ABSTRACT

The management of enterocutaneous fistulas continues to be a challenging postoperative complication. Understanding the anatomy of the fistula optimizes its evaluation and management. Diagnostic radiology has always played an important role in this task. The use of plain radiography with contrasted studies and fistulograms is well documented in the earliest investigations of fistulas and they continue to be helpful techniques. The imaging techniques have evolved rapidly over the past 15 years with the introduction of cross-sectional imaging, ultrasound and endoscopy. The purpose of this chapter is to review both the diagnostic and therapeutic roles of fistulograms, small bowel follow-through, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, and endoscopy in the setting of acquired enterocutaneous fistulas.

Keywords: Enterocutaneous fistula, fistulogram, small bowel follow-through, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging

Imaging studies are integral to the diagnosis of an enterocutaneous fistula (ECF). Early series describing the presence of ECFs date back to the 1930s, during which radiographic studies were used to verify their presence.1,2,3 As early as 1929, Frazier and Ginzburg described the use of iodized rape-seed oil for the use of roentgenographic imaging of intraluminal structures in the English literature.4,5 By the 1940s, when large series of ECFs were published, fistulography and injection of the fistula were standard in the evaluation of ECF.6,7 Since that time, techniques have expanded substantially and fistulograms, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and endoscopy are all used to evaluate and even treat fistulas.

ECF imaging is not a purely academic endeavor. Radiographic studies provide important details on the etiology of ECF and vital clues to aid in successful treatment. The role of radiology is to define the anatomy, evaluate associated processes, and provide therapeutic alternatives for treatment.

Imaging studies can confirm the anatomic origin of the fistula. Although clinical data can offer estimates of location based on quality and quantity of effluent, radiographic studies provide additional details. A proximal versus distal location may affect the nutritional needs and fluid requirements of patients. In postoperative patients, details regarding the source of the fistula including anastomotic leak, missed enterotomy, or a primary disease source can be helpful in supporting and treating the patient.

Anatomic details of the fistula, including diameter, length, and presence of side branches are provided by imaging studies. Historically, ∼30% of ECFs will close with nonoperative management, potentially saving the patients from significant morbidity and mortality of a technically challenging operation.8 Long and narrow fistulas are the most likely to heal spontaneously, although such closure of short wide-mouthed fistulas is less promising.

The etiology of the fistula is often discovered on imaging studies. A litany of causes for fistulization includes inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, or adhesions. Without identification and treatment of these causes, conservative management of the fistula is unlikely to be successful. Associated abscesses must be treated to prevent sepsis and allow for closure of the fistula. Intraabdominal abscesses are associated with a fistula ∼44% of the time.9 Imaging in these cases provides not only for diagnosis, but also for percutaneous treatment.

The successful treatment of ECF with radiographic and endoscopic techniques is a burgeoning field in this era of minimally invasive surgery. Percutaneous cannulation, control of ECF output and treatment of associated abscesses have been described since the 1970s, and their role and success are continuing to grow.10,11 Endoscopic treatment of gastrocutaneous fistula is expanding to the treatment of ECF.12,13

This chapter will review common modalities for imaging of enterocutaneous fistula and discuss techniques and advantages associated with each. In addition, the applications for radiological and endoscopic treatment of ECF will be reviewed.

CONTRAST STUDIES: FISTULOGRAMS, SMALL BOWEL FOLLOW-THROUGH

Fistulograms

Historically, fistulograms or sinograms have been the first choice in the evaluation of ECFs. Fistulograms are the most rapid and direct method of linking a cutaneous opening with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.7,14 In the absence of sepsis, fistulograms may be the only imaging study needed.15

The technique of a fistulogram is simple. Prior to injection of contrast, a plain film of the abdomen is taken. This documents the presence of surgical staples, clips, or pathology, and maps the fistula with respect to anatomic features. The external opening is cannulated for injection of contrast. Multiple techniques are reported including the use of an angiocatheter, Foley catheter, nasogastric tube, or pediatric feeding tube depending on size and diameter of the external orifice (Fig. 1).7,14,16 When the external opening is capacious, a rubber plug may be used to prevent retrograde leakage of contrast.17

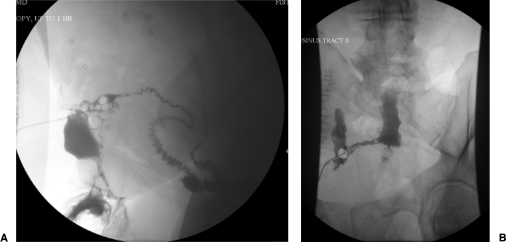

Figure 1.

Two images depicting fistulograms with fluoroscopy. Note the Foley catheter balloon used to minimize backward flow of contrast and the contrast filled small bowel.

After initial evaluation of the tract, angiocatheters and wires may be manipulated to further elucidate abscess cavities and side branches. Spot radiographs or fluoroscopy in different projections are performed to best delineate the tracts. Multiple views may be obtained to provide more anatomic detail (Figs. 2, 3).18 The patient may be moved in different positions to allow for dependent drainage and improved visualization.

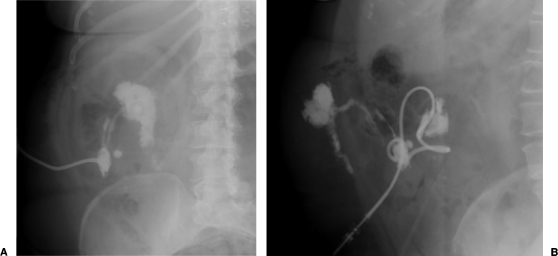

Figure 2.

Two plain film images of a fistulogram in the same patient status postappendectomy depicting an enterocutaneous fistula to the terminal ileum.

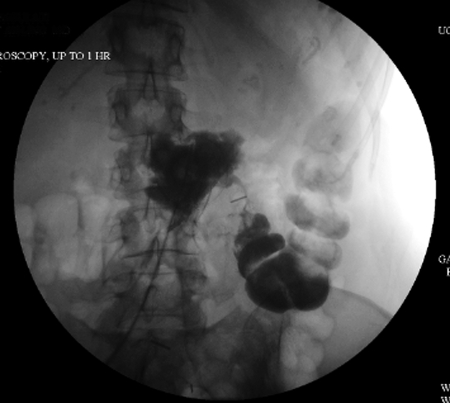

Figure 3.

Fluoroscopic image after percutaneous contrast administration in a patient with enterocutaneous fistula confirmed to be originating at the anastomosis of a transverse colon resection. The midline contrast collection identifies an abscess and the thin trail of contrast leads to the transverse colon. Note the surgical clip along the fistula tract.

Initial contrast injection should be performed gently as adjacent soft tissues are often fragile. Aggressive injection may injure tissues, cause false passages, and fail to demonstrate subtleties within the tract. Injuries to bowel and rupture of a pancreatic pseudocyst have been reported during injection of fistula tracts.14 Practitioners should be aware that debris and large abscesses may limit visualization of fistulograms and result in incomplete or inaccurate results.19

The choice of contrast media may also affect visualization of the fistula tract. Two classes of contrast media are commonly used to evaluate the tract, each with particular risks and benefits. Barium is a nonwater soluble media with high radiographic density, ISO osmolarity, and an inert nature. Barium provides high-quality mucosal images, demonstrating areas of inflammation and the presence of fistula tracts with good accuracy.20 Unfortunately, if extravasated, barium causes significant peritoneal inflammation, including foreign body granulomas and peritoneal adhesions.21,22

Aqueous contrast agents, such as Gastrografin, are hyperosmolar and water-soluble. Water-soluble agents provide less mucosal detail; areas of inflammation, mucosal projections and fistula tracts themselves may be missed. In addition, iodinated media causes acute pulmonary edema if aspirated. However, Gastrografin is rapidly absorbed within the peritoneal cavity if extravasated with minimal inflammation.23 To minimize risk and maximize benefits, water-soluble contrast material is often injected initially, followed by barium if no extravasation is seen and additional information is required.16,24,25

The benefits of fistulograms include provision of rapid and direct information with minimal patient discomfort or cost. Fistulograms provide real-time images that can be evaluated immediately. They do not require the ingestion of contrast or intravenous injections and are relatively easy and inexpensive to perform.

Despite these strengths, fistulograms provide limited supplementary information. Often, they fail to define the presence of disease upstream or downstream from the fistula, which may be necessary for appropriate treatment planning. They may fail to provide the anatomic location of the ECF within the GI tract. Edema, debris, or a large abscess may hinder fistulograms, preventing contrast flow into the intestinal lumen.19,26 In the presence of sepsis, fistulogram is contraindicated, as injection may cause dissemination of bacteremia.15,27

Despite these limitations, fistulograms are sufficient for diagnosis in most cases.15,16,28 Fistulograms provide sufficient data in up to 57% of cases. When information is deemed unsatisfactory, a fistulogram can be followed by additional imaging studies such as small bowel follow-through (SBFT) or computed tomography.25

Small Bowel Follow-Through and Small Bowel Enterography

When the fistulogram fails to elucidate the source or etiology of the ECF, SBFT studies may be performed. SBFT provides a more global view of the intestinal tract. The primary benefit of the SBFT is evaluation of the distal bowel and identification of intraluminal causes of the ECF.

To perform, patients swallow contrast and serial films are performed as the contrast moves through the intestinal tract. SBFT can usually successfully identify the anatomic source of the tract (Fig. 4). Multiple views are typically taken to optimize visualization. Ideally, barium is used for contrast as Gastrografin can be diluted as it moves distally through the GI tract. Patients with concerns for intestinal perforation should not receive barium until imaging has definitively ruled out extravasation.

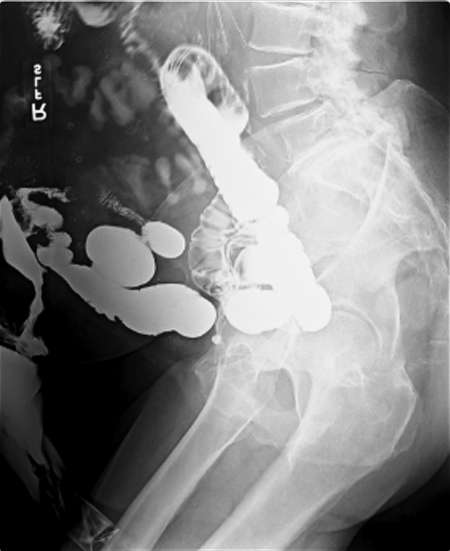

Figure 4.

Small bowel follow-through in a patient who had undergone multiple operations for an abdominal hernia. Note the contrast delineating the fistula tract to the left of the image and filling the colostomy bag.

SBFT may fail to identify the fistula location for several reasons. If the majority of the contrast passes swiftly, or if the intraluminal orifice is small or obstructed, fistulas may be missed. If the fistula is located distally in the small bowel or colon, previously opacified loops of bowel may complicate visualization of the fistula. In addition, SBFT requires considerable time and effort by the patient. Typically 500 to 600 mL of barium are ingested for the study. The time to perform the SBFT is over 2 hours, significantly longer than CT or MRI.29

No sensitivity data for fistulas and SBFT is available. SBFT is believed to be less sensitive than newer imaging methods such as MRI or CT enterography. In a study comparing evaluation of inflammation in Crohn disease, SBFT was significantly less accurate than CT or MR enterography. Although positive predictive value (PPV) was 100% for SBFT, negative predictive power (NPV) was only 50%.29 Lipson found SBFT to be only 85% sensitive to intraluminal disease when compared with ileoscopy.30

Small bowel enterography (SBE) is a similar modality, but provides greater mucosal detail than traditional SBFT. SBE uses biphasic imaging, double contrast, and distension of the small bowel to evaluate for presence of disease with sensitivity of greater than 70%.31 For patients with complicated intraluminal disease, such as Crohn disease, SBE is the gold standard for evaluation. However, SBE requires onerous placement of a nasogastric tube, prolonged time in radiology and extensive use of radiologists. As with the traditional SBFT, SBE may still fail to identify the internal source of fistula if edema, debris, or a small orifice exists.

CROSS-SECTIONAL IMAGING: COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Cross-sectional imaging provides complementary information to conventional contrast studies. Although cross-sectional imaging can sometimes locate a fistula within the GI tract, its advantages lie in the identification of extraluminal pathology, downstream disease and inflammation. Fluoroscopic imaging is generally poor at identifying noncontiguous lesions, which may require treatment to allow the fistula to heal.14,32 The presence of abscesses, obstruction or inflammation can contribute to the creation of ECF, leading to failure of nonoperative management and to sepsis. For these reasons, cross-sectional imaging is used in the initial evaluation of ECF, as an adjunct when patients fail to respond to initial therapy, and for preoperative planning.26,33

Computed Tomography and CT Enterography

CT scans should be performed with intravenous and oral contrast unless contraindicated. Intravenous (IV) contrast demonstrates inflammation whereas oral contrast differentiates loops of bowel from extraluminal collection or abscesses. Abscesses may be identified by air-fluid levels, air bubbles, or contrast extravasation. CT also provides the advantage of a modality that allows guidance of percutaneous drainage.9,11,19,28,34,35 Fistulas opacify proximally and distally to the tract, where contrast accumulates.

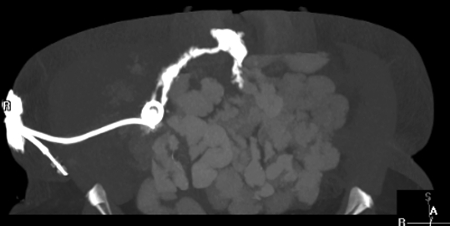

CT enterography (CTE) has been used to increase sensitivity of luminal disease. The difference between traditional CT and CTE is the type of attenuation obtained from the contrast agent used. In traditional CT, “positive” contrast such as barium, which is of high attenuation, will appear white on CT and can potentially delineate fistula tracts (Figs. 5, 6). CTE utilizes “negative” contrast, which appears dark, allowing for distention of the bowel. With the concomitant administration of IV contrast that will delineate mucosa, negative contrast provides additional information concerning the mucosa surrounding a fistula tract.

Figure 5.

Computed tomography for the same patient described in Figure 2.

Figure 6.

Computed tomography for a patient who developed an enterocutaneous fistula after an ileostomy takedown. The arrow points to the tract that leads to the small bowel.

CTE has greater sensitivity and accuracy when compared with traditional fluoroscopic enteroclysis for intraluminal findings, and better results for extraluminal findings.29 Smaller abscesses may be missed, however, on CTE, as negative contrast can make them difficult to distinguish from loops of bowel. These abscesses are often better visualized on traditional CT. SBE fails to demonstrate extraluminal disease unless in direct continuity with the bowel lumen or anatomically impinging on the bowel lumen.36 CTE has the advantage of being able to better discern disease located in close proximity to other bowel loops, which are difficult to visualize in fluoroscopic imaging. Reader variability is also decreased for CT and CTE when compared with fluoroscopic studies.29

Repeated use of CT raises concerns of radiation exposure. The average yearly exposure to radiation is ∼3 mSv (millisievert). An abdominal CT exposes the patient to 10 mSv, which is similar to the amount of exposure during a full-body CT. To compare, a plain film exposes the patient to ∼0.1 mSv. There are currently no prospective studies evaluating the cancer risk from routine CT scans, but available estimates place a small but finite increase in cancer risk with CT scan usage. Most studies regarding radiation exposure and its effect on cancer risk are typically based on populations exposed to high doses of radiation, such as atomic bomb survivors or calculations based from radiation risk estimates and prevalence of CT scan use.37,38 As such, caution regarding judicious use of radiation-based studies is essential, especially in regards patients with ECF who will likely require both multiple diagnostic and follow-up studies.

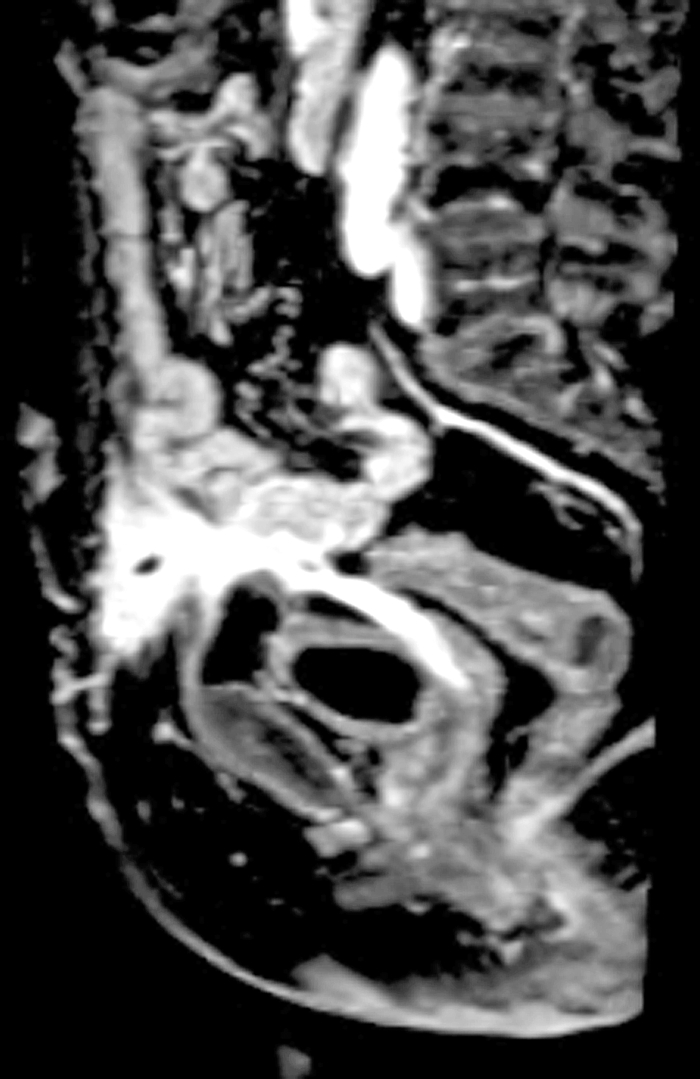

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and MR Enterography

MRI is a promising adjunct to primary imaging modalities. Its use in small bowel evaluation is beginning to be understood; MRI can identify extraintestinal complications, small bowel, and colonic disease. Most studies comparing MRI with other modalities are focused on perianal fistulas.34,39 Nevertheless, the use of MRI can be extrapolated for ECF evaluation.

MRI does not require bowel preparation. Instead, patients undergo a fasting period of ∼4 to 6 hours. For MR enterography (MRE), oral contrast, such as 2% barium sulfate, is consumed at different intervals of time, allowing for distention of the bowel lumen, which allows for optimal evaluation of bowel wall enhancement by the administered IV gadolinium.

Unlike CT, MRI has an increased ability with better soft tissue contrast to differentiate between inflammatory and stenotic disease. In the postoperative patient, edema or inflammation may be highlighted on T1-weighted images. Enhancement on T1 gadolinium images appears to be highly specific for active disease.40,41 Inflammation, unlike stenosis, may respond to conservative management and pharmacologic treatment.

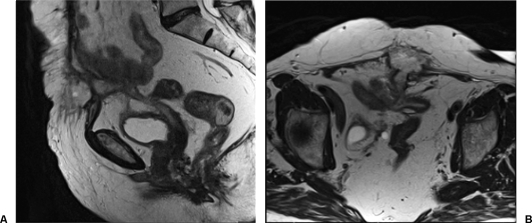

T-2 weighted images are particularly sensitive to the presence of fluid. High signal intensity on T2-weighted images is consistent with fistula. MRI can effectively identify the internal orifice in the bowel wall and delineate the course of the fistula through muscle and hollow viscera. When compared with SBE, MRI was equally effective at identification of s (Figs. 7,8).42,43 Occasionally, however, other structures such as nerves and blood vessels with similar imaging qualities and may be mistaken for fistulas.

Figure 7.

Magnetic resonance imaging (T1 weighted, sagittal view) in a patient who developed an enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) after Hartmann's procedure for diverticulitis. The ECF is noted at the level of the skin, leading to an abscess and then leading to the pouch and the vaginal pouch. (The patient was also status posthysterectomy.)

Figure 8.

Magnetic resonance imaging (T2-weighted, sagittal view to left and axial view to right) for the same patient as Figure 7. The large fistula tract is seen with communication to the sigmoid pouch as well as the vaginal stump.

MRI has several benefits over fluoroscopy and CT imaging. MRI and MRE can allow for real-time evaluation of the bowel, compared with CTE, which only provides separate shots. This becomes an advantage for evaluating for a fistulous tract in the setting of peristalsis and intermittent collapse of bowel.44 MRI removes the risk of radiation exposure when compared with fluoroscopy or CT imaging. Decreased radiation is especially important in children and patients with chronic disease who may require serial imaging in their lifetime. MRI uses gadolinium, rather than iodinized contrast and is therefore useful in those patients with iodine allergies and mild renal failure.

One major limitation of MRI when compared with CT involves the temporal and spatial resolution of GI tract imaging. Motion artifact from bowel peristalsis can degrade image quality. The superior temporal and spatial resolution of CT does not necessarily translate to superior sensitivity and specificity when compared with MRI, however. Further studies are necessary to determine optimal resolution for MRI imaging of the GI tract.41

Another limitation of MRI is the time required to obtain these high-resolution images. Typically, patients must remain perfectly still for periods ranging from 30 to 120 minutes to prevent corrupted of images by motion artifact. The patient may be required to do several separate breath-holds of up to 15 seconds at a time to obtain optimal spatial and temporal images. MRI machines are typically tunnel-like structures and patients with claustrophobia may be unable to tolerate the prolonged and confined nature of the MRI. In addition, MRI utilizes a powerful magnet, and presence of pacemakers, clips, or shrapnel are contraindications. Access to an MRI scanner limits its use when compared with the CT scans. Finally, the cost of MRI imaging limits its repeated use at this time.

ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound (US) plays a role in the evaluation of ECF. Although, US has been successfully used in the assessment of Crohn disease, identification of bowel wall thickening, and evaluation of stenosis, the major uses of US are in repeat imaging and localization of abscesses.45 Limited patient preparation and the noninvasive, nonradiating nature of the study make US a patient-friendly option. US provides an inexpensive, portable, and relatively rapid imaging modality in ECF evaluation.

Substantial data are available for the accuracy of US in evaluating both the presence of inflammation and the location of small bowel disease. In as study by Hollerback et al, sensitivity of US for small bowel disease was 86% when compared with CT scan and agreement with fluoroscopic exams occurred in 86 to 93% of cases.46 Parente et al found an 85% sensitivity rate with fluoroscopic, CT, and endoscopic studies. Abnormalities were most often missed in the duodenum, jejunum, and transverse colon.45,46

Less data are available specifically for the existence of ECF and US use. Parameters for defining ECF have been published. Gasche et al defined a fistula as a hypoechoic periintestinal lesion arising in the area of bowel wall thickening.47 They defined lesions of less than 2 cm as a fistula, whereas lesions greater than 2 cm were defined as abscesses. Sensitivity of fistula identification was 87%, with specificity of 90%. Simultaneously, Maconi et al evaluated the sensitivity of US at identifying ECF.48 They defined a fistula as a hypoechoic or anechoic duct like structure with fluid and or air content localized between the skin and intestinal loops.

To further increase sensitivity, hydrogen peroxide may be injected through the skin orifice. Results were compared with a standard fistulogram and surgical treatment, when applicable. Of 17 patients, US alone was able to demonstrate the internal opening in only 5 of 17 cases.48 With hydrogen peroxide, 15 of 17 studies demonstrate the presence of opening. Fistulograms demonstrated the opening in only 64% of those cases. Abscesses were noted in 5 of 17 patients on CT scan and all were identified by ultrasound.

Limitations of US include operator dependency, patient habitus, and the difficulty of evaluating certain portions of the small bowel including duodenum and jejunum. Alexander et al attempted US on 12 patients and 75% were found to have incomplete exams secondary to the presence of bowel gas, surgical incisions and dressings.14 Obesity and ileus also prevent reliable imaging.18,46 US has not been shown to be an effective primary or solitary imaging modality and generally requires adjunctive modalities for further information.14

ENDOSCOPY

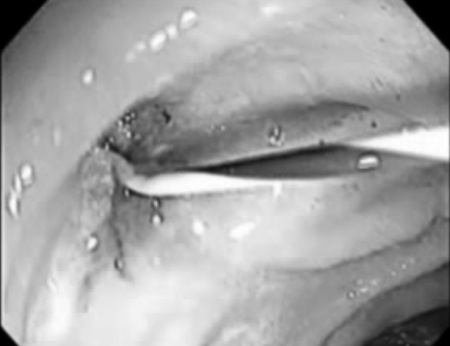

Endoscopy for Diagnosis

Endoscopy is the gold standard for evaluation of mucosal disease in the setting of inflammatory disease such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. This modality has rarely been reported as a diagnostic modality for ECF. The inherent challenge lies in identification of the intraluminal orifice of the fistula, which is difficult without other imaging modalities (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Cannulation of internal orifice of an enterocutaneous fistula at previous jejunostomy site.

Endoscopic Treatments of Fistula

Although its role may be limited in evaluation of ECFs, endoscopy has provided a unique minimally invasive therapeutic option for fistula treatment. Interventions using fibrin tissue or glue sealant and the use of stenting have emerged as options for treatment of ECF.

Cadoni et al first described the treatment of duodenocutaneous fistulas with fibrin tissue sealant in the 1990s and the technique was quickly expanded to treat gastrocutaneous fistulas for patients after gastric bypass or vertical banded gastroplasty.49,50,51,52,53 Gonzalez-Ojeda et al reported the use of fibrin glue in treatment of gastrocutaneous fistulas with significantly shorter time to fistula closure of 7 days compared with those treated conservatively, with those fistulas closing a mean of 30 days.54

The success of fibrin glue, which is typically a combination of thrombin and fibrinogen, in treatment of fistulas depends on complete occlusion of the tract and in-growth of granulation tissue. The thrombin cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, promoting fibroblast cells migration and the growth of granulation tissue. The glue is then absorbed over 4 weeks and replaced with scar tissue.55

The use of fibrin glue in ECF has been described.56 Lamont et al successful treated four patients with 1 to 2 endoscopic injections of fibrin glue (Fig. 10).57 Rabago and colleagues published data on a heterogeneous group of 15 patients following upper and lower abdominal surgery.12 Their success rate was 86.6%, with patients requiring a mean of 2.5 applications of fibrin. Kwon had success with a single patient following a traumatic jejunocutaneous fistula with fibrin glue injection.18

Figure 10.

Injection of fibrin glue.

Fibrin application requires the endoscopic identification of the internal orifice. Rabago noted that fistulas smaller than 5 to 7 mm in size were rarely identified, and those larger than 2 cm were unlikely to heal, and injection may increase the risk of sepsis.12 When unable to identify the luminal defect, injection of dye may be performed simultaneously through the external orifice.56 Quick acting fibrin must be mixed during direct application and requires simultaneous injection from two catheters to prevent premature activation of the glue.58 Indeed, one of the limitations of fibrin glue application in fistula treatment is in the agent itself. The fibrinogen and thrombin coagulate immediately upon their mixture. The use of double-lumen catheters or alternate injection of each component is suggested for preventing coagulation before administration.12,55 Despite these alternative administrations of the components, coagulation can still occur prematurely when administered into large fistulous tracts, creating a dead space. Murakami et al describe successful closure of fistulas in 16 of 18 patients with a combination of thrombin diluted with normal saline to a concentration of 8.0 Units/mL and fibrinogen. In vitro studies confirmed no change in tensile strength even after this degree of dilution. Eleven of those 16 patients required two or more sessions, however. None of the patients successfully closed had recurrence at follow-up in one year.59 Fibrin glue is reported not to be as successful in the setting of tissues that are chronically infected, neoplastic or status-post radiation treatment, and these qualifiers applied to the two patients who were not successfully treated in the Murakami and associates study.12,54,59,60

Rabago recommended patients be treated conservatively with bowel rest and antibiotics for 10 to 14 days after surgery to decrease inflammation, and that endoscopic treatment is attempted within 10–14 days of fistula formation. Fistulas that do not heal within 5 to 6 attempts, large volume fistulas, distal obstruction and Crohn disease are unlikely to respond to fibrin glue treatment.12 Most studies report a mean application of two to four treatments, with individual patients requiring as many as nine treatments.12,57,58 Although these studies report high success in the treatment of low-output fistulas, they include small numbers of patients. Randomized studies with larger populations are necessary.

Other materials have been used in management of ECF in numerous case studies. Khairy et al and Lisle and colleagues described use of Gelfoam (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY).61,62 Collagen plugs, coils with fibrin glue and Surgisis (Cook Biotech, West Lafayette, IN) have all been successfully used in individual cases of various types of fistulas (Fig. 11).63,64 One case reported by de Hoyos et al, describes colonoscopic placement of endoloops into the tract, with total closure of the wound at 6 months.65

Figure 11.

Control of endoscopically placed Surgisis (Cook Biotech, West Lafayette, IN) at external orifice.

The use of endoscopically placed self-expanding silicone stents has also been investigated recently in the setting of colostomy-related fistulas.13,18 The stents function to divert the stool stream to remote healing. In a select population, stent placement can provide an additional therapeutic option, whether by promoting complete healing of the fistula or improving management of fistula output. Kwon et al successful used covered metallic stents to treat two patients: a colocutaneous fistula after left colectomy and postoperative fistula after Bilroth I.18 Nikfarjam demonstrated the use of stents for distal colostomy fistulas (Fig. 12).13 Stent placement allowed for healing of the midline wound. One patient had complete healing of the fistula; withdrawal of care was performed for the second patient with terminal disease.

Figure 12.

Stent placed into distal colostomy fistula.

The advantages of endoscopic treatment include avoiding the morbidity of surgery and allowing for potential reduction of hospital length of stay, although further data are necessary. Risks of endoscopic fibrin injection include occasional allergic reaction to bovine aprotinin, a component of most commercially available fibrin products and isolated reports of air pulmonary embolism, in thoracic fistula. Stenting of the fistula appears to be viable alternative in some situations. Stent migration, obstruction, and perforation have occurred with intraluminal colonic stenting and further data should be obtained to evaluate long-term results.

PERCUTANEOUS IMAGE-GUIDED TREATMENT OF ENTEROCUTANEOUS FISTULAS

The technique of percutaneous drainage of abscesses was first described in 1977 by Grovall et al.66 Fistulas were noted to be associated with abscess in ∼38 to 44% of cases.6,67 van Sonnenberg and McLean described the percutaneous treatment of ECFs in 1982.11,68 Success of treatment has been described from 53 to almost 90% of cases.11,18,69

The technique for percutaneous drainage follows established principles. The fistula tract is evaluated using fluoroscopy. Frequently, multiple tracts interlace beneath the skin or an abscess may be noted. Internal fistulous collections may not be readily apparent. Initial attempts may be masked by debris or a large-sized abscess. Aggressive evaluation may increase the risk of sepsis and any abscess greater than 30 to 50 mL should be reevaluated after 2 to 3 days to attempt to find the internal orifice.

After identification of the internal orifice, the tract is cannulated with a red rubber catheter or angiocatheter. Guidewires may be employed to help guide catheters through the track to the internal opening. Initial studies involved placement of both T tube and drains into the abscess or surrounding tissue, although currently a variety of drains are used. Confirmation of placement through the fistula track is then confirmed with fluoroscopy and injection of contrast.

Keys to success have also been described. Prior to manipulation, antibiotics should be administered to prevent bacterial seeding. Catheters slightly smaller than the fistula tract are used to allow healing around the catheter.17 Initially, catheters are flushed daily to ensure patency and good flow. The tract and associated abscesses are evaluated weekly to ensure healing and determine whether the catheter may be downsized. Catheter changes may be performed over a wire to maintain the tract, and serial downsizing help to prevent formation of abscess cavity. Tubes may become occluded by debris or may migrate with time. Any significant change in quality or quantity of output warrants reimaging to confirm tube patency. Once drainage is predictable and regular, this can be stopped.

Removal of the catheter may occur when drainage has decreased to less than 10 cc per day and has become clear, and the patient's symptoms are improved.18 D'Harcour et al recommended clamping the tube for 48 hours prior to removal.17 Prior to removal, some authors recommend preremoval contrast injection studies to decrease the incidence of recurrent abscesses and repeat drainage, but this has not been widely employed.70

Reported results of percutaneous drainage have been largely successful. McLean described 12 ECF patients treated with large bore T tubes and external sump drains. Drainage required 2 to 4 weeks for abscess treatment and up to 3 months for fistula healing but no patient required surgical treatment.11 LaBerge et al reported an 83% success rate for 53 patients treated nonoperatively. Mean treatment time was 2 months. Low output fistulas healed in less time than high-output fistulas (mean 17 vs 41 days).70 D'Harcour published a series of 147 patients using percutaneous drainage techniques: 76% of fistulas were postoperative and 63% were high output. Percutaneous treatment was more successful in postoperative patients; high-output fistulas closed in 95% of postoperative patients versus 79% of primary fistulas. Low-output fistulas closed in 69% and 59% of postoperative and primary fistula patients, respectively. Mean times to closure were 39 days in postoperative patients and 51 days in primary fistula; 19% of patients ultimately required surgical treatment.17

CONCLUSION

Initial evaluation of an ECF begins with clinical suspicion followed by radiographic studies to define the anatomy of the fistula. Contrast studies in the form fistulograms best define the tract whereas cross-sectional imaging is useful for identifying potential management-altering factors such as abscesses and obstructions. Other modalities such as small bowel follow-through, CT enterography, MR enterography, and endoscopy have been used to evaluate associated intraluminal diseases such as Crohn disease, the presence of downstream obstruction, and inflammation.

These imaging modalities also play a role in therapeutic management of fistulas. Under fluoroscopic imaging, the fistula tract can be cannulated with downsizing of the catheter to promote circumferential healing. Imaging also allows percutaneous drainage of associated abscesses, which would otherwise retard resolution of the associated fistula. Endoscopy-assisted placement of fibrin glue and, more recently, placement of temporary stents have been described as alternatives to operative treatment of fistulas.

The wide variety of available imaging modalities provides the clinician a flexible approach to a classically challenging problem. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of the modalities provides the clinician with an armamentarium with which to better understand and therefore successfully manage the patient with an enterocutaneous fistula.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Drs. Raj Paspulati and Jeffrey Marks in obtaining the radiographic images.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rankin F W, Bargen J A, Buie L A. The Colon, Rectum, and Anus. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1932. p. 346.

- 2.Lewis D, Penick R M. Fecal fistula. Internat Clin. 1933;1:111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ransom H K, Coller F A. Intestinal fistula. J Mich State Med S. 1935;34:281. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frazier C H. The use of iodized rape-seed oil (campiodol) for rontgenographic exploration. Ann Surg. 1929;89(6):801–812. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192906000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginzburg L, Benjamin E W. Lipiodol studies of postoperative biliary fistulae. Ann Surg. 1930;91(2):233–241. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193002000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edmunds L H, Jr, Williams G M, Welch C E. External fistulas arising from the gastro-intestinal tract. Ann Surg. 1960;152:445–471. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196009000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segar R J, Bacon H E, Gennaro A R. Surgical management of enterocutaneous fistulas of the small intestine and colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1968;11(1):69–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02616751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schein M. What's new in postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas? World J Surg. 2008;32(3):336–338. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerlan R K, Jr, Jeffrey R B, Jr, Pogany A C, Ring E J. Abdominal abscess with low-output fistula: successful percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1985;155(1):73–75. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.1.3975423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gronvall J, Gronvall S, Hegedüs V. Ultrasound-guided drainage of fluid-containing masses using angiographic catheterization techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129(6):997–1002. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean G K, Mackie J A, Freiman D B, Ring E J. Enterocutaneous fistulae: interventional radiologic management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138(4):615–619. doi: 10.2214/ajr.138.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rábago L R, Ventosa N, Castro J L, Marco J, Herrera N, Gea F. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative fistulas resistant to conservative management using biological fibrin glue. Endoscopy. 2002;34(8):632–638. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikfarjam M, Champagne B, Reynolds H L, Poulose B K, Ponsky J L, Marks J M. Acute management of stoma-related colocutaneous fistula by temporary placement of a self-expanding plastic stent. Surg Innov. 2009;16(3):270–273. doi: 10.1177/1553350609345851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander E S, Weinberg S, Clark R A, Belkin R D. Fistulas and sinus tracts: radiographic evaluation, management, and outcome. Gastrointest Radiol. 1982;7(2):135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01887627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborn C, Fischer J E. How I do it: gastrointestinal cutaneous fistulas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(11):2068–2073. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickhardt P J, Bhalla S, Balfe D M. Acquired gastrointestinal fistulas: classification, etiologies, and imaging evaluation. Radiology. 2002;224(1):9–23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Harcour J B, Boverie J H, Dondelinger R F. Percutaneous management of enterocutaneous fistulas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(1):33–38. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.1.8659416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon S H, Oh J H, Kim H J, Park S J, Park H C. Interventional management of gastrointestinal fistulas. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9(6):541–549. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.6.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papanicolaou N, Mueller P R, Ferrucci J T, Jr, et al. Abscess-fistula association: radiologic recognition and percutaneous management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(4):811–815. doi: 10.2214/ajr.143.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley M J, Ghahremani G G, Rogers L F. Reappraisal of contrast media used to detect upper gastrointestinal perforations: comparison of ionic water-soluble media with barium sulfate. Radiology. 1982;144(2):231–237. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.2.7089273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisel R J, Donovan A J, Yellin A E. Experimental fecal peritonitis. Influence of barium sulfate or water-soluble radiographic contrast material on survival. Arch Surg. 1972;104(6):765–768. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180060015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ott D J, Gelfand D W. Gastrointestinal contrast agents. Indications, uses, and risks. JAMA. 1983;249(17):2380–2384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James A E, Jr, Montali R J, Chaffee V, Strecker E-P, Vessal K. Barium on Gastrografin: Which contrast media for diagnosis of esophageal tears? Gastroenterology. 1975;68:1103–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halasz N A. Changing patterns in the management of small bowel fistulas. Am J Surg. 1978;136(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas H A. Radiologic investigation and treatment of gastrointestinal fistulas. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76(5):1081–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70498-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gore R M, Balthazar E J, Ghahremani G G, Miller F H. CT features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(1):3–15. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.1.8659415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tio T L, Mulder C J, Wijers O B, Sars P R, Tytgat G N. Endosonography of peri-anal and peri-colorectal fistula and/or abscess in Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36(4):331–336. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollington P, Mawdsley J, Lim W, Gabe S M, Forbes A, Windsor A J. An 11-year experience of enterocutaneous fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91(12):1646–1651. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S S, Kim A Y, Yang S K, et al. Crohn disease of the small bowel: comparison of CT enterography, MR enterography, and small-bowel follow-through as diagnostic techniques. Radiology. 2009;251(3):751–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2513081184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipson A, Bartram C I, Williams C B, Slavin G, Walker-Smith J. Barium studies and ileoscopy compared in children with suspected Crohn's disease. Clin Radiol. 1990;41(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maconi G, Sampietro G M, Parente F, et al. Contrast radiology, computed tomography and ultrasonography in detecting internal fistulas and intra-abdominal abscesses in Crohn's disease: a prospective comparative study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1545–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frick M P, Feinberg S B, Stenlund R R, Gedgaudas E. Evaluation of abdominal fistulas with computed body tomography (CT) Comput Radiol. 1982;6(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/0730-4862(82)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draus J M, Jr, Huss S A, Harty N J, Cheadle W G, Larson G M. Enterocutaneous fistula: are treatments improving? Surgery. 2006;140(4):570–576. discussion 576–578. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koehler P R, Moss A A. Diagnosis of intra-abdominal and pelvic abscesses by computerized tomography. JAMA. 1980;244(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuya T, Hawes D R, Lu C C, Barloon T J. CT of abdominal abscess with fistulous communication to the gastrointestinal tract. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15(3):445–449. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sailer J, Peloschek P, Schober E, et al. Diagnostic value of CT enteroclysis compared with conventional enteroclysis in patients with Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(6):1575–1581. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brenner D J, Hall E J. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berrington de González A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet. 2004;363(9406):345–351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein C N, Greenberg H, Boult I, Chubey S, Leblanc C, Ryner L. A prospective comparison study of MRI versus small bowel follow-through in recurrent Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2493–2502. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh D M, Miao Y, Chinn R J, et al. MR imaging evaluation of the activity of Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(6):1325–1332. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fidler J. MR imaging of the small bowel. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45(2):317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koelbel G, Schmiedl U, Majer M C, et al. Diagnosis of fistulae and sinus tracts in patients with Crohn disease: value of MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152(5):999–1003. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiarda B M, Kuipers E J, Heitbrink M A, Oijen A van, Stoker J. MR enteroclysis of inflammatory small-bowel diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(2):522–531. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florie J, Wasser M N, Arts-Cieslik K, Akkerman E M, Siersema P D, Stoker J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of the bowel wall for assessment of disease activity in Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(5):1384–1392. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parente F, Greco S, Molteni M, et al. Role of early ultrasound in detecting inflammatory intestinal disorders and identifying their anatomical location within the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(10):1009–1016. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollerbach S, Geissler A, Schiegl H, et al. The accuracy of abdominal ultrasound in the assessment of bowel disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(11):1201–1208. doi: 10.1080/00365529850172575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gasche C, Moser G, Turetschek K, Schober E, Moeschl P, Oberhuber G. Transabdominal bowel sonography for the detection of intestinal complications in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1999;44(1):112–117. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maconi G, Parente F, Bianchi Porro G. Hydrogen peroxide enhanced ultrasound- fistulography in the assessment of enterocutaneous fistulas complicating Crohn's disease. Gut. 1999;45(6):874–878. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cadoni S, Ottonello R, Maxia G, Gemini G, Cocco P. Endoscopic treatment of a duodeno-cutaneous fistula with fibrin tissue sealant (TISSUCOL) Endoscopy. 1990;22(4):194–195. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shand A, Pendlebury J, Reading S, Papachrysostomou M, Ghosh S. Endoscopic fibrin sealant injection: a novel method of closing a refractory gastrocutaneous fistula. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(4):357–358. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang C S, Hess D T, Lichtenstein D R. Successful endoscopic management of postoperative GI fistula with fibrin glue injection: Report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(3):460–463. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toussaint E, Eisendrath P, Kwan V, Dugardeyn S, Devière J, Le Moine O. Endoscopic treatment of postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas after bariatric surgery with the use of a fistula plug: report of five cases. Endoscopy. 2009;41(6):560–563. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eleftheriadis E, Tzartinoglou E, Kotzampassi K, Aletras H. Early endoscopic fibrin sealing of high-output postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156(9):625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González-Ojeda A, Avalos-González J, Muciño-Hernández M I, et al. Fibrin glue as adjuvant treatment for gastrocutaneous fistula after gastrostomy tube removal. Endoscopy. 2004;36(4):337–341. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eleftheriadis E, Kotzampassi K. Therapeutic fistuloscopy: an alternative approach in the management of postoperative fistulas. Dig Surg. 2002;19(3):230–235. discussion 236. doi: 10.1159/000064218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lange V, Meyer G, Wenk H, Schildberg F W. Fistuloscopy—an adjuvant technique for sealing gastrointestinal fistulae. Surg Endosc. 1990;4(4):212–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00316795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lamont J P, Hooker G, Espenschied J R, Lichliter W E, Franko E. Closure of proximal colorectal fistulas using fibrin sealant. Am Surg. 2002;68(7):615–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papavramidis S T, Eleftheriadis E E, Papavramidis T S, Kotzampassi K E, Gamvros O G. Endoscopic management of gastrocutaneous fistula after bariatric surgery by using a fibrin sealant. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(2):296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02545-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murakami M, Tono T, Okada K, Yano H, Monden T. Fibrin glue injection method with diluted thrombin for refractory postoperative digestive fistula. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5):715–719. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brady A P, Malone D E, Deignan R W, O'Donovan N, McGrath F P. Fibrin sealant in interventional radiology:a preliminary evaluation. Radiology. 1995;196(2):573–578. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.2.7617880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khairy G E, al-Saigh A, Trincano N S, al-Smayer S, al-Damegh S. Percutaneous obliteration of duodenal fistula. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45(5):342–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lisle D A, Hunter J C, Pollard C W, Borrowdale R C. Percutaneous gelfoam embolization of chronic enterocutaneous fistulas: report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(2):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lomis N N, Miller F J, Loftus T J, Whiting J H, Giuliano A W, Yoon H C. Refractory abdominal-cutaneous fistulas or leaks: percutaneous management with a collagen plug. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(5):588–592. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padillo F J, Regueiro J C, Canis M, et al. Percutaneous management of a high-output duodenal fistula after pancreas transplantation using occluding coiled embolus and fibrin sealant. Transplant Proc. 1999;31(3):1715–1716. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Hoyos A, Villegas O, Sánchez J M, Monroy M A. Endoloops as a therapeutic option in colocutaneous fistula closure. Endoscopy. 2005;37(12):1258. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gronvall J, Gronvall S, Hegedüs V. Ultrasound-guided drainage of fluid-containing masses using angiographic catheterization techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129(6):997–1002. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh B, May K, Coltart I, Moore N R, Cunningham C. The long-term results of percutaneous drainage of diverticular abscess. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90(4):297–301. doi: 10.1308/003588408X285928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.vanSonnenberg E, Ferrucci J T, Jr, Mueller P R, Wittenberg J, Simeone J F. Percutaneous drainage of abscesses and fluid collections: technique, results, and applications. Radiology. 1982;142(1):1–10. doi: 10.1148/radiology.142.1.7053517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaBerge J M, Kerlan R KJ, Jr, Gordon R L, Ring E J. Nonoperative treatment of enteric fistulas: results in 53 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1992;3(2):353–357. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(92)72043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dougherty S H, Simmons R L. The drain-tract sinogram. Guide to the removal of drains and the diagnosis of postoperative abdominal sepsis. Am Surg. 1983;49(9):511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]