Abstract

Purpose:

This paper reviews the origins of the learned professions, the foundational concepts of professionalism, and the common elements within various healer's oaths. It then reveals the development of the Murdoch Chiropractic Graduate Pledge.

Methods:

A committee comprised of three Murdoch academics performed literature searches on the topic of professionalism and healer's oaths and utilized the Quaker consensus process to develop the Murdoch Chiropractic Graduate Pledge.

Results:

The committee in its deliberations utilized over 200 relevant papers and textbooks to formulate the Murdoch Chiropractic Graduate Pledge that was administered to the 2010 Murdoch School of Chiropractic and Sports Science graduates. The School of Chiropractic and Sports Science included professionalism as one of its strategic goals and began the process of curriculum review to align it with the goal of providing a curriculum that recognizes and emphasizes the development of professionalism.

Conclusions:

The reciting of a healer's oath such as the Hippocratic Oath is widely considered to be the first step in a new doctor's career. It is seen as the affirmation that a newly trained health care provider will use his or her newfound knowledge and skill exclusively for the benefit of mankind in an ethical manner. Born from the very meaning of the word profession, the tradition of recitation of a healer's oath is resurgent in health care. It is important for health care instructors to understand that the curriculum must be such that it contributes positively to the students' professional development.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Education, Ethical Oaths, Professional

Introduction

The recitation of a healer's oath such as the Hippocratic Oath is widely considered to be the first step in a new doctor's career; it is seen as the affirmation that a newly trained health care provider will use his or her newfound knowledge and skill exclusively for the benefit of mankind. Although the best known, Hippocrates' statement is certainly not the only such pledge taken by new graduates, and many pre-date the Greek one significantly. This tradition continues today at commencement ceremonies for healers of all types and encompasses the concepts of professionalism and ethical behavior for those at the beginning of their career as a healer.

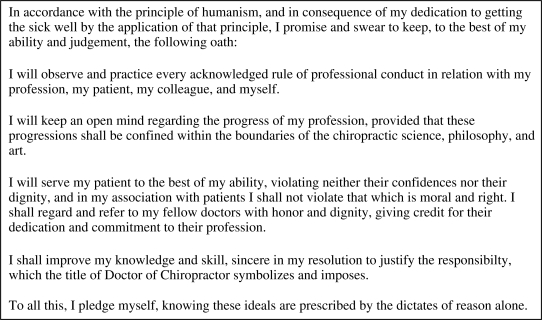

The Murdoch University School of Chiropractic, hereafter referred to as the School, graduated its first cohort in 2006. The graduating class of 2008 swore a “Chiropractic Oath” (Fig. 1), which, while it incorporated all that a professional oath should, was a hybrid of existing chiropractic oaths, prepared at short notice by an academic member of staff and thus was not entirely tailored to the School's needs.

Figure 1.

The 2008 Murdoch Graduate Oath.

In 2009 the School Board resolved to research and develop a new graduation “oath.” The School's reasoning for the new oath was a desire to have the graduating chiropractor reflect on their professional academic career and declare a commitment to the graduate attributes that are embedded throughout the 5-year program. An additional reason for reviewing the graduation oath was to be sure that it incorporated changes in modern thinking and science, thereby avoiding cultural lag or “failure of societal groups to keep pace with advances in science or changes in society.”1 In recognition of the desirability to make an oath “pragmatically modern,”2 other health care professions established this precedent by reviewing their professional oath, in one instance after maintaining the same text for 300 years, and in other instances the oath is revised annually by students.3–7 The terms of reference of the newly formed Murdoch Oath Committee (MOC) was to develop a Murdoch graduate oath that embodied the spirit of the professional oath and at the same time embraced the School's ethos of evidence-based, patient-centered care and social justice.

The purpose of this paper is to raise awareness within the chiropractic literature of this topic by examining the evolution of the professions and the role of the professional oath therein, and to outline the development of the Murdoch Chiropractic Graduate Pledge based on this foundation. This paper recounts the MOC's research and deliberations.

Methods

The MOC was constituted with three academics from within the School of Chiropractic and Sports Science and chose to operate using the Quaker consensus decision process. The Quaker process is an effective alternative to a majority rule model. It strives for unity rather than unanimity by encouraging all members of a group to be heard and to share information until the sense of the group is clear. This allows for and facilitates the dissenters' voice, thereby encouraging diversity of thought and guaranteeing a genuine group decision.8, 9 In undertaking its task the MOC researched the concept of professionalism and the origins of the professions, as well as the origins and content of the professional oath. Once the MOC had a clear appreciation for this background information, it undertook to develop a graduate chiropractic oath for the School's consideration.

Two committee members undertook independent literature searches using the following keywords: profession, professionalism, education, teaching, oath, pledge, promise, chiropractic, medical, and healer. The following databases were searched using the above keywords: Mantis, Index to Chiropractic Literature, CINAHL, Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science (ISI), and Murdoch University Library Catalogue. Other sources, such as the authors' personal libraries, were also searched for pertinent information.

The authors each compiled a database of relevant references using EndNote (Thomson Reuters, Carlsbad, California). These were then merged into a single database. A total of 210 relevant papers and textbooks were identified. The papers were then printed, read, and analyzed. The MOC then convened to consider its task.

Results

Deliberations of the MOC: An Oath, Promise, Pledge, or a Declaration?

Before developing the Murdoch graduate oath, the MOC gave consideration to the question: what differentiates an oath from a promise, a pledge, and a declaration? An oath is defined as a solemn, usually formal, calling upon a deity to witness to the truth of what one says or to witness that one sincerely intends to do what one says.10 According to Sulmasy:

Oaths are generally characterized by their greater moral weight compared with promises, their public character, their validation by transcendent appeal, the involvement of the personhood of the swearer, the prescription of consequences for failure to uphold their contents, the generality of the scope of their contents, the prolonged time frame of the commitment, the fact that their moral force remains binding in spite of failures on the part of those to whom the swearer makes the commitment, and the fact that interpersonal fidelity is the moral hallmark of the commitment of the swearer.11

A promise, however, is a verbal commitment by one person to another agreeing to do (or not to do) something in the future,12 whereas a declaration is a statement made by a party to a legal transaction usually not under oath.13 A pledge is a solemn binding promise or agreement to do or to refrain from doing something.14

It is important to recognize that by whatever name, the healer's oath carries with it a moral obligation on behalf of the speaker.15, 16 With an appreciation for this etymological question, the MOC set about the task of revising the 2008 Murdoch Graduate Oath (Fig. 1).

The first consideration surrounded the phrase “In accordance with the principle of humanism.” While certainly those principles are held within the ideals expressed in the oath and even within the concept behind becoming a health care practitioner,17, 18 it was suggested that stating this overtly in the oath could alienate those segments of the population who believe in a supreme being or beings. Further it was felt that some people could interpret the phrase as meaning that they were becoming adherents to a certain “philosophy” (humanism) in a dogmatic fashion. The phrase was dropped in favor of interweaving the concepts of humanism into the Pledge.

In recognition of this, the MOC determined that a statement embracing the Humanist principle that “all human beings are entitled to inalienable human rights such as those enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights'′19 would be appropriate within the Pledge. The principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, justice, and respect for patient autonomy are the fundamental aspects of bioethics.20 However, the graduating chiropractor needs to remember that beneficence has three important constraints:

The need to respect the autonomy of those whom he or she intends to help, especially to find out what it is they want in the way of help.

The need to ensure that the help that he or she renders is not bought at too high a price.

The need to consider the wants, needs, and rights of others.21

Benevolence is defined as “the character trait or virtue of being disposed to act for the benefit of others” while a “principle of beneficence refers to a moral obligation to act for the benefit of others'′22 and justice is synonymous with fairness and represents the moral obligation to act on the basis of fair judgment between competing claims.23 In chiropractic, much as in other health care professions, the practitioner is often confronted by opposing moral orders. One based on the primacy of the patient's needs, and the other the primacy of the self and the marketplace.24 While this may be seen by some as a conflict arising from fiduciary duty,25 based on their commitment to treat all patients equally and without prejudice, as well as their pledge to benevolence, it is expected that the graduate will, within reason, choose to place the needs of the patient above the needs of the self.

The MOC recognized that any list of groups dividing and defining people by race, religion, and so forth cannot be complete, and so the decision was taken to strike all divisions from reference in the Oath. A phrase was crafted stating that all people (ie, not just patients) would be approached with equal benevolence, because true health care professionals must never show prejudice against any individual at any time, not just during office hours.

The next debate was over the phrase “moral and right” in the fourth paragraph of the 2008 Graduate Oath. The MOC recognized that ethics, morality, and all social norms are arbitrary, simply an agreed-upon set of customs adopted by a group or culture.26 The MOC accepted Harris′27 construct of culture: a learned repertoire of thoughts and actions exhibited by members of a social group that is transmitted independently from genetic transmission from one generation to the next. Further, there may exist highly differentiated subcommunities or subcultures within a group that is held together by occupational title, and these subcultures may be in conflict with one another.28 This is most certainly the case within chiropractic. For example, there remains within chiropractic a school of thought that either overtly or covertly adheres to the 19th-century Palmerian ideology of “the nerve is supreme,” and that “bone out of place/foot on hose” theory. Some chiropractors see the highest morality in ignoring patients' physical symptoms, x-raying all patients, or giving adjustments only to the upper cervical spine,29 even though the best available scientific evidence suggests that there is no safe or threshold level of radiation exposure,30 and the utility of postural and biomechanical evaluation of x-rays is questionable.31, 32 These views are diametrically opposed to those of chiropractors who ascribe to 21st-century evidence-based practice and adhere to internationally recognized standards of health care.33–35 Furthermore, chiropractic has a wide and varying scope of practice throughout the various countries and localities in which it is practiced and taught.36 In light of these considerations and in recognition of the underpinning principles of the healer's oath, the MOC determined that specifics regarding behavior would serve the oath better than generalities, such as “moral and right.”

Independent and lifelong learning is not only one of Murdoch University's graduate attributes,37 it is well accepted within the learned professions that the graduate cannot rely solely on the knowledge and skills gained during their undergraduate training to see them through their career in professional practice.38 Indeed, lifelong learning fits into the professional's fiduciary duties. Given this, plus the established fact that excellence is one of the attributes of a profession, it is therefore fitting to have the graduates affirm their dedication to maintain and improve their skill and knowledge base in order to best address their patients' needs. The MOC chose carefully the words to convey this message: Pledge takers affirm to judiciously improve their knowledge and skill, a task, which clearly requires commitment. This commitment carries with it a sense of obligation to act in such a way that best meets the needs of the patient. In addition, graduates affirm that they remain open to the developments within their profession. Openness requires that they are willing to hear the opinions of others, without preconception. The concept of openness was extended beyond the chiropractic profession by the addition of the phrase: I will regard and refer to my fellow doctors with honour and respect, which in this context, a doctor may be taken to mean fellow healers.

Next, the phrase “helping the sick get well” was debated and was determined to be too illness oriented and was therefore excluded. Finally, the last sentence of the 2008 Oath was modified to include “science and reason” because it was felt that rational and reasonable health care must necessarily be in the dominion of the scientific method, specifically observation, logic, and conscious consideration.

Although oaths have traditionally been sworn, swearing has a strong religious connotation,39 and not all healers, including chiropractors, are deists or theists. A recent movement has worked toward being more inclusive of nontheists40 and some oaths have been modified to include the option to affirm, rather than swear. Thus, on the basis of the aforementioned definitions, and in recognition of the humanistic nature of the Murdoch chiropractic program, the MOC opted to use the word pledge rather than oath when referring to the document it produced and recommended that those taking the pledge “affirmed” their willingness to abide by the dictates of the pledge. The final pledge is seen in Figure 2. To accompany the Pledge, the MOC also developed a Preamble which summarizes the origins of the learned professions and the healer's oath. The reasoning behind this was to remind readers of the meaning behind the words of the Pledge.

Figure 2.

The 2010 Murdoch Chiropractic Graduate Pledge.

The Pledge was unanimously endorsed by the School Board at its November 2009 meeting, and it was subsequently administered to the 2009 graduating students. In addition, an invitation was extended to all chiropractors to attend the ceremony and, should they so desire, retake their healer's oath, a practice, which also occurs in medicine.41

Discussion

What became apparent from the outset was that while the subject of professionalism occupies a significant place in the medical literature with more than 1500 publications over a 6-year period between 2002 and 200842 there is a noticeable dearth within the chiropractic literature. Searches of Mantis, Index to Chiropractic Literature, CINAHL, Scopus, and PubMed, using search terms “chiropractic education and professionalism,” returned only four hits.

Wear and Kuczewski43 argue that it is important to establish a theoretical framework in order to understand the physician's responsibility. In order to truly understand this, it was necessary for the MOC to examine the origins of the professions.

Craft Guilds to the Learned Professions: A Brief History

The earliest recorded use of the word profession in relation to medicine was by Scribonius Largus, a physician in the court of the Roman Emperor Claudius in 47 CE (Common Era). Scribonius referred to the “profession” of medicine, which he defined as a commitment to the relief of suffering.44 The use of the word profession to describe or define an occupational group would not come about until much later.

Throughout Europe in the late middle ages, guilds were the principal way of structuring work. A guild was a social group established by workers with like interest, namely their trade or pursuit. A guild's power arose from that guild's ability to control four key aspects of its commerce: membership in the guild, activity within the guild, the market for its goods or services, and its relationship with the state or jurisdiction.45

Guilds were typically strong, self-governing fraternities with rules governing entry, training, and behavior, and they were responsible for enforcing their behavioral rules. Principally due to the growth of “free-market” capitalism, the craft guilds went into decline by the late 1700s.45

Developing in the same era and surviving the demise of the craft guilds were the universities or scholars' guilds. These were guilds of masters and students. From these early universities emerged what became known as the Learned Professions: Theology, Law (canon and civil or common) and Medicine.45

The word profession is derived from the Latin professionem, meaning public declaration or oath. Following extensive training encompassing specialized and restricted knowledge, the emergent professional made a public declaration of adherence to ethical standards, which invariably included trustworthiness, practitioner–client confidentiality, truthfulness, the striving to be an expert in one's calling, and practicing for the benefit of the client above all.46 In medicine the practice of publicly declaring an oath can be traced back centuries.6, 47 Members of the learned professions formed professional guilds and these were similar in function to the craft guilds in that they were strong, self-governing fraternities with entry by examination and expert training with behaviors prescribed by a code of ethics, the enforcement of which remained the domain of the profession.45, 48

There is agreement among analysts that there are four foundational elements in every profession: monopoly, altruism, autonomy, and excellence.45, 49, 50 Because of the specialized knowledge of the profession, they are given a virtual monopoly over its dissemination and application. Altruism underpins the use of the knowledge in the service of individual clients and society. The specialized nature of the knowledge plus a commitment to altruism forms the basis for society's granting autonomy to the profession for establishing and maintaining the highest standards of practice for their calling. There is societal expectation that the professionals will strive for excellence by ongoing expansion of their knowledge base through research to thereby ensure the highest standards of care.51 These four elements form the basis for what has become known as the “social contract” in health care involving the profession, society, government, and other agencies.46, 50, 51 The social contract has both written (legislative) and de facto moral aspects.24

Stern et al52 suggest that there are four pillars to professionalism: humanism, accountability, altruism, and excellence, while DeRosa suggests that “a profession in the best sense of the term is a moral undertaking.”53 When practiced, humanism in medicine promotes compassionate, empathetic relationships with patients and other caregivers.54, 55 It also envisions behaviors and attitudes that are sensitive to the values and culture of others while respecting their autonomy.56 It has been suggested that even though the terms professionalism and humanism each have their own definition, both are inseparably interwoven into the practice and art of “medicine.”57 Cohen57 proposes that there be a distinction between professionalism and humanism by arguing that professionalism is associated with a set of actions and behaviors; humanism is connected to a set of beliefs that positively influence professionalism. According to Cohen, “Humanism is the passion that animates authentic professionalism”57 and is becoming even more relevant in the pluralistic postmodern age in which we live.58 Indeed, professionalism and humanism share common values such that one enriches the other.55 This connection has been recognized as forming an integral part of modern health care52, 54, 59 with the moral aspects of the social contract being embodied in humanism.

The problem arises, however, that over time, occupational groups other than the learned professions have claimed “professional” status by dint of training, knowledge base, and licensing, thus leading to a blurring of the meaning of the word professional.48 As Howsam et al point out, “opting to use the name does not, however, insure that the status of profession will thereby be achieved.”60 Etzioni61 suggested that the title profession be reserved for those dealing with matters of life and death and semiprofession or emergent profession be used for the others. Another effort to clarify the situation came from Elliott's62 suggestion that the term “status professions” be used for the learned professions to differentiate them from the more recent “occupational professions,” which may have some, but not all, of the elements of a status profession. Perhaps more utilitarian is McGill University's differentiation, which is presented to 1st-year medical students and is reinforced throughout their education. McGill University63 differentiates between the characteristics of a “healer” and those of a “professional” (Table 1). While there may be some scope for arguing by some occupational professions for elevation to “status,” there is a fundamental difference, one that goes to the very core of the healer professional. Because of the “extreme dependence” of the client upon the healer,64 there exists a fiduciary relationship between the doctor and client.65–67 According to Sharpe, “the fiduciary relationship is based on dependence, reliance, discretionary authority and trust.”68 The fiduciary (doctor) has three separate duties toward the “fiducie,” a word coined by Rodwint65 to describe the person whose good is held in trust by the fiduciary:

A duty of loyalty: Doctors must place the interests of their clients above their own interests.

A duty of care: Doctors must have the necessary knowledge to perform their duty.

A duty of disclosure: Doctors must disclose limitations, conflicts of interest, and barriers to performing their duties.67

It is well established that chiropractors fulfill the requirements of a healer professional and as such are bound in a fiduciary relationship with their patients.36, 69–72 It follows, therefore, that it is appropriate for graduating chiropractors to profess their commitment and obligations on entering their profession.

Table 1.

Professional/healer attributes

| Attribute | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| The Healer | Caring and compassion | A sympathetic consciousness of another's distress together with a desire to alleviate it. Insight: self-awareness; the ability to recognize and understand one's actions, motivations and emotions. |

| Openness | Willingness to hear, accept, and deal with the views of others without reserve or pretence. | |

| Respect for the healing function | The ability to recognize, elicit, and foster the power to heal inherent in each patient. | |

| Respect for patient dignity and autonomy | The commitment to respect and ensure subjective well-being and sense of worth in others and recognize the patient's personal freedom of choice and right to participate fully in his/her care. | |

| Presence | To be fully present for a patient without distraction and to fully support and accompany the patient throughout care. | |

| The Professional | Responsibility to the profession | The commitment to maintain the integrity of the moral and collegial nature of the profession and to be accountable for one's conduct to the profession. |

| Self-regulation | The privilege of setting standards; being accountable for one's actions and conduct in medical practice and for the conduct of one's colleagues. | |

| Responsibility to society | The obligation to use one's expertise for, and to be accountable to, society for those actions, both personal and of the profession, which relate to the public good. | |

| Both the Healer and the Professional | Teamwork | The ability to recognize and respect the expertise of others and work with them in the patient's best interest. |

| Competence | To master and keep current the knowledge and skills relevant to medical practice. | |

| Commitment | Being obligated or emotionally impelled to act in the best interest of the patient; a pledge given by way of the Hippocratic Oath or its modern equivalent. | |

| Confidentiality | To not divulge patient information without just cause. | |

| Autonomy | The physician's freedom to make independent decisions in the best interest of the patients and for the good of society. | |

| Altruism | The unselfish regard for, or devotion to, the welfare of others; placing the needs of the patient before one's self-interest. | |

| Integrity and honesty | Firm adherence to a code of moral values; incorruptibility. | |

| Morality and ethics | To act for the public good; conformity to the ideals of right human conduct in dealings with patients, colleagues, and society. | |

Used with permission from Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Teaching medical professionalism. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Why an Oath in 2010?

For many years the common belief was that the transformation of what we will call healers-in-training and specifically the acquisition of professional values by healers-in-training for the most part occurred by a type of osmotic enculturation from teachers and mentors.73–75 More recently there has been a realization among medical educators that professionalism must not only form an integral part of the hidden curriculum,76–81 but that it must be taught and assessed within the formal curriculum.79, 82–88 It is noteworthy that unless the hidden curriculum is aligned with professionalism, an institution's effort to promote professional behavior amongst students may be undermined.77, 89, 90 This has been recognized by some medical faculties which have implemented a formal campuswide project to create a culture of professionalism, or perhaps more explicitly what Marcus calls “altruistic humanism” both within the formal curriculum as well as the hidden curriculum.18, 91 Further, chiropractic students hold professionalism in high regard, as do medical students and practicing chiropractors,92–95 which would lend support to the position that professionalism should be formally taught and assessed. European and American medical schools have recognized a need to develop a sense of professionalism among graduating physicians,24, 79, 82, 83 resulting in a number of medical organizations developing a “Charter on Medical Professionalism”96 that is based on the principles of primacy of patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice.97

While the process of the healer's education is long,28, 98 there is a final step that historically has been recognized as the culmination of the healer's training. This is the swearing or declaring of an oath.

The recital of a healer's oath has three broad purposes. The first is to create a professional obligation to voluntarily practice according to the ethics articulated in the text,16, 99 the assumption being that such a declaration may serve as a “code of ethics” offering practitioners moral guidance based on the ageless virtues of honesty, sacrifice, and selflessness.100 It is important to realize that an ethical code does not provide answers to all ethical questions; rather the code only functions as a guide to the practitioner by describing the ethical environment for the delivery of health care.101

While obviously related to the more personal affirmation of professional conduct, the second purpose is to make a statement to the general public about the ethics of the profession as a whole. Finally, the reciting of the oath is recognized as an avowal of tradition in which the oath takers are aware of and affirm a tradition of social and professional responsibility.102

Even though oaths do not guarantee ethical behavior and do not impose a legal obligation on the taker, there has been an obvious resurgence in interest in oaths.3, 4, 56, 99, 103–105 In 1928 fewer than 25% of medical schools in the United States and Canada required graduating students to take an oath,5 whereas in 2004 almost every medical school in the United States administered a professional oath.41 Figures from 2002 indicate that 58% of medical schools in Australia and New Zealand required graduating medical students to make a declaration of ethical commitment.106 This percentage had increased to 76 in 2006.7 There are several reasons for these increases, not the least of which is a general erosion of public confidence in medicine.107, 108 which has led to the recognized need to “strengthen and extend the kind of fiduciary morality that has long been part of the ethos'′109 of health care professionals and the re-establishment of the social contract.28, 110 This appears to have resulted in a renewed interest in oaths because affirmation may strengthen a doctor's resolve to behave in an ethical and professional manner.7, 111

Origins of the Healer's Oath

The Hippocratic Oath is likely the most widely recognized healer's oath. While the Hippocratic Oath has been used in medical graduation ceremonies since 1508,41 it was not the first such oath. The Hippocratic Oath requires a doctor entering the profession to swear upon a number of healing gods that he or she will uphold a number of professional ethical standards.

Although little is known regarding the original authorship or who first used it, it appears to have been more strongly influenced by followers of Pythagoras than Hippocrates and it is believed to have been written in the 4th century BCE (Before the Common Era). Many cultures have rewritten the Hippocratic Oath to suit their values but, contrary to popular belief, the Hippocratic Oath is not the healer's oath used by most modern medical schools.112

Hindu physicians took the Oath of the Hindu Physician, also known as the Vaidya's Oath. It is dated from the 15th century BCE and required physicians not to eat meat, drink alcohol, or commit adultery. Similar to the Hippocratic Oath, the Vaidya's Oath beseeched physicians not to harm their patients and to be exclusively devoted to their care.113

The Seventeen Rules of Enjuin are a code of conduct developed for students of the Japanese Ri-shu school of medicine in the 16th century CE (Common Era). The rules are similar to the Hippocratic Oath in that they stress the rights of the physicians' teachers, require the physician to respect the patient's confidentiality, and prohibit both euthanasia and abortion. They also emphasized that physicians should love their patients and that they should work together as a partnership.114

The Prayer of Moses Maimonides is a prayer presumed to have been written by the 12th-century physician-philosopher Moses Maimonides. Like the Hippocratic Oath, new medical graduates often recite the prayer of Maimonides. Recent scholars have questioned who penned the prayer, suggesting that rather than Maimonides, it may have been written by Marcus Herz, a German physician. This notwithstanding, the prayer first appeared in print in 1793, which may coincide with its authorship. The prayer entreated “Almighty God” to guide physicians during their ministrations in upholding ethical standards similar to those expressed in the Hippocratic Oath.115

Nurses have been using the Nightingale Pledge, an adaptation of the Hippocratic Oath, since 1893. It reads:

I solemnly pledge myself before God and in the presence of this assembly, to pass my life in purity and to practice my profession faithfully. I will abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous, and will not take or knowingly administer any harmful drug. I will do all in my power to maintain and elevate the standard of my profession, and will hold in confidence all personal matters committed to my keeping and all family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice of my calling. With loyalty will I endeavor to aid the physician, in his work, and devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care.116

In 1948, the World Medical Association, an association of national medical associations, adopted the Declaration of Geneva–Physician's Oath. This appears to be a response to the atrocities committed by medical practitioners in Nazi Germany during World War II. This oath, which was amended by the 22nd World Medical Assembly in Sydney, Australia, in August 1968, requires the physician to “not use [his] medical knowledge contrary to the laws of humanity.”2, 117 In an effort to modernize the Tufts Medical College oath, in 1964 Lous Lasagna, then academic dean, developed his own personal oath that is still used today in many medical schools.103

Within the chiropractic profession, the administering of an oath by new chiropractors entering the profession dates back to 1911. The various chiropractic oaths in use have a commonality with those noted below118, 119 and are intended to serve as principles underpinning and guiding the practitioner's day-to-day activities.120

In recognition of the commonalities between the various healer's oaths as well as the merits in unifying the healing arts for the benefit of the patient, suggestions have been made that the crafting of a panprofessional ethical code would be an exercise worth pursuing.99

Common Elements Among Healer's Oaths

Close scrutiny of healer's oaths reveals the common elements of medical ethics, professional standards, and legal and societal standards. These elements include

Serving humanity to the best of the healer's training and ability,

Refraining from intentionally harming a patient,

Placing the interests of the patient above those of the healer's or other interests such as financial gain,

Accepting patients in a nondiscriminatory manner,

Respecting patient confidentiality,

Continually improving the healer's knowledge and skill level,

Respecting one's profession, and

A willingness to impart the knowledge of the healing art to others who are formally studying the art.

In addition, modern oaths include elements relating to respecting patient autonomy, avoiding bias, and advancing a just society.3, 119, 121, 122

Conclusion

The transformation of lay students into practicing professionals is fundamentally the same in all professions: the assimilation of the profession's “culture” and principles of practice. Within health care this involves a formal curriculum designed to include technical standards consisting of recognized competencies set by accreditation bodies. These may be competencies common to all healing professions (eg, history taking, record keeping, and physical examination). There are also essential attributes that a health care professional should possess: altruism, compassion, and respect for client autonomy. These are, in a sense, the embodiment of the professional's fiduciary duties of loyalty, care, and disclosure. While traditionally the ethical and moral transformation from student to professional has been considered a passive process, more recently there has been recognition that all aspects of professional development must form part of both the formal and hidden curriculum.

A committee of Murdoch academics reviewed the origins of the learned professions and the role that the healer's oath plays in professional development. The Murdoch Oath Committee followed a consensus process formulated by the Quakers, a religious organization also known as The Religious Society of Friends, and formulated a humanistic pledge that incorporates the essential elements of a healer's oath, reminds graduating students and others of their obligations as a healer and professional, and will serve as a guidepost to chiropractic graduates from the Murdoch School of Chiropractic and Sports Science.

On the surface, the task of rewording the 2008 Graduate Oath appeared to be a simple and straightforward task. On closer examination it became apparent to the MOC and ultimately the School that the graduate oath or pledge is the pronouncement of the graduating student's acceptance of his or her contractual commitment to society. In reviewing literature on professionalism within medical education, the MOC recognized and the School accepted that there is a need for the School to reflect upon its curricula, formal and hidden, and to bring it into alignment with the School's stated educational goals including, but not limited to, providing a curriculum that recognizes and emphasizes the development of professionalism.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

J. Keith Simpson, Murdoch University School of Chiropractic and Sports Science.

Barrett Losco, Murdoch University School of Chiropractic and Sports Science.

Kenneth J. Young, Murdoch University School of Chiropractic and Sports Science.

References

- 1.Robin E, McCauley R. Cultural lag and the Hippocratic Oath. Lancet. 1995;345(8962):1422–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith L. A brief history of medicine's Hippocratic Oath, or how times have changed. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowes R. Is the Hippocratic Oath still relevant? Med Econ. 1995;72(11):197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theunissen C. It's about time we had a professional oath in psychology. Austral Psychol. 2008;43(1):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orr R, Pang N, Pellegrino E, Siegler M. Use of the Hippocratic Oath: a review of twentieth century practice and a content analysis of oaths administered in medical schools in the U.S. and Canada in 1993. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8(4):377–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watt G. The New Glasgow Medical and Dental Graduation Declaration. Scottish Med J. 2006;50(1):27–29. doi: 10.1258/RSMSMJ.51.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macneill P, May A, Dowton S. An opportunity to reinforce ethical values: declarations made by graduating medical students in Australia and New Zealand. Intern Med J. 2009;39(2):83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis M. In the manner of Friends: learnings from Quaker practice for organizational renewal. J Organ Change Manage. 1994;7(1):42–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sager K, Gastil J. Reaching consensus on consensus: a study of the relationships between individual decision-making styles and use of the consensus decision rule. Commun Q. 1999;47(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dictionary.com. “Oath.”. Available at: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/oath. Accessed Feb. 15, 2010. Unabridged.

- 11.Sulmasy D. What is an oath and why should a physician swear one? Theor Med Bioethics. 1999;20:329–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1009968512510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dictionary.com. “Promise.”. Available at: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/promise. Accessed Feb. 15, 2010. Unabridged.

- 13.Dictionary.com. “Declaration.”. Available at: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/declaration. Accessed Feb. 15, 2010. Unabridged.

- 14.Dictionary.com. “Pledge.”. Available at: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pledge. Accessed Feb. 15, 2010. Unabridged.

- 15.Gillon R. Medical oaths, declarations, and codes. Br Med J. 1985;290:1194–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6476.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sritharan K, Russell G, Fritz Z, et al. Medical oaths and declarations: a declaration marks an explicit commitment to ethical behaviour. BMJ. 2001;323(7327):1440–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabow MW, Wrubel J, Remen RN. Promise of professionalism: personal mission statements among a national cohort of medical students. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):336–42. doi: 10.1370/afm.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus E. Empathy, humanism, and the professionalization process of medical education. Acad Med. 1999;74:1211–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunasekara V. The core principles of secular humanism: twelve fundamental principles stated and examined. Available at: http://uqconnect.net/slsoc/manussa/coreprin.htm - ch2. Accessed Feb. 28, 2010.

- 20.Rancich A, Pèrez M, Morales C, Gelpi R. Beneficence, justice, and lifelong learning expressed in medical oaths. J Contin Educ Health Profess. 2005;25(3):211–20. doi: 10.1002/chp.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillon R. Beneficence: doing good for others. Br Med J. 1985;291(6487):44–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6487.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillon R. Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ. 1994;309(6948):184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6948.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellegrino E. The medical profession as a moral community. Bull NY Acad Med. 1990;66:221–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart D. Conflict in fiduciary duty involving health care error reporting. Med Surg Nurs. 2002;11(4):187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haidt J, Koller S, Dias M. Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(4):613–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris M. Cultural materialism: the struggle for a science of culture. Updated edition. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freidson E. Professionalism: the third logic. On the practice of knowledge. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Federation of Straight Chiropractics and Organizations. Vertebral subluxation: nothing more–nothing less. Available at: http://www.straightchiropractic.com/. Accessed March 4, 2010.

- 30.Monson R. Beir VII: health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. Chairman. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas M, Taylor JAM, Gillette RG. The routine use of radiographic spinal displacement analysis: a dissent. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1999;22(4):254–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(99)70053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ernst E. Chiropractors' use of x-rays. Br J Radiol. 1998;71(843):249–51. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.843.9616232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keating JC., Jr Chiropractic: science and antiscience and pseudoscience side by side. Skeptical Inquirer. 1997;(July/Aug):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keating JC, Jr, Charlton KH, Grod JP, Perle SM, Sikorski D, Winterstein JF. Subluxation: dogma or science? Chiropr Osteop. 2005:13–17. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feise R. Evidence-based chiropractic: the responsibility of our profession. J Am Chiropr Assoc. 2001:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapman-Smith D. The chiropractic profession. its education, practice, research and future directions. DeMoines, IA: NCMIC Group Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murdoch University. The nine attributes of a Murdoch graduate and the subattributes. Available at: http://www.tlc.murdoch.edu.au/gradatt/attributes.html. Accessed Feb. 28, 2010.

- 38.Bolton J, Humphreys B. New approaches to continuing education in chiropractic. Br J Chiropr. 2003;1(2):12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graham D. Revisiting Hippocrates: does an oath really matter? JAMA. 2000;284(22):2841–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swick H. Professionalism and humanism: beyond the academic health centre. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1022–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181575dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markel H. “I Swear by Apollo” —on taking the Hippocratic Oath. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2026–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphrey HJ. Medical professionalism: introduction. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):491–4. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wear D, Kuczewski M. The professionalism movement: can we pause? Am J Bioethics. 2004;4(2):1–10. doi: 10.1162/152651604323097600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellegrino E. Professionalism, profession and the virtues of the good physician. Mount Sinai J Med. 2002;69(6):378–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krause E. Death of the guilds. Professions, states, and the advance of capitalism, 1930 to the present. New Haven CT, and London: Yale University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Expectations and obligations: professionalism and medicine's social contract with society. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):579–98. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodruff J, Angelos P, Valaitis S. Medical professionalism. One size fits all? Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):525–34. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abbott A. The system of professions. An essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago IL, and London: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodruff JN, Angelos P, Valaitis S. Medical professionalism: one size fits all? Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):525–34. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starr P. The social transformation of American medicine. The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cruess R, Cruess S, Johnston S. Professionalism and medicine's social contract. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82(8):1189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stern DT, Cohen JJ, Bruder A, Packer B, Sole A. Teaching humanism (medical students training) Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):495–507. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeRosa G. Professionalism and virtues. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:28–33. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224025.03658.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wear D, Bickel J. Educating for professionalism. Creating a culture of humanism in medical education. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swick HM. Viewpoint: professionalism and humanism beyond the academic health center. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1022–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181575dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loudon I. The Hippocratic oath. Br J Med. 1994;309(6951):414a. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6951.414a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen JJ. Viewpoint: Linking professionalism to humanism: what it means, why it matters. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1029–32. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285307.17430.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trotter G. Bioethics and healthcare reform: a Whig response to weak consensus. Cambridge Q Healthcare Ethics. 2002;11(01):37–51. doi: 10.1017/s096318010210106x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markakis KM, Beckman HB, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The path of professionalism: cultivating humanistic values and attitudes in residency training. Acad Med. 2000;75(2):141–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howsam R, Corrigan D, Denemark G, Nash R. Educating a profession. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Etzioni A. The semi-professions and their organization: teachers, nurses, social workers. New York: The Free Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elliott P. The sociology of the professions. London: McMillan; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cruess R. Teaching professionalism. Theory, principles, and practices. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:177–85. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229274.28452.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ross E. The making of the professions. Int J Ethics. 1916;27(1):67–81. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodwint A. Stains in the fiduciary metaphor: divided physician loyalties and obligations in a changing health care system. Am J Law Med. 1995;XXI(2&3):241–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosen K. Meador lecture series 2006–2006: fiduciaries. Alabama Law J. 2007;58(5):1041–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glannon W, Ross L. Are doctors altruistic? J Med Ethics. 2002;28:68–69. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sharpe VA. Why “do no harm”? Theor Med Bioethics. 1997;18(1):197–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1005757606106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chapman-Smith D. The chiropractic profession. Its education, practice, research and future directions. West Des Moines, IA: NCMIC Group Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wardwell W. Chiropractic: history and evolution of a new profession. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kinsinger S. Set and setting: professionalism defined. J Chiropr Humanities. 2005;12:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meeker W, Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:216–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cruess R, Cruess S. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teacher. 2006;28(3):205–8. doi: 10.1080/01421590600643653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Handelsman M. Problems with ethics training by “osmosis.”. Profess Psychol Res Pract. 1986;17(4):371–2. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coulehan J. Today's professionalism: engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):892–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hafferty F, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.West C, Chur-Hansen A. Ethical enculturation: the informal and hidden ethics curricula at an Australian medical school. Focus on Health Professional Situation: A Multi-Disciplinary Journal. 2004;6(1):85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brainard AH, Brislen HC. Viewpoint: Learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1010–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Swick H, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb M. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 1999;282(9):830–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hafferty F. Professionalism and medical education's hidden curriculum. In: Wear D, Bickel J, editors. Educating for professionalism creating a culture of humanism in medical education. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: qualitative study of medical students' perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329:770–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stephenson A, Higgs R, Sugarman J. Teaching professional development in medical schools. Lancet. 2001;357:867–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04201-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cruess S, Cruess R. Professionalism must be taught. BMJ. 1997;315:1674–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7123.1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cruess S, Johnston S, Cruess R. Professionalism for medicine: opportunities and obligations. Med J Aust. 2002;177(4):208–11. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Doukas D. Returning to professionalism: the re-emergence of medicine's art. Am J Bioethics. 2004;4(2):18–19. doi: 10.1162/152651604323097664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kinsinger S. Advancing the philosophy of chiropractic: advocating virtue. J Chiropr Humanities. 2004;11:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kinsinger S. Teaching professionalism to students. J Chiropr Educ. 2003;17(1):63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 88.McNair R. The case for educating health care students in professionalism as the core content of interprofessional education. Med Educ. 2005;39:456–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brater DC. Viewpoint: Infusing professionalism into a school of medicine: perspectives from the dean. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1094–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181575f89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suchman A, Williamson R, Litzelman D, Frankel R, Mossbarger D, Inui T. Toward an informal curriculum that teaches professionalism. Transforming the social environment of a medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(Part 2):501. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smith KL, Saavedra R, Raeke JL, O'Donell AA. The journey to creating a campus-wide culture of professionalism. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1015–21. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318157633e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wrangler M. Usefulness of CanMEDS competencies for chiropractic graduate education in Europe. J Chiropr Educ. 2009;23(2):123–33. doi: 10.7899/1042-5055-23.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leo T, Eagen K. Professionalism education: the medical student response. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):508–16. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Francis CK. Professionalism and the medical student. Lancet. 2004;364(9446):1647–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hafferty F. What medical students know about professionalism. Mount Sinai J Med. 2002;69(6):385–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jotkowitz A, Glick S. The physician charter on medical professionalism: a Jewish ethical perspective. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(7):404–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.009423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.ABIM Foundation A, ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Freidson E. Professional powers. A study of the institutionalization of formal knowledge. Chicago IL, and London: University of Chicago Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hurwitz B, Richardson R. Swearing to care: the resurgence in medical oaths. BMJ. 1997;315:1671–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7123.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Linker B. The business of ethics: gender, medicine, and the professional codification of the American Physiotherapy Association, 1918–1935. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2005;60(3):320–54. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jri043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Limentani A. An ethical code for everybody in health care. The role and limitations of such a code need to be recognized. BMJ. 1998;316(7142):1458. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7142.1458a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith D. The Hippocratic Oath and modern medicine. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1996;51(4):484–500. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/51.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Meffert J. “I swear!” Physician oaths and their current relevance. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(4):411–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Millard P. Resurgence of interest in medical oaths and codes of conduct. BMJ. 1998;316:1749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rampe K. Do we need the Hippocratic oath today? The classic version is outdated, but we still need an ethical declaration on graduation. Student BMJ. 2009;17:b1032. [Google Scholar]

- 106.McNeill P, Dowton S. Declarations made by graduating medical students in Australia and New Zealand. Med J Australia. 2002;176(3):123–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sullivan W. Medicine under threat: professionalism and professional identity. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162(5):673–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Freidson E. The reorganization of the professions by regulation. Law Hum Behav. 1983;7(2/3):279–90. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Arnold L. Assessing professional behaviour: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77:502–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Freidson E. Professionalism reborn. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 111.British Medical Association. Medicine betrayed: the participation of doctors in human rights abuses: report of a working party. London: Zed Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 112.The Hippocratic Oath. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html. Accessed Jan. 19, 2010.

- 113.Gellhorn A. Medical ethics—so what's the story? In Vitro. 1977;13(10):588–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02615108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Encyclopedia of bioethics. Revised ed. Vol. 5. New York: Simon & Schuster MacMillan; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rosner F. The life of Moses Maimonides, a prominent medieval physician. Einstein Quart J Biol Med. 2002;19:125–8. [Google Scholar]

- 116.McDonald J. Country Joe McDonald's Florence Nightingale tribute. Available at: http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/pledge.htm. Accessed Jan. 20, 2010.

- 117. Declaration of Geneva—Physician's Oath. General Assembly of World Medical Association; 1948.

- 118.Deltoff A, Deltoff M. One Profession—one oath? A survey of the disparity of the chiropractic oath. Chiropr History. 1988;8(1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Johnson C, Green B. Searching for a common international identity: a content analysis of oaths at chiropractic colleges. 2006. FCER Conference on Chiropractic Research, Chicago, IL.

- 120.Johnson C. Integrity and chiropractic. J Chiropr Med. 2007;6:43–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcme.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kao A, Parsi K. Content analyses of oaths administered at U.S. medical schools in 2000. Acad Med. 2004;79(9):882–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schwartz AB, Peterson EM, Edelstein BL. Under oath: content analysis of oaths administered in ADA-accredited dental schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(6):746–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]