Summary

In development, pattern formation requires that cell proliferation and differentiation be precisely coordinated. Stomatal development has served as a useful model system for understanding how this is accomplished in plants. While it has been known for some time that stomatal development is regulated by a family of receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and an accompanying receptor-like protein (RLP), only recently have putative ligands been identified. Despite the structural homology demonstrated by the genes that encode these small, secreted peptides, they convey different types of information, vary with one another in their relationship to common signaling components, control distinct aspects of stomatal development, and do so antagonistically. Their discovery has revealed the intricate network of interactions required upstream of RLK signal transduction for the patterning of complex tissues. However, at issue still is whether specific ligand-receptor combinations are responsible for the activation of discrete signaling pathways or spatiotemporal modulation of a common pathway. This review integrates the latest findings regarding RLK-mediated signaling in stomatal development with emerging paradigms in the field.

Introduction

For many multicellular organisms, the coordination of cell proliferation and differentiation during pattern formation is accomplished in part through intercellular communication. Ligand-receptor-based signaling is amenable to short-range, position-dependent forms of communication in which cells preside over the fates of their immediate neighbors. The extent to which signal transduction is activated within target cells can be contingent on signal strength (i.e. amount of ligand produced) and at least two distinct positional relationships: proximity of the signal source and orientation of the source relative to the target(s). While proximity between the signal source and target cells ties into signal strength and is a general requirement for ligand-receptor-based systems, orientation becomes important in situations where the output involves a directional response such as polarized cell growth or orientation of division planes.

In plants, the importance of communication via cell-surface localized receptors is reflected by their considerable representation in the genome and their involvement in a wide array of biological processes. Recent genetic approaches have led to the characterization of RLKs involved in diverse developmental phenomena, including organ abscission (HAESA[1] and EVERSHED [2]), lateral root initiation (ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY4 (ACR4) [3]), root hair and ovule patterning (SCRAMBLED [4]/STRUBBELIG [5]), embryogenesis (RECEPTOR LIKE PROTEIN KINASE1/TOADSTOOL2 [6]), vascular patterning (PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM (PXY) [7,8]) and shoot meristem maintenance (CLAVATA (CLV) [9] and BARELY ANY MERISTEM (BAM) [10] families). Despite these breakthroughs, little is known about how these receptors mediate signal transduction, and genetic relationships with other signaling components remain to be verified biochemically. In many instances the identities of ligands, signaling partners, and substrates remain a mystery.

In stomatal development, both the proximity and orientation of positional cues are important. The frequency and orientation of asymmetric cell divisions and the differentiation of stomata and precursors depend on the identities of neighboring cells (Fig. 1, [11]). It has been known for some time that the ERECTA (ER), ERECTA-LIKE1 (ERL1) and ERECTA-LIKE2 (ERL2) (collectively referred to as the ER-family (ERf)) leucine-rich repeat (LRR) RLKs and the TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) LRR-RLP coordinate these processes in Arabidopsis to ensure that stomata are produced at an appropriate density and that they rarely form in contact [12,13]. However, the relationship between the TMM and ERf receptors is complicated, and while it is conceivable that they dimerize and activate signal transduction in tandem (this has yet to be demonstrated biochemically), they also function antagonistically in a tissue-specific manner [12].

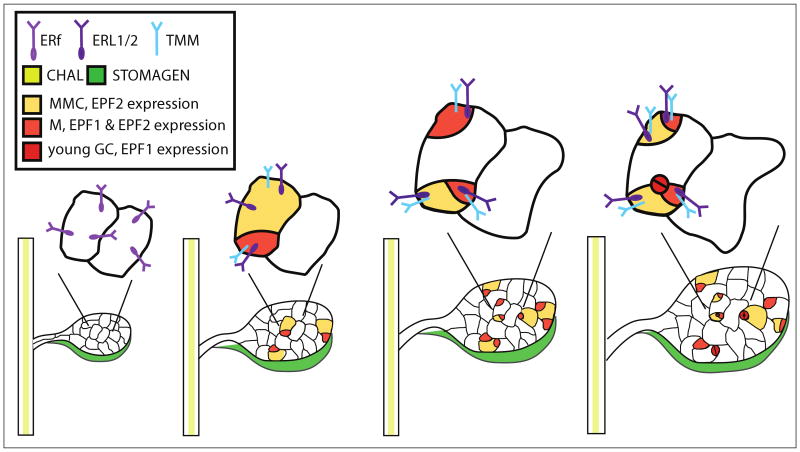

Figure 1. Progression through the stomatal lineage and expression patterns of EPF, ERf and TMM genes.

Depiction of the origin and progression of cells in the stomatal lineage of the leaf epidermis. Examples of divisions creating specific precursor cell types are shown in bulk on the growing leaf. Above each leaf stage are depicted two cells, one stomatal lineage and one not, and their development over time. The expression pattern of ligands (color coded shading as indicated in the key) follows their published transcriptional reporter expression. Receptors (depicted with the extracellular portion as a V-shape) are placed with their intracellular domains in the cell type corresponding to published transcriptional reporter expression. MMC, meristemoid mother cell; M, meristemoid, GC, guard cell.

The recent identification of four members of the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) family of cysteine-rich secreted peptides has helped to define the roles of the TMM and ERf receptors. Genetic analyses demonstrate that EPF1 [14], EPF2 [15,16], CHALLAH (CHAL, also EPFL6) [17], and STOMAGEN (EPFL9) [18-20] affect distinct phases of stomatal development, can function antagonistically, and diverge in their relationship to TMM and the ERf. In addition, the unique expression patterns of the putative ligands in the epidermis (EPF1/2) and underlying tissues (CHAL and STOMAGEN), suggests that they may convey different types of information to cells of the stomatal lineage. Elements of the signaling logic and mechanisms derived from these cases, including how specificity may be conferred on broadly functioning RLKs, are likely to illustrate general principles at work in many other developmental contexts.

Stomatal development requires carefully coordinated cell proliferation and differentiation steps

Examples of most major developmental decisions are found in the stomatal lineage. Entry into the lineage is initiated in the plant epidermis when meristemoid mother cells (MMCs) divide asymmetrically to generate daughter cells of divergent size and fate (Fig. 1 [11]). While the larger daughter cells (referred to as “stomatal lineage ground cells” or “SLGCs”) are capable of further asymmetric divisions, they often expand in size and terminally differentiate. In contrast, the smaller, triangular-shaped daughters (referred to as “meristemoids”) demonstrate the proliferative capacity of stem cells and typically engage in additional asymmetric divisions that amplify the number of cells in the lineage. Stomatal development ceases when meristemoids differentiate into guard mother cells (GMCs) and divide symmetrically to yield stomata: two guard cells flanking a pore. The frequency and orientation of asymmetric divisions that occur next to meristemoids, GMCs, or stomata are regulated in such a manner that stomata rarely form in contact with one another. This so-called “one-cell spacing rule” is violated in tmm and er erl1 erl2 mutant plants [12,21], suggesting that intercellular communication is required for the proper coordination of stomatal development.

Stomatal development is regulated by the ERECTA family of RLKs

The ERf of LRR-RLKs function broadly in aerial plant tissues to promote organ growth [22]. Plants carrying mutations in the founding member (ER) exhibit reduced stature and organ size due to diminished cell proliferation [23]. Like other families of RLKs that regulate plant development (ACR4 [3], PXY [7], and HAESA [1]), the ERf exhibits considerable functional redundancy. In this case, distinct and measurable growth defects of erl1 and erl2 are only revealed in an er background [22]. Promoter-swap experiments suggest that functional differences between ERf members in promoting growth are primarily due to differential expression rather than variation in protein structure [22].

The ERf also maintains a delicate balance between proliferation and differentiation in the developing stomatal lineage. The er erl1 erl2 phenotype involves the formation of massive clusters of guard cells and elevated stomatal densities in all stomata-producing tissues, and its severity (relative to single mutant phenotypes) implies that the ERf may regulate stomatal development in a redundant manner as well [12]. However, in this context ERL1 and ERL2 possess distinct functions not encapsulated by ER. Whereas ER is responsible for restricting entry into the stomatal lineage, ERL1 and ERL2 maintain the proliferative capacity of meristemoids by inhibiting the acquisition of GMC identity [12]. Each ERf member is expressed uniformly in protodermal cells of emerging leaf primordia, but ER expression ceases prior to differentiation while expression of ERL1 and ERL2 is maintained specifically in cells of the stomatal lineage (Fig 1) [12]. These findings indicate that ERL1 and ERL2 are likely responsible for perceiving the positional cues that dictate cell fate decisions within the stomatal lineage. It has not yet been demonstrated whether the contrasting roles of ERf members in stomatal development are due in part to divergent biochemical activities.

The TOO MANY MOUTHS RLP is an entry point for cell-type and tissue specific modulation of ERECTA signaling

Given that RLPs such as TMM lack functional intracellular kinase domains, their participation in signal transduction pathways likely hinges on interactions (physical or otherwise) with proteins that possess such domains. Perhaps the best characterized example of such a partnership in plant development involves the RLK CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and the RLP CLAVATA2 (CLV2), which, along with CLV2's partner kinase CORYNE [24] function cooperatively to restrict stem cell proliferation in the shoot apical meristem of Arabidopsis [25]. However, the relationship between TMM and the ERf differs from that of CLV1 and CLV2 in key ways. Pertinent to this discussion is genetic evidence that TMM is both a potentiator and an inhibitor of ERf signaling [12]. In leaves, tmm phenotypes are consistent with those of ERf mutants: MMCs and SLGCs divide asymmetrically more frequently, meristemoids differentiate into GMCs more readily, and stomata form in clusters, [13,26]. However, in tmm stems and hypocotyls, asymmetric divisions occur rarely and the production of stomata is eliminated [13,27]. Mutations in specific ERf members are epistatic to tmm in stems and in leaves [12], suggesting that the positive and negative roles of TMM in stomatal development may both involve modulation of ER-based signal transduction. The recent characterization of EPF genes involved in TMM- and ER-dependent regulation of stomatal development has provided support for this hypothesis.

Members of the EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) family of small, secreted peptides share common structural motifs

Each of the eleven EPF genes encodes a small protein predicted to undergo secretion and processing into a mature form ∼50 amino acids in length, and to adopt a knot-like conformation by virtue of intramolecular disulfide bridges. [16,19] (Fig. 2). These predictions were confirmed in vivo by isolation of STOMAGEN from the apoplasm as a bioactive 45 aa C-terminal peptide fragment [18,19]. The EPFs are structurally distinct from other known peptide ligands in Arabidopsis, though they share a requirement for conserved cysteines with the defensins [28] and the recently characterized LUREs [29]. EPFs join the ranks of other proteinaceous signal families involved in plant development, such as the DVLs [30], CLEs and IDAs (reviewed in [31]). While it was predicted previously that signaling peptides involved in stomatal development might be processed into active form by the putative protease STOMATAL DENSITY AND DISTRIBUTION [32], genetic analyses suggest that EPFs function independently of this factor.

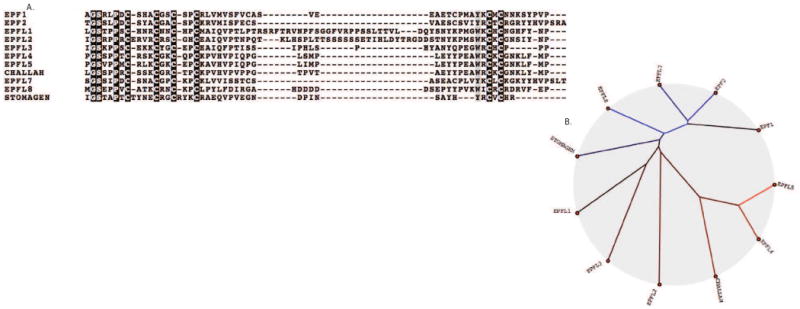

Figure 2. Structural conservation and phylogenetic relationships within the eleven-member EPF gene family.

A. Protein sequence alignment of conserved C-termini generated using ClustalW2. The STOMAGEN propeptide is processed in vivo to yield the bioactive 45-amino-acid C-terminal fragment depicted above [18,19]. Among all EPFs, cysteine residues are strictly conserved at six positions. It was demonstrated with STOMAGEN that these residues form disulfide bridges and are essential for function [19]. B. A Neighbor-Joining phylogeny [36] of EPF family members generated using Kalignvu [37]. In contrast to CHALLAH and EPF1/2, which belong to distinct clades, STOMAGEN fails to cluster with any other EPF genes.

EPF1 and EPF2: Conveying positional information through ERf-signaling

Genetic analyses of EPF1 and EPF2 have uncoupled the roles of ERf-signaling in coordinating cell proliferation and orienting cell division at distinct phases of stomatal development. In epf2 mutants, protodermal cells acquire MMC identity and divide asymmetrically more frequently, resulting in elevated stomatal densities and hyperproliferation of meristemoids, but minimal clustering of stomata [15,16]. In epf1 mutants, asymmetric divisions within the stomatal lineage occur despite the presence of neighboring stomata and precursors, and are often misoriented such that stomata form in contact [14]. EPF1 and EPF2 overexpression phenotypes are dependent on TMM and the ERf, and mutations in either do not discernibly affect stomatal phenotypes in the ERf triple mutant background, suggesting that both EPF1 and EPF2 function upstream of ERf signal transduction [14,16].

Despite their mutual involvement in ERf-signaling, it should be noted that EPF1 and EPF2 seem to differ somewhat in their relationship to TMM. While epf1 and epf2 have no effect on stomatal clustering or density, respectively, in a tmm background, detailed phenotypic analysis revealed that tmm epf2 leaves exhibit the ectopic, arrested meristemoids of epf2 single mutants and reduced stomatal clustering relative to tmm [14-16]. Thus it is likely that EPF2 activates ERf signal transduction both dependently and independently of TMM.

Consistent with their distinct roles in stomatal development, EPF2 is expressed earlier in the lineage than EPF1 (Fig. 1, [15,16]. Promoter-swap experiments revealed that in the epf1 mutant background, expression of pEPF1∷EPF2 but not pEPF2∷EPF1 is sufficient for partial rescue of elevated stomatal clustering [16]. Thus the specialization of EPF1 in regulating stomatal clustering is due in part to differential expression relative to EPF2. However in the epf2 mutant background, expression of pEPF1∷EPF2 but not pEPF2∷EPF1 is sufficient for partial rescue of elevated stomatal density [16]. This suggests that differences in biochemical activity between EPF1 and EPF2 are integral to the role of EPF2 in regulating stomatal density. One intriguing possibility is that the divergent functions of EPF1 and EPF2 involve varying affinities for different combinations of ERf RLKs and/or TMM. Given that ER expression ceases around the time when asymmetric entry divisions take place and that er and epf2 mutants both demonstrate excessive entry divisions, EPF2 functionality may hinge upon interaction with ER.

The above results regarding EPF1 and EPF2 support the idea that these factors both convey positional information about neighboring cell identities among members of the stomatal lineage. However this information appears to be interpreted in distinct ways by various receptor-combinations in the target cells. Whereas the level of EPF2 determines whether target cells will divide asymmetrically, the orientation of the EPF1 signal source may dictate the directionality of asymmetric divisions. The idea that RLKs enable cells to perceive and respond to signal intensity and orientation is gaining traction due to recent characterization of the PXY-CLE41 receptor-ligand pair in Arabidopsis [7,8]. Vascular development is an elegant system for the investigation of how cell divisions are oriented because entire files of meristematic initials must divide precisely along the apical-basal axis in a coordinated manner to produce well-ordered xylem. Proper orientation of these divisions is dependent on the PXY family of LRR-RLKs expressed in the procambium and the CLV3/ESR-related (CLE) ligands CLE41 and CLE44, expressed in the adjoining phloem [7,8]. Ectopic expression of CLE41 in opposing cells of the procambium and xylem (but not overexpression in the phloem) misorients the divisions of the meristematic initials [33], suggesting that polarized activation of RLK signal transduction is required for proper cell division orientation in the incipient vasculature. Stomatal development involves a more modular pattern of cells that generate and perceive intercellular signals, but it is conceivable that similar mechanisms are responsible for orienting cell divisions in each case.

STOMAGEN: Antagonist of ERf-mediated signaling

STOMAGEN is the first positively-acting signaling peptide to be identified in stomatal development. Overexpression and knockdown experiments demonstrate that STOMAGEN expression positively correlates with stomatal density in all stomata-producing tissues [15,18,19]. STOMAGEN is expressed broadly in the mesophyll and not in stomata or precursors [18,19], suggesting that it does not convey positional information from within the stomatal lineage in the same manner as EPF1 and EPF2. However, like EPF1 and EPF2, STOMAGEN requires TMM for function, as STOMAGEN knockdown or overexpression has no effect on stomatal density in the leaves or stems of tmm mutants [18,19].

Given that STOMAGEN and EPF1/2 function antagonistically and require a common signaling component in TMM, one plausible hypothesis is that STOMAGEN inhibits the function of EPF1 and EPF2 by competitive inhibition. This system could have evolved simply via the degeneration of an EPF family member such that it is capable of binding TMM/ER complexes without activating signal transduction. In this manner, the requirement for TMM in EPF1/2-mediated ERf signaling could be exploited as a means for signal attenuation. However, if this hypothesis is correct, there must be other ligands involved because knockdown and overexpression experiments in epf1 and epf2 mutant backgrounds have clearly demonstrated that STOMAGEN regulates stomatal development in the absence of these factors [18,20]. While it has also been reported that application of 10μM STOMAGEN peptide has no effect on stomatal density in epf1 epf2 double mutants [19] this apparent discrepancy could be due to technical challenges associated with synthetic STOMAGEN application.

Assuming that STOMAGEN functions independently of EPF1 and EPF2, another possibility is that STOMAGEN and TMM are involved in the activation of a discrete signaling pathway that promotes stomatal development. The idea of structurally-related peptides functioning antagonistically in such a manner is not as far-fetched as it might seem. It has been demonstrated in Zinnia cell culture that the application of various CLE peptides can have opposing effects on vascular differentiation, likely via distinct pathways [8,34].

CHALLAH: Bringing out TMM's alter ego

While the battle between positive and negative EPFs rages on throughout the plant epidermis, discovery of chal as a suppressor of tmm in stems illustrates how ligand-receptor dynamics can redefine the relationship between signaling components in a tissue-specific manner. In chal tmm stems and hypocotyls, the production of stomata is restored and stomatal lineage cells are produced at a greater frequency relative to the tmm single mutant, suggesting that CHAL negatively regulates entry and progression through the stomatal lineage [17]. While broad CHAL overexpression can decrease stomatal densities throughout the plant, transcriptional reporter analysis confirmed that its expression is restricted to internal layers of the stem and hypocotyls [17]. Consistent with CHAL functioning in opposition to TMM in an ERf-dependent pathway, CHAL overexpression phenotypes are exacerbated in the tmm mutant background and mitigated by ERf mutations [17]. Given that erl1 and erl2 chal enhance stomatal production in the tmm hypocotyls to a greater extent than chal alone, it is possible that CHAL functions redundantly with other EPFs to activate signaling via these ERf members [17]. Interestingly, tmm;chal;er triple mutants fail to produce stomata in hypocotyls, suggesting that ER may serve as a buffer to limit the activation of ERL1 and ERL2 [17].

Thus, while TMM functions cooperatively with EPF1, EPF2 and the ERf to negatively regulate aspects of stomatal development in a broad sense; this role is overshadowed by the repressive effect of TMM on CHAL-ERf signaling in stems and hypocotyls. Among many possibilities, the mechanistic basis for TMM-CHAL antagonism could involve titration of CHAL ligand by TMM and/or the formation of unproductive CHAL-TMM-ERf complexes. A common strategy was recently highlighted by the demonstration that mutations in the CLV1-related BAM RLKs enhance clv1 meristem defects but also suppress phenotypes associated with CLV1's ligand clv3 [10]. This led the authors to conclude that BAM1 and BAM2 may inhibit CLV1 signaling at the meristem flanks via sequestration of CLV3 while functioning redundantly with CLV1 in the meristem center [10]. In interpreting the role of CHAL, one must be careful not to assume that its primary role is to regulate stomatal development. It is entirely possible that CHAL activates ERf signaling in the inner tissues and that its role in stomatal development is only manifested in the absence of buffering from TMM.

Conclusions

In contrast to the bulk of knowledge concerning the role of hormones in plant development, our understanding of peptide-based signaling is still in its infancy. This is likely due in part to genetic redundancies and technical challenges associated with analyzing low abundance extracellular and membrane proteins. In addition to furthering our understanding of the patterning mechanisms involved in stomatal development (Fig. 3), genetic characterization of the EPF family members has elucidated several key themes of ligand-receptor dynamics that resonate with other examples in plant biology: EPF1 and EFP2 have shored up the prospect that TMM and the ERf function cooperatively to control the orientation and frequency of asymmetric divisions, but they have also highlighted the importance of signal source in effecting directional outputs. STOMAGEN has revealed that stomatal development is receptive to positive signals via TMM but it has also cemented the idea that homologous signaling peptides can function antagonistically. CHAL has explained the antagonistic effects of the tmm mutation in different tissues, but it has also demonstrated how receptors are capable of buffering their partners. Collectively, the four EPF family members verify that pattern formation involves both tissue and cell-type specific modes of intercellular communication.

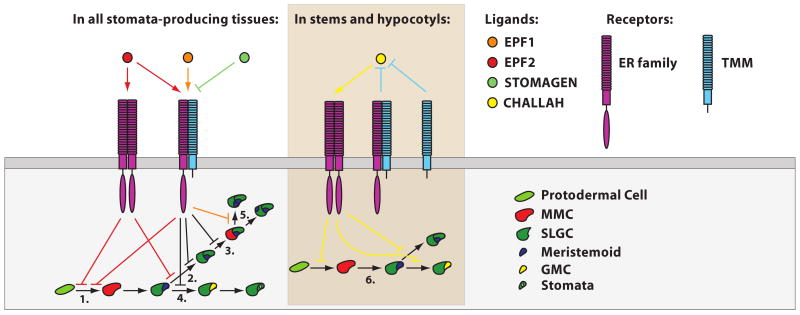

Figure 3. Genetic model for EPF signaling in stomatal development.

The EPF family peptides regulate distinct phases of stomatal development and diverge in their relationship to TMM and the ERf. EPF2 (red) restricts acquisition of MMC identity in protodermal cells (1.) and activates ERf-signaling in the presence and absence of TMM. EPF2 may also function synergistically with EPF1 (orange) (and TMM-dependently) to inhibit amplifying asymmetric divisions (2.), the acquisition of MMC identity among SLGCs (3.), and the meristemoid to GMC transition (4.). EPF1 functions TMM-dependently to orient the production of satellite meristemoids such that they do not form in contact with stomata or precursors (5). STOMAGEN (green) may inhibit TMM-mediated signaling by binding TMM receptor complexes in competition with other EPFs. In a subset of stomata-producing tissues (such as stems and hypocotyls), TMM titrates CHAL (yellow) to prevent CHAL from activating ERf signaling complexes. Ectopic activation of ER-signaling by CHALLAH inhibits entry and progression through the stomatal lineage (6.). All depicted relationships are based on genetic data. In the above figure, arrows or T-bars indicate activation and inhibition, respectively and are colored to correspond with the factors responsible. Black T-bars correspond with roles that may be fulfilled collectively by EPF1 and EPF2. For the sake of simplicity, ERf members are depicted en masse, but it is important to recognize that ER, ERL1, and ERL2 function in distinct phases of stomatal development.

Given that the above data is almost entirely genetic, cell-biological and biochemical approaches will be necessary to demonstrate the formation of receptor complexes and investigate the relative affinities of the respective components. However, to forward understanding of RLK-signaling in plant development, ultimately one must look downstream of interactions between TMM, the ERf and the EPFs and determine whether they confer distinct substrate specificities by identifying direct targets of ERf kinase activity. Phosphoproteomic approaches, similar to those used to dissect brassinosteroid signaling may serve well in this regard [35]. Ultimately the elucidation of EPF-ERf signaling pathways may provide a mechanistic basis for understanding how common signaling components are employed towards the fulfillment of distinct developmental objectives.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Gray, Ikuko Hara-Nishimura, Keiko Torii and members of our lab for discussions about signaling complexity and apologize to those whose work we could not include due to spatial constraints. Work on stomatal development in our lab is funded by National Institutes of Health 1R01GM086632-01 and National Science Foundation IOS-0845521.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Matthew H. Rowe, Email: mattrowe@stanford.edu.

Dominique C. Bergmann, Email: dbergmann@stanford.edu.

Reference List

- 1.Cho SK, Larue CT, Chevalier D, Wang H, Jinn TL, Zhang S, Walker JC. Regulation of floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;40:15629–15634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805539105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leslie ME, Lewis MW, Youn JY, Daniels MJ, Liljegren SJ. The EVERSHED receptorlike kinase modulates floral organ shedding in Arabidopsis. Development. 2010;3:467–476. doi: 10.1242/dev.041335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Smet I, Vassileva V, De Rybel B, Levesque MP, Grunewald W, Van Damme D, Van Noorden G, Naudts M, Van Isterdael G, De Clercq R, et al. Receptor-Like Kinase ACR4 Restricts Formative Cell Divisions in the Arabidopsis Root. Science. 2008;5901:594–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1160158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwak SH, Shen R, Schiefelbein J. Positional signaling mediated by a receptor-like kinase in Arabidopsis. Science. 2005;5712:1111–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1105373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevalier D, Batoux M, Fulton L, Pfister K, Yadav RK, Schellenberg M, Schneitz K. STRUBBELIG defines a receptor kinase-mediated signaling pathway regulating organ development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;25:9074–9079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503526102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nodine MD, Yadegari R, Tax FE. RPK1 and TOAD2 are two receptor-like kinases redundantly required for arabidopsis embryonic pattern formation. Dev Cell. 2007;6:943–956. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher K, Turner S. PXY, a receptor-like kinase essential for maintaining polarity during plant vascular-tissue development. Curr Biol. 2007;12:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Hirakawa Y, Shinohara H, Kondo Y, Inoue A, Nakanomyo I, Ogawa M, Sawa S, Ohashi-Ito K, Matsubayashi Y, Fukuda H. Non-cell-autonomous control of vascular stem cell fate by a CLE peptide/receptor system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;39:15208–15213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808444105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In a directed screen for mutants insensitive to the effects of the CLE peptide TDIF on vascular differentation, the authors identify the TDIF receptor TDR (PXY). Using photoaffinity labeling in BY-2 cells, the authors demonstrate that TDR specifically binds TDIF and not related CLE peptides.

- 9.Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1997;4:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeYoung BJ, Clark SE. BAM Receptors Regulate Stem Cell Specification and Organ Development Through Complex Interactions With CLAVATA Signaling. Genetics. 2008;2:895–904. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergmann DC, Sack FD. Stomatal Development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.104023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shpak ED, McAbee JM, Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Stomatal patterning and differentiation by synergistic interactions of receptor kinases. Science. 2005;5732:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1109710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang M, Sack FD. The too many mouths and four lips mutations affect stomatal production in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1995;12:2227–2239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara K, Kajita R, Torii KU, Bergmann DC, Kakimoto T. The secretory peptide gene EPF1 enforces the stomatal one-cell-spacing rule. Genes Dev. 2007;14:1720–1725. doi: 10.1101/gad.1550707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **15.Hunt L, Gray JE. The signaling peptide EPF2 controls asymmetric cell divisions during stomatal development. Curr Biol. 2009;10:864–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper (along with [**16]) identifies EPF2 as a negative regulator of stomatal development. Genetic analyses demonstrate that EPF2 functions earlier in stomatal development than EPF1 and governs the frequency rather than the orientation of asymmetric divisions via ERf signaling.

- **16.Hara K, Yokoo T, Kajita R, Onishi T, Yahata S, Peterson KM, Torii KU, Kakimoto T. Epidermal cell density is autoregulated via a secretory peptide, EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR 2 in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;6:1019–1031. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper (along with [**15]) identifies EPF2 as a negative regulator of stomatal development. Analysis of reporter-gene expression suggests that EPF2 restricts the acquisition of MMC identity among protodermal cells, while promoter-swap experiments reveal the basis for functional divergence between EPF1 and EPF2.

- **17.Abrash EB, Bergmann DC. Regional specification of stomatal production by the putative ligand CHALLAH. Development. 2010 doi: 10.1242/dev.040931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identify CHAL (EPFL6) in a screen for mutations that suppress tmm in stems and hypocotyls. Genetic experiments suggest that TMM is responsible for inhibiting the activation of ERf signaling by CHAL.

- **18.Sugano SS, Shimada T, Imai Y, Okawa K, Tamai A, Mori M, Hara-Nishimura I. Stomagen positively regulates stomatal density in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper (along with [*19, *20]) identifies the EPF family member STOMAGEN (EPFL9) as a positive regulator of stomatal development. The authors demonstrate that STOMAGEN is expressed in the mesophyll and is processed in vivo to yield a bioactive 45 amino acid C-terminal fragment. Genetic experiments suggest that STOMAGEN functions independently of EPF1 and EPF2, but shares a requirement for the TMM receptor.

- *19.Kondo T, Kajita R, Miyazaki A, Hokoyama M, Nakamura-Miura T, Mizuno S, Masuda Y, Irie K, Tanaka Y, Takada S, et al. Stomatal density is controlled by a mesophyll-derived signaling molecule. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper (along with [**18, *20]) identifies EPFL9 (STOMAGEN) as a positive regulator of stomatal development. Structural analysis reveals that disulfide bonds are integral to EPL9 structure and function.

- *20.Hunt L, Bailey KJ, Gray JE. The signalling peptide EPFL9 is a positive regulator of stomatal development. New Phytol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See annotation to Refs. [**18, *19].

- 21.Nadeau JA, Sack FD. Control of stomatal distribution on the Arabidopsis leaf surface. Science. 2002;5573:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1069596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shpak ED, Berthiaume CT, Hill EJ, Torii KU. Synergistic interaction of three ERECTA-family receptor-like kinases controls Arabidopsis organ growth and flower development by promoting cell proliferation. Development. 2004;7:1491–1501. doi: 10.1242/dev.01028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shpak ED, Lakeman MB, Torii KU. Dominant-negative receptor uncovers redundancy in the Arabidopsis ERECTA Leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase signaling pathway that regulates organ shape. Plant Cell. 2003;5:1095–1110. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller R, Bleckmann A, Simon R. The receptor kinase CORYNE of Arabidopsis transmits the stem cell-limiting signal CLAVATA3 independently of CLAVATA1. Plant Cell. 2008;4:934–946. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong S, Trotochaud AE, Clark SE. The Arabidopsis CLAVATA2 gene encodes a receptor-like protein required for the stability of the CLAVATA1 receptor-like kinase. Plant Cell. 1999;10:1925–1934. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geisler M, Nadeau J, Sack FD. Oriented asymmetric divisions that generate the stomatal spacing pattern in arabidopsis are disrupted by the too many mouths mutation. Plant Cell. 2000;11:2075–2086. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhave NS, Veley KM, Nadeau JA, Lucas JR, Bhave SL, Sack FD. TOO MANY MOUTHS promotes cell fate progression in stomatal development of Arabidopsis stems. Planta. 2009;2:357–367. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0835-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverstein KA, Moskal WA, Jr, Wu HC, Underwood BA, Graham MA, Town CD, VandenBosch KA. Small cysteine-rich peptides resembling antimicrobial peptides have been under-predicted in plants. Plant J. 2007;2:262–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuda S, Tsutsui H, Shiina K, Sprunck S, Takeuchi H, Yui R, Kasahara RD, Hamamura Y, Mizukami A, Susaki D, et al. Defensin-like polypeptide LUREs are pollen tube attractants secreted from synergid cells. Nature. 2009;7236:357–361. doi: 10.1038/nature07882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen J, Lease KA, Walker JC. DVL, a novel class of small polypeptides: overexpression alters Arabidopsis development. Plant J. 2004;5:668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2003.01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butenko MA, Vie AK, Brembu T, Aalen RB, Bones AM. Plant peptides in signalling: looking for new partners. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;5:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger D, Altmann T. A subtilisin-like serine protease involved in the regulation of stomatal density and distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2000;9:1119–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Etchells JP, Turner SR. The PXY-CLE41 receptor ligand pair defines a multifunctional pathway that controls the rate and orientation of vascular cell division. Development. 2010;5:767–774. doi: 10.1242/dev.044941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; By ectopically expressing the PXY ligand CLE41 in opposing vascular tissues, the authors demonstrate convincingly that asymmetric cell divisions in the procambium are oriented by the polarized activation of RLK signal transduction.

- 34.Ito Y, Nakanomyo I, Motose H, Iwamoto K, Sawa S, Dohmae N, Fukuda H. Dodeca-CLE peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science. 2006;5788:842–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1128436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35.Tang W, Kim TW, Oses-Prieto JA, Sun Y, Deng Z, Zhu S, Wang R, Burlingame AL, Wang ZY. BSKs mediate signal transduction from the receptor kinase BRI1 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;5888:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1156973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using a phosphoproteomic approach involving prefractionation and 2D DIGE, the authors identify BSKs1-3 as direct targets of the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1.

- 36.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassmann T, Sonnhammer EL. Kalign, Kalignvu and Mumsa: web servers for multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;(Web Server issue):W596–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]