Abstract

The number of U.S. adults classified as overweight or obese has dramatically increased in the past 25 years resulting in a significant body of research addressing weight loss and weight loss maintenance (WTLM). However, little is known about the potential of WTLM interventions to be translated into actual practice settings. Thus, the purpose of this article is to determine the translation potential of published WTLM intervention studies by determining the extent to which they report information across the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework. A secondary purpose is to provide recommendations for research based upon these findings. To identify relevant research articles, a literature search was conducted using four databases; 19 WTLM intervention studies were identified for inclusion. Each article was evaluated using the RE-AIM Coding Sheet for Publications to determine the extent to which dimensions related to internal and external validity were reported. Approximately half of the articles provided information addressing three RE-AIM dimensions (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, and Implementation), yet only a quarter provided information addressing Adoption and Maintenance. Significant gaps were identified in understanding external validity, and metrics that could facilitate the translation of these interventions from research to practice are presented. Based upon this review, it is unknown how effective WTLM interventions could be in “real-world” situations, such as clinical or community practice settings. Future studies should be planned to address how WTLM intervention programs will be adopted and maintained, with special attention to costs for participants and for program implementation.

Keywords: Weight Loss Maintenance, Translation, RE-AIM

INTRODUCTION

The number of U.S. adults classified as overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2) has dramatically increased in the past 25 years (1–3). Due to the adverse health outcomes associated with obesity (1, 4–6), the body of literature targeting weight loss strategies has abounded yet rates of concomitant weight regain are well documented (7–10). As a result, the need for practical, affordable, and clinically useful intervention strategies that maintain weight loss is paramount (11).

Numerous interventions have included behavioral strategies in clinical trials investigating weight loss maintenance (WTLM), described as an intervention aimed to prevent weight regain following weight loss (11–30). Behavioral strategies associated with successful WTLM include high levels of physical activity (12, 16, 20, 22), self-monitoring of food consumption and body weight (11, 29–31), social and interactive support (13, 14, 17, 21, 29, 30), dietary interventions (18, 19, 27, 28), psychological intervention (23–26) and limiting the amount of time spent watching television (10). Interventions including weight loss medications combined with dietary modification, supplementation with caffeine or protein, prolonged participant contact, problem-solving therapy, and acupressure may also promote WTLM (32). However, the potential for these strategies to be translated into regular community or clinical environments is unknown. The following vignette is used to illustrate this point.

Paula Ellis, MS, RD, is the Director of Wellness for a large manufacturer. She has been asked to develop a worksite weight maintenance program to follow their successful 8-week weight loss program. She found two recent research articles describing 12-month weight loss maintenance interventions, and must decide which approach is best suited to implement for her company’s employees. Program A was tested at a University medical clinic by research assistants; it involved weekly individual counseling sessions and weight checks. This program was effective in maintaining body weight (+/−2.3kg) in 85% of its participants. Program B was tested in an urban YMCA by YMCA staff. The program utilized a printed program training manual and monthly group sessions. About 40% of Program B participants maintained their weight (+/− 2.3kg). Paula decided on Program B because it had a manual, appeared to be fairly successful, and seemed to be more feasible to deliver. However, she felt a bit uncertain with her decision, as Program A had a better success rate.

The purpose of this vignette is not to demonstrate that a program manual makes dissemination of a program easier nor that practitioners should choose the simpler option, even if it is less effective. The purpose is to demonstrate that examining evidence-based interventions from a practice perspective includes the consideration of many factors that are not often reported within the research context. Although there is a growing body of literature addressing methods to maintain weight loss (11, 20, 23, 30, 33, 34), there is relatively little reporting on the potential for these methods to be translated into regular practice settings. Thus, it is not surprising that within the healthcare setting, the process of translating research into evidence-based practice may take 15 to 20 years to occur (35, 36).

This “lag” may be attributed to a lack of reporting on factors important to the audience that would ultimately adopt and implement the intervention (37), and to the linear research production model that emphasizes internal over external validity. Specifically, Flay provides an example of a prevalent scientific of the translational process (38). First, an intervention must undergo an efficacy trial, defined as “tests of whether a … program does more good than harm when delivered under highly controlled and optimum conditions (39)”. Optimal conditions may include screening out less compliant patients (39), thus the generalizability of the interventions tested in an efficacy study is unknown. The next stage in the translation process is an effectiveness trial which “provides tests of whether a…program does more good than harm when delivered under real-world conditions (38).” Effectiveness trials are primarily randomized controlled trials held to the Consolidation of Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) recommendations which emphasize internal validity while only providing modest descriptive recommendations for external validity factors (40) This research model has highlighted the need to focus on translational research and its clinical implications. Translational research is often defined as having two phases: 1) the translation of basic science into clinical research; and 2) how interventions are adopted, implemented, and sustained in a clinical or community setting (41).

Glasgow and colleagues (37, 42–46) have proposed a broader set of metrics and indicators that provide additional information that is needed by practitioners when considering the translation of an evidence-based intervention into routine practice. Specifically, translation of research into practice is best served when studies report more balanced information on internal and external validity. To address this need the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) evaluation framework was developed to provide context for practitioners to consider and compare research-based interventions (37, 42, 46). Importantly, cost is considered a key factor across the five dimensions. The five dimensions can be applied to the evaluation of health behavior interventions and estimate the potential public health impact of interventions and information that can facilitate translation into practice. Definitions and examples reflecting each of these dimensions can be found in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of RE-AIM dimensions with examples found in existing weight loss maintenance literature.

| Dimension | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reach (R) | The proportion and representativeness of individuals willing to participate in a given intervention. | Svetkey, et al. provided a strong Reach component to their research by giving a description of the proposed target population and a detailed description of study participants (i.e., age, weight status, gender, race/ethnicity, and education). Information was provided as to how participants were identified, and a thorough description of inclusion/exclusion criteria (11). |

| Efficacy/effectiveness (E) | The impact of an intervention on important outcomes, including potential negative effects, quality of life, and economic outcomes. | While many studies have a strong Efficacy/effectiveness dimension, Wing, et al. reported many of the dimension’s components, including a thorough explanation of the study design, measures, and results. The article reports imputation and intent to treat procedures, and discusses unintended consequences of the study and attrition (30). |

| Adoption (A) | The proportion and representativeness of locations and intervention staff willing to initiate and adopt an intervention. | Harvey-Berino, et al. described the setting and location of the intervention as well as a description and expertise of the individuals delivering the intervention (14). |

| Implementation (I) | How consistently various elements of an intervention are delivered as intended by intervention staff, and the time and cost of the intervention. | Wing, et al., provides an acceptable Implementation dimension, including information on the number of participant contacts and the timing and duration of contacts. Information was provided on study attendance rates and the percentage of the protocol delivered as intended (29). |

| Maintenance (M) | The extent to which participants make and maintain a behavior change and the sustainability of a program or policy in the setting in which it was intervened. | Leermakers, et al. provided information on Maintenance by assessing their study participants 6 months after the completion of the study. Weight gain and the attrition rate were provided (20). |

The use of the RE-AIM framework may improve the reporting of factors related to external validity and more accurately inform the potential of research to be translated into practice (47). This framework can also provide meaningful information for practitioners. For example, if Paula, from our vignette knew that one of the programs 1) was delivered by someone with her level of training and expertise, 2) had demonstrated effectiveness in a setting similar to her workplace and that the effect was robust across different groups of people, and 3) attracted a large portion of an employee population to participate, cost $3 per employee to implement, and could be sustained with minimal cost to the organization -her choice would have been more informed. Unfortunately, there may be a gap in the literature related to the extent to which WTLM intervention studies report across these dimensions. Thus, the purpose of this article is to determine the translation potential of published WTLM intervention studies by determining the extent to which they report information across the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework. A secondary purpose is to provide recommendations for research based upon these findings.

METHODS

To identify research articles related to WTLM intervention for translation potential, a literature search was conducted using four databases, Medline, PubMed, PSYCinfo, and Ebscohost, using standardized search terms as follows: weight maintenance, long-term weight loss maintenance, effectiveness weight loss maintenance, and efficacy weight loss maintenance. For inclusion, articles must have been published in English, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a long-term weight loss maintenance intervention that included a weight loss trial and > 1 year of intervention, an adult (>17 years old) study population, research conducted after February 1988, and efficacy/effectiveness research. Articles were excluded if they focused on pharmaceuticals, follow-ups, surgery, and weight gain prevention; subsequent articles reporting on the same intervention study were also excluded.

Four-hundred and ninety eight relevant articles were initially identified. Most were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria (n=382). Others were not included due to exclusion criteria (n=96). Nineteen articles met inclusion criteria, and are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Weight Loss Maintenance Intervention Trials: An Evaluation Using RE-AIM Dimensions

| Diet Only Interventions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Reach (R) | Efficacy/Effectiveness (E) | Adoption (A) | Implementation (I) | Maintenance (M) |

| Lantz, et al. 2003 (18) | 18 mo RCT 2 groups (both groups followed a hypocaloric diet minus 500 kcal/day) Intermittent (I): consume VLCD (450kcal/day) for 2 weeks every third month On-demand (OD): consume VLCD when wt increases > 3kg from baseline |

n= 334* 18–60 years old* 247 Female* BMI >30 kg/m2 * |

I lost 7.0kg; OD lost 9.1kg. No significant differences between groups. 65% Attrition* |

Participants were monitored by a physician, registered dietitian, and a nurse at various time points in a clinical setting | Monthly meetings | No data |

| Ryttig, et al. 1995 (28) | 12 mo RCT 2 Groups: Group 1 (G1): hypocaloric diet (1600 kcal/day), of which 220 kcal were provided by a supplement Group 2 (G2): hypocaloric diet (1600 kcal/day), no supplement. |

n= 52 39.1±5.5 years old* 41 Female BMI 39.1±5.5 kg/m2 * |

% wt gain in G1 was 9.3±9.4%: 8.0±8.2kg % wt gain in G2 was 12.3±10.0%: 12.3±9.7kg G1 regained 39± 35.7% of wt lost during weight loss trial compared to 54±38.5% in G2 22% Attrition Effect size: G1–G2: 0.49 |

Interventions and assessments were delivered by a nurse and dietitian in a university outpatient obesity clinic | Both groups were seen for assessments every month for 7 months, then every 7th week during the remainder of the intervention. | No data |

| Diet and Behavior Change Interventions | ||||||

| Study | Study Design | Reach | Efficacy/Effectiveness | Adoption | Implementation | Maintenance |

| Layman, et al. 2009 (19) | 8 mo RCT 2 groups: Low carbohydrate to protein ratio (LOW): 40% energy from carbohydrate, 30% from protein, 30% from fat High carbohydrate to protein (HIGH): 55% of energy from carbohydrate, 15% from protein, 30% from fat |

n= 103 45.4±(SE)1.2 years old* 72 Female* BMI 32.6±(SE)0.8 kg/m2 |

Mean wt change(kg) from baseline: Intent to Treat: LOW: −9.3 ±(SE)1.0 HIGH: −7.4 ±(SE)0.6 Completers: LOW −10.4 ±(SE)1.2 HIGH −8.4 ±(SE)0.9 No difference between groups in mean wt change 31% Attrition Effect size**: LOW-HIGH: 0.31 |

Group meetings were led by a research dietitian at a weight management research facility. Any unexcused absence was followed up by a phone call |

Both groups were required to attend a 1 hour meeting each week. The LOW group had a significantly greater number of participants (64%) complete compared to the HIGH group (45%). Compliance with group meetings was >75%. |

No data |

| Perri, et al. 1988 (24) | 13 mo RCT: 5 groups: Behavior Therapy (B): Control, no maintenance intervention Treatment contact (BC): Therapist contacts with 80 min/wk of exercise recommended BC plus social influence program (BCS): Therapist contacts plus program of social influence strategies BC plus aerobic exercise maintenance program (BCA): Therapist contacts plus aerobic exercise program BC plus aerobic plus social influence (BCAS): Therapist contacts plus aerobic exercise program plus social influence |

n= 94 22–59 years old* 97 Female* |

Wt regain over 13 months for each intervention: B: 7.2kg BC: 1.76kg BCS: 2.91kg BCA: 3.91kg BCAS: 0.13kg 2% Attrition |

Interventions were delivered by a clinical psychologist, physician, or a nurse practitioner | BC, BCS, BCA, and BCAS received 26 biweekly therapist contacts Participants attended 66.8% of the 26 scheduled sessions | No data |

| Ryttig, et al. 1997 (27) | 26 mo RCT 3 Groups: Group 1(A): Hypocaloric diet (1600 kcal) with behavior control modification Group 2(B): Hypocaloric diet (1600 kcal) with behavior control modification with previous wt loss program of VLCD Group 3(C): Hypocaloric diet (1600 kcal) with 239 kcal of a supplement |

n= 77 41.6±10 years old* BMI 37.7±4.8 kg/m2 * |

Mean wt reduction after 26 months was 7%, 10%, and 9.5% in A, B, and C respectively. Mean wt regain for the 3 groups: (A):1.7kg (B): 13.3kg (C): 13.5kg No significant group differences 49% Attrition |

Participants were seen by a nurse if problems arose; group sessions were led by a dietitian. Assessments and groups sessions were held at a hospital obesity unit. |

Four assessment contacts for all groups at months 2, 6, 14, and 26. | No data |

| Physical Activity and Behavior Change Interventions | ||||||

| Study | Study Design | Reach | Efficacy/Effectiveness | Adoption | Implementation | Maintenance |

| Pasman, et al. 1999 (22) | 12 mo non RCT 2 groups: Endurance training (ET): swim, cycle, and run 3–4 per wk Control (C): not involved in a training program |

n= 15 37.3 ±5.2 years old 0 Female BMI 30.9±2.8 kg/m2 |

Wt regain at 12 mo was 65% for the whole group (52% for ET and 74% for the C); no correlation between the training hours per week and the regain of body wt at 12 mo. 3 participants were unwilling to continue the training program, therefore they were moved to a control. |

Weekly endurance training sessions (ET) were monitored by a professional coach at a triathlon club. | ET: 3–4 weekly endurance exercise sessions for 1 hour. | No data |

| Diet, Physical Activity, and Behavior Change Interventions | ||||||

| Study | Study Design | Reach | Efficacy/Effectiveness | Adoption | Implementation | Maintenance |

| Fogelholm, et al. 1999 (12) | 6 mo RCT 3 groups: Control(C): no increase in habitual walking Walk 1 (W1): targeted for 1000 kcal weekly expenditure Walk 2 (W2): targeted for 2000 kcal weekly expenditure |

n= 80 29–46 years old * 80 Female* BMI 34 kg/m2 * Participation rate: 100% |

(C) gained 1.7kg (W1): lost 0.7kg (W2): gained 0.2kg 6% Attrition Effect size: C-W1: 0.52 C-W2: 0.35 W1–W2: 0.19 |

Weekly walking sessions were supervised by an exercise instructor at a clinical institute | All groups included 6 mo of weekly group meetings; W1 and W2 groups had weekly walking sessions | No data |

| Harvey-Berino, et al. 2002 (13) | 12 mo RCT 3 groups: Internet support (IS): biweekly chat sessions, phone calls and emails sent on alternate weeks In-person support (F-IPS): met in-person biweekly for 52 weeks; phone calls or emails sent on alternate weeks Minimal in-person support (M-IPS): met in-person monthly for the first 6 mo, then no contact |

n= 122* 48.4±9.6 years old* 104 Female* BMI 32.2±4.5 kg/m2 * |

IS gained significantly more wt that the F-IPS. No difference between groups at 2-yrs The F-IPS and M-IPS maintained a weight loss ≥ 5% (M-IPS: 81.3%, F-IPS: 81%, IS: 44.4%) 12% Attrition Effect size: IS-MIPS: 0.62 IS-FIPS: 0.78 FIPS-MIPS: 0.00 |

Interventions were delivered by group therapist and peers | IS had biweekly internet sessions, F-IPS had in-person biweekly sessions, and M-IPS met monthly for 1 hour during the first 6 months Attendance to treatment sessions were 59% for F-IPS and 39% for IS Adherence to self-monitoring was 22% for F-IPS and 19% for IS |

No data |

| Harvey-Berino, et al. 2004 (14) | 12 mo RCT 3 groups Internet support (IS): biweekly chat sessions, phone or emails sent on alternate weeks Frequent in-person support (F-IPS): met in-person at an interactive television (ITV) studio biweekly for 52 weeks; phone calls or emails on alternate weeks Minimal in-person support (M-IPS): met in-person over ITV monthly for the first 6 mo, then no contact. IS and F-IPS also participated in a social-influence program |

n= 232 46.0±8.8 years old 194 Female BMI 29.0±4.4 kg/m2 |

No differences in wt loss maintained (8.2% IS, 5.6% F-IPS, 6.0% M-IPS) 24% Attrition Effect size**: IS-MIPS: 0.37 IS-FIPS: 0.26 FIPS-MIPS: 0.05 |

Interventions were delivered by MS-level dietitians over ITV; assessments completed in a clinical university setting | IS had biweekly internet sessions and alternate week phone or email contact, F-IPS had in-person biweekly sessions and alternate week phone or email contact, and M-IPS met monthly for 1 hour during the first 6 months Participants in the F-IPS attended significantly more group meetings compared to those in the IS group (10±5.1 vs. 7.7±5.3 meetings attended) 69% of participants provided data at all assessment points |

No data |

| King, et al. 1989 (16) | 12 mo RCT: 4 groups: Group 1 (1A): telephone and mail contact, previous wt loss through diet only Group 1 (1B): telephone and mail contact, previous wt loss through exercise only Group2 (2A): no contact, previous wt loss through diet only Group 2 (2B): no contact, previous wt loss through exercise only |

n= 90 44.7±7.3 years old 0 Female |

Mean wt changes: 1A: 3.2±2.9 kg 1B: 0.8±3.1 kg 2A: 2.6±2.8 kg 2B:3.9±2.8 kg Greater weight maintenance in 1B compared to 1A, 2A, and 2B. 20% Attrition Effect size: 1A–2A: 0.22 1A–1B: 0.82 1A–2B: 0.25 2A–1B: 0.62 2A–2B: 0.48 1B–2B: 1.07 |

No data | Group 1 received monthly mailings and phone calls lasting 5–10 minutes at months1, 2,3,6,9, and 12. | No data |

| Kumanyika, et al. 2005(17) | 8–18 mo RCT 3 Groups: Group counseling (GC): 6-meetings biweekly then monthly Staff-assisted, self—help (SH): given a self-directed resource kit, monthly calls, facilitator support Clinic visits only (C): no intervention only semiannual clinic visit |

n= 128 45.4±10.2 years old 116 Female BMI 37.0±5.5 kg/m2 |

Weight regain from baseline to final visit: GC: 0.02 (95% CI −1.7, 1.8) SH: 1.1 (95% CI −0.3, 2.5) C: −0.04 (95% CI −1.9,1.8) 32% Attrition |

Counseling and intervention was delivered at a family practice department of a university health system by a nutrition, exercise, or behavior change specialist, of whom 45% were African American. Cost of the program was <$146 per person per year. | GC had 6 biweekly meetings, then met monthly thereafter. Average group session attendance for GC was 40% for the 6 biweekly sessions and 31% for the monthly sessions. In SH, the facilitator completed 35–55% of monthly telephone calls. |

No data |

| Leermakers, et al. 1999 (20) | 6 mo RCT 2 groups: Exercise-focused maintenance (EFM) program: designed to sustain the maintenance of physical activity Wt-focused maintenance (WFM) program: sessions focused on maintenance of wt loss |

n= 67 50.8±11.1 years old 54 Female BMI 30.8±4.5 kg/m2 |

No differences between the 2 conditions in exercise participation and energy expenditure. 15% Attrition Effect size: EFM-WFM: 0.50 |

Groups were led by clinical psychology graduate students | Both groups included 6 months of biweekly group counseling sessions. Participant attendance rates were 73.1% for EFM and 70.8% for WFM | During the 18 month follow-up visit, participants in the WFM group had greater reductions in fat intake and better maintenance of wt loss. 28% Attrition Effect size12–18 months: EFM-WFM: 0.69 Effect size 6–18 month: EFM-WFM: 0.86 |

| Liebbrand and Fichter, 2002 (21) | 18 mo RCT 2 groups: Maintenance (M): supportive weight maintenance program by phone consultation Control (C): no support |

n= 109 37.1±10.8 years old 91 Female BMI 44.8±8.7 kg/m2 |

From baseline-18 mo, BMI increased from 42.54±6.74 to 43±7.81 kg/m2 in the M group and decreased from 40.62±5.67 to 40.58±6.3 kg/m2 in the C group 21% attrition Effect size: M-C: 0.02 |

Interventions were delivered by a psychotherapist; assessments took place at a medical clinic | M received eight 45-minute phone consultations for 9 mo and 4 consultations for the last 9 mo, then invited to a 2-day therapist guided booster session | No data |

| Perri, et al. 2001 (58) | 12 mo RCT: 3 groups: Control (BT): no contact Relapse Prevention therapy (RPT) (7): group sessions for relapse prevention Problem Solving therapy(25): group sessions for problem solving |

n= 80 46.6±8.9 years old* 80 Female* BMI 35.8±4.5 kg/m2 * |

Weight regain from baseline-12 mo: BT: +5.39 kg RPT: +2.56 kg PST: −1.51 kg 28% Attrition Effect size 5–11 month: BT-RPT: 0.94 BT-PST: 1.22 RPT-PST: 0.29 Effect size 11–17 month: BT-RPT: 0.32 BT-PST: 0.57 RPT-PST: 1.0 |

No data | RPT and PST were scheduled for 6 biweekly sessions Audiotape recordings were used to examine protocol delivery. In RPT, 100% of relapse prevention skills were observed and 0% of problem solving skills were observed. In PST, 100% of the problems solving skills were observed and 33% of the relapse prevention skills were observed. Adherence to program goals decreased over time; this differed between BT and PST. |

No data |

| Perri, et al. 2008 (23) | 12 mo RCT 3 groups: Group 1(A): extended care, phone counseling sessions Group1(B): extended care, face to face counseling sessions Group 2 (C): education control group which received newsletters |

n= 234 59.4±6.1 years old 234 Female BMI 36.8±4.9 kg/m2 |

A and B regained less wt than Group C (1.2±(SE)0.7 kg and 1.2±(SE)0.6 kg vs. 3.7±(SE)0.7 kg, and had greater adherence to behavioral weight maintenance strategies. 6% Attrition Effect size: A-B: 0.00 A–C: 0.42 B–C: 0.43 |

Participant contacts were led by Cooperative Extension Services (CES) agents with a BS or MS in nutrition, exercise physiology, or psychology; in rural CES offices. Costs to program (per participant): A: $192±21 B: $391±73 C: $116±19 Costs to participant: A: $1933±1436 B: $2157±1449 C: $1708±1692 |

A and B received 26 biweekly counseling sessions, A received 15-20 min sessions and B received 60 min sessions. C received 26 biweekly mail newsletters. Sessions were based on Perri’s 5-stage problem solving model(25). A and B’s mean number of sessions attended were 13.8±8.6 and 21.1±5.7, respectively. |

No data |

| Riebe, et al. 2004 (26) | 18 mo RCT 2 Groups: Extended care group (EC): received additional personalized Transtheoretical. Model reports Control (C): received generic materials about diet/exercise. Both groups received reports on anthropometrics, biochemical, and dietary intake |

n= 144 50.2 ±9.2 years old BMI 32.5±3.8 kg/m2 |

Mean wt change from baseline-24 mo: EC: 87.6±15.9 kg to 90.5±16.9 kg C: 84.1±14.1 kg to 86.9±15.4 kg No significant differences in wt change between groups. |

A registered dietitian reviewed food records.* | Both groups received mailed reports at 6 and 18 mo, EC received mailed reports based on the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change at mo 3 and 9. | Both groups were received a follow up assessment at 18 months. 32% Attrition |

| Svetkey et al. 2008 (11) | 30 mo RCT 3 groups: Personal contact (PC): monthly telephone and every 4th month face-to-face counseling Interactive technology-based intervention: participants were encouraged to regularly log on to an interactive Web site Self-directed (control)(25): minimal intervention |

n= 1032 55.6±8.7 years old 654 Female BMI 34.1±4.8 kg/m2 |

PC regained 4.0kg ITI regained 5.2kg SD regained 5.5kg 71% of study participants remained below entry weight PC regained less wt as compared to SD. No difference between PC and ITI 6.6% Attrition Effect size: SD-ITI: 0.05 SD-PC: 0.27 PC-ITI: 0.27 |

Clinical university setting | 30 monthly contacts for PC group, duration of 5–15 min each, and every 4th month duration was 45–60 min. | No data |

| Wing, et al. 1996 (29) |

Study 1:12 mo RCT 2 Groups: Group 1 (G1): telephone-assisted weight maintenance and access to a nutritionist for further counseling Group 2 (G2): no-contact |

n= 53 43.6± (SE)1.5 years old 53 Female BMI 32.2±(SE)0.4 kg/m2 |

G1 had a wt gain of 3.9± (SE)1.1kg vs a wt gain of 5.6±(SE)1.0kg in G2 15% Attrition Effect size: G1–G2: 0.33 |

Phone calls were completed by a trained interviewer in a university clinic | Participants were called every week for 15 min for the duration of the study; 80% of the calls were completed. 92% of participants were able to self report weight, 58% self reported food logs, and 62% self reported exercise logs. |

No data |

| Wing, et al. 1996 (29) |

Study 2:12 mo RCT Group 1 (G1): could purchase food boxes during any 4 months of program Group 2 (G12): no food provisions |

n= 48 40.7± (SE)1.5 years old 48 Female BMI 32.4±(SE)0.4 kg/m2 |

G1 had a wt gain of 4.2± (SE)1.0kg vs a wt gain of 4.3±(SE)1.1kg in G2 Only 12 participants ordered food provisions. 0% Attrition Effect size: G1–G2: 0.02 |

Participants were weighed and discussed problems with a therapist. | Both groups were seen monthly for group sessions for the duration of the study. | No data |

Represents data from the weight loss phase. No data were provided for only the weight maintenance phase of the intervention.

Effect size calculated from the mean (± SD) of the change in weight (kg) from baseline of weight loss phase to post intervention of weight maintenance phase. No data was reported for weight change from baseline of weight maintenance phase to post intervention of weight maintenance phase.

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; min, minute; mo, month; RCT, Randomized Control Trial; VLCD; very low calorie diet; wt, Weight.

Data are reported as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

The RE-AIM Coding Sheet for Publications

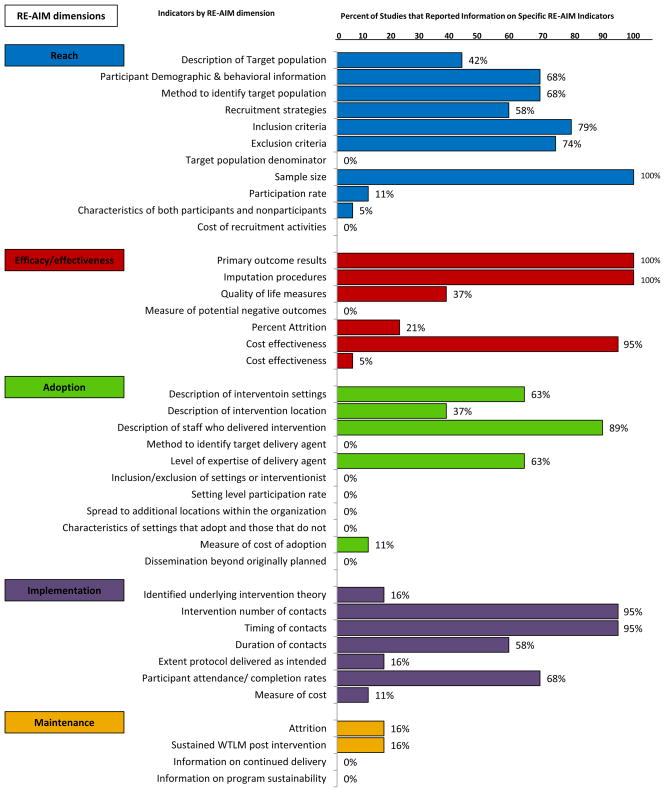

To evaluate the translation potential of WTLM studies, we utilized the RE-AIM Coding Sheet for Publications (48). The Coding Sheet includes a series of “yes” or “no” questions for indicators within each of the five RE-AIM dimensions. The Coding Sheet is available as an online supplementary Figure. Each study was coded by two of the three authors and results were compiled into a spreadsheet, reported graphically in the Figure. A Cohen’s Kappa was used as a measure of agreement between the reviewers (49). Discrepancies were discussed by all three authors and consensus was achieved across reviewed studies.

Figure.

RE-AIM* dimensions and individual indicators using the RE-AIM Coding Sheet to identify “gaps” in existing weight loss maintenance interventions

*RE-AIM: Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance

The coding sheet (see supplementary online Figure) includes six sections: article characteristics, reach, efficacy/effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. The original coding sheet was revised for the present analysis, to include refinements of RE-AIM information (45).

Specific details of the coding process are as follows. For the “demographic and behavioral information” question, “yes” was coded only if the study included gender, age, social economic status, and race. For the question “described target population”, “yes” was coded only if the study described a specific population being targeted for intervention (e.g. intervention specifically targeted overweight or obese African American females in urban Richmond, Virginia) and not just the individuals who were enrolled (e.g., the study sample was 50% African American). For the question on reporting of the theoretical basis of the intervention, “yes” was coded only if an evidence-based theoretical model or construct was utilized (e.g. transtheoretical model, self-efficacy). With respect to “participation rate” on the coding sheet, two participation levels were identified (37, 50). Level 1 participation rate was calculated based on the sample size divided by the total number of individuals projected in the target population. Level 2 participation rate was calculated based on the sample size divided by the number of individuals who were either exposed to, or responded to, recruitment efforts (37). As there was little reporting of Level 1 participation rate, any study that reported Level 2 rates was coded as providing information on Reach.

Statistical Analysis

Standardized effect sizes d=(x1−x2)/pooled standard deviation were calculated (51) across studies with x1−x2 representing mean change in weight (kg) from baseline weight maintenance to post-intervention weight maintenance. All RE-AIM coding was evaluated across raters using Cohen’s Kappa (49) and the findings were summarized and presented in percents. Percents were computed at two levels. First, the proportion of indicators reported within each RE-AIM dimension was computed (i.e., number of indicators reported for a given dimension divided by the total number of possible indicators within the dimension). Second, the proportion of studies that reported specific indicators within each RE-AIM dimension was computed (i.e., number of studies that reported divided by total number of studies). These methods are similar to that recommended for analysis of the RE-AIM metrics (37, 52)

RESULTS

Scoring of the articles resulted in a substantial agreement between raters, k=0.83 (±0.20), with the range −0.25 (±0.02) to 0.89 (±0.04) between the RE-AIM dimensions. The mean effect size of the scored articles was d = 0.38 (±0.05), with effect sizes ranging from 0.00 to 1.22. Details of the 19 studies reviewed, according to RE-AIM dimension, and categorized by intervention type (i.e., diet-only; diet and behavior change; physical activity and behavior change; or diet, physical activity, and behavior change) are presented in the Table 2. While half of the articles provided information addressing three RE-AIM dimensions (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, and Implementation), few reported information addressing Adoption and Maintenance (see Figure). Results across RE-AIM dimensions are summarized as follows:

Reach

Only seven (37%) articles reported more than 50% of the Reach indicators with the top two indicators reported being sample size (100%) and inclusion criteria (79%). The median number of participants was 103 and only 2 studies reported participation rates (78% & 100%). Finally, only one study reported on the representativeness of the study participants relative to the target population. No articles reported cost of recruitment or target population denominator.

Effectiveness/efficacy

Fifty-one percent of the Effectiveness/efficacy indicators were reported across WTLM studies with the top three indicators being measures used (100%), results (100%), and percent attrition (95%). Median attrition rates across follow-ups were 21%. While a small proportion of the studies reported tracking unintended or negative consequences (21% reporting) and cost effectiveness (5%), no articles reported on quality of life. Of the studies reviewed, the most effective WTLM interventions were group-based behavioral treatments (relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy) (25) and telephone and mail personal information contacts with individuals that had previously lost weight through an exercise-only intervention (16). The average duration of the weight maintenance intervention was 12.6 months; weight regain was more likely reported with interventions including only hypocaloric diets and supplements after a very low calorie diet (VLCD) weight loss trial (27, 28). In addition, the highest attrition (65%) was reported in a VLCD trial (18).

Adoption

Only about one-fourth of the Adoption indicators were reported, with most studies reporting a description of staff who delivered the intervention (89%). Only six studies reported using Registered Dietitians as intervention delivery personnel. No articles reported methods used to identify target delivery agent, inclusion/exclusion of settings or interventionist, rate of participation, organizational spread, characteristics of adoption/non adoption, or dissemination.

Implementation

Along with Effectiveness, this RE-AIM dimension was most frequently reported across studies reviewed. More than 59% of Implementation indicators were coded with the top two indicators reported being intervention number (95%) and timing of participant contacts (95%). The least likely to be reported in this sample were measures of cost, theoretical constructs used as the basis of intervention, and extent of the protocol that was delivered as intended.

Maintenance

This RE-AIM dimension was least frequently reported throughout the sample representing 7.9% of the Maintenance indicators. Only three articles (16%) addressed any indicators in the Maintenance dimension; they were behaviors assessed after the completion of the WTLM intervention (16%) and percent attrition at that assessment (16%).

CONCLUSIONS

The field of inquiry within WTLM is a vibrant research area that could have significantly impact population health. However, within the context of attempting to develop WTLM interventions that have the potential for translation into regular practice, it is critical to address, evaluate, and understand the extent to which interventions have the potential to reach a large proportion of the target population, be effective, align with the available delivery system resources, and be sustainable (53). This analysis, as well as others (32, 33), identified numerous effective WTLM interventions. However, in contrast to previous reviews in this area, we have identified significant gaps in important factors related to external validity (e.g. costs, adoption, representativeness) and metrics that could facilitate the translation research interventions to practice settings. To date, it remains largely unknown how effective WTLM interventions are in “real-world” situations, such as clinical or community practice settings.

Often behavioral interventions do not reach those who could benefit most, they show reduced effectiveness over time, and they do not address setting-related issues necessary to ensure institutionalization and sustainability of content delivery at the organizational level (37). It is uncertain if WTLM intervention research suffers from these same limitations, yet these findings confirm that the reporting of external validity information is greatly lacking. Of all of the studies reviewed, the one reporting the most information across RE-AIM dimensions still reported only about half of the indicators evaluated in this review (17). While the study provided an exceptionally detailed overview of Reach, Efficacy, and Implementation, there was still little information provided on potential adoption or sustainability.

In comparison to other reviews based on the RE-AIM framework, the WTLM literature is remarkably consistent (37, 52, 54–56). Specifically, we found that only 5% of studies on WTLM reported on participant representativeness. This finding is consistent with the gap in the literature on general physical activity, nutrition and smoking cessation interventions (i.e., 14% of studies reported representativeness (37)), physical activity interventions for cancer survivors (i.e., no studies reported (52)), and interventions to prevent childhood obesity (i.e., 10% of studies reporting (56)). It is also of note that the proportion of WTLM trials that reported on quality of life outcomes (i.e., no studies reported in our review) is similar to proportion found in a review of 119 studies on physical activity, nutrition and smoking cessation across school, community, health care, and work site settings (i.e., 7% of studies reported on quality of life (37)). In contrast, about a third of the studies examining the prevention of childhood obesity report on quality of life outcomes (56).

Also, missing across the extant literature represented across RE-AIM reviews is consistent reporting of setting level representativeness, cost, setting level maintenance, and—to a lesser extent—the reporting of the degree to which an intervention is delivered as intended. Indeed, no studies in our review and only two studies across other RE-AIM reviews (37, 56) report on setting level representativeness and potential for maintenance. Eleven percent of the studies in our review reported on cost issues. This suggests that compared to other physical activity, nutrition, and smoking cessation trials that the WTLM literature has a lower attendance to cost. Glasgow and associates found about one third of the studies they reviewed includes some information on cost (37). Finally, the WTLM literature seems to be less likely to report on the degree to which an intervention is delivered as intended (i.e., about 16% of studies) when compared to other reviews that, on average, over half of the studies reviewed contained such information (37, 52, 54–56).

Based on this evaluation and others (37, 43, 47, 57, 58), a number of recommendations may be considered for future WTLM research to better align with the RE-AIM framework:

Reach

Only sample size was reported with unanimous consistency across studies and reach dimensions. No study provided a denominator from which to calculate proportional reach. When participation rate was calculated it was typically done so as a proportion of people who follow-up on the advertisements, who ultimately were eligible, and enrolled in the study. When reporting on the reach of an intervention, it is recommended that authors provide a brief definition of the intended population and a proportional value that reflects the penetration of the intervention into the target population. For most efficacy trials the concern is recruiting enough participants to provide the necessary power to detect changes between groups; yet understanding the number of potential participants that were exposed to recruitment materials can provide a rough estimate of the likely reach the program will achieve. Collecting demographic information on both those who agree to participate and those who decline participation would provide information on subgroups within the population who may not be represented in the study sample.

Efficacy/effectiveness

While all studies reported intervention outcomes, no study examined quality of life, 42% used intent to treat analyses rather than present at follow-up. Understanding quality of life in response to WTLM interventions could provide information that can be used to enhance participant engagement, or to determine if a given intervention is successful in maintaining weight loss maintenance but also influences quality of life.

Adoption

Few effectiveness trials have been conducted to achieve WTLM; that is, efficacy trials are prevalent. Thus it is not surprising that adoption indicators are almost exclusively absent beyond describing where the study is taking place and the intervention staff who deliver the program. As only 23% of the adoption indicators were coded across WTLM studies, an increased focus on balanced reporting of internal vs. external validity indicators would provide meaningful information related to the applicability of a given intervention across settings and those delivering the interventions. Information on why certain delivery locations and staff were selected should also be presented.

Implementation

Intervention contact and duration was frequently reported, and ~ 73% (n=14) of studies reported participant adherence to sessions. In contrast, only 1 in 5 studies reported the underlying theoretical approach to intervention development. As theory provides an understanding of the principles by which an intervention is thought to achieve its effect (53), the specific theory or theoretical constructs used in the intervention should be reported. The extent to which the intervention was delivered as intended should also be included.

Maintenance

In spite of the research focus on wei ght maintenance, WTLM studies did not often report on the sustainability of effects once the intervention was complete, attrition, or potential for the programs to be sustained in regular practice. This issue would be of significant interest to practitioners. Thus, it would be beneficial for WTLM research studies to include follow-up assessments after the intervention is complete, to determine the sustainability of weight loss maintenance and other lifestyle behaviors beyond the actual intervention period.

Cost

Measures of cost of recruitment and effect iveness were absent within the reviewed literature, and <10% of the articles reviewed examined cost of implementation or adoption. We acknowledge that modeling costs across the RE-AIM dimensions is a field of scientific inquiry in and of itself. However, it is possible for researchers to track costs and report the figures within their work (See (23) for an excellent example). Understanding the cost of an intervention across these dimensions would likely also be highly valued in the practice setting. Thus, study protocols should assess costs across the research process from recruitment through the implementation process, and include this data when reporting intervention effects.

For practitioners such as Paula depicted in our vignette, the internal as well as the external validity in studies should be evaluated to determine the most appropriate WTLM intervention for a particular practice setting. Examining research and selecting interventions that include a broad heterogenous sample and defined population, consideration of program delivery personnel, costs, and a feasible intervention design will increase likelihood of success when attempting to translate programs into clinical and community settings.

The need to translate successful WTLM interventions into practice is clear. The National Institutes of Health has numerous grant opportunities for funding and planning of translational research, including research addressing WTLM. Specific to WTLM research, future projects should be planned to address how the program will be adopted and maintained with special attention to costs related to participants and program implementation, which were identified as limitations in current WTLM literature. Translational research addressing these limitations will begin to bridge the gaps between long-term WTLM research and practice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeremy D. Akers, Email: jdakers@vt.edu, Virginia Tech, 228 War Memorial Hall (0351), Blacksburg, VA 24061, Phone: (540) 231–6469.

Paul A. Estabrooks, Email: estabrkp@vt.edu, Virginia Tech, VT Riverside, 1 Riverside Circle SW, Suite 104, Roanoke, VA 24016, Phone: (540) 857–6664.

Brenda M. Davy, Email: bdavy@vt.edu, Virginia Tech, 221 Wallace Hall (0430), Blacksburg, VA 24061, Phone: (540) 231–6784, Fax: (540) 231–3916.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odgen CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, Flegal KM. NCHS data brief no. 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Obesity among adults in the United States—no statistically significant change since 2003–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein S, Burke LE, Bray GA, Blair SE, David B, Pi-Sunyer X, Hong Y, Eckel RH. Clinical implications of obesity with specific focus on cardiovascular disease: A statement for professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2004;110(18):2952–2967. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145546.97738.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poirier PG, Thomas D, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer XF, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease From the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; US Government Printing Office, Public Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffery RW, Epstein LH, Wilson TG, Drewnowski A, Stunkard AJ, Wing RR. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassirer JP, Angell M. Losing weight--an ill-fated New Year’s resolution. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:52–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801013380109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasman WJ, Saris WH, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Predictors of weight maintenance. Obes Res. 1999;7:43–50. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:222S–225. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, Vollmer WM, Gullion CM, Funk K, Smith P, Samuel-Hodge C, Myers V, Lien LF, Laferriere D, Kennedy B, Jerome GJ, Heinith F, Harsha DW, Evans P, Erlinger TP, Dalcin AT, Coughlin J, Charleston J, Champagne CM, Bauck A, Ard JD, Aicher K. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: The weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Oja P. Eating control and physical activity as determinants of short-term weight maintenance after a very-low-calorie diet among obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(2):203–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, DiGiulio M, Gold EC, Moldovan C, Ramirez E. Does using the Internet facilitate the maintenance of weight loss? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(9):1254–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, Gold EC. Effect of Internet support on the long-term maintenance of weight loss. Obesity. 2004;12(2):320–329. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arc Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AC, Frey-Hewitt B, Dreon DM, Wood PD. Diet vs exercise in weight maintenance. The effects of minimal intervention strategies on long-term outcomes in men. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(12):2741–2746. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.12.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumanyika SK, Shults J, Fassbender J, Van Horn L, Perri MG, Czajkowski SM, Schron E. Outpatient weight management in African-Americans: the Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Program (HELP) study. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):488–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lantz H, Peltonen M, Agren L, Torgerson JS. Intermittent versus on-demand use of a very low calorie diet: a randomized 2-year clinical trial. J Intern Med. 2003;253(4):463–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layman DK, Evans EM, Erickson D, Seyler J, Weber J, Bagshaw D, Griel A, Psota T, Kris-Etherton P. A moderate-protein diet produces sustained weight loss and long-term changes in body composition and blood lipids in obese adults. J Nutr. 2009;139(3):514–521. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.099440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leermakers EA, Perri MG, Shigaki CL, Fuller PR. Effects of exercise-focused versus weight-focused maintenance programs on the management of obesity. Addict Behav. 1999;24(2):219–227. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibbrand R, Fichter MM. Maintenance of weight loss after obesity treatment: is continuous support necessary? Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(11):1275–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasman WJ, Saris WH, Muls E, Vansant G, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Effect of exercise training on long-term weight maintenance in weight-reduced men. Metabolism: Clinical And Experimental. 1999;48:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, Dale MS, Daniels MJ, Radcliff TA, Martin AD. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Inter Med. 2008;168(21):2347–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perri MG, McAllister DA, Gange JJ, Jordan RC, McAdoo G, Nezu AM. Effects of four maintenance programs on the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(4):529–534. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(4):722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riebe D, Blissmer B, Greene G, Caldwell M, Ruggiero L, Stillwell KM, Nigg CR. Long-term maintenance of exercise and healthy eating behaviors in overweight adults. Prev Med. 2005;40(6):769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryttig KR, Flaten H, Rossner S. Long-term effects of a very low calorie diet (Nutrilett) in obesity treatment. A prospective, randomized, comparison between VLCD and a hypocaloric diet+behavior modification and their combination. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21(7):574–579. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryttig KR, Rossner S. Weight maintenance after a very low calorie diet (VLCD) weight reduction period and the effects of VLCD supplementation. A prospective, randomized, comparative, controlled long-term trial. J Intern Med. 1995;238(4):299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Burton LR, Hellerstedt WL. Effect of frequent phone contacts and Optional Food Provision on maintenance of weight loss. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(3):172–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02883394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turk MW, Yang K, Hravnak M, Sereika SM, Ewing LJ, Burke LE. Randomized clinical trials of weight loss maintenance: A review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24(1):58–80. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317471.58048.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74(5):579–584. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine MD, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, Wing RR, Weissfeld L, Qin L, Marcus MD. Weight gain prevention among women. Obesity. 2007;15(5):1267–1277. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balas EA, Borren BS. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray AT, editors. Yearbook of Medical Informatics. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. pp. 65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks PA. The future of health behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(1):3–12. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flay BR, Phil D. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Prev Med. 1986;15:451–474. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasgow RE, Magid DJ, Beck A, Ritzwoller D, Estabrooks PA. Practical clinical trials for translating research to practice: design and measurement recommendations. Med Care. 2005;43(6):551–557. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163645.41407.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasgow RE. Translating Research to Practice: Lessons learned, areas for improvement, and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2451–2456. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glasgow RE. eHealth evaluation and dissemination research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(suppl 5):S119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Vogt TM. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):688–694. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. The future of physical activity behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(2):57–63. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. [Accessed March 22, 2009.];RE-AIM Website. http://www.re-aim.org/

- 49.Landis RJ, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:671–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status? Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:100–104. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 52.White SM, McAuley E, Estabrooks PA, Courneya KS. Translating physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors into practice: an evaluation of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9084-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Estabrooks P, Glasgow RE, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical activity promotion through primary care. JAMA. 2003;289:2913–2916. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dzewaltowski DA. Emerging technology, physical activity, and sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Rev. 2008;36:171–172. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31818784ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glasgow RE. What types of evidence are most needed to advance behavioral medicine? Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE. Review of external validity reporting in childhood obesity prevention research. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bull SS, Gillette C, Glasgow RE, Estabrooks PA. Work site health promotion research: to what extent can we generalize the results and what is needed to translate research to practice? Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:537–549. doi: 10.1177/1090198103254340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perri MG, Nezu AM, Viegener BJ. Improving the long-term management of obesity: Theory, research and clinical guidelines. New York: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]