001). Myosin light chain isoforms were also assessed by Western blot analysis in EDL muscle extracts, but they were not affected by ALA treatment at any age considered (Figure 3B).

In pellet versus ALA muscles, the expression level of α-, β-, γ-SG genes, as detected by Northern blot analysis, was similar (Figure 3C); only the α-DG signal was slightly higher in ALA EDL extracts. Conversely, a severe reduction in the α-DG and α-, β-, γ-SG signal (Figure 3, C and D) was shown by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence in EDL of pellet dystrophic hamsters, while, in ALA EDL myocytes, the α-DG and α-SG pattern was slightly similar to healthy controls of the same age.

Concerning other membrane proteins, caveolin-3, involved in cell adhesion and membrane repair,27,28 and β-catenin, involved in maintaining plasma membrane integrity,29,30 although present on the sarcolemma, displayed a remarkable cytoplasmic accumulation in pellet hamster muscles (Figure 3, E and F). Conversely, in ALA-treated dystrophic hamster muscles, no detectable cytoplasmic accumulation of caveolin-3 (Figure 3E) and β-catenin (Figure 3E) was found and their sarcolemmal localization was undistinguishable in respect to healthy controls. Furthermore, in dystrophic muscles, ALA treatment preserved the sarcolemmal pattern of α-, β-, γ-SGs, α-DG, caveolin-3, and β-catenin, drastically modified in pellet dystrophic muscles.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that long chain ω3 ALA, modulating the sarcolemma lipid composition and protein pattern, precludes the aberrant signaling generated by mutations in genes encoding for myocyte cytoskeletal proteins and preserves suitable morpho-functional features in dystrophic skeletal muscles. The preserved integrity of the skeletal and myocardial24 muscle structure by ALA dramatically ameliorated the quality of muscular functional structures so impressively extending the dystrophic hamster longevity.

Three major factors concur to determine such conspicuous ALA effects: i) the modulation of the lipid membrane composition and configuration with the preservation of the expression and location of key-role signaling proteins, such as β-catenin, caveolin-3, SGs, and DG; ii) the slowing down of the myocyte degeneration/regeneration cycling rate associated with the enhancement of the myogenic differentiation typically observed in muscular dystrophy2,4,31 and iii) the ALA administration timing.

Dystrophic degeneration is caused by plasmamembrane fragility and consequent perturbation of the intracellular signaling,13,19,20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30 as also witnessed by caveolin-3 and β-catenin displacement within skeletal myocytes. The derangement of the membrane lipid organization in dystrophic muscles has been widely described in hamsters24,32 and in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy mouse model by MALDI-MS profiling that revealed a different lipid ratio in destructured versus normal areas of leg muscle sections.33 ALA administration induced a remarkable modification in the lipid pattern of dystrophic skeletal muscles. In flaxseed-fed dystrophic hamster muscles, ALA content and EPA/AA ratio were increased, while DHA content was decreased, similarly to myocardium.14,24 Changes in lipid composition influence membrane function by regulating protein and lipid membrane homeostasis.12,13,14,17,25,34 Although biophysical or chemical interactions between PUFAs, either as constituents of membrane phospholipids or free molecules, and membrane proteins or lipids have not been studied yet in the same model, they contribute to determine cell membrane chemo-physical features, including membrane organization, ion permeability, elasticity, and microdomain formation. In particular, ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids increase bilayer propensity to be in a liquid-disordered phase, decrease membrane thickness,25,33,34 and modulate proton membrane permeability and leaflet thickness enhancing fatty acids’ flip-flop rate.14 In patients treated with the “membrane lipid therapy” (ie, in which the membrane cell function has been nutritionally manipulated modifying the membrane lipid composition),14,15,25 the raft/non-raft localization and, hence, the function of several proteins involved in cell signaling were significantly modified.10 In fact, the ALA-induced preservation of plasmalemma composition and structure beneficially influences the expression pattern of membrane signaling proteins,21 such as α-, β-, γ-SGs, and α-DG. Notably, in vivo evidences in human beings35 indicate that α-, β-, and γ-SG glycoproteins can be maintained and expressed in the sarcolemma despite the absence of the δ-SG protein caused by its gene deletion and that the partial retention of the sarcoglycan complex might account for the milder clinical course of the disease. In addition, the aberrant accumulation of caveolin-3 and β-catenin in the cytoplasm of dystrophic muscles is completely inhibited by ALA administration implying that also the related signaling cascades are regularly operated, as indirectly demonstrated by the expression pattern of the MHC isoforms in ALA-dystrophic muscles. In pellet-fed dystrophic hamsters, α-MHC decreases and β-MHC increases paralleling the muscle damage severity. Conversely, ALA administration is associated with a quasi-physiological α/β MHC ratio in dystrophic hamsters, mainly contributed by the preservation of elevated α-MHC levels, as highlighted by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence. These findings are similar to those previously observed in the ventricular tissue24 implying that ALA diet exerts analogous beneficial effects on all striated muscles (myocardium, diaphragm, and skeletal muscles) of the dystrophic hamsters. The safeguard of the myocyte biochemical pattern entails that the fiber size in ALA-treated gastrocnemious, EDL, adductor and diaphragm muscles is greater than in pellet-fed dystrophic animals and CSA is occasionally even larger than healthy controls of the same age. In ALA-fed dystrophic adductor muscle, the mean CSA is twice bigger than pellet-fed dystrophic controls. However, a broad variability was observed in CSA of ALA versus pellet muscles, showing a nonhomogenous tissue attitude. In addition, fibers showing internalized nuclei were decreased in ALA versus pellet hamster muscles. Taken together, muscles from ALA- versus pellet-fed hamsters display a larger “myonuclear domain” (ie, the theoretical myocyte volume associated with a single nucleus).36,37 Because it is highly dependent on muscle fiber type, independently of species, the increased myonuclear domain could be in close relationship with the notable increase in α-MHC observed in ALA hamster muscles.38

In addition to biochemical and morphological effects, the different membrane PUFAs molar percentage was associated with a lower inflammatory potential mainly driven through resolvins and protectins,11,16,39,40 but also caused by ω3 EPA competitive inhibition of the cascade of AA, the precursor of ω6 derived proinflammatory eicosanoids (eg, TXA2, PGD2, PGE2, LTA1). EPA is an important anti-inflammatory reagent,11 and beneficial effects have been obtained in primary muscle cell culture from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients using inhibitors of the AA cascade.15 Consistently, in ALA- versus pellet-fed age-matched dystrophic hamsters, the inflammatory infiltrate and fibrosis, typical of dystrophic muscles, were almost absent.

The preservation of the intracellular signaling mechanisms in ALA-fed hamsters reverberates also on the negative myocyte degeneration/regeneration cycle typically characterizing dystrophic muscles. In fact, structurally and functionally unsuitable dystrophic myocytes from pellet-fed hamsters undergo intensive cell death and are usually substituted by a few new contractile cells generated by satellite cells and widespread the connective tissue.41 Consistently, in dystrophic hamster muscles, extensive apoptosis is associated with intensive cell proliferation, as witnessed by TERT and Cyclin 1 (data not shown) overexpression, also involving a large number of satellite cells, as demonstrated by the increased Pax7 signal. By contrast, the presence of cells expressing desmin, abundant in satellite cells during myogenesis41 and in regenerating fibers, as well as myogenin, marker of differentiated myoblasts,41 is very low. The extensive ALA effects on the cellular machinery discontinues the negative degeneration/regeneration cycle in dystrophic muscles. In fact, in ALA-treated muscles, cells affected by apoptosis or, conversely, by the overexpression of TERT and Cyclin 1 (data not shown), are rare, while Pax7 was expressed only in a limited number of cells. Instead, a strong expression of desmin indicated the presence, within the ALA treated dystrophic muscles, of a large number of regenerating myofibers, often organized in clusters able to concur to significantly remodel muscle structure.41 These myofibers displayed the ability to progress toward a differentiating stage, as demonstrated by the intensive expression of myogenin, which is expressed in mononucleated differentiating rather than in proliferating myoblasts.42

Taken together, it can be speculated that the muscle, as a system, rejects the presence of unsuitable contractile cells, as in muscular hereditary diseases, and triggers their apoptosis activating, at the same time, satellite cell proliferation in the attempt at substituting damaged myocytes. Unfortunately, the regenerative process is inefficient, because the new myocytes carry the same mutation and structural damage as the previous, so even they are destroyed by cell death processes. The empty space left within the muscle by the myocyte shortage is immediately filled with connective tissue. ALA, modifying the overall cell signaling, masks the hereditarily determined intrinsic myocyte damage, so that the muscle system does not sense their unsuitability and, thus, does not activate death processes. Consequently, the satellite cell regenerative capability, even if working faster, is not stressed and the muscle morphology and function is only minimally affected.

Finally, it must be noted that ALA efficiency in preventing dystrophic muscle damage is confined to animals in which the fatty acid is administered from weaning (ie, before the devastating irreversible effects of inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis). Conversely, adult dystrophic hamsters, in which ALA administration is started when the disease is well established, do not show any valuable myocyte preservation. So far, lipid nutritional therapy using conjugated linolenic acid has been investigated only as complement to corticosteroids intervention in the attempt to attenuate fat gain.8 Furthermore, this treatment, as well as many other different strategies3,4,16,43 in vain used, has been administered when fibrosis was irreversibly established and not before its onset, very likely owing to the lack of efficient techniques to anticipate the diagnosis.5,6,21 Because muscular dystrophy begins early in embryonic development,41,42,43,44 designing early treatment protocols is reasonable and mandatory to ameliorate the disease6,45 clinical outcome. In this context, present data envisage the first early cost-effective treatment protocol to prevent the dystrophic muscle damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Huda Shubeita for supplying MLC1 and MLC2 antibodies; Prof. Stefano Schiaffino for supplying clone BA-G5 and clone BF-35 antibodies for MHCs and Prof. Aiji Sakamoto for probes of α-DG and α-, β-, γ-, δ-SGs.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Paolo Di Nardo, M.D., Laboratorio di Cardiologia Molecolare e Cellulare, Dipartimento di Medicina Interna, Università di Roma Tor Vergata, Via Montpellier, 1, 00133 Roma, Italy. E-mail: dinardo@med.uniroma2.it.

Supported by Compagnia di S. Paolo, Torino and Syntech srl, Rome, Italy.

M.M. and P.D.N. contributed equally to this study.

References

- Guglieri M, Straub V, Bushby K, Lochmüller H. Limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:576–584. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32830efdc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello C, Faraso S, Sorrentino NC, Di Salvo G, Nusco E, Nigro G, Cutillo L, Calabrò R, Auricchio A, Nigro V. Disease rescue and increased lifespan in a model of cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy by combined AAV treatments. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinali M, Arechavala-Gomeza V, Feng L, Cirak S, Hunt D, Adkin C, Guglieri M, Ashton E, Abbs S, Nihoyannopoulos P, Garralda ME, Rutherford M, McCulley C, Popplewell L, Graham IR, Dickson G, Wood MJ, Wells DJ, Wilton SD, Kole R, Straub V, Bushby K, Sewry C, Morgan JE, Muntoni F. Local restoration of dystrophin expression with the morpholino oligomer AVI-4658 in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a single-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:918–928. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70211-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub V, Bushby K. Therapeutic possibilities in the autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley HG, De Luca A, Lynch GS, Grounds MD. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: focus on pharmaceutical and nutritional interventions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grounds MD. Two-tiered hypotheses for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1621–1625. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME. Creatine: endogenous metabolite, dietary, and therapeutic supplement. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:241–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne ET, Yasuda N, Bourgeois JM, Devries MC, Rodriguez MC, Yousuf J, Tarnopolsky MA. Nutritional theraphy improves function and complements corticosteroid intervention in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:66–77. doi: 10.1002/mus.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh SR, Edidin M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and membrane organization: elucidating mechanisms to balance immunotherapy and susceptibility to infection. Chem Phys Lipids. 2008;153:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui RA, Harvey KA, Zaloga GP, Stillwell W. Modulation of lipid rafts by Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and cancer: implications for use of lipids during nutrition support. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:74–88. doi: 10.1177/011542650702200174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull SP, Yates CM, Maskrey BH, O'Donnell VB, Madden J, Grimble RF, Calder PC, Nash GB, Rainger GE. Omega-3 Fatty acids and inflammation: novel interactions reveal a new step in neutrophil recruitment. PloS Biol. 2009;7:e1000177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DWL, Seo J, Davidson LA, Callaway ES, Fan YY, Lupton JR, Chapkin RS. N-3 PUFAS alter caveolae lipid composition and resident protein localization in mouse colon. FASEB J. 2004;1:1040–1042. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1430fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuelli L, Trono P, Marzocchella L, Mrozek MA, Palumbo C, Minieri M, Carotenuto F, Fiaccavento R, Nardi A, Galvano F, Di Nardo P, Modesti A, Bei R. Intercalated disk remodeling in delta-sarcoglycan-deficient hamsters fed with an alpha-linolenic acid-enriched diet. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorjão R, Azevedo-Martins AK, Rodrigues HG, Abdulkader F, Arcisio-Miranda M, Procopio J, Curi R. Comparative effects of DHA and EPA on cell function. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gáti I, Danielsson O, Betmark T, Ernerudh J, Ollinger K, Dizdar N. Effects of inhibitors of the arachidonic acid cascade on primary muscle culture from a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2007;77:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R345–R353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield FR, Tabas I. Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature. 2005;438:612–621. doi: 10.1038/nature04399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morise A, Mourot J, Riottot M, Weill P, Fénart E, Hermier D. Dose effect of alpha-linolenic acid on lipid metabolism in the hamster. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2005;45:405–418. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2005037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro V, de Sá Moreira E, Piluso G, Vainzof M, Belsito A, Politano L, Puca AA, Passos-Bueno MR, Zatz M. Autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. LGMD2F, is caused by a mutation in the delta-sarcoglycan gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:195–198. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo P, Fiaccavento R, Natali A, Minieri M, Sampaolesi M, Fusco A, Janmot C, Cuda G, Carbone A, Rogliani P, Peruzzi G. Embryonic gene expression in nonoverloaded ventricles of hereditary hypertrophic cardiomyopathic hamsters. Lab Invest. 1997;77:489–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace GQ, McNally EM. Mechanisms of muscle degeneration, regeneration, and repair in the muscular dystrophies. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:37–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuelli L, Bei R, Sacchetti P, Scappaticci I, Francalanci P, Albonici L, Coletti A, Palumbo C, Minieri M, Fiaccavento R, Carotenuto F, Fantini C, Carosella L, Modesti A, Di Nardo P. Beta-catenin accumulates in intercalated disks of hypertrophic cardiomyopathic hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambra R, Di Nardo P, Fantini C, Minieri M, Canali R, Natella F, Virgili F. Selective changes in DNA binding activity of transcription factors in UM-X7.1 cardiomyopathic hamsters. Life Sci. 2002;71:2369–2381. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiaccavento R, Carotenuto F, Minieri M, Masuelli L, Vecchini A, Bei R, Modesti A, Binaglia L, Fusco A, Bertoli A, Forte G, Carosella L, Di Nardo P. Alpha-linolenic acid-enriched diet prevents myocardial damage and expands longevity in cardiomyopathic hamsters. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1913–1924. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escribá PV, González-Ros JM, Goñi FM, Kinnunen PK, Vigh L, Sánchez-Magraner L, Fernández AM, Busquets X, Horváth I, Barceló-Coblijn G. Membranes: a meeting point for lipids, proteins and therapies. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:829–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto A, Ono K, Abe M, Jasmin G, Eki T, Murakami Y, Masaki T, Toyo-oka T, Hanaoka F. Both hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies are caused by mutation of the same gene, delta-sarcoglycan, in hamster: an animal model of disrupted dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13873–13878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Weisleder N, Ko JK, Komazaki S, Sunada Y, Nishi M, Takeshima H, Ma J. Membrane repair defects in muscular dystrophy are linked to altered interaction between MG53, caveolin-3, and dysferlin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15894–15902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetti C, Bado M, Broda P, Sotgia F, Bruno C, Galbiati F, Volonte D, Lucania G, Pavan A, Bonilla E, Lisanti MP, Cordone G. Impairment of caveolae formation and T-system disorganization in human muscular dystrophy with caveolin-3 deficiency. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:265–270. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DD, Wong VL, Esser KA. Expression of beta-catenin is necessary for physiological growth of adult skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C185–C188. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00644.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schakman O, Kalista S, Bertrand L, Lause P, Verniers J, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. Role of Akt/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin transduction pathway in the muscle anti-atrophy action of insulin-like growth factor-I in glucocorticoid-treated rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3900–3908. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CH, Mouly V, Cooper RN, Mamchaoui K, Bigot A, Shay JW, Di Santo JP, Butler-Browne GS, Wright WE. Cellular senescence in human myoblasts is overcome by human telomerase reverse transcriptase and cyclin-dependent kinase 4: consequences in aging muscle and therapeutic strategies for muscular dystrophies. Aging Cell. 2007;6:515–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchini A, Binaglia L, Bibeau M, Minieri M, Carotenuto F, Di Nardo P. Insulin deficiency and reduced expression of lipogenic enzymes in cardiomyopathic hamster. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:96–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benabdellah F, Yu H, Brunelle A, Laprévote O, De La Porte S. MALDI reveals membrane lipid profile reversion in MDX mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Rumeur E, Pottier S, Da Costa G, Metzinger L, Mouret L, Rocher C, Fourage M, Rondeau-Mouro C, Bondon A. Binding of the dystrophin second repeat to membrane di-oleyl phospholipids is dependent upon lipid packing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:648–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia TL, Kossugue PM, Paim JF, Zatz M, Anderson LV, Nigro V, Vainzof MA. A new evidence for the maintenance of the sarcoglycan complex in muscle sarcolemma in spite of the primary absence of delta-SG protein. J Mol Med. 2007;85:415–420. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen K, Bruusgaard JC. Nuclear domains during muscle atrophy: nuclei lost or paradigm lost? J Physiol. 2008;586:2675–2681. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw B, Canato M, Agatea L, Toniolo L, Mammucari C, Masiero E, Abraham R, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Inducible activation of Akt increases skeletal muscle mass and force without satellite cell activation. FASEB J. 2009;23:3896–3905. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JX, Höglund AS, Karlsson P, Lindblad J, Qaisar R, Aare S, Bengtsson E, Larsson L. Myonuclear domain size and myosin isoform expression in muscle fibres from mammals representing a 100,000-fold difference in body size. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:117–129. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NP, Misyak SA, Robertson JL, Bassaganya-Riera J, Grange RW. Immune-mediated mechanisms potentially regulate the disease time-course of duchenne muscular dystrophy and provide targets for therapeutic intervention. PM R. 2009;1:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli P, Levy BD. Resolvins and protectins: mediating solutions to inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:960–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciliot S, Schiaffino S. Regeneration of mammalian skeletal muscle. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:906–914. doi: 10.2174/138161210790883453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carosio S, Berardinelli MG, Aucello M, Musarò A. Impact of ageing on muscle cell regeneration. Ageing Res Rev 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillwell E, Vitale J, Zhao Q, Beck A, Schneider J, Khadim F, Elson G, Altaf A, Yehia G, Dong JH, Liu J, Mark W, Bhaumik M, Grange R, Fraidenraich D. Blastocyst injection of wild type embryonic stem cells induces global corrections in mdx mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick D, Stadler LK, Larner D, Smith J. Muscular dystrophy begins early in embryonic development deriving from stem cell loss and disrupted skeletal muscle formation. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:374–388. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe GM, Shavlakadze T, Roberts P, Davies MJ, McGeachie JK, Grounds MD. Age influences the early events of skeletal muscle regeneration: studies of whole muscle grafts transplanted between young (8 weeks) and old (13–21 months) mice. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:550–562. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]