Abstract

The Children-of-Twins design was used to test whether associations between marital conflict frequency and conduct problems can be replicated within the children of discordant twin pairs. A sample of 2,051 children (age 14–39 years) of 1,045 twins was used to estimate the genetic and environmental influences on marital conflict and determine whether genetic or environmental selection processes underlie the observed association between marital conflict and conduct problems. Results indicate that genetic and nonshared environmental factors influence the risk of marital conflict. Furthermore, genetic influences mediated the association between marital conflict frequency and conduct problems. These results highlight the need for quasiexperimental designs in investigations of intergenerational associations.

Marital Conflict and Conduct Problems in Children of Twins

Marital conflict is a robust predictor of children’s psychological adjustment, particularly symptoms of conduct disorder and other forms of externalizing psychopathology (Cummings & Davies, 1994, 2002; Emery, 1982; Grych & Fincham, 1990). This observation has led to the hypothesis that marital conflict causes children’s conduct problems. Several lines of research support the causal hypothesis. First, children exhibit physiological, affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to staged interadult conflict in laboratory experiments (e.g., El-Sheikh, Cummings, & Goetsch, 1989). There are, however, substantial individual differences in the magnitude and quality of children’s immediate reactions to conflict (Cummings, 1987). Moreover, it is unclear how and to what extent immediate reactions are translated into relatively stable, pathological modes of behavior. In addition, evidence indicates that children display comparatively better adjustment following divorce if the parents’ marital relationship was characterized by high levels of conflict (Booth & Amato, 2001). Finally, children whose parents remain in high-conflict marriages demonstrate poorer outcomes than children whose high-conflict parents divorce (Morrison & Coiro, 1999).

Alternatively, the relation between marital conflict and child conduct problems may reflect, to some extent, environmental or genetic selection processes, given that marital conflict does not occur at random (Fincham, Grych, & Osborne, 1994; Rutter, 1994). For example, low socioeconomic status, low educational attainment, and early age at first marriage and childbearing predict later marital discord and dissolution (Amato, 1996), while, simultaneously, these same environmental risks predict offspring behavior problems (Counts, Nigg, & Stawicki, 2005; Singh & Dagar, 1982; Wakschlag, Gordon, & Lahey, 2000). Consequently, nonrandom selection of children with young, impoverished, poorly educated parents into exposure to high conflict may partly underlie observed associations. The critical difficulty in resolving the relative roles of selection and causal processes is that marital conflict, like any other psychosocial risk indicator, is embedded within the larger context of families’ environmental circumstances and genetic predispositions, multiple aspects of which also predict child adjustment.

Particularly suggestive of selection processes are the relations among child conduct problems, adult antisocial behavior, and marital conflict. In a longitudinal study of antisocial behavior in three generations, Smith and Farrington (2004) found that, within each generation, child antisocial behavior predicted both adult antisocial behavior and severe marital conflict. They argued that marital conflict reflected a more aggressive style of interpersonal interaction and that deviant partner relationships were a part of “the maintenance of the antisocial lifestyle.” Furthermore, antisocial adults are more likely to marry a similarly antisocial spouse and subsequently divorce (Champion, Goodall, & Rutter, 1995; Robins, 1966). Indeed, difficulty with stable, monogamous relationships is a diagnostic hallmark of antisocial pathology in adults. Parental antisocial behavior, in turn, strongly predicts child conduct problems (Frick & Loney, 2002), although it remains unclear to what extent this association is due to inheritance of genetic liabilities versus disruptive parenting and other adverse environmental experiences. Emery, Waldron, Kitzmann, and Aaron (1999) found that women’s adolescent delinquency predicted an increased likelihood of divorce and nonmarital childbearing 14 years later and predicted increased externalizing problems in their children. Therefore, the association between marital conflict and child conduct problems may be due, at least in part, to the adverse genetic and environmental effects of parental antisocial behavior problems.

In addition, other forms of adult psychopathology are related to both marital conflict and child conduct problems. Individuals with depression are more likely to engage in negative conflict strategies and to experience heightened conflict and distress in their close relationships (Du Rocher Schudlich, Papp, & Cummings, 2004). Many maladaptive marriage and parenting behaviors—including harsh punishment, inconsistent discipline, low levels of affection toward a child, and overt marital conflict—are more frequent in parents having diverse forms of psychopathology (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, Smailes, & Brook, 2001). Child conduct problems, in turn, are predicted by both parental depression (Kim-Cohen, Moffitt, & Taylor, 2005) and alcohol or substance abuse (Malone, Iacono, & McGue, 2002; Moss, Lynch, & Hardie, 2002), thus potentially confounding observed associations with marital conflict.

Finally, differences in marital conflict also reflect genetic differences between individuals. Obviously, there are no genes “for” arguing with a spouse, but the process of selecting, shaping, and perceiving one’s social environments involves genetically influenced behaviors and personality attributes (Plomin & Bergeman, 1991, Scarr & McCartney, 1983). In early explorations of this topic, Plomin and his colleagues (Chipuer, Plomin, Pedersen, McClearn, & Nesselroade, 1993; Plomin, McClearn, Pedersen, Nesselroade, & Bergeman, 1989) demonstrated that roughly a quarter of the variance in adults’ ratings of current family conflict and exposure to other family environments could be attributed to genetic factors, only a fraction of which were common to personality. Johnson, McGue, Krueger, and Bouchard (2004) demonstrated substantial genetic influences on marital status (h2 =.68) and on the co-variation between marital status and personality measures. Likewise, perceptions of marital satisfaction, cohesion, and adjustment are modestly influenced by genetic factors, although most individual differences can be attributed to environmental factors that are not shared between twins (Spotts et al., 2004). Genotypic factors also influence risk for divorce, to some extent, via effects on personality (Jockin, McGue, & Lykken, 1996; McGue & Lykken, 1992).

Overall, evidence indicates that genetic factors influence marital status, satisfaction, conflict, and dissolution. To some extent, genetic influence may be mediated via vulnerability to antisocial behavior, depressive disorder, or other characteristics of personality or temperament, although research on potential mediators of genetic influence is very limited. Furthermore, children inherit these same genetic factors, rendering the conflictual environment that children experience closely related to their genetic liabilities, a phenomenon termed passive gene–environment correlation (rGE) in the behavior genetics literature (see Rutter & Silberg, 2002 for a more thorough discussion of rGE). If the same genotypic factors influence both marital conflict and the development of conduct problems in children, then the purported effects of marital conflict would reflect the nonrandom selection of children with genetic liabilities for conduct problems into high-conflict families. Given the magnitude of genetic influences on child conduct problems (Arsenault et al., 2003; Scourfield, Van den Bree, Martin, & McGuffin, 2004; Slutske et al., 1997), this is a critical alternative hypothesis.

Quasi-experimentation and the Children-of-Twins Design

Marital conflict is associated with children’s conduct problems, as well as with a number of other environmental and genetic risk indicators, but considerable ambiguity remains regarding the processes underlying these associations. First, no previous investigation of the relation between marital conflict and child adjustment has utilized genetically informative data; thus, the existing marital conflict literature is silent regarding the role of biological inheritance. Second, the origin of a psychosocial risk indicator is not necessarily the same as the mechanism of its effect, as made obvious by an analogy of smoking: The personality predictors of smoking initiation are completely independent of the mechanisms by which smoking causes lung cancer (Rutter, Silberg, & Simonoff, 1993). Genetic influence on marital conflict, therefore, does not necessarily indicate that associations between marital conflict and child adjustment are genetically mediated. Third, multiple social and biological risk factors undoubtedly exert a causal influence on child conduct problems; a recent review by Dodge and Pettit (2003) outlines numerous domains of potential influence on conduct disorder, including neighborhood, peer, school, family, and individual characteristics. Combinations of environmental and genetic liabilities, therefore, may reflect multiple sources of causation acting in concert rather than spurious relations between conflict and conduct problems. Rutter and his colleagues (Rutter, 2005; Rutter & Silberg, 2002; Rutter, Pickles, Murray, & Eaves, 2001) have outlined several research strategies for resolving the ambiguity regarding the processes underlying associations between multiple risk indicators and psychological adjustment. Primary among them is quasi-experimentation, to “pull apart” (i.e., reduce or eliminate covariation between) the risk variables of interest and variables governing selection into risk exposure. In addition, the specification of alternative explanatory hypotheses about risk mechanisms—such as environmental experience, biological inheritance, or both mechanisms operating in concert—is preferable to the consideration of any one hypothesis in isolation.

The Children-of-Twins design (Heath, Kendler, Eaves, & Markell, 1985; Nance & Corey, 1976), a powerful quasi-experimental design for examining the processes underlying intergenerational associations, is useful for both of these goals. In a comparison of a pair of identical twins and their respective children, in which Twin A experiences more frequent conflict than Twin B, and the children of Twin A demonstrate more conduct problems than the children of Twin B, the within-twin pair association cannot be attributed to any genetic or environmental influences that do not vary between the twin parents, thus effectively pulling apart the effects of marital conflict from the effects of all selection variables common to twins. In this way, the relative roles of selection and causation processes in the association between marital conflict and child conduct problems may be assessed. To the extent that children of twins discordant for marital conflict exhibit similar levels of conduct problems, selection variables shared by twins (rather than marital conflict, per se) account for some part of the intergenerational association for replicating associations between marital conflict and conduct problems. Conversely, causal processes are suggested to the extent that children of twins discordant for marital conflict differ in their level of conduct problems (Dick, Johnson, Viken, & Rose, 2000; D’Onofrio et al., 2003, 2005; Gottesman & Bertelsen, 1989; Jacob et al., 2003). In the current report, the first investigation of marital conflict to use a quasiexperimental design capable of controlling for genetic selection effects, the relation between marital conflict frequency and children’s conduct problems was examined in a sample of 2,051 children of twins.

Method

Participants

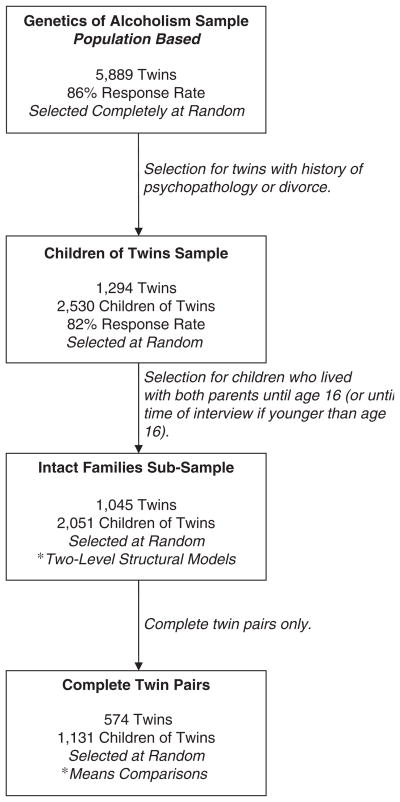

Participants were twins from a volunteer twin register, formed in 1978 and maintained by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and their offspring. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships among four Australian twin subsamples. The primary subsample to be utilized in the present research is the Intact Families Sub-Sample, but understanding the composition of this subsample necessitates describing all four.

Figure 1.

Relations among Australian twin and children-of-twins samples.

First, in 1993–1995, 5,889 twins (86% response rate) were interviewed by telephone as part of an ongoing investigation of the genetics of alcoholism (Genetics of Alcoholism Twin Sample; Heath et al., 1997). The mean ages at the 1993 interview were 42.7 years for men (range =28–89 years) and 44.8 years for women (range =27–90 years). In keeping with the low proportion of ethnic minorities in the non-Aboriginal Australian population, the twins were almost exclusively of European ancestry. The sample mirrors other population demographics as well. Previous analyses have found no effects of self-selection for marital status, religious affiliation, frequency of church attendance, personality traits, mental illness, and abnormal behavior (Heath et al., 1997; Slutske et al., 1997). The Genetics of Alcoholism Sample does overrepresent monozygotic (MZ) twins, overrepresents twins born before 1930, and under-represents twins with less than an 11th grade education (Slutske et al., 1997). Cooperation bias and the underrepresentation of poorly educated participants, however, have been shown to have negligible effects on behavioral genetic analyses of conduct disorder (Heath et al., 1996). Overall, the Genetics of Alcoholism Sample can be considered broadly generalizable to the non-Aboriginal Australian population.

Between 1998 and 2001, investigators contacted a selected subsample of the 1993 interview sample’s offspring (Children-of-Twins Sample). Selection targeted offspring considered at-risk for conduct disorder, depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and/or divorce, as well as a control group considered to be at low risk (D’Onofrio et al., 2005). In total, 2,530 offspring from 406 twin pairs, as well as offspring from 482 individual twins without co-twins, participated in the study (an 82% response rate). Of the children of twins, 51% came from nuclear families in which the twin parent did not have a history of psychopathology or divorce, and 24% came from nuclear families in which neither the twin parent nor the co-twin had a history of psychopathology or divorce.

The Intact Families Sub-Sample was restricted to the offspring from the Children-of-Twins Sample who reported residing with their parents until the age of 16 or until the time of the interview if the child was younger than 16 years old. This subsample was constructed because children who did not reside with their parents until the age of 16 were not interviewed regarding their parents’ marital conflict. The Intact Families Sub-Sample excluded some children whose siblings were included, because siblings did not necessarily agree on whether they lived with both parents until the age of 16. In some cases, this within-family disagreement may have been due to reporter error. In other cases, it may have been due to the timing of the parental divorce/death (i.e., falling after the 16th birthday of the eldest children, with their younger siblings experiencing the divorce/death at an earlier age). Sibling disagreement, however, was rare: only 72 of the 1,294 nuclear families in the Children-of-Twins Sample had discrepant reporting (5.8%). Restriction to intact families excluded the children of 14 complete twin pairs, as well as the children of 188 individual twins whose co-twin’s family was included. In total, 2,051 children of 1,045 twins (274 pairs and 507 individual twins) comprised the Intact Families Sub-Sample. The number of children per nuclear family ranged from one to six; the mean number of siblings per nuclear family was approximately two. The children’s age at assessment ranged from 14 to 39 years (M =25.1; SD =5.7).

Finally, the Complete Twin Pairs Sub-Sample excluded nuclear families if data were missing on the twin parent’s cotwin’s nuclear family (i.e., children of incomplete twin pairs). The Complete Twin Pairs sample was constructed for analyses requiring information on both twins; in total, it was composed of 1,131 children of 272 twin pairs. As discussed below, the subsample utilized in our primary analyses (structural equation modeling) was the Intact Families Sub-Sample. In addition, the Complete Twin Pairs Sub-Sample was used for a purely illustrative analysis (descriptive means comparisons).

Measures

Zygosity was determined by questionnaire responses concerning physical similarity and frequency of occasions where twins were mistaken for each other. When there was disagreement between co-twins about zygosity or when zygosity assignment was otherwise ambiguous, further information, including photographs, was requested. Comparisons of these zygosity assignments with multilocus genotyping have shown the self-report questions to be >95% accurate (Eaves, Eysenck, & Martin, 1989). In addition, final zygosity assignments from questionnaire responses demonstrated perfect agreement with zygosity assignment based on DNA typing of eight polymorphic markers in a subsample of 190 twin pairs (Duffy, 1994).

Marital conflict frequency and offspring conduct problems were assessed using the Semi-structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism, OZ Twin 89 Version (SSAGA – OZ), a comprehensive psychiatric interview designed for genetic studies of alcoholism, modified for use over the telephone (Bucholz et al., 1994). The SSAGA is derived from the National Institutes of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Helzer & Robins, 1988), The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 3rd ed. – revised (DSM – III – R; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1992), The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978), The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins et al., 1988), and The HELPER Interview (Coryell, Cloninger, & Reich, 1978). Interrater reliability of the SSAGA for assessment of Conduct Disorder is good (Yules Y =.65, tetrachoric r =.78; Slutske et al., 1997). In addition, the SSAGA’s test – retest reliability (over a 15-month interval) for retrospective lifetime diagnoses of conduct disorder is good (κ=.52, Yules Y =.68, tetrachoric r =.78; Slutske et al., 1997). Interviews were administered by trained lay interviewers who were supervised by a trained clinical psychologist. All interviews were audiotaped, and a randomly selected 5% of the interviews were reviewed for quality control and check of coding inconsistencies.

The children of twins reported on their parents’ marital conflict, answering two questions: “How much conflict and tension was there between your parents in your household when you were 6 to 13 [years old]?” (Tension) and “How often did your parents fight or argue in front of you?” (Arguing). Answers to both questions were scored on a 4-point ordinal scale, where higher scores indicated more frequent marital conflict (Tension: median =2, SD =0.854; Arguing: median =2; SD =0.968). The polychoric correlation between responses to the two items was .816. Very frequent conflict was somewhat rare: 81.7% of offspring reported “None” or “A little” conflict and tension, and 71.81% of offspring reported that their parents “Never” or “Sometimes” argued in front of them. Nevertheless, the proportions of children reporting “Some” or “A lot” of conflict and tension (19.3%) and that their parents “Often” or “Always” argued in front of them (28.19%) are roughly consistent with previous research suggesting that approximately 20% of a community sample can be qualitatively characterized as “discordant” (Beach, Fincham, Amir, & Leonard, 2005). Marital conflict scores for each child were obtained by summing his or her scores on the two items (median =4; SD =1.603) and then transforming the sums to rank scores. Children in the same nuclear family (i.e., siblings) agreed moderately well on their parents’ marital conflict (intraclass correlation =.603 in MZ twin families; .536 in dizygotic [DZ] twin families). The linear and quadratic effects of age accounted for <3% of the variance in marital conflict reports. The effects of age and gender on marital conflict reports were partialed before analyses.

Children also retrospectively reported the incidence of DSM – III – R Conduct Disorder symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), up to age 18 years (or their current age, if under 18 years old). Children answered questions such as the following: “Did you ever run away from home overnight?” or “Did you ever start fires with the intention of causing damage?”. One symptom, forcing another in sexual intercourse, did not figure into the analysis because no participant endorsed it. The modal number of symptoms reported was 0 (26% of males; 45% of females); symptom counts ranged from 0 to 13, out of a maximum 15 possible. Offspring conduct problem scores were obtained by counting the number of endorsed symptoms (M =1.783, SD =2.064) and, for the purposes of structural equation modeling, transforming to rank scores. As suggested by the preponderance of zero symptoms counts, clinical-level pathology was infrequent: approximately 12% of children met diagnostic criteria for Conduct Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), a prevalence rate consistent with population-based behavior genetic samples in the United States (11.48%; Foley et al., 2004) and in Finland (14.7% in boys and 8.4% in girls; Rose, Dick, Viken, Pulkkinen, & Kaprio, 2004). Accordingly, symptom counts were used in lieu of clinical diagnoses, in order to reflect the full range of outcomes in the general population.

Siblings were less similar in conduct problems than in their report of marital conflict (intraclass correlation =.237 for children of MZ twins; .271 for DZ children). Children’s conduct problems were modestly but significantly correlated with their reports of tension (polychoric r =.175; p<.001) and arguments (polychoric r =.113; p<.001). The effects of gender and age were partialed out of offspring conduct scores before data analysis. The linear and quadratic effects of age accounted for <1% of the variance in reports of childhood conduct problems.

Correction for Sample Selection

As mentioned above, the Intact Families Sub-Sample was utilized for our primary analyses; however, similar to many genetic epidemiological studies, the Intact Families Sub-Sample is a product of deliberate selection on stratification variables (parental psychiatric history and marital status), in conjunction with potentially nonrandom self-selection. Without addressing this sample selection problem, our analyses may be biased. In general, sample selection may be considered a case of missing data, with data on the variables of interest only present in selected twins and their families (Bechger, Boomsma, & Koning, 2002). Accordingly, sample selection may be considered within Rubin’s theory of missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987; Rubin, 1976). Missingness (i.e., selection) is considered ignorable not only when participants are a random sample from the general population (selected completely at random; SCAR) but also when selection depends on the values of other variables, related to the variables of interest, observed in both selected and unselected participants (selected at random; SAR).

As detailed above, the Intact Families Sub-Sample is derived from a larger, population-representative twin sample (the Genetics of Alcoholism Twin Sample), in which multiple sociodemographic and psychiatric characteristics, including the deliberate selection variables, were observed for both selected and unselected twins. Therefore, the Intact Families Sub-Sample may be considered SAR. Following Heath, Madden, and Martin’s (1998) procedure for developing and testing models of nonresponse in SAR data, multiple logistic regression was used to identify predictors of whether or not a twin pair (i.e., at least one twin) from the Genetics of Alcoholism Twin Sample participated in the Intact Families Sub-Sample. Pair-wise participation, rather than individual twin participation, was predicted because sample selection occurred on the pair level. Socio-demographic and psychiatric characteristics assessed using the SSAGA – OZ were used as predictors of selection into the Intact Families Sub-Sample (see Bucholz et al., 1994 or Heath et al., 1998 for more details). Dummy variables were used to code for the presence of psychiatric disorders, behaviors related to heavy alcohol use, and family psychiatric history in one or both twins, as well as for cohort categories (see Table 1 for list). Propensity weights were then constructed using the predicted probability of a pair participating in the Intact Family Sub-Sample, as calculated from the logistic regression model (for details on standard methods of data weight construction, see Heath et al., 1998 or Lee, Forthofor, & Lorimor, 1989). Our model for selection was tested by comparing the unweighted and weighted frequency distributions of sociodemographic and psychiatric characteristics in the Intact Families Sub-Sample with the distributions in the Genetics of Alcoholism Sample. Finally, each twin family was weighted appropriately in structural equation modeling. Despite data clustering, all methods for single-level data weighting are applicable, because weights are present at the highest level of clustering only (Asparauhov, 2004).

Table 1.

Comparison of Sociodemographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of the Genetics of Alcoholism Sample and the Intact Families Sub-Sample, Before and After Data Weighting

| Genetics of Alcoholism Sample (%) | Intact Families Sub-Sample (%) | Odds ratios** | Weighted Intact Families Sub-Sample (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Cohort | ||||

| Females, under 35 | 23.25 | 4.61* | 1.0 | 18.04 |

| Females, 35–45 | 19.28 | 31.75* | 17.62 (11.65–26.65) | 22.99 |

| Females, over 45 | 25.19 | 31.50* | 52.45 (30.30–90.80) | 21.19 |

| Males, under 35 | 15.35 | 1.28* | 0.20 (0.09–0.44) | 17.77 |

| Males, 35–45 | 9.04 | 16.52* | 8.28 (4.66–14.70) | 11.56 |

| Males, over 45 | 7.90 | 14.34* | 39.54 (20.25–77.20) | 8.45 |

| Age (mean) | 43.59 | 45.53* | 0.92 (0.91–0.94) | |

| Pair gender | ||||

| Male – male | 17.83 | 24.84* | 2.54 (1.56–4.15) | 20.74 |

| Female – male | 25.76 | 21.77* | – | 27.61 |

| Female – female | 56.41 | 53.29* | 1.0 | 51.65* |

| Discordant pairs | ||||

| Family alcohol use history | ||||

| Twin | 11.18 | 12.29 | 0.77 (0.51–0.99) | 16.08* |

| Father | 10.70 | 11.27 | – | 18.89* |

| Mother | 2.92 | 2.94 | – | 2.30 |

| Spouse | 12.30 | 16.90* | – | 14.42 |

| Family depression history | ||||

| Twin | 27.88 | 35.98* | – | 31.30 |

| Father | 17.51 | 19.85 | – | 6.57* |

| Mother | 23.48 | 24.33 | – | 28.93* |

| Spouse | 20.59 | 29.83* | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) | 23.77 |

| Agoraphobia | 5.41 | 6.15 | 0.57 (0.35–0.93) | 5.99 |

| Panic | 1.64 | 2.69 | – | 1.39 |

| Social phobia | 3.20 | 4.87* | – | 3.37 |

| Other phobias | 2.72 | 4.10 | – | 2.88 |

| Abstain from alcohol | 3.37 | 3.33 | – | 3.04 |

| High-frequency drinking | 27.44 | 31.50 | – | 28.25 |

| High-density drinking | 19.71 | 20.23 | – | 21.31 |

| High maximum number of drinks | 20.51 | 17.67 | – | 17.10* |

| Migraine | 38.94 | 35.21 | – | 33.71* |

| Suicidal ideation | 3.81 | 6.53* | – | 6.57* |

| Major depression | 31.41 | 40.97* | 1.52 (1.22–1.90) | 35.39* |

| Alcohol dependence | 13.54 | 21.25* | 2.06 (1.55–2.74) | 18.26* |

| Conduct disorder | 8.53 | 13.44* | 1.79 (1.29–2.49) | 10.99* |

| Concordant pairs | ||||

| Family alcohol use history | ||||

| Twin | 1.16 | 2.69* | – | 3.78* |

| Father | 8.57 | 14.21* | – | 13.27* |

| Mother | 1.32 | 2.69* | – | 2.01 |

| Spouse | 0.84 | 1.54 | – | 0.76 |

| Family depression history | ||||

| Twin | 6.65 | 12.55* | – | 9.04* |

| Father | 5.57 | 8.19* | – | 0.39 |

| Mother | 8.89 | 16.39* | – | 9.83 |

| Spouse | 1.80 | 4.23* | – | 2.18 |

| Agoraphobia | 0.20 | 1.66* | – | 0.67 |

| Panic | 0.00 | 0.26* | – | 0.06 |

| Social phobia | 0.08 | 0.38 | – | 0.15 |

| Other phobias | 0.08 | 0.26 | – | 0.12 |

| Abstain from alcohol | 0.72 | 1.15 | – | 0.75 |

| High-frequency drinking | 10.34 | 14.21 | – | 15.05* |

| High-density drinking | 3.73 | 4.87 | – | 6.91* |

| High maximum number of drinks | 4.49 | 3.33 | – | 7.27* |

| Migraine | 19.79 | 32.52* | 1.47 (1.15–1.88) | 28.26* |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.16 | 0.77* | – | 0.39 |

| Major depression | 8.05 | 15.36* | 1.46 (1.02–2.09) | 12.15* |

| Alcohol dependence | 2.80 | 5.51* | 2.19 (1.23–3.91) | 6.34* |

| Conduct disorder | 1.44 | 3.20* | – | 2.58* |

Note. DZ =dizygotic; MZ =monozygotic.

Univariate comparisons with nonselected participants from the Genetics of Alcoholism Sample are significant, p<.05.

All listed odds ratios are significantly different from 1; p<.05. 95% confidence intervals are shown in parentheses. Nonsignificant odds ratios for remaining predictors are not shown.

Table 1 summarizes the observed frequency distributions for sociodemographic characteristics, family history of alcohol use and depression, alcohol use behaviors, and psychiatric disorders of twin pairs participating in the Intact Families Sub-Sample compared with nonselected twins from the population-representative Genetics of Alcoholism Sample. Based on univariate comparisons, selected twin pairs were different from nonselected pairs in multiple respects, including cohort, age, pair gender, family history of alcohol and depression, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic suicidal ideation, major depression, alcohol dependence, conduct disorder, and migraine. Also summarized in Table 1 are partial odds ratios estimated from a multiple logistic regression predicting participation in the Intact Families Sub-Sample. The following were significant predictors of sample selection: (a) cohort; (b) age; (c) concordant for male gender; (d) discordant for twin history of alcohol use; (e) discordant for spouse history of depression; (f) discordant for agoraphobia; (g) discordant for major depression; (h) discordant for alcohol dependence; (i) discordant for conduct disorder; (j) concordant for migraine; (k) concordant for major depression; and (l) discordant for alcohol dependence. Finally, the right-hand columns of Table 1 summarize the frequency distributions for the Intact Families Sub-Sample when pairwise propensity weights were used, which may be used to examine whether data weighting removed differences between selected and nonselected participants. Of the significant predictors of sample selection identified by multiple logistic regression, differences in mean age, as well as frequency differences in cohort, concordance for male gender, discordance for spouse history of depression, and discordance for agoraphobia were removed by data weighting. In addition, frequency differences in discordance for twin history of alcohol use, major depression, alcohol dependence, and conduct disorder; and concordance for migraine, major depression, and alcohol dependence were substantially reduced, although univariate comparisons remained statistically significant. Residual differences in the frequency of psychiatric disorders may be evident even after data weighting because the probability of selection was heavily driven by sociodemographic characteristics, particularly cohort, as illustrated by the extreme odds ratios associated with cohort dummy variables.

Results

Descriptive Means Comparison

In order to illustrate the within-twin pair association between marital conflict and conduct problems, we compared the mean number of conduct problems (raw, not rank-transformed, symptom counts) in four groups of children: (a) children whose parents and whose parents’ co-twins (i.e., the children’s aunts/uncles) both had low-conflict marriages (n =823 children of 197 twin pairs); (b) children whose parents had a low-conflict marriage but whose parents’ co-twins had a high-conflict marriage (n =132 children of 29 twin pairs); (c) children whose parents had a high-conflict marriage but whose co-twins had a low-conflict marriage (n =141 children from 37 twin pairs); and (d) children whose parents and whose parents’ cotwins both had high-conflict marriages (n =35 children from 9 twin pairs). Low-and high-conflict marriages were dichotomized by summing each child’s ratings of his or her parents’ marital conflict on the two survey items and averaging these sums over all the siblings in a nuclear family, yielding a single score for each twin’s marital conflict that ranged between 2 and 8. Twins whose scores were ≤ 4 (the median score) were classified as low conflict; otherwise, they were classified as high conflict.

The means’ comparisons were conducted separately in MZ and DZ twin families from the Complete Twin Pairs Sub-Sample. (Information on both twins was necessary to classify children into groups accurately). No formal significance tests were conducted because observations were nonindependent and the inclusion of variable numbers of children per nuclear family weighted some families more heavily than others. This analysis was intended only to illustrate the within-twin pair association between conflict and conduct problems, and it should be considered entirely descriptive. Unweighted data were used for this analysis, because it did not involve inferential statistics.

The key comparison is the difference in means between the children of twins who are discordant for their level of marital conflict (second and third groups): Does the twin with higher marital conflict than his or her co-twin have children with more conduct problems? To the extent that influences specific to the twin (including marital conflict, non-shared environmental influences, and the genetic and environmental influences of the twin spouse) are associated with children’s conduct problems, a mean difference between the second and third groups will be evident. If environmental influences shared by twins, such as demographic variables, account for the association between conflict and conduct problems, no mean difference will be evident between children of twins discordant for marital conflict. If genetic influences account for the association between conflict and conduct problems, there will be a greater mean difference evident in the DZ twin family comparison, wherein genetic influences on the twin parents are partially controlled, than in MZ twin families, wherein the genetic influences on the twin parents are completely controlled.

Table 2 shows the mean number of conduct problems in children grouped according to the level of conflict in the marriages of their parents (labeled parental) and their parents’ twins (labeled avuncular). The overall pattern of the means is consistent with the conclusion that the association between children’s conduct problems and parents’ marital conflict is accounted for by common genetic liabilities. The children in the first group, with low parental and avuncular conflict, were unrelated to the children in the fourth group, with high parental and avuncular conflict. This comparison, then, is confounded by genetic and environmental differences between families. The mean number of conduct problems tended to increase with higher overall amounts of conflict in the twin family, with children whose parents and parents’ co-twins had a low-conflict marriage having the lowest mean number of conduct problems and children whose parents and parents’ co-twins had a high-conflict marriage having the highest mean number of conduct problems. The within-twin pair association is illustrated by the comparison between children of discordant twin pairs (second and third groups). In MZ twin families, children whose parents had a low-conflict marriage but whose parents’ co-twins had a high-conflict marriage did not tend to have fewer conduct problems than those children whose parents had a high-conflict marriage but whose parents’ co-twins’ had a low-conflict marriage—a comparison that controls for genetic and environmental influences shared by twin parents. In DZ twin families, however, children whose parents had a low-conflict marriage but whose parents’ co-twins had a high-conflict marriage did tend to have fewer conduct problems than those children whose parents had a high-conflict marriage but whose parents’ co-twins’ had a low-conflict marriage. The DZ twin family comparison controls for all shared environmental influences on the twin parent but only 50% of genetic influences. The difference between the pattern evident in MZ families and DZ families thus provides initial evidence that genetic influences account for the association between marital conflict frequency and conduct problems.

Table 2.

Mean Number of Conduct Disorder Symptoms by Parental and Avuncular Level of Conflict, in Complete Twin Pairs Sub-Sample

| Family pattern | MZ twins’ children |

DZ twins’ children |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| 1. Parental low – avuncular low | 1.652 | 2.072 | 1.695 | 2.015 |

| 2. Parental low – avuncular high | 1.983 | 1.925 | 1.589 | 1.731 |

| 3. Parental high – avuncular low | 1.857 | 1.782 | 2.203 | 2.290 |

| 4. Parental high – avuncular high | 2.536 | 2.937 | 3.143 | 1.952 |

Note. DZ =dizygotic; MZ =monozygotic.

Only children of complete twin pairs are included.

Two-level Structural Equation Models

Description

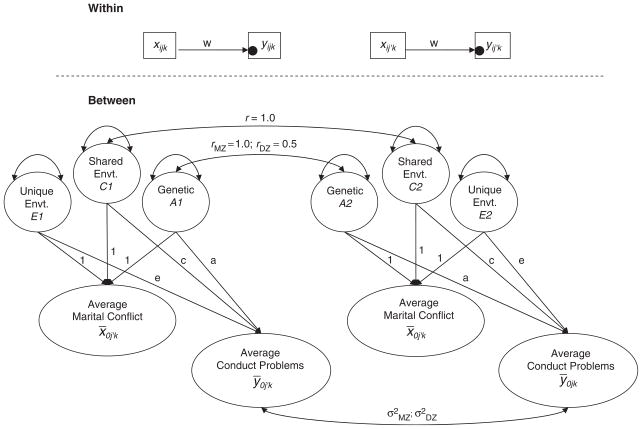

In contrast to the first, purely descriptive analysis, our second analysis was designed to estimate more rigorously the relative roles of genetic and environmental selection factors in inter-generational associations between marital conflict frequency and conduct problems. Previous investigations using the Children-of-Twins design have utilized either multivariate structural equation models (SEM) including only one child per twin parent (e.g., D’Onofrio et al., 2003; Heath et al., 1985) or hierarchical linear models (HLM) including multiple children per twin parent (e.g., D’Onofrio et al., 2005; Mendle et al., 2006). The advantage of the former is explicit quantification of latent genetic and environmental influences on the parental phenotype, but the exclusion of all but one child per nuclear family does not allow the examination of parity differences in child adjustment and sacrifices power (D’Onofrio et al., 2003). The advantage of the latter is an increase in power to estimate intergenerational paths, but HLM results are difficult to parameterize in terms of genetic or environmental latent variables (but see McArdle & Prescott, 2005). In order to capitalize on the advantages of both of these methods, we utilized an analytic strategy that combined the explicit quantification of latent variables provided by multivariate SEM with the accommodation of multiple children per nuclear family: two-level SEM. Our two-level SEM is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Two-level structural model of marital conflict and conduct problems. x represents marital conflict frequency; y represents conduct problems. Alphabetical subscripts indicate measurement of the ith child in the jth nuclear family in the kth twin family. Filled circles on the “Within” level represent random intercepts. Double-headed curved arrows over A, C, and E components represent estimated variances.

The top portion of the model, labeled “Within,” reflects relationships within the nuclear family. The nuclear families of the first and second members of each twin pair are represented separately, with the children of the first members of each twin pair on the left and the children of the second members of each twin pair on the right. The conduct problems of the ith child in the jth nuclear family of the kth twin family (yijk) are predicted by the frequency of his or her own exposure to marital conflict (xijk), as represented by the path labeled w, and by the average number of conduct problems in his or her nuclear family, that is, the random intercept represented by the circle at the end of the w path. To the extent the child who reports more marital conflict than his or her siblings also reports more conduct problems than his or her siblings, this is reflected in the w path.

The bottom portion of the model, labeled “Between,” reflects relationships between nuclear families (within-twin pairs). The average levels of marital conflict in each nuclear family are represented here by the circles labeled x̄0jk and x̄0j′k. In addition, similar to the standard twin design path model, the variance in average marital conflict is decomposed into three components: variance due to additive genetic influences (A), variance due to other environmental influences shared by twins (C), and variance unique to each twin (E). By definition, C variance is completely shared by twins, while 50% of A variance is shared by DZ twins and 100% of A variance is shared by MZ twins. Readers may be more familiar with a twin model parameterization in which the A, C, and E components are standardized and the paths from them freely estimated. The current model is simply a reparamaterization with the paths fixed to one and the variances freely estimated. Because the paths are fixed to one, the scale of each component is defined by the marital conflict variable, and the total variance in marital conflict is the sum of the estimated variances of the A, C, and E components. Dividing the estimated variance of A by the total variance of average marital conflict yields the familiar heritability proportion, h2. For more detail concerning variations on twin and family models, see Neale and Cardon, 1992. Note that averaging the reports of all the children in each nuclear family aggregates information on each couple’s marital conflict from up to six independent reporters.

The average nuclear family conduct problems are regressed on the variance components of the parents’ marital conflict—A, C, and E. The regression of conduct problems on A (a) represents the effect of genetic variance in marital conflict on children’s conduct problems. The regression of conduct problems on C (c) represents the impact of the shared environmental variance in marital conflict on conduct problems. The regression of conduct problems on E (e) estimates the effect of unique environmental variance in marital conflict on conduct problems. Because the genetic relatedness of cousins differs by zygosity, the residual covariance between nuclear families’ average conduct problems is estimated separately for MZ and DZ twin pairs.

All of the parameters of the two-level ACE model are theoretically justified, but they are not necessarily identified (D’Onofrio et al., 2003). If the variance of a component of parents’ conflict is negligible, then that component cannot mediate the relationship between parent and child. If a variance component is zero, then the path from that component to the children’s conduct problems is dropped. In order to ensure model identification, we began by only estimating the variance of the A, C, and E components of the mean marital conflict frequency reported by all the children in a nuclear family. We then proceeded by estimating intergenerational paths only from those variance components with nonnegligible contributions to the parental phenotype.

All two-level SEMs were fit to data from the Intact Families Sub-Sample, using pairwise propensity weights to correct for sample selection. The significance of each individual path was tested by fitting a series of nested models and examining the differences in fit. All two-level structural models were fit using MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004). Each twin pair and their respective children were weighted with the pairwise weights described above. Models were compared using two measures of goodness of fit, BIC and RMSEA, as well as differences in chi-square. BIC is an information-theoretic fit criterion that estimates the Bayes factor, the ratio of posterior to prior odds in comparisons of a model with a saturated one (Raftery, 1993; Schwarz, 1978). BIC outperforms other fit criteria in its ability to discriminate between multivariate behavior genetic models, particularly for complex model comparisons in large samples, and is more robust to distributional misspecifications (Markon & Krueger, 2004). Interpretation of BIC values is entirely comparative, with lower values of BIC indicating a better model fit. RMSEA measures error in approximating data from the model per model parameter (Steiger, 1990). RMSEA values of <.05 indicate a close fit, and values up to .08 represent reasonable errors of approximation. Browne and Cudeck (1993) have argued that the RMSEA provides very useful information about the degree to which a given model approximates population values. Differences in model chi-square are themselves distributed as chi-square, with df equal to the difference between the models’ df.

The variability in conduct problems explained by marital conflict frequency can be assessed using the proportional reduction in prediction error, or R2. In the two-level case considered here, there are two components of error: (a) deviations of individual children’s conduct problems from their nuclear family mean; and (b) deviations of nuclear families’ mean conduct problems from the overall population mean. Accordingly, we can define two concepts of “variance explained”: (a) proportional reduction of error for predicting an individual child’s conduct problems, referred to here as Within R2, and (b) proportional reduction of error for predicting a nuclear family’s mean conduct problems, referred to here as Between R2 (Snijders & Bosker, 1994). Snijders and Bosker (1999) give a complete treatment of how suitable multilevel estimates for R2 can be calculated manually; the estimates shown here are calculated automatically by the Mplus software.

Interpretation

The e path is the key test of the within-twin pair association. If the member of the MZ twin pair who experiences more marital conflict than his or her co-twin has children with more average conduct problems than the children of the cotwin, an association that controls for genetic and environmental influences on the twin, this is reflected in e. Remember that MZ twins are identical for both genetic influences (A) and the shared environment (C). MZ twins differ only in their values for the latent variable E, with higher values for E indicating high frequencies of marital conflict relative to one’s co-twin. The regression of child conduct problem on E, then, estimates the degree to which child conduct problems are predicted by differences in marital conflict between MZ twin pairs. (In lieu of estimating an e path, some previous SEMs of the Children-of-Twins design (e.g., D’Onofrio et al., 2003; Silberg & Eaves, 2004) have fit a direct “causal” path from the parental phenotype to the child phenotype. The present model is a functionally identical reparameterization of a “direct path” model (D’Onofrio et al., 2003). Indeed, if such a “direct path” were estimated it would be identical to e.)

The roles of genetic and shared environmental selection effects are estimated in the a and c paths. If discordant twins have children with similar numbers of conduct problems—that is, it does not seem to matter whether a child’s parent or his aunt/uncle engage in frequent conflict—this is reflected in the “selection effect” paths, a and c. Furthermore, if the children of discordant MZ twins have more similar numbers of conduct problems than the children of discordant DZ twins, this is reflected in the genetic path from parent to child, a. It is important to note that the a path is not testing whether there are genetic influences on conduct problems, which is hardly in dispute (Slutske et al., 1997), but to what extent these genetic influences on child conduct underlie the association with marital conflict.

The results of the two-level parental models are summarized in the left columns of Table 3. The first parental model estimated the variances of the additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and non-shared environmental (E) components of the twins’ marital conflict. The negative estimated variance for C was not surprising, given that the correlation between DZ twins’ marital conflict (rDZ = .035) was less than half the MZ twin correlation (rMZ = .398). A negative C variance is evidence for epistatic or other nonadditive genetic effects.

Table 3.

Estimated Parameters of Parental and Intergenerational Models, in Intact Families Sub-Sample

| Fit index | Parental models |

Intergenerational models |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | AE | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| BIC | 5,331.460 | 5,328.565 | 9,652.926 | 9,650.151 | 9,653.785 |

| RMSEA | 0.090 | 0.091 | 0.063 | 0.062 | 0.064 |

| χ2 | 75.079 | 76.387 | 105.647 | 107.076 | 110.710 |

| df | 9 | 10 | 25 | 26 | 26 |

| Between R2 | 0.150 | 0.239 | 0.139 | ||

| Parameter | |||||

| w | 0.130* | 0.137* | 0.130* | ||

| A | 0.555* | 0.264* | 0.261* | 0.280* | 0.180 |

| C | −0.261 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 0.362* | 0.391* | 0.397* | 0.377* | 0.470* |

| a | – | – | 0.295* | 0.387* | 0 |

| e | – | – | 0.098 | 0 | 0.227 |

| σ2(x̄0jk, x̄0j′k) MZ | – | – | 0.072 | 0.060 | 0.070 |

| σ2(x̄0jk, x̄0j′k) DZ | – | – | −0.038 | −0.041 | −0.040 |

Note. R2 values represent proportion of between-family variance in conduct problems accounted for.

p ≤ .05.

We fit a second parental model that estimated only the variances of A and E and fixed the variance of C to zero. Judging from the fit indices listed in Table 3, fixing the variance of C to zero did not significantly decrease the fit of the model. The change in chi-square was statistically insignificant (Δχ2 =1.308, Δdf =1, p =.253). From the estimates of this second parental model, additive genetic influences accounted for approximately 40% of the variance in marital conflict. Nonshared environmental influences accounted for the remaining 60% of the variance in marital conflict. These results suggest that both genetics and the unique environment contribute to parents’ marital conflict, thus confirming the need to study the consequences of marital conflict in a way that takes into account genetic selection effects.

The next series of intergenerational models examined the relationships between the genetic and non-shared environmental influences involved in the parents’ marital conflict and children’s outcomes. The variance of C remained fixed at zero for all intergenerational models; consequently, the c path could not be estimated. The results of these models are summarized in the right columns of Table 3.

Model 1 included the variances of A and E, as well as the paths w, a, and e. The w (w =.130; 95% CI =.059–.200) path indicates that there was a small child-specific effect of marital conflict frequency, such that children who reported more frequent conflict than their siblings were slightly more likely to report conduct problems. The interpretation of the w path is ambiguous, as it can reflect a causal effect of marital conflict exposure on a child’s conduct problems, a reverse causal effect of a child’s behavior problems on exposure to marital conflict, or reporter bias (children reported both on conduct problems and marital conflict). The w path accounted for only 1% of the variance in conduct problems within nuclear families. The small percentage of variance accounted for suggests that the minimal child-specific effect can be attributed to reporter bias. The small magnitude of this effect is consistent with previous research that has found no significant effect of child-specific exposure to marital conflict (Jenkins, Simpson, Dunn, Rosbash, & O’Connor, 2005).

On the between level of Model 1, the estimated a path (a =.295; 95% CI =.004–.587) indicates that the intergenerational relationship between marital conflict and conduct problems may be attributable, at least in part, to genetic factors. The e path, however, was both smaller (e =.098) and not significantly different from zero (95% CI = −.074 to .270), suggesting that direct environmental exposure to marital conflict may play a smaller role in children’s conduct problems. The relative importance of the a and e paths will be better clarified by subsequent model fitting.

To further assess the significance of the a and e paths, the next model dropped the e path and tested the consequent changes in model fit. As can be seen in the indices of model fit in the top of Table 3, dropping the e path in Model 2 resulted in marginal decreases in the BIC and RMSEA. Furthermore, the chi-square difference test (Δχ2 =1.429, Δdf =1) was nonsignificant (p =.232), indicating that the e path could be dropped without detriment to model fit. In other words, the inclusion of the e path did not substantially contribute to the prediction of children’s conduct problems. The a path remained significantly different from zero (a =.387; 95% CI =.103–.671).

Model 3 dropped the a path, which increased the precision with which the e path was estimated (e =.227; 95% CI =.054–.400). Dropping the a path, however, resulted in marginal increases in the AIC and RMSEA compared with Model 1. In addition, the chi-square difference test for Model 3 (Δχ2 = 5.053, Δdf =1) was significant (p =.025), indicating that eliminating the genetic path significantly worsened the fit of the model. The inclusion of the genetic path was important in the prediction of children’s conduct problems. Thus, Model 2 provided the best, most parsimonious fit to the data. In all models, the residual covariance between cousins’ average conduct problems, estimated separately by zygosity was not significantly different from zero.

Overall, twins were very different with respect to the conflict in their marriages, but their children’s conduct problems was predicted better by the genetic liabilities that were common to the twins than by the phenotypic differences between them. The genetic components of marital conflict accounted for about 20% of the total variance in conduct problems between nuclear families.

Discussion

Genetic and Nonshared Environmental Influences on Marital Conflict

Results from our parental models indicate that genetic factors substantially influence marital conflict, consistent with previous work demonstrating genetic influence on marital status, marital satisfaction, and divorce (Jockin et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2004; McGue & Lykken, 1992; Spotts et al., 2004). In contrast, twins’ shared environment, a component that includes demographic and family-of-origin features shared by twins, does not significantly influence marital conflict. Differences between twins, however, account for over half the variance in marital conflict, as might be expected, given that twins have different spouses with whom to argue.

As mentioned previously, there are no genes “for” arguing with one’s spouse. While these results demonstrate that the genotype ultimately influences marital conflict, genetic influences are mediated through more proximate psychosocial variables, such as personality, temperament, or psychopathology. Consequently, the magnitude of genetic influences and “which” genes are involved may be influenced by variables that moderate the relation of proximate psychosocial variables with conflict, such as gender or culture. For example, because marital interactions involve culturally prescribed gender roles, certain personality traits in women may be more strongly associated with marital conflict than in men, just as certain personality traits in women are more strongly associated with divorce than in men (Jockin et al., 1996). To the extent that genetic influences on marital conflict are mediated through personality, the magnitude of genetic influence would differ across genders. Similarly, the psychosocial variables that may mediate the link between genotype and marital conflict in the Australian sample may differ in other nationalities or ethnic groups, as marital conflict is, at least in part, a culturally situated phenomenon.

Genetic Selection in the Intergenerational Association Between Marital Conflict and Conduct Problems

Intergenerational SEMs and a descriptive means analysis suggest that the association between marital conflict and children’s conduct problems is accounted for by children’s inheritance of genetic liabilities common to their psychopathology and their parents’ conflict. There was no association between marital conflict and conduct problems within the children of discordant twin pairs, suggesting that genetic influences shared by twins better predict child conduct problems than twin-specific variables. There was indeed an association between marital conflict and conduct problems within nuclear families; however, the negligible variance in conduct problems accounted for by within-nuclear family variation in exposure to marital conflict, in conjunction with the failure to find a within-twin pair effect, suggests that the child-specific effect reflects reporter bias, rather than a causal effect of conflict on conduct problems or a reverse causal effect of child conduct problems on marital conflict.

It seems likely that, at least to some extent, the genetic factors involved in intergenerational association between marital conflict and child conduct problems are related to parental antisocial behavior. This suggestion is mirrored in the literature on antisocial behavior: children with behavior problems are likely to grow into antisocial adults (Robins, 1966), who then experience high levels of marital conflict (Smith & Farrington, 2004) and pass on their genetic liabilities to the next generation (Slutske et al., 1997).

In addition, the genetic factors involved may confer vulnerability to adverse environmental experiences, such as marital conflict (gene – environment interaction). The present model subsumes genetic differences in vulnerability to environmental risk under genetic main effects, thus considerably oversimplifying the etiology of conduct problems. Moving beyond this oversimplification, however, to a more comprehensive model of the interplay between genetic influences and exposure to marital conflict is no simple task, in part because most existing methods for the analysis of gene – environment interaction entail the assumption that the measured environment is free of genetic influence. As demonstrated in this paper, this is not the case for marital conflict. Eaves and his colleagues (Eaves & Erkanli, 2003; Eaves, Silberg, & Erkanli, 2003) have described Markov Chain Monte Carlo models capable of resolving genetic influences on the likelihood of and vulnerability to environmental experiences. Such models may offer a way forward for future research on the interplay between genetics and aspects of the family environment such as marital conflict.

Methodological Considerations

Limitations in the measurement of marital conflict

Marital conflict is a multidimensional phenomenon, various aspects of which may be related to child adjustment via different processes (Zimet & Jacob, 2001). The present research assessed the frequency of marital conflict, but previous authors have argued that assessing the nature of marital conflict—including the level of hostility, the degree of resolution, and the relevance of the content for the child(ren)—is critical to a comprehensive understanding of the relation between conflict and child adjustment (Goodman, Barfoot, Frye, & Belli, 1999; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992). It is important to note, then, that significant relations between other conflict dimensions and child conduct problems may be evident even after accounting for genetic transmission; our results cannot be generalized beyond marital conflict frequency.

Another limitation of our measurement of marital conflict was our reliance on telephone interviews rather than potentially more reliable methods, such as observation or diaries, which are prohibitively difficult in a sample of this size. We concede that retrospective reports of childhood experiences are problematic, but there is support for our contention that our measurement of marital conflict frequency is adequate. First, prior research has found children’s retrospective reports of family conflict on a single survey item at age 18 to be significantly associated with prior, contemporaneous maternal ratings of family conflict (Henry, Moffitt, Caspi, Langley, & Silva, 1994). Second, the large intraclass correlation among siblings’ reports of marital conflict frequency (.663) indicates that multiple independent adult reporters are converging on a shared report of childhood experience, and decomposition of marital conflict frequency into genetic and environmental components was performed on a latent variable representing that shared experience. Third, despite the large age range of participants, linear and quadratic effects of age predicted <3% of the variance in marital conflict reports. Finally, even with inflated error variance due to a small number of items, our results accounted for over 20% of the between-family variance in children’s conduct problems, an association consistent with effect sizes commonly found in marital conflict research. Future research, however, should examine whether a significant relation between marital conflict and child conduct problems is evident when using more rigorous or reliable measurement strategies.

Limitations in the Children-of-Twins design

The Children-of-Twins design requires extremely large samples in order to have adequate statistical power. Because our statistical power was limited, we did not analyze potential moderators of the association between genetic influences on marital conflict and child conduct problems, such as the gender of the child. For example, genetic liabilities toward affective dysregulation or behavioral disinhibition may be less likely to be expressed as conduct problems in female children than male children because of gender socialization processes. Future research on the effects of marital conflict should examine how moderators such as gender interact with associated genetic liabilities.

In addition, marital conflict is a dyadic phenotype jointly determined by the characteristics of both spouses, whereas shared environmental and genetic influences of only the twin parents are controlled in the present model. The inability to control for genetic influences of the spouses on both marital conflict and on the children of twins complicates the interpretation of results. The power of the Children-of-Twins design to resolve the extent to which intergenerational associations reflects biological inheritance hinges on comparing the correlation of children’s adjustment with parental characteristics and the correlation of children’s adjustment with avuncular characteristics (Eaves, Silberg, & Maes, 2005; Heath et al., 1985; Nance & Corey, 1976). For dyadic phenotypes such as marital conflict, however, the former correlation reflects causation and the genetic influence of both parents, whereas the latter correlation reflects only the genetic influence of the twin parent. Consequently, even when there is a no environmental effect, a within-twin pair association between parental characteristic and child outcome may be evident, leading to false causal conclusions. In other words, the within-twin pair environmental variance may be confounded by the genetic influence of the spouse (Eaves et al., 2005). More relevant to the present results, the reverse situation, in which a true environmental effect is masked by the unmeasured genetic influence of the spouse, is also possible. A masked environmental effect may only arise, however, if the genetic influence of the spouse is in the opposite direction as the environmental effect (i.e., a suppressor effect).

The unresolved questions surrounding how to interpret Children-of-Twins data underscore the conclusion that even sophisticated behavioral genetic designs have limitations. We will never be able to simulate the rigor of randomized experimentation with correlational data. At best, we can think of the nuclear families of twins as a type of matched control group, with which we can test epidemiological associations that are evident when comparing unrelated families. Even with limitations, however, the application of the Children-of-Twins design to the study of marital conflict and its effects on children is a methodological improvement on previous investigations that have been unable to control for any potential genetic confounds.

Future Research

Child-onset versus adolescent-onset conduct problems

Antisocial behavior that begins in childhood and persists throughout development may be considered theoretically and etiologically distinct from antisocial behavior that is limited to adolescence only (Moffitt, 1993). Furthermore, early-onset antisocial behavior is substantially more heritable than adolescent-onset antisocial behavior (Taylor, Iacono, & McGue, 2000). Given this distinction, the processes underlying associations between marital conflict and conduct problems may differ according to the type of antisocial behavior. For example, frequent marital conflict may be related to persistent, early-onset conduct problems primarily through genetic selection effects, while it may be related to adolescence-limited conduct problems primarily through direct environmental causation.

The present research has not differentiated among children with conduct problems according to age of onset because we lack the statistical power to estimate age-of-onset moderation effects. Furthermore, we included children, aged 14–18 years, who had not yet passed through the adolescent risk period for developing antisocial behavior. Those young participants who did not report an earlier childhood history of conduct problems but who later developed adolescent conduct problems were counted as asymptomatic, thus underestimating the rate of adolescent-limited conduct problems in the current sample. The limitations of the current investigation, with regard to power and sample composition, preclude our ability to detect an environmental effect of marital conflict specific to adolescent-limited pathology, but taxonomic distinctions between early-onset and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior suggest that future research consider these separately.

Interparental conflict in nonintact families

Similar to much of the literature on marital conflict, the present study investigated interparental conflict within intact marital relationships only, a restriction that has two critical implications. First, by excluding the families of couples who eventually divorce we may have underestimated the prevalence of severe marital conflict and consequently biased estimates of the relation between conflict and child adjustment, a notable limitation of the current project. Second, the processes underlying the association between conflict and children’s adjustment may differ in nonintact families. Interparental conflict may be more severe in families who eventually divorce and may persist beyond the duration of the marital relationship. Extremely high levels of interparental conflict, experienced in conjunction with parental divorce, may indeed cause poorer adjustment in children, an effect we could not observe in our sample of intact families. In addition, a stronger genetic effect may be evident in nonintact families, as a sample of divorced parents would likely include parents with more severe genetic liabilities for antisocial behavior and other psychopathology. Overall, children in nonintact families experience both heightened environmental stress and inherit greater genetic liabilities than do children in intact families. Future genetically informed research should investigate the relative magnitude of environmental and genetic risks in predicting the adjustment of children in nonintact families.

Conclusions

Our results do not indicate that marital conflict is irrelevant or innocuous in children’s lives. Children’s reactions to their parents’ conflict are demonstrations of distress (El-Sheikh et al., 1989), regardless of whether these reactions solidify into stable, problematic modes of behavior. Marital conflict also increases the likelihood of parental divorce, a disruptive event that is associated with children’s psychopathology within twin pairs (D’Onofrio et al., 2005). Furthermore, our investigation was limited to children’s conduct problems. It remains to be seen whether associations of marital conflict with other forms of maladjustment, such as internalizing or substance use disorders (Emery, 1982), can be replicated using behavior genetic or other quasi-experimental designs.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was funded by grants from the William T. Grant Foundation, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant # AA07535 and AA000264), and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. Initial results were presented at the 2005 SRCD Conference in Atlanta, GA. The authors thank the staff of the Genetic Epidemiology Unit and the Queensland Institute of Medical Research for the data collection, particularly Alison Mackenzie for coordination, as well as the twins and their children for their cooperation. In addition, we thank Bengt and Linda Muthén for helping with the analyses, and Jane Mendle for reviewing and editing previous drafts of this paper.

Contributor Information

K. Paige Harden, University of Virginia.

Eric Turkheimer, University of Virginia.

Robert E. Emery, University of Virginia

Brian M. D’Onofrio, Indiana University

Wendy S. Slutske, University of Missouri

Andrew C. Heath, Washington University

Nicholas G. Martin, Queensland Institute of Medical Research

References

- Amato PR. Explaining the intergenerational transmission of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:628–640. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Rijsdijk FV, Jaffee SR, et al. Strong genetic effects on cross-situational antisocial behaviour among 5-year old children according to mothers, teachers, examiner-observers, and twins’ self-reports. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:832–848. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparauhov T. Weighting for unequal probability of selection in multilevel modeling. 2004. Mplus web notes: No. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Fincham FD, Amir N, Leonard KE. The taxometrics of marriage: Is marital discord categorical? Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechger TM, Boomsma DI, Konig H. A limited dependent variable model for heritability estimation with non-random ascertained samples. Behavior Genetics. 2002;32:145–151. doi: 10.1023/a:1015257908396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Amato PR. Parental predivorce relations and offspring postdivorce well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63:197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JL, Reich T, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies of Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion LA, Goodall G, Rutter M. Behaviour problems in childhood and stressors in early adult life: I. A 20-year follow-up of London school children. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:231–246. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003614x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuer HM, Plomin R, Pedersen NL, McClearn GE, Nesselroade JR. Genetic influence on family environment: The role of personality. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Cloninger CR, Reich T. Clinical assessment: Use of nonphysician interviewers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders. 1978;166:599–606. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197808000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts CA, Nigg JT, Stawicki JA. Family adversity in DSM – IV ADHD combined and inattentive subtypes and associated disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:690–698. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000162582.87710.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM. Coping with background anger in early childhood. Child Development. 1987;58:976–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and marital conflict: The impact of family dispute and resolution. New York: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Johnson JK, Viken RJ, Rose RJ. Testing between-family associations in within-family comparisons. Psychological Science. 2000;11:409–413. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:349–371. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Turkheimer EN, Eaves LJ, Corey LA, Berg K, Solaas MH, et al. The role of the Children of Twins design in elucidating causal relations between parent characteristics and child outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1130–1144. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio B, Turkheimer E, Emery R, Slutske W, Heath A, Madden P, et al. A genetically informed study of marital instability and its association with offspring psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:570–586. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy DL. PhD thesis. University of Queensland; Australia: 1994. Asthma and allergic diseases in Australian twins and their families. [Google Scholar]

- Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Papp LM, Cummings EM. Relations of husbands’ and wives’ dysphoria to marital conflict resolution strategies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:171–183. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Erkanli A. Markov chain Monte Carlo approaches to analysis of genetic and environmental components of human developmental change and G × E interaction. Behavior Genetics. 2003;33:279–299. doi: 10.1023/a:1023446524917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Eysenck HJ, Martin NG. Genes, culture, and personality: An empirical approach. London: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Silberg J, Erkanli A. Resolving multiple epigenetic pathways to adolescent depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1006–1014. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Silberg J, Maes H. Revisiting the children of twins: Can they be used to resolve the environmental effects of dyadic parental treatment on child behavior? Twin Research. 2005;8:283–290. doi: 10.1375/1832427054936736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM, Goetsch VL. Coping with adults’ angry behavior: Behavioral, physiological, and verbal responses in preschoolers. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE. Interparental conflict and the children of the discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin. 1982;92:310–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Waldron M, Kitzmann KM, Aaron J. Delinquent behavior, future divorce or non-marital childbearing, and externalizing behavior among offspring: A 14-year prospective study. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL. A diagnostic interview: The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Grych JH, Osborne LN. Does marital conflict cause child maladjustment? Direction and challenges for longitudinal research. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Eaves LJ, Wormley B, Silberg JS, Maes HH, Kuhn J, et al. Childhood adversity, monoamine oxidase A genotype, and risk for conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:738–744. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Loney BR. Understanding the association between parent and child antisocial behavior. In: McMahon RJ, Peters RD, editors. The effects of parental dysfunction on children. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Barfoot B, Frye AA, Belli AM. Dimensions of marital conflict and children’s social problem-solving skills. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, Bertelsen A. Confirming unexpressed genotypes for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:867–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810100009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]