Abstract

Background

The neighborhood distribution of education (education inequality) may influence substance use among neighborhood residents.

Methods

Using data from the New York Social Environment Study (conducted in 2005; n=4,000), we examined the associations of neighborhood education inequality (measured using Gini coefficients of education) with alcohol use prevalence and levels of alcohol consumption among alcohol users. Analyses were adjusted for neighborhood education level, income level, and income inequality, as well as for individual demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and history of drinking prior to residence in the current neighborhood. Neighborhood social norms about drinking were examined as a possible mediator.

Results

In adjusted generalized estimating equation regression models, one-standard-deviationhigher education inequality was associated with 1.18 times higher odds of alcohol use (logistic regression odds ratio = 1.18, 95% confidence interval 1.08–1.30) but 0.79 times lower average daily alcohol consumption among alcohol users (Poisson regression relative rate = 0.79, 95% confidence interval 0.68–0.92). The results tended to differ in magnitude depending on respondents’ individual educational levels. There was no evidence that these associations were mediated by social drinking norms, although norms did vary with education inequality.

Conclusions

Our results provide further evidence of a relation between education inequality and drinking behavior while illustrating the importance of considering different drinking outcomes and heterogeneity between neighborhood subgroups. Future research could fruitfully consider other potential mechanisms, such as alcohol availability or the role of stress; research that considers multiple mechanisms and their combined effects may be most informative.

Keywords: education, inequality, neighborhood, alcohol, norms

1. Introduction

Alcohol use is the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States (Naimi et al., 2003). Excessive alcohol use is associated with a host of public health problems including cancers, hepatitis, fetal alcohol syndrome, unintentional injuries, and violence (Lindberg and Amsterdam, 2008; Naimi et al., 2003; Standridge et al., 2004). Patterns of alcohol consumption vary widely with individual education levels: higher educational attainment is associated with more overall drinking but less binge or heavy drinking (Karlamangla et al., 2006; Kerr et al., 2009; Naimi et al., 2003; Standridge et al., 2004; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). Alcohol use also varies with neighborhood education levels: the overall prevalence of alcohol use tends to be higher in neighborhoods with high proportions of more highly educated residents (Chuang et al., 2007; Heslop et al., 2009), while heavy drinking is more prevalent in neighborhoods characterized by lower education levels (Bernstein et al., 2007; Hill and Angel, 2005; Mulia et al., 2008).

The neighborhood distribution of education (education inequality) may also influence health and health behaviors such as alcohol use, independent of the neighborhood level of education. The relation between the distribution of income (income inequality) and health has been widely examined over the last fifteen years (Beckfield, 2004; Daly et al., 1998; Kahn et al., 1999; Kawachi and Kennedy, 1999; Lynch et al., 2004; Subramanian and Kawachi, 2004; Wilkinson, 1994; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2006) and a number of potential mechanisms through which area income inequality could negatively affect health have been proposed (Kawachi and Kennedy, 1999). These mechanisms are pertinent to education inequality in a general sense. However, just as individual income and education may influence health in interconnected but different ways (Adler and Newman, 2002; Ross and Wu, 1995; Singh-Manoux et al., 2002), so may income inequality and education inequality. For example, the psychosocial ill effects of relative deprivation hypothesized to accompany income inequality (Kawachi and Kennedy, 1999; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2006) may not accompany education inequality if class identity is defined more by income than by education.

The results of two previously published studies support an association between neighborhood education inequality and health that differs from the association between income inequality and health. In an ecological analysis of neighborhoods, Galea and Ahern (2005) found that high education inequality (i.e., a wide range of educational attainment levels among residents) was associated with positive outcomes on health indicators that are susceptible to short-term changes in the neighborhood social environment: homicide, lack of prenatal care, low birth weight, and infant mortality. This result contrasts with studies associating higher income inequality with worse population health (Subramanian and Kawachi, 2004). In a multilevel analysis, Galea et al. (2007a) found that higher neighborhood education inequality was associated with a higher prevalence of alcohol use, but among drinkers was associated with consuming fewer drinks. In a separate study of the same population, higher income inequality was also associated with a higher prevalence of alcohol use but was associated with higher alcohol consumption among drinkers (Galea et al., 2007b).

One way neighborhood education inequality may influence alcohol use is by affecting social norms about drinking. Neighborhoods with high education inequality may have weaker social norms because high education inequality is indicative of a heterogeneous population whose members may be less likely to share the same values and individual norms (Caetano and Clark, 1999; Winkleby et al., 1992). Neighborhood social norms about drinking have been demonstrated to influence residents’ alcohol use (Ahern et al., 2008; Greenfield and Room, 1997; Moore et al., 2005).

The most common pattern of alcohol use in the United States is moderate consumption; that is, neither abstention nor heavy consumption (Moore et al., 2005; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). If education inequality influences alcohol use among residents through weakened neighborhood social norms, we might expect greater departures from this normative pattern in neighborhoods with high education inequality. While these departures could occur in either direction, the findings of Galea et al. (2007a) suggest an association of high education inequality with higher alcohol-use prevalence but lower consumption among drinkers. If neighborhood norms mediate a relation between education inequality and drinking behavior, regardless of direction, we would expect a modeled statistical association between them to be attenuated with the addition of norms into the model (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Petersen et al., 2006).

Drinking behavior may be influenced not only by neighborhood norms, but also by norms specific to neighborhood subgroups. For example, studies of college drinking have found drinking behavior to be more closely related to descriptive drinking norms when the referent group is more specific to the respondent (Larimer et al., 2009; Perkins, 2002) and differences in drinking behavior among racial/ethnic subgroups mirror differences in alcohol norms (Caetano and Clark, 1999). In neighborhoods with high education inequality, population subgroups with different norms may come into contact and influence one another. Thus, education inequality may influence drinking behavior not only by affecting overall neighborhood drinking norms but by increasing subgroups’ contact and affecting group-specific norms.

The variation in drinking patterns between groups with different levels of education (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008) suggests that individual educational attainment levels may delineate neighborhood subgroups whose norms differ; any influence of education inequality on drinking behavior through changed norms might therefore also differ between education groups. If this is the case, the modeled association between education inequality and drinking behavior may vary between strata defined by educational attainment levels. Furthermore, if education inequality affects drinking through subgroup-specific norms, the overall association would be more sensitive to adjustment for subgroup-specific norms than to overall neighborhood norms. Analyses by education strata would reveal the subgroups in which the education inequality and drinking relation was explained by norms.

In this study, we empirically assessed the relation between neighborhood education inequality and alcohol use in New York City. We explicitly examined the role of overall and education-subgroup-specific neighborhood drinking norms as possible mediators between education inequality and alcohol use.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

The data used for this study were from the New York Social Environment Study (NYSES), a population-based study of 4,000 New York City residents who were interviewed by phone between June and December 2005. Households were contacted using random-digit dialing. One adult aged 18 or over, selected by choosing the adult who most recently celebrated or would next celebrate a birthday, was interviewed in each household. The survey consisted of a structured questionnaire conducted in either Spanish or English. To account for respondents’ probability of selection for the interview, responses were weighted by the ratio of the number of people to the number of phone lines in the respondent’s household.

2.2 Measures

Drinking behavior was measured using the World Mental Health Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview alcohol module (Kessler et al., 2004; Kessler and Ustun, 2004). Respondents were asked at what age they had their first drink, at what age they started drinking at least 12 drinks per year, and the frequency of their drinking over the previous 12 months. For this analysis, overall alcohol use was measured by a binary variable reflecting whether a respondent reported drinking at least 12 drinks in the previous 12 months. The level of alcohol consumption for each drinker was calculated by multiplying the average number of days the respondent reported drinking per month by the average number of drinks he/she reported drinking on each drinking day and then dividing by 30 to give the average number of drinks per day.

To define neighborhoods, respondents’ addresses were geo-coded to New York City’s 59 community districts. The community districts were initially defined as proxies for neighborhoods in 1975 after a process organized by the Department of City Planning involving consultations with residents (New York City Department of City Planning, 2008). The districts are well defined and each has an administrative community board. Because of differences in population density, some community districts may contain several resident-defined neighborhoods. Nonetheless, previous studies have found evidence that the community districts represent neighborhoods whose characteristics may affect the health and behavior of their residents (Ahern et al., 2008; Bernstein et al., 2007; Galea and Ahern, 2005; Galea et al., 2007a).

The education Gini coefficient was calculated as a measure of education inequality at the neighborhood level using data from the 2000 U.S. Census. The education Gini coefficient is a relative measure of inequality ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 represents perfect inequality; an analogous measure has been used extensively in the income inequality literature (Thomas et al., 2000). It is given by

where E is the education Gini coefficient, μ is the population average educational attainment, n is the number of education levels, yi and yj represent the years of education at two different education levels, and pi and pj represent the proportions of the population who have attained those two levels (Galea and Ahern, 2005; Thomas et al., 2000). The years of education associated with each education level is either the midpoint or the most likely value of each category (Galea and Ahern, 2005).

Restrictive drinking norms were measured using questions modified from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2007). Respondents were asked if they felt it was unacceptable for adults to drink alcoholic beverages; response options were “acceptable,” “unacceptable,” and “don’t care.” The neighborhood norms measure was the proportion of respondents in the neighborhood who felt it was unacceptable for adults to drink alcoholic beverages. Education-subgroup-specific norms measures were calculated by aggregating the responses separately for each level of individual educational attainment within each neighborhood. The subgroup-specific measure was restricted to within-neighborhood education subgroups containing at least two respondents.

Individual-level confounders included in the analysis were educational attainment, sex, race, marital status, gender, household income, student status, and alcohol use prior to moving to the current neighborhood of residence. Neighborhood-level mean educational attainment, median income, and income inequality (measured using income Gini coefficients) were calculated from 2000 U.S. census data.

2.3 Analysis

Because of the strong negative correlation between neighborhood-level average educational attainment and education inequality (r = -0.84, p < 0.001), we used linear regression to adjust education Gini values for mean educational attainment (in years) before conducting the analysis. Therefore, the primary explanatory variable in the analysis models is interpretable as education Gini values for a fixed level of neighborhood-level mean educational attainment. While the results were similar when education Gini and mean educational attainment were included as separate explanatory variables, this method allowed for a more precise adjustment for mean educational attainment and facilitated interpretation of the results.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression models were used to examine the association between neighborhood education inequality and alcohol use while controlling for confounders and accounting for possible correlations between respondents in the same neighborhoods (Hanley et al., 2003; Zeger and Liang, 1986). Overall alcohol use and the average number of drinks per day among drinkers were respectively analyzed using logistic and Poisson regression. As an initial test of the hypothesis that social norms mediate an association between education inequality and drinking behavior, models were run both without and with the norms variables (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Petersen et al., 2006). There was no interaction between education inequality and norms in our data, thus this approach can be used to estimate the direct effect of education inequality(Petersen et al., 2006) Attenuation of an association between education inequality and drinking behavior following adjustment for overall neighborhood drinking norms would suggest that drinking behavior may differ in neighborhoods with different levels of education inequality because of varying neighborhood drinking norms. Similarly, attenuation of the association following adjustment for education-subgroup-specific norms would suggest the influence of subgroup-specific drinking norms that, at least for some subgroups, vary with education inequality. Separate mediation analyses were conducted for each of the individual educational attainment strata. This permitted us to explicitly examine differences between subgroups in the association between education inequality and drinking behavior, as well as the mediation of these associations by overall and subgroup-specific neighborhood norms.

3. Results

The respondent population was demographically similar to the overall population of New York City . Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population and neighborhoods are presented in table 1. Out of a total of 4,000 respondents, the study population for the analysis of overall alcohol use comprised 3,888 respondents who did not have missing information; the analyses of alcohol consumption quantity included 1,541 respondents who reported being drinkers. The cooperation rate for the survey ((participated + screened out)/(participated + screened out + refused)) was 54%; the response rate ((completed + screened out)/(completed + screened out + refused + non-contacted)) was 37.3%.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics for sample population, New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Educational Attainment | 3923 | |

| Less than high school | 508 | 13 |

| High school or GED | 923 | 24 |

| Some college/vocational school | 879 | 22 |

| College graduate | 883 | 23 |

| Graduate work | 730 | 19 |

| Gender | 4000 | |

| Female | 2120 | 53 |

| Male | 1880 | 47 |

| Race | 3888 | |

| White | 1616 | 42 |

| Black or African American | 1055 | 27 |

| Asian | 164 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 958 | 25 |

| Other | 95 | 2 |

| Age (years) | 3960 | |

| 18-24 | 350 | 9 |

| 25-34 | 685 | 17 |

| 35-44 | 815 | 21 |

| 45-54 | 808 | 20 |

| 55-64 | 612 | 15 |

| 65+ | 690 | 17 |

| Marital Status | 3943 | |

| Married | 1632 | 41 |

| Divorced | 479 | 12 |

| Separated | 208 | 5 |

| Widowed | 354 | 9 |

| Never been married | 1270 | 32 |

| Annual Household Income | 3307 | |

| <= $40,000 | 1605 | 47 |

| $40,001-$80,000 | 1093 | 32 |

| > $80,000 | 722 | 21 |

| Drinking Before Moved to Neighborhood | 4000 | |

| No | 1346 | 34 |

| Yes, < 12 drinks/yr | 706 | 18 |

| Yes, >= 12 drinks/yr | 1948 | 49 |

| Student | 4000 | |

| No | 3881 | 97 |

| Yes | 119 | 3 |

Education Gini values ranged from 0.09 to 0.26, with a median value of 0.16. Neighborhoods with low education inequality tended to have higher mean educational attainment and median income (table 2). Respondents living in neighborhoods with low education inequality were more likely to report higher levels of individual educational attainment and annual household income, being White or Black, not being Hispanic, and using alcohol prior to moving to their neighborhoods of residence. They also tended to be older and were somewhat more likely to report being married.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics for sample population by 2000 education Gini, New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005

| Low Education Inequalitya | High Education Inequality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood characteristicsb | Median | Range | Median | Range | ||

| Education Gini | 0.13 | 0.09–0.16 | 0.19 | 0.16–0.26 | ||

| Mean educational attainment (years) | 13.1 | 11.6–16.1 | 11.7 | 10.1–13.5 | ||

| Median household income | $47,390 | $18,750–$79,475 | $28,745 | $16,000–$43,480 | ||

| Income Gini | 0.45 | 0.37-0.49 | 0.46 | 0.41-0.51 | ||

| Individual Characteristicsc | N | % | N | % | X2 | p |

| Educational attainment | 2,075 | 1,857 | 78.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 199 | 10 | 347 | 19 | ||

| High school or GED | 420 | 24 | 481 | 26 | ||

| Some college/vocational school | 472 | 23 | 441 | 24 | ||

| College graduate | 497 | 24 | 354 | 19 | ||

| Graduate work | 417 | 20 | 235 | 13 | ||

| Gender | 2,114 | 1,886 | 0.9 | 0.34 | ||

| Female | 1,064 | 50 | 981 | 52 | ||

| Male | 1,051 | 50 | 905 | 48 | ||

| Race | 2,056 | 1,851 | 283.4 | <0.001 | ||

| White | 960 | 47 | 532 | 29 | ||

| Black or African American | 655 | 32 | 401 | 22 | ||

| Hispanic | 293 | 14 | 769 | 42 | ||

| Asian | 83 | 4 | 116 | 6 | ||

| Other | 64 | 3 | 34 | 2 | ||

| Age (years) | 2,098 | 1,872 | 21.7 | 0.001 | ||

| 18-24 | 231 | 11 | 237 | 13 | ||

| 25-34 | 336 | 16 | 381 | 20 | ||

| 35-44 | 402 | 19 | 372 | 20 | ||

| 45-54 | 458 | 22 | 392 | 21 | ||

| 55-64 | 330 | 16 | 260 | 14 | ||

| 65+ | 341 | 16 | 231 | 12 | ||

| Marital status | 2,089 | 1,867 | 27.7 | <0.001 | ||

| Married | 1,038 | 50 | 834 | 45 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 259 | 12 | 306 | 17 | ||

| Widowed | 147 | 7 | 118 | 6 | ||

| Never been married | 646 | 31 | 610 | 33 | ||

| Annual household income | 2,114 | 1,886 | 147.0 | <0.001 | ||

| <= $40,000 | 645 | 30 | 943 | 50 | ||

| $40,001-$80,000 | 646 | 31 | 446 | 24 | ||

| > $80,000 | 509 | 24 | 229 | 12 | ||

| Missing | 315 | 15 | 267 | 14 | ||

| Drinking before moved to neighborhood | 2,114 | 1,886 | 26.3 | <0.001 | ||

| < 12 drinks/yr | 1,055 | 50 | 1,112 | 59 | ||

| >= 12 drinks/yr | 1,060 | 50 | 774 | 41 | ||

| Student | 2,114 | 1,886 | 2.4 | 0.12 | ||

| No | 2,044 | 97 | 1,800 | 95 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 3 | 85 | 5 | ||

Neighborhoods with 2000 Education Gini value at or below the median value for all neighborhoods.

Data from 2000 U.S. Census.

All individual-level sample sizes and percentages are weighted.

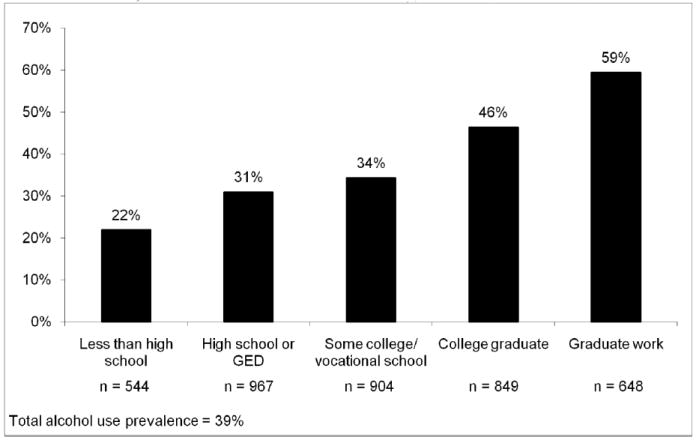

Thirty-nine percent of the respondents reported being drinkers. Overall alcohol-use prevalence varied markedly by individual educational attainment (figure 1). Twenty-two percent of respondents with less than a high school degree reported using alcohol; the proportion of drinkers was higher with each successive level of educational attainment, reaching 59% among respondents who had completed some graduate-level work. The mean number of drinks consumed per day among drinkers was inversely related to education level, ranging from 1.0 (standard deviation 1.8) among drinkers with less than a high school education to 0.6 (standard deviation 1.0) among drinkers who had completed some graduate-level work.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of alcohol use in the past 12 months by individual educational attainment levels, New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005. Alcohol use was self-reported and was defined as drinking 12 or more drinks in the past 12 months.

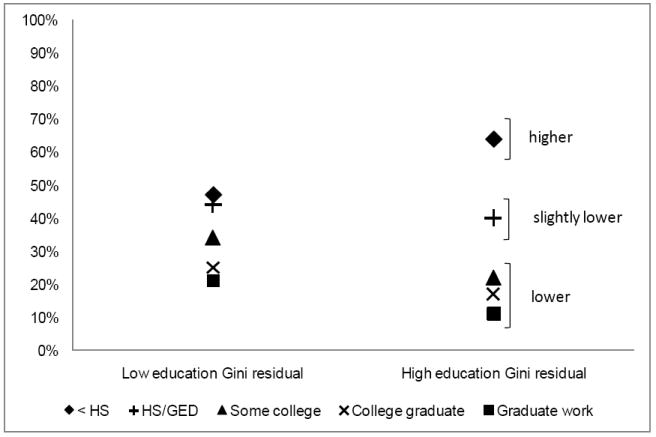

The proportion of respondents in a neighborhood reporting that they felt it was unacceptable for an adult to drink alcoholic beverages ranged from 3% to 61%, with a median of 34%. Restrictive drinking norms were slightly higher in neighborhoods with low education inequality (adjusting for mean educational attainment) than in ones with high education inequality (35% vs. 30%). Subgroup-specific restrictive drinking norms were stronger for lower education levels and were more divergent in neighborhoods with higher education inequality (figure 2). The average number of residents contributing to the subgroup-specific neighborhood norms variable varied from 9 among respondents with less than a high school degree to 16 among respondents with a high school degree but no further education.

Figure 2.

Average neighborhood proportion of respondents reporting they feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol, by neighborhood education Gini residual and individual education levels, New York Social Environment Survey, New York, New York, 2005. A high education Gini residual indicates a wider education distribution per level of neighborhood mean educational attainment, while a low education Gini residual indicates a narrower education distribution per level of neighborhood mean educational attainment. Respondents with higher education levels were less likely to report restrictive individual drinking norms. This pattern was more pronounced in neighborhoods with high education inequality than in neighborhoods with low education inequality.

The analysis of the relation between neighborhood education inequality and overall alcohol use prevalence is presented in table 3 (GEE logistic regression models). In the first adjusted model (model 2), one-standard-deviation-higher education inequality was associated with 1.18 times higher odds of alcohol use (odds ratio (OR) = 1.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08–1.30). There was no attenuation of the association when neighborhood-wide restrictive drinking norms were included (model 3: OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.11–1.32), nor with the additional inclusion of education-specific neighborhood norms (model 4: OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.12–1.34).

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) from general estimating equation logistic regression models of alcohol use (consumption of at least 12 drinks in past 12 months), New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N | 3,911 | 3,896 | 3,896 | 3,889 | ||||

| Covariate | OR | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI | ORa | 95% CI |

| Neighborhood-level | ||||||||

| Mean educational attainment-adjusted education Gini (per standard deviation) | 1.38 | (1.19, 1.59) | 1.18 | (1.08, 1.30) | 1.21 | (1.11, 1.32) | 1.23 | (1.12, 1.34) |

| Median incomeb,g | 0.98 | (0.91, 1.06) | 0.87 | (0.80, 0.96) | 0.89 | (0.82, 0.97) | ||

| Income Ginic | 1.18 | (0.91, 1.55) | 1.00 | (0.78, 1.29) | 1.00 | (0.80, 1.27) | ||

| Restrictive drinking normsd | 0.88 | (0.80, 0.96) | 1.01 | (0.90, 1.12) | ||||

| Education-specific restrictive drinking normse | 0.85 | (0.79, 0.92) | ||||||

| Individual-level | ||||||||

| Educational attainment level (vs. less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school/GED | 1.22 | (0.89, 1.67) | 1.19 | (0.88, 1.63) | 1.00 | (0.74, 1.35) | ||

| Some college/vocational school | 1.26 | (0.90, 1.76) | 1.24 | (0.89, 1.73) | 0.87 | (0.63, 1.20) | ||

| College graduate | 1.45 | (1.03, 2.05) | 1.43 | (1.02, 2.00) | 0.93 | (0.65, 1.34) | ||

| Graduate-level work | 1.99 | (1.39, 2.86) | 1.98 | (1.39, 2.82) | 1.17 | (0.78, 1.75) | ||

| Male gender (vs. female) | 2.15 | (1.84, 2.51) | 2.15 | (1.84, 2.52) | 2.16 | (1.86, 2.53) | ||

| Race (vs. White) | ||||||||

| Asian | 0.31 | (0.21, 0.46) | 0.31 | (0.21, 0.47) | 0.31 | (0.21, 0.46) | ||

| Black | 0.49 | (0.39, 0.60) | 0.51 | (0.43, 0.62) | 0.52 | (0.43, 0.63) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.41 | (0.32, 0.52) | 0.42 | (0.33, 0.54) | 0.43 | (0.34, 0.55) | ||

| Other | 0.54 | (0.24, 1.22) | 0.58 | (0.26, 1.31) | 0.59 | (0.25, 1.36) | ||

| Agef | 0.98 | (0.98, 1.00) | 0.98 | (0.98, 0.99) | 0.98 | (0.97, 1.00) | ||

| Incomeg (vs. < $40,000) | ||||||||

| $40,000-$80,000 | 1.47 | (1.19, 1.82) | 1.47 | (1.19, 1.81) | 1.44 | (1.17, 1.78) | ||

| >$80,000 | 1.61 | (1.16, 2.24) | 1.61 | (1.16, 2.24) | 1.62 | (1.17, 2.24) | ||

| Missing | 0.95 | (0.70, 1.28) | 0.95 | (0.70, 1.28) | 0.96 | (0.71, 1.30) | ||

| Marital status (vs. married) | ||||||||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.22 | (0.97, 1.54) | 1.21 | (0.96, 1.53) | 1.19 | (0.95, 1.49) | ||

| Widowed | 1.18 | (0.78, 1.78) | 1.18 | (0.78, 1.78) | 1.21 | (0.80, 1.82) | ||

| Never married | 1.33 | (1.10, 1.60) | 1.32 | (1.09, 1.60) | 1.30 | (1.07, 1.57) | ||

| Drinking before moving to neighborhood (vs. < 12 drinks/yr) | 5.37 | (4.32, 6.67) | 5.32 | (4.29, 6.59) | 5.27 | (4.26, 6.53) | ||

| Student (vs. nonstudent) | 0.87 | (0.47, 1.60) | 0.87 | (0.47, 1.60) | 0.87 | (0.47, 1.61) | ||

Mutually adjusted

For a $10,000 increase from median value of $36,470. Coefficients for unsquared and squared terms are model 2: -0.3, 0.2; model 3: -0.17, 0.4; model 4: -0.15, 0.03.

For a 0.05 increase from median value of 0.45. Coefficients for unsquared and squared terms per 0.01 increase are model 2: 0.01, 0.01; model 3: -0.02, 0.005; model 4: -0.02, 0.005.

Proportion of respondents in neighborhood who feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol.

Proportion of respondents in neighborhood who share the index respondent's education level and feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol.

For a one-year increase from median value of 50.5. Coefficients for unsquared and squared terms are -0.02, 0.0003 for models 2, 3, 4.

Annual household income

The strength of the association between education inequality and overall alcohol use tended to increase with higher individual educational attainment (table 4(a)). There was no significant association between education inequality and overall alcohol use among the respondents with less than a high school education (model 2: OR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.66–1.16). In the other four groups there was evidence that higher education inequality was associated with higher odds of alcohol use, although the results were at borderline levels of standard statistical significance. Among respondents who completed each level of education, adjusted ORs for a one-standard-deviation-higher education Gini value were OR = 1.24 (95% CI 0.97–1.59) for high school or a GED, OR = 1.27 (95% CI 0.99–1.62) for some college work, OR = 1.32 (95% CI 1.03–1.69) for a completed college degree, and OR = 1.31 (95% CI 1.01–1.70) for graduate-level work. As in the unstratified models, these associations were not attenuated with the inclusion of drinking norms (models 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Measures of association (95% confidence intervals) for an increase in education Gini value of one standard deviation from general estimating equation regression models of drinking behavior by individual educational attainment, New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005

| (a) Odds ratios from logistic regression models of alcohol use in past 12 months | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | ||||||

| Educational attainment | Ne | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Unstratified | 3,889 | 1.38 | (1.19, 1.59) | 1.18 | (1.08, 1.30) | 1.21 | (1.11, 1.32) | 1.23 | (1.12, 1.34) |

| Less than high school | 539 | 0.72 | (0.56, 0.92) | 0.87 | (0.66, 1.16) | 0.87 | (0.64, 1.18) | 1.05 | (0.77, 1.42) |

| High school/GED | 965 | 1.09 | (0.89, 1.33) | 1.24 | (0.97, 1.59) | 1.26 | (0.99, 1.62) | 1.26 | (0.98, 1.61) |

| Some college | 900 | 1.12 | (0.95, 1.33) | 1.27 | (0.99, 1.62) | 1.29 | (1.03, 1.62) | 1.26 | (1.06, 1.50) |

| College graduate | 844 | 1.65 | (1.40, 1.94) | 1.32 | (1.03, 1.69) | 1.30 | (1.01, 1.68) | 1.30 | (1.00, 1.68) |

| Graduate-level work | 641 | 1.68 | (1.39, 2.03) | 1.31 | (1.01, 1.70) | 1.30 | (1.00, 1.68) | 1.33 | (1.00, 1.76) |

| (b) Relative rates from Poisson regression models of the average number of drinks consumed per day among alcohol users | |||||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | ||||||

| Educational attainment | Ne | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI |

| Unstratified | 1,502 | 0.92 | (0.84, 1.00) | 0.79 | (0.68, 0.92) | 0.79 | (0.69, 0.90) | 0.80 | (0.70, 0.91) |

| Less than high school | 119 | 0.75 | (0.55, 1.02) | 0.71 | (0.47, 1.08) | 0.67 | (0.43, 1.04) | 0.69 | (0.42, 1.13) |

| High school/GED | 298 | 1.05 | (0.83, 1.33) | 0.74 | (0.59, 0.94) | 0.75 | (0.59, 0.94) | 0.75 | (0.59, 0.95) |

| Some college | 310 | 0.89 | (0.76, 1.04) | 0.73 | (0.57, 0.95) | 0.73 | (0.57, 0.94) | 0.69 | (0.50, 0.96) |

| College graduate | 392 | 1.05 | (0.83, 1.34) | 0.80 | (0.52, 1.24) | 0.79 | (0.55, 1.13) | 0.78 | (0.55, 1.12) |

| Graduate-level work | 383 | 0.98 | (0.85, 1.14) | 0.99 | (0.81, 1.20) | 0.98 | (0.79, 1.21) | 0.93 | (0.74, 1.18) |

Adjusted for mean neighborhood educational attainment.

Model 1 + gender, race, age, income, marital status, student status, drinking before moving to neighborhood of residence, neighborhood median income, neighborhood income inequality

Model 2 + proportion of respondents in neighborhood who feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol

Model 3 + proportion of respondents in neighborhood who share the index respondent's education level and feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol

Weighted; for model 4 (most restricted model).

The analysis of the relation between neighborhood education inequality and average daily alcohol consumption among drinkers is presented in table 5 (GEE Poisson regression models). In the first adjusted model (model 2), one-standard-deviation-higher education inequality was associated with 0.79 times fewer average drinks per day (relative rate (RR) = 0.79, 95% CI 0.68–0.92). This association was not attenuated by inclusion of neighborhood-wide norms (model 3: RR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.90) or the additional inclusion of education-specific norms (model 4: RR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.91). In contrast to the results for overall alcohol use, the magnitude of the association between education inequality and average daily consumption tended to decrease with higher educational attainment, although CIs were wide due to small stratum-specific sample sizes. Adjusted relative rates for each education level were RR = 0.71 (95% CI 0.47–1.08) for less than high school, RR = 0.74 (95% CI 0.59–0.94) for high school or a GED, RR = 0.73 (95% CI 0.57–0.95) for some college work, RR = 0.80 (95% CI 0.52–1.24) for a college degree, and RR = 0.99 (95% CI 0.81–1.20) for graduate-level work (table 4(b), model 2). As in the unstratified models, these associations were not attenuated with the inclusion of drinking norms (models 3 and 4).

Table 5.

Relative rates (95% confidence intervals) from general estimating equation Poisson regression models of the average number of drinks consumed per day among alcohol users, New York Social Environment Study, New York, New York, 2005

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N | 1,507 | 1,503 | 1,503 | 1,502 | ||||

| Covariate | RR | 95% CI | RRa | 95% CI | RRa | 95% CI | RRa | 95% CI |

| Neighborhood-level | ||||||||

| Mean educational attainment-adjusted education Gini (per standard deviation) | 0.92 | (0.84, 1.00) | 0.79 | (0.68, 0.92) | 0.79 | (0.69, 0.90) | 0.80 | (0.70, 0.91) |

| Median incomeb (per $10,000) | 1.10 | (1.00, 1.20) | 1.00 | (0.89, 1.13) | 1.01 | (0.91, 1.13) | ||

| Income Ginic | 1.09 | (1.04, 1.13) | 1.07 | (1.02, 1.12) | 1.06 | (1.02, 1.11) | ||

| Restrictive drinking normsd | 0.88 | (0.76, 1.01) | 0.96 | (0.81, 1.13) | ||||

| Education-specific restrictive drinking normse | 0.90 | (0.82, 0.99) | ||||||

| Individual-level | ||||||||

| Educational attainment level (vs. less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school/GED | 0.98 | (0.63, 1.53) | 0.97 | (0.63, 1.51) | 0.91 | (0.59, 1.43) | ||

| Some college/vocational school | 0.96 | (0.62, 1.47) | 0.96 | (0.62, 1.48) | 0.78 | (0.53, 1.15) | ||

| College graduate | 0.83 | (0.55, 1.25) | 0.83 | (0.55, 1.26) | 0.66 | (0.43, 1.02) | ||

| Graduate-level work | 0.65 | (0.40, 1.05) | 0.66 | (0.41, 1.05) | 0.49 | (0.31, 0.79) | ||

| Male gender (vs. female) | 1.72 | (1.39, 2.12) | 1.73 | (1.40, 2.15) | 1.73 | (1.40, 2.15) | ||

| Race (vs. White) | ||||||||

| Asian | 1.30 | (0.56, 3.01) | 1.29 | (0.55, 3.01) | 1.27 | (0.54, 2.95) | ||

| Black | 0.88 | (0.63, 1.22) | 0.91 | (0.67, 1.25) | 0.92 | (0.67, 1.27) | ||

| Hispanic | 1.12 | (0.84, 1.48) | 1.18 | (0.88, 1.58) | 1.19 | (0.89, 1.59) | ||

| Other | 1.01 | (0.50, 2.06) | 1.05 | (0.51, 2.14) | 1.07 | (0.52, 2.19) | ||

| Age (per year) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.01) | ||

| Incomeb (vs. < $40,000) | ||||||||

| $40,000-$80,000 | 1.03 | (0.78, 1.36) | 1.02 | (0.78, 1.34) | 1.01 | (0.77, 1.32) | ||

| >$80,000 | 1.11 | (0.79, 1.56) | 1.10 | (0.78, 1.54) | 1.11 | (0.80, 1.54) | ||

| Missing | 1.12 | (0.86, 1.46) | 1.10 | (0.85, 1.43) | 1.11 | (0.86, 1.43) | ||

| Marital status (vs. married) | ||||||||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.46 | (0.96, 2.22) | 1.47 | (0.96, 2.24) | 1.47 | (0.96, 2.24) | ||

| Widowed | 1.54 | (0.97, 2.45) | 1.53 | (0.95, 2.46) | 1.55 | (0.97, 2.48) | ||

| Never married | 1.59 | (1.26, 2.01) | 1.58 | (1.25, 2.00) | 1.56 | (1.24, 1.97) | ||

| Drinking before moving to neighborhood (vs. < 12 drinks/yr) | 1.55 | (1.22, 1.98) | 1.56 | (1.23, 1.98) | 1.57 | (1.23, 2.00) | ||

| Student (vs. nonstudent) | 0.91 | (0.59, 1.40) | 0.93 | (0.61, 1.41) | 0.93 | (0.63, 1.39) | ||

Mutually adjusted

Annual household income

Rescaled to range from 0–100.

Proportion of respondents in neighborhood who feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol.

Proportion of respondents in neighborhood who share the index respondent's education level and feel it is unacceptable for adults to drink alcohol.

4. Discussion

In an analysis of data from a population-representative survey of residents of New York City, neighborhood-level education inequality was positively associated with alcohol-use prevalence and negatively associated with average daily alcohol consumption among drinkers. While the strength of the association with alcohol-use prevalence tended to increase with increasing individual educational attainment, the strength of the association with the level of alcohol consumption among drinkers tended to decrease with increasing individual educational attainment. None of the associations between education inequality and drinking behavior were attenuated when overall and education-subgroup-specific neighborhood drinking norms were included in models.

Our results provide further evidence of a relation between education inequality and drinking behavior but underscore its complexity. Neighborhood drinking norms varied with education inequality, such that neighborhoods with lower education inequality (after accounting for mean education) had more restrictive norms. Norms in educational attainment subgroups within neighborhoods suggested an interesting pattern of a wider disparity in norms accompanying higher education inequality: higher education inequality was related to more restrictive norms among the subgroup with the lowest education level but more permissive norms among subgroups with higher education levels. This suggests that contact within a neighborhood between groups with different norms leads to a strengthening of typical norms in those subgroups. Despite these interesting patterns, education-subgroup norms did not appear to mediate the relation between education inequality and the drinking outcomes.

Future research examining other potential mechanisms may help us better understand the relations between education inequality and drinking behavior. In light of the differences between education subgroups suggested by our results, research should consider how these mechanisms might differentially affect people with different education levels. For example, education inequality may influence drinking behavior by affecting the density or type of alcohol-selling establishments in the neighborhood (Galea et al., 2007a; Schonlau et al., 2008). In New York City, socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods have fewer liquor stores but a higher overall density of alcohol-selling establishments because of a higher density of bars and restaurants (Galea et al., 2007a). The presence of some highly educated residents may therefore result in fewer liquor stores in a neighborhood but more bars and restaurants catering to these residents. Any resulting effect on alcohol use would depend on how residents used the different types of establishments (Gruenewald, 2007).

Higher education inequality may also indirectly mitigate psychological stress from physical or social disorder in disadvantaged neighborhoods that can contribute to heavy drinking among residents (Bernstein et al., 2007; Hill and Angel, 2005; Mulia et al., 2008). More highly educated individuals may have greater access to individuals in power and be more able to successfully navigate social and political institutions, securing improvements such as better recreational facilities, transportation service, and infrastructure (Galea and Ahern, 2005; Galea et al., 2007a) that would be shared by all neighborhood residents. This mechanism is supported by our finding of an inverse association between education inequality and average daily alcohol consumption, with the association tending to be more pronounced among subgroups with lower education levels.

It may also be informative to consider measures of perceived inequality. Residents’ perceptions of the neighborhood social environment, and the environment’s possible effects on their health, may be influenced not only by inequality as measured objectively but by residents’ perceived socioeconomic standing relative to their neighbors (Schieman and Pearlin, 2006).

There are several limitations to this analysis. Response bias is a concern in any population-level survey; however, participation rates in this study were comparable to other major large population-based studies and the study population for this study was demographically similar to the general population of New York City (Galea and Tracy, 2007). Respondents may also have underreported alcohol use, although substance use may tend to be less underreported during phone interviews than in person (Midanik et al., 2001). If alcohol use was underreported to a similar extent across all neighborhoods, any relations would likely be underestimated in this analysis. Because of the cross-sectional design of this study, it is not possible to definitively ascertain whether respondents’ drinking habits predated their residence in their neighborhoods. However, because we were able to control for past drinking behavior, the results are less likely to have been affected by social selection processes than would otherwise have been the case. Norms were measured in just one of many possible ways, and the group drinking norm variables were calculated from questions originally designed to assess individual norms. Finally, there are some limitations to the generalizability of this analysis since the study sample comprises residents of a single city: drinking behavior and its determinants may differ between regions and between rural and urban areas (Naimi et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2004; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008).

The results of this analysis are consistent with those of Galea and Ahern (2005) and Galea et al. (2007a) and extend this previous research in two ways. They suggest that the relation between neighborhood education inequality and health may vary with individual educational attainment. They also suggest that mediators other than drinking norms likely explain the relation between education inequality and drinking behavior. Future research could fruitfully consider other potential mediators. Different mediators may operate differently among neighborhood subpopulations, and more than one mediator may be acting at the same time. Therefore, research that considers multiple mechanisms and their combined effects may be most informative. Our results also provide further evidence that the relation between education inequality and health is independent of and differs from the relation between income inequality and health. While our analysis does not lead to immediate policy recommendations, research that identifies characteristics that affect neighborhood population health, as well as the mechanisms through which they operate, is important to increasing understanding of the processes underlying population health and to informing the development of approaches to improve it.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Affairs. 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern J, Galea S, Hubbard A, Midanik L, Syme SL. “Culture of drinking” and individual problems with alcohol use. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1041–1049. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield J. Does income inequality harm health? New cross-national evidence. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:231–248. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KT, Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Vlahov D. The built environment and alcohol consumption in urban neighborhoods. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in situational norms and attitudes toward drinking among whites, blacks, and hispanics: 1984-1995. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Li YS, Wu YH, Chao HJ. A multilevel analysis of neighborhood and individual effects on individual smoking and drinking in Taiwan. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly MC, Duncan GJ, Kaplan GA, Lynch JW. Macro-to-micro links in the relation between income inequality and mortality. Milbank Q. 1998;76:315–339. 303–314. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J. Distribution of education and population health: an ecological analysis of New York City neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:2198–2205. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Rudenstine S, Vlahov D. Education inequality and use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007a;90(Suppl 1):S4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Vlahov D. Neighborhood income and income distribution and the use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. Am J Prev Med. 2007b;32:S195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Room R. Situational norms for drinking and drunkenness: trends in the US adult population, 1979-1990. Addiction. 1997;92:33–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:870–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, Negassa A, deB Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations (GEE): an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop CL, Miller GE, Hill JS. Neighbourhood socioeconomics status predicts non-cardiovascular mortality in cardiac patients with access to universal health care. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Angel RJ. Neighborhood disorder, psychological distress, and heavy drinking. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn HS, Patel AV, Jacobs EJ, Calle EE, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. Pathways between area-level income inequality and increased mortality in U.S. men. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:332–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla A, Zhou K, Reuben D, Greendale G, Moore A. Longitudinal trajectories of heavy drinking in adults in the United States of America. Addiction. 2006;101:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:215–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modelling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009;104:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, Howes MJ, Jin R, Vega WA, Walters EE, Wang P, Zaslavsky A, Zheng H. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Kaysen DL, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Lewis MA, Dillworth T, Montoya HD, Neighbors C. Evaluating level of specificity of normative referents in relation to personal drinking behavior. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009:115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg ML, Amsterdam EA. Alcohol, wine, and cardiovascular health. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:347–351. doi: 10.1002/clc.20263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J, Smith GD, Harper S, Hillemeier M, Ross N, Kaplan GA, Wolfson M. Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1 A systematic review. Milbank Q. 2004;82:5–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Reports of alcohol-related harm: telephone versus face-to-face interviews. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:74–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Gould R, Reuben DB, Greendale GA, Carter MK, Zhou K, Karlamangla A. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:458–465. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Schmidt L, Bond J, Jacobs L, Korcha R. Stress, social support and problem drinking among women in poverty. Addiction. 2008;103:1283–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Bolen J, Wells HE. Metropolitan-area estimates of binge drinking in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:663–671. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of City Planning. Community District Profiles. New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen ML, Sinisi SE, van der Laan MJ. Estimation of direct causal effects. Epidemiology. 2006;17:276–284. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000208475.99429.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Wu C-L. The links between education and health. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pearlin LI. Neighborhood disadvantage, social comparisons, and the subjective assessment of ambient problems in older adults. Soc Psychol Q. 2006;69:253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Schonlau M, Scribner RA, Farley TA, Theall KP, Bluthenthal RN, Scott M, Cohen DA. Alcohol outlet density and alcohol consumption in Los Angeles county and southern Louisiana. Geospatial Health. 2008;3:91–101. doi: 10.4081/gh.2008.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Clarke P, Marmot M. Multiple measures of socio-economic position and psychosocial health: proximal and distal measures. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1192–1199. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1192. discussion 1199-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standridge JB, Zylstra RG, Adams SM. Alcohol consumption: an overview of benefits and risks. South Med J. 2004;97:664–672. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Kawachi I. Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [November 10 2009];National Survey on Drug Use & Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. NSDUH Series H-34. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V, Wang Y, Fan X. Policy Research Working Paper Series. The World Bank; Washington, D.C: 2000. Measuring Education Inequality: Gini Coefficients of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG. The epidemiological transition: from material scarcity to social disadvantage. Daedalus. 1994;123:61–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1768–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:816–820. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]