Abstract

Regeneration is widespread throughout the animal kingdom, but our molecular understanding of this process in adult animals remains poorly understood. Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays crucial roles throughout animal life from early development to adulthood. In intact and regenerating planarians, the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling functions to maintain and specify anterior/posterior (A/P) identity. Here, we explore the expression kinetics and RNAi phenotypes for secreted members of the Wnt signaling pathway in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Smed-wnt and sFRP expression during regeneration is surprisingly dynamic and reveals fundamental aspects of planarian biology that have been previously unappreciated. We show that after amputation, a wounding response precedes rapid reorganization of the A/P axis. Furthermore, cells throughout the body plan can mount this response and reassess their new A/P location in the complete absence of stem cells. While initial stages of the amputation response are stem cell independent, tissue remodeling and the integration of new A/P address with anatomy are stem cell dependent. We also show that WNT5 functions in a reciprocal manner with SLIT to pattern the planarian mediolateral axis, while WNT11-2 patterns the posterior midline. Moreover, we perform an extensive phylogenetic analysis on the Smed-wnt genes using a method that combines and integrates both sequence and structural alignments, enabling us to place all nine genes into Wnt subfamilies for the first time.

Introduction

Most animal phyla contain species that regenerate tissues lost to injury with various degrees of success and some of these animals display extraordinary regenerative capacities (Brockes and Kumar, 2008; Holstein, 2008; Poss et al., 2002; Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004). Despite sharing a similar genetic toolkit with regeneration-competent animals, mammalian regeneration pales by comparison. Why such disparities in regenerative abilities exist across metazoan phyla is presently unknown.

The interrogation of animal development in recent decades has revealed a deep conservation of intercellular signaling pathways that allow cells to communicate and coordinate embryonic processes such as axis formation, cell division, differentiation, organogenesis, and tissue patterning (Pires-daSilva and Sommer, 2003). Some of these pathways are re-activated during regeneration, but little is known about how signaling is coordinated during a regenerative response or whether differences in regenerative abilities stem from differences in signaling pathway recruitment (Galliot and Ghila, 2010; Gurley and Sánchez Alvarado, 2008; Stoick-Cooper et al., 2007a).

Planarians provide an attractive model system to study the role of cell signaling during regeneration because their genome encodes major signaling pathway components (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008; Rink et al., 2009; Yazawa et al., 2009) and because they display an incredible ability to tolerate a wide variety of amputations (Morgan, 1898; Morgan, 1900). Even small fragments removed from the flank of the body can regenerate entire worms of proper proportion (Randolph, 1897). This remarkable plasticity relies on the presence of adult somatic stem cells that are broadly distributed throughout the body plan, divide to constantly replenish cells lost to tissue turnover, and give rise to all tissues including the nervous, gastrovascular, muscular, and excretory systems (Newmark and Sánchez Alvarado, 2000; Pellettieri and Sánchez Alvarado, 2007; Reddien and Sánchez Alvarado, 2004)

Planarian stem cells located anywhere along the anterior/posterior (A/P) axis have the intrinsic ability to regenerate a head or tail (Morgan, 1904). This choice depends upon the cell’s position in the freshly amputated fragment (Morgan, 1898). Thus, communication between stem cells and the surrounding pre-existing tissue is critical for proper fate choice. However, the extent to which differentiated cells respond to amputation or to their new relative location independent of stem cells is poorly understood. It was recently shown that normal amputation-induced organism-wide apoptotic responses still occur in the absence of stem cells (Pellettieri et al., 2009), but we have only begun to understand which signaling pathways are involved in the initial phases of regeneration and how these pathways are coordinated to facilitate a regenerative response.

We and others have demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential to guide proper regeneration in planarians (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). Wnt ligands define a deeply conserved family of secreted glycoproteins that have diverse effects on cell function through β-catenin dependent or independent pathways. Depending on context, Wnts influence cell proliferation, fate choice, migration, survival, and even maintenance of multipotency (Clevers, 2006; van Amerongen and Nusse, 2009; Veeman et al., 2003). In adult humans, Wnt pathway misregulation can lead to disease and cancer (Clevers, 2006; Logan and Nusse, 2004; Moon et al., 2004).

In planarians, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a critical molecular switch that controls the choice to regenerate a head or tail. Specifically, increased Wnt/β-catenin activity specifies posterior fate and elicits tail regeneration (Gurley et al., 2008; Rink et al., 2009; Yazawa et al., 2009), while decreased Wnt/β-catenin activity specifies anterior fate and triggers head regeneration (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). Interestingly, silencing Smed-βcatenin-1 in intact planarians causes widespread anteriorization and ectopic head formation (Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008), suggesting that as in humans, β-catenin signaling is active and highly regulated in intact adult planarians.

Consistent with a role for β-catenin in specifying posterior fate, numerous wnt genes are expressed in the posterior end of intact planarians (Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). Likewise, two of the three secreted frizzled related proteins (sFRPs), which are frequently assumed to be inhibitors of Wnt signaling (Mii and Taira, 2009), display anterior-specific expression (Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). After amputation, small fragments such as tails radically reorganize the A/P axis and coordinately modify wnt and sFRP expression to reestablish the proper adult patterns. It is unknown to what extent this process depends on the regeneration of new tissue. Two previous reports suggested that pre-existing differentiated tissues can respond to amputation and reorganize the A/P axis in the absence of stem cells (Ogawa et al., 2002; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). However, these analyses were both limited to the expression of one or two genes and did not address how newly generated tissues integrate with pre-existing tissues during later stages of regeneration and tissue remodeling.

To gain further insight into the regeneration response of planarians, we characterized the phenotypes resulting from wnt gene silencing, and explored the expression of eight wnt and three sFRP genes during regeneration. Our expression studies provide valuable insights into the dynamic response of planarian tissues to amputation and to the interplay between pre-existing tissues and stem cells during regeneration. We show that cells throughout the animal assess their new position along the A/P axis in the complete absence of stem cells. However, both the remodeling of existing organ systems and the proper integration of A/P location with the anatomy is stem cell dependent. Additionally, our extensive phylogenetic analyses placed all nine Smed-wnt genes into Wnt subfamilies for the first time. Finally, we report on phenotypes resulting from Smed-wnt5(RNAi) and Smed-wnt11-2(RNAi). WNT5 functions reciprocally with SLIT to organize the mediolateral axis, while WNT11-2 patterns the tail midline.

Materials and methods

Planarian maintenance

The CIW4 clonal line of Schmidtea mediterranea was maintained as previously described (Cebrià and Newmark, 2005; Sánchez Alvarado et al., 2002). 1–2 week starved animals were used for all experiments.

Gene sequences

Human and Drosophila protein sequences were used to find planarian homologs of secreted Frizzled-related proteins: Smed-sFRP-2 (Gurley et al., 2008), GenBank accession number HM751831; and Smed-sFRP-3 (Gurley et al., 2008), GenBank accession number HM751832, from the S. mediterranea genome database (smedgd.neuro.utah.edu) (Robb et al., 2008) via BLAST (Fig. S1). Planarian homologs were then used for reciprocal BLAST against the human refseq database to verify homology. Protein domains were predicted using InterPro (Hunter et al., 2009). All sequences were cloned from cDNA obtained from an 8-day regeneration series as described (Gurley et al., 2008). Complete sequences and accession numbers have been previously reported for all nine Smed-wnt genes, in addition to sFRP-1 (Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008), porcn-1, PC-2 (Gurley et al., 2008), and slit (Cebrià et al., 2007).

Phylogenetic methods

Sequence alignments

The Wnt sequences of the planarian S. mediterranea were aligned using the integrated alignment approach that combines sequence and structural alignment (Lengfeld et al., 2009).

Phylogenetic trees

Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian methods using the WAG model (Whelan and Goldman, 2001) assuming rate homogeneity or assuming rate heterogeneity with 4 discrete Gamma rate categories (Yang, 1993). Missing parameters are estimated from the data and option set to default settings if not otherwise stated. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed using IQPNNI 3.3 (Minh et al., 2005; Vinh le and Von Haeseler, 2004) applying the stopping rule after a minimum of 200 iterations and a maximum of 2500. ML bootstrap trees/values from 100 bootstrap trees were computed with the same parameters but using the bootstrap option (-bs) of IQPNNI 3.3 and summarized using a relative majority consensus (Schmidt, 2003) as implemented in TREE-PUZZLE 5.3 (Schmidt and von Haeseler, 2007). Puzzling trees and puzzle support values have been constructed with TREE-PUZZLE 5.3. For Quartet Puzzling (QP) and/or SuperQP trees puzzling trees and puzzle support values have been constructed with TREE-PUZZLE 5.3 (Schmidt and von Haeseler, 2007) applying either Quartet Puzzling voting scheme (QP, cf.) (Strimmer et al., 1997; Strimmer and Von Haeseler, 1996) or the Superquartet Puzzling scheme (SuperQP) (Schmidt, 2003) summarizing with a relative majority consensus (Schmidt, 2003). Bayesian trees were computed using MrBayes (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) performing four runs with two chains running for 30 Mio generations each. Every 200th tree was sampled from the cold chains after a burn-in of 5 Mio generations. The results were checked for convergence artifacts with Tracer 1.4.1 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/).

RNAi

RNAi feedings were performed as described previously (Gurley et al., 2008) with the following modifications: Soft-serve RNAi food for all genes was prepared 2–4 times more concentrated. Smed-wnt(RNAi) animals were fed 4–9 times every 2–3 days prior to a single amputation. Long-term Smed-wnt(RNAi) intact animals were fed RNAi food 1–2 times per week until the indicated fixation day. For Fig. S18, APC(RNAi) animals were fed 3–4 times and βcatenin(RNAi) animals were fed twice before amputation. For all RNAi experiments, animals were cut 3–5 days after the last feed.

Gamma irradiation

100 Gray (10,000 rads) of γ-irradiation was delivered to animals as previously described (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Animals were then amputated 3–5 days after irradiation as specified in the text. These are time points when markers for proliferation, neoblasts, and immediate division progeny have already been lost (Fig. S16A)(Eisenhoffer et al., 2008).

In situ hybridization and immunostaining

Fluorescent and colorimetric in situ hybridizations were performed as previously described (Pearson et al., 2009). Anti-α-Tubulin AB-2 mouse monoclonal antibody from Fisher Scientific was used at 1:300 to detect the cephalic ganglia, nerve cords, and pharynx (Robb and Sánchez Alvarado, 2002). VC-1 mouse monoclonal antibody, a kind gift from Dr. Kiyokazu Agata, was used at 1:10,000 to detect photoreceptors and the visual axons (Agata et al., 1998). Anti-phospho-histone H3 (ser10) MC463 rabbit monoclonal antibody from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions was used at 1:300 to detect mitotic activity (Robb and Sánchez Alvarado, 2002).

Image capture and processing

Images of live animals and whole-mount in situ hybridization in which NBT-BCIP was used as part of the development procedure were captured on a Zeiss Lumar V12 stereomicroscope using an Axiocam HRc camera. For overlays of NBT/BCIP signal with fluorescent signal in the same animal, the NBT/BCIP image was inverted in Adobe Photoshop and transferred into an appropriate fluorescent channel. Linear adjustments such as brightness and contrast were globally adjusted for each image before overlay. All fluorescent images in which no colorimetric development was employed were either mounted in glycerol or BABB (1 volume benzyl alcohol: 2 volumes benzyl benzoate). Specimens were imaged on a Zeiss LSM510-Live Laser Scanning Microscope using the Zeiss LSM Image Browser Software for image acquisition. The images were subsequently exported as TIFs and modified in Adobe Photoshop as detailed above.

Results and discussion

Planarian WNT phylogeny

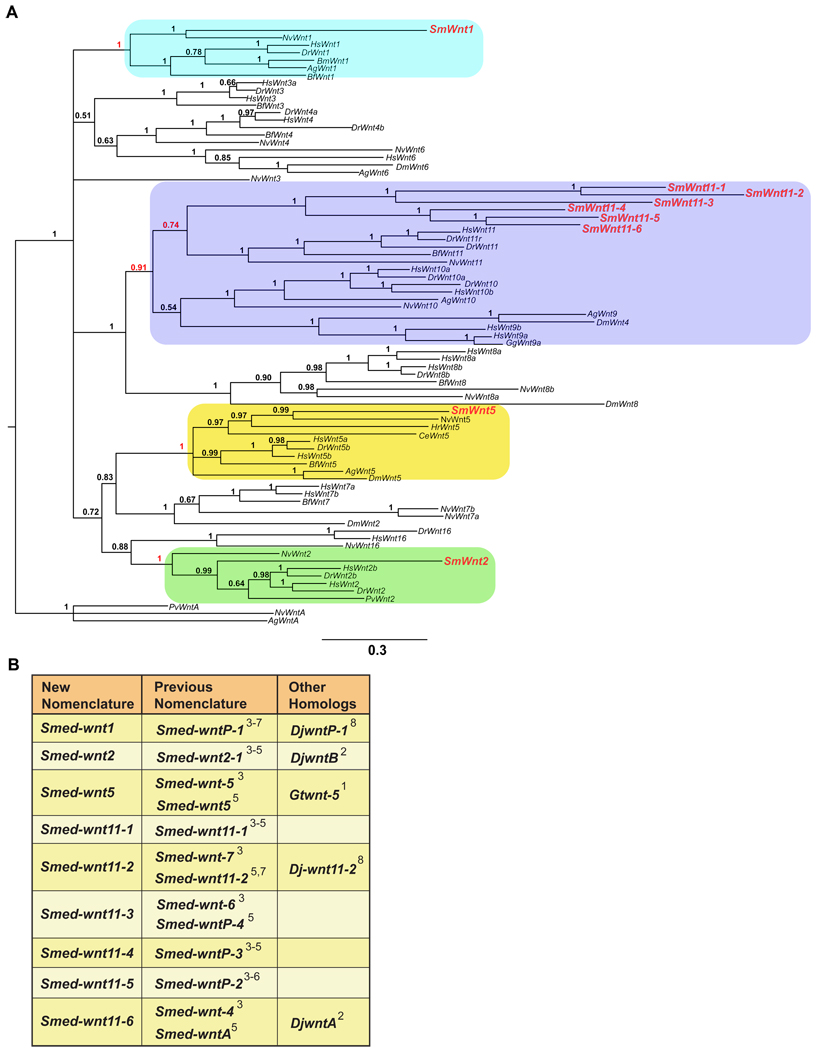

Previous genome searches (smedgd.neuro.utah.edu) and cloning revealed the presence of nine planarian wnt genes (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). Phylogenetic analyses determined that Smed-wnt5 could confidently be placed as an ortholog of Wnt-5 (Adell et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2008), while Smed-wnt2, Smed-wnt11-1, and Smed-wnt11-2 clustered with Wnt-2 and -11 subfamilies, respectively, but with low confidence (Adell et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). To determine the most likely evolutionary relationship between planarian and metazoan Wnt genes, we performed extensive phylogenetic analyses utilizing a method that combines and integrates sequence and structural alignments. Similar analyses were recently used to place Hydra Wnt genes into their appropriate subfamilies (Lengfeld et al., 2009). The data from these studies are summarized in Figure 1 (see Table S1 and supplementary figures S2–14 for supporting phylogenetic trees).

Fig. 1.

(A) Phylogenetic tree using Bayesian inference of Wnt proteins. Sequences were selected from Aedes aegyptii (Ag), Bombyx mori (Bm), Branchiostoma floridae (Bf), Caenorhabditis elegans (Ce), Danio rerio (Dr), Drosophila melanogaster (Dm), Gallus gallus (Gg), Halocynthia roretzi (Hr), Homo sapiens (Hs), Nematostella vectensis (Nv), and Patella vulgaris (Pv), and Schmidtea mediterranea (Sm) (All available Wnt genes). The numbers at the branches indicate the posterior probabilities computed by MrBayes for the respective nodes. Red numbers indicate support of the rooting branch of the subfamily containing the respective Smed-wnt gene. (B) Classification of the S. med. wnt genes based on phylogenies reconstructed with Bayesian analysis (Mrbayes) (Huelsenbeck et al., 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003), Maximum Likelihood (IQPNNI, best tree and bootstrapped) (Minh et al., 2005; Vinh le and Von Haeseler, 2004), quartet puzzling (QP) (Schmidt and von Haeseler, 2007), and Superquartet Puzzling (SuperQP) (Schmidt and von Haeseler, 2007). See Figures S2–14 for all trees and Table S1 for a summary of the phylogenetic data. 1-(Marsal et al., 2003) 2-(Kobayashi et al., 2007) 3-(Gurley et al., 2008) 4-(Petersen and Reddien, 2008) 5-(Adell et al., 2009) 6-(Petersen and Reddien, 2009) 7-(Rink et al., 2009) 8-(Yazawa et al., 2009).

Of the nine Smed-wnt genes, three encode orthologs of the subfamilies Wnt-1, -2, and -5 found in mammalian and cnidarian genomes. The remaining six wnt genes were found to encode S. mediterranea orthologs of Wnt-11. Hence, we have renamed the planarian wnt genes accordingly: wnt1 (was wntP-1), wnt2 (was wnt2-1), wnt5 (same), wnt11-1 (same), wnt11-2 (same), wnt11-3 (was wntP-4), wnt11-4 (was wntP-3), wnt11-5 (was wntP-2), and wnt11-6 (was wntA) (Fig. 1B). The Smed-wnt11 genes always clustered together with the Wnt-11 of cnidarians and bilaterians, suggesting that they represent planarian specific duplications, although the support values were very low. Notably, the members of the Smed-wnt11 cluster formed two subtrees (wnt11-1,2,3 and wnt11-4,5,6). Reducing the complexity of the subtrees to two representatives (Smed-wnt11-1 and Smed-wnt11-4, respectively) resulted in similar tree topologies and clustering (Fig. S2–14, Table S1).

The number of Wnt genes in deuterostomes ranges from 11 to 19 (Logan and Nusse, 2004; Nelson and Nusse, 2004), which cluster into 12 Wnt gene subfamilies. In contrast, protostome genomes contain 4 to 9 Wnt genes (Lengfeld et al., 2009). Our phylogenetic analysis on S. mediterranea wnt genes supports this observation. The nine Smed-wnt genes clustered into only four subfamilies (Wnt-1, -2, -5, and -11). The existence of the wnt1 subfamily was highly supported (Fig. 1A), but we could not identify orthologs of Wnt-3, -4, -6, -8, -9, -10, -16 or -A. Among protostomes, there is a high degree of variability as to whether a given genome contains members of the Wnt-2 through -11 families, while no protostome has been shown to contain a Wnt-16 family member. Interestingly, planarians and other lophotrochozoans contain a Wnt-2 ortholog, while no ecdysozoan has yet been shown to contain a member of this subfamily. Although the phylogenetic methods do not show very high support values for the planarian wnt11 genes, confidence in the classifications is based on the fact that the different methods tested (Fig. S2–14, Table S1) do not contradict the classification shown in Figure 1. Our analysis indicates that the Smed-wnt11-1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6 genes likely represent planarian specific duplications of an ancient wnt11 homolog. If true, this would represent the largest duplication of a Wnt family member from any animal studied to date. An alternative explanation could be that these wnt genes are members of a larger Wnt 9/10/11 cluster (Fig. 1A) (Lengfeld et al., 2009) that is poorly resolved in planarians, but could be resolved with a larger dataset containing more planarian species. The lower complexity of the protostome Wnt gene repertoire compared to deuterostomes and cnidarians suggests that a significant loss of family members took place during the evolution of the protostomes (Kusserow et al., 2005; Lengfeld et al., 2009).

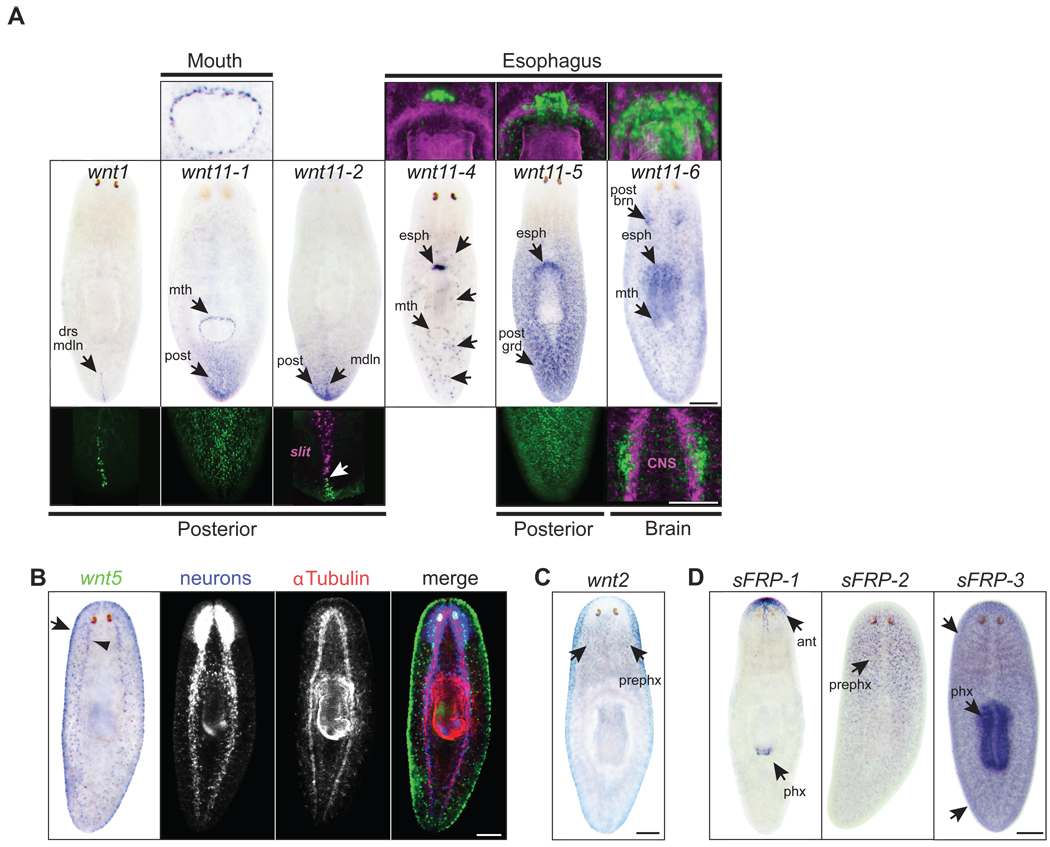

Complex pattern of wnt and sFRP expression in intact planarians

To investigate the roles of genes encoding secreted members of the Wnt signaling pathway, we first determined their expression patterns in intact adult planarians using an optimized in situ hybridization protocol (Pearson et al., 2009). This protocol enabled the visualization of additional, previously unreported patterns. Eight of nine planarian wnt genes were expressed in discrete cells distributed throughout the adult body plan and most exhibited more than one domain of expression (Fig. 2A–C) (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). Five wnt genes showed an overall posterior bias in expression (wnt1, wnt11-1, wnt11-2, wnt11-4, and wnt11-5; Fig. 2A). The three secreted Frizzled Related Proteins (sFRPs) were also expressed in discrete cells throughout intact adults (Fig. 2D). Two sFRP genes exhibited a clear anterior bias (sFRP-1, sFRP-2), while the third (sFRP-3) exhibited a slight anterior bias during development of the in situ signal, but was also strongly expressed along the entire A/P axis and in the pharynx (Fig. 2D). Combined, the wnt and sFRP expression patterns suggest the potential presence of a complex gradient (high posterior to low anterior) of β-catenin activity in intact animals (Gurley et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008). Although direct evidence for such a gradient is presently lacking, the observed formation of multiple anterior domains and ectopic heads in uninjured βcatenin-1(RNAi) animals (Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008) is consistent with the idea that a gradient of β-catenin activity is constantly maintained in intact planarians.

Fig. 2.

wnt and sFRP expression patterns in intact animals. (A) Middle panels: NBT-BCIP in situs in intact animals. Insets for fluorescent in situs are shown for regions of interest in upper and lower panels (green). wnt1: (lower) stripe of cells along the posterior dorsal midline (drs mdln). wnt11-1: (upper) mouth (mth). (lower) posterior gradient (post). wnt11-2: superficial expression around the dorsal and ventral domains of the tail. (lower) midline stripe that abuts the posterior tip of slit expression (magenta, arrow) and is embedded with respect to the D/V axis. wnt11-4: (upper) cluster of cells near the esophagus (esph). Esophagus/pharynx; α-Tubulin antibody (magenta). Also expressed in unidentified distinct cells (unlabeled black arrows) throughout the body plan with a slight posterior bias. wnt11-5: (upper) cluster of cells near the esophagus (esph). Esophagus/pharynx; α-Tubulin antibody (magenta). (lower) posterior-to-anterior gradient (post grad). wnt11-6: (upper) near the esophagus (esph) in a cluster of cells that surround cells expressing wnt11-5 and wnt11-4. Esophagus/pharynx; α-Tubulin antibody (magenta). (lower) posterior brain (post brn). Brain and axons; α-Tubulin antibody (magenta). Also expressed at low levels throughout the body plan and in the mouth (mth). (B) wnt5 was expressed ventrally along the body edge (dorsal/ventral boundary; arrow) and in the region lateral to the ventral nerve cords (arrowhead). Specimens were developed with NBT-BCIP for wnt5 (false-colored in green) and FITC-tyramide for prohormone convertase (PC-2, neuronal cell bodies, blue channel), and were stained with an antibody against α-tubulin (brain, axons, and pharynx, red channel). (C) wnt2 was expressed pre-pharyngeally (prephx), concentrated around the lateral edges and ventrally posterior to the photoreceptors. (D) sFRP-1: anterior to the photoreceptors (ant) and includes a ventral medial stripe of expression that extends posteriorly from the anterior tip of the head. sFRP-1 was also expressed around the distal tip of the pharynx (phx). sFRP-2 was expressed pre-pharyngeally. sFRP-3 was expressed in the pharynx (phx) and throughout the body plan (arrows). Scale bars, 200µm.

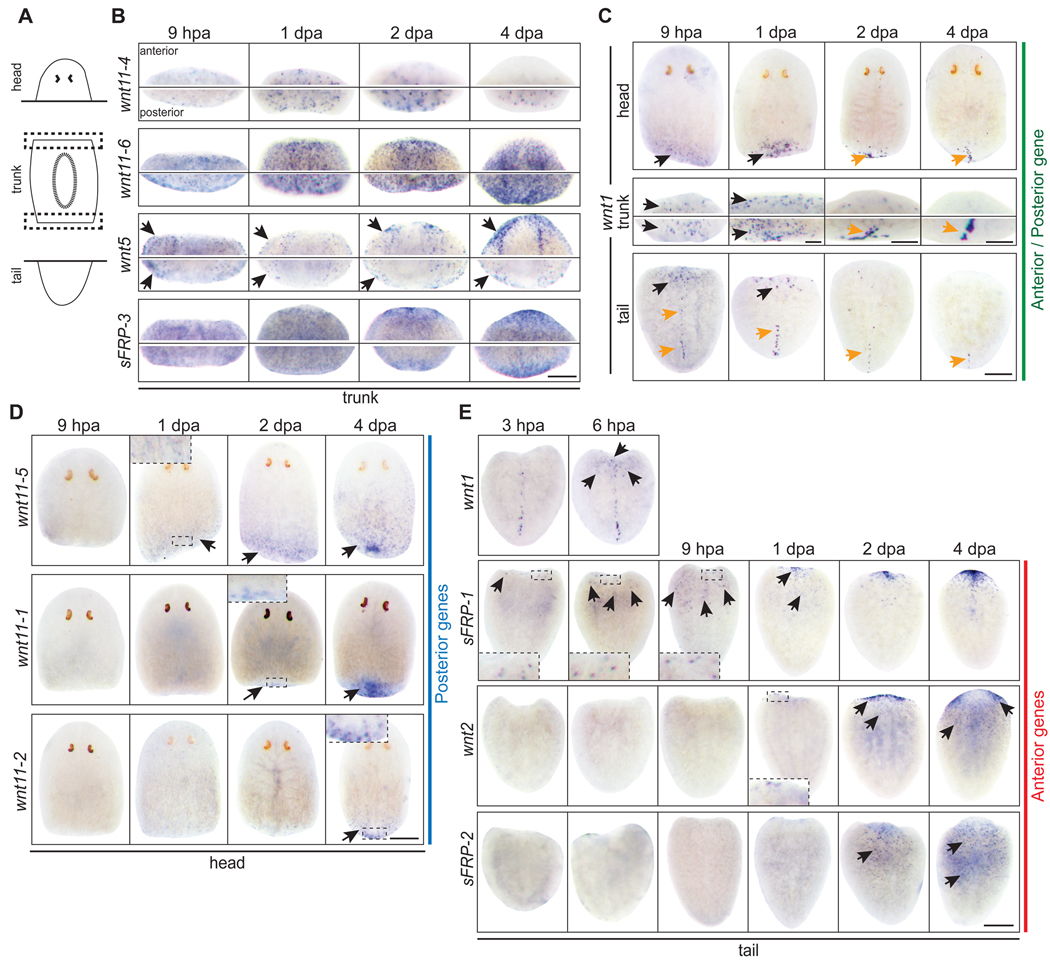

wnt and sFRP genes are expressed in succession after amputation

We next investigated whether the secreted components of the Wnt signaling pathway are expressed in distinct patterns during early stages of regeneration in head, trunk, and tail fragments. While wnt11-4, wnt11-6, wnt5, and sFRP-3 were broadly expressed in adult worms (Fig. 2), their expression during regeneration was minimally informative and we did not pursue them for further detailed analysis (Fig. 3B). Similar to a previous report (Petersen and Reddien, 2009), we found that although wnt1 expression was limited to 11.5 ± 0.7 (n=28 worms) posterior dorsal cells in intact animals (Fig. 2A), it was highly expressed along the entire wound at anterior and posterior amputation planes in heads, trunks, and tails between 6 and 9 hours post amputation (hpa) (Fig. 3C). wnt1 was also expressed along lateral facing amputations and at sites of wounding without amputation (Fig. S15). Therefore, wnt1 expression appears to represent an early response to wounding (Fig. S15) (Petersen and Reddien, 2009) that is activated regardless of the anterior or posterior orientation of the wound.

Fig. 3.

wnt and sFRP genes exhibit rapid and distinct responses to amputation. (A) Schematic of amputations and the resulting fragments. (B,C) Trunks shown are the anterior and posterior wound site (dotted boxes) from the same fragment. (B) Trunk fragments: wnt11-4, wnt11-6, wnt5, and sFRP-3 were expressed in patterns that resembled the intact expression patterns. (C) All 3 fragments: wnt1 was expressed in both anterior and posterior wounds by 6–9 hpa (black arrows). A stronger expression domain appeared by 2–4 dpa in posterior regions that resolved into a stripe resembling the wnt1 expression pattern in intact animals (orange arrows). In tail fragments, the pre-existing posterior dorsal stripe regressed with time (orange arrows). (D) Head fragments: wnt11-5, wnt11-1, and wnt11-2 were induced at distinct times at posterior wounds (black arrows). (E) Tail fragments: sFRP-1, wnt2, and sFRP-2 were induced at distinct times at anterior wounds (black arrows). wnt1 expression is shown at 3 and 6 hpa to compare with sFRP-1. (B–E) hpa; hours post amputation. dpa; days post amputation. Scale bars, 200µm.

In head fragments, which regenerate a tail after amputation, early wnt1 expression was followed by wnt11-5 expression at 1 dpa, wnt11-1 at 2 dpa, and wnt11-2 at 4 dpa (Fig. 3D). This demonstrates a sequence of posterior-specific gene expression during de novo tail formation following wnt1 up-regulation, which is consistent with the function of wnt1 to promote tail fate (Adell et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Rink et al., 2009). Paradoxically, β-catenin signaling must be suppressed at anterior wounds to regenerate a head (Gurley et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2008), but wnt1 is strongly expressed at both anterior and posterior amputations (Fig. 3C) (Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Rink et al., 2009). These data suggest that a mechanism must exist to guarantee that the burst of wnt1 expression at anterior wounds does not lead to levels of β-catenin activity sufficient to specify tail fate. One possible strategy would employ the anterior-specific expression of a wnt inhibitor during early stages of regeneration.

Indeed, we consistently observed three or four sFRP-1 positive cells by 3 hpa at the anterior wound in tail fragments, indicating that anterior fate may have been selected prior to the strong expression of wnt1 at 6–9 hpa (Fig. 3E). The expression of sFRP-1 expanded over the next 6 hours and a strong cluster of sFRP-1 expressing cells accumulated in the anterior of the tail by 1 dpa. Two additional anterior markers, wnt2 and sFRP-2, were not detected until 1–2 dpa (Fig. 3E).

The observation that sFRP-1 was expressed at anterior wounds just prior to wnt1 might explain the choice of anterior fate despite strong wnt expression. However, this scenario would require an additional signaling system to initiate sFRP-1 expression specifically at anterior wounds. Furthermore, the limited number of cells that express sFRP-1 at 3–9 hpa would suggest that a more complicated mechanism exists for the anterior-specific inhibition of β-catenin activity during regeneration. Indeed, the lack of anterior fate defects following sFRP-1(RNAi), tested by dsRNA injection and feeding (data not shown)(Gurley et al., 2008), along with the irradiation experiments described below suggest that the early sFRP-1 expression may not be functionally required for anterior fate choice. Nonetheless, the distinct spatial and temporal patterns of gene transcription in head and tail fragments will provide useful readouts for dissecting the function of genes that control distinct steps of the regeneration process.

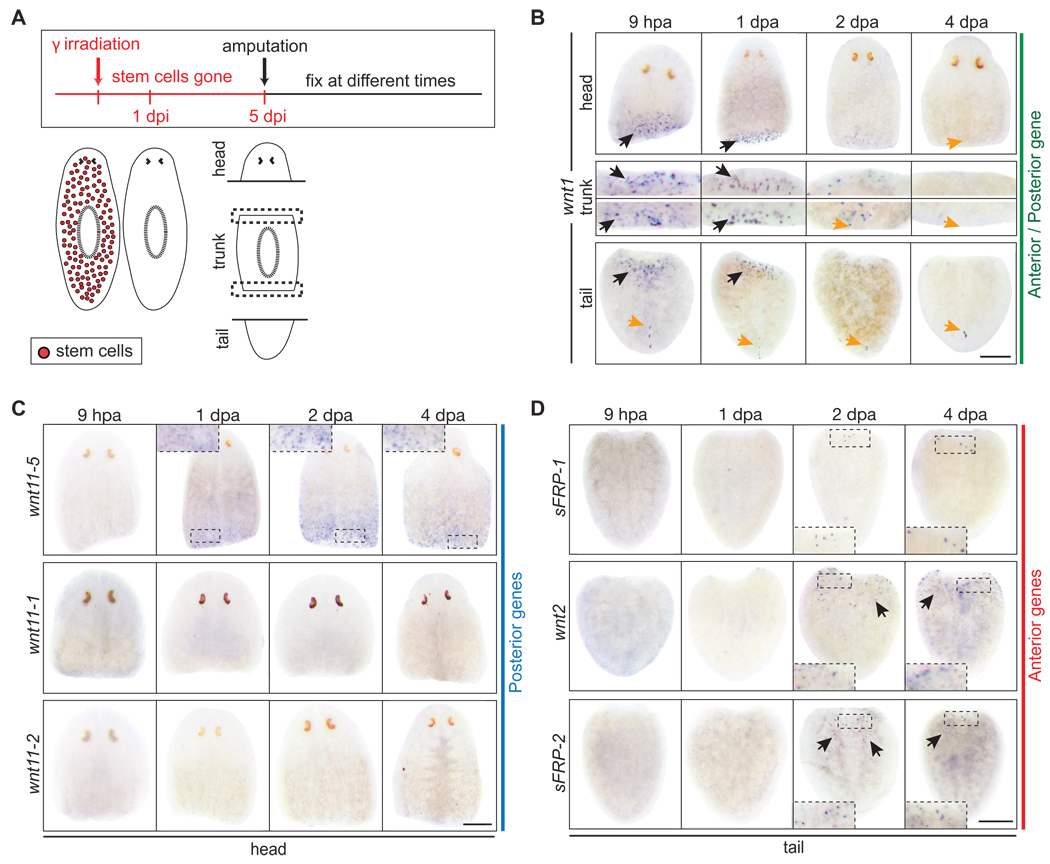

A/P fate choice is independent of stem cells

In planarians, irradiation is known to eliminate stem cells rapidly and efficiently (Bardeen and Baetjer, 1904; Dubois, 1949; Eisenhoffer et al., 2008). Five days after exposing animals to 100 Gy (10,000 rads), neither stem cells nor proliferation can be detected and the animals lack regenerative capacities (Fig. S16A). Thus, we tested the necessity of stem cells for the anterior versus posterior fate choice by amputating irradiated animals (Fig. 4A). In the absence of stem cells, wnt1 was strongly expressed at both anterior and posterior amputation planes in head, trunk, and tail fragments (Fig. 4B) (Petersen and Reddien, 2009). Over a 4-day period, the early burst of wnt1 expression faded with kinetics similar to control animals (Fig. 3C), but the posterior stripe never emerged in head or trunk fragments (Fig. 4B). In irradiated head fragments, wnt1 expression preceded the expression of wnt11-5 at posterior wounds (Fig. 4B,C) in a fashion indistinguishable from unirradiated controls (Fig. 3C,D), suggesting that both the wound response and initial choice of posterior fate are stem cell independent. Because new cells are not being generated 5 days post irradiation (dpi), the observed wnt11-5 expression also indicates that differentiated anterior cells in intact animals, which are suddenly located at the posterior end of a head fragment after amputation, can interpret their new posterior location and modify gene expression accordingly. In contrast, posterior-specific expression of wnt11-1 and wnt11-2 was absent in irradiated head fragments, indicating that stem cells are required for their expression (Fig. 4C). However, like almost all of the genes in this study, wnt11-1 and wnt11-2 are unlikely to be expressed by stem cells because the bulk of expression was unperturbed in intact irradiated animals (Fig. S16B,C). Therefore, wnt11-1 and wnt11-2 are more likely expressed by stem cell descendants in newly-regenerated tail tissue. Together, the data suggest that after a posterior amputation in otherwise unperturbed animals, wnt1 is expressed by differentiated cells as a wound response (Fig. 4B, S15), which is followed by wnt11-5 expression in pre-existing tissue near the wound as this region acquires posterior identity. wnt11-1 and wnt11-2 are subsequently expressed in a stem cell dependent fashion at later time points as the new tail forms.

Fig. 4.

Stem cells are not required for wound response or A/P axis specification (A) Diagram of experimental approach. Stem cells were eliminated in intact planarians within 1 day post irradiation (dpi). Animals were amputated 5 dpi and fixed at various times post amputation. (B) wnt1 was expressed in an early burst at anterior and posterior wounds in irradiated head, trunk, and tail fragments (black arrows). The posterior stripe of wnt1 expressing cells (orange arrows) that is present in intact animals did not form anew in head or trunk fragments, which must regenerate a new tail, but remained visible in tail fragments. (C) Irradiated head fragments expressed only one of the posterior genes, wnt11-5, by 1 dpa (compare to Fig. 2D). (D) Irradiated tail fragments expressed anterior wnts and sFRPs, albeit later and at reduced levels than controls (compare to Fig. 2E). Scale bars, 200µm.

Interestingly, we also noted that the posterior stripe of wnt1 expression in intact animals is sensitive to irradiation (Fig. S16B,D). The dorsal location of these wnt1 expressing cells and their delayed disappearance after irradiation suggests that they are not stem cells, but that they do undergo rapid turnover in intact animals, and thus are under constant and tight regulation. We interpret the lack of a wnt1 posterior stripe in irradiated head and trunk fragments to indicate that this stripe of cells is not formed by previously existing tissue during tail regeneration, but is formed anew from stem cell progeny. Because the burst of wnt1 expression after wounding is irradiation insensitive, it seems likely that the posterior stripe of wnt1 expressing cells in intact animals are unrelated to cells that express wnt1 after wounding. This implies that the two domains of wnt1 expression are under the control of separate regulatory elements.

In irradiated tail fragments, wnt1 was strongly expressed at the anterior amputation between 6 and 9 hours (Fig. 4B). Anterior expression of sFRP-1 was detected by 2 dpa, when wnt2 and sFRP-2 were also detected (Fig. 4D). Thus, in the complete absence of stem cells, and despite a strong induction of wnt1 at the anterior wound, differentiated cells located at the anterior end of a tail fragment recognize their new relative location and change their gene expression accordingly. Although the duration, overall expression level, and kinetics of anterior-specific markers (sFRP-1, wnt2, sFRP-2) were drastically reduced in irradiated tail fragments compared to controls, expression of all three genes was consistently detected at the anterior end.

We interpret the combined data from head and tail fragments to reveal that cells throughout the animal are capable of expressing anterior- or posterior-specific genes during regeneration that they would otherwise never express in the intact animal. Moreover, this anterior/posterior plasticity does not require the presence of stem cells.

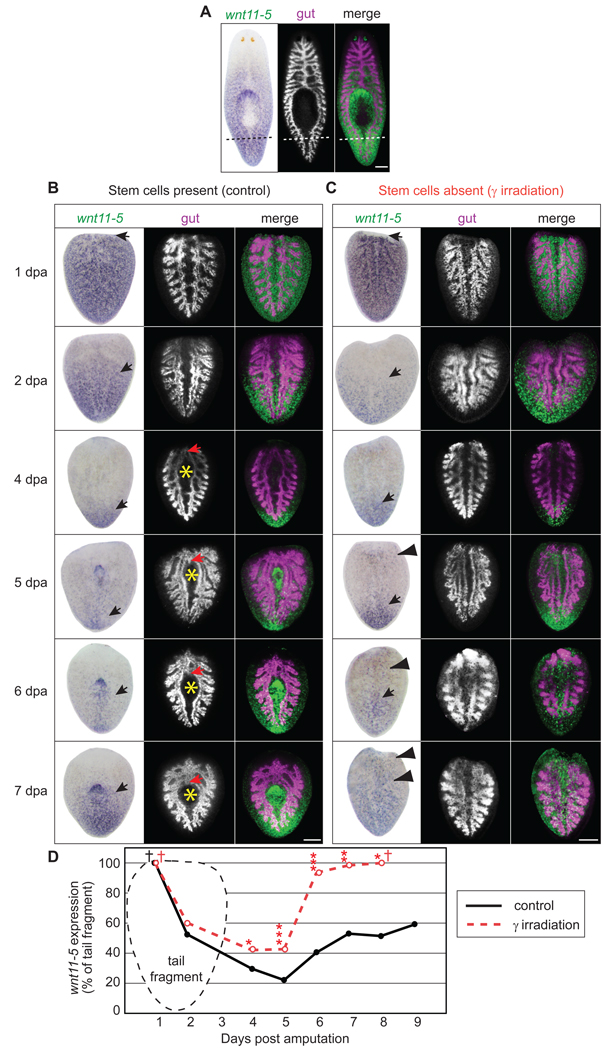

Response following A/P axis decision is stem cell independent

To investigate the global A/P response to amputation, we examined wnt11-5 expression dynamics. wnt11-5 was expressed in a strong posterior to anterior gradient in intact animals Fig. 2A, Fig. 5A, (Gurley et al., 2008; Pearson et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2008) spanning 73.2 ± 0.7% of total body length (n=39 worms). As a result, freshly amputated tail fragments strongly express wnt11-5 across 100% of the fragment’s length (Fig. 5B) and must eventually re-establish the proper posterior to anterior gradient. It has been previously shown that wnt11-5 expression retreats from the anterior end within 4–5 dpa, demonstrating that cells throughout a tail fragment can respond to their new relative A/P location after amputation (Fig. 5B,D) (Petersen and Reddien, 2008; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). Because wnt11-5 was the only positional marker used in previous analyses, we sought to better understand the timing of this dynamic process in the context of the expression kinetics of other secreted wnt pathway-related genes.

Fig. 5.

wnt11-5 expression dynamics and tissue remodeling in tail fragments. (A–C) Specimens were developed with NBT-BCIP for wnt11-5 (false-colored in green for merge) and Cy3-tyramide for porcn-1 (gut, magenta in merge). (A) wnt11-5 expression and gut anatomy in intact adults prior to amputation. Dashed line; plane of amputation for 4B,C. (B) Control tail fragments 1–7 dpa. Between 1 dpa and 5 dpa, the anterior extent of wnt11-5 expression (black arrow) regressed posteriorly. Gut remodeling was not obvious until branches began to fuse anteriorly (red arrow) and a new pharyngeal pouch (yellow asterisk) began to expand around 4 dpa. By 7 dpa, wnt11-5 expression expanded to the anterior region of the new pharynx. (C) Irradiated tail fragments 1–7 dpa. wnt11-5 regressed to the posterior tip of the tail from 1–5 dpa, similar to controls (arrow). After 5 dpa, ectopic wnt11-5 expression (arrowheads) was observed near the anterior amputation edge and wnt11-5 was expressed across the entire fragment by 7 dpa. No gut remodeling was observed in irradiated fragments. (D) Quantification of the extent of wnt11-5 expression in tail fragments during regeneration. Each data point is the median from ≥15 worms (See Fig. S17 for plot of all data). Single asterisks, p<0.05; double asterisks, p<0.01; triple asterisks, p<0.001; as determined by 1 way ANOVA comparing unirradiated to irradiated fragments. Cross bar; median value is not statistically different from 100% as determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test. Scale bars, 200µm.

At 1 dpa, when sFRP-1 expressing cells formed a distinct cluster at the anterior end of tail fragments (Fig. 3E), wnt11-5 was still expressed throughout the entire tail fragment from the posterior to anterior tip (Fig. 5B,D). Between 1 dpa and 4 dpa, when sFRP-2 and wnt2 expression was detected at the anterior end (Fig. 3E), wnt11-5 expression exhibited a rapid regression toward the posterior end (Fig. 5B,D). This dynamic shift in expression suggests that new anterior and posterior zones are established by 1 dpa and cells throughout the tissue then acquire new positional identity along the A/P axis. The lack of wnt11-5 regression prior to 1 dpa suggests that there is a 24 hour delay in positional reorganization after amputation. Additionally, we noted that wnt11-5 expression regressed to 24.3 ± 1.9% of body length by 4 dpa (Fig. 5B,D). Because intact animals express wnt11-5 along 73.2 ± 0.7% of body length (Figs. 2A and 5A), the regression of wnt11-5 at 4 dpa represents a large overshoot of the desired final A/P position and requires that additional reorganization along the A/P axis must subsequently occur (discussed below).

Remarkably, irradiated tail fragments, which did not contain stem cells or exhibit cell division (Fig. S16A), displayed a dynamic posterior shift in wnt11-5 expression similar to controls, including the overshoot at 4 dpa (Fig. 5C,D, S17). Combined with the expression of posterior- and anterior-specific genes in irradiated head and tail fragments, respectively, this indicates that the pre-existing cells distributed along the A/P axis can dynamically change their transcriptional output to match their new relative A/P location in a stem cell independent manner. Thus, while it is clear that new stem cell progeny acquire fate appropriate to their new position in regenerating worms, cells of the pre-existing tissues also change their positional identity.

The assessment of new A/P position appears to depend on β-catenin signaling. Globally increased β-catenin activity, induced via APC(RNAi), caused the regeneration of tails instead of heads at the anterior wounds of tail fragments (Gurley et al., 2008). The bulk of wnt11-5 expression retreated to the posterior end of tail fragments as in controls (Fig. S18) in both unirradiated and irradiated APC(RNAi) animals. Surprisingly, when irradiated βcatenin-1(RNAi) animals were amputated, wnt11-5 expression did not retreat to the posterior end of the tail and instead remained strong throughout the entire fragment for at least 4 days (Fig. S18). This is strikingly different from irradiated control(RNAi) tail fragments, which exhibited normal wnt11-5 regression (Fig. 5C, S18B). Thus, β-catenin is required for the proper regression of wnt11-5 to the posterior end of tail fragments.

Interestingly, our data show that during the first 24 hours after amputation, wnt1 and wnt11-5, which function through β-catenin at posterior wounds to initiate tail regeneration (Adell et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Rink et al., 2009), are strongly expressed at the anterior wound of untreated tail fragments. Yet, their expression at this location does not cause tail formation and a head regenerates instead. It remains unknown how β-catenin activity is reduced at anterior amputations to form anterior structures in an environment so rich in wnt expression. To date the only identified planarian homologs of known secreted Wnt inhibitory proteins are the sFRPs. Our expression data and RNAi analysis of the sFRPs suggest that they may not be required to modulate β-catenin activity at anterior amputations, but this observation may be due to incomplete gene silencing. We have been unable to detect other secreted inhibitors, such as Wnt Inhibitory Factors (WIFs), in the planarian genome.

Stem cells are required for anatomical remodeling and proper tissue integration

While specifying new positional information, a tail fragment must also reorganize the existing gastrovascular and nervous systems to accommodate the regenerating head and reestablish proper form and function. The gut of an intact animal is composed of a single main branch anteriorly, which bifurcates at the pharynx into two parallel posterior branches (Fig. 5A). Therefore, following amputation, a tail fragment contains two parallel gut branches running the length of the animal that will eventually make way for a new pharyngeal cavity and connect to form a new anterior branch. It is currently unknown how planarian tissue remodeling is accomplished and to what extent this process depends on stem cells.

Using probes for wnt11-5 and Smed-porcn-1 (Gurley et al., 2008), we performed double in situ hybridizations to simultaneously monitor changes in positional identity and gut anatomy, respectively. We observed that the rapid retreat of wnt11-5 expression from day 1 to day 4 was not accompanied by drastic changes in gut morphology (Fig. 5B), suggesting that global changes in positional identity occur prior to extensive anatomical remodeling. By day 4, the two gut branches appeared to fuse at the anterior end and also began to bow, reflecting the formation of a new pharyngeal cavity (Fig. 5B). Between days 4 and 7, the single anterior gut branch lengthened, the pharyngeal cavity and newly regenerated pharynx were shifted towards the posterior, and the posterior gut branches shortened (Fig. 5B). By day 7, the entire gastrovascular system in the tail fragments had been remodeled to approximate the shape and proportion of a small intact adult animal. Interestingly, the excess posterior regression of wnt11-5 at day 4 was corrected by 7 dpa, as wnt11-5 expression had expanded anteriorly to the pharynx, similar to the expression observed in intact adult animals (Fig. 5B). Perhaps the anterior boundary of wnt11-5 expression is coordinated with regenerating and/or remodeling tissues such as the pharynx or gut (Fig. 5B). By day 14, tail fragments had achieved apparently normal proportions (data not shown).

It is well established that the elimination of stem cells via irradiation renders planarians unable to regenerate (Bardeen and Baetjer, 1904; Dubois, 1949; Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Reddien et al., 2005), but it remains unknown to what extent existing tissues can remodel in the absence of stem cells. After amputation, irradiated planarians exhibit a normal burst of apoptosis, indicating that at least some aspects of tissue remodeling are independent of stem cells (Pellettieri et al., 2009). To test this in more detail, we amputated animals after eliminating their stem cells by exposure to irradiation, and simultaneously monitored changes in positional identity and gut anatomy as above. As expected, irradiated tail fragments displayed a regression of wnt11-5 expression through day 4 (Fig. 5B,C and data not shown). However, in the absence of stem cells (Fig. S16A), two discrete parallel gut branches were present over the entire time course (Fig. 5C). The anterior ends of the gut branches failed to fuse, a single anterior branch never formed, there was no indication of a new pharyngeal cavity, and the posterior branches did not shorten (Fig. 5C). Astonishingly, despite lacking the ability to generate new tissue, irradiated fragments displayed a re-expansion of wnt11-5 expression after 5 dpa (Fig. 5C,D). However, unlike unirradiated controls where wnt11-5 re-expansion halted at the level of the pharynx, wnt11-5 expression in irradiated animals continued to expand until it covered the entire length of the fragment (Fig. 5C,D). Thus, as wnt11-5 expression expands forward on day 5 in untreated animals, we suggest that signals from the regenerating and/or remodeling tissue located near the anterior end of the pharyngeal cavity halt wnt11-5 expansion and therefore re-establish the posterior-anterior wnt11-5 expression gradient. In the absence of stem cells, tissue regeneration and gut remodeling do not occur and wnt11-5 expression in pre-existing cells is no longer restricted from progressing anteriorly.

Altogether, our data demonstrate that although pre-existing cells can assess their new A/P position in the absence of stem cells, anatomical tissue remodeling in planarians depends on the presence of stem cells. Moreover, the integration of A/P position with the anatomy requires communication between pre-existing cells, regenerating tissue, and actively remodeling tissue.

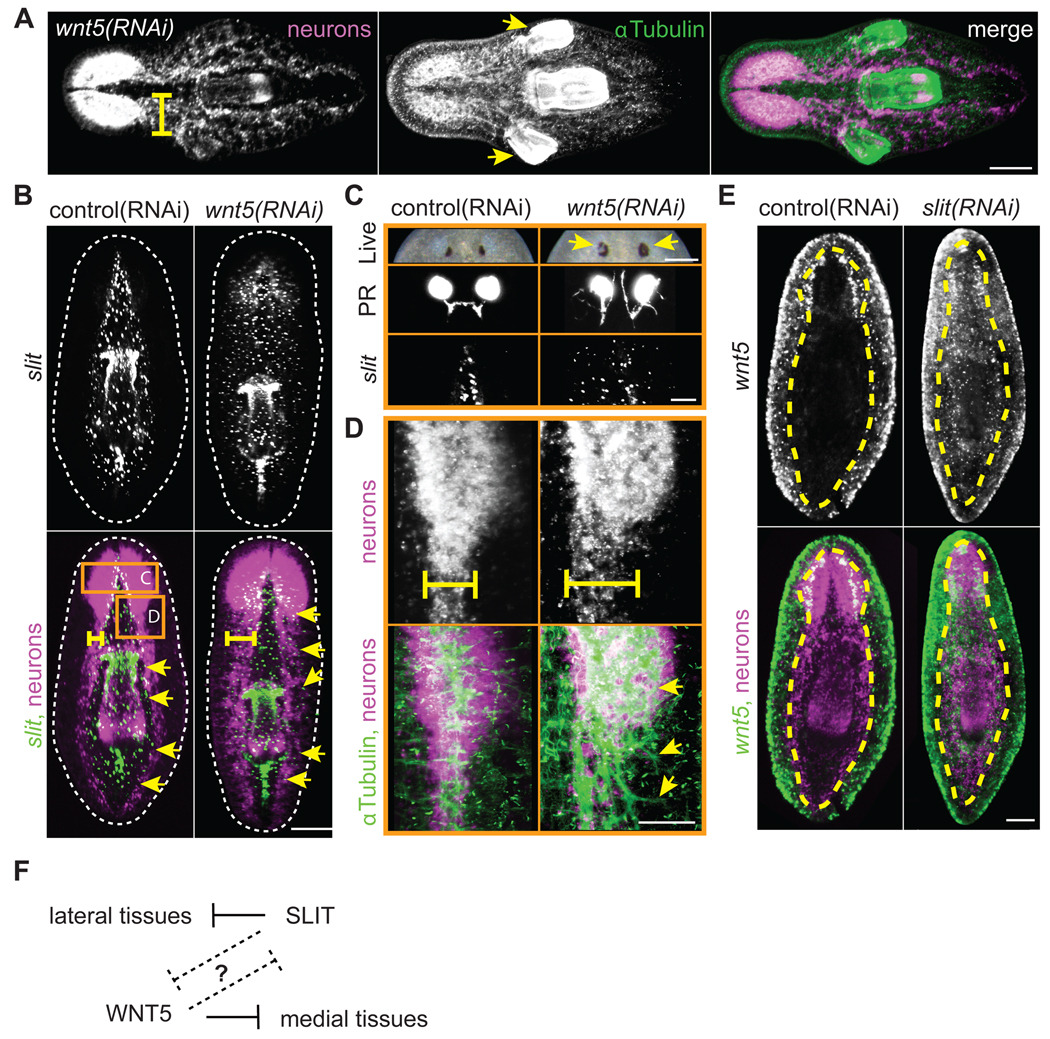

WNT5 and SLIT reciprocally regulate the mediolateral axis

The robust yet distinct expression of wnt genes in intact and regenerating planarians suggests that these genes may have diverse functions in tissue maintenance and/or regeneration. To investigate the function of planarian wnt genes, we silenced each Smed-wnt gene using RNAi and amputated worms transversely to generate head, trunk, and tail fragments.

Silencing Smed-wnt5 caused profound alterations in the planarian body plan. Consistent with the previously reported wnt5(RNAi) deflected-brain phenotype (Adell et al., 2009), we observed that in all cases (100%) wnt5(RNAi) animals exhibited a severe thickening of the brain and ventral nerve cords (VNCs; Fig. 6A,B,D). However, we additionally noted that approximately 10% of wnt5(RNAi) trunks developed one or two ectopic pharynges lateral to the original pharynx (Fig. 6A). Because wnt5 is mainly expressed lateral to the VNCs and along the body periphery (Fig. 2B) (Adell et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2008; Marsal et al., 2003), this phenotype is consistent with a role for WNT5 in inhibiting the lateral spread of more medially-located tissues. To further explore the extent of tissue expansion, we analyzed the expression of Smed-slit, a marker of the planarian midline (Cebrià et al., 2007). Ventrally, slit is expressed in a medial domain bounded laterally by the VNCs (Fig. 6B). In 100% of wnt5(RNAi) animals examined, ventral slit expression expanded beyond the boundary of the VNCs and out toward the body periphery (Fig. 6B,C). In the photoreceptors, ectopic pigment was deposited in lateral regions and axons projected laterally in all directions (Fig. 6C). In fact, axon tracts throughout the nervous system projected laterally (Fig. 6B, D). We suggest that WNT5 is secreted from ventral lateral cells to restrict the lateral expansion of the nervous system and midline tissues, including the pharynx and slit expressing cells (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

WNT5 and SLIT reciprocally pattern the mediolateral axis. (A–E) Neurons; PC2 riboprobe (magenta in merges) (A) wnt5(RNAi) trunk fragments exhibited laterally expanded cephalic ganglia, defasciculated axon tracts (yellow bar), and ectopic lateral pharynges (yellow arrows) by 15 dpa. Brain, axons, and pharynx; α-Tubulin antibody (green in merge). (B) Lateral expansion of the midline in trunk fragments 15 dpa. Midline; slit riboprobe (green in merge). Yellow bar; width of VNCs. Yellow arrows; lateral extent of slit expression. Dotted line; periphery of animal. Note that slit expression was bounded by the VNCs in control animals. (C–D) Higher magnification of regions boxed in panel B. Regenerating wnt5(RNAi) trunks at 15 dpa display (C) ectopic pigment (yellow arrows) around the photoreceptor (PR) pigment cup (live image is 22 dpa) and aberrant PR axon projections. PR axons; VC-1 antibody. Midline; slit riboprobe. (D) Axons; α-Tubulin antibody (green in merge). Note that wnt5(RNAi) axon tracts were defasciculated and disorganized (yellow arrows). (E) slit(RNAi) caused ectopic expression of wnt5 (green in merge) across the midline. Yellow dashed line; outer edge of the ventral nerve cords. (F) Model. WNT5 and SLIT act reciprocally, either directly or indirectly, to properly pattern the mediolateral axis. Scale bars; (A–B, E) 200µm, (C,D) 100µm.

Because wnt5 is required to restrict the expression of slit, we next assayed whether slit is reciprocally required to restrict the expression of wnt5. As expected, slit(RNAi) animals exhibited a collapsed nervous system along the midline (Fig. 6E) (Cebrià et al., 2007). Interestingly, ventral wnt5 expression expanded and was no longer restricted to lateral regions (Fig. 6E). These data demonstrate that wnt5 and slit are reciprocally required to organize the planarian mediolateral axis by restricting the expansion of medial and lateral tissues, respectively.

However, two additional observations suggest that control of the mediolateral axis is much more complex than we currently appreciate. First, a second marker of lateral tissue identity (H1.3b) that is expressed in cells near the periphery (Pearson et al., 2009) is unaffected in both wnt5(RNAi) and slit(RNAi) animals (Fig. S19). This illustrates that the entire mediolateral axis is not necessarily disrupted by wnt5(RNAi) or slit(RNAi) and that there are likely to be additional unidentified territories along this axis. Second, although the ventral domain of medial slit expressing cells expanded laterally in wnt5(RNAi) animals, the dorsal midline stripe of slit expressing cells and the dorsal posterior midline stripe of wnt1 expressing cells were both unaffected (Fig. S19). Thus, the mediolateral axis may be differentially controlled along the dorsoventral axis. In summary, our data demonstrate that a balance is struck between WNT5 and SLIT signaling to help organize the planarian mediolateral axis (Fig. 6F).

Wnt5 signaling also has midline functions during zebrafish development where it is required for the midline convergence of bilateral precursors for unpaired organs including the pancreas, liver, and heart. In this context, the Wnt ligands are expressed in midline structures and thus provide an attractive cue for cell migration. In planarians, WNT5 may instead be inhibitory, expressed in the lateral region to restrict the lateral expansion of medial cells and tissues. Alternatively, planarian WNT5 may function to promote lateral cell fate. In Drosophila, Wnt5 mediates embryonic axon defasciculation and/or dendritic refinement (Fradkin et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2010). However, loss of Drosophila Wnt5 function leads to failed defasciculation while loss of planarian wnt5 leads to the lateral extension of axons, which may indicate excess defasciculation (Fig. 6D).

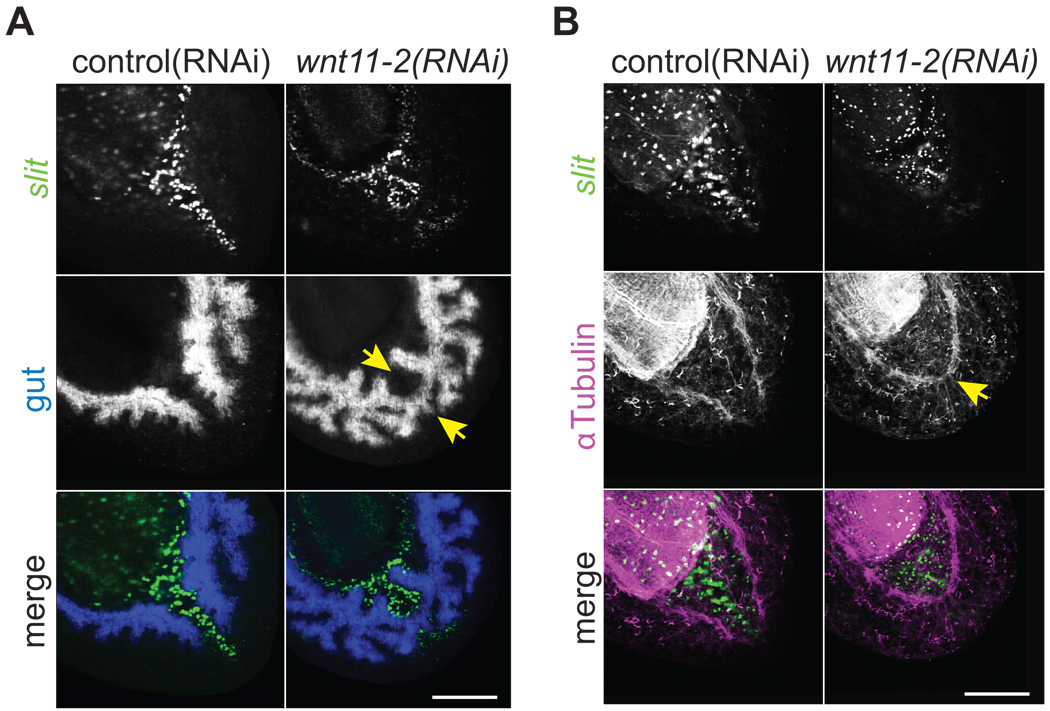

Smed-wnt11-2 patterns posterior tissues

Smed-wnt11-2 was superficially expressed in the tail in dorsal and ventral domains and in a small stripe of cells along the posterior midline (Fig. 2A). Double in situ hybridization to detect wnt11-2 and slit transcripts revealed that the midline wnt11-2 expressing cells are located just posterior to slit expressing cells, and are embedded between the dorsal and ventral domains (Fig. 2A). It was recently reported that silencing wnt11-2 results in a “rounded appearance” at posterior amputations and this was interpreted as a lack of tail regeneration (Adell et al., 2009). We instead find that the appearance of rounding is due to inappropriate midline patterning. We observed in wnt11-2(RNAi) animals that the left and right branches of the posterior gastrovascular system (gut) converged and fused at the midline (Fig. 7A) as did the posterior ventral nerve cords (Fig. 7B). These midline phenotypes were strikingly similar to those observed in slit(RNAi) animals (Cebrià et al., 2007), which suggested they may be a secondary consequence of SLIT signaling defects. Although slit positive cells were detected in approximately correct numbers in wnt11-2(RNAi) animals, they formed clusters that failed to elongate along the posterior midline (Fig. 7). wnt1 expression in the posterior dorsal midline was also perturbed in wnt11-2(RNAi) animals (Fig. S20). These data suggest that unlike Smed-hh(RNAi) or Smed-gli-1(RNAi) animals that do not regenerate tails, wnt11-2(RNAi) animals do regenerate tails, but the posterior midline fails to properly extend to the posterior pole. While it remains possible that our observations are the result of incomplete gene silencing, we suggest that rather than serving as a necessary factor for tail regeneration, WNT11-2 functions to recruit midline cells toward the posterior tip of the animal, maintaining a posterior barrier that separates the left and right sides of the gastrovascular and nervous systems.

Fig. 7.

wnt11-2 is required for posterior midline patterning. Single confocal sections from the tail region of trunk fragments 8 dpa. Images in panels A and B are different planes of section from same specimen. Note that the gastrovascular and nervous systems abnormally crossed the midline in wnt11-2(RNAi) animals. Midline; slit riboprobe (green in merges). (A) gut; porcn-1 riboprobe (blue in merge)(Gurley et al., 2008). (B) Ventral nerve cords; α-Tubulin antibody (magenta in merge). Scale bars; 200µm.

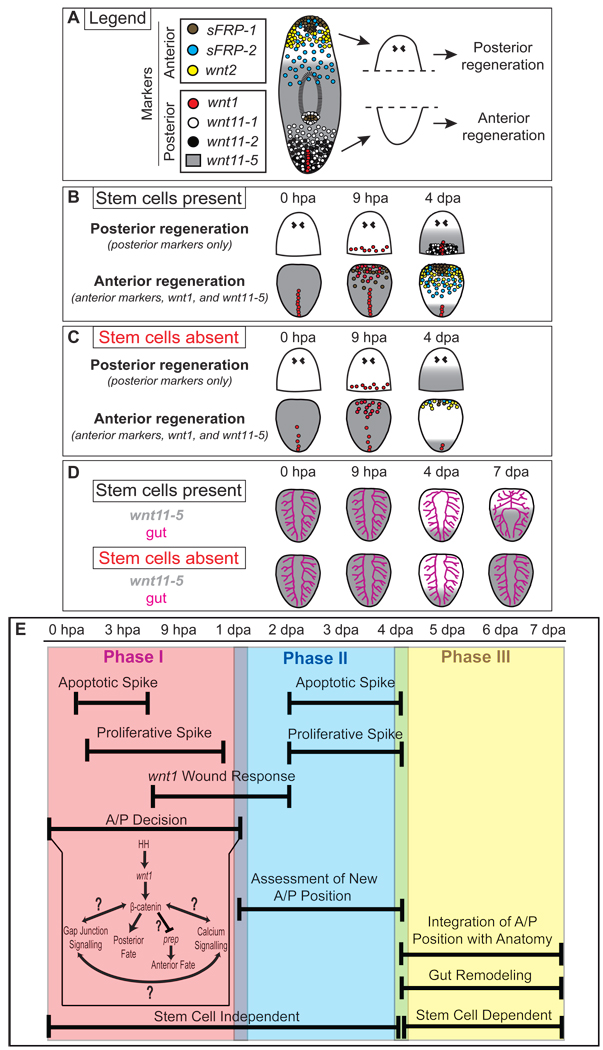

Conclusions

Wnt signaling plays essential roles in a diverse array of developmental processes including growth, patterning, fate choice, and differentiation. In planarians, Wnt signaling through β-catenin is critical for determining whether anterior or posterior structures will be regenerated. By monitoring the expression of multiple wnt and sFRP genes, which encode secreted activators and inhibitors of β-catenin, we uncovered fundamental aspects of planarian biology that provide insights into the striking regenerative plasticity of these animals.

Intact adult planarians express wnt and sFRP genes in discrete, complex, overlapping domains along the A/P axis in a manner that suggests a possible steady-state posterior to anterior gradient of β-catenin activity. This is reminiscent of the overlapping wnt expression patterns observed in the radially symmetric cnidarian body plan, the main axis of which is determined by β-catenin signaling (Augustin et al., 2006; Broun et al., 2005; Chera et al., 2009; Guder et al., 2006; Hobmayer et al., 2000; Holstein, 2008; Lengfeld et al., 2009; Momose et al., 2008; Momose and Houliston, 2007). The planarian expression patterns described here imply that Wnt signaling not only controls the patterning of the main body axis, but also plays roles that are restricted to specific tissues in multiple locations along the A/P axis. Moreover, the distinct wnt and sFRP expression patterns (Fig. 2), and the RNAi phenotypes resulting from wnt5(RNAi) (Fig. 6) (Adell et al., 2009) and wnt11-6(RNAi) (Adell et al., 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2007) may indicate that perhaps there exist as yet undefined tissue boundaries throughout the entire planarian body plan. For example, the anterior extent of wnt11-5 expression correlates with the posterior extent of sFRP-2 expression (Fig. 2). The expression of these genes may be controlled in a complex interdependent manner. To produce viable adult animals of appropriate proportion, these cellular boundaries must re-establish after an amputation in which the size and shape of the animal has been drastically altered.

During normal regeneration, the patterns of wnt and sFRP expression reveal that the process of redefining positional identity in a regenerating planarian is highly dynamic and complex. Within 24 hpa, planarians undergo a distinct series of responses while concurrently assigning new boundaries along the A/P axis (Fig. 8). During this process, the intricate pattern of wnt and sFRP expression that was present prior to amputation is not immediately reset. Instead, many of these genes are first expressed in broad patterns that dramatically refine over the course of regeneration (Fig. 3). Additionally, anterior and posterior wounds exhibit a distinct progression of wnt and sFRP expression in which some genes are not activated until 2 or 4 dpa. This delay likely reflects expression in distinct cell types that have yet to be born as the new head and tail are being generated. Finally, our studies of irradiated animals demonstrate that many regenerative responses can be mounted by pre-existing tissues in the complete absence of cell division and without input from stem cells or newly-regenerated tissues. This is reminiscent of cnidarian regeneration. Here, wound healing is followed by organizer formation, which has been shown to occur without any cell division; the input of cell proliferation is only required to complete and maintain morphogenesis in the final phase of regeneration (Holstein et al., 2003).

Fig. 8.

Cartoon summary of expression and anatomical data, and a model for phases of A/P axis re-organization. (A) Expression patterns of anterior and posterior wnt and sFRP genes in intact planarians. Dashed line; plane of amputation used to generate head and tail fragments. (B) Sequence of gene expression during posterior and anterior regeneration in head and tail fragments, respectively. (C) Sequence of gene expression during regeneration in the absence of stem cells. wnt1 is expressed at the wound site as normal. Despite a decrease in expression levels compared to controls, posterior and anterior markers are expressed anew and A/P axis re-organization begins. wnt11-5 expression dynamics are very similar in irradiated and unirradiated animals. (D) Gut remodeling appears to lag behind the molecular re-organization of the A/P axis and does not occur in the absence of stem cells. After 4 dpa, wnt11-5 expression expands towards the anterior in control and irradiated animals, but in the absence of stem cells wnt11-5 expansion does not halt and is instead expressed along the entire A/P axis. (E) A model that divides planarian A/P axis re-organization into 3 phases and integrates what is known about planarian regeneration. Apoptotic and proliferative spikes are observed within 12 hpa. Around 6–9 hpa, the wnt1 wound-specific expression response is observed. Finally, the A/P decision is made sometime within 1 dpa, which has been shown to involved the Hh-wnt/β-catenin pathways, gap junction signaling, calcium signaling, and Smed-prep. Aside from proliferation, Phase I does not depend upon regeneration or the presence of stem cells. Phase II involves a fading of the wnt1 wound response by 2 dpa, followed by another round of spikes in apoptosis and proliferation. Concurrently, cells of the fragment assess their new A/P position. Aside from the proliferative response, Phase II also does not depend upon stem cells or regeneration. Finally, Phase III involves an integration of new A/P address with the remodeling anatomy, including the gut. This Phase is dependent upon stem cells.

Unlike previous studies that examined the expression of one or two genes, our current studies employed multiple markers of both anterior and posterior fate to monitor the A/P address of cells throughout tissue fragments during regeneration. Combining these data with previous investigations, we propose a three-phase model by which positional information is re-established along the A/P axis after amputation (Fig. 8E). Phase I lasts roughly 24 hours, during which time A/P fate is determined at the wound site (Gurley et al., 2008; Oviedo et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Yazawa et al., 2009). Phase I also consists of systemic responses that include increased mitotic activity (Baguñà, 1976; Saló and Baguñà, 1984), as well as local responses that include wnt1 expression (Fig. 4B)(Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Rink et al., 2009; Yazawa et al., 2009) and apoptotic cell death (Pellettieri et al., 2009). It is intriguing that wnt expression and apoptotic cell death are also features of vertebrate regeneration (Sirbulescu and Zupanc, 2009; Tseng et al., 2007). Which cell types express wnt and how this expression is activated after amputation in vertebrates remains unknown. Although Wnt signaling likely acts as a proliferation cue during regeneration in vertebrate progenitor cells (Stoick-Cooper et al., 2007b), the anteriorization defects elicited by βcatenin-1(RNAi) in planarians suggest that perhaps Wnt signaling plays an early role in cell fate choice during vertebrate regeneration as well.

During Phase II, which lasts until roughly day 5, cells throughout the fragment assess their new position and acquire a new A/P address. It is evident from the broad expression of wnt and sFRP genes along the A/P axis that the fragment now behaves as an entirely independent worm instead of an amputated fragment. With the exception of cell proliferation, both Phase I and Phase II proceed even in the complete absence of stem cells (This paper) (Pellettieri et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2009). During Phase III, positional identity along the A/P axis is coordinated with the regenerating and remodeling anatomy. Because regeneration and remodeling require stem cells, the third phase of A/P reorganization also requires stem cells and cell division.

Finally, functional analysis of planarian wnt and sFRP genes via RNAi silencing revealed that WNT5 plays a role in organizing the mediolateral axis. Our data suggest that WNT5 and SLIT function reciprocally to inhibit the spread of medial or lateral tissues, respectively, which include pigmented cells of the eye cup, photoreceptor axons, brain and ventral nerve cord cell bodies and axon tracts, the pharynx, slit expressing midline cells, and wnt5 expressing lateral cells. The mechanisms by which WNT5 and SLIT reciprocally regulate the mediolateral axis and coordinately organize it with the A/P and D/V axes remain to be determined.

Recent studies have implicated four other planarian pathways in the choice of head or tail. First, the simultaneous silencing of 3 ninepins, which typically function as structural components of invertebrate gap junctions, causes ectopic head formation much like the silencing of β-catenin (Oviedo et al., 2009). The treatment of planarians with drugs that likely antagonize planarian gap junctions also causes bipolar head regeneration, implying that some sort of cellular communication through gap junctions may be required for cells to adopt a posterior fate. Second, the treatment of planarians with drugs or dsRNA that result in either increased or decreased Ca2+ flux causes the regeneration of a head in the place of a tail (Nogi et al., 2009). These data suggest that perhaps a macroscopic gradient of Ca2+ or even a gradient of Ca2+ flux is required for tail formation. Third, Hh signaling was recently shown to activate β-catenin signaling by controlling wnt1 expression and altered Hh signaling can cause the regeneration of bipolar heads or tails (Rink et al., 2009; Yazawa et al., 2009). Interestingly, no clear anterior or posterior bias in Hh signaling has been detected early during regeneration. Fourth, Smed-prep is a TALE class homeodomain-containing transcription factor that is essential for anterior regeneration (Felix and Aboobaker, 2010). The phenotypes resulting from prep(RNAi) resemble those caused by partial silencing of either ptc or APC (Rink et al., 2009) and are likely hypomorphic. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that prep promotes anterior fate and may be post-transcriptionally repressed by β-catenin signaling to allow tail regeneration (Felix and Aboobaker, 2010). How all four of these pathways are integrated, including their upstream and/or downstream relationships, has yet to be determined and will be an exciting avenue of future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Agata for VC-1 antibody; Otto Guedelhoefer, Carrie Adler, and Bret Pearson for helpful comments on this manuscript; and Heidi Schoeneck for technical graphics support. Work supported by NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants RO-1 GM57260 and 5R37GM057260-12 to A.S.A. and F32GM082016 to K.A.G. T.W.H. is supported by the DFG (FOR 1036 and SFB 873). A.S.A. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version…

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adell T, Saló E, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. Smed-Evi/Wntless is required for beta-catenin-dependent and -independent processes during planarian regeneration. Development. 2009;136:905–910. doi: 10.1242/dev.033761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agata K, Soejima Y, Kato K, Kobayashi C, Umesono Y, Watanabe K. Structure of the planarian central nervous system (CNS) revealed by neuronal cell markers. Zoolog Sci. 1998;15:433–440. doi: 10.2108/zsj.15.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin R, Franke A, Khalturin K, Kiko R, Siebert S, Hemmrich G, Bosch TC. Dickkopf related genes are components of the positional value gradient in Hydra. Dev Biol. 2006;296:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguñà J. Mitosis in the intact and regenerating planarian Dugesia mediterranea n.sp.: II. Mitotic studies during regeneration, and a possible mechanism of blastema formation. J. Exp. Zool. 1976;195:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen CR, Baetjer FH. The inhibitive action of the Roentgen rays on regeneration in planarians. J. Exp. Zool. 1904;1:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Brockes JP, Kumar A. Comparative aspects of animal regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:525–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broun M, Gee L, Reinhardt B, Bode HR. Formation of the head organizer in hydra involves the canonical Wnt pathway. Development. 2005;132:2907–2916. doi: 10.1242/dev.01848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebrià F, Guo T, Jopek J, Newmark PA. Regeneration and maintenance of the planarian midline is regulated by a slit orthologue. Dev Biol. 2007;307:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebrià F, Newmark PA. Planarian homologs of netrin and netrin receptor are required for proper regeneration of the central nervous system and the maintenance of nervous system architecture. Development. 2005;132:3691–3703. doi: 10.1242/dev.01941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chera S, Ghila L, Dobretz K, Wenger Y, Bauer C, Buzgariu W, Martinou JC, Galliot B. Apoptotic cells provide an unexpected source of Wnt3 signaling to drive hydra head regeneration. Dev Cell. 2009;17:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois F. Contribution a´ l ‘e` tude de la migration des cellules de regeneration chez les Planaires dulcicoles. C.R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1949;229:747–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sánchez Alvarado A. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix DA, Aboobaker AA. The TALE class homeobox gene Smed-prep defines the anterior compartment for head regeneration. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradkin LG, van Schie M, Wouda RR, de Jong A, Kamphorst JT, Radjkoemar-Bansraj M, Noordermeer JN. The Drosophila Wnt5 protein mediates selective axon fasciculation in the embryonic central nervous system. Dev Biol. 2004;272:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliot B, Ghila L. Cell plasticity in homeostasis and regeneration. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/mrd.21206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guder C, Pinho S, Nacak TG, Schmidt HA, Hobmayer B, Niehrs C, Holstein TW. An ancient Wnt-Dickkopf antagonism in Hydra. Development. 2006;133:901–911. doi: 10.1242/dev.02265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley KA, Rink JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. Beta-catenin defines head versus tail identity during planarian regeneration and homeostasis. Science. 2008;319:323–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley KA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Stem cells in animal models of regeneration. StemBook, ed. The Stem Cell Research Community. StemBook; 2008. doi/10.3824/stembook.1.32.1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobmayer B, Rentzsch F, Kuhn K, Happel CM, von Laue CC, Snyder P, Rothbacher U, Holstein TW. WNT signalling molecules act in axis formation in the diploblastic metazoan Hydra. Nature. 2000;407:186–189. doi: 10.1038/35025063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein TW. Wnt signaling in cnidarians. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;469:47–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein TW, Hobmayer E, Technau U. Cnidarians: an evolutionarily conserved model system for regeneration? Dev Dyn. 2003;226:257–267. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science. 2001;294:2310–2314. doi: 10.1126/science.1065889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L, Finn RD, Gough J, Haft D, Hulo N, Kahn D, Kelly E, Laugraud A, Letunic I, Lonsdale D, Lopez R, Madera M, Maslen J, McAnulla C, McDowall J, Mistry J, Mitchell A, Mulder N, Natale D, Orengo C, Quinn AF, Selengut JD, Sigrist CJ, Thimma M, Thomas PD, Valentin F, Wilson D, Wu CH, Yeats C. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias M, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Saló E, Adell T. Silencing of Smed-betacatenin1 generates radial-like hypercephalized planarians. Development. 2008;135:1215–1221. doi: 10.1242/dev.020289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi C, Saito Y, Ogawa K, Agata K. Wnt signaling is required for antero-posterior patterning of the planarian brain. Dev Biol. 2007;306:714–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusserow A, Pang K, Sturm C, Hrouda M, Lentfer J, Schmidt HA, Technau U, von Haeseler A, Hobmayer B, Martindale MQ, Holstein TW. Unexpected complexity of the Wnt gene family in a sea anemone. Nature. 2005;433:156–160. doi: 10.1038/nature03158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengfeld T, Watanabe H, Simakov O, Lindgens D, Gee L, Law L, Schmidt HA, Ozbek S, Bode H, Holstein TW. Multiple Wnts are involved in Hydra organizer formation and regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009;330:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsal M, Pineda D, Salo E. Gtwnt-5 a member of the wnt family expressed in a subpopulation of the nervous system of the planarian Girardia tigrina. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mii Y, Taira M. Secreted Frizzled-related proteins enhance the diffusion of Wnt ligands and expand their signalling range. Development. 2009 doi: 10.1242/dev.032524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh BQ, Vinh le S, von Haeseler A, Schmidt HA. pIQPNNI: parallel reconstruction of large maximum likelihood phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3794–3796. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momose T, Derelle R, Houliston E. A maternally localised Wnt ligand required for axial patterning in the cnidarian Clytia hemisphaerica. Development. 2008;135:2105–2113. doi: 10.1242/dev.021543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momose T, Houliston E. Two Oppositely Localised Frizzled RNAs as Axis Determinants in a Cnidarian Embryo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e70. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV, Kaykas A. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: diseases and therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nrg1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Experimental studies of the regeneration of Planaria Maculata. Arch. Entw. Mech. Org. 1898;7:364–397. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Regeneration in planarians. Archiv. Entwick. Mech. Org. 1900;10:58–119. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Polarity and axial heteromorphosis. Am. Nat. 1904;38:502–505. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ, Nusse R. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303:1483–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1094291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev Biol. 2000;220:142–153. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogi T, Zhang D, Chan JD, Marchant JS. A novel biological activity of praziquantel requiring voltage-operated ca channel Beta subunits: subversion of flatworm regenerative polarity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Ishihara S, Saito Y, Mineta K, Nakazawa M, Ikeo K, Gojobori T, Watanabe K, Agata K. Induction of a noggin-like gene by ectopic DV interaction during planarian regeneration. Dev Biol. 2002;250:59–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo NJ, Morokuma J, Walentek P, Kema IP, Gu MB, Ahn JM, Hwang JS, Gojobori T, Levin M. Long-range Neural and Gap Junction Protein-mediated Cues Control Polarity During Planarian Regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BJ, Eisenhoffer GT, Gurley KA, Rink JC, Miller DE, Sánchez Alvarado A. Formaldehyde-based whole-mount in situ hybridization method for planarians. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:443–450. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Fitzgerald P, Watanabe S, Mancuso J, Green DR, Alvarado AS. Cell Death and Tissue Remodeling in Planarian Regeneration. Dev Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellettieri J, Sánchez Alvarado A. Cell turnover and adult tissue homeostasis: from humans to planarians. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:83–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Smed-betacatenin-1 is required for anteroposterior blastema polarity in planarian regeneration. Science. 2008;319:327–330. doi: 10.1126/science.1149943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CP, Reddien PW. A wound-induced Wnt expression program controls planarian regeneration polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17061–17066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906823106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires-daSilva A, Sommer RJ. The evolution of signalling pathways in animal development. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:39–49. doi: 10.1038/nrg977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph H. Observations and experiments on regeneration in planarians. Arch. Entw. Mech. Org. 1897;5:352–372. [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Sánchez Alvarado A. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Sánchez Alvarado A. Fundamentals of planarian regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:725–757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink JC, Gurley KA, Elliott SA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Planarian Hh signaling regulates regeneration polarity and links Hh pathway evolution to cilia. Science. 2009;326:1406–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.1178712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Ross E, Sánchez Alvarado A. SmedGD: the Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D599–D606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Sánchez Alvarado A. Identification of immunological reagents for use in the study of freshwater planarians by means of whole-mount immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. Genesis. 2002;32:293–298. doi: 10.1002/gene.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saló E, Baguñà J. Regeneration and pattern formation in planarians. I. The pattern of mitosis in anterior and posterior regeneration in Dugesia (G) tigrina, and a new proposal for blastema formation. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;83:63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Alvarado A, Newmark PA, Robb SM, Juste R. The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development. 2002;129:5659–5665. doi: 10.1242/dev.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HA. PhD Thesis. Germany: Universität Düsseldorf; 2003. Phylogenetic Trees from Large Datasets. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A. Maximum-likelihood analysis using TREE-PUZZLE. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0606s17. Chapter 6, Unit 6 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AP, VijayRaghavan K, Rodrigues V. Dendritic refinement of an identified neuron in the Drosophila CNS is regulated by neuronal activity and Wnt signaling. Development. 2010;137:1351–1360. doi: 10.1242/dev.044131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirbulescu RF, Zupanc GK. Dynamics of caspase-3-mediated apoptosis during spinal cord regeneration in the teleost fish, Apteronotus leptorhynchus. Brain Res. 2009;1304:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoick-Cooper CL, Moon RT, Weidinger G. Advances in signaling in vertebrate regeneration as a prelude to regenerative medicine. Genes Dev. 2007a;21:1292–1315. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Riehle KJ, Hubbert C, Major MB, Fausto N, Moon RT. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007b;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer K, Goldman N, Von Haeseler A. Bayesian Probabilities and Quartet Puzzling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997;14:210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Strimmer K, Von Haeseler A. Quartet Puzzling: A Quartet Maximum - Likelihood Method for Reconstructing Tree Topologies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:964–969. [Google Scholar]