Abstract

Considering the adsorption of counterions on an isolated polyelectrolyte (PE) chain and using a variational theory, phase boundaries and the critical point for the first-order coil-globule transition are calculated. The transition is induced cooperatively by counterion adsorption and chain conformations and the calculation is done self-consistently. The size of the PE chain is a single-valued function of charge. The discontinuous transition of the coil size is accompanied by a discontinuous transition of the charge. Phase boundaries for the coil-globule transitions induced by both Coulomb strength (inverse temperature or dielectric constant) and ionic strength (salt) show that the PE chain collapses at a substantially lower Coulomb strength in the presence of salt. In the expanded state of the coil, an analytical formula is derived for the effective charge of the chain for conditions where the coupling between chain conformations and counterion adsorption is weak. In general, the dielectric heterogeneity of the solvent close to the polymer backbone is found to play a crucial role in the charge regularization and the chain collapse.

I. Introduction

The net charge of a polyelectrolyte (PE) chain in salty aqueous solutions is the most fundamental albeit elusive entity faced in systems containing charged polymers. The various manifestations of the charged nature of the polymer, whether m-RNA, ss- or ds-DNA, proteins, polysaccharides, or synthetic analogs such as polystyrene sulfonates, and the ways in which they fold conformationally and move in solutions depend crucially on their effective charge determined by the degree of dissociation of the charged groups. These conformational fluctuations of PE chains under external stimuli such as temperature, solvent quality, pulling force, or salt are of critical importance to numerous biological and synthetic processes. In addition, the net effective charge of PE chains, its significance in various contexts such as conductivity measurements or titration curve experiments, and related concepts of strong and weak polyelectrolytes (or quenched and annealed PE, respectively) continue to pose complexity in the understanding of phase behaviors in PE systems. Study of the effective charge, size of the polymer, and their mutual dependency in polyelectrolyte systems is thus important both from fundamental and applied points of view.

In generic conditions, a charged chain (PE) in a good solvent assumes dimensions much larger1–5 than an uncharged self-avoiding-walk (SAW) chain due to the electrostatic repulsion between like-charged monomers. This repulsive force resists the collapse of the PE in a poor solvent, but only up to a certain degree of hydrophobicity, beyond which it shrinks to dimensions way below the Gaussian value6–9, similar to neutral chains. Additionally, the PE always has its counterions some of which adsorb (i.e., condense) on the monomers and modulate the effective charge depending on the ambient conditions. When the net charge is reduced due to counterion adsorption, the electrostatic resistance to polymer collapse decreases, causing an easier collapse. Therefore, in generic circumstances a self-consistent procedure is necessitated to calculate the size and the effective charge of the PE molecule. The net charge results from an optimization between electrostatic binding energy and translational entropy, and, depending on the physical conditions, it may or may not be sensitively dependent on the polymer size. It is also worthwhile to explore conditions at which the coupling between the charge and the size of a polymer may turn out to be not mutual (for example, size depends on charge but not the other way around, or vice versa).

A number of theories10–15 addressed the size dependency of a PE chain (or a PE gel16) on its effective charge, which is taken as a fixed parameter independent of its size. As discussed above, a fixed finite charge is incompatible to a collapsed PE chain as it leads to a considerable electrostatic repulsive energy penalty. The first model17–19 that attempted at a self-consistent calculation of the size and charge of isolated PE chains assumed a partitioning of the dissociated (free) ions into two domains - one within and the other outside the radius of gyration (Rg) of the PE - rendering it to be a three-state model. However, the conformational entropy of the chain and its changes with experimental conditions were not included. Concurrently, a variable PE charge was addressed20 within the Oosawa model assuming rod-like chains which, however, do not represent flexible polymers with appropriate conformational changes. Earlier, a variational theory21 had analyzed the collapse due to counterion correlations in good solvents, but failed to include the counterion adsorption effects which are required to address the experimental trends in the expanded state. The mechanism of correlation induced collapse in this theory dealing with good solvents differs significantly to that in a poor solvent, in which the collapse occurs due to hydrophobic effects. Further, this theory predicted an expansion of the coil with a decrease in temperature, just before it collapses into a globule. This prediction is not supported by experiments. A very recent computer simulation22 has predicted the degree of ionization to increase with the salt concentration, which is in stark contradiction to previous1–4 results. Neglect of the entropy of both free counterions and the polymer chain have possibly led to this anomaly. It is therefore evident that a theory that captures faithfully counterion adsorption, intra-chain electrostatic repulsion, and polymer conformational changes in a self-consistent way is desirable. Poor solvent conditions are expected to lend further complexities.

Experiments23–28 and simulations29,30 have indisputably demonstrated that a PE chain at a specific poorness of the solvent collapses to a globule. However, the stability of a plausible intermediate pearl-necklace phase31–39, made of globules and elongated chain parts co-existing in a single chain, remains a controversial29,30 issue. It is still unanswered whether experimentally observed pearl-necklace structures35,36 are stable phases or kinetically trapped configurations. Simulations with explicit solvent fail to find29,30 stable pearl-necklace structures. It is evident that if a collapsed globule collects all its counterions to minimize its charge, the necklace structure will be absent. Therefore, it is imperative to understand what dictates the degree of counterion adsorption both in the expanded and collapsed states of a PE chain.

In this article, we present a theory which addresses the cooperativity of the counterion adsorption and solvent poorness. By self-consistently considering the counterion adsorption and chain conformations5,40, with the use of a double minimization (over the degree of ionization and the coil size) procedure, we first provide numerical results for the coil-globule transition of a flexible polyelectrolyte chain. The key feature of the calculated phase boundaries for the coil-globule transition is that the collection of counterions by the collapsing polymer occurs in tandem with the polymer collapse, and that there is a unique mapping between the effective charge and the average coil size. Our theory emphasizes that for the general situation of polyelectrolyte chains in polar media, with or without salt, it is crucial to simultaneously account for the dissociation equilibrium (between the ionized monomer and the ion-pair formed on the monomer) and the local dielectric constant mediating this equilibrium. Within this concept, the difference between “quenched”41 (in which the overall charge in the chain is fixed) and “annealed” (charge is variable) polyelectrolytes ceases to exist, especially in the aqueous solvents, due to an unavoidable occurrence of counterion adsorption. Another important feature of our analysis is that the temperature controls both the solvent quality and the Coulomb strength concurrently.

The theory presented here is a generalization of the original theory5 to deal with the coil-globule transition of the chain in a poor solvent by including an additional three-body term in the free energy of the chain, in order to stabilize the hydrophobic collapse. Our treatment is distinct from other approaches reported in the literature as follows. In contrast to the previous model with self-consistent minimization17–19, our model considers the variational chain free energy which explicitly accounts for the entropic part of the chain fluctuations and describes the electrostatic energy due to the repulsion among monomers more accurately. The difference between the present theory and the apparently similar variational analysis21 is that our theory addresses polyelectrolyte collapse in poor solvents and includes the effect of counterion adsorption. As is evident from the discussion below, incorporation of ionization equilibria mediated by the local dielectric function leads to significantly different results from the case21 of polymer collapse in good solvents with uniform dielectric constant. Another early treatment41 considered minimization of free energy with respect to only the charge, but missed the coupling with polymer conformations. Finally, our model is fundamentally different from the Manning condensation theory42,43. Our self-consistent method is applicable for flexible polymers, and it accounts for the interplay between chain conformations and counterion adsorption, as well as for the “oily” chemical nature of the polymer backbone.

Based on the numerical calculations, we have followed the quantitative details of different contributions to the free energy arising from chain entropy, counterion adsorption energy, translational entropy of small ions, and fluctuations of small ion density distributions at different conditions. This effort was undertaken in order to possibly derive analytical expressions for the effective charge and the polymer size as the coil-globule transition is taking place. It turns out that all of these contributing terms contribute more or less equally near the critical point and in the transition region, signaling the importance of the coupling between the charge and chain conformations. However, for conditions away from the coil-globule transition and in the swollen state, the free energy contribution from chain conformations becomes smaller than the other contributions. This has enabled a derivation of an analytical formula for the effective charge of a swollen polyelectrolyte chain as a function of the various parameters of the system. This analytical expression for the effective charge is in good agreement with the numerical results for a surprisingly wide range of physical conditions, as long as the chain is swollen. This simplification breaks down as the transition is approached, necessitating the numerical computation of the phase boundaries by considering the cooperativity among the counterion adsorption and polymer conformations.

As summarized above, there have been several theoretical papers devoted to the collapse of a polyelectrolyte chain. The new feature of the present work is the self-consistent calculation of the synergistic cooperativity between polymer conformations and counterion adsorption. The polymer charge is allowed to self-regulate. In our model, the equilibrium of counterion adsorption is mediated by the mismatch between the local and bulk dielectric constants, translational entropy of the dissociated counterions and polymer conformations. The main result is the simultaneous occurrence of discontinuous polymer collapse and counterion adsorption, which control each other mutually.

II. Theory

The total free energy of the system consisting of an isolated flexible PE chain with ionizable monomers, counterions, and the added salt ions (all monovalent) in high dilution is taken to be5 F = ΣiFi where,

| (2.1) |

with the contributions being due to, respectively, the entropy of mobility along the chain backbone of adsorbed counterions (F1), the translational entropy of the mobile ions (F2) (including both free counterions from the polymer and the salt ions), fluctuations in densities of all mobile ions (F3, as in the Debye-Hückel theory), adsorption (Coulomb) energy of the bound counterion-monomer pairs (F4), and the free energy of the chain40 (F5) resulting from its connectivity (conformational entropy) (first term in F5), the two-body interaction (second term in F5), three-body interaction (third term in F5), and screened electrostatic interactions between charged monomers (fourth term in F5). Here fm ≡ Nc/N, α ≡ M/N, with N, Nc and M being the numbers, respectively, of monomers, of ionizable monomers, and of adsorbed counterions, kB the Boltzmann constant, and T the absolute temperature. , and with ns, l0 and Ω being, respectively, the number of salt cations, the Kuhn step length (length of a monomer for a fully flexible polymer), and the volume of the system.

| (2.2) |

is the dimensionless inverse Debye length, where κ̃ = κl0. The dielectric mismatch parameter δ is defined as δ = (εl0/εld) with εl, and d being, respectively, the local dielectric constant5,44–46, and the ion-pair separation. Further, with, l̃1 = l1/l, the effective expansion factor5,40 and f ≡ (Nc − M)/N = fm − α, the effective charge fraction. Θ0(a) = 2/15(a ≪ 1),1/3a(a ≫ 1) is a cross-over function5,40 of a ≡ κ̃2Nl̃1/6. The effect of ion-pairs5 that reduces the two-body interaction parameter only slightly without significantly affecting the phase boundaries is ignored in this paper.

We further define a dimensionless reduced temperature47 t as

| (2.3) |

with

| (2.4) |

as the dimensionless Bjerrum length which contains the information of the dielectric constant of the solvent, the absolute temperature, and the Kuhn step length. Here, e, ε0, and ε are the electron charge, vacuum permittivity, and the solvent dielectric constant, respectively. The two-body interaction parameter w is related to the chemical mismatch parameter χ through w = 1−2χ, and χ is defined as47

| (2.5) |

where aχ is a chemical mismatch coefficient. Therefore, using Eqs. (2.3) and (2.5),

| (2.6) |

where, using Eq. (2.4),

| (2.7) |

The chemical mismatch coefficient aχ can thus be related to the theta temperature Θt used in gel physics48 using Eq. (2.7). The three-body interaction parameter w3 is related to chain stiffness49 and is taken as temperature-independent. A dimensionless reduced temperature allows one to describe the phase transition in general terms, which include solvents with varying dielectric constant and temperature. The unique feature of the present calculation is to take temperature (or the reduced temperature t) as the only independent variable, thus rendering w and lB as dependent functions through, respectively, the relations w = 1 − aχ/(10πt), and l̃B = 1/4πt. Correspondingly, the theta-temperature (at which w vanishes) and the dielectric constant of the solvent (l̃B being inversely proportional to the product of temperature and dielectric constant) form the reference variables in experiments in which temperature is varied. The calculated phase diagrams given below are thus representations of phase transitions with the chemical mismatch coefficient aχ as the reference variable, and the reduced temperature t a general experimental variable. A special case of this general analysis would be to consider a polymer of type NaPSS in water. We take this type as a uniformly charged flexible polyelectrolyte in polar solvents like water. It is evident that collapse is unlikely for polyelectrolyte chains of type NaPSS in dilute solutions of water at room temperature (t = 0.02653) without additional salt, but is possible28 in a solvent with much lower dielectric constant (which reduces t at a fixed absolute temperature).

The above choice of the parameter χ (Eq. (2.5)) is only to illustrate the general nature that χ and lB are inter-dependent and that when the temperature is changed both χ and lB change. Other choices for χ may be made that are appropriate for the particular polymer-solvent systems. It appears superficially from the definition of lB (Eq. (2.4)) that a decrease in ε is equivalent to a reduction in temperature. In reality specifically for aqueous systems, the dielectric constant itself depends on temperature and as a consequence the product of dielectric constant and temperature is only weakly dependent on temperature. Furthermore, due to the appearance of temperature in the definition of χ (without dielectric constant) and in the definition of lB (with dielectric constant), the temperature-dependent ε and temperature influence the polymer collapse separately.

III. Results and Discussion

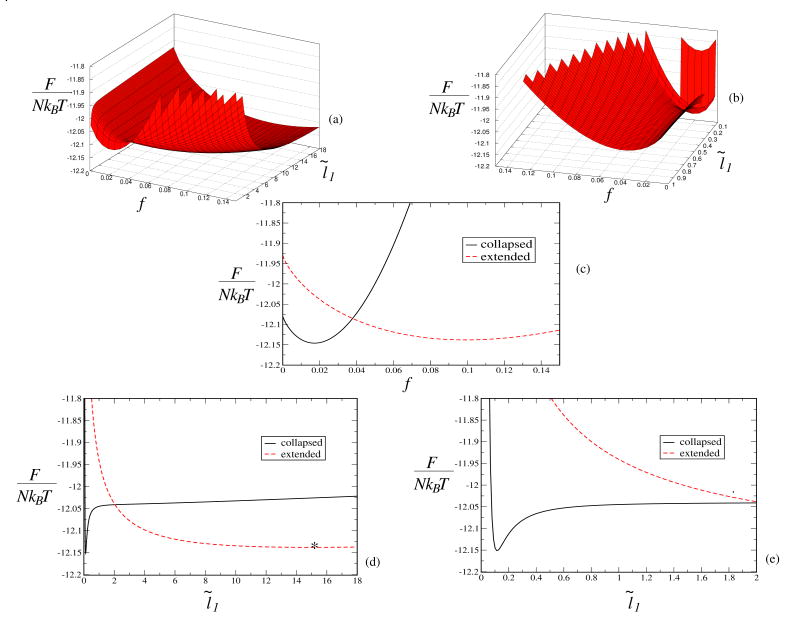

Generally, F = Σi Fi must be minimized self-consistently with respect to both f and l̃1 to obtain the equilibrium values of the variables. Minimization of the free energy in the presence of multiple terms is most often difficult to perform analytically, and numerical solutions remain the only option. The degree of variation of the individual terms with the minimizing variables rather than their absolute weights is the determining factor. Therefore, we have minimized the total free energy (sum of all five components) numerically with respect to both variables (f and l̃1). To gain insight into the collapse transition process in which the minimum free energies of the collapsed and expanded states are equated, we have plotted the total free energy (F/NkBT) as a function of the effective degree of ionization (f) and the expansion factor (l̃1) of the chain at a condition close to a collapse transition (Fig. 1). The two minima correspond to f, l̃1 = 0.017, 0.12 (the collapsed state) and f, l̃1 = 0.10, 15.03 (the expanded state), respectively. (a) and (b) represent 3d surface plots whereas (c), (d), and (e) represent 2d plots of F as a function of either f or l̃1. In (a) two minima are evident, although the sharp jump in F close to the collapse minimum, shown in detail in (b), is ignored for clarity. In the 2d plots, F is plotted against either f or l̃1 keeping the other variable fixed at its value at the collapsed chain minimum (black) and extended chain minimum (red), respectively. The value of l̃1 for the extended minimum is obtained numerically and is represented by a star in (d). In (e), part of (d) is magnified to show the free energy minimum corresponding to the collapsed state. So there are indeed two minima in the free energy with slightly different values at conditions close to a collapse transition, and small changes in the external parameters make either of them slightly lower leading to a transition either way. As closed-form analytical expressions for f and l̃1 are always desirable, we have analyzed the numerical values of the various contributions to the free energy in an effort to obtain simpler formulas. The numerical results and the approximate analytical formulas are presented in the following subsections. As shown below, while analytical formulas, with good agreement with numerical results, can be obtained for swollen coils away from the coil-globule transition, it turns out to be necessary to perform numerical computation to adequately capture the cooperative coupling among the counterion adsorption and shrinkage of coil size.

Fig. 1.

Plot of the total free energy (F/NkBT) vs the effective degree of ionization (f) and the expansion factor (l̃1) close to a collapse transition. The two minima correspond to f, l̃1 = 0.017, 0.12 (the collapsed state) and f, l̃1 = 0.10, 15.03 (the expanded state), respectively. (a) and (b) represent 3d surface plots whereas (c), (d), and (e) represent 2d plots. In (a) two minima are evident, although the sharp jump in F close to the collapse minimum, shown in detail in (b), is ignored for clarity. In the 2d plots, F is plotted against either f or l̃1 keeping the other variable fixed at its value at the collapse minimum (black) and extended minimum (red), respectively. Note, The value of l̃1 for the extended minimum is obtained numerically and represented by a star in (d). In (e) part of (d) is magnified to show the collapse minimum.

A. Numerical results

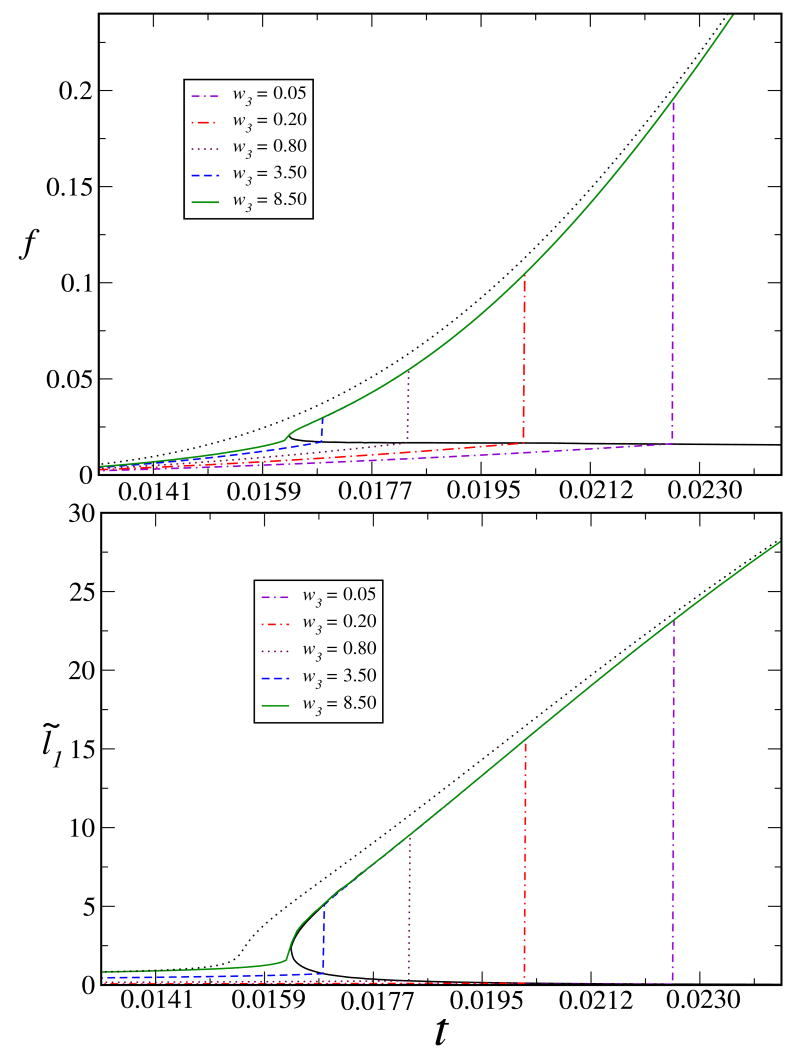

Based on the total free energy at the optimum values of f and l̃1, we have calculated the conditions for coexistence of the globular and coil states by stipulating that the total free energy of the system in these two states are the same. The coexistence curve and the critical point for the Coulomb-strength-induced (such as lower temperature or dielectric constant) collapse of a fully ionizable chain in salt-free solutions are presented in Fig. 2. The PE chain is expanded (high values of l̃1) due to inter-monomer electrostatic repulsion at higher values of the reduced temperature, i.e, for lower Coulomb strengths. At these values of t, the effective charge is high enough to maintain this repulsion which resists the collapse in a poor solvent (note, for aχ = 10/9 the solvent is poor if t < 0.0354). As the Coulomb strength is increased with lower values of t, counterions condense to reduce the effective charge. At a certain value of f corresponding to a specific Coulomb strength, the electrostatic repulsion becomes weak enough to allow a collapse. Once the collapse occurs, the chain collects the counterions to reduce its effective charge. The value for t at collapse decreases with an increasing w3 culminating at the critical point at which t* = 0.01634, , , f* = 0.020, and from t*, we get , w* = −1.164. For the special case of NaPSS in water, the Bjerrum length at room temperature (300K) is ∼ 0.75 nm, the Kuhn length (l0) is ∼ 0.25 nm, and the dielectric constant ε = 80 resulting in l̃B = 900/T and Θt = 400K. Then T* = 184.9K which implies an expanded chain conformation at room temperature at which t = 0.02653 (assuming reasonable values of w3).

Fig. 2.

Coulomb strength (inverse temperature or dielectric constant) induced collapse, phase boundaries for the chain charge and size, and the critical point of a fully ionizable polyelectrolyte chain at salt-free conditions. Fixed parameters are: N = 1000, ρ̃ = 0.0005, δ = 3.0, Ionizability fm = 1.0, aχ = 10/9, and c̃s1 = 0.0. Critical values are: t* = 0.01634 (therefore, and w* = −1.164), , , f* = 0.020. For the special case of NaPSS in water, l̃B = 900/T and Θt = 400K. Then T* = 184.9K implying expanded chain at room temperature. Dotted curves are the analytical result [Eq. (3.1)] in the expanded state.

As evident in Fig. 2, the phase boundaries of the charge (f) and size (l̃1) are similar. There can not be a coexistence of expanded and collapsed states for the same effective charge of the chain. In other words, at equilibrium the chain can have only one size for one value of its effective charge. Further, the critical size of a fully ionizable chain at salt free conditions is larger than its Gaussian value (l̃1 = 1) due to intra-chain electrostatic repulsion, whereas for a neutral chain it is smaller (l̃1* = 0.45 < 1). Gradual reduction of the ionizability (fm) leads to an increasing critical temperature and a decreasing critical size, for which the neutral chain values9 are recovered for fm = 0. The phase boundary clearly suggests that counterion condensation and chain collapse are mutually cooperative processes in the case of a varying Coulomb strength. Lowering temperature in the expanded state helps counterion adsorption which reduces the effective charge and hence the resistance to collapse. The collapse finally takes place when the hydrophobic effects overcome electrostatic repulsion. Within the collapsed globule, charge becomes negligible with rampant counterion adsorption that minimizes the electrostatic energy penalty resulting from inter-monomer electrostatic repulsion. In this process, chain shrinkage is induced by both hydrophobicity (aχ) and increasing Coulomb strength (lB, through ε and T). It is to be noted that only aχ is altered (for the mixture of 1-propanol and 2-pentanone containing quarternized poly-2-vinylpyridine) in effecting the coil-globule transition keeping the Coulomb strength fixed in Ref.28. Similar measurements of size and ionic conductivity as the temperature is varied would further validate the major concepts presented in this article. Noteworthy is that this mechanism of collapse due to hydrophobic phase-separation is in contrast with the collapse in good solvents3,4,21 due to counterion correlations. In addition to the system being on the other side of the Flory temperature, the good solvent model21 does not account for counterion adsorption which plays the major role of charge-regularization in our theory.

It is to be noted that our theoretical model does not predict the collapse transition to be continuous with increasing values of N. With fixed N, at decreasing values of the three-body parameter w3 the transition becomes ‘more discontinuous’ in the sense that the jump in l̃1 increases (see both Fig. 2 and 3). One notes that [Eq. 3.2] l̃1 goes as or with . Therefore, with increasing values of N the expansion factor l̃1 becomes progressively smaller, whereas l̃1 for the expanded chain (in the adiabatic limit) becomes progressively larger (verified numerically). Therefore, the jump for l̃1 actually increases with N.

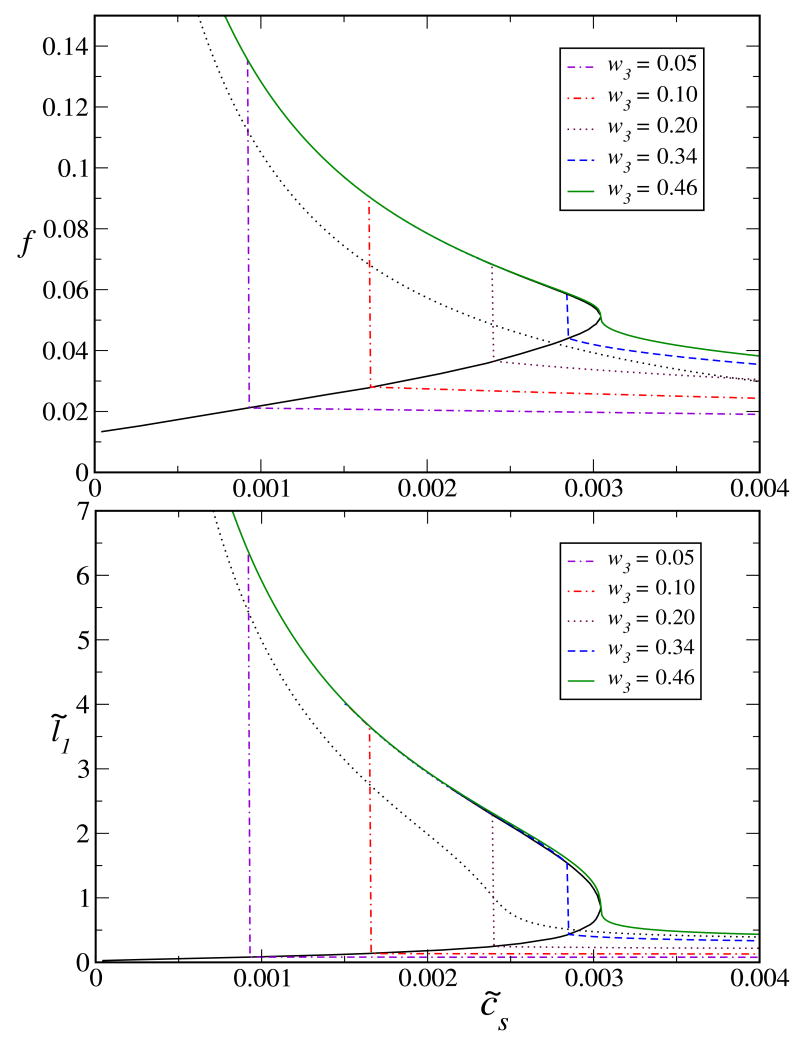

Fig. 3.

Ionic strength (salt) induced collapse of a fully ionizable polyelectrolyte chain. Fixed parameters are: N = 1000, ρ̃ = 0.0005, δ = 3.0, Ionizability fm = 1.0, aχ = 10/9, t = 0.02653, and therefore, l̃B = 3.0, and w = −0.333. Critical values are: , , , and f* = 0.051. For the special case of NaPSS in water, l̃B = 900/T and Θt = 400K. Then T = 300K implying a possible collapse at room temperature. Dotted curves are the analytical result [Eq. (3.1)] in the expanded state.

In Fig. 3 we present the phase boundaries for the ionic strength (salt) induced collapse of a fully ionizable PE at t = 0.02653, at which the solvent is poor (note, aχ = 10/9). This shows that a room temperature collapse of a polymer of type NaPSS in water is possible (for NaPSS in water, at T = 300K, t = 0.02653) in the presence of salt but unlikely at salt-free conditions (Fig. 2) unless solvent poorness is drastically enhanced28 or the dielectric constant is substantially reduced. There are remarkable qualitative similarities between the salt and temperature induced collapse transitions. In the presence of salt, the monomer-monomer repulsion becomes weaker even at the same degree of ionization. In addition, salt induces more counterion adsorption5 which reduces f. Therefore, in the presence of salt, the overall resisting force that prevents the collapse becomes substantially weaker. This phenomenon is manifest in Fig. 3. The critical points obtained are: , , , and f* = 0.051. A higher value of the critical charge compared to the salt-free case (Fig. 1) is not surprising, as with salt the repulsion becomes weaker for the same f.

One finally notes that computer simulations31–39 ignore the dielectric heterogeneity present in real experimental polymeric systems. The equivalent in our theory is choosing a low value of δ for which the counterion adsorption is less than substantial and thus raising the possibility of a necklace-like structure. Experiments28, however, indicate rough spherical objects with substantial incorporation of counterions within them, as predicted by our model. It must be remarked, however, that the theory employed in this work is based on a uniform expansion model, and it is beyond the scope of the current work to address the issue of the surface tension for a counterion adsorption model of necklace structures. The necklace-globule regime exists both in computer simulations and scaling models for a relatively narrow range of parameters. Although it is predictable that the regime will be narrower if one allows the counterions to adsorb (which reduces the overall charge the presence of which creates the necklace in the first place), it remains an open question whether the necklace structure will completely disappear in a theoretical analysis.

B. Approximate formulas

In our efforts to simplify the numerical work and obtain insight into the relative strengths of the various contributing factors, we consider a few analytically tractable limits, namely the expanded chain, the collapsed chain, and the collapse condition.

1. The expanded chains

We first note that f features in F5 only in the fourth term that describes the long-range electrostatic interactions between charged monomers. However, especially in extended chain configurations, the adsorption energy (F4) related to the short-range ion-pair electrostatics is more significant than F5, and shows a greater variation with f in most conditions. In salty solutions for the polyelectrolyte chain, we notice that at low salt both the logarithmic and the linear terms in F2 will dominate the f3/2 term in F3, and at high salt the variation of F3 with f is negligible. A meticulous numerical analysis confirms the validity of the above analysis lending support to ignore the F5 terms in comparison to the first four terms in the free energy in determining f. Thus, we make an adiabatic approximation in which the chain free energy (F5) is decoupled from the rest and Fad = F1 + F2 + F4 are the relevant contributions that determine the effective charge f in the expanded chain. Within this adiabatic approximation, therefore, Fad does not contain the expansion factor and we can minimize over only α to obtain the effective charge. ∂Fad/∂α = 0 gives us, using f = fm − α,

| (3.1) |

(fm = 1 for a fully ionizable chain). This equation is an explicit closed-form analytical expression for the effective charge, as a function of the monomer density, maximum ionizability, salt concentration, the Bjerrum length (temperature and the bulk dielectric constant), and the dielectric mismatch parameter δ. δ = C2εl0 has a non-universal constant C2 = (εld)−1, which can be determined from experiments using Eq. (3.1). Further, the contributions to Fad only depend on the number of ionizable monomers inside a polymeric system, not on the size and shapes of the chains. Consequently, in the first approximation the effective charge depends only on the average monomer density ρ (in volume Ω), but not explicitly on the molecular weight (N). One may note that the product of lB and δ, not their individual values, is the effective Coulomb strength to determine the charge of the chain in the swollen state. The coil size is then determined by minimizing F5 with respect to l̃1, using the f from Eq. (3.1). Comparison with our numerical results shows that this is a good approximation for a wide range of conditions as long as the chain is in the swollen state. The adiabatic approximation, however, progressively fails for lower molecular weights, higher lB's and lower δ's (F5 becomes important and comparable to F4 in those cases). This formula also breaks down when the coil-globule transition is approached, as is evident from Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, where the dotted curves are the analytical results in the expanded state for f and l̃1 from Eq. (3.1).

2. The collapsed chain

When a PE chain collapses (l̃1 ≤ 1, the Gaussian value) in a poor solvent away from the critical point, the chain collects most of its counterions reducing the effective charge and the electrostatic penalty, and the two- and three-body interaction terms (the second and third terms in F5, respectively) become the most important in the overall free energy. In this case, the first four terms (F1 − F4) become independent of f. It has been thoroughly verified numerically that f in the collapsed globule becomes negligible for all practical purposes, especially at salt-free conditions in which the electrostatic repulsion among monomers is very strong. Thus we safely employ the quasi-neutral chain approximation in which we assume f ≃ 0 or α = fm, and only F5 (with the fourth term in it being zero) survives. This approximation breaks down (verified numerically - please see the figures) progressively closer to the critical point where the electrostatic interactions between monomers become comparable to the excluded volume and steric interactions. However, away from the critical point ∂F5/∂l̃1 = 0, in conjunction with l̃1 ≤ 1 in the collapsed state, yield the expansion factor

| (3.2) |

This implies that , or Rg ∼ N1/3, which is the well-known compact globule limit valid for neutral chains. Note that w must be negative to have a collapse (l̃1 ≤ 1). Using this value of , we obtain the free energy of the collapsed globule

| (3.3) |

3. The collapse condition

Now, exactly at collapse the binodal (equal chemical potential) states are, respectively, the f = 0 (collapsed) and f ≠ 0 (expanded). At the collapse transition, these two states must have the same total equilibrium free energy. This condition yields, using Eq. (3.3),

| (3.4) |

or

| (3.5) |

where, αc satisfies Eq. (3.1), and the dependency of w on t is given as w = 1 − aχ/(10πt). Considering the temperature dependency of the Bjerrum length, l̃B = 1/4πt, simultaneous solutions of t and αt from two equations - the inverted form of Eq. (3.1), i.e.,

| (3.6) |

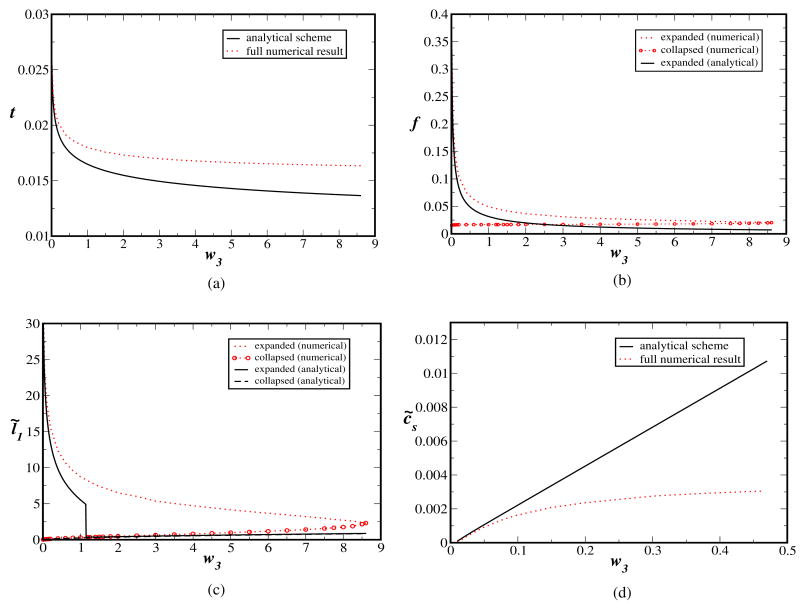

and Eq. (3.5) - give us the temperature and the effective charge of the expanded chain at collapse. A comparison between the approximate results from the above formulas and the numerical results is provided in Figure 3, where the transition temperature tt (Fig. 3a), the degree of ionization at the transition (Fig. 3b), the size of the chain in the expanded and collapsed states at the transition (Fig. 3c) for the temperature induced collapse, and the transition salt concentration c̃s,t for the salt-induced collapse (Fig. 3d) are plotted against the three-body interaction parameter w3. As is evident, the simplified approximation captures only the qualitative trend. Nevertheless, since many experimental variables appear collectively through only one analytical formula for the effective charge, the approximation carried out here might be of use in easily predicting the experimental trends, without having to confront extensive numerical work.

IV. Conclusions

We have used the counterion adsorption theory to describe the collapse of a single, isolated, and flexible polyelectrolyte chain in a poor solvent. Careful numerical analysis suggests that a combination of the entropy of free counterions, adsorption (Coulomb) energy of bound counterion ion-pairs and chain free energy plays the key role to determine the charge and size of the polymer. The local dielectric constant and ionization equilibrium, and their coupling to chain conformations are accounted for. The critical point and the full phase boundary for the first-order coil-globule transition were determined by self-consistent double-minimization of the free energy in terms of the size and charge of the polyelectrolyte chain, both in salt-free and salty solutions. At low Coulomb strengths the chain remains expanded due to its substantial charge, which decreases with increasing Coulomb strength. If the charge is lower than a certain value, collapse occurs leading to a collection of counterions in the compact globule. It has also been observed that a substantially low value of dielectric constant might allow for a collapse transition of the PE chain at room temperature without salt. In the presence of salt, however, collapse can occur in aqueous media (high dielectric constants) at modest temperatures. The occurrence of the coil collapse into a globule is accompanied by a discontinuous reduction in the net charge of the polymer.

As far as experimental verification of these results are concerned, simultaneous measurements of polymer size and ionic conductivity in dilute solutions as the temperature is varied, analogous to those at constant temperature with varying solvent quality, would validate the major concepts presented in this paper. Furthermore, the main ideas of the phase transitions, arising from the coupling between counterions and polymer conformations, presented here are also valid for the volume transitions of polyelectrolyte gels and brushes. New experiments that will monitor the counterion density inside the gels and brushes are expected to stimulate a fundamental understanding of this important class of soft materials. In light of this theory, the previous paradigm where the phase behavior of gels, brushes, and polyelectrolyte solutions has been treated with fixed charges needs to be reworked.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the approximate (and mostly analytical) scheme for the collapse condition with the numerical result. For the Coulomb-strength-induced collapse, the reduced temperature, t (a), degree of ionization, f (b), and effective expansion factor, l̃1 (c), at the transition, are plotted against the three-body interaction parameter w3. For the ionic-strength-induced collapse, the salt concentration, c̃s (d), is plotted against w3. Only the qualitative trends are captured by the approximate formulas. Systematic and substantial deviation from the full numerical result are observed for higher values of w3. Note that the degree of ionization in the collapsed globule is zero (b) in the approximate scheme.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rajeev Kumar for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grant No. 5R01HG002776 and National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant No. 0605833.

References

- 1.Beer M, Schmidt M, Muthukumar M. Macromolecules. 1997;30:8375. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens MJ, Kremer K. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:1669. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkler RG, Gold M, Reineker P. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;80:3731. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Muthukumar M. J Chem Phys. 2002;116:9975. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muthukumar M. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:9343. doi: 10.1063/1.1701839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams C, Brochard F, Frisch HL. Ann Rev Phys Chem. 1981;32:433. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birshtein TM, Pryamitsyn VA. Macromolecules. 1991;24:1554. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lifshitz IM, Grosberg AY, Khokhlov AR. Rev Mod Phys. 1978;50:68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muthukumar M. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:6272. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shew CY, Yoshikawa K. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:144913. doi: 10.1063/1.2714552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha BY, Thirumalai D. Phys Rev A. 1992;46:R3012. doi: 10.1103/physreva.46.r3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dua A, Vilgis TA. Europhys Lett. 2005;71:49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shew CY, Yethiraj A. J Chem Phys. 1999;110:676. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiessel H, Pincus P. Macromolecules. 1998;31:7953. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiessel H. Macromolecules. 1999;32:5673. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka T, Fillmore D, Sun ST, Nishio I, Swislow G, Shah A. Phys Rev Lett. 1980;45:1636. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramarenko EY, Khokhlov AR, Yoshikawa K. Macromol Theory Simul. 2000;9:249. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasilevskaya VV, Khokhlov AR, Yoshikawa K. Macromol Theory Simul. 2000;9:600. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramarenko EY, Erukhimovich IY, Khokhlov AR. Macromol Theory Simul. 2002;11:462. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrynin AV, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 2001;34:1964. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brilliantov NV, Kuznetsov DV, Klein R. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;81:1433. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uyaver S, Seidel C. Macromolecules. 2009;42:1352. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasilevskaya VV, Khokhlov AR, Matsuzawa Y, Yoshikawa K. J Chem Phys. 1995;102:6595. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda M, Yoshikawa K. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:2133. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshikawa K, Takahashi M, Vasilevskaya VV, Khokhlov AR. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;76:3029. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada A, Kubo K, Nakai T, Yoshikawa K. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;86:223901. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, Zhao J. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:091104. doi: 10.1063/1.2711804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh P, Deen GR, Vollmer D, Fischer K, Schmidt M, Kundagrami A, Muthukumar M. Macromolecules. 2008;41:9352. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang R, Yethiraj A. Macromolecules. 2006;39:821. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy G, Yethiraj A. Macromolecules. 2006;39:8536. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobrynin AV, Rubinstein M, Obukhov SP. Macromolecules. 1996;29:2974. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyulin AV, Dunweg B, Borisov OV, Darinskii AA. Macromolecules. 1999;32:3264. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Micka U, Kremer K. Europhys Lett. 2000;49:189. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limbach HJ, Holm C, Kremer K. Europhys Lett. 2002;60:566. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiriy A, Gorodyska G, Minko S, Jaeger W, Stepanek P, Stamm M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13454. doi: 10.1021/ja0261168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirwan LJ, Papastavrou G, Borkovec M. Nano Lett. 2004;4:149. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limbach HJ, Holm C. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:8041. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limbach HJ, Holm C, Kremer K. Macromol Symp. 2004;211:43. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeon J, Dobrynin AV. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7695. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthukumar M. J Chem Phys. 1987;86:7230. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raphael E, Joanny JF. Europhys Lett. 1990;13:623. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning GS. J Chem Phys. 1969;51:924. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manning GS. Macromolecules. 2007;40:8071. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehler EL, Eichele G. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3887. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamm G, Pack GR. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:959. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gong H, Hocky GM, Freed KF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804506105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muthukumar M. Macromolecules. 2002;35:9142. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka T. Phys Rev Lett. 1978;40:820. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grosberg AY, Khokhlov AR. Statistical Physics of Macromolecules. AIP Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]