Abstract

This study investigated the extent to which bilingual counselors initiated informal discussions about topics that were unrelated to the treatment of their monolingual Spanish-speaking Hispanic clients in a National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trial Network protocol examining the effectiveness of motivational enhancement therapy (MET). Session audiotapes were independently rated to assess counselor treatment fidelity and the incidence of informal discussions. Eighty-three percent of the 23 counselors participating in the trial initiated informal discussions at least once in one or more of their sessions. Counselors delivering MET in the trial initiated informal discussion significantly less often than the counselors delivering standard treatment. Counselors delivering standard treatment were likely to talk informally the most when they were ethnically non-Latin. Additionally, informal discussion was found to have significant inverse correlations with client motivation to reduce substance use and client retention in treatment. These results suggest that informal discussion may have adverse consequences on Hispanic clients’ motivation for change and substance abuse treatment outcomes and that maintaining a more formal relationship in early treatment sessions may work best with Hispanic clients. Careful counselor training and supervision in MET may suppress the tendency of counselors to talk informally in sessions.

Keywords: self-disclosure, therapeutic alliance, motivational interviewing, motivational enhancement therapy, treatment integrity, adherence and competence, substance abuse treatment, Hispanic population

1. Introduction

According to the 2007 Census report, Hispanics are the largest and fastest growing ethnic minority population in the U.S., with accelerating rates of substance abuse (Warner, Valdez, Vega et al., 2006), a disproportionate level of substance-related adverse outcomes (Amaro, Arevalo, Gonzalez, Szapocznik, & Iguchi, 2006; Caetano, 2003), and a propensity to underutilize mental health and substance abuse treatment services (Wells, Klap, Koike & Sherbourne, 2001). The implementation of high quality behavioral health services for Hispanics that are empirically supported and linguistically and culturally competent is a major challenge to the field (Añez, Paris, Bedregal, Davidson, & Grilo, 2005; Gloria & Peregoy, 1996; Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992; Volkow, 2006).

Motivational enhancement therapy (MET; Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992) is a manual-guided version of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) that has received substantial empirical support. Several meta-analyses have shown that MET has small to moderate treatment effects (.2 to .5) for substance use disorders (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Lundhal, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010), and it has been adapted to treat a wide variety of psychiatric issues (Arkowitz, Westra, Miller, & Rollnick, 2008) and health-related behavior problem areas (Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008). This brief treatment involves the use of empathic counseling techniques (such as reflective listening) and strategies for eliciting client self-motivational statements (such as assessment feedback to produce discomfort with status quo behaviors) to enhance a client’s intrinsic motivation for positive behavioral change.

Recently, the effectiveness of MET was tested in two separate protocols within the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN; Hanson, Leshner, & Tai, 2002), one delivered to primary English speakers (Ball et al., 2007) and one delivered solely to monolingual Spanish speakers (Carroll et al., 2009). Identical in most ways (other than language and relevant cultural adaptations), both protocols examined the effectiveness of a three-session MET intervention to counseling-as-usual (CAU) in five U.S.-based community substance abuse treatment programs. Within the Spanish MET protocol, the MET manual and all assessments were translated into Spanish, and counselors delivered both treatment conditions entirely in Spanish. All clinical and research staff participating in the study were bilingual and most were of Hispanic descent (Suarez-Morales et al., 2007). Outcomes in the English and Spanish MET trials were similar. While both the MET and CAU interventions resulted in reductions in substance use during the 4-week treatment phase, MET resulted in sustained reductions during the subsequent 12 weeks of the study, whereas CAU was associated with increases in substance use over this follow-up period. Relative to CAU, MET led to a greater reduction in frequency of alcohol use in the subgroup of participants whose primary substance was alcohol (see Ball et al., 2007 and Carroll et al., 2009).

Counselors who delivered MET in both protocols received extensive training and supervision and successfully delivered MET with significantly higher adherence (frequent use of MI consistent strategies) and competence (skillful implementation) than the CAU counselors across the three sessions (see Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2008 and Santa Ana et al., 2009 for details). An interesting caveat to these integrity findings within the English MET protocol was that CAU counselors talked more often with their clients about issues that were unrelated to the clients’ treatment needs and this higher frequency of informal discussion (i.e., ‘chat’) was significantly related to less counselor MET adherence and competence and less in-session change in client motivation, though unrelated to client program retention and substance use outcomes (Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2009). The findings suggested that too much informal discussion in sessions may have hindered the counselors’ proficient implementation of MET and the clients’ motivational enhancement process and that formal training in MET may have suppressed the tendency of counselors to talk informally in sessions (Martino et al., 2009).

Although some researchers have found that informal discussion involving self-disclosure may help strengthen emotional bonds and therapeutic alliance (Goldfried, Burckell, & Eubanks-Carter, 2003; Hill & Knox, 2001) and establish an egalitarian relationship which empowers clients to change (Simi & Mahalik, 1997), other researchers have found results similar to those reported by Martino and colleagues (2009). This research highlights the potential negative effects of informal discussion when counselors share personal information with their clients that is not directly related to treatment. These discussions have been found to disrupt therapeutic alliance (Multon, Ellis-Kalton, Heppner, & Gysbers, 2003) and clients’ further disclosure about their health concerns (McDaniel et al., 2007). No previous studies have evaluated the role of counselor-initiated informal discussion in the delivery of empirically supported treatments with Spanish-speaking substance users.

The frequency and function of informal discussion in treatments tailored for Hispanic clients may differ from that which occurs in treatments for non-Hispanics, although the direction of this relationship is unclear as well. Atdjian and Vega (2005) have recommended that counselors fortify their therapeutic alliance with Hispanic clients early in treatment by attending to Hispanic cultural values of confianza and personalismo that characterize the building of personal relationships among many Hispanics. Confianza refers to the importance of establishing trust and confidence early in personal relationships (Torres, 2000). Personalismo is a style of communication that emphasizes warmth and an overall preference for relationships with individuals rather than institutions. Añez and colleagues (2005) note that appropriate self-disclosure, which can include “small talk” about hobbies, country of origin and favorite foods, might function to tap both of these valued experiences. The absence of informal discussion risks that the client might perceive the counselor as frío (cold) or antipático (unpleasant) (Añez et al., 2005).

On the other hand, formalismo and respeto are two additional cultural values that guide the interactions of counselors with their Hispanic clients (Añez, Silva, Paris, Bedregal, 2008, Interian, Díaz-Martínez, 2007). Many Hispanics value formality and respect and consequently stress the importance of hierarchical relationships in which persons should be addressed formally (formalismo) and with deference (respeto). Formalismo is likely related to Cherbosque’s (1987) finding that Mexicans rated non self-disclosing counselors as more trustworthy and expert than counselors who self-disclosed. In another study, Ruiz (1995) notes that since professionals are generally held in such high regard by Hispanics, it is advisable that counselors dress and speak appropriately, including limiting inappropriate informal dialogue, which might be perceived as unprofessional by their clients.

Also unexamined is the extent to which ethnic and cultural characteristics of the counselors influence the frequency of informal discussion during sessions. Past studies have shown that Hispanic clients may view counselors with similar ethnic backgrounds favorably (Alegría et al., 2006; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991). Moreover, similarities in acculturation, a bidimensional process whereby an individual adjusts and integrates features of both the original (Hispanic) and dominant (American) cultures (LaFramboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993; Tadmor & Tetlock, 2006), between counselors and clients might heighten the relationship-building capacity of treatment and influence the degree to which counselors talk informally with their Hispanic clients. To the extent that informal discussion acts as a culturally facilitative condition, Hispanic counselors or counselors acculturated to Hispanic customs might talk more informally with their Hispanic clients and support the broader motivational enhancement process used in MET. Alternatively, if informal interaction compromises relationship building in early treatment sessions with Hispanic clients, too much of it may hinder the counselors’ proficient implementation of MET treatment strategies and careful training in MET might be needed to reduce the extent to which counselors talk informally, as occurred in the English MET trial (Martino et al., 2009).

To address these issues, we examined the extent to which community program bilingual counselors talked informally with their Hispanic clients and how certain cultural factors affected informal discussions within the CTN Spanish MET protocol (Carroll et al., 2009). First, we examined the frequency and content of informal discussions. Second, we analyzed how differences between those counselors who had been randomized to learn and be supervised in MET throughout the trial versus those who had been randomized to deliver standard treatment may have influenced the amount of informal discussion in sessions. As in the English MET trial, we predicted that counselors trained in MET would have a lower level of informal discussions than CAU counselors. Third, given the uncertain relationship informal discussion and treatment processes and outcomes are predicted to have with Hispanic clients in the literature, we explored the relationship between counselor-initiated informal discussion and MET adherence and competence, client change in motivation, therapeutic alliance, and primary treatment outcomes (client retention, substance use). We also explored the relationship between informal discussions and a) counselor ethnicity, b) counselor-client ethnic matching, and c) acculturation levels.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 23 bilingual counselors participated in the Spanish MET protocol. All counselors were employed in one of five licensed outpatient substance abuse treatment programs that provided an array of services for English-and Spanish-speaking clients. Each program had a minimum of four Spanish-speaking counselors on staff who delivered substance abuse treatment in Spanish to Hispanic clients. Details on counselor inclusion/exclusion criteria, procedures to ensure counselor Spanish language fluency and comprehension, and counselor characteristics and demographic information are presented in prior reports (Carroll et al., 2009; Suarez-Morales et al., 2007). Counselors were ineligible to participate in the protocol if they did not pass a Spanish fluency test or had received formal MET training 3 months prior to protocol initiation, a timeframe in which MET skills are likely to diminish without ongoing performance feedback and coaching (Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004). Counselors provided either written permission or informed consent depending on local Institutional Review Board requirements and were randomized to the MET or CAU condition to balance levels of interest and commitment to the protocol and prior knowledge of MI.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Counselor treatment adherence and competence

The Independent Tape Rater Scale (ITRS; Martino et al., 2008) includes 30 items that assess community program counselors’ adherence and competence within three broad categories of therapeutic strategies; namely, those consistent with MET, inconsistent with MET (e.g., direct confrontation), or common to drug counseling (e.g., assessing substance use). One item captures instances in which counselors initiate conversation with clients about topics that are not related to the problems for which the client entered treatment or make self-disclosures unrelated to the counselors’ personal recovery history (i.e., indicator of informal discussion). This item excludes counselors’ disclosures about their recovery history because these disclosures often are considered appropriate in general drug counseling (Mallow, 1998). The scale also includes general ratings of the counselor (overall therapeutic skillfulness and ability to maintain a consistent structure/therapeutic approach) and assessment of the client’s level of motivation at the beginning (first 5 minutes) and end of the session (last 5 minutes).

For the 30 therapeutic strategy items, raters evaluate the counselors on two dimensions using a 7-point Likert scale. First, they rate the extent to which the counselor delivered the intervention (adherence; 1 = not at all, to 7 = extensively). Second, they rate the skill with which the counselor delivered the intervention (competence; 1 = very poor, to 7 = excellent). The informal discussion item, general counselor, and client motivation items were rated using 7-point Likert scales (low, to high). Thus, informal discussion was measured by the frequency of its use (adherence), not the competence in which it was rendered. Psychometric analyses of the ITRS used in the Spanish MET trial (Santa Ana et al., 2009) and the English MET trial (Martino et al., 2008) confirmed good to excellent levels of interrater reliability (ICCs ranging from .60 to .96 in the Spanish MET trial and from .66 to .99 in the English MET trial) and a two-factor model among the MET consistent items: a) fundamental skills that underpin the empathic and collaborative stance of MET such as open-ended questions, reflective statements, and motivational interviewing style or spirit; and b) advanced skills for evoking client motivation for behavior change, such as heightening discrepancies and change planning (Martino et al., 2008; Santa Ana et al., 2009).

2.2.2. Therapeutic alliance

The therapeutic alliance was measured using the counselor and client versions of the 19-item Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAq-II; Luborsky et al., 1996). A total score is derived from the HAq-II by summing the 19 items (each rated on a 1 to 6 scale), after reversing the scoring of negatively worded items. The range of possible scores is therefore 19 to 114, with high scores indicating a more positive alliance. Both counselors and participants completed the scale after the second session. When used with individuals with substance abuse, the scale has good reliability and construct validity (Cecero, Fenton, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2001).

2.2.3. Change in client motivation, retention and substance use outcomes

Client motivation was measured by the ITRS raters using a 7-point global rating scale at the beginning and end of the session to reflect the relative balance of client change talk and resistant statements. For instance, a score of 1 reflects no motivation to change primary substance use, and a score of 7 reflects extremely strong motivation for change. ICC interrater reliability for these ratings were very good (beginning = .77, end = .83). Change in client motivation was measured by subtracting the level of motivation demonstrated by the clients at the beginning of their protocol sessions from their level of motivation at the end of these sessions (range = −6 to 6). Research assistants collected client retention data (days of enrollment in program) based on self-reports and confirmed with program records. Detailed self-reports of alcohol and other drug use by week, from baseline through 16 continuous weekly data points (a 4-week treatment phase and 12-week follow-up period), were collected by means of the Timeline Follow-back method (Sobell & Sobell, 1992), a reliable and valid method for assessing substance use (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000). Self-report accuracy was checked by comparing reports with contiguously collected urine and breath screens; these comparisons indicated high correspondence (see Carroll et al., in 2009).

2.2.4. Counselor and client ethnicity and matching

Counselor ethnicity was indicated on the Therapist Characteristic Form, which gathered demographic information about the country of origin of the counselors, the clients and each of their parents, language use, and the individual’s length of residence (years) in the United States. Country of origin was measured by asking them to indicate their birthplace and served as the indicator of ethnicity in this study. A dichotomous birthplace variable was created for this study, coded 1 for all non-U.S. born Latin birthplaces (i.e., Mexico, U.S. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Cuba, Dominican Republic and several Spanish-speaking Central and South American countries) to indicate Latin-born counselors and coded 0 for a birthplace outside of Latin America (predominantly U.S.-born). Birthplace and self-reported ethnicity substantially overlapped and did not differ significantly (X2=.64, p = .42). Ethnic match was assigned if the client’s birthplace matched that of the counselor.

2.2.5. Counselor acculturation

The level of counselor acculturation to Hispanic and American cultures was determined using the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire (BIQ). The BIQ is a 24-item scale that assesses the individual’s level of involvement with either the Hispanic or Anglo-American cultures (Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980). The BIQ is one of the few bidimensional acculturation measures designed specifically for Hispanics (Zane & Mak, 2003). Half of the items are Hispanic-oriented and half are American-oriented. The items assess comfort with the English or Spanish language in specific settings (e.g., home, work, with friends) and enjoyment of American or Hispanic cultural activities. Items are answered using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all comfortable/not at all to 5 = very comfortable/very much). A score is computed for each cultural dimension (i.e., Americanism and Hispanicism). Cronbach’s alpha for Americanism and Hispanicism were .98 and .76, respectively (Suarez-Morales et al., in press). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses have supported the BIQ’s cultural dimensions (Xiaohui, Suarez-Morales, Schwartz, & Szapocznik, 2009).

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Counselor training and supervision

One of the principal goals of the MET protocols was to examine whether MET is effective when delivered by “real world” counselors (Carroll et al., 2002). As such, there were minimal training and education requirements of counselors to be eligible for participation in the study. As described in the main study report (Carroll et al., in 2009), recruitment of counselors only required that counselors be willing to participate in the research protocol, receive MET training and supervision, and agree to have their intakes taped and monitored. A simple randomization procedure was used to assign half the counselors to MET and half to CAU in an effort to balance the counselors’ levels of interest and commitment to the protocol and prior knowledge of MI. The counselors assigned to deliver MET in the trial received a 16-hour intensive workshop training, followed by audiotaped practice cases supervised by bilingual Spanish-speaking MET experts until they demonstrated minimal proficiency standards (i.e., at least half of the MET-consistent items rated average or above in terms of adherence and competence) in three sessions. After counselors were certified in MET, they began to treat randomized clients in the protocol and receive biweekly supervision from their supervisors who provided the counselors with MET adherence and competence rating-based feedback and coaching after reviewing audiotaped client sessions.

In addition, in the MET condition, supervisors encouraged counselors to address culturally specific issues that might inform the counselors’ understanding of the clients’ motivations to change their substance use. Thus, counselors and clients sometimes discussed issues such as migration (e.g., experience coming into the US), acculturation and stigma (e.g. language barriers, feeling disrespected by others), trauma history (e.g., leaving family behind, imprisonment), or obligations to family members residing outside of the United States to appreciate how these factors might affect the clients’ readiness to change. To not alter CAU practices, CAU counselors did not receive formal treatment training in the protocol. They continued to deliver individual drug counseling as they typically provided these services and to be clinically supervised in the manner usually conducted within each individual program/site.

2.3.2. Counselor Adherence/Competence Rating

Nine tape raters were trained in the methods used to evaluate the 325 session audiotapes generated within the protocol: MET (n=160) and CAU (n=165). The majority of tapes randomly selected for rating were from those participants who had attended all three sessions (about 70% of total sample) so that outcome analyses could examine counselor adherence and competence attempting to control for the possible confounding effect of the amount of treatment clients received. The remaining 30% of tapes selected for analysis came from participants who completed 1 to 2 sessions. This sample included all 23 counselors and 152 of the 379 (40.1%) clients who received at least one protocol session (see Santa Ana et al., 2009 for details about adherence and competence rating procedures).

2.3.3. Data analyses

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the associations between informal discussion frequency and continuous measures of counselor characteristics (overall skillfulness, preservation of therapeutic structure, acculturation), treatment process (therapeutic alliance, in-session change in client motivation) and outcomes (programs retention, primary drug abstinence). Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare the mean frequency of informal discussions between MET and CAU conditions, as well as to test the role of counselor ethnicity and counselor-client ethnicity match on the frequency of informal discussion. Additionally, Chi-squared tests were used to compare the proportion of sessions in which informal discussion occurred between MET and CAU conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Counselor characteristics

Characteristics of the 23 counselors are displayed in Table 1. They were predominantly female, Hispanic, and on average 38 years old. The counselors had been employed at their agencies for about 4 years. Around 44% of counselors had master’s degrees. On average, they completed 16 years of education. Twenty-seven percent of the counselors reported being in recovery. Sixty-five percent of counselors reported having some prior exposure to MI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Counselors Who Participated in Spanish MET Protocol

| Characteristics | Counselor (N = 23) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) female | 15 (65.2) |

| 1Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 6 (27.3) |

| Hispanic marked only | 8 (36.4) |

| Mexican | 2 (9.1) |

| Puerto Rican | 4 (18.2) |

| Other | 2 (9.1) |

| 2Place of birth, n (%) | |

| South American countries | 2 (12.5) |

| Other Central American countries | 1 (6.3) |

| Mexico | 2 (12.5) |

| United States | 5 (31.3) |

| Cuba | 1 (6.3) |

| Puerto Rico | 2 (12.5) |

| Dominican Republic | 2 (12.5) |

| Jamaica | 1 (6.3) |

| 3Counselor’s primary language, n (%) | |

| Spanish | 10 (62.5) |

| English | 5 (31.3) |

| Other | 1 (6.3) |

| 4Acculturation, M (SD) | |

| Hispanicism | 4.1 (.7) |

| Americanism | 4.5 (.8) |

| Primary treatment orientation, n (%) | |

| Twelve Step | 0 |

| CBT | 2 (8.7) |

| MI | 2 (8.7) |

| Psychodynamic | 2 (8.7) |

| Mixed | 17 (73.9) |

| Highest degree completed, n (%) | |

| High School | 3 (13) |

| Associates | 1 (4.3) |

| Bachelors | 6 (39.1) |

| Masters | 10 (43.5) |

| Self-report in recovery, n (%) | 5 (26.3) |

| Hold counselor/license certification, n (%) | 13 (56.5) |

| Prior MI experience, n (%) | 15 (65.2) |

| Hours of formal MI training, M (SD) | 7.9 (8.3) |

| Age, M (SD) | 38.1 (10.7) |

| Years of counseling experience, M (SD) | 6.3 (5.2) |

| Years of supervisory experience, M (SD) | 2.8 (3.1) |

| Years employed at agency, M (SD) | 3.9 (2.8) |

| Years of education, M (SD) | 15.6 (4.7) |

| Years held highest degree, M (SD) | 7.0 (6.4) |

One counselor elected not to report ethnicity, thus reducing sample to N = 22.

Counselors from one site did not complete Participant Characteristic Form, thus reducing sample to N = 16.

Counselors from one site did not complete Participant Characteristic Form, thus reducing sample to N = 16.

Acculturation measure possible range: 1 = not at all comfortable/not at all to 5 = very comfortable/very much.

3.2. How often did informal discussions occur?

Informal discussions were rated as occurring in 33% of all sessions evaluated (i.e., a rating of 2 or more on the ITRS adherence scale). Eighty-three percent (n = 19) of the counselors talked informally with clients at least once in a session. On average, these discussions occurred roughly once or twice per session (i.e., a mean ITRS score of 1.74, and SD = 1.30), about as often as counselors in the English MET trial (see Table 2). Similar to the English MET trial, 57% (n = 13) of the counselors had informal discussions three or more times in at least one of their evaluated sessions. Two counselors (9%) made informal comments in 75% or more of their sessions. Relative to therapeutic strategies used during the sessions, counselors talked informally with their clients less often than they used MET consistent strategies or techniques to assess substance use or related psychosocial factors. In contrast, on average informal discussion occurred more frequently than any of the MET inconsistent strategies (e.g., direct confrontation) or strategies involving treatment approaches from other theoretical orientations (e.g., coping skills training) (see Santa Ana et al., 2009 for details about ITRS item frequencies in the Spanish MET trial).

Table 2.

Comparison of the Spanish and English MET Trial Informal Discussion Frequency

| Category | Spanish MET | English MET |

|---|---|---|

| Sessions with informal discussion, n (%) | 107 (33) | 147 (35) |

| Counselors talking informally in ≥ 1 session, n (%) | 19 (83) | 32 (90) |

| Counselors talking informally ≥ 3 times in at least 1 session, n (%) |

13 (57) | 23(66) |

| Counselors talking informally in ≥ 75% of their sessions, n (%) |

2 (9) | 7 (20) |

| 1Frequency of informal discussion per session, M (SD) | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.87 (1.5) |

Note: The Spanish MET trial included 23 counselors and 325 audiotaped sessions (Santa Ana et al., 2009). The English MET trial included 35 counselors and 421 audiotaped sessions (Martino et al., 2008).

Informal discussion rating is on a 7-point Likert scale: 1=not at all, 2=a little (once), 3=infrequently (twice), 4=somewhat (3-4 times), 5=quite a bit (5-6 times), 6=considerably (> 6 times/more depth in interventions), 7=extensively (high frequency/characterizes entire session).

3.3. What was the content of the informal discussions?

To estimate what counselors informally discussed with their clients, we randomly selected one tape in which informal discussions occurred from each of the 23 counselors who received a rating of 2 or more. Sixty-two instances of informal discussion were transcribed from these tapes and then categorized by three Spanish-fluent authors (WB, LA, and MP) until they reached agreement on all transcriptions; results are presented in Table 3. The most commonly discussed topics include opinions unrelated to the client’s treatment (21%) which pertained to a variety of topics (e.g., religion, the cities in which they live), familial issues (10%), psychological/interpersonal issues or difficulties (10%) such as past struggles with depression, health issues (10%), and discussions related to cooking, favorites foods and eating out (10%). Counselors initiated other informal discussions in which they self-disclosed personal information (8%) such as current activities or plans. With somewhat less frequency, counselors discussed work-related issues or stressors (8%), topics relating to the job-market or the prices of common items (6%), information about their countries of origin (5%), and the weather (5%). Table 4 displays examples of these categories.

Table 3.

Categories of Informal Discussions in Sessions

| Categories | Overall occurrence, n (%) | Counselors involved, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Opinions not related to client’s treatment | 13 (21) | 9 (47) |

| Familial issues | 6 (10) | 4 (21) |

| Psychological/Interpersonal issues | 6 (10) | 2 (11) |

| Health issues | 6 (10) | 3 (15) |

| Cooking/Food | 6 (10) | 4 (21) |

| Personal information | 5 (8) | 5 (26) |

| Work-related issues | 5 (8) | 4 (21) |

| Job market/Bargains | 4 (6) | 4 (21) |

| Country of origin | 3 (5) | 2 (11) |

| Weather | 3 (5) | 3 (16) |

| Other | 5 (8) | 4 (26) |

Note: Categories were derived from a content assessment of the recorded counselor informal discussions transcribed from one randomly selected session from each of the 23 counselors in which informal discussion occurred. The percentages represent the proportion of informal discussion that falls in each category (overall occurrence) relative to the informal discussions across counselors in the sample (n = 62), as well as the proportion of total counselors who made informal discussions consistent with each category.

Table 4.

Informal Discussion Examples

| Categories | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal information | Client: | Mi hija no duerme bien, se levanta a menudo. (My daughter doesn’t sleep well. She gets up often.) |

| Counselor: | Yo también de chiquillo, no quería dormir, quería saber lo que estaba pasando. (I also when I was young didn’t want to sleep, I always wanted to know what was going on.) |

|

| Familial issues | Client: | Yo tengo un hijo. (I have one kid.) |

| Counselor: | ¿Uno? Yo tengo dos hijas pero son adultas. (One? I have two girls, but they’re grown-up.) |

|

| Psychological/ Interpersonal issues |

Counselor: | Tiene que resolver el sentido de vergüenza que has adquirido a través de esos años para que no impacte en ti. (You have to work through the feelings of shame that you have acquired through the years so that they don’t continue to impact you.) |

| Client: | ¿Sí? (Yeah?) | |

| Counselor: | Cuando tú tienes dudas, échate pa tras. Yo cogí una libreta de 60 centavos, y empezaba a escribir, hoy me siento enfogonada, no sé por qué, déjame averiguar qué es lo que me detiene con tanta rabia. Mañana escribía que me sentí con ganas de darle un puño a la persona que venga a tropezar. Cuando yo fui a revisarlo, yo dije, ok, ya yo sé, eso es un punto que tengo que bregar. (Whenever you have doubts, take a step back. I got myself a 60 cent notebook, and I started writing, today I feel angry, I don’t know why, let me try to find out what’s keeping me so angry. The next day I was writing that I felt like punching the first person that got in my way. When I went to revise it, I said, ok, now I know, this is something I need to address.) |

|

| Health issues | Client: | Me canso. (I get tired.) |

| Counselor: | Si no duermo bien en la noche, yo como un ratito, y me meto en mi carro, y tomo una dormidita de diez a quince minutos, y me refresco, ¿no? Porque yo no puedo dormirme muy temprano. (If I don’t sleep well at night, I eat for a little while, then I get in my car, and I take a little nap for ten to fifteen minutes, and I’m refreshed, no? Because I can’t fall asleep very early.) |

|

| Work-related issues | Client: | Voy al grupo por ahí mañana. (I’m going to that group over there tomorrow.) |

| Counselor: | O, yo trabajo los domingos por ahí. Pero no voy a estar este domingo. Voy a tomar una mini-vacación del trabajo. (Oh, I work there on Sundays. But I won’t be there this Sunday. I’m taking a mini-vacation from work.) |

|

| Opinions not related to client’s treatment |

Client: | Estoy batallando con las trockas. (I’m having a hard time working on the trucks.) |

| Counselor: | Sí se quiebran, se tiene que conseguir uno que sepa algo de la mecánica, o tú. Yo creo que la mayoría de los que manejan trockas ya saben algo. (Yeah they break-down, we need to find someone who knows something about mechanics, or you. I think the majority of people who drive trucks know something.) |

|

| Cooking/Food | Client: | Me acostumbré a tomar cerveza mientras cenando, me relaja. (I got used to drinking beer while having dinner, it relaxes me.) |

| Counselor: | Eso me hace recordar que mientras cenando, este señor me dijo que platicara de lo que yo quisiera, entonces le dije ah bueno, vamos a platicar entonces de chile relleno. (That reminds me, while eating, the man told me that we could chat about whatever I wanted, so I said to him, OK, let’s talk about “stuffed chile”.) |

|

| Job Market/Bargains | Counselor: | ¿Entonces trabajas afuera? (So you work outdoors?) |

| Client: | Sí, a veces afuera. (Yes, sometimes outdoors.) | |

| Counselor: | Ah, pues escucho que hay muchas personas ahorita preocupándose porque van a perder sus trabajos. (Ah, I hear there are many people now who are worried about losing their jobs.) |

|

| Client: | O, ¿por el frió verdad? (Oh, because of the cold right?) | |

| Counselor: | Sí. (Yes) | |

| Country of origin | Counselor: | ¿Qué es una de las cosas más difíciles que te ha pasado en tu vida? (What is one of the most difficult things that has ever happened to you in your life?) |

| Client: | Cuando tenía diez años, tuve problemas del estomago. (When I was ten, I had problems with my stomach.) |

|

| Counselor: | Yo como te dije soy Italiano, así en Italia, yo no sé, he pasado por varios problemas difíciles después de la guerra. (Like I told you, I am Italian, so in Italy, what do I know, I lived through many difficult problems after the war.) |

|

| Weather | Client: | Yo tengo familia en Montreal. (I have family in Montreal.) |

| Counselor: | O, ¡Canada es tan frío! (laughs) (Oh, Canada is so cold!) |

Note: These examples are not verbatim transcriptions. The information in them has been altered to broadly represent the informal discussion category and to protect the anonymity of the counselors and clients. Translations of the Spanish transcriptions were provided by three Spanish-fluent authors (WB, LA, and MP).

3.4. Did informal discussions differ between conditions?

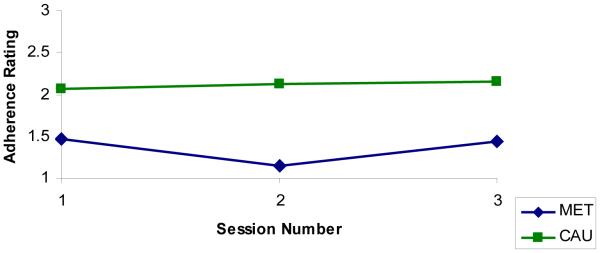

The MET counselors ‘chatted’ in significantly fewer sessions than CAU counselors (e.g., the proportion of sessions which received a rating of 2 or more, 20% vs. 45%, X2=22.82, p < .01). Counselors assigned to and implementing MET also talked informally significantly less often within sessions than counselors assigned to the CAU condition (mean scores of 1.55 vs. 2.12, F(1,323) = 30.89, p < .01). The occurrence of informal discussions was consistently higher in CAU than MET (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Informal discussion item mean adherence ratings per session for MET and CAU counselors.

Correlational analyses evaluating levels of informal discussion and counselors’ treatment integrity across conditions suggested that informal discussions were significantly negatively correlated with adherence and competence to fundamental (r = −.27, p < .01 for adherence and r = −.31, p < .01 for competence) and advanced MET strategies (r = −.13, p < .05 for adherence and r = −.35, p < .01 for competence). In addition, levels of informal discussions were significantly positively associated with adherence to MET inconsistent strategies (r = .32, p < .01) and negatively associated with the competence with which counselors implemented MET-inconsistent strategies (r = −.20, p < .01, n = 236). Level of informal discussion was negatively associated with the counselors’ overall therapeutic skillfulness (r = −.32, p < .01) and ability to maintain therapeutic structure within the session (r = −.38, p < .01).

3.5. What is the relationship between informal discussion and therapeutic alliance, client motivation, and treatment outcomes?

The frequency of informal discussion had a small but significant positive association with counselor-rated therapeutic alliance (r = .12, p < .05). However, when alliance was rated by clients, the association was not significant, and trended toward a negative relationship (r = −.10, p = .08). Informal discussion frequency was negatively associated with in-session increases in client motivation to reduce or stop substance use (r = −.24, p < .01).

Informal discussion had a significant negative association with the number of days clients were in treatment at the 4-week post-treatment point (r = −.14, p < .05) and over the duration of the 16-week study (r = −.22, p < .01). Informal discussion frequency was not significantly associated with percent days abstinent from primary drug at either assessment point (4-week post-treatment: r = −.09, p = .11; 12-week follow-up: r = −.09, p = .14).

3.6. What is the relationship between informal discussion and counselor ethnicity, counselor-client ethnic matching, and acculturation levels?

To examine the relationship of informal discussions with country/place of birth, we used a two-way ANOVA with the counselor birthplace, treatment condition, and their interaction as factors in the analysis. Counselors who were not born in Latin American countries (non Latin-born) had significantly higher levels of informal discussion than those that were born in Latin America (Latin-born) (2.07 vs. 1.51, F(1, 227) = 32.9, p < .01). A significant birthplace by treatment group interaction effect (F(1,227) = 31.7, p < .01) suggested that the birthplace difference in informal discussion frequency was primarily present in CAU rather than MET (3.42 vs. 1.18). This same pattern occurred for ethnic match. Client-counselor dyads that were not ethnically matched on birthplace talked informally more often than the matched dyads (2.02 vs. 1.48, F(1,226) = 10.4, p <.01). A matching/treatment condition interaction was present, showing that the significantly lower frequency of informal discussion for unmatched dyads (i.e., with non-Latin born counselors) occurred mostly in CAU (2.72 vs. 1.16, F(1,226) = 11.3, p < .01). No significant associations between informal discussion and acculturation levels (Hispanicism and Americanism) were found.

4. Discussion

This study replicates and extends Martino and colleagues’ (2009) findings regarding differences in levels of ‘chat’ between counselors delivering standard treatment and those trained to perform MET in a randomized clinical trial. As in the English trials, when MET was used with monolingual Spanish speaking Hispanic clients, data from the current study suggested 1) across treatment conditions, most counselors initiated ‘chat’ in at least one of their sessions; 2) counselors trained and assigned to implement MET talked informally significantly less often than counselors in the CAU condition; and 3) higher rates of informal discussion were associated with less adherence and competence to fundamental and advanced MET strategies, more frequent use of MET inconsistent strategies, lower ratings of counselor skillfulness, less ability to maintain session structure, and less in-session increases in clients’ motivation to stop or reduce substance use. Moreover, in the Spanish MET trial, more counselor-initiated informal discussion was associated with significantly poorer participant retention over the 16-week study period, though not related to the clients’ percent days of primary drug abstinence. Examination of ethnic factors influencing informal discussion frequency suggested that counselors not born in Latin American countries had higher levels of informal discussion in CAU than those born in Latin America.

This study, combined with our previous examinations of informal discussion (Martino et al., 2009), highlights how common counselor-initiated informal discussions (e.g., ‘chat’) may be in the delivery of substance abuse treatment in the United States. Eighty-three percent of Spanish-speaking counselors initiated informal discussions at least once in one or more of their sessions, and informal discussions occurred in a third of all sessions in the rated sample. These rates are comparable to those we found in the CTN English trial (Martino et al., 2009). As in the English trials, counselors informally discussed their opinions about matters unrelated to the clients’ treatment and personal information about their families or their psychological, interpersonal, or health problems. Unique to informal discussions in the Spanish MET trial were counselor-initiated conversations about their country of origin and comments about Hispanic food and cooking. These topics may have been raised by counselors to cultivate a culturally sensitive and familiar therapeutic environment for their Hispanic clients.

Data from both trials also suggested that formal training and supervision in MET, as well as participation in a clinical trial may reduce how often counselors talk informally with their clients. Counselors across conditions had similar demographic, educational, and professional characteristics/experiences, including the amount of pre-trial MET exposure and training (Carroll et al., in 2009). While baseline frequency of counselor informal discussion was not measured and the structure and attention provided through MET training/supervision was not controlled across conditions, MET counselors, in comparison to those delivering CAU, had significantly fewer sessions and less in-session frequency involving informal discussions. These findings give support to the notion that formal training in MET may increase the counselors’ focus on issues directly related to the clients’ treatment (consistent with MET’s client-centered stance), hence, reducing the amount of informal discussion. Alternatively, rigorous training in MET or any other treatment might reduce the tendency of counselors to stray from issues central to a client’s treatment by providing counselors with a coherent therapeutic framework that guides what they say and do in sessions (Martino et al., 2009). Future research is needed to determine if training in empirically supported treatments other than MET may have similar effects.

Exploration of ethnic factors associated with informal discussion yielded some interesting findings. Non-Latin born counselors initiated informal discussion more often than Latin-born counselors, unless they received formal training and supervision in MET. What these findings suggest is unclear and may relate to differential salience of certain cultural values early in the treatment process. For example, Hispanic cultural values that promote formality and deference in relationships (e.g., formalismo, respeto), rather than those geared toward establishing more personal relationships (e.g., confianza and personalismo), may be more important among Hispanics during initial professional interactions and suppress informal discussion. Martinez (1986) and Paniagua (2005) echo this idea, stating that counselors should adhere to formalismo in the first session of therapy, avoiding any discussion that is unrelated to the reason for which the client is seeking treatment, while emphasizing personalismo later on where plática or “chat” may have relevance. Non-Latin born counselors are likely less influenced by this value system and potentially prone to talk more informally early in treatment unless trained to do otherwise. It is also possible that non-Latin born counselors disclosed more than Latin-born counselors in order to strengthen rapport with their Hispanic clients who differed ethnically from them. These possibilities are tempered by the absence of significant associations between informal discussion and the acculturation factors of Americanism and Hispanicism. Furthermore, this study did not directly examine or measure cultural values endorsed by the clients or directly assess their relationship with informal discussion frequency. Future research should be focused on the systematic evaluation of the influence of cultural values on the treatment process with Hispanic clients.

The study has several limitations. First, the study only examined informal discussion in early treatment sessions. Second, only CTN program-affiliated counselors participated in this study, and they may differ from counselors who are not involved in CTN protocols or programs (Ducharme & Roman, 2009). Third, the participating sites may have been unusual in that they had a minimum of four bilingual therapists, a fairly large number given the shortage of bilingual Spanish-speaking staff in the US workforce (Atdjian & Vega, 2005; Diaz, Prigerson, Desai, & Rosenheck, 2001). Thus, it is not clear how this study’s findings generalize to other settings or counselors. Fourth, the number of counselors in this study is small, particularly within the analyses involving ethnicity because counselors at one site did not provide cultural data. Finally, the correlational nature of the data prohibits conclusions about the direction of relationships reported in this study. For example, counselor-initiated informal discussion may be in reaction to client statements that suggest lower motivation to change (e.g., to reduce tension in the conversation) rather than causing clients to become less motivated.

Nonetheless, together with the findings from the English version of the study (Martino et al., 2009), these findings suggest that a meaningful proportion of counselors initiate discourse during sessions that is unrelated to the issues for which their clients sought treatment, and that such discourse may be experienced negatively by clients. As in the CTN English MET trials, training and supervision of counselors in MET for use with Spanish-speaking clients may help reduce the occurrence of informal discussions and keep conversations focused on those topics most pertinent to retaining clients in treatment and enhancing their motivation to change their substance use.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Drug Abuse supported this study in the form of individual grants to the medical schools of Yale University (U10 DA13038 awarded to Kathleen Carroll) and University of Miami (U10 DA13720 awarded to José Szapocznik). The authors are grateful to the individuals who helped develop the rating manual (Joanne Corvino, MSW, and Jon Morgenstern, PhD); the individuals responsible for the development, training, and coordination of the independent tape rating system (Joanne Corvino, Luis Añez, Manuel Paris); the MI expert site supervisors (Luis Añez, Christiane Farentinos, Patricia Juarez, Manuel Paris); program executive directors (Rhonda Bohs, Richard Drandoff, Janet Lerner, Carol Luna-Anderson, John Wilde); the study coordinators (Lourdes Suarez-Morales, Ani Bisono Ivette Cuzmar, Catherine Dempsey, Jennifer Lima, Lynn Kunkel, Marilyn Macdonald, Jennifer Smith, Jennifer VanLare); the independent tape raters (Tamara Armstrong, Luis Bedregal, Julianne Cossio, Hector Lizcano, Mary Jane Kerr, Ruth Martinez, Marylin Quintero, Darlene Riviera, Michelle Silva, Ivelisse Suarez), CIDI trainers (Dr. Maritza Rubio-Stipec), protocol coordinators (Julie Matthews and Lourdes Suarez-Morales) and to the counselors and clients who participated in the Spanish MET protocol. The rating scales described in the study are available from Dr. Martino.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alegria M, Page JB, Hansen H, Cauce AM, Robles R, Blanco C, et al. Improving drug treatment services for Hispanics: Research gaps and scientific opportunities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Arevalo S, Gonzalez G, Szapocznik J, Iguchi MY. Needs and scientific opportunities for research on substance abuse treatment among Hispanic adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84(Suppl 1):S64–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Añez LM, Paris M, Bedregal LE, Davidson L, Grilo CM. Application of cultural constructs in the care of first generation Latino clients in a community mental health setting. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:221–30. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Añez LM, Silva MA, Paris M, Bedregal LE. Engaging Latinos through the integration of cultural values and motivational interviewing principles. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H, Westra H, Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Atdjian S, Vega WA. Disparities in mental health treatment in U.S. racial and ethnic minority groups: Implications for psychiatrists. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:1600–1602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Christoph P, et al. Site matters: Motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment related epidemiological findings among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Farentinos C, Ball SA, Crits-Christoph P, Libby B, Morgenstern J, et al. MET meets the real world: Design issues and clinical strategies in the Clinical Trials Network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00255-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter T, Añez L, et al. A multisite randomized effectiveness trial of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance users. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:993–999. doi: 10.1037/a0016489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecero JJ, Fenton LR, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. Focus on therapeutic alliance: The psychometric properties of six measures across three treatments. Psychotherapy. 2001;38:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cherbosque J. Differential effects of counselor self-disclosure statements on perception of the counselor and willingness to disclose: a cross-cultural study. Psychotherapy. 1987;24:434–437. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E, Prigerson H, Desai R, Rosenheck R. Perceived needs and service use of Spanish speaking monolingual patients followed at a Hispanic clinic. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37:335–346. doi: 10.1023/a:1017552608517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Opioid treatment programs in the Clinical Trials Network: Representativeness and buprenorphine adoption. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloria AM, Peregoy JJ. Counseling Latino and other substance users/abusers: Cultural considerations of counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(96)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR, Burckell LA, Eubanks-Carter C. Therapist self-disclosure in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session. 2003;59:529–539. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GR, Leshner AI, Tai B. Putting drug abuse research to use in real-life settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:69–70. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Knox S. Self-disclosure. Psychotherapy. 2001;38:413–417. [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Diaz-Martinez AM. Considerations for culturally competent cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression with Hispanic patients. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:84–97. [Google Scholar]

- La Framboise TD, Coleman H, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L, Barber J, Siqueland L, Johnson S, Najavits L, Frank A, Daley D. The revised helping alliance questionnaire (HAq-II) Journal of Psychotherapy Practice & Research. 1996;5:260–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke B. Meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty Five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Mallow AJ. Reconciling psychoanalytic psychotherapy and alcoholics anonymous philosophy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:493–498. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TC, Carroll KM. Community program therapist adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TC, Carroll KM. Informal discussions in substance abuse treatment sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SH, Becklman HB, Morse DS, Silberman J, Seaburn DB, Epstein RM. Physician self-disclosure in primary care visits. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1321–1326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. Gilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for counselors treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Vol. 2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1992. Project MATCH Monograph Series. [Google Scholar]

- Multon KD, Ellis-Kalton CA, Heppner MJ, Gysberg NC. The relationship between counselor verbal response modes and the working alliance in career counseling. The Career Development Quarterly. 2003;51:259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua FA. Guidelines for the assessment and treatment of Hispanic clients. In: Paniagua FA, editor. Assessing and treating culturally diverse clients: A practical guide. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks (CA): 2005. pp. 48–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care. Guildford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz P. Assessing, diagnosing and treating culturally diverse individuals: a Hispanic perspective. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1995;66:329–341. doi: 10.1007/BF02238753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Carroll KM, Añez L, Paris M, Ball S, Nich C, et al. Evaluating motivational enhancement therapy adherence and competence among Spanish-speaking therapists. Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simi NL, Mahalik JR. Comparison of feminist versus psychoanalytic/dynamic and other therapists on self-disclosure. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumptions: Psychosocial and biological methods. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Morales L, Matthews J, Martino S, Ball S, Rosa C, Farentinos C, et al. Issues in designing and implementing a Spanish-language multi-site clinical trial. The American Journal on Addictions. 2007;12:206–215. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Morales L, Martino S, Bedregal L, McCabe BE, Cuzmar I, Paris M, et al. Do therapist cultural characteristics influence the outcome of substance abuse treatment for Spanish-speaking adults? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0016113. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Fujino D, Hu L, Takeuchi D, Zane N. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Arredondo P, McDavis RJ. Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1992;20:64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Fernandez T. Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1980;4:353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor C, Tetlock P. Biculturalism: A model of the effects of second-culture exposure on acculturation and integrative complexity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Torres JB. Communication patterns and direct social work practice with Latinos in the U.S. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2000;3:23–42. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Census bureau estimates nearly half of children under age 5 are minorities. 2009 Retrieved September 16, 2009 from http://www.census.gov/PressRelease/www/releases/archives/population/013733.html.

- Volkow ND. Hispanic drug abuse research: Challenges and opportunities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner LA, Avelardo V, Vega WA, de la Rosa M, Turner RJ, Canino G. Hispanic drug abuse in an evolving cultural context: An agenda for research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S8–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaohui G, Suarez-Morales L, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the bicultural involvement questionnaire–Short version. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:22–31. doi: 10.1037/a0014495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Mak W. Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2003. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]