Abstract

The subventricular zone (SVZ) is a continual source of neural progenitors throughout adulthood. Many of the animal models designed to study the migration of these cells from the ventricle to places of interest like the olfactory bulb or an injury site require histology to localize precursor cells. Here, it is demonstrated that up to 30% of the neural progenitors that migrate along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) in an adult rodent can be labeled for MRI via intraventricular injection of micron sized particles of iron oxide (MPIOs). The precursors migrating from the SVZ along the RMS were found to populate the olfactory bulb with all three types of neural cells; neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes. In all cases 10-30% of these cells were labeled in the RMS en route to the olfactory bulb. Ara-C an anti-mitotic agent eliminated precursor cells at the SVZ, RMS, and olfactory bulb and also eliminated the MRI detection of the precursors. This indicates that MRI signal detected is due to progenitor cells that leave the SVZ and is not due to non-specific diffusion of MPIOs. Using MRI to visualize neural progenitor cell behavior in individual animals during plasticity or disease models should be a useful tool, especially in combination with other information that MRI can supply.

Introduction

In rodents there are two areas of the brain that are widely believed to be a source of neurogenesis into adulthood, the hippocampus and the subventricular zone (SVZ); for a review see Abrous (Abrous et al., 2005). The SVZ is the largest source of progenitors in the brain. Progenitors formed in the SVZ migrate rostrally along a well defined pathway known as the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to the olfactory bulb where they differentiate into neurons (Doetsch and AlvarezBuylla, 1996; Gotts and Chesselet, 2005). The astroglial progenitors, type B cells, that reside in the SVZ have been shown to self replicate as well as give rise to migrating neurons (Gritti et al., 2002), and can also give rise to both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Levison and Goldman, 1993). In addition, it was recently reported that the SVZ is not only the originator of new neurons in the olfactory bulb but oligodendrocytes as well (Menn et al., 2006). Neurogenesis in the SVZ has been shown to have the potential for being utilized in neural repair after acute brain injury (Cayre et al., 2006; Gotts and Chesselet, 2005). However, most of the research with neural progenitor migration relies on ex vivo processing of tissue, limiting the ability to study the whole brain of a live animal.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a unique tool that has been used to noninvasively observe cell trafficking in vivo, for a review see Frank et al (Frank et al., 2004), Bulte and Kraitchman (Bulte and Kraitchman, 2004), and Ho and Hitchens (Ho and Hitchens, 2004). Iron oxide particles are commonly used as the contrast agent for cell tracking studies as they provide a strong and characteristic hypointense signal in T2 and T2* weighted MRI. Iron oxide particles can be endocytosed by a variety of cell types (Bulte et al., 1999; Modo et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 2004). A large amount of effort has gone into developing techniques that enable loading of cells with sufficient iron oxide to enable detection by MRI, usually with small nano-sized particles. Recently, it has been shown that micron sized particles of iron oxide (MPIOs) can give sufficient loading of cells for MRI and only a single particle is required for detection (Shapiro et al., 2006; Shapiro et al., 2005). This allowed for the possibility of labeling cells for MRI in cases when there will be inefficient endocytosis of the particles. For example, work done by Shapiro et al (Shapiro et al., 2006) demonstrated that endogenous neural progenitors could be labeled with MPIOs by direct injection into the ventricles near the SVZ. Even though there was inefficient uptake of MPIOs by precursors in the SVZ they could still be detected by MRI migrating along the RMS to the olfactory bulb. It was demonstrated that MPIOs were intracellular; however, it was assumed that migrating cells were essential to transport the contrast agent. It is possible that MPIOs could travel along the RMS and then be endocytosed locally by cells. Furthermore, there was no quantitation of the types and percent of cells that were labeled by the direct injection strategy. Here we report on using MPIOs to label the endogenous neural progenitors and demonstrate that inhibiting cell proliferation, thus migration to the olfactory bulb, also prevents MPIO movement to the olfactory bulb. We also illustrate that the SVZ can populate the olfactory bulb with MPIO+ neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes, confirming the SVZ as a source of neurogenesis in the adult rat. Finally, the percent of different cell types labeled in different brain areas is quantified.

Materials and Methods

Animal MPIO injections and Ara-C infusions

Eighteen, 6 week old Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA) were stereotactically injected with 1.4×108 MPIOs (50 μL). The 1.63 μm diameter polystyrene particles with carboxyl functional groups were purchased commercially (Bangs Laboratories, Inc., Fishers, IN). A FITC derivative, Dragon Green (Ex: 488 nm, Em: 520 nm) came encapsulated with the iron oxide in a styrene shell. The MPIOs were 45% iron oxide. Based on work by Shapiro et al (Shapiro et al., 2006), the injection coordinates into the lateral ventricle were 2 mm caudal and 2 mm medial to bregma, and 3 mm ventral from the dura. It was critical to inject into the ventricle near the SVZ. Other injection sites in the lateral ventricle from the SVZ did not lead to efficient labeling (data not shown). Immediately after injection, ALZET mini-osmotic pumps (Durect Co., Cupertino, CA) were used to deliver an anti-mitotic agent, Ara-C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), to a cannula placed at the injection site. The pump delivered 4% Ara-C continually for 2 weeks at a rate of 0.5 μL/hr. This procedure was performed on 9 animals and served as a control to inhibit neural progenitor migration. After 2 weeks, the pump was removed and the animals were imaged. Six animals were injected with MPIOs and had no Ara-C were also imaged every 2 weeks. Three other animals were scanned that contained no MPIOs or had Ara-C infused. All the experiments with animals were in compliance with protocols approved by the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Animal Care and Use Committee.

MRI

MRI data was acquired on an 11.7 T animal MRI system (30 cm 11.7 T horizontal magnet, Magnex Scientific, Oxford, England, MRI Electronics, Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA, and 9 cm 3 gradient shims, Resonance Research Inc, Billerica, MA) using a custom built volume transmit coil and a custom built, 2.5 cm diameter, receive-only surface-coil. Most MRI was performed two weeks post injection. Animals were placed in a MRI compatible cradle with a stereotactic head-frame under continual anesthesia of 2-3% isoflurane in 75% O2/25% medical air. Animals were orally intubated and mechanically ventilated at 66 breaths/min while the end tidal CO2 and respiration patterns were monitored. Body temperature was maintained at 37° C using a rectal thermometer feedback probe and a circulating water bath. Flash 3D gradient echo sequences were used for all MRI acquisitions with the following parameters: FOV 2.56 cm3 or 1.92 cm2, matrix 2563 (100 μm or 75 μm isotropic resolution), 12.5 kHz bandwidth, TE 8 ms, and TR 30 ms.

Histology

Following the MRI acquisitions, animals were transcardially perfused with PBS followed with 10% formalin. Brains were removed with the olfactory bulbs attached and stored in the same 10% formalin solution for at least 6 hr. Brains were then placed in a 30% sucrose solution for 2-3 days. Tissues were processed for frozen sections (Histoserv, Inc, Germantown, MD). Serial 16 μm sagittal sections were cut that included the olfactory bulb, RMS, and SVZ. Histology sections were rinsed 2× with either normal physiological medium (NPM) or DPSS. Extracellular primary antibodies were applied to sections in either NPM with 1% BSA or DPSS with 1% BSA for 1 hr at 25° C. A list of primary antibodies used for the IHC is shown in Table 1. Primary antibodies included anti-vimentin, anti-PSA-NCAM (polysialic acid-neural cell adhesion molecule), anti-Tuj 1, anti-GFAP, anti-Jones (Sigma-Aldirch, St. Louis, MO), anti-MAP2, anti-O4, and anti-PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen). All primary antibodies were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) and diluted 1/100 unless otherwise stated. The sections were washed 3× with NPM or DPSS. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Cy5.5, or Cy3 conjugated (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After extracellular antibody procedures the slides were soaked in 4% paraformaldehye, rinsed 3× with PBS, and incubated with 70% ethanol for 20 min. The intracellular antibodies were then applied the same way as the extracellular markers. Fluorescence images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Germany) or an Olympus IX71 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA).

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies used in the experiments.

| Antibody | Background | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Polysialic acid-Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (PSA-NCAM) | A surface glycoprotein. Expressed on migrating neural progenitor cells. | (Hu et al., 1996) |

| Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) | Protein expressed during DNA synthesis. | (Belvindrah et al., 2002) |

| Vimentin | An intermediate filament protein. Expressed in neural progenitor cells. | (Zerlin et al., 1995) |

| CDw60 (Jones) | A surface ganglioside carbohydrate. Expressed in migrating neural progenitors. | (Mendez-Otero and Cavalcante, 1996) |

| β-Tubulin III (Tuj 1) | Microtubule expressed in neurons. | (Abrous et al., 2005) |

| O4 | Reacts with a surface galactosylcerebroside carbohydrate on oligodendrocytes. | (Menn et al., 2006) |

| Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) | Proteins expressed by neurons. | (Yu et al., 2006) |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | An intermediated filament protein expressed in astrocytes. | (Abrous et al., 2005) |

| Integrin αM (OX42) | Surface receptor on microglia. | (Chugani et al., 1991) |

MACS and FACS Analysis

Animals were decapitated under anesthesia and their brains removed. The SVZ, RMS, and olfactory bulbs were dissected from the brain and separated. The tissue samples were minced then placed in 20 U/mg papain (Worthington Biochemical Co., Lakewood, N.J) at 37° C for 1 hr. Cells were then isolated using a 10%/20%/60% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) gradient. For magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS), miniMACS™ columns (Mitenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) were used to isolate cells labeled with MPIOs. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and the immunocytochemistry (ICC) procedures were the same as for the immunohistochemistry (IHC) discussed above. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) procedures are discussed in detail in Maric et al (Maric and Barker, 2004). Primary antibodies for FACS analysis included anti-GFAP, anti-O4, anti-Tuj 1, and anti-OX42 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Flour conjugated (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Results

Neuroblast migration and inhibition with Ara-C

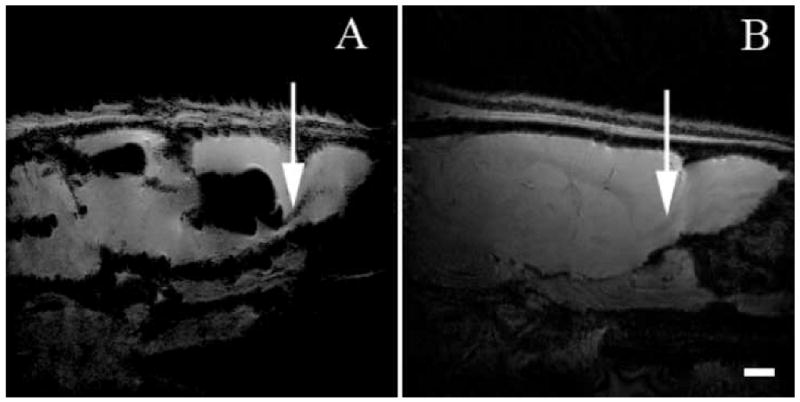

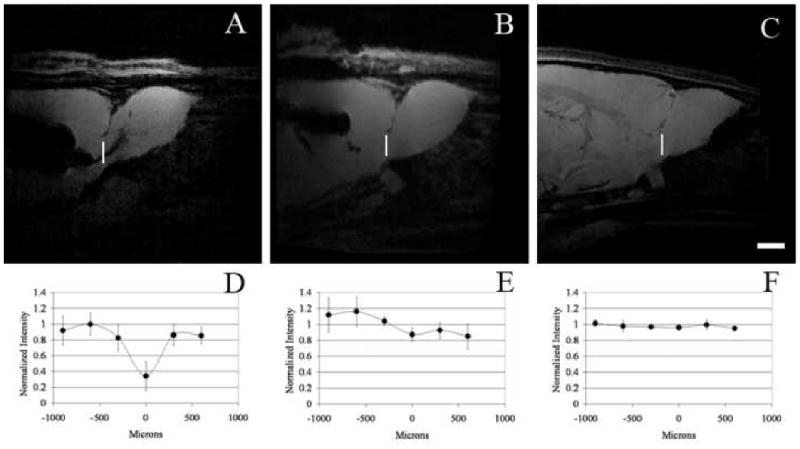

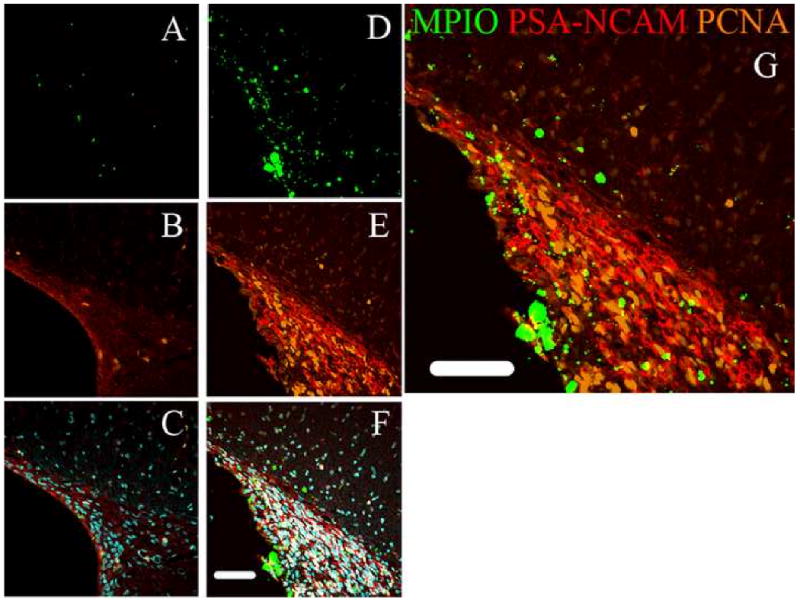

Within two weeks post injection, MPIOs could be detected with MRI in the RMS as shown in panel A of Figure 1. MPIO labeled cells are detectable as dark due to the loss of signal under the imaging parameters used. The RMS is a white matter track that serves to populate the olfactory bulb with new neuroblasts originating from the subventricular zone and can be visualized under T2* weighted conditions with MRI as illustrated in Figure 1, panel B. It was assumed that since the MPIOs were injected into the ventricle, that cells would have to actively transport the particles across the epithelial barrier along the RMS to the olfactory bulb (Shapiro et al., 2006). Nonetheless work by Sawamoto et al (Sawamoto et al., 2006) has shown that migrating neuroblasts follow the CSF flow in the RMS to reach the olfactory bulb which raised a concern that MPIOs were freely diffusing along the RMS and then being taken up locally. To test this, mini-osmotic pumps were used to deliver Ara-C, an anti-mitotic agent that has been shown to inhibit SVZ neurogenesis (Doetsch et al., 1999). This enabled testing if the neuroblasts were essential to observe MPIOs in the RMS and olfactory bulb. Figure 2, panel B shows that MPIOs are not observable in the RMS when Ara-C was infused. In fact the signal in the RMS of the Ara-C infused animal is similar to control animals that have no MPIOs or Ara-C infusion as shown in Figure 2 panel C. This is illustrated graphically in Figure 2, where there is a > 60% decrease of signal in the RMS from the MPIO of control animals and no significant change in signal for the Ara-C infused and control animals. IHC from the MPIO only injected animals and MPIO plus Ara-C infused animals is shown in Figure 3. The RMS is easily identified optically with phase contrast in both sets of animals. However, animals that had Ara-C infused continually for 2 weeks show weak staining of PSA-NCAM, a surface protein necessary for migration, and few cells are positive for the mitotic marker PCNA, both of which are expressed in the SVZ. This is consistent with the work done by Doetsch (Doetsch et al., 1999) where the PSA-NCAM positive network and mitotic cells (identified by BrdU) were eradicated with Ara-C. The animals that only had MPIOs injected show that the PSA-NCAM network and PCNA positive cells are confined to the SVZ, in agreement with previous reports (Abrous et al., 2005; Liu and Rao, 2003; Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994; Luskin, 1993; Suzuki and Goldman, 2003).

Figure 1.

Merge of 15 serial 100 μM isotropic MRI obtained on an 11.7 T instrument using a gradient echo sequence that encompasses the RMS. Two weeks after injection of MPIOs, the large loss of signal in the ventricle is due to the large number of particles injected. Panel A shows a MRI of an animal that has been injected with MPIOs. Arrows indicate contrast due to movement of MPIOs along the RMS into the olfactory bulb. Panel B shows a control animal with no MPIOs. Arrow indicates T1 contrast enabling detection of RMS. (Scale bar = 2 mm)

Figure 2.

Panels A-C are MRI of individual rats injected with MPIOs (A), MPIOs and infused with Ara-C (B), and control animals (C). MRI was obtained at 75 μm isotropic resolution in all cases. Panels D-E represent the corresponding intensity profile through the RMS. The profile is taken at the forebrain olfactory bulb interface and runs dorsally to ventrally, where 0 μm is at the center of the RMS. (D) Profile for rats (n=6) injected with MPIOs. (E) Profile for rats (n=6) injected with MPIOs and infused with Ara-C. (F) Profile for rats (n=3) that were not injected with MPIOs. (Scale bar = 2 mm)

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of the SVZ. Left column (Panels A-C) is from animals injected with Ara-C and MPIOs. Right column (Panels D-F) is from animals injected with MPIOs only. The fluorescence images from the MPIOs are shown in Panels A and D. Panels B and E) represents PSA-NCAM which stains for migrating neural progenitors overlaid with PCNA that stains for mitotic cells; C and F) represents combination of all images overlaid with DAPI counterstaining. Panel G is an enlargement of the MPIO only animals. In all cases there was a large reduction in MPIOs and precursors in the SVZ due to Ara-C. (Scale bars = 100 μm)

Characterization of MPIO Labeled Cell Phenotype

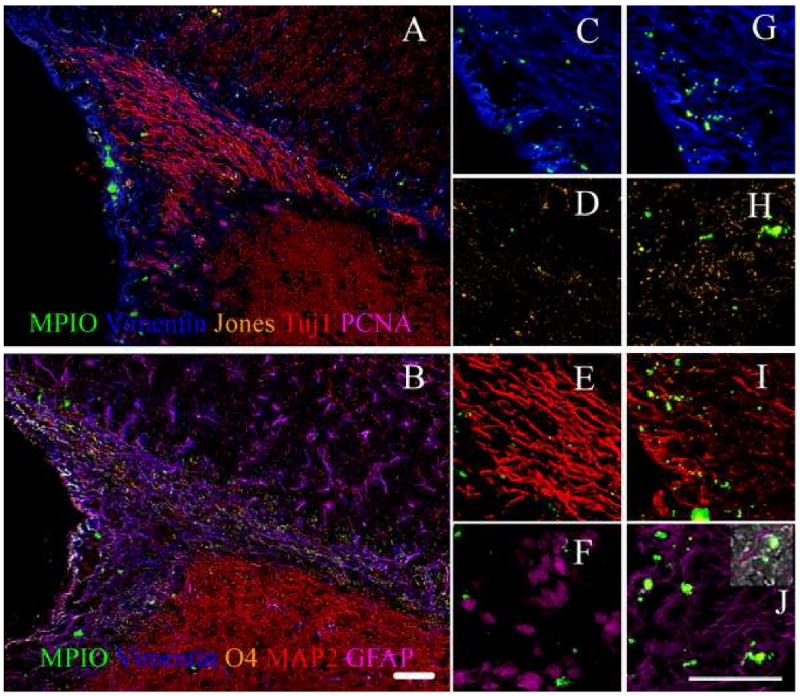

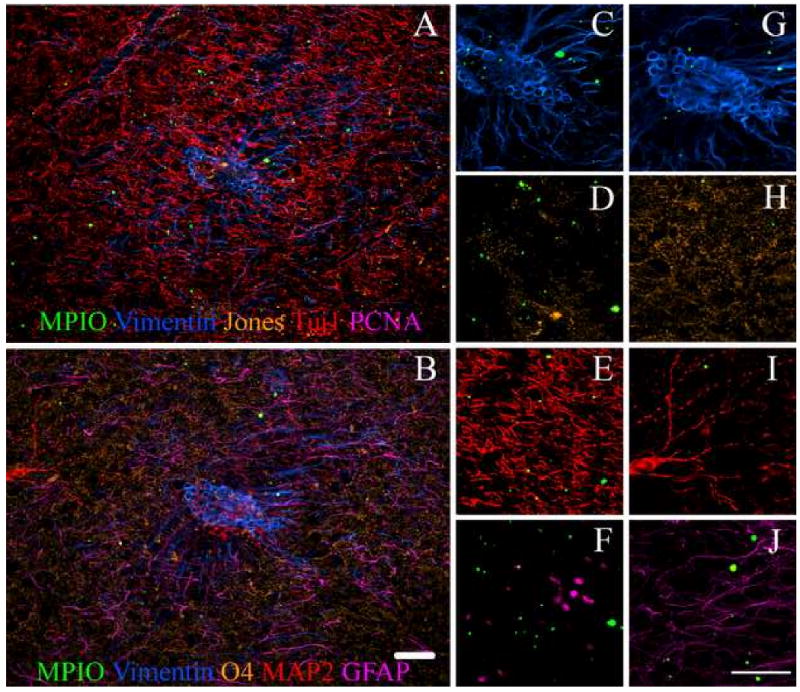

IHC and immunocytochemistry (ICC) were used to identify and quantify the cell types that the MPIOs labeled in the SVZ, RMS, and olfactory bulb. Figures 4 and 5 shows fluorescence images from IHC on sections of the SVZ and olfactory bulb of an animal injected with MPIOs. Cells were identified that contained MPIOs and were positive for mitotic migrating neural progenitors as indicated by the presence of PCNA, Tuj 1, JONES, and vimentin in Figures 4 and 5. Astroglial progenitors, type B cells, were also identified that expressed vimentin and GFAP in Figure 4, panels F and I. Oligo progenitors that were MPIO+ were also found in the SVZ and RMS; these cells expressed O4 and vimentin, also shown in Figure 4, panels F and G. Mitotic cells labeled with MPIOs were also identified in the olfactory bulb, however, there were few mitotic cells identified in the olfactory bulb compared to the SVZ and RMS. In Figure 4, panels A and C, there were cells that were positive for both Tuj1 and vimentin and Tuj 1 alone. In fact, both oligoprogenitors and astroglial progenitors were identified by positive staining for vimentin and O4 in panels F and G, and GFAP and vimentin in panels F and I in Figure 4. In contrast mature cell phenotypes containing MPIOs were found in the olfactory bulb based on the lack of vimentin staining illustrated in Figure 5. These included the major neural phenotypes: astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes. The IHC of the olfactory bulb illustrates that younger cells are centrally located, while the mature cells are positioned along the outside. This is what is expected given that the RMS shuttles neuroblasts toward the olfactory bulb where they then radiate outward to become mature cells.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of the SVZ shows all cell types are labeled with MPIOs. Panel A is on one slice and B is on a serial slice. Panels C through F are enlargements of areas in Panel A. Panels G through J are enlargements of areas in Panel B. Panels C and G) represents vimentin which stains for progenitor cells, D) corresponds to Jones that stains for neuroblasts, E) represents Tuj1+ in developing neurons, F) represents PCNA for mitotic cells, H) corresponds to O4+ oligodendrocytes, I) represents MAP2+ for differentiated neurons, and J) represents GFAP+ astrocytes. The inset in Panel J shows the phase contrast image overlaid with fluorescence. This was used to indentify labeled cells. These results illustrate that MPIOs could be identified in progenitor cells that are located rostrally to the ventricle. (Scale bar = 100 μm)

Figure 5.

Immunostaining of the olfactory bulb shows that MPIOs could be detected in all major cells types. Panel A is on one slice and B is on a serial slice. Panels C through F are enlargements of areas in Panel A. Panels G through J are enlargements of areas in Panel B. Panels C and G) represents vimentin which stains for progenitor cells, D) represents Jones that stains for neuroblasts, E) corresponds to Tuj1+ in developing neurons, F) represents PCNA for mitotic cells, H) represents O4+ oligodendrocytes, I) corresponds to MAP2+ for differentiated neurons, and J) represents GFAP+ astrocytes. These results demonstrate MPIOs could be identified in neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes in the olfactory bulb. (Scale bar = 100 μm)

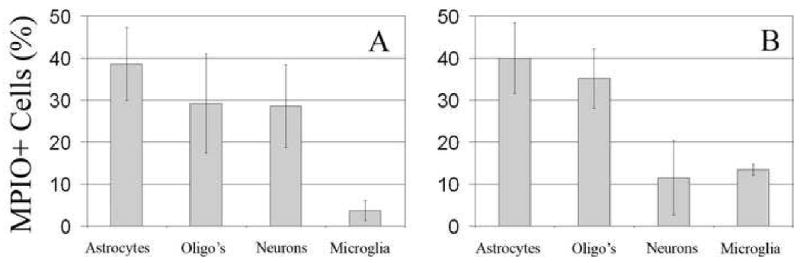

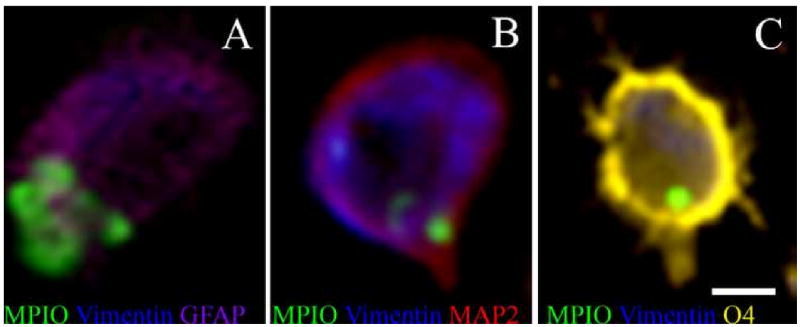

Using FACS and MACS analysis, the MPIO labeled cell phenotypes were quantified. The percent of total cells that were labeled with MPIOs varied from 10% - 35%, however, this was very dependent on the boundaries of dissection of the RMS and the yield of isolating individual cells from the RMS and bulb. However, the MPIO+ cells that were isolated were quantitatively analyzed for cell phenotype. The percent of total MPIO labeled cells that were neurons, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglia are shown in Figure 6 for both the SVZ and olfactory bulb. The distribution of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes as a per cent of total labeled cells was about 35% in the SVZ and olfactory bulb. The distribution of MPIO+ neurons ranged from 11 to 28% with a trend to lower percentages in the olfactory bulb. Finally, 4% -13% of labeled cells were microglia. Most likely microglia get labeled due to apoptosis of progenitors which is known to occur along the RMS and in the bulb (Brunjes and Armstrong, 1996; Winner et al., 2002). Presumably a dying cell labeled with MPIO would lead to MPIO engulfment by microglia. Approximately 3% of the cells sorted in the olfactory bulb were unidentified with the ICC markers used. MPIOs may label endothelial cells around the ventricle; this may account for the unidentified cells because no endothelial marker was used. Cells were also magnetically sorted and the fluorescent images from the ICC are shown in Figure 7. 59% of the astrocytes labeled were also positive for vimentin, suggesting that they are astroglial progenitors whereas 15% were neurons and 37% of oligodendrocytes were progenitors based on vimentin staining. Additionally, astrocytes were consistently identified to contain more MPIOs than either neurons or oligodendrocytes. One to 2 particles were usually identified with neurons or oligodendrocytes, while some of the astrocytes were found to contain as many as 7 particles. Considering that precursors should be labeled equally effectively prior to differentiation, this may indicate that astrocytes also engulf MPIOs when apoptosis occurs along the migratory pathway.

Figure 6.

Lineage distribution of MPIO+ cells isolated from the A SVZ/RMS and B) olfactory bulb analyzed with FACS. Panels A and B illustrate the distribution of MPIOs among the phenotypes. Approximately 3% of the MPIO+ cells in SVZ/RMS were unidentified, perhaps owing to the presence of endothelial cells. At least 100,000 cells were analyzed per trial. (n= 5)

Figure 7.

Immunocytochemistry of cells isolated from a single animal brain that was injected with MPIOs using MACS. Panels A-C show an example of the three neural precursors that derive from neural stem cells: A) astrocytes, B) neurons, and C) oligodendrocytes. 59% of the GFAP(+), 15% of the MAP2(+), and 37% of O4(+) cells were also vimentin(+). (Scale bar = 5 μm)

Discussion

In this study it was demonstrated that migrating neuroblasts are essential for MPIOs to travel rostrally from the lateral ventricle to the olfactory bulb and thus give rise to MRI contrast along the RMS. Using an the anti-mitotic agent, Ara-C, hypointense spots characteristic of iron oxide particles were not identified in the RMS or olfactory bulb with MRI, though they were identified in the ventricles. Without Ara-C, MPIOs were easily identified in the RMS and olfactory bulb. Using IHC, far fewer PCNA+ (marker for mitotic cells) cells were identified in Ara-C infused animals compared to control animals, which is consistent with other reported results (Doetsch et al., 1999). Additionally, the marker for PSA-NCAM was markedly reduced in Ara-C animals. These data provide evidence that even though there is moving cerebral spinal fluid in the RMS, migrating cells are required to observe MPIO movement from the SVZ to the olfactory bulb. Probably the large MPIOs used can not efficiently diffuse through the densely packed space in the RMS. There were a few cells that were labeled with MPIOs in Ara-C infused animals. This may be due to the Ara-C not being 100% efficient at killing mitotic cells consistent with IHC still detecting PCNA+ and PSA-NCAM+ cells in Ara-C treated animals. Alternatively, a small number of MPIOs could potentially enter the CSF and move towards the olfactory bulb.

The labeled cells were characterized using IHC and ICC and quantitated with cytometry. Astroglial progenitors and neuroblasts were identified at the SVZ and RMS. Interestingly, not only were MPIO+ neurons identified in the olfactory bulb but also oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, suggesting that the RMS not only populates the olfactory bulb with neurons but all major neural phenotypes. It has been reported that the astroglial progenitors in the SVZ can self replicate as well as give rise to neurons in the olfactory bulb (Abrous et al., 2005). In cell culture these progenitor cells can differentiate into all the major neural phenotypes but only neurons have been identified in the bulb until recently. Work by Menn et al (Menn et al., 2006) demonstrated that some oligodendrocytes arise from astroglial progenitor cells in the SVZ and can migrate to the olfactory bulb. This is consistent with our results; in addition, astrocytes in the olfactory bulb containing MPIOs were also identified. It could be that the glial progenitors are needed for the new neurons to integrate into the olfactory bulb circuit such as observed during embryonic development (Colon-Ramos and Shen, 2008). Care must be taken when attributing labeled cells to have arisen due to migration of progenitors. It is known that many progenitors undergo apoptosis and other cells would be expected to endocytose the released MPIOs. Indeed the labeling of microglia with many particles and the fact that some astrocytes have many MPIOs indicate that this is potentially occurring throughout the migration pathway. Astrocytes have been shown to have phagocytotic properties in both culture and rodent experiments (Al-Ali et al., 1988; Watabe et al., 1989). Experiments co-labeling progenitors with BrdU and MPIOs or using a recently developed fluorescence technique that labels the cells that first take up MPIOs (Sumner et al., 2007) will enable distinguishing labeled progenitors that have differentiated from cells that have taken up MPIOs from dying cells.

Cytometric analysis revealed that only a small percentage of MPIOs are up taken by microglia, 4% in the SVZ and 14% in the olfactory bulb as shown in Figure 6. The occurrence of labeled microglia is consistent with reports indicating up to 50% of the neural progenitors undergo apoptosis en route and once they reach the olfactory bulb (Brunjes and Armstrong, 1996; Winner et al., 2002). Interestingly, the distribution of MPIO labeled cells is almost uniform amongst the main neural phenotypes, neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes despite the fact that there are more neurons available for labeling. This may be due to the fact that MPIOs are endocytosed by precursors that are already committed to a certain phenotype. In that case, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes may be more endocytotic than neurons and may be the reason for a lower than expected distribution of MPIO+ neurons. The distribution of MPIO+ cells between the SVZ and olfactory bulb remained relatively constant for both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes; however, there is a slight decrease in the percentage of MPIO+ neurons with a corresponding increase in MPIO+ microglia. The difference could be attributed to an increase in apoptosis of the migrating neurons and oligodendrocytes once they reach the olfactory bulb. This would result in an increased number of labeled microglia and perhaps astrocytes.

At the present stage of development there are shortcomings with the present strategy of directly labeling precursors in vivo. Although migrating cells are necessary for MPIO movement, the specific cell phenotype cannot yet be identified in vivo with MRI and histology is still required. Additionally, the large quantity of particles injected into the ventricle results in a large loss of signal and image distortion in the midbrain region. Efficient labeling of the migrating neuroblasts using fewer MPIOs would mitigate this problem. There may be a few ways to accomplish this. First would be to examine the labeling efficiency with dose-dependence study. Secondly would be to inject directly into the SVZ so there is no dilution effect that occurs from injecting into the ventricle, although a potential problem is that the particles are now directly in the CSF that flows to the olfactory bulb and it is difficult to routinely inject into the small RMS region. Alternatively, the labeling efficiency could be increased by modifying the particle surface with antibodies, allowing a particular phenotype to be selectively targeted and then detected with MRI during the migration. Using a targeted approach would reduce the number of particles necessary to label the SVZ cells. Another concern is that some migrating cells die along the RMS as well as in the olfactory bulb (Brunjes and Armstrong, 1996; Winner et al., 2002) so there is a possibility of MPIOs being incorporated into surrounding cells of an apoptotic cell. Microglia are known to efficiently scavenge apoptotic cells in the brain which is why they are often found with many particles. It is possible other cell types could take up particles as well leading to a distribution of labeled cell type in the FACS data.

In conclusion, neural progenitors can be labeled for MRI by direct injection of MPIOs into the ventricle near the SVZ in the RMS. The movement of MPIOs, along the RMS to the olfactory bulb, requires the presence of migrating cells indicating that particle movement to the bulb is not via diffusion in the CSF. Characterization of MPIO labeled cells in the SVZ and olfactory bulb reveal that in addition to neurons, both astrocyte and oligodendrocytes are also labeled. This suggests that the SVZ populates the olfactory bulb with all major phenotypes in the olfactory bulb. Since all the cell types that rat progenitors differentiate into are labeled, it will be possible to observe changes in migration of the cells during learning, plasticity, and brain injury in individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NINDS Intramural Research Program of NIH. We thank N. Bouraoud and S. Dodd, for their technical assistance with animal surgeries and MRI, respectively. We also thank Carolyn Smith for use of the NINDS Light Imaging Facility.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M. Adult neurogenesis: From precursors to network and physiology. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85:523–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ali SY, Al-Zuhair AG, Dawod B. Ultrastructural study of phagocytic activities of young astrocytes in injured neonatal rat brain following intracerebral injection of colloidal carbon. Glia. 1988;1:211–218. doi: 10.1002/glia.440010306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvindrah R, Rougon G, Chazal G. Increased neurogenesis in adult mCD24-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3594–3607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03594.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunjes PC, Armstrong AM. Apoptosis in the rostral migratory stream of the developing rat. Developmental Brain Research. 1996;92:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulte JW, Kraitchman DL. Monitoring cell therapy using iron oxide MR contrast agents. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2004;5:567–584. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulte JWM, Zhang SC, van Gelderen P, Herynek V, Jordan EK, Duncan ID, Frank JA. Neurotransplantation of magnetically labeled oligodendrocyte progenitors: Magnetic resonance tracking of cell migration and myelination. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 1999;96:15256–15261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayre M, Bancila M, Virard I, Borges A, Durbec P. Migrating and myelinating potential of subventricular zone neural progenitor cells in white matter tracts of the adult rodent brain. Molecular And Cellular Neuroscience. 2006;31:748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugani DC, Kedersha NL, Rome LH. Vault immunofluorescence in the brain: new insights regarding the origin of microglia. J Neurosci. 1991;11:256–268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00256.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Ramos DA, Shen K. Cellular conductors: glial cells as guideposts during neural circuit development. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, AlvarezBuylla A. Network of tangential pathways for neuronal migration in adult mammalian brain. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 1996;93:14895–14900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Regeneration of a germinal layer in the adult mammalian brain. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 1999;96:11619–11624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JA, Anderson SA, Kalsih H, Jordan EK, Lewis BK, Yocum GT, Arbab AS. Methods for magnetically labeling stem and other cells for detection by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:621–625. doi: 10.1080/14653240410005267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotts JE, Chesselet MF. Migration and fate of newly born cells after focal cortical ischemia in adult rats. Journal Of Neuroscience Research. 2005;80:160–171. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti A, Bonfanti L, Doetsch F, Caille I, Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA, Galli R, Verdugo JMG, Herrera DG, Vescovi AL. Multipotent neural stem cells reside into the rostral extension and olfactory bulb of adult rodents. Journal Of Neuroscience. 2002;22:437–445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00437.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, Hitchens TK. A non-invasive approach to detecting organ rejection by MRI: Monitoring the accumulation of immune cells at the transplanted organ. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2004;5:551–566. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HY, Tomasiewicz H, Magnuson T, Rutishauser U. The role of polysialic acid in migration of olfactory bulb interneuron precursors in the subventricular zone. Neuron. 1996;16:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levison SW, Goldman JE. Both Oligodendrocytes And Astrocytes Develop From Progenitors In The Subventricular Zone Of Postnatal Rat Forebrain. Neuron. 1993;10:201–212. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90311-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GF, Rao Y. Neuronal migration from the forebrain to the olfactory bulb requires a new attractant persistent in the olfactory bulb. Journal Of Neuroscience. 2003;23:6651–6659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06651.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D, Barker JL. Neural stem cells redefined - A FACS perspective. Molecular Neurobiology. 2004;30:49–76. doi: 10.1385/MN:30:1:049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Otero R, Cavalcante LA. Expression of 9-O-acetylated gangliosides is correlated with tangential cell migration in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1996;204:97–100. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7907–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modo M, Mellodew K, Cash D, Fraser SE, Meade TJ, Price J, Williams SCR. Mapping transplanted stem cell migration after a stroke: a serial, in vivo magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage. 2004;21:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Cholfin JA, Yamada M, Spassky N, Murcia NS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Marin O, Rubenstein JLR, Tessier-Lavigne M, Okano H, Alvarez-Buylla A. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science. 2006;311:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro EM, Gonzalez-Perez O, Manuel Garcia-Verdugo J, Alvarez-Buylla A, Koretsky AP. Magnetic resonance imaging of the migration of neuronal precursors generated in the adult rodent brain. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro EM, Skrtic S, Koretsky AP. Sizing it up: Cellular MRI using micron-sized iron oxide particles. Magnetic Resonance In Medicine. 2005;53:329–338. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro EM, Skrtic S, Sharer K, Hill JM, Dunbar CE, Koretsky AP. MRI detection of single particles for cellular imaging. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences Of The United States Of America. 2004;101:10901–10906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403918101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner JP, Conroy R, Shapiro EM, Moreland J, Koretsky AP. Delivery of fluorescent probes using iron oxide particles as carriers enables in-vivo labeling of migrating neural precursors for magnetic resonance imaging and optical imaging. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2007;12:51504. doi: 10.1117/1.2800294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki SO, Goldman JE. Multiple cell populations in the early postnatal subventricular zone take distinct migratory pathways: A dynamic study of glial and neuronal progenitor migration. Journal Of Neuroscience. 2003;23:4240–4250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04240.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe K, Osborne D, Kim SU. Phagocytic activity of human adult astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in culture. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1989;48:499–506. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winner B, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Aigner R, Winkler J, Kuhn HG. Long-term survival and cell death of newly generated neurons in the adult rat olfactory bulb. European Journal Of Neuroscience. 2002;16:1681–1689. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JM, Kim JH, Song GS, Jung JS. Increase in proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells isolated from postnatal and adult mice brain by Wnt-3a and Wnt-5a. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;288:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerlin M, Levison SW, Goldman JE. Early patterns of migration, morphogenesis, and intermediate filament expression of subventricular zone cells in the postnatal rat forebrain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7238–7249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07238.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]