The use of cyclosporine (CyA) has resulted in significantly improved graft survival rates in renal transplantation. 1–5 However, the incidence of allograft rejection with CyA remains as high as 69%.5 Although CyA monotherapy has proven feasible in some studies,6 recent attempts to use CyA alone in kidney transplant recipients have shown some significant disadvantages, namely increased severity of rejection episodes and more pronounced nephrotoxicity.5 FK 506 is an experimental immunosuppressant that has yielded encouraging results in early trials of liver, heart, and, more recently, renal transplantation. 7–11 The apparent advantages of FK 506 in these early experiences include the ability to taper steroids aggressively to the point of permitting FK 506 monotherapy in as many as 60% of renal transplant recipients with no increased risk of rejection episodes.11 FK 506 has also been used successfully to salvage liver transplants rejecting under CyA immunosuppression.12 We have recently begun evaluating the utility of FK 506 conversion in renal allograft recipients with failing grafts on CyA. A total of 35 patients were entered into this pilot study, the results of which are reported herein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

There were 20 male patients and 15 females, with a mean age of 32.6 ± 14 years (range 8 to 73 years). Twenty-eight patients had undergone primary renal transplantation and seven had been retransplanted (5 second, 1 third, and 1 fourth transplants). Twenty-four were recipients of cadaveric renal transplants (CAD) and 11 were from living-related donors (LRD).

Indications for FK 506 Conversion

Patients considered for conversion to FK 506 had an initial diagnosis of uncontrolled rejection and/or other complications associated with CyA and/or steroid therapy (Table 1). Such complications included postoperative hypertension (diastolic blood pressure > 100 mm Hg despite diuretics) and steroid-induced diabetes mellitus. In the early part of the series, patients with chronic rejection on CyA therapy were also considered for FK 506 conversion. Prior to FK 506 conversion, maintenance immunosuppression consisted of CyA and prednisone in all patients, with (n = 16) or without (n = 19) azathioprine (AZA). All 23 patients with the diagnosis of acute rejection had additionally received bolus high-dose steroid therapy, and nine of these (39%) had received one (n = 7) or two (n = 2) courses of OKT3 prior to FK 506 conversion. Sixteen patients were referred to us for FK 506 conversion from other centers where they were deemed to be losing their grafts: 19 patients were entered from our own institution. All patients had received CyA doses maximized to tolerable levels.

Table 1.

Conversion From CyA to FK 506 in 35 Renal Transplant Recipients

| Indication for FK 506 Conversion | No. Patients (%) | No. Successful Conversions (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ongoing acute rejection* | 24 (69) | 17 (71) |

| Chronic rejection | 6 (17) | 0 (0) |

| CyA toxicity | 3 (9) | 1 (33) |

| Steroid complications† | 2 (5) | 2 (100) |

| Total | 35 | 20 |

Two patients had severe vascular rejection with ischemic infarction and failed conversion.

One patient had steroid-induced insulin dependent diabetes, and one patient wished to be tapered off prednisone because of marked obesity.

Preconversion Diagnostic Evaluation

All patients considered for conversion to FK 506 were subjected to Doppler ultrasound and radionuclide flow study of the renal allograft to rule out a technical cause of allograft dysfunction. Renal allograft biopsies were performed in all but the two patients who were converted to FK 506 because of steroid-related complications. The pathologic diagnosis prior to conversion was chrome rejection in six patients, interstitial fibrosis in three, severe vascular (humoral) rejection in two, and acute cellular rejection (ACR) in 22. Two of the patients with biopsy-proven ACR also had components of vascular rejection.

FK 506 Conversion Therapy

Because of previous evidence of adverse effects with combined FK 506 and CyA therapy in liver allograft recipients,12 all patients underwent a simple switch (“clean conversion”) from CyA to FK 506. All patients were given a standard daily oral dose of 0.3 mg/kg/d in divided doses every 12 hours starting 12 hours after the last CyA dose had been administered. In addition, 11 patients received parenteral doses of FK 506 of 0.025 to 0.1 mg/kg/d overlapping with the first 1 to 4 days of oral therapy. Dose adjustments of FK 506 were based upon monitoring of serum trough levels by ELISA13 to achieve a 12-hour trough level of 1.0 to 2.0 ng/mL, and also by adjustment according to clinical and biochemical parameters.

RESULTS

Successful conversion from CyA to FK 506 was defined as a return to baseline serum creatinine (SCR), and/or improvement on postconversion renal allograft biopsy, and/or freedom from dialysis if the patient was dialysis-dependent at the time of conversion. Of the 35 patients entered into this study, successful conversion according to these criteria was achieved in 20 (57%). Early in this series, FK 506 conversion was attempted in six patients with evidence of chronic rejection on preconversion biopsy, all of whom subsequently lost their grafts. Of the remaining 29, one patient without rejection desired FK 506 conversion in order to eliminate steroid therapy. This patient has since been tapered to 2.5 mg of prednisone daily and is now 7 months postconversion. A second patient with steroid-induced insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is currently taking no prednisone and is requiring significantly less insulin. Of the remaining 27 patients. 24 had ongoing acute rejection on preconversion biopsy and three had interstitial fibrosis. Of the 24 cases with acute rejection. 17 (71%) were successfully rescued. Two of these successes had evidence of a vascular component of rejection on preconversion biopsy. Eleven patients with acute rejection prior to conversion had failed at least one course of OKT3 (average length of treatment 10 days) prior to FK 506 conversion, which was carried out at a median of 18 days following the last dose of OKT3. Nine patients in this series (26%) were already dialysis-dependent at the time of conversion. Of these, six patients now have functioning grafts with serum creatinines of 2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.5, and 6.6 mg/dL, respectively. The clinical course of one such patient is depicted in Fig 1.

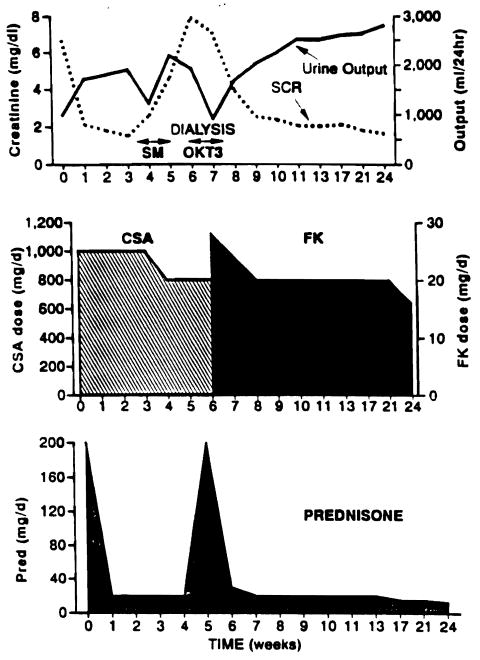

Fig 1.

Clinical course of patient no. 27. The patient is a 30-year-old male with ESRD secondary to a connective tissue disorder with 0% panel reactive antibody undergoing primary transplantation. A severe rejection occurred 4 weeks after transplantation, which did not respond to a course of high-dose corticosteroids. The patient required dialysis on five occasions after the rejection episode began. He received two doses of OKT3 but had a severe reaction to the drug (disorientation, seizures, fluid overload) and this was discontinued. He was switched to FK 506 on day 33 following transplantation. The patient currently has a functioning graft with a SCR of 1.7 mg/dL.

Successful conversion was achieved in 12 of 24 (50%) CAD and S of 11 (73%) LRD recipients. There was a slightly greater proportion of patients with ACR as the preconversion diagnosis in the LRD group (8/11, 73%) compared to the CAD group (16/24,67%). Patients initially immunosuppressed with CyA and prednisone (n = 19) or CyA, prednisone, and AZA (n = 16) had equivalent success rates of 58% and 56%, respectively. Of the 28 primary transplantations, 18 (64%) were successfully converted: two of the five retransplants (40%) were successes. Of 16 patients referred from other centers for FK 506 conversion, 13 (81%) were rescued compared with 7/19 (37%) successes in patients from our own institution. As described earlier, the first six patients from our own institution were early attempts that all failed conversion for chronic rejection, which in retrospect was most likely an ill-advised indication for conversion to FK 506.

Morbidity and Mortality

There were three deaths in this series, all occurring in patients whose grafts had been lost. One patient died 8 months postconversion while on dialysis (unknown etiology), one from overwhelming sepsis at 7 months, and one patient suffered a massive fatal intracranial hemorrhage 4 months after conversion. The remaining complications in this series are shown in Table 2. Three patients referred for conversion to FK 506 had experienced prior complications. One patient had suffered a perforated duodenal ulcer after high-dose bolus steroid therapy for rejection. Following surgical correction of this complication, she continued to have rejection of the allograft. This patient was subsequently switched successfully to FK 506 with no further complications. A second patient developed CMV gastntis following treatment of rejection with high-dose steroids and OKT3. He was converted to FK 506 while being treated with ganciclovir, with successful results. A third patient referred for FK 506 conversion had developed a ureteral leak 29 days posttransplant. The patient was successfully switched to FK 506 2 months after ureterone-ocystostomy following a severe rejection episode that was resistant to both high-dose steroids and a to-day course of OKT3. Other complications following FK 506 conversion are listed in Table 2. None of these resulted in any mortality and could not be directly related to FK 506 conversion.

Table 2.

FK 506 Salvage Therapy: Complications

| Pre-FK 506 Conversion | No. | Post-FK 506 Conversion | No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perforated duodenal ulcer | 1 | CMV pneumonitis | 1 |

| CMV Gastritis | 1 | Diabetes—oral medication | 1 |

| Urine leak | 1 | Diabetes—insulin dependent | 1 |

| Epistaxis | 1 | ||

| Cecal perforation | 1 | ||

| Hypertension | 1 | ||

| Bacterial pneumonia | 1 |

Renal Function

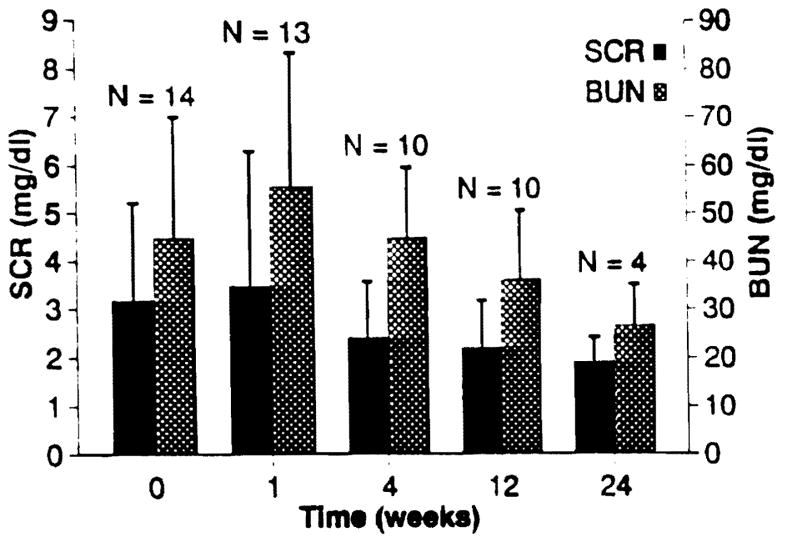

The mean SCR prior to FK 506 conversion in the successful switches was 3.2 ± 2.0 mg/dL, excluding the six patients who were on dialysis at the time of FK 506 conversion. The average SCR after FK 506 conversion was 2.3 ± 1.2 mg/dL, with all 20 grafts functioning (including the six on dialysis at the time of conversion). Excluding the six patients on dialysis at the time of conversion, the average SCR post-FK 506 conversion was 1.9 ± 0.5 mg/dL. The time course of improvement in renal function in relation to FK 506 conversion is illustrated in Fig 2.

Fig 2.

Renal function in patients with functioning allografts following conversion from CyA to FK 506, excluding those patients on dialysis at the time of conversion.

Postconversion Immunosuppression

All patients switched from CyA to FK 506 were taking prednisone prior to conversion (average dose 17.7 ± 9.9 mg/d). At last follow-up (mean 8.9 months), the average prednisone dose for the 20 patients with functioning grafts is 6.6 ± 6.1 mg/d. All 20 patients successfully convened remain on FK 506, with seven patients (35%) on FK 506 monotherapy.

Biochemistry

Mean serum uric acid in the 35 patients converted to FK 506 was 7.5 ± 3.5 mg/dL preconversion and 7.9 ± 2.1 postconversion. Glucose was 100.3 ± 21.1 mg/dL preconversion and 111.8 ± 65.1 mg/dL postconversion. One patient became insulin dependent following conversion and a second patient requires an oral hypoglycemic agent. Mean cholesterol and triglycerides were 189.0 ± 42.0 and 225.8 ± 107.4 preconversion and 198.0 ± 8.2 and 222.0 ± 95.7 postconversion, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Despite the enhanced graft survival since the advent of CyA in renal transplantation, the incidence of rejection episodes remains high in most reported series.1–5 One of the primary stated aims of multiple drug regimens for immunosuppression is the achievement of less toxicity without an increased risk of rejection. Unfortunately, even with triple therapy based on CyA, rejection episodes occur with enough frequency and severity as to result in even the most conservative practitioner occasionally overimmunosuppressing with excessive steroids and/or antilymphocyte preparations, with their attendant complications. It would be preferable to use an alternative immunosuppressive agent that was potent enough to reverse recalcitrant rejection without resorting to the use of excessive doses of steroids and antilymphocyte preparations. The results of this study indicate that FK 506 may possess these advantages. In 17/24 (71 %) of the patients who were losing their grafts owing to ongoing acute rejection. FK 506 conversion resulted in graft salvage. Ten of these 17 patients (59%) had already failed OKT3 treatment, and all 17 patients had been previously treated with bolus steroid therapy. Steroid tapering was accomplished in the majority of these patients postconversion, and seven patients are currently on FK 506 monotherapy. These results illustrate the potency of FK 506 as an immunosuppressant, but the incidence and severity of complications after FK 506 conversion are also quite tolerable. In this regard, FK 506 appears to be unique as a novel nonsteroidal immunosuppressant that can be used to reverse acute rejection in renal transplantation. Other than its proven in vitro potency, it is not clear what properties of FK 506 other than inhibition of IL-2 and IL-4 synthesis might account for these observations. Recent studies by Wang et al 14 suggest that FK 506 spares IL-10 production: perhaps other mechanisms are also involved and will await further investigation.

In conclusion, FK 506 can be used to salvage renal allografts failing CyA-based immunosuppression due to ongoing acute rejection. In certain instances, steroid therapy may be entirely eliminated following FK 506 conversion while preserving adequate immunosuppression and graft function.

References

- 1.The Canadian Multi-Center Transplant Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:809. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommer BG, Henry M, Ferguson RM. Transplantation. 1987;43:85. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198701000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilney NL, Milfor EL, Carpenter CB, et al. Transplant Proc. 1986;18(suppl 1):179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matas AT, Tellis VA, Quinn TA, et al. Transplantation. 1988;45:406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarantino A, Aroldi A, Stucchi L, et al. Transplantation. 1991;52:53. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Multicentre Trial Group. Lancet. 1983;2:986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Todo S, Fung JJ, Demetris AJ, et al. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starzl TE, Todo S, Fung J, et al. Lancet. 1989;2:1000. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starzl TE, Fung J, Jordan M, et al. JAMA. 1990;264:63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armitage JM, Kormos RL, Griffith BP, et al. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:1149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro R, Jordan M, Fung J, et al. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:920. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fung JJ, Todo S, Jain A, et al. Transplant Proc. 1990;22(suppl 1):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K, Kobayashi M, Hashimoto K, et al. Transplant Proc. 1987;19(suppl 6):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Zeevi A, Tweardy DJ, et al. Transplant Proc. 1991;23 (this issue) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]