Abstract

Background

The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm Program was designed to ensure the full range of patient treatment preferences are honored throughout the health care system. Data are lacking about the use of POLST in the hospice setting.

Objective

To assess use of the POLST by hospice programs, attitudes of hospice personnel toward POLST, the effect of POLST on the use of life-sustaining treatments, and the types of treatments options selected by hospice patients.

Design

A telephone survey was conducted of all hospice programs in three states (Oregon, Wisconsin, and West Virginia) to assess POLST use. Staff at hospices reporting POLST use (n = 71) were asked additional questions about their attitudes toward the POLST. Chart reviews were conducted at a subsample of POLST-using programs in Oregon (n = 8), West Virginia (n = 5), and Wisconsin (n = 2).

Results

The POLST is used widely in hospices in Oregon (100%) and West Virginia (85%) but only regionally in Wisconsin (6%). A majority of hospice staff interviewed believe the POLST is useful at preventing unwanted resuscitation (97%) and at initiating conversations about treatment preferences (96%). Preferences for treatment limitations were respected in 98% of cases and no one received unwanted cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intubation, intensive care, or feeding tubes. A majority of hospice patients (78%) with do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders wanted more than the lowest level of treatment in at least one other category such as antibiotics or hospitalization.

Conclusions

The POLST is viewed by hospice personnel as useful, helpful, and reliable. It is effective at ensuring preferences for limitations are honored. When given a choice, most hospice patients want the option for more aggressive treatments in selected situations.

Introduction

Patients who enroll in hospice typically agree to forgo aggressive treatment with the goal of curing disease and instead receive treatments with the goal of preserving comfort.1,2 Many hospice patients have prehospital do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders reflecting a preference for no resuscitation.3 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) status is sometimes overgeneralized to other types of treatments.4–6 However, an exclusive focus on CPR status does not address hospitalizations or preferences for the full range of therapy options. Little is known about hospice patient preferences for life-sustaining interventions, although research suggests that many seriously ill patients do not enroll in hospice because of a desire for treatments that prolong life.7

The first Physicians Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Program was developed in Oregon to overcome the limitations of CPR orders. It is designed to ensure that patient wishes to receive or refuse life-sustaining treatments are honored by converting treatment preferences into medical orders that can be followed by medical personnel regardless of the patient's location. The centerpiece of the program is a brightly colored medical order form that includes orders regarding CPR status, medical interventions, antibiotics, and medically administered nutrition and hydration. It is completed based on conversation(s) with patients and/or their families regarding treatment goals. The POLST Program is now used in several additional states, including California, Idaho, New York, North Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, and West Virginia as well as parts of Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (www.POLST.org). The program name varies by state (e.g., MOLST or Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment in New York and POST or Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment in West Virginia), but all programs based on the POLST share the same key elements. The programs are referred to as POLST Paradigm Programs.

Research supports the efficacy of POLST Paradigm Programs. In a study of 180 Oregon nursing home residents with POLST forms, none received resuscitation against their wishes and only 2% of residents with orders for comfort measures only were hospitalized to extend their lives.8 Other studies have found that medical treatments administered match the POLST form instructions for CPR, antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and feeding tubes more often than previously reported for advance directive forms9 and that orders are consistent with treatment preferences.10

The goal of this descriptive study was to evaluate use of the POLST Paradigm Program by hospice programs, the attitudes of hospice personnel toward POLST Paradigm Programs, the effect of POLST on the use of life-sustaining treatments, and the types of treatments options selected by hospice patients.

Methods

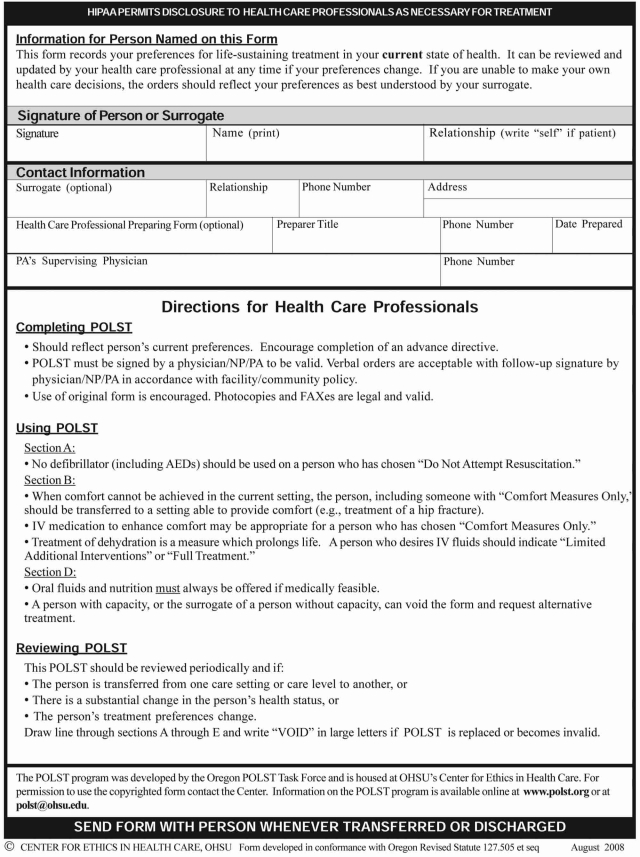

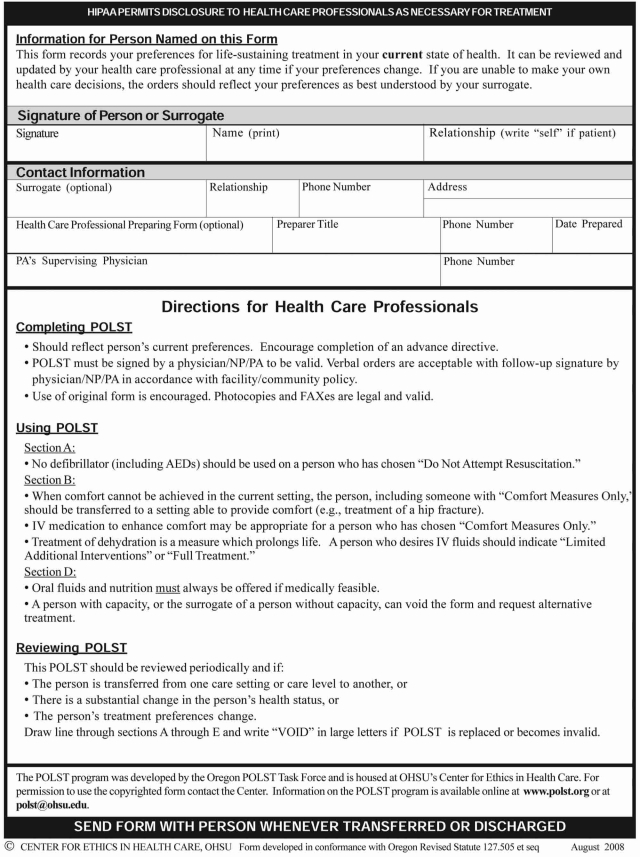

The POLST Paradigm Program

Since this study includes both the Oregon/Wisconsin POLST and the West Virginia POST Programs, it will be referred throughout the text as the PO(L)ST Program and form. The centerpiece of the PO(L)ST Program is the PO(L)ST form, a double-sided, brightly colored form printed on 8½ × 11 inch cardstock. Each state form has slightly different wording, but all share the same basic elements including the ability to document orders regarding treatment preferences.11 The form is divided into five sections:

Section A: CPR orders (Resuscitate or DNR);

Section B: medical interventions orders (Comfort Care Only, Limited Additional Interventions, Full Treatment);

Section C: antibiotics orders (None; Limited Use, Full Treatment);

Section D: medically administered nutrition or hydration orders (None, Defined Trial, Long-term Use);

Section E: who the form was discussed with, summary of medical conditions/basis for the orders, and physician or nurse practitioner's dated signature.

See Figure 1 for a copy of the 2008 Oregon POLST form.

FIG. 1.

2008 Oregon POLST form.

Procedures

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Oregon Health & Science University, West Virginia University, and Gundersen Clinic, Ltd., in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Data were collected between April 2006 and August 2007. The study involved a telephone survey and on-site chart reviews. First, telephone calls were made to all state-recognized hospices in Oregon (n = 50), Wisconsin (n = 68), and West Virginia (n = 21). Participating staff members responsible for discussing and documenting advance care planning were interviewed about their hospice program's use of the PO(L)ST Program. Additional attitudes questions were asked of participants who reported that their program used the PO(L)ST. Next, permission to conduct an onsite chart review of decedents' records was obtained from executive directors at a convenience sample of hospices. Programs that reported using the PO(L)ST for more than half of program patients were eligible for inclusion.

Participants

The telephone survey sample consisted of staff members identified by the hospices as having primary responsibility for advance care planning. One staff member was interviewed per hospice program. Individuals who reported PO(L)ST use at their program were asked additional questions about their own, personal attitudes toward the PO(L)ST Program.

Chart reviews were conducted using the medical records of hospice patients who had died within the previous twelve months at a convenience sample of PO(L)ST-using hospice programs. Twenty-five randomly sampled charts were reviewed at each hospice.

Data collection instruments

The telephone survey tool was designed based on surveys used in previous research studies.12,13 It included questions about their hospice programs' use of forms to document treatment preferences, use of the PO(L)ST Program, the estimated number of patients with PO(L)ST forms (none, less than half, half, more than half, or nearly all/all), and descriptive information about the hospice. Participants at POLST-using programs were asked additional questions asked about their own attitudes toward the PO(L)ST Program.

The chart review data collection tool was developed to track demographic data, preferences and orders for life-sustaining treatments including orders documented on the PO(L)ST form, and the use of life-sustaining treatments such as feeding tubes and hospitalization. Chart reviews covered up to the last 90 days of life following hospice admission.

Results

Telephone survey

Telephone survey participation rates were high but varied by state (Oregon, 100%; West Virginia, 95%; Wisconsin, 93%) resulting in a sample of 133 staff representing 133 hospices. The staff members responsible for advance care planning who participated were executive directors (53%), social workers (28%), nurses (16%), and others such as family services directors or quality improvement coordinators (4%). In many programs, more than one person initiated advance care planning including social services (87%), nurses (74%), physicians/nurse practitioners (26%), executive directors (14%), pastoral care providers (13%), and others such as admissions clerks (3%).

Virtually all participants reported that their hospice used state advance directive forms to document patient wishes for life-sustaining treatments (Oregon, 100%; West Virginia, 100%; Wisconsin, 91%). Use of the Five Wishes program14 was reported by 17% of programs in Wisconsin and West Virginia, where it is legally recognized. All participants reported that their program used a system to document orders for life-sustaining treatments (LSTs) and a majority (53%) reported documenting code status in the medical record. In West Virginia, 95% reported use of the West Virginia DNR Card; in Wisconsin, 84% reported use of the Wisconsin DNR bracelet.

Use of the PO(L)ST Program varied by state (Oregon, 100%; West Virginia, 85%; Wisconsin, 6%). Most PO(L)ST-using hospices had been using the PO(L)ST Program for more than 2 years (80%) and a majority had PO(L)ST forms for more than half of their patients (Oregon, 92%; West Virginia, 73%; Wisconsin, 67%). A majority also reported their hospice typically offers the PO(L)ST form to every patient (84%). Problems relating to use of the PO(L)ST were reported by 51% of participants and about a third of these individuals reported more than one problem. The most commonly reported problems were difficulties understanding and explaining the form (28%); logistical challenges related to obtaining a physician or nurse-practitioner signature (14%); discomfort with issues raised by the form (12%); transfer across settings (10%); and inadequate provider education (10%). Other problems mentioned by fewer than 10% of participants included complaints that the PO(L)ST form was not honored and there were multiple versions of the form due to periodic revisions.

Participants employed by PO(L)ST-using hospices (n = 71) were also asked additional questions regarding their individual, personal attitudes toward the PO(L)ST Program. Most participants (97%) believed the PO(L)ST form was useful in preventing unwanted resuscitations by emergency medicine personnel and a similarly large percentage (96%) found it useful in initiating conversations about treatment preferences. Only 4% of participants indicated that they believed a PO(L)ST form made treating patients more complicated. See Table 1 for a complete description of hospice staff attitudes toward the PO(L)ST Program.

Table 1.

Hospice Staff Attitudes Toward the PO(L)ST Program

| |

n = 71 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Agree or strongly agree | Neutral | Disagree or strongly disagree |

| The PO(L)ST for is useful in preventing unwanted resuscitation by EMS. | 97% | 3% | — |

| The PO(L)ST form serves as a helpful mechanism for initiating a conversation about treatment preferences. | 96% | 3% | 1% |

| The PO(L)ST form helps ensure patient treatment preferences are honored. | 94% | — | 6% |

| The PO(L)ST form reliably express patient treatment preferences. | 93% | 6% | 1% |

| I feel more comfortable knowing what to do when a PO(L)ST form is available. | 93% | 7% | — |

| The PO(L)ST form provides clear instructions about a patient's treatment preferences. | 92% | 4% | 4% |

| The PO(L)ST form is useful in preventing unwanted hospitalization. | 87% | 9% | 4% |

| The PO(L)ST form is not working in my community. | 7% | 4% | 89% |

| Having a PO(L)ST form makes treating patients more complicated. | 4% | 4% | 92% |

PO(L)ST refers to both the Oregon/Wisconsin Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) and West Virginia Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST). Response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The attitudes survey was administered only to participants who reported they were employed at hospice programs where the PO(L)ST Program is in use.

Chart review

Chart reviews were conducted at 15 PO(L)ST-using hospice programs: 8 in Oregon, 5 in West Virginia, and 2 in Wisconsin. The number of programs sampled in each state varied due to differences in PO(L)ST Program use and logistical issues. Every program approached agreed to participate. A total of 373 decedent medical chart reviews were conducted; 275 charts contained PO(L)ST forms, as not all patients within PO(L)ST-using hospice programs have a PO(L)ST form. Demographic and descriptive information about these decedents is contained in Table 2. A majority of the forms (94%) contained a physician or nurse-practitioner signature, which is necessary in order for the form to be valid.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Deceased Hospice Patients

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| State | |

| Oregon | 200 (54) |

| West Virginia | 123 (33) |

| Wisconsin | 50 (13) |

| Agea | |

| 18 and under | 1 (0.3) |

| 19–64 | 47 (12.6) |

| 65 and older | 325 (87.1) |

| Femalea | 212 (57) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |

| White, not of Hispanic origin | 314 (84.2) |

| African American, not of Hispanic origin | 1 (0.3) |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.8) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | — |

| Asian | 2 (0.5) |

| Other (mixed race) | 2 (0.5) |

| Not available | 50 (13.4) |

| Place of deatha | |

| Private home | 164 (44.0) |

| Hospital | 21 (5.6) |

| In-patient hospice | 2 (0.5) |

| Foster home/residential care/assisted living | 54 (14.5) |

| Nursing facility | 110 (29.5) |

| Other | 11 (2.9) |

| Not available | 11 (2.9) |

| Patient Cared For By:a (more than one could be checked) | |

| Spouse/partner | 114 (31) |

| Other family member | 251 (67) |

| Paid caregiver | 162 (43) |

| Friend | 13 (4) |

| Other | 2 (0.5) |

| Primary diagnosisa | |

| Cancer | 149 (40) |

| Heart Related Disease | 53 (14) |

| Respiratory Related Disease | 37 (10) |

| Dementia | 30 (8) |

| Neurologic disease | 12 (3) |

| Stroke | 11 (3) |

| Renal Disease/failure | 11 (3) |

| Liver Disease/failure | 6 (2) |

| Other | 63 (17) |

| Mean length of stay in hospice in weeksa | 11 |

| PO(L)ST in chartb | 275 (74) |

| Patient or surrogate signature on PO(L)STc | |

| Overall | 176 (82) |

| Oregon | 93 (79) |

| West Virginia | 79 (99) |

| Wisconsin | 4 (24) |

| Physician or Nurse Practitioner signature on PO(L)STc | 256 (94) |

| Orders Discussed With section completed on PO(L)STc | 251 (91) |

| Person(s) PO(L)ST Discussed Withc | |

| Patient | 73 (29) |

| Health Care Surrogate | 95 (38) |

| Family Member | 16 (6) |

| Patient and Health Care Surrogate Together | 40 (16) |

| Patient and family member | 20 (8) |

| Health care surrogate and family members | 7 (3) |

Note: PO(L)ST refers to both the Oregon/Wisconsin Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) and West Virginia Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST). Total n = 373; with PO(L)ST n = 275.

There were no statistically significant differences between participants with PO(L)ST forms and those without, so information about these groups is presented together.

Charts were randomly sampled and not all charts contained PO(L)ST forms.

Patients with PO(L)ST forms only.

A binomial test indicated that patients with PO(L)ST forms were significantly more likely to have orders regarding LSTs than patients without PO(L)ST forms (100% versus 36%; p < 0.001). Logistic regression analyses indicated that patient variables (age, gender, diagnosis of cancer versus noncancer, and length of hospice stay in weeks) were not predictive of having a valid PO(L)ST form.

A majority of patients (99%) with PO(L)ST forms had DNR orders in Section A. Most (78%) contained orders for more than the lowest level of treatment in at least one other category (Table 3). In Section B, 20% reflected orders for limited additional medical interventions or full treatment. In Section C, 77% reflected orders for antibiotic treatments. In Section D, 11% reflected orders for either a short-term trial or long-term placement of feeding tubes and/or intravenous fluids. A logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether any patient variables (age, gender, diagnosis, length of stay in weeks) were predictive of the orders marked in Section A, resuscitation (yes or no); Section B, medical interventions (none versus some); Section C, antibiotics (none versus some); and Section D, feeding tube use (none versus some). Only length of stay was significantly predictive of orders for medical interventions. Patients with longer lengths of stay were more likely to have orders for limited or full medical interventions than patients with shorter lengths of stay (odds ratio [OR] = 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.01–1.09).

Table 3.

Orders on Hospice Patients' Valid PO(L)ST Formsa

| Treatment category | PO(L)STs marked resuscitate (n = 3) n (%) | PO(L)STs marked do not resuscitate (n = 253) n (%) | All valid PO(L)STs (n = 256) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Section B: Medical Interventions | |||

| Comfort Care Only | (1) 33% | (200) 79% | (201) 79% |

| Limited/additional interventions | (1) 33% | (51) 20% | (52) 20% |

| Full treatment | (1) 33% | (1) <1% | (2) 1% |

| Section C: Antibiotics | |||

| No antibiotics | — | (56) 23% | (56) 23% |

| No invasive antibiotics | — | (83) 34% | (83) 33% |

| Full treatment | (3) 100% | (106) 43% | (109) 44% |

| Section D: Medically Administered Fluids and Nutritionb | |||

| No feeding tube/intravenous fluids | (2) 67% | (215) 89% | (217) 88% |

| Defined trial only | (1) 33% | (22) 9% | (23) 9% |

| Long-term feeding tube/intravenous fluids | — | (6) 2% | (6) 3% |

Note: PO(L)ST refers to both the Oregon/Wisconsin Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) and West Virginia Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST).

Valid PO(L)ST forms are those with a clinician signature.

Medically administered fluids removed from this section and relocated to medical interventions on 2007 Oregon POLST form.

Life-sustaining treatments

A minority of patients with valid PO(L)ST forms received treatments that were potentially life-sustaining including non-topical antibiotics (25%), hospitalization (13%), intravenous fluids (3%), chemotherapy (2%), surgery (1%), feeding tubes (1%), and transfusions (< 1%). None of the patients with PO(L)ST forms in the sample received CPR. Ninety-nine percent of the time the withholding of CPR was in accordance with the PO(L)ST order. The chart review did not yield information about why three patients with orders for resuscitation did not receive CPR. A series of logistic regressions were performed to determine whether PO(L)ST orders for none versus some treatments were predictive of treatments provided. Patients with orders for comfort care only (Section B) were significantly less likely to experience hospitalization, intravenous fluids, chemotherapy, surgery, and transfusions, than patients with orders for limited or full medical interventions (OR = 3.74, 95% CI = 1.81–7.72). Orders regarding antibiotics (Section C) were not predictive of the use of antibiotics. Cell sizes were too small to analyze data regarding the use of feeding tubes (Section D).

To evaluate whether PO(L)ST orders were being followed, situations in which use of LSTs that appeared to be inconsistent with patient's PO(L)ST form orders were identified. Treatments provided with documentation that the intent was to enhance comfort were not counted as treatment deviations. Eight treatment deviations were identified, representing 3% of the 255 patients with signed, valid PO(L)ST forms. Five patients potentially received more aggressive treatment than indicated on the PO(L)ST form; 3 potentially received less aggressive treatment than indicated on the PO(L)ST. In the 5 cases of apparent overtreatment, the deviations occurred in patients with infections. Four received antibiotics and 1 was hospitalized despite orders for comfort care only and no antibiotics. In the 3 cases of apparent undertreatment, patients with full code orders were not resuscitated.

Discussion

The PO(L)ST Paradigm Program was developed to ensure that patients' wishes regarding a range of end-of-life treatments would be identified and respected. This is the first study reporting the outcomes of the PO(L)ST Paradigm Program in the care of hospice patients. Findings suggest that hospice personnel believe the PO(L)ST Program is a helpful tool for initiating end-of-life conversations, that it reliably expresses patients' treatment preferences, and that it helps ensure treatment preferences are honored. Hospice patients with PO(L)ST forms have significantly more orders regarding life-sustaining treatment preferences than patients without PO(L)ST forms. Resuscitation status alone does not predict preferences for the level of aggressiveness of other medical interventions or for the use of antibiotics in hospice patients. Preferences for treatment limitations on the PO(L)ST were respected in nearly all cases.

Approximately 20% of patients with DNR orders also had orders for hospitalization when otherwise medically indicated and 77% had orders for the use of antibiotics. This suggests that a focus on resuscitation status does indeed appear to falsely dichotomize and oversimplify treatment choices near the end of life.15 This finding supports the use of the PO(L)ST Program in the hospice setting as individualization of care plans is a requirement under most hospice benefit plans as well as Medicare and Medicaid.16 This flexibility appears to be valuable in the hospice setting, where some may mistakenly assume a universal preference for the least aggressive level of treatment. Study results are also consistent with a study of nursing home residents that found a majority (78%) of residents with PO(L)ST forms indicating DNR orders requested some other type of life-extending treatment such as a hospitalization or antibiotics.11 Hence, resuscitation preference alone should not be used to infer treatment preferences for anything other than resuscitation.

It is possible that PO(L)ST forms contained orders for more than the lowest level of treatment indicated with the goal of enhancing comfort rather than extending life. However, the PO(L)ST form directs providers to use more aggressive treatment to ensure comfort when necessary, regardless of PO(L)ST form orders. Writing orders for more aggressive treatment just to ensure that comfort is provided should not be necessary. For example, a patient with comfort care only orders in Section B should usually be sent to the hospital to stabilize a hip fracture or to address uncontrolled pain.

This study is also remarkable in the extent to which orders for treatment limitations were honored. In 250 of 255 (98%) cases, patients' preferences for treatment limitations were respected. No patient received unwanted CPR, ventilator support, ICU admission, or feeding tubes. This compliance with patients' wishes for treatment limitations exceeds most previously reported studies of patients with advance directives17 although it is consistent with previous research on the PO(L)ST.13 Deviations from PO(L)ST orders to limit treatment were rare. Five involved the potential over-treatment of patients with infections. It is likely that these treatments were intended to enhance comfort,18 although the intent was not specified in the chart. Three involved the potential under-treatment in patients with Full Code orders who were apparently not resuscitated. There was no documentation in the medical records to explain why resuscitation was not provided.

Limitations

Telephone survey data about advance care planning and use of the PO(L)ST Program may be limited by the telephone survey respondents' familiarity with hospice operations. Second, the attitudes survey was administered only to hospice personnel at PO(L)ST-using programs in three states. It is possible that the attitudes of personnel at programs that do not use the PO(L)ST are less positive, however these individuals were excluded due to concerns that staff at non-PO(L)ST using programs would not have sufficient familiarity with the program to answer the attitude survey questions. Furthermore, these responses are only representative of the participant and may not be reflective of the attitudes of their coworkers. Third, the chart review represents a nonrandom convenience sample of patients treated in only 16% of hospices in Oregon, 24% of hospices in West Virginia, and 3% of hospices in Wisconsin. It is unclear how representative these findings are of the general hospice population. Finally, although the number of identified treatment deviations was small, the chart review methodology made it difficult to detect situations in which more aggressive treatment was indicated but not provided. Future prospective research should focus on verifying that orders and treatments match patient preferences as well as exploring whether the PO(L)ST form is fully understood by patients and family members.

Conclusions

The PO(L)ST Paradigm Program is well-regarded by hospice staff and widely used in Oregon and West Virginia. Findings confirm that traditional code status orders do not reflect the range of treatments preferred by hospice patients: DNR does not mean “do not treat.” When given a choice, most hospice patients want the option for more aggressive treatments in selected situations. The PO(L)ST Program allows for greater individualization of advance care planning than code status alone. It also appears to be effective at limiting unwanted treatments in the hospice setting. Overall, study findings confirm the benefit of PO(L)ST programs for hospice patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Antons, L.P.N., Mary Cummins Collins, R.D., Shoshana Maxwell, Sara Posey, M.P.H., Georgie Sawyer, R.N., and Amanda Schneider, R.N., for their assistance with data collection. We thank Lois Miller, R.N., Ph.D., for her contributions to the initial conceptualization of this project. We are deeply grateful for the cooperation of hospice programs and personnel who participated in this study. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (Grant R01 NR009784) and by a private donation to the OHSU Center for Ethics in Health Care.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lorenz KA. Asch SM. Rosenfeld KE. Liu H. Ettner SL. Hospice admission practices; Where does hospice fit in the continuum of care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:725–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA. Katz IT. Letting go of the rope—Aggressive treatment, hospice care, and open access. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:324–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cintron A. Hamel MB. Davis R. Burns R. Phillips RS. McCarthy EP. Hospitalization of hospice patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:757–768. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach MC. Morrison RS. The effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on physician decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2057–2061. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtzman J. Pheley AM. Lurie N. Changes in orders limiting care and the use of less aggressive care in nursing home population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zweig SC. Kruse RL. Binder EF. Szafara KL. Mehr DR. Effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on hospitalization of nursing home residents evaluated for lower respiratory infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casarett D. Van Ness PH. O'Leary JR. Fried TR. Are patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment really a barrier to hospice enrollment for older adults with serious illness? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolle SW. Tilden VT. Nelson CA. Dunn PM. A prospective study of the efficacy of the PO(L)ST: Physician Order Form for Life-Sustaining Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1097–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MA. Brummel-Smith K. Meyer J. Drew N. London MR. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): Outcomes in a PACE program. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1219–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers JL. Moore C. McGrory A. Sparr J. Ahern M. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form: Honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30:37–46. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20040901-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickman SE. Hammes BJ. Tolle SW. Moss AH. A viable alternative to traditional living wills. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;30:4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickman SE. Tolle ST. Brummel-Smith K. Carley MM. Use of the POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) program in Oregon: Beyond resuscitation status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1424–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt TA. Hickman SE. Tolle SW. Brooks HS. The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment program: Oregon emergency medical technicians' practical experiences and attitudes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1430–1434. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aging with Dignity. Five Wishes. www.agingwithdignity.org/5wishes.html. [May 13;2008 ]. www.agingwithdignity.org/5wishes.html

- 15.Happ MB. Capezuti E. Strumpf N. Wagner L. Cunningham S. Evans L. Maislin G. Advance care planning and end-of-life care for hospitalized nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:829–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medicare Conditions of Participation in Hospice Care. 2008;42 CFR § 418 418.56[B]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Mansfield J. Lipson S. Which advance directive matters? Res Aging. 2008;30:74–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinbolt RE. Shenk AM. White PH. Navari RM. Symptomatic treatment of infections in patients with advanced cancer receiving hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]