Abstract

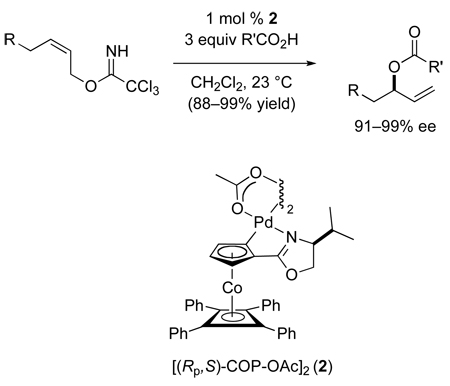

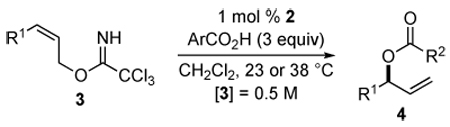

A broadly useful catalytic enantioselective synthesis of branched allylic esters from prochiral (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols has been developed. The starting allylic alcohol is converted to its trichloroacetimidate intermediate by reaction with trichloroacetonitrile, either in situ or in a separate step, and this intermediate undergoes clean enantioselective SN2′ substitution with a variety of carboxylic acids in the presence of the palladium(II) catalyst (Rp,S)-di-μ -acetatobis[(η5-2-(2'-(4'-methylethyl)oxazolinyl)cyclopentadienyl,1-C,3'-N)(η4-tetraphenylcyclobutadiene)cobalt]dipalladium, (Rp,S)-[COP-OAc]2 or its enantiomer. The scope and limitations of this useful catalytic asymmetric allylic esterification are defined.

Introduction

Branched allylic alcohols (1-alken-3-ols) are versatile intermediates for the synthesis of a wide variety of organic compounds.1,2 When chiral, these alcohols are often accessed in enantioenriched form by kinetic resolution,3,4 although their synthesis using enantioselective chemical catalysts is becoming increasingly important. For example, they can be assembled enantioselectively by forming allylic C–H or C–C bonds by catalytic asymmetric reduction of enones5 or catalytic asymmetric addition of vinyl nucleophiles to aldehydes.6,7 Alternatively, branched allylic alcohols can be prepared in enantioselective fashion by formation of the allylic C–O bond. Numerous catalytic asymmetric allylic alkylations of alkoxides, phenoxides, or carboxylates with Pd(0),8,9,10 Ir(I),11 Rh(III),12 Cu(II),13 and Ru(II)14 catalysts have been described.15 Of these, the iridium-catalyzed methods are of particular importance because iridium(I) η3-allyl intermediates react preferentially with nucleophiles at the more-substituted end of the allyl fragment.16 Using phosphoramidite ligands, Hartwig has shown that Ir-catalyzed allylation of phenoxides and alkoxides can generate the corresponding allylic ethers in high enantiomeric purity and up to 99:1 branched to linear selectivity. In principle this method could deliver branched allylic alcohols in high enantiomeric purity; however, conversion of an allylic benzyl ether or related intermediate to the parent allylic alcohol is complicated by the presence of the C=C π-bond.

With Ir-phosphoramidite catalysts, Carreira recently reported the two-step conversion of allylic carbonates to enantioenriched branched allylic alcohols using silanolates as hydroxide equivalents.17 In this case, the allylic silyl ether product is transformed in high yield to the parent allylic alcohol by reaction with 30% aqueous NaOH in methanol.

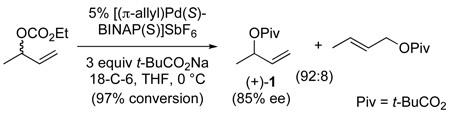

Branched allylic esters are particularly convenient precursors of branched allylic alcohols and also important synthetic intermediates in their own right. Prior to our report in 2005, there was only a single example of the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes by forming the allylic C–O bond.18 In that disclosure, the reaction of sodium pivalate with racemic 3-buten-2-yl ethyl carbonate and a palladium-BINAP(S) catalyst was reported to take place with a branched-to-linear ratio of 92:8 to give (+)-3-buten-2-yl tert-butyl carbonate (1) in 85% ee (eq 1).

|

(1) |

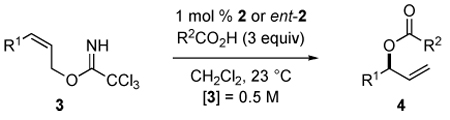

In 2005, we described the most general catalytic asymmetric allylic esterification reaction yet reported. In this process, trichloroacetimidate derivatives of prochiral (Z)-allylic alcohols were shown to react with carboxylic acids in the presence of 1 mol % of the Pd(II) catalyst [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2)19 or its enantiomer to give a variety of 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes in high yields and high enantiomeric purity (eq 2).20 These reactions proceeded at room temperature with exceptionally high branched-to-linear ratios (up to 800:1) to give ester products, which are easily transformed to the parent branched allylic alcohol. In this article we delineate the scope and limitations of this new catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral allylic esters. In the accompanying paper, we describe experiments that provide insight into the mechanism of this transformation.21

|

(2) |

Results and Discussion

Initial Studies and Optimization

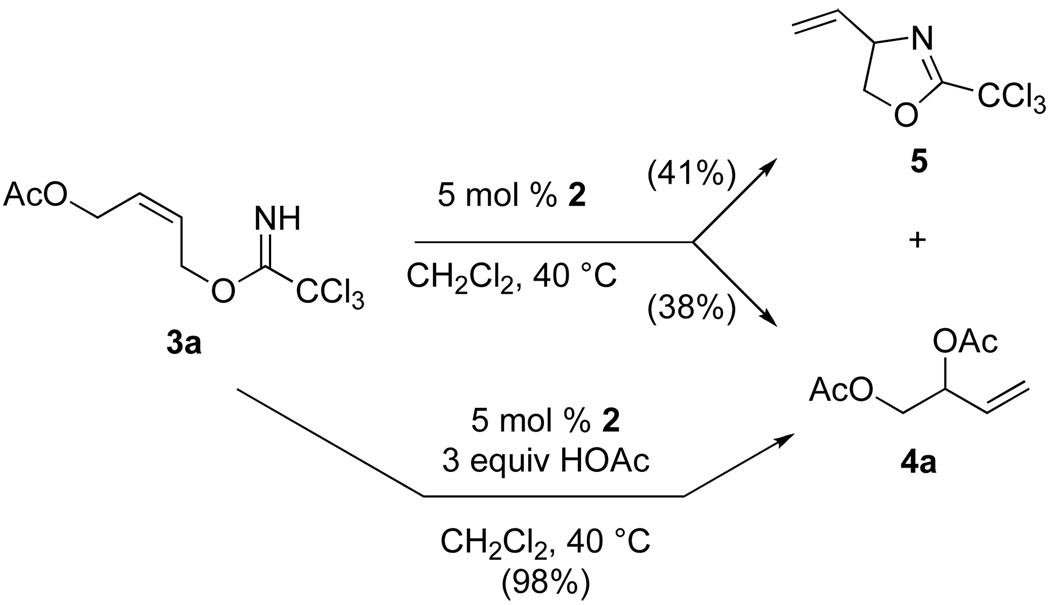

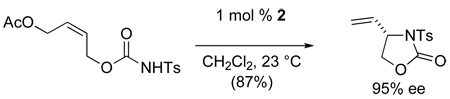

Several years ago we reported that [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2) was a preferred catalyst for catalytic asymmetric intramolecular aminopalladation of (Z)-allylic N-tosylcarbamates to form 3-tosyl-4-vinyloxazolidin-2-ones (eq 3).22 It was in attempting to extend this reaction to the formation of enantioenriched 4-vinyloxazolidines that the catalytic asymmetric allylic esterification reaction was discovered. In a key early experiment, exposure of acetoxybutenyl trichloroacetimidate 3a to 5 mol % of COP catalyst 2 at room temperature formed a ~1:1 mixture of 4-vinyloxazolidine 5 and 1,2-diacetoxy-3-butene (4a) (Scheme 1). This result suggested that SN2′ displacement of the imidate by acetic acid was occurring competitively with intramolecular cyclization of the imidate nitrogen. Indeed, in the presence of excess acetic acid, imidate 3a was converted into butenyl diacetate 4a in 98% yield, with no competing intramolecular cyclization being observed.

|

(3) |

Scheme 1.

Discovery of Palladium-Catalyzed 3-Acyloxy-1-alkene Synthesis

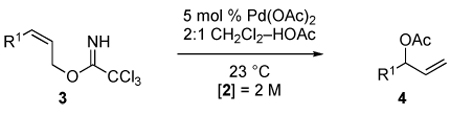

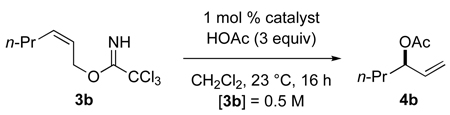

Palladium acetate was identified as an effective catalyst for the synthesis of racemic 3-acetoxy-1-alkenes from trichloroacetimidate derivatives of (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols (Table 1). These reactions were optimally carried out at room temperature and proceeded within hours in the presence of 5 mol % of Pd(OAc)2. No conversion to allylic acetate products was observed in the absence of the palladium acetate. At 38 °C, trichloroacetimidate 3b (R1 = n-Pr) gave allylic acetate 4b in lower yield, as rapid precipitation of palladium black was observed (entry 2). Although not extensively investigated in these early experiments, catalyst loadings as low as 1 mol % could be employed (entry 3). Selectivity for forming the branched allylic acetate was high, as signals diagnostic of the linear allylic acetate product were not detected by 1H NMR analysis of crude reaction products.

Table 1.

Palladium Acetate-Catalyzed Formation of Racemic 3-Acetoxy-1-alkenes

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | temp [°C] |

time [h] |

4 | yield [%]a |

| 1 | n-Pr | 23 | 5 | 4b | 96 |

| 2 | n-Pr | 38 | 1 | 4b | 52 |

| 3b | (CH2)2Ph | 23 | 10 | 4c | 70 |

| 4 | i-Bu | 23 | 2 | 4d | 85 |

| 5 | CH2OH | 23 | 2 | 4e | 82 |

| 6 | CH2OAc | 23 | 2 | 4a | 99 |

| 7 | CH2OPMB | 23 | 5 | 4f | 91 |

| 8 | (CH2)3OTBS | 23 | 4 | 4g | 83 |

Yield of pure product.

1 mol % catalyst loading.

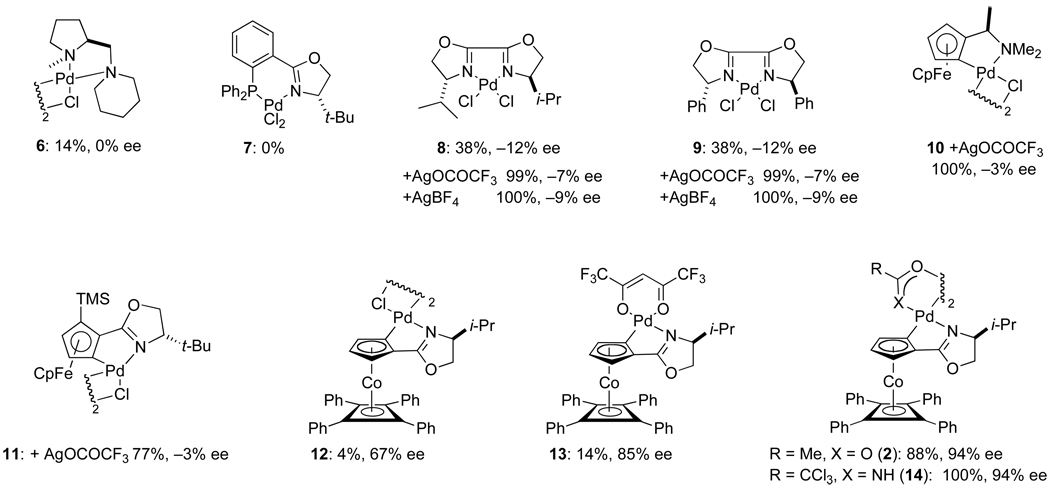

In light of these initial discoveries, the reaction of (Z)-2-hexenyl imidate 3b with acetic acid to form 3-acetoxy-1-hexene (4b) was examined in the presence of a variety of enantiomerically pure Pd(II) complexes (eq 4 and Figure 1).23 Cationic palladium diamine complex 624 and palladium dichloride

|

(4) |

PHOX complex 7 were kinetically ineffective catalysts for this transformation, as were palladium dichloride bis-oxazoline complexes 8 and 9. Catalysis rate increased markedly when complexes 8 and 9 were pretreated with 4 equiv of silver salts, however enantioselectivity in forming 4b was very low with these cationic palladium(II) complexes. Cationic complexes generated from the palladacyclic halide-bridged dimeric complexes 1025 and 1126 also showed good catalytic rates, but negligible enantioselectivity. Higher enantioselectivities were realized with the palladacyclic COP complexes 12, [(Rp,S)-COP-Cl]2,19 and 13, (Rp,S)-COP-hfacac;27 however catalytic rates were poor. The optimal combination of enantioselectivity and rate was achieved with acetate-bridged COP complex 2, [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 and the amidate-bridged (Rp,S)-COP complex 14,28 both of which formed the (S)-allylic ester 4b in 94% ee and high yield. Because COP complexes 2 and 14 readily interconvert in the presence of excess acetic acid,21 and both enantiomers of [COP-OAc]2 are commercially available, [COP-OAc]2 (2) was chosen for further investigation.

Figure 1.

Yield and enantioselectivity in forming (R)-3-acetoxy-1-hexene (4b) using enantiomerically pure palladium(II) complexes under the conditions specified in equation 423

Several studies were carried out to optimize this catalytic asymmetric synthesis of allylic esters. Under standard conditions—1 mol % [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2), 3 equiv HOAc, 0.5 M imidate, 23 °C—the conversion of (Z)-2-hexen-1-yl trichloroacetimidate (3b) to (R)-3-acetoxy-1-hexene (4b) was studied in various solvents with the following results: CH2Cl2 (88%, 17 h), THF (69%, 16 h), benzene (43%, 16 h), MeCN (8%, 17 h). With the exception of the coordinating solvent MeCN, the enantiopurity of ester product 4b was nearly identical in the solvents surveyed (91–94% ee). Trichloroacetamide was identified as a product by GC analysis.

The effect of temperature on the transformation of 3b → 4b was surveyed in CH2Cl2 using 1 mol % [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2), 3 equiv HOAc, and an imidate concentration of 0.5 M. The reaction was quite slow at 0 °C, with (R)-allylic ester 4b being formed in only 17% yield (96% ee) after 17 h. Under identical conditions, (R)-3-acetoxy-1-hexene (4b) was produced in 88% yield (94% ee) at room temperature and 94% yield at 38 °C, albeit with reduced enantioselectivity (87% ee). We conclude that in terms of both rate and enantioselectivity, this catalytic enantioselective allylic esterification is best carried out at room temperature; however, for slow reactions, increasing the reaction temperature to 38 °C to increase catalysis rate would only slightly decrease enantioselectivity.

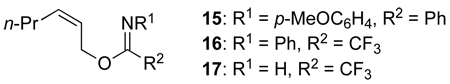

We also briefly examined other carboxyl nucleophiles and imidate leaving groups. The use of sodium or ammonium acetate, instead of acetic acid, led to no product formation, which is not surprising as protonation of the imidate would presumably be required to generate the competent leaving group, trichloroacetamide.29 N-Arylimidate 15, which is a good substrate for [COP-Cl]2-catalyzed allylic imidate rearrangement,30 did not to react with acetic acid in the presence of [COP-OAc]2, nor did allylic trifluoroacetimidates 16 or 17. Thus, allylic trichloroacetimidates are the preferred substrates, which is attractive as they are the most convenient imidates to prepare from allylic alcohols.31

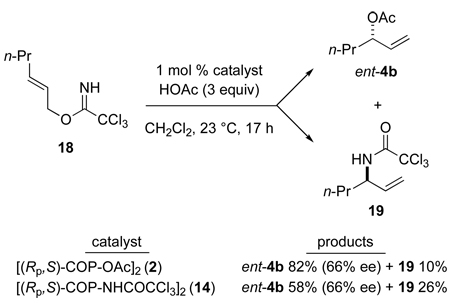

This catalytic asymmetric synthesis of allylic esters is not useful in the reactions of E allylic imidates. For example, reaction of (E)-trichloroacetimidate 18 with acetic acid catalyzed by 1 mol % of [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2) gives the allylic ester product, in this case ent-4b, in only 66% ee (eq 5). The [COP-Cl]2-catalyzed asymmetric rearrangement of allylic trichloroimidates to give allylic trichloroacetamides is known to proceed significantly faster with the E stereoisomer of an allylic imidate,31 a trend that is also seen with [COP-OAc]2. Thus, the yield of allylic ester is lower in the E series, as allylic trichloroacetimidate rearrangement to form allylic amide 19 becomes a competing process (eq 5).32 It was recently discovered that the amidate-bridged COP catalyst 14 enabled the formation of branched allylic aryl ethers from (E)-allylic trichloroacetimidates, because the allylic imidate rearrangement is somewhat slower with this catalyst.28 However, catalyst 14 also performed poorly in the reaction depicted in eq 5.33

|

(5) |

Scope and Limitations of Catalytic Enantioselective Allylic Esterification

Using the conditions identified in our optimization studies, a series of trichloroacetimidates of (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols were allowed to react with acetic or benzoic acid in the presence of 1 mol % of [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2) or its enantiomer ent-2 (Table 2). With but one exception, the branched product was formed with high selectivity, the linear product not being observed by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction product. 3-Acetoxy- (entry 1) and 3-benzoyloxy-1-hexene (entry 2) were produced in identical enantiomeric purities of 94% ee. The yield was somewhat higher (98%) for the latter, likely reflecting the lower volatility and associated higher recovery of this product from chromatographic purification. Branching at the 5-position was well tolerated (entry 3), but branching at the 4-position resulted in a marked decrease in catalysis rate (entry 4). Furthermore, in the reaction of cyclohexyl substrate 3d, the branched-to-linear ratio was reduced to 92:8. Imidate 3f, bearing a hydroxyl group, was a suitable substrate for this reaction, producing acetate 4e in 92% yield and 97% enantiomeric excess (entry 6). Ester, ether and silyl ether substituents were also well tolerated (entries 7–10). The absolute configuration was established experimentally for seven of the allylic ester products reported in Table 2. In all cases, the (Rp,S) enantiomer of [COP-OAc]2 provided the allylic ester enantiomer depicted in eq 2. The opposite enantiomer was produced with the enantiomeric catalyst ent-2 (entry 10).

Table 2.

Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of 3-Acyloxy-1-alkenesa

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | R1 | R2 | 3 | time [h] | 4 | yield [%]b | ee [%]c (config) |

| 1 | n-Pr | Me | 3b | 17 | 4b | 88 | 94 (R)d |

| 2e | n-Pr | Ph | 3b | 16 | 4b | 98 | 94 (R)f |

| 3 | i-Bu | Me | 3c | 14 | 4d | 96 | 93 |

| 4 | Cy | Me | 3d | 48 | 4h | 45 | 90 |

| 5 | (CH2)2Ph | Ph | 3e | 17 | 4i | 85 | 93g |

| 6 | CH2OH | Me | 3f | 17 | 4e | 92 | 97 (S)h |

| 7 | CH2OAc | Me | 3g | 8 | 4a | 90 | 99 (S)h |

| 8 | CH2OPMB | Me | 3h | 16 | 4f | 93 | 99 (S)h |

| 9 | (CH2)3OTBS | Me | 3i | 17 | 4g | 98 | 93 (R)i |

| 10j | (CH2)3OTBS | Ph | 3i | 20 | 4j | 93 | 99(S)d,g |

[(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2) except for entry 10 that used ent-2.

Yield of pure product.

Determined by GC analysis unless otherwise indicated; results of duplicate experiments agreed within ±2%.

Absolute configuration determined by analysis of the Mosher ester.34

[3] = 0.17 M.

Absolute configuration by optical rotation.35

Determined by HPLC analysis.

Absolute configuration by synthesis from (S)-3-butene-1,2-diol.

Absolute configuration by optical rotation.36

Catalyst was ent-2.

With the exception of the reaction reported in entry 4, the [COP-OAc]2-catalyzed synthesis of allylic esters produces branched products in excellent yield and high enantiomeric excess; no significant by-products other than traces of the COP catalyst were apparent by 1H NMR analysis of the concentrated crude reaction mixture (see Figure in Supporting Information). Capillary GC analysis failed to detect linear products [(E)- or (Z)-2-hexen-1-yl acetate] in the reaction of entry 1 under conditions whereby 1 part in 800 of the linear product would have been observed. However, at high acetic acid concentrations (> 4 M in CH2Cl2), the branched-to-linear ratio decreases markedly. In the presence of water (>0.01% v/v), (Z)-hex-2-enyl trichloroacetate, which results from hydrolysis of the trichloroacetimidate, was identified as a minor by-product in the reaction of entry 1. This by-product was not formed when commercial glacial acetic acid was used without distillation.

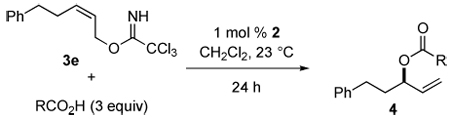

Prior to further surveying the scope of this catalytic asymmetric synthesis of allylic esters, a series of 1H NMR experiments were conducted to determine the relative reactivity of ten diverse carboxylic acids with imidate 3e (Table 3). Not surprisingly, the reaction was slower with the bulky carboxylic acids pivalic acid and 1-adamantanecarboxylic acid (Table 3, entries 5 and 7). There was no apparent correlation between percent conversion and pKa for the less sterically demanding acids. However, for carboxylic acids of pKa 4 or lower, conversion to allylic ester 4 was unsatisfactory. In three of these cases (entries 6, 9, and 10), the major product was the linear (E)-allylic ester, with the allylic imidate disappearing within hours in the presence of the strongest acid (entries 9 and 10). Control experiments show significant formation of linear esters when imidate 3e is exposed to methoxyacetic, o-chlorobenzoic or dichloroacetic acid without catalyst 2 present.

Table 3.

Relative Reactivity of Carboxylic Acids with Allylic Imidate 3e in the Presence of 1 mol % of COP Catalyst 2a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | pKa | % conversionb | |

| 10h | 24h | |||

| 1 | o-ClC6H4CH2 | 4.1 | 55 | 79 |

| 2 | Me | 4.8 | 65 | 89 |

| 3 | Ph | 4.2 | 62 | 84 |

| 4 | p-MeC6H4 | 4.4 | 42 | 67 |

| 5 | t-Bu | 5.0 | 24 | 40 |

| 6 | MeOCH2 | 3.6 | 13d | 38d |

| 7 | 1-adamantyl | 6.8 | 16 | 26 |

| 8 | ClCH2CH2 | 4.0 | 18c | 21 |

| 9 | o-ClC6H4 | 2.9 | 16d | 18d |

| 10 | Cl2CH | 1.3 | 18d | 18d |

3 Equiv RCO2H, 1 mol % 2, rt, [3e] = 0.5 M.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of ester product 4 using an internal standard.

% Conversion at 3 h was 12%.

The major product of these reactions was the linear allylic acetate.

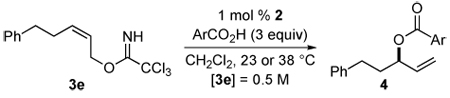

We next examined the [COP-OAc]2-catalyzed reaction of a series of aromatic carboxylic acids with (Z)-trichloroacetimidate 3e (Table 4). Only p-toluic acid and 2-napthoic acid were appreciably soluble in CH2Cl2 allowing catalysis reactions to be carried out conveniently under our standard conditions (entries 1 and 2): 1 mol % [(Rp,S)-COP-OAc]2 (2), 3 equiv HOAc, 0.5 M imidate, 23 °C.37 To increase the solubility of the acid, reactions with other substituted benzoic acids were conducted at 38 °C. Benzoic acids with both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups provided allylic ester products 4k–p in high yield (79–95%) and excellent enantioselectivity (93–97% ee) (entries 1–3 and 5–7). Only the reaction of o-chlorobenzoic acid was unsatisfactory, providing allylic ester 4q in poor yield and low enantioselectivity (entry 8). With this sterically hindered, more acidic (pKa = 2.94) acid, the uncatalyzed background reaction occurred at a competitive rate.38 In an attempt to improve the solubility of the carboxylic acid nucleophile at room temperature, the reaction of imidate 3e with p-methoxybenzoic acid was carried in 10:1 CH2Cl2/THF (entry 4). Although enantioselectivity was slighly higher (97 vs 95% ee) than the corresponding reaction conducted at 38 °C in CH2Cl2, the yield after a reaction time of 22 h was considerably lower.

Table 4.

Scope of the Enantioselective Reaction of Aromatic Carboxylic Acids with Imidate 3e to Form 3-Acyloxy-1-alkenes

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Ar | time [h] |

temp [°C] |

4 | yield [%]a |

ee [%]b |

| 1 | p-MeC6H4 | 17 | 23 | 4k | 85 | 93 |

| 2c | 2-naphthyl | 17 | 23 | 4l | 87 | 96 |

| 3 | p-MeOC6H4 | 22 | 38 | 4m | 79 | 86 |

| 4d | p-MeOC6H4 | 22 | 23 | 4m | 46 | 95 |

| 5 | p-PhC6H4 | 19 | 38 | 4n | 95 | 97e |

| 6 | p-ClC6H4 | 16 | 38 | 4o | 86 | 97 |

| 7 | p-NO2C6H4 | 22 | 38 | 4p | 65 | 87 |

| 8 | o-ClC6H4 | 18 | 38 | 4q | 24 | 46–53 |

Yield of pure product after silica gel chromatography.

Determined by HPLC analysis unless otherwise noted; results of duplicate experiments agreed within ±3%; absolute configuration assigned in analogy with products reported in Table 2.

3b used as substrate, [3b] = 0.17 M.

10:1 CH2Cl2:THF used as solvent.

Determined after conversion to benzoate ester 4i.

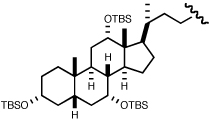

A variety of aliphatic carboxylic acids can be successfully employed in this enantioselective construction of 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes (Table 5). Phenylacetic acid and isobutyric acid react in high yield at room temperature to give the corresponding ester products 4r and 4s in high yield and enantioselectivity (entries 1, 2). Reactions with bulkier carboxylic acids (entries 3,4), or less soluble carboxylic acids (entries 5,6), were optimally conducted at 38 °C to give ester products 4t–w in useful yields (68–95%) and good enantioselectivities (86–96% ee). The successful use of indole-3-acetic acid and TBS-protected cholic acid (entries 5,6) suggest the potential broad scope of this method. Only the reaction with acrylic acid was unsatisfactory, providing branched allylic ester product in low yield (entry 7).

Table 5.

Scope of the Enantioselective Reaction of Aliphatic Carboxylic Acids with Imidate 3 to Form 3-Acyloxy-1-alkenes

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | 3 | time [h] | temp [°C] | 4 | yield [%]a | ee [%]b |

| 1c | n-Pr | CH2Ph | 3b | 20 | 23 | 4r | 90 | 91 |

| 2 | n-Pr | i-Pr | 3b | 21 | 23 | 4s | 89 | 92d |

| 3 | (CH2)2Ph | t-Bu | 3e | 48 | 38 | 4t | 95 | 94e |

| 4 | (CH2)2Ph | 1-adamantyl | 3e | 48 | 38 | 4u | 68 | 86f |

| 5 | (CH2)2Ph |  |

3e | 17 | 38 | 4v | 65 | 96 |

| 6 | (CH2)2Ph |  |

3e | 48 | 38 | 4w | 91 | 91e |

| 7 | (CH2)2Ph | CH=CH2 | 3e | 48 | 38 | 4x | 37 | nd |

Yield of pure product after silica gel chromatography.

Determined by HPLC analysis unless otherwise noted; results of duplicate experiments agreed within ±3%; absolute configuration assigned in analogy with products reported in Table 2.

[3] = 0.17 M.

Determined by GC analysis.

Determined after conversion to benzoate ester 4h.

Determined by analysis of the Mosher ester.34

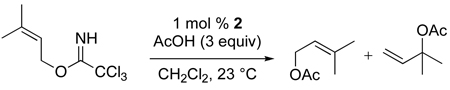

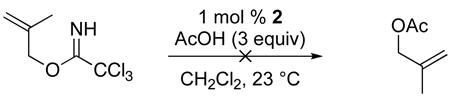

Several additional limitations to this method have been identified. Attempts to employ α-amino acids or nicotinic acid failed, the former likely the result of the low solubility of the zwiterionic nucleophile and the latter from competitive nitrogen-palladium coordination.39 Allylic imidates with additional alkyl substituents at C2 or C3 were also unsuitable substrates for the [COP-OAc]2-catalyzed allylic ester synthesis. Substitution at C3 is not tolerated, because the uncatalyzed background reaction dominates, resulting in the formation of mixtures of the linear and racemic-branched tertiary allylic ester products (e.g. eq 6). 2-Methyl-2-propenyl trichloroacetimidate does not react with carboxylic acids in the presence of [COP-OAc]2, undoubtedly because the oxypalladation step is disfavored in this case (eq 7).

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

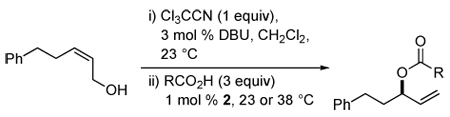

The conversion of prochiral (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols to enantioenriched 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes can be accomplished in a one-pot reaction, as allylic trichloroacetimidates are conveniently prepared in CH2Cl2 from the DBU-catalyzed addition of allylic alcohols to trichloroacetonitrile.40 In the one-pot sequence, the allylic trichloroacetimidate is generated by reaction of the allylic alcohol with 1 equiv of Cl3CCN in the presence of 3 mol % of DBU; after imidate formation is complete, 3 equiv of a carboxylic acid and 1 mol % (Rp,S)-[COP-OAc]2 (2) are added, and the allylic esterification is allowed to proceed either at room temperature or at 38 °C (Table 5). This process provided the 3-acyloxy-1-alkene products 4c, 4i, 4m, and 4v in useful yields and enantiomeric excesses that are slightly lower than those realized in the two-step sequence (Tables 2, 4 and 5). One important consideration is the necessity for complete consumption of trichloroacetonitrile prior to addition of the catalyst. Addition of the carboxylic acid and [COP-OAc]2 (2) to reactions in which imidate formation was incomplete provided the allylic ester in low yield and unconsumed allylic trichloroacetimidate 3e.41 In order to achieve consistent results, the in situ generation of the trichloroacetimidate intermediates was carried out for 7 h to ensure full consumption of trichloroacetonitrile before the carboxylic acid and palladium catalyst were added.

Conclusion

A useful catalytic enantioselective synthesis of branched allylic esters from prochiral (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols has been developed. The starting allylic alcohol is converted to its trichloroacetimidate intermediate by reaction with trichloroacetonitrile, either in situ or in a separate step, and this intermediate suffers clean enantioselective SN2′ substitution with a variety of carboxylic acids in the presence of the palladium(II) catalyst, [COP-OAc]2. The allylic substitution reaction proceeds at, or just slightly above, room temperature, using catalyst loadings of 1 mol % to provide a variety of 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes in good yields (60–98%) and excellent enantiomeric purities (86–99% ee). Either enantiomer of the allylic ester product can be prepared, as both enantiomers of [COP-OAc]2 are commercially available. A variety of carboxylic acids, including ones containing additional heteroatom functionalities, react successfully. However, carboxylic acids having pKa’s much lower than 4 cannot be used, because acid-promoted ionization of the allylic trichloroacetimidate is a competitive side reaction with these acids. The reaction is limited also to primary (Z)-2-alkene-1-ols having disubstituted double bonds.

Exceptionally high branched-to-linear ratios are a distinctive feature of the catalytic enantioselective allylic esterification reaction discussed herein: typically only the branched product can be detected by 1H NMR analysis of crude reaction products, with b/l ratios of >800 being documented. This feature alone suggests a novel mechanism for this Pd(II)-catalyzed substitution reaction, which is the subject of the accompanying article.21

The utility of this synthesis of enantioenriched allylic esters has been illustrated recently in the construction of 1,3-polyol arrays42 and the total synthesis of the 12-membered macrolide, (+)-chloriolide. 43

Supplementary Material

Table 6.

One-Pot Enantioselective Synthesis of Branched Allylic Esters

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | temp [°C] |

4 | yield [%]a |

ee [%] |

| 1 | Me | 23 | 4c | 76 | 92b |

| 2 | Ph | 38 | 4i | 72 | 80c |

| 3 | p-MeOC6H4 | 38 | 4m | 94 | 90c |

| 4 |  |

38 | 4v | 64 | 87d |

Yield of pure product after silica gel chromatography.

Determined by GC analysis.

Determined by SFC analysis.

Determined by HPLC analysis.

Acknowledgement

We thank NSF (CHE-9726471 and CHE-0616201), NIH (NIGMS-12389), Allergan, and Amgen for financial support, and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a Feodor Lynen Fellowship for S. F. K. NMR and mass spectra were performed on instruments acquired with the assistance of NSF and NIH shared instrumentation grants.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: General methods, experimental procedures, NMR, HPLC, SFC and GC data of new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1. Enantioenriched allylic esters are a ubiquitous intermediate for the synthesis of complex molecules. Selected recent examples include: Shimizu Y, Shi S-L, Usuda H, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:1103–1106. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906678. Crimmins MT, Jacobs DL. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2695–2698. doi: 10.1021/ol900814w. Stivala CE, Zakarian A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3774–3776. doi: 10.1021/ja800435j.

- 2.For a comprehensive review of the synthesis of allylic alcohols, see: Hodgson DM, Humphreys PG. In: Science of Synthesis: Houben-Weyl Methods of Molecular Transformations. Clayden JP, editor. Vol. 36. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2007. pp. 583–665.

- 3.Enzymatic kinetic resolution: García-Urdiales E, Alfonso I, Gotor V. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:313–354. doi: 10.1021/cr040640a. Carrea G, Riva S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:2226–2254. Drauz K, Waldmann H, editors. Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1995. Faber K. Biotransformations in Organic Chemistry. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer; 1997. pp. 201–205.

- 4.Palladium-catalyzed kinetic resolution: Ebner DC, Bagdanoff JT, Ferreira EM, McFadden RM, Caspi DD, Trend RM, Stoltz BM. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:12978–12992. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902172. Gligorich KM, Sigman MS. Chem. Commun. 2009:3854–3867. doi: 10.1039/b902868d. Trend RM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15957–15966. doi: 10.1021/ja804955e. Mueller JA, Cowell A, Chandler BD, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14817–14824. doi: 10.1021/ja053195p.

- 5.(a) Sandoval CA, Ohkuma T, Muñiz K, Noyori R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13490–13503. doi: 10.1021/ja030272c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Noyori R, Ohkuma T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:40–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1986–2012. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Pu L, Yu H-B. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:757–824. doi: 10.1021/cr000411y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oppolzer W, Radinov RN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:5645–5648. [Google Scholar]

- 7.A novel catalytic asymmetric approach involving Cu-catalyzed catalytic asymetric allylic alkylation was described recently: Geurts K, Fletcher SP, van Zijl AW, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Pure Appl. Chem. 2008;80:1025–1037. Harutyunyan SR, den Hartog T, Geurts K, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2824–2852. doi: 10.1021/cr068424k.

- 8.Trost BM, Organ MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:10320–10321. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For comprehensive reviews see: Trost BM. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:5813–5837. doi: 10.1021/jo0491004. Trost BM, Crawley ML. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2921–2943. doi: 10.1021/cr020027w.

- 10.Direct palladium-catalyzed allylic C–H oxidation to provide 3-acyloxy-1-alkenes in modest enantioselectivity has been reported by the White group: Covell DJ, White MC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6448–6451. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802106.

- 11.(a) Stanley LM, Bai C, Ueda M, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8918–8920. doi: 10.1021/ja103779e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ueno S, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1928–1931. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shu C, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4794–4797. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) López F, Ohmura T, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3426–3427. doi: 10.1021/ja029790y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Evans PA, Leahy DK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7882–7883. doi: 10.1021/ja026337d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans PA, Leahy DK, Slieker LM.Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2003143613–3618.16946800 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzman-Martinez A, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Kanbayashi N, Onitsuka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1206–1207. doi: 10.1021/ja908456b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Onitsuka K, Okuda H, Sasai H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1454–1457. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a recent review of enantioselective allylation reactions, see: Lu Z, Ma S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:258–297. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113.

- 16.For a recent review, see: Helmchen G, Dahnz A, Dübon P, Schelwies M, Weihofen R. Chem. Commun. 2007:675–691. doi: 10.1039/b614169b.

- 17.Lyothier I, Defieber C, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6204–6207. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faller JW, Wilt JC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7613–7616. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Anderson CE, Kirsch SF, Overman LE, Richards CJ, Watson MP. Org. Synth. 2007;84:148–155. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderson CE, Overman LE, Richards CJ, Watson MP, White NS. Org. Synth. 2007;84:139–147. [Google Scholar]; (c) Stevens AM, Richards CJ. Organometallics. 1999;18:1346–1348. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirsch SF, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2866–2867. doi: 10.1021/ja0425583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon J, Kirsch SF, Overman LE, Sneddon HF. following paper in this issue. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch SF, Overman LE. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:2859–2861. doi: 10.1021/jo047763f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Cationic complexes were generated from chloride-bridged dimer precursors by pretreatment at room temperature with 4 equiv of the silver salt specified in Figure 1. (b) A negative sign before the % ee indicates that ent-3b was produced in excess.

- 24.Calter M, Hollis TK, Overman LE, Ziller J, Zipp GG. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:1449–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Hollis TK, Overman LE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:8837–8840. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sokolov VI, Troitskaya LL, Reutov J. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;133:C28–C30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donde Y, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2933–2934. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirsch SF, Overman LE, Watson MP. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8101–8104. doi: 10.1021/jo0487092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olson AC, Overman LE, Sneddon HF, Ziller JW. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:3186–3192. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200900678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estimated pKa = 12.8; calculated using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software, version 8.14.

- 30.Overman LE, Owen CE, Pavan MM. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1809–1812. doi: 10.1021/ol0271786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter NE, Overman LE. Org. React. 2005;56:1–107. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Under identical conditions, allylic trichloroacetamide is not detected in the corresponding reaction of (Z)-imidate 3b.

- 33.This result is not surprising in light of the rapid interconversion of catalysts 2 and 14 in the presence of acetic acid.

- 34.Dale JA, Mosher HS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:512–519. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin VS, Ode JM, Palazón JM, Soler MA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1992;3:573–580. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enders D, Nguyen D. Synthesis. 2000:2092–2098. [Google Scholar]

- 37.None of the reactions reported in Table 4 were homogeneous.

- 38.In the absence of catalyst 2, reaction of 3e with o-chlorobenzoic acid provided ~20% conversion to the linear o-chlorobenzoate ester after 24 h.

- 39.Watson MP, Overman LE, Bergman RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5031–5044. doi: 10.1021/ja0676962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oishi T, Ando K, Inomiya K, Sato H, Iida M, Chida N. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2002;75:1927–1947. [Google Scholar]

- 41.We have found that the addition of alcohols to trichloroacetonitrile is catalyzed by [COP-OAc]2 (2) at room temperature. However, this reaction is low yielding because the catalyst becomes poisoned, presumably from the formation of a minor byproduct.

- 42.(a) Menz H, Kirsch SF. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5634–5637. doi: 10.1021/ol902135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Binder JT, Kirsch SF. Chem. Commun. 2007:4164–4166. doi: 10.1039/b708248g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haug TT, Kirsch SF. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:991–993. doi: 10.1039/b925644j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.