Abstract

Substance P (SP) is a neuropeptide with neuroimmunoregulatory activity that may play a role in susceptibility to infection. Human mast cells, which are important in innate immune responses, were analysed for their responses to pathogen-associated molecules via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in the presence of SP. Human cultured mast cells (LAD2) were activated by SP and TLR ligands including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Pam3CysSerLys4 (Pam3CSK4) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), and mast cell leukotriene and chemokine production was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and gene expression by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Mast cell degranulation was determined using a β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) assay. SP treatment of LAD2 up-regulated mRNA for TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 and TLR9 while anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) stimulation up-regulated expression of TLR4 only. Flow cytometry and western blot confirmed up-regulation of TLR2 and TLR8. Pretreatment of LAD2 with SP followed by stimulation with Pam3CSK4 or LTA increased production of leukotriene C4 (LTC4) and interleukin (IL)-8 compared with treatment with Pam3CSK4 or LTA alone (> 2-fold; P < 0·01). SP alone activated 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) nuclear translocation but also augmented Pam3CSK4 and LTA-mediated 5-LO translocation. Pam3CSK4, LPS and LTA did not induce LAD2 degranulation. SP primed LTA and Pam3CSK4-mediated activation of JNK, p38 and extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and activated the nuclear translocation of c-Jun, nuclear factor (NF)-κB, activating transcription factor 2 (ATF-2) and cyclic-AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) transcription factors. Pretreatment with SP followed by LTA stimulation synergistically induced production of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL8)/IL-8, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)/monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 protein. SP primes TLR2-mediated activation of human mast cells by up-regulating TLR expression and potentiating signalling pathways associated with TLR. These results suggest that neuronal responses may influence innate host defence responses.

Keywords: chemokines, immunoglobulin E, mast cells, neuropeptides, substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide

Introduction

Substance P (SP) is a neuropeptide that belongs to the tachykinin family of peptides and is implicated in neurogenic inflammation. Although SP is a peptide of neuronal origin it is also found in non-neural cells including endothelial cells,1 macrophages,2 granulocytes, lymphocytes3 and dendritic cells.4 It stimulates immune cells to produce inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interferon (IFN)-γ, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1β. SP induces chemotaxis and degranulation of neutrophils and stimulates respiratory burst.5 In addition, SP promotes vasodilatation and increases vasopermeability, thus ensuing extravasation and accumulation of leucocytes at sites of injury.6

Most importantly, SP promotes innate immune responses and is necessary for successful resolution of bacterial infections. Blocking the action of SP in mice increases their susceptibility to Salmonella infections7 and to Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection.8 Bacterial infections up-regulate the expression of the SP receptor, neurokinin receptor 1 (NKR1), by macrophages, suggesting that SP may be involved in early, innate immune responses.7,9 Furthermore, the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum encodes a peptidase that can cleave SP,10 suggesting that SP may be a target for evading the host immune system.

In addition to its immunomodulatory activity, SP has antibacterial activity11 and has similarities to the innate immune antibacterial defensins.12–14 This suggests possible co-regulation of neuropeptide and innate immune mediators, particularly in bacterial and viral infections. In a recent study of 69 children, it was found that SP and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) mRNA expression was reduced in children with bacterial colonization, and TLR3 (and possibly TLR2) mRNA expression was increased in children with rhinovirus infection.15 Therefore, there is evidence that SP and TLR gene expression in airway cells is co-regulated and that reduced expression of SP may be associated with impaired bacterial clearance.

Mast cells are the major cells involved in allergic inflammation and facilitate innate immune responses in the skin, gut and lung. In some cases, mast cells are activated when immunoglobulin E (IgE) molecules bound to the Fc epsilon receptor I (FcεRI) on the mast cell surface are cross-linked by specific antigen, triggering mast cell degranulation and de novo synthesis of arachidonic metabolites, cytokines and chemokines. However, mast cells express NKR1 receptors and are activated by SP16 to release relatively large quantities of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [MCP-1/chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)].16 SP activation of human mast cells is distinct from that of FcεRI ligation and the mediators released by these two stimuli are likewise distinct. In this study, we hypothesized that SP modulates the expression of TLR on human mast cells and that changes in TLR expression modify human mast cell responses to TLR ligands.

Materials and methods

Human mast cell culture

LAD217 mast cells (a kind gift from Drs. A. Kirshenbaum and D. D. Metcalfe, Laboratory of Allergic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD, USA) were cultured in serum-free media (StemPro-34 SFM; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF). The cell suspensions were maintained at a density of 105 cells/ml at 37° and 5% CO2.

Degranulation assay

LAD2 cells were untreated or treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr, and then activated with Pam3CysSerLys4 (Pam3CSK4; 1, 10 and 100 μg/ml), lipoteichoic acid (LTA; 1, 10 and 100 μg/ml), lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1, 10 and 100 ng/ml), and compound 48/80 (c48/80; 0·25, 0·5 and 1 μg/ml) and incubated at 37° for 0·5 hr. The β-hexosaminidase released into the supernatants and in cell lysates was quantified by hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamide (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 0·1 m sodium citrate buffer (pH 4·5) for 90 min at 37°. The percentage of β-hexosaminidase release was calculated as a percentage of the total content. SP-treated LAD2 cells were also activated with A23187 (1 μm) for 30 min and β-hexosaminidase release was measured.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from each preparation using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Five micrograms of total cellular RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Taqman Reverse Transcription reagents and Random Hexamer primer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Gene expression was analysed using real-time PCR on an ABI7500 SDS system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsdad, CA). Fifty nanograms of cDNA was used in each quantitative PCR assay. Primer sets for PCR amplifications were designed using the Primer Express software (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). All reactions were performed in triplicate for 40 cycles as per the manufacturer's recommendation. Samples were normalized using the geometric mean of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)18 and data are reported as the ratio of treated cells to untreated control cells.

Flow cytometric analysis

LAD2 cells were untreated or treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr. Cells were washed and resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with anti-TLR antibodies (Table 1) or appropriate isotype control antibody (Table 1) for 30 min at 4°. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS/0·1% BSA and analysed on a FACSArray or FACSAria (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON). Data were further analysed using Flowjo 7.2.2 software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Table 1.

Antibodies used in flow cytometry and western blot analysis

| Specificity | Conjugation | Supplier | Immunoglobulin species | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | APC | eBioscience | ms | Flow cytometry |

| TLR2 (1F10) | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | ms | Western blot |

| TLR4 | PE | eBioscience | ms | Flow cytometry |

| TLR4 (H-80) | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | rb | Western blot |

| TLR8 | Alexa Fluor® 647 | IMGENEX | rt | Flow cytometry |

| TLR8 (D-14) | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | gt | Western blot |

| TLR9 | FITC | eBioscience | rt | Flow cytometry |

| TLR9 (4H286) | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | ms | Western blot |

| Actin | Unconjugated | Sigma-Aldrich | rb | Western blot |

| Anti-pJNK | Unconjugated | Cell Signaling | rb | Western blot |

| Anti-pp38 | Unconjugated | Cell Signaling | rb | Western blot |

| Anti-pERK | Unconjugated | Cell Signaling | rb | Western blot |

| Anti-ERK (C-16) | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | rb | Western blot |

| Anti-mouse | Horseradish peroxidase | Santa Cruz | gt | Western blot |

| Anti-rabbit HRP | Horseradish peroxidase | Invitrogen | gt | Western blot |

| Anti-goat HRP | Horseradish peroxidase | Sigma-Aldrich | rb | Western blot |

| Mouse isotype control | APC | BD Biosciences | ms | Flow cytometry |

| Mouse isotype control | PE | BD Biosciences | ms | Flow cytometry |

| Rat isotype control | Alexa Fluor® 647 | IMGENEX | ms | Flow cytometry |

| Rat isotype control | FITC | BD Biosciences | rt | Flow cytometry |

| Goat anti-5-LO | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz | gt | Confocal microscopy |

| Anti-goat | AlexaFluor 488 | Invitrogen | rb | Confocal microscopy |

5-LO, 5-lipoxygenase; APC, allophycocyanin; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; PE, phycoerythrin; pERK, phosphorylated extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; pJNK, phosphorylated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; pp38, phosphorylated p38; TLR, Toll-like receptor, ms, mouse; rb, rabbit; gt, goat.

Western blot

LAD2 cells were washed with PBS and 1 × 106 cells were lysed in buffer containing loading dye solution [lithium dodecyl sulphate (LDS)] sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10%β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 0·1 m dithiothreitol (DTT; Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Whole-cell lysates (30 μg) were separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 3% milk in Tris buffered saline (TBS)-0·05% Tween for 1 hr and then probed with primary antibodies against TLR (Table 1), phospho-stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (SAPK)/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) (Thr183/Tyr185; Cell Signaling Technology; Danvers, MA), phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182; Cell Signaling Technology) and phospho-extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling Technology), or anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) in 4% BSA/PBS for 1 hr at room temperature. The membranes were washed with TBS-Tween 3X and then incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Table 1) for 1 hr. The nitrocellulose membranes were developed with chemiluminescence reagent (Invitrogen) for 1 min and exposed to high-performance chemiluminescence film for 1–5 min.

DNA-binding activity of nuclear transcription factor proteins

Nuclear protein was extracted from SP-treated LAD2 cells 30 min after Pam3CSK4 or LTA activation using a nuclear extract kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), according to the supplier's instructions. The nuclear extracts (10 μg of protein/aliquot) were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (TransAM kits; Active Motif) for DNA-binding activity of phospho-c-Jun, activating transcription factor 2 (ATF-2), cyclic-AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) and nuclear factor (NF)-κB p50. The transcription factor proteins, bound to immobilized oligonucleotides corresponding to appropriate consensus gene response elements, were detected with specific antibodies (Abs), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin, according to the supplier's instructions. DNA-binding activity is expressed as a ratio to the positive control (untreated cell extract).

Cytokine ELISAs

LAD2 cells were washed with medium and suspended at 0·2 × 106 cells per well, preincubated with SP (100 nm; Sigma-Aldrich) or untreated, and stimulated with LTA (Sigma-Aldrich), Pam3CSK4 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA), or LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 hr. Cell-free supernatants were then analysed for CysLT release by ELISA (Cayman chemical company; Ann Arbor, MI). In other experiments, LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with LTA (10 μg/ml) for 16 hr, and IL-8 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), TNF (R&D Systems), MCP-1 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and IL-6 (eBioscience) production was measured by ELISA purchased commercially as indicated.

Confocal microscopy

LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and stimulated with Pam3CSK4 (10 μg/ml) or LTA (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37° and 5% CO2. Cells were washed with PBS and cytospin slides were prepared. Slides were fixed in 0·5% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7·4) at 4° for 30 min, rinsed with PBS, and permeabilized with 0·1% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4° for 30 min. The slides were then washed once with PBS and incubated for 1 hr with 0·1% BSA in PBS at 4° for 1 hr. They were then washed twice with cold PBS and incubated with anti-5-lipooxygenase (5-LO; 2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) or with vehicle control (PBS) for 20 hr at 4°. Slides were incubated with TO-PRO-3 (Invitrogen; 1 μm) or AlexaFluor-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen; 20 μg/ml) at 4° for 1 hr, washed with cold PBS, air-dried and mounted using FluorSave reagent (Sigma; Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Slides were examined using a ×100 objective under a Zeiss 510 Meta laser-scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least five separate times (unless otherwise stated) and in quadruplicate and values displayed represent mean ± standard error of the mean. P-values were determined using Student's t-test (when comparing two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (when comparing more than two groups).

Results

SP up-regulates expression of TLRs

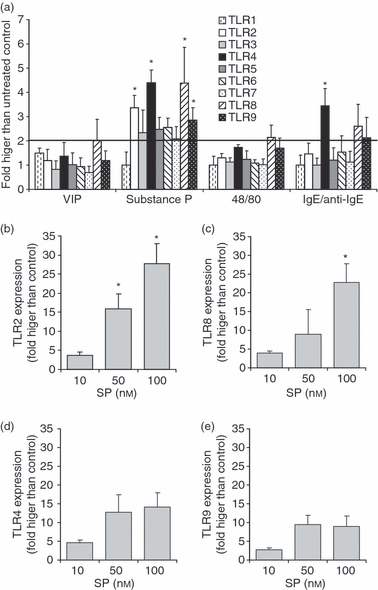

We have previously shown that human mast cells express several TLRs19 and that neuropeptides, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and SP activate LAD2 human mast cells16 to produce chemokines and cytokines by activating gene transcription. We hypothesized that these signalling pathways may likewise alter expression of surface receptors such as TLR. To determine the effects of neuropeptides on TLR expression, LAD2 cells were treated with VIP, SP, compound 48/80 and IgE/anti-IgE for 3 hr and TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1a). SP significantly up-regulated expression of TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 and TLR9 (3·4-, 4·4-, 4·4- and 2·9-fold compared with untreated, respectively; P < 0·01) while IgE/anti-IgE stimulation up-regulated expression of TLR4 only (3·4-fold compared with untreated; P < 0·01). VIP and compound 48/80 did not significantly up-regulate expression of any of the TLRs tested. SP concentration-dependently increased TLR2 (Fig. 1b) and TLR8 (Fig. 1c) expression. SP induction of TLR4 and TLR9 expression was not similarly concentration-dependent and SP at concentrations higher than 50 nm did not significantly increase TLR4 or TLR9 expression when compared with 10 nm SP.

Figure 1.

Substance P (SP) up-regulated Toll-like receptor (TLR) mRNA expression. (a) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (10 nm) for 3 hr and TLR expression was analysed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). LAD2 cells were treated with 10, 50 and 100 nm SP for 3 hr and TLR2 (b), TLR8 (c), TLR4 (d) and TLR9 (e) expression was analysed by qPCR. All data represent five experiments and asterisks represent P < 0·01 compared with the untreated control. IgE, immunoglobulin E; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide.

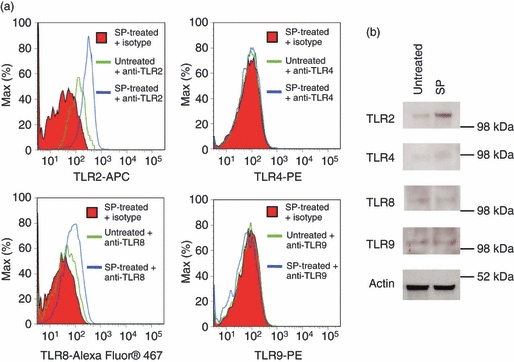

To determine the effect of SP on TLR protein expression, LAD cells were treated with SP for 24 hr and TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 and TLR9 expression was determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 2a) and western blot analysis (Fig. 2b). Conventional flow cytometry analysis of unpermeabilized cells showed no detectable expression of TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 or TLR9 (data not shown). As a result, LAD2 cells were fixed and permeabilized and intracellular flow cytometric analysis was performed as described in the Materials and methods. Intracellular flow cytometry showed that LAD2 cells constitutively expressed TLR2 and TLR8 but not TLR4 or TLR9 (Fig. 2a). SP up-regulated expression of TLR2 by approximately 50% and TLR8 by 20% compared with untreated cells. Western blot analysis confirmed that LAD2 cells expressed TLR2 and TLR8 constitutively (Fig. 2b). However, when membranes were blotted using antibodies specific for TLR4 and TLR9, faint bands were detected at > 98 and < 98 kDa, respectively, indicating that these proteins may also be expressed constitutively. SP up-regulated expression of TLR2 but there was no significant change in expression of TLR4, TLR8 or TLR9 as measured by western blot analysis.

Figure 2.

Substance P (SP) up-regulated Toll-like receptor (TLR) protein expression. (a) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and TLR expression was analysed by flow cytometry. (b) LAD2 cells were treated with 100 nm SP for 24 hr and TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 and TLR9 expression was analysed by western blot. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

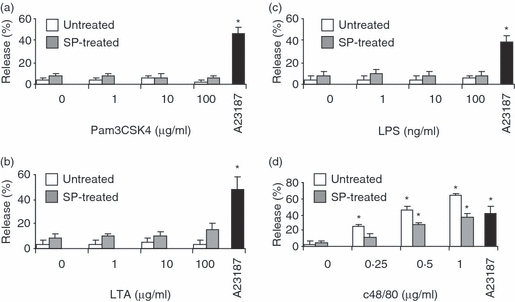

TLR ligands do not activate mast cell degranulation even after SP treatment

It has been shown that, in certain situations, TLR ligands can activate mast cell degranulation20 and that TLR and FcεRI mediate synergistic signals that can augment mast cell activation.21 Therefore, the effect of SP and TLR2 ligands (Pam3CSK4 and LTA) on LAD2 degranulation was determined by measuring the release of the granule marker β-hexosaminidase. LPS, a TLR4 ligand, was used as a negative control as qPCR and western blot analysis showed no effect of SP on TLR4 expression (Fig. 2). On their own, Pam3CSK4, LPS and LTA did not activate LAD2 degranulation even after pretreatment with SP for 24 hr (Fig. 3a–c). SP-treated LAD2 cells degranulated in response to calcium ionophore (A23187), showing that the cells still possessed intact granules and could release them upon mobilization of intracellular calcium. Furthermore, untreated and SP-treated cells could also degranulate in response to compound 48/80, a general G protein activator, suggesting that the signalling processes required for degranulation in response to G protein-coupled stimuli were intact in SP-treated cells. Interestingly, SP-treated LAD2 cells degranulated approximately 20–30% less than the untreated control (Fig. 3d). SP degranulates mast cells16, thus depleting their granule contents. In Fig. 3d, the subsequent activation with compound 48/80 and A23187 was performed 24 hr after SP treatment, and this is probably not enough time for the slow-growing LAD2 cells to replenish their granule stores.

Figure 3.

Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands did not active mast cell degranulation even after substance P (SP) treatment. LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with Pam3CysSerLys4 (Pam3CSK4) (a), lipoteichoic acid (LTA) (b), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (c) and compound 48/80 (c48/80; d) for 30 min, and β-hexosaminidase release was measured as described in the Materials and methods. As a positive control, SP-treated LAD2 cells were also activated with A23187 (1 μm) for 30 min and β-hexosaminidase release was measured. All data represent five experiments and asterisks represent P < 0·01 compared with the untreated and unstimulated control.

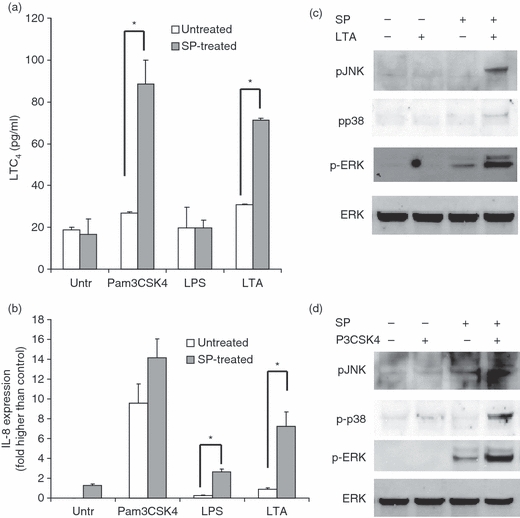

SP primes Pam3CSK4- and LTA-induced production of LTC4 and IL-8

Human mast cells produce arachidonic metabolites such as leukotrienes in response to TLR2 but not TLR4 activation.20 To determine whether SP-mediated induction of TLR2 expression resulted in modulation of TLR-mediated activation of arachidonic acid metabolism, LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP for 24 hr, washed with fresh medium and stimulated with Pam3CSK4, LTA and LPS for 4 hr, and CysLT release was then measured. Pretreatment of LAD2 cells with SP followed by stimulation with Pam3CSK4 or LTA potentiated production of LTC4 compared with treatment with Pam3CSK4 or LTA alone (2·6- and 2·1-fold over control, respectively; P < 0·01; Fig. 4a). To determine whether TLR-induced IL-8 expression was also modulated by SP treatment, LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP for 24 hr and activated with Pam3CSK4, LPS and LTA for 3 hr, and IL-8 genes expression was then analysed by qPCR (Fig. 4b). Pam3CSK4 alone stimulated significant expression of IL-8 (P < 0·01 when compared with untreated and unstimulated control; Fig. 4b) and SP treatment did not significantly augment its production. LPS and LTA on their own did not induce significant expression of IL-8 but SP treatment significantly augmented expression compared with the untreated control (3·8 and 6·7-fold, respectively; P < 0·01; Fig. 4b). As IL-8 production is the result of MAPK activation, phosphorylation of the major MAPKs, namely c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 and ERK, was measured by western blotting (Fig. 4c,d). On its own, LTA treatment did not stimulate JNK, p38 or ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4c). SP alone stimulated ERK but not JNK or p38 phosphorylation. Together, SP and LTA stimulated JNK, p38 and ERK phosphorylation in a synergistic manner. On its own, Pam3CSK4 did not stimulate p38, ERK or JNK phosphorylation but cells stimulated with Pam3CSK4 and SP together showed phosphorylation of JNK, p38 and ERK.

Figure 4.

Substance P (SP) primed lipoteichoic acid (LTA)- and Pam3CysSerLys4 (Pam3CSK4)-mediated activation of human mast cells. (a) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with Pam3CSK4 (10 μg/ml), LTA (10 μg/ml) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/ml) for 4 hr, and CysLT release was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). (b) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with Pam3CSK4 (10 μg/ml), LTA (100 mg/ml) and LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 hr, and interleukin (IL)-8 production was measured by ELISA. Data in (a) and (b) represent five experiments and asterisks represent P < 0·01 compared with the untreated control (‘Untr’). (c) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) and/or LTA (10 μg/ml) for 30 min and protein lysates were analysed for phospho-c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (pJNK), phospho-p38 (pp38), phospho-extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (pERK) and total ERK expression by western blot. (d) LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) and/or Pam3CSK4 (P3CSK; 10 μg/ml) for 30 min and protein lysates were analysed for phospho-JNK, phospho-p38, phospho-ERK and total ERK expression by western blot. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

SP primes LTA-mediated activation of transcription factors

The activation of JNK, p38 and ERK phosphorylation results in the activation of several transcription factors and initiates their translocation to the nucleus, where they facilitate transcription of genes such as IL-8. SP activation of G protein-coupled signalling results in NF-κB16 and cyclic-AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB)22 phosphorylation and translocation to the nucleus, while TLR2 ligation activates activating transcription factor 2 (ATF-223) and c-Jun transcription factors, among others. Activation of c-Jun, ATF-2, NF-κB and CREB in nuclear extracts of SP- and LTA-treated cells was performed using an oligonucleotide binding assay (Fig. 5). SP stimulated the activation and translocation of NF-κB and CREB (8·17 ± 0·48- and 2·27 ± 0·50-fold higher than in the untreated control, respectively) and LTA alone activated ATF-2 (2·08 ± 0·47-fold higher than in the untreated control). Together, SP and LTA synergistically activated all four transcription factors tested.

Figure 5.

Substance P (SP) primed lipoteichoic acid (LTA)-mediated activation of transcription factors. LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with LTA (10 μg/ml) for 1 hr, and c-Jun (a), activating transcription factor 2 (ATF-2) (b), nuclear factor (NF)-kB (c) and cyclic-AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) (d) activation in nuclear extracts was measured by TransAM binding assays as described in the Materials and methods. Data represent five experiments and asterisks represent P < 0·01 compared with the unstimulated control.

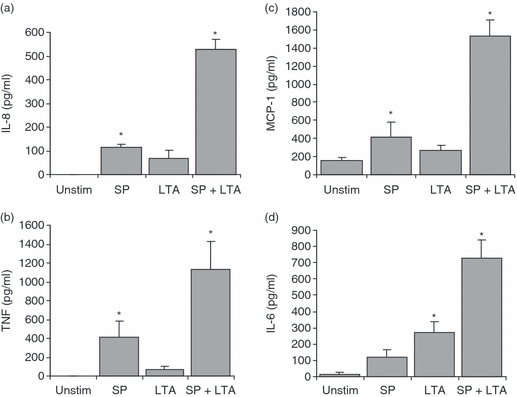

SP primes LTA-mediated production of cytokines and chemokines

To determine the effect of SP on LTA-activated production of cytokines and chemokines, LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP for 24 hr and then activated with LTA and production of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8 (CXCL8)/IL-8, TNF, CCL2/MCP-1 and IL-6 was measured by ELISA (Fig. 6). SP stimulated significant (compared with unstimulated cells) production of IL-8, TNF and MCP-1 but not IL-6, while LTA stimulated significant production of IL-6 only. SP pretreatment significantly (compared with LTA alone) potentiated LTA-induced production of IL-8, TNF, MCP-1 and IL-6 by at least 2-fold.

Figure 6.

Substance P (SP) primed lipoteichoic acid (LTA)-mediated production of cytokines and chemokines. LAD2 cells were treated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with LTA (10 μg/ml) for 16 hr, and interleukin (IL)-8 (a), tumour necrosis factor (TNF) (b), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) (c) and IL-6 (d) production was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data represent five experiments and asterisks represent P < 0·01 compared with the unstimulated control (‘Unstim’).

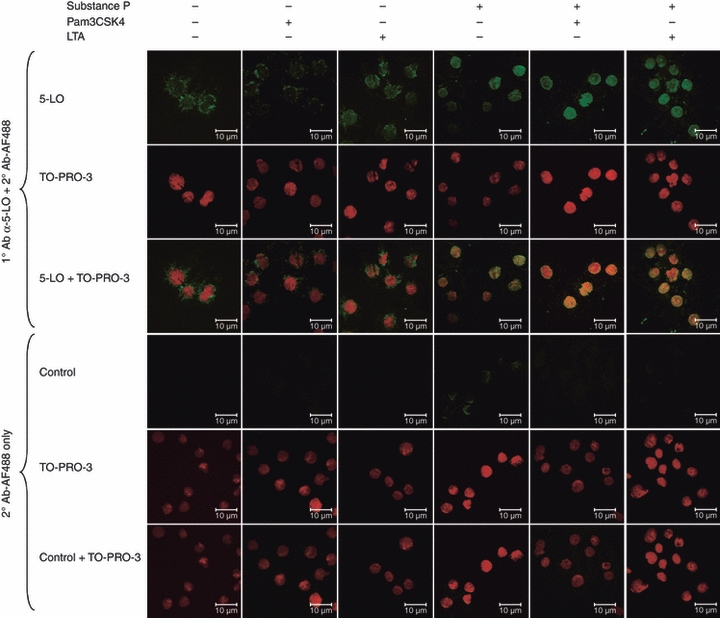

SP primes LTA- and Pam3CSK4-mediated translocation of 5-LO

As SP potentiated LTA- and Pam3CSK4-mediated production of LTC4 (Fig. 4a), we hypothesized that SP mediated this effect at least in part by potentiating the translocation of 5-LO, a key enzyme in the production of CysLTs. LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP and stimulated with either LTA or Pam3CSK4, and 5-LO translocation was then analysed by staining with an anti-5-LO antibody and confocal microscopy (Fig. 7). Nuclei were visualized using TO-PRO-3, a DNA-specific stain. In unstimulated cells, 5-LO localized to the perinuclear region with some cytoplasmic staining. Pam3CSK4 alone did not induce 5-LO translocation. However, both SP and LTA alone induced 5-LO translocation to the nucleus. Confocal images indicate that SP is more effective than LTA at inducing 5-LO translocation. Most importantly, SP potentiated Pam3CSK4- and LTA-induced translocation of 5-LO, confirming the LTC4 data presented in Fig. 4a.

Figure 7.

Substance P (SP) primed lipoteichoic acid (LTA)- and Pam3CysSerLys4 (Pam3CSK4)-mediated translocation of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO). LAD2 cells were pretreated with SP (100 nm) for 24 hr and then activated with LTA (10 μg/ml) or Pam3CSK4 (10 μg/ml) for 30 min and stained with anti-5-LO and TO-PRO-3 (nuclear stain) to determine translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

SP is not only a potent neuropeptide involved in neurogenic signalling mechanisms but is also an immunomodulatory peptide capable of activating transcription factors and altering the expression of immune receptors. In this report, we show that SP modulates the expression of several TLRs and that SP primes LTA- and Pam3CSK4-mediated activation of human mast cells by up-regulating TLR2. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show a direct effect of SP on the expression of specific innate immune receptors.

In this study, SP up-regulated expression of TLR2, TLR4, TLR8 and TLR9 mRNA, as detected by qPCR, and TLR2 protein expression, as detected by flow cytometry and western blot. TLR expression can be modified by infection,24 TLR ligands,25 and localized inflammation,26 although the effect of neuronal activation and neuropeptides on TLR expression is poorly understood. There is some evidence, however, that changes in TLR2 expression occur in the brains of Alzheimer's patients and that proper regulation of TLR2 expression may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease.27 SP is a tachykinin and preferentially binds NKR128. Rodent studies have shown that macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and dendritic cells may also produce SP,4,29,30 although mast cells do not themselves produce SP (B. P.Tancowny and M.Kulka). In the periphery, SP is localized to the primary sensory neurons and neurons intrinsic to the gastrointestinal, respiratory and genitourinary tracts.31 As mast cells are positioned close to peripheral nerves in the skin, they are likely to be exposed to high concentrations of neuropeptides.16 During an infection in the skin or gastrointestinal tract, peripheral nerves could stimulate resident mast cells and cross-talk between these two cell types could influence the progress of that infection. Therefore, understanding the effect of neuropeptides such as SP on mast cell function is of interest.

Increased expression of TLR2 did not prime human mast cells to degranulate in response to LTA or Pam3CSK4, supporting previous findings that these TLR ligands do not cause mast cell degranulation.19,32 This suggests that TLR activation does not involve the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) signalling pathway that ultimately leads to degranulation and that SP does not prime its activation. However, our study shows that SP primes the MAPK pathway by synergistically activating phosphorylation of ERK, p38 and JNK. Although it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how the SP G protein-dependent pathway and TLR2 pathways are interlinked, it is possible that concomitant SP and TLR stimulation activates the MAPK pathway via activation of mitogen-activated extracellular kinase (MEKs), mitogen-activated kinase kinases (MKKs) or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and may also involve upstream regulators such as phospholipase-gamma (PLCγ).

Changes in TLR2 expression had functional significance, as SP pretreatment potentiated Pam3CSK4- and LTA-induced production of IL-8, IL-6, MCP-1/CCL2 and TNF. These pro-inflammatory mediators activate several protective innate immune responses, including recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes and activation of the adaptive immune response.33 Increases in cytokine and chemokine production could be attributed to the synergistic activation of JNK, p38 and ERK phosphorylation. Furthermore, SP primed LTA-mediated activation of transcription factors c-Jun, NF-κB, ATF-2 and CREB. This suggests that a complete immune response to a bacterial infection of the skin, where activation of both peripheral nerve cells and mast cells is likely to occur, involves the production of SP and amplification of TLR activation.

In cases where either SP or TLR2 signalling is not present, bacterial infections are not properly controlled and result in increased mortality rates in rodent model systems. In a mouse model of neurocysticercosis, caused by the cestode Taenia solium, the absence of SP/NKR1 receptor signalling causes an inhibited cytokine response in the granulomas associated with the infection,34 suggesting that SP is essential for the induction of cytokine production in this type of infection. In an ex vivo model of Crytosporidium parvum infection of intestinal tissues, C. parva-infected tissues and tissues from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques with naturally occurring cryptosporidiosis demonstrated elevated SP protein levels compared with tissues from SIV-infected animals without ex vivo C. parvum infection or tissues from SIV-infected animals that had no evidence of cryptosporidiosis,34 suggesting that SP is involved in the inflammatory innate immune response associated with this pathology. NKR1 knock-out mice infected with neurotropic herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) had significantly enhanced levels of HSV-2 in the genital tract and central nervous system following infection compared with wild-type controls.35 NKR1 animals also showed a significantly accelerated disease progression, suggesting that SP signalling contributes to the effectiveness of the antiviral innate immune response.

Our data further show that SP pretreatment potentiated Pam3CSK4- and LTA-induced translocation of 5-LO and activated production of LTC4, an important pro-inflammatory mediator. This is particularly surprising given that, individually, Pam3CSK4 and LTA were poor activators of LTC4 production (Fig. 4a) and Pam3CSK4 was unable to induce 5-LO translocation. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that SP can directly activate the translocation of 5-LO, that TLR ligands alone can translocate 5-LO and that these two pathways can act in synergy to amplify inflammatory responses. These observations may explain some of the neurogenic inflammatory responses that have been observed in previous animal models. For example, in guinea pig models of SP-induced skin inflammatory responses, it has been shown that SP-induced inflammation and oedema may be mediated via NK1 receptor-dependent and independent pathways. Oedema formation induced by lower doses (1 nm and below) of SP was mediated via the direct activation of NK1 receptors, but at higher doses (10 nm and above) oedema formation and leucocyte accumulation appeared to be mediated via the release of mast cell-derived mediators, with 5-LO products playing an important role in leucocyte infiltration36. During an infection, where TLR2 ligands such as Pam3CSK4 and LTA are present, these effects would be amplified.

In the skin, SP contributes to priming of the immune system such that bacterial infections are effectively cleared.37 Our study shows that SP up-regulates TLR, augments LTA- and Pam3CSK4-mediated activation of human mast cells and increases production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-8, MCP-1/CCL2, TNF and IL-6. Therefore, SP-mediated up-regulation of TLR2 may provide a mechanism by which SP amplifies innate immune responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Barb Mitchell for her administrative assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by an interest section grant from the American Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- FcεRI

Fc epsilon receptor 1

- LAD

laboratory of allergic diseases cells

- SP

substance P

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Milner P, Ralevic V, Hopwood AM, Feher E, Lincoln J, Kirkpatrick KA, Burnstock G. Ultrastructural localisation of substance P and choline acetyltransferase in endothelial cells of rat coronary artery and release of substance P and acetylcholine during hypoxia. Experientia. 1989;45:121–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01954843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho WZ, Lai JP, Zhu XH, Uvaydova M, Douglas SD. Human monocytes and macrophages express substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor. J Immunol. 1997;159:5654–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai JP, Douglas SD, Rappaport E, Wu JM, Ho W. Identification of a delta isoform of preprotachykinin mRNA in human mononuclear phagocytes and lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;91:121–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambrecht BN, Germonpre PR, Everaert EG, et al. Endogenously produced substance P contributes to lymphocyte proliferation induced by dendritic cells and direct TCR ligation. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3815–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3815::AID-IMMU3815>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterner-Kock A, Braun RK, van der Vliet A, Schrenzel MD, McDonald RJ, Kabbur MB, Vulliet PR, Hyde DM. Substance P primes the formation of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:834–40. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.6.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tominaga K, Honda K, Akahoshi A, Makino Y, Kawarabayashi T, Takano Y, Kamiya H. Substance P causes adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells via protein kinase C. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:1242–5. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kincy-Cain T, Bost KL. Increased susceptibility of mice to Salmonella infection following in vivo treatment with the substance P antagonist, spantide II. J Immunol. 1996;157:255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lighvani S, Huang X, Trivedi PP, Swanborg RH, Hazlett LD. Substance P regulates natural killer cell interferon-gamma production and resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1567–75. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kincy-Cain T, Bost KL. Substance P-induced IL-12 production by murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;158:2334–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper KG, Zarnowski R, Woods JP. Histoplasma capsulatum encodes a dipeptidyl peptidase active against the mammalian immunoregulatory peptide, substance P. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen CJ, Burnell KK, Brogden KA. Antimicrobial activity of substance P and neuropeptide Y against laboratory strains of bacteria and oral microorganisms. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;177:215–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tossi A. Host defense peptides: roles and applications. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6:1–3. doi: 10.2174/1389203053027539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–95. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grissell TV, Chang AB, Gibson PG. Reduced toll-like receptor 4 and substance P gene expression is associated with airway bacterial colonization in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:380–5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123:398–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirshenbaum AS, Akin C, Wu Y, Rottem M, Goff JP, Beaven MA, Rao VK, Metcalfe DD. Characterization of novel stem cell factor responsive human mast cell lines LAD 1 and 2 established from a patient with mast cell sarcoma/leukemia; activation following aggregation of FcepsilonRI or FcgammaRI. Leuk Res. 2003;27:677–82. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. RESEARCH0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulka M, Metcalfe DD. TLR3 activation inhibits human mast cell attachment to fibronectin and vitronectin. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1579–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCurdy JD, Olynych TJ, Maher LH, Marshall JS. Cutting edge: distinct toll-like receptor 2 activators selectively induce different classes of mediator production from human mast cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:1625–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiao H, Andrade MV, Lisboa FA, Morgan K, Beaven MA. FcepsilonR1 and toll-like receptors mediate synergistic signals to markedly augment production of inflammatory cytokines in murine mast cells. Blood. 2006;107:610–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoniger S, Maronde E, Kopp MD, Korf HW, Nurnberger F. Transcription factor CREB and its stimulus-dependent phosphorylation in cell and explant cultures of the bovine subcommissural organ. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;308:131–42. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Garcia CA, Rehani K, Cekic C, Alard P, Kinane DF, Mitchell T, Martin M. IFN-beta production by TLR4-stimulated innate immune cells is negatively regulated by GSK3-beta. J Immunol. 2008;181:6797–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaaf B, Luitjens K, Goldmann T, van Bremen T, Sayk F, Dodt C, Dalhoff K, Droemann D. Mortality in human sepsis is associated with downregulation of Toll-like receptor 2 and CD14 expression on blood monocytes. Diagn Pathol. 2009;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melkamu T, Squillace D, Kita H, O’Grady SM. Regulation of TLR2 expression and function in human airway epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 2009;229:101–13. doi: 10.1007/s00232-009-9175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leemans JC, Butter LM, Pulskens WP, Teske GJ, Claessen N, van der Poll T, Florquin S. The role of Toll-like receptor 2 in inflammation and fibrosis during progressive renal injury. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard KL, Filali M, Prefontaine P, Rivest S. Toll-like receptor 2 acts as a natural innate immune receptor to clear amyloid beta 1-42 and delay the cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5784–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1146-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor TM, O’Connell J, O’Brien DI, Goode T, Bredin CP, Shanahan F. The role of substance P in inflammatory disease. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201:167–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinstock JV, Blum A, Walder J, Walder R. Eosinophils from granulomas in murine schistosomiasis mansoni produce substance P. J Immunol. 1988;141:961–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambrecht BN. Immunologists getting nervous: neuropeptides, dendritic cells and T cell activation. Respir Res. 2001;2:133–8. doi: 10.1186/rr49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burg M, Zahm DS, Knuepfer MM. Immunocytochemical co-localization of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in afferent renal nerve soma of the rat. Neuroscience letters. 1994;173:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fehrenbach K, Port F, Grochowy G, et al. Stimulation of mast cells via FcvarepsilonR1 and TLR2: the type of ligand determines the outcome. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2087–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heib V, Becker M, Taube C, Stassen M. Advances in the understanding of mast cell function. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:683–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garza A, Weinstock J, Robinson P. Absence of the SP/SP receptor circuitry in the substance P-precursor knockout mice or SP receptor, neurokinin (NK)1 knockout mice leads to an inhibited cytokine response in granulomas associated with murine Taenia crassiceps infection. J Parasitol. 2008;94:1253–8. doi: 10.1645/GE-1481.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svensson A, Kaim J, Mallard C, Olsson A, Brodin E, Hokfelt T, Eriksson K. Neurokinin 1 receptor signaling affects the local innate immune defense against genital herpes virus infection. J Immunol. 2005;175:6802–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh DT, Weg VB, Williams TJ, Nourshargh S. Substance P-induced inflammatory responses in guinea-pig skin: the effect of specific NK1 receptor antagonists and the role of endogenous mediators. British journal of pharmacology. 1995;114:1343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joachim RA, Handjiski B, Blois SM, Hagen E, Paus R, Arck PC. Stress-induced neurogenic inflammation in murine skin skews dendritic cells towards maturation and migration: key role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1/leukocyte function-associated antigen interactions. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1379–88. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]