Abstract

The incidence of acute hepatitis in syphilis patient is rare. First of all, our patient presented with hepatitis comorbid with thrombocytosis. To our knowledge, this is only the second report of syphilitic hepatitis with thrombocytosis. The 42-yr-old male complained of flulike symptoms and skin eruptions on his palms and soles. Laboratory findings suggested an acute hepatitis and thrombocytosis. Serologic test results were positive for VDRL. He recovered from his symptoms and elevated liver related enzymes with treatment. Because syphilitic hepatitis can present without any typical signs of accompanying syphilis, syphilis should be considered as a possible cause in acute hepatitis patients.

Keywords: Hepatitis; Syphilis, Cutaneous; Thrombocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Although we believe that syphilis is considered to be a controllable disease in the antibiotic era, its incidence has been increasing in those engaging in high-risk behaviors recently (1-3). Seven cases described by Hahn in 1943 were the first in which hepatitis was related to syphilis. Since then, about 100 cases have been reported globally (4), but there are only two case reports in the Korean literature (5, 6). Syphilis is a systemic disease and presents a spectrum of clinical symptoms. It cannot be diagnosed at presentation if the patient does not have typical skin lesions, such as chancres on the external genitalia or syphilids on the palms and soles. Recently, we diagnosed a syphilitic hepatitis case with thrombocytosis. The incidence of acute hepatitis in syphilis patient has been rare, moreover, this case had also thrombocytosis. This heterosexual, immunocompetent patient presented symptoms that included jaundice and typical syphilids.

CASE REPORT

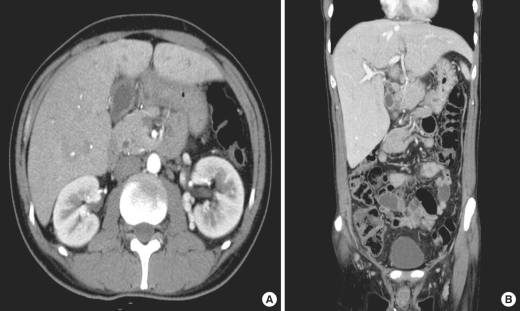

On 21 May 2009, a 42-yr-old male patient visited our hospital because of malaise and jaundice. He had been working as an office manager of a trading company in China for two years. Two mild fever, and one month before examination, he felt unusual fatigue and jaundice. Twenty days before examination, he had been informed that his acute hepatitis was unusual because he had no hepatitis A, B, or C viral markers. He took herbal medication and received acupuncture in China under the diagnosis of acute hepatitis of unknown origin. His symptoms improved under herbal medication, but remained. He returned to Korea for treatment of the acute hepatitis. He had no other symptoms except for scanty whitish phlegm. He had been healthy until the recent illness. He was not currently on medication, was not an injecting drug abuser. He did not smoke nor drink alcohol. He had received no blood transfusion. He had been married for seven years, but had lived alone in China for two years. He was well oriented and his vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed icteric sclera and tender hepatomegaly. No mucous membrane lesions nor lymphadenopathy were present and he was afebrile. Cutaneous manifestations consisted of macular and papular lesions, about 0.5 cm in diameter, localized on the trunk, palms, and soles (Fig. 1). Genital examination revealed no lesions nor ulcers. Lymph nodes were not palpable in the neck, axillary, or inguinal areas. Laboratory tests showed the following: alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 2,974 IU/L, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 1,755 IU/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 89 IU/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 119 IU/L, total bilirubin 8.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.9 mg/dL, creatinine 0.8 mg/dL, albumin 2.4 g/dL, total protein 9.2 g/dL, white blood cell (WBC) 13,600/µL, hemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, platelets 752,000/µL, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.06, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) was positive with a titer >1:1,024, and his fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) was reactive. A hepatitis panel including IgM anti-HAV, HBsAg, and anti-HCV, antinuclear antibody, ceruloplasmin, copper, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were all nonreactive. Computerized tomography didn't show any evidence of bile duct obstruction. It showed also mildly enlarged liver, nonspecifically enlarged lymph nodes at the porta hepatis area, and thickened gall bladder wall (Fig. 2). Chest radiography was normal.

Fig. 1.

Photographic findings of syphilid. There are multiple erythematous macules and flat-topped papules with scales on both palms (A), soles (B), and the trunk (C).

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic findings. (A) Horizontal, (B) Coronal section. They show no dilatation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, but the gall bladder wall was thickened.

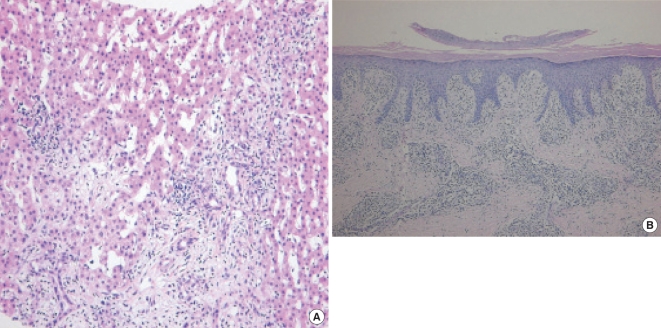

Liver biopsy revealed portal-to-portal or portal to central zone bridge necrosis, and widening by lymphocyte infiltration, accompanied by intracanalicular and intracellular cholestasis. These findings were compatible with acute hepatitis (Fig. 3A). A modified Warthin-Starry stain was negative for spirochetes. Skin biopsy revealed a perivascular mixed-cell infiltrate of prominent plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes around a blood vessel that contained swollen endothelial cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Findings of tissue biopsy findings. (A) Liver. Stromal edema is observed around the portal tract. Both focal necrosis and infiltration of lymphocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils in the lobule are also observed (periodic acid-Schiff stain, ×200). (B) Skin. The epidermis shows parakeratosis, acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes. A dense perivascular inflammatory infiltrate is seen in A the dermis (H&E, ×100).

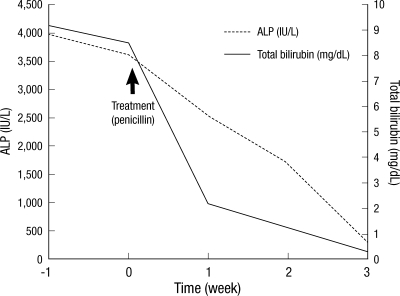

The patient was treated with weekly intramuscular benzathine penicillin, 2,400,000 U, for a total of three doses. One week after treatment, his fatigue and rash were markedly improved. Three weeks after treatment, ALP was 288 IU/L, total bilirubin was 0.3 mg/dL (Fig. 4) and four weeks after treatment, the VDRL titer was down to 1:64. He did not develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Positive serologic tests and a prompt response to penicillin treatment confirmed the diagnosis of syphilitic cholestatic hepatitis.

Fig. 4.

Clinical course after the treatment. The serum level of total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase has significantly declined after the benzathine penicillin treatment. ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

DISCUSSION

Described by William Osler as the 'great imitator' (7), syphilis shows a wide variety of clinical aspects. Although liver involvement has been known since 1918 (8), it is still uncommon and thus can be easily overlooked. In addition, atypical symptoms and a skin rash with other organ involvement makes syphilis difficult to distinguish from autoimmune disease or viral hepatitis (9).

The clinical manifestations of syphilitic hepatitis are likely to be subsequent to the dissemination of treponema from the site of the primary lesion to the liver (10, 11). A generalized rash and hepatomegaly are often present. Laboratory findings include a modest increase in transaminases and bilirubin, but a marked increase in ALP and GGT (11). While this cholestatic pattern is more usual, some cases have shown predominantly hepatocellular damage (12). We could find the predominantly cholestatic pattern in our patient.

Reports of thrombocytosis accompanying secondary syphilis are uncommon and are mostly limited to neonatal patients. Platelet abnormalities in this setting are largely thrombocytopenia (13). There can be of any causes of thrombocytosis. Elevated platelet counts are more often part of the body's response to acute or chronic insults, such as acute infection, malignant disease, hemorrhage, or iron deficiency. We believe that thrombocytosis is related to secondary syphilis in this patient because it normalized with treatment (14).

Liver biopsy is often nonspecific, typically demonstrating periportal lymphocytic infiltration with focal necrosis of hepatic cells around central veins, portal areas, and lobules. Our case showed these pathological findings with intracellular cholestasis and eosinophilic infiltration of the portal area.

The presence of spirochetes in liver tissue is diagnostic, but difficult to demonstrate. Treponemas are observed in about half of the reported cases (15-17). Although one reported adult case developed fulminant hepatitis, most cases show complete clinical and laboratory recovery after benzathine penicillin G treatment (18).

Although the mechanism of secondary syphilitic hepatitis has not yet been elucidated, anal intercourse between homosexual persons has been proposed as a risk factor. This is thought to lead to T. pallidum in the portal circulation. An anorectal or penile lesion could not be detected in our patient, and he denied any homosexual intercourse during his lifetime.

The diagnosis of syphilitic hepatitis can be made by positive serologic tests and the exclusion of other hepatitis etiologies. Although it is not commonly seen, it should be considered as a possible cause of acute hepatitis.

Footnotes

Supported by the research grant of the Chungbuk National University in 2009.

References

- 1.Agrawal NM, Sassaris M, Brooks B, Akdamar K, Hunter F. The liver in secondary syphilis. South Med J. 1982;75:1136–1138. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crum-Cianflone N, Weekes J, Bavaro M. Syphilitic hepatitis among HIV-infected patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:278–284. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullick CJ, Liappis AP, Benator DA, Roberts AD, Parenti DM, Simon GL. Syphilitic hepatitis in HIV-infected patients: a report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:e100–e105. doi: 10.1086/425501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn RD. Syphilis of the liver. Am J Syph. 1943;27:529–562. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seong JY, Kwon SY, Park CH, Chung NS, Kim YN, Kwon OS, Kim SS, Choi DJ, Kim JH. A case of syphilitic hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2005;11(3 Suppl):122S. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon HH, Woo CM, Oh HJ, Ahn KS, Cho CH, Kim YJ, Lee IH. Nephrotic syndrome, hepatitis and gastric involvement in secondary syphilis. Korean J Nephrol. 2004;23:152–157. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridruejo E, Mordoh A, Herrera F, Avagnina A, Mando OO. Severe cholestatic hepatitis as the first symptom of secondary syphilis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1401–1404. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000042237.40205.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warthin AS. The new pathology of syphilis. Am J Syphil Gonor Vener Dis. 1918;2:425–452. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noto P, Nonno FD, Licci S, Chinello P, Petrosillo N. Early syphilitic hepatitis in an immunocompetent patient: really so uncommon. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:65–66. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherlock S. The liver in secondary (early) syphilis. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1437–1438. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197106242842513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tramont EC. Treponema pallidum. In: Mandel GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 2474–2489. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozaki T, Takemoto K, Hosono H, Miyagawa K, Akimoto S, Nishimura N. Secondary syphilitic hepatitis in a fourteen-year-old male youth. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:439–441. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200205000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KY, Kim SH. Hematological aspects of congenital syphilis. Yonsei Med J. 1976;17:142–150. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1976.17.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn TD. Thrombocytosis in a patient with secondary syphilis. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:1241–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlossberg D. Syphilitic hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:552–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young MF, Sanowski RA, Manne RA. Syphilitic hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehér J, Somogyi T, Timmer M, Józsa L. Early syphilitic hepaititis. Lancet. 1975;2:896–899. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo JO, Harrison RA, Hunter AJ. Syphilitic hepatitis resulting in fulminant hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation. J Infect. 2007;54:e115–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]