Abstract

Ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury-induced oxidative stress plays an important role in the functional impairment of the bladder following acute bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) via induction of apoptosis. The purpose of this study was to investigate the time course of the bladder apoptosis, and apoptosis related molecular changes in the early stage of acute BOO. Twelve-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats were divided into control, acute BOO only (I), and acute BOO plus subsequent emptying (I/R) for 30, 60, 120 min, 3 days and 2 weeks. We examined the extent of bladder apoptosis, expression of Mn-superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), Bcl-2, Bax, caspase 3 and poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) in the bladder. Bladder apoptosis was significantly increased in the I/R group at 30, 60, and 120 min following bladder emptying. BOO plus subsequent emptying for 30, 60, 120 min showed significant decrease in MnSOD and Bcl-2 expression, and significant increase in caspase 3, Bax expression, and amounts of PAR. These results indicate that bladder apoptosis, induced by acute BOO and subsequent emptying, is associated with decreased MnSOD expression, increased PARP activity and imbalance in apoptosis pathways.

Keywords: Urinary Bladder Neck Obstruction, Apoptosis, Oxidative Stress, Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerases

INTRODUCTION

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is a common clinical problem and can occurs in several urologic diseases, including benign prostatic hyperplasia, urethral stricture disease, and congenital anomalies of the posterior urethral valve. BOO induces prolonged bladder overdistension, which produces damage of the detrusor muscle, progressive denervation of the bladder, detrusor receptor upregulation, and decrease in bladder wall blood flow, leading to bladder dysfunction and structural alterations (1). Currently, investigation of the primary cause of BOO and long-term partial BOO-induced changes of the bladder are well established (2, 3). However, acute complete outlet obstruction-induced early changes in the bladder have not been well studied. Several recent reports have indicated that acute urinary retention (AUR) induced not only bladder damage, but also functional and structural impairment of the heart, liver and kidney (4-6). Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the molecular changes and the underlying mechanisms in acute BOO.

Increasing evidence has suggested that ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury plays an important role in the progression of bladder dysfunction induced by BOO. Bladder overdistension causes increase in intravesical pressure and subsequent blood vessel compression, which induces relative decrease in blood flow to the bladder tissue, and results in ischaemia and hypoxia. Blood supply recovers after bladder emptying and allows reperfusion (7). A previous study has indicated that reperfusion following ischemia resulted in more severe bladder injury than ischemia itself (8). Reperfusion and re-oxygenation of ischemic bladder tissue increase generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which cause oxidative damage and cell apoptosis (9-11). However, apoptosis related molecular changes in the early stage of acute BOO have not been investigated.

In the present study, we investigated the time dependent changes in apoptosis related proteins in rat bladder following acute BOO. In addition, we also examined the activity of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), because recent studies have demonstrated that increase in ROS following I/R injury increases PARP activity and causes damage in several organs, such as brain, kidney and the heart (12-14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation

Twelve-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into three groups: control group (n=5), ischemia only group (I, n=5) and ischemia/reperfusion group (I/R, n=25). Acute BOO followed by bladder distension (ischemia) and drainage (reperfusion) was induced as described elsewhere (15) with slight modifications. Briefly, the rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg zoletil (tiletamine/zolazepam combination), and a 3-0 a silk ligature was placed around the prepuce of the rat penis. To promote bladder overdistension, 12 mL/kg Ringer solution was given intraperitoneally with intramuscular administration of furosemide (12 mg/kg) in I and I/R groups. A capacity of 3±0.5 mL was reached 15 min after this application. After the bladder was kept overdistended for 60 min, it was exposed via a lower midline abdominal incision and drained by a syringe with 18 G needle, until the rat woke up from anesthesia. Five rats in the I/R group was allowed to reperfuse for 30 min, 60 min, 120 min, 3 days and 2 weeks, respectively (n=5 in each I/R subgroup). The control group was anesthetized for 60 min by zoletil without administration of Ringer solution and furosemide, and the I group was anesthetized and overdistended for 60 min without reperfusion. After this, the rats were sacrificed and the bladders were extirpated. The bladder dome was maintained overnight in 10% formaldehyde solution and embedded in paraffin for histological studies. The remaining bladder tissue was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80℃ until processing. The animal experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Clinical Research Institute at the Seoul National University Hospital (AAALAC accredited facility) (IACUC number: 08-0259).

Detection of apoptosis

For detection of apoptosis, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-medited dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) method was used. Briefly, 5 µm thick bladder tissue sections were deparaffinized and re-hydrated in graded series of xylene and ethanol. Then, the slides were pretreated with 20 µg/mL proteinase K and quenched in 3% hydrogen peroxidase in PBS at room temperature for 5 min. After the equilibration, all sections were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37℃ for 1 hr with a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme. The reaction stopped and then the slides were incubated with an anti-digoxignenin-peroxidase conjugate at room temperature for 30 min. After stained by 0.05% diaminobenzidine in staining buffer, the color development was monitored under the microscope. When the dark brown apoptotic bodies were detected, the slides were counterstained in 0.5% methyl green for 10 min. The slides were then washed with 100% N-butanol, and mounted. In each slide, three high-power (×400) fields were randomly selected and the apoptotic index was expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells relative to the number of total cells in a given area (non-apoptotic nuclei plus apoptotic cells).

Western blot analysis

After bladder tissues were homogenized in an ice-cold lysis buffer, whole cell homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g, 4℃ for 20 min and the supernatants were collected. After quantitation of protein concentration, equal amounts of proteins (20-50 µg) were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 1 hr at room temperature, and incubated overnight at 4℃ with primary antibodies (poly [ADP-ribose] PAR, Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA; caspase 3, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA; mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Bcl-2 and Bax, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, diluted 1:1,000, respectively). Membranes were then incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) for 2 hr at room temperature, and visualized using the ECL detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The results of western blots were quantified by densitometry using Bio-Rad imaging software Quantity One 4.6.2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means±SD. Because of the modest sample size, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to analyze the total groups, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was conducted to compare between two groups. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Detection of apoptosis

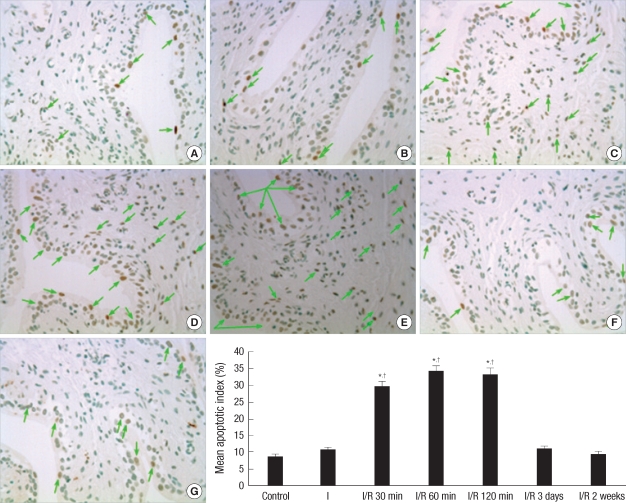

At 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min following bladder emptying, tissue sections from the I/R group exhibited a significant increase in the number of TUNEL positive cells than the controls. However, compared to the control group, there was no statistical difference in the number of TUNEL positive cells in the I group, I/R groups at 3 days and 2 weeks after bladder emptying (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Detection of apoptosis: Representative micrographs show TUNEL positive cells as black-brown (magnification ×400), that are indicated by using arrows. Bar graphs show quantitative image analysis. The apoptotic index represents the percent of apoptotic cells within the total number of cells in a given area. *P<0.01 vs control group; †P<0.01 vs ischemia only group. (A): Control group; (B): Overdistension without reperfusion (ischemia only group, I); (C)-(G): Overdistension with reperfusion for 30 min, 60 min, 120 min, 3 days and 2 weeks, respectively (ischemia/reperfusion group, I/R).

Western blot analysis

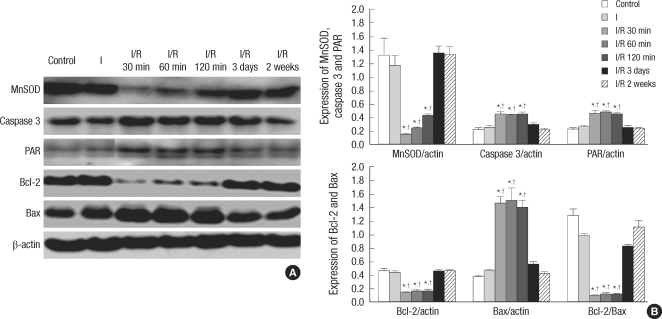

Western blot analysis of the expression of MnSOD, caspase 3, Bcl-2 and Bax and amounts of PAR showed time-dependent changes. Expression of MnSOD significantly decreased in the I/R group at 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min after bladder emptying compare to the control group, and began to recover thereafter. Expression of caspase 3 significantly increased in the I/R group at 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min after bladder emptying compared to the control group, and significantly reduced to the control level at 3 days and 2 weeks after bladder emptying. When compared to the control group, the I/R group showed significant decrease in Bcl-2 expression and significant increase in the Bax expression at 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min after bladder emptying. As a result, the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax was significantly reduced. The expression of Bcl-2 and Bax, and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax recovered to the control level at 3 days and 2 weeks after bladder emptying. On the other hand, the amounts of PAR (a marker of PARP activity) significantly increased at 30 min, 60 min, and 120 min after bladder emptying compared to the control group. Three days and 2 weeks after bladder emptying in the I/R group, there were no statistical difference in the expression of MnSOD, capase 3, Bcl-2 and Bax and the amounts of PAR between the I group and the control group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis: Representative western blot shows expression of MnSOD, caspase 3, PAR, Bcl-2 and Bax. Bar graphs depict quantitative analysis for each protein expression in the bladder. The expression of each protein was normalized to β-actin. *P<0.01 vs control group; †P<0.01 vs ischemia only group. I, overdistension without reperfusion (ischemia only group); I/R 30 min-2 weeks, overdistension with reperfusion for 30 min, 60 min, 120 min, 3 days and 2 weeks, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis is an important element in maintaining the structural integrity and homeostasis of organisms. Although bladder apoptosis is frequently associated with AUR, the time course of the bladder apoptosis and the underlying mechanism of apoptosis have not been well established. In the present study, we found that bladder apoptosis was significantly increased in earlier time points following bladder overdistension and subsequent emptying. Another important finding was that bladder apoptosis induced by AUR after acute BOO and subsequent bladder emptying was associated with decreased MnSOD expression, increased PARP activity and imbalance between proand anti-apoptotic factors.

AUR secondary to acute BOO is a clinical and experimental syndrome characterized by bladder dysfunction and apoptotic injury of the bladder (11, 16). Ischemia/reperfusion injury and subsequent oxidative stress are believed to play a central role in AUR induced bladder dysfunction, in addition to several other factors such as bladder overdistension and ischemia (8, 16).

Oxidative stress is often defined as imbalance between free radical productions and antioxidant capability. It has been demonstrated that nitric oxide and superoxide generated during the process of I/R, which can react to form the powerful nitrating agent peroxynitrite (17). Peroxynitrite as a potent oxidizing and nitrating agent has been shown to cause numerous injurious events, such as lipid peroxidation, reduction in antioxidant defenses and inactivation of enzymes that may adversely affect their function and signal transduction processes (18, 19). Impaired response to oxidative stress antioxidative proteins, include MnSOD, heat shock proteins (HSPs), and IGF-1 (20). MnSOD is the major antioxidative enzyme in the mitochondria, which catalyzes superoxide.

Numerous studies have shown that MnSOD was essential for life, because homozygous MnSOD knockout mice exhibited myocardial and liver injury and endothelial dysfunction (21-23), whereas overexpression of MnSOD reduced I/R-related damage (24, 25). Therefore a loss of MnSOD activity during I/R appears to be related to tissue injury. On the other hand, MnSOD is a major mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme involved in the suppression of apoptosis, via regulation of the Bcl-2 family proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bax (26, 27). In our study, western blot analysis showed decreased MnSOD expression was parallel to bladder apoptosis. In addition, western blot analysis also showed decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased Bax and caspase-3 expression. These results indicate that downregulation of MnSOD expression and imbalance of Bcl-2 family proteins expression play a critical role in the development of bladder apoptosis following AUR and subsequent reperfusion.

Recent studies have demonstrated that increase ROS generation following I/R injury increased PARP activity and caused damage in several organs, such as brain, kidney and the heart (12-14). Therefore we examined whether activity of PARP is increased in the bladder after AUR and subsequent reperfusion. Western blot analysis showed a significant increase in activation of PARP in earlier time points after bladder overdistension and subsequent emptying. The present study indicates that activation of PARP may participate in the development of bladder apoptosis following AUR and subsequent reperfusion. However, how PARP activation induces bladder apoptosis remains unclear. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism.

We did not investigate whether inhibition of PARP could attenuate bladder apoptosis following bladder I/R injury. This is the main limitations of our study. Since PARP inhibition counteracts several organs damage caused by I/R injury, such as brain, kidney and the heart, further studies are required to determine whether inhibition of PARP could attenuate bladder apoptosis.

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide evidence that bladder apoptosis induced by AUR after acute BOO and subsequent bladder emptying is associated with decreased MnSOD expression, increased PARP activity and imbalance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors. These results add to our understanding of the pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms involved in bladder damage induced by I/R injury after acute BOO and subsequent bladder emptying.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grant 06-2008-1670 from the Handok Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Park JS, Lee CY, Lee W, Lee JZ. The effect of terazosin on the histological changes of rat bladder after partial outlet obstruction. J Korean Continence Soc. 2006;10:106–115. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM. The Reten-World survey of the management of acute urinary retention: preliminary results. BJU Int. 2008;101(Suppl 3):27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan SA, Wein AJ, Staskin DR, Roehrborn CG, Steers WD. Urinary retention and post-void residual urine in men: separating truth from tradition. J Urol. 2008;180:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee TM, Su SF, Suo WY, Lee CY, Chen MF, Lee YT, Tsai CH. Distension of urinary bladder induces exaggerated coronary constriction in smokers with early atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2838–H2845. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu HJ, Lin BR, Lee HS, Shun CT, Yang CC, Lai TY, Chien CT, Hsu SM. Sympathetic vesicovascular reflex induced by acute urinary retention evokes proinflammatory and proapoptotic injury in rat liver. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1005–F1014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00223.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen SS, Chen WC, Hayakawa S, Li PC, Chien CT. Acute urinary bladder distension triggers ICAM-1-mediated renal oxidative injury via the norepinephrine-renin-angiotensin II system in rats. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108:627–635. doi: 10.1016/s0929-6646(09)60383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu S, Saito M, Kinoshita Y, Kazuyama E, Tamamura M, Satoh I, Satoh K. Acute urinary retention and subsequent catheterization cause lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in the bladder: preventive effect of edaravone, a free-radical scavenger. BJU Int. 2009;104:713–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratslavsky G, Kogan BA, Matsumoto S, Aslan AR, Levin RM. Reperfusion injury of the rat bladder is worse than ischemia. J Urol. 2003;170:2086–2090. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000092144.48045.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohnishi N, Liu SP, Horan P, Levin RM. Effect of repetitive stimulation on the contractile response of rabbit urinary bladder subjected to in vitro hypoxia or in vitro ischemia followed by reoxygenation. Pharmacology. 1998;57:139–147. doi: 10.1159/000028235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juan YS, Chuang SM, Kogan BA, Mannikarottu A, Huang CH, Leggett RE, Schuler C, Levin RM. Effect of ischemia/reperfusion on bladder nerve and detrusor cell damage. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9492-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong SK, Son H, Kim SW, Oh SJ, Choi H. Effect of glycine on recovery of bladder smooth muscle contractility after acute urinary retention in rats. BJU Int. 2005;96:1403–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu R, Gao M, Yang ZH, Du GH. Pinocembrin protects rat brain against oxidation and apoptosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion both in vivo and in vitro. Brain Res. 2008;1216:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu HH, Hsiao TY, Chien CT, Lai MK. Ischemic conditioning by short periods of reperfusion attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion induced apoptosis and autophagy in the rat. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:19. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sodhi RK, Singh M, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Protective effects of caspase-9 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors on ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial injury. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildirim A, Onol FF, Haklar G, Tarcan T. The role of free radicals and nitric oxide in the ischemia-reperfusion injury mediated by acute bladder outlet obstruction. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11255-007-9216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu HJ, Chien CT, Lai YJ, Lai MK, Chen CF, Levin RM, Hsu SM. Hypoxia preconditioning attenuates bladder overdistension-induced oxidative injury by up-regulation of Bcl-2 in the rat. J Physiol. 2004;554:815–828. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mladenka P, Simunek T, Hubl M, Hrdina R. The role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in cellular iron metabolism. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:263–272. doi: 10.1080/10715760500511484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dohare P, Varma S, Ray M. Curcuma oil modulates the nitric oxide system response to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi C, Zalawadia R, Balaraman R. Nebivolol reduces experimentally induced warm renal ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Ren Fail. 2008;30:921–930. doi: 10.1080/08860220802353900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawler JM, Kwak HB, Kim JH, Suk MH. Exercise training inducibility of MnSOD protein expression and activity is retained while reducing prooxidant signaling in the heart of senescent rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1496–R1502. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90314.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Remmen H, Qi W, Sabia M, Freeman G, Estlack L, Yang H, Mao Guo Z, Huang TT, Strong R, Lee S, Epstein CJ, Richardson A. Multiple deficiencies in antioxidant enzymes in mice result in a compound increase in sensitivity to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1625–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohashi M, Runge MS, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. MnSOD deficiency increases endothelial dysfunction in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2331–2336. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000238347.77590.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessova IG, Ho YS, Thung S, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol-induced liver injury in mice lacking Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase. Hepatology. 2003;38:1136–1145. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saba H, Batinic-Haberle I, Munusamy S, Mitchell T, Lichti C, Megyesi J, MacMillan-Crow LA. Manganese porphyrin reduces renal injury and mitochondrial damage during ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SP, Hoffmeyer MR, Sharp BR, Ho YS, Lefer DJ. Role of intracellular antioxidant enzymes after in vivo myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H277–H282. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00236.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma DR, Sunkaria A, Bal A, Bhutia YD, Vijayaraghavan R, Flora SJ, Gill KD. Neurobehavioral impairments, generation of oxidative stress and release of pro-apoptotic factors after chronic exposure to sulphur mustard in mouse brain. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;240:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Z, Lin S, Wu W, Tan H, Wang Z, Cheng C, Lu L, Zhang X. Ghrelin prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB pathways and mitochondrial protective mechanisms. Toxicology. 2008;247:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]