Abstract

Development of synovial joints involves generation of cartilaginous anlagen, formation of interzones between cartilage anlagen, and cavitation of interzones to produce fluid filled cavities. Interzone development is not fully understood, but interzones are thought to develop from skeletogenic cells that are inhibited from further chondrogenic development by a cascade of gene expression including Wnt and Bmp family members. We examined the development of the rarely studied avian costal joint to better understand mechanisms of joint development. The costal joint is found within ribs, is morphologically similar to the metatarsophalangeal joint, and undergoes cavitation in a similar manner. In contrast to other interzones, Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, Barx1, and Bapx1 are absent from the costal joint interzone, consistent with the absence of active β-catenin and phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8. However Autotaxin and Noggin are expressed. The molecular profile of the costal joint suggests there are alternative mechanisms of interzone development.

Keywords: Skeleton, Joint, Synovial joint, Chick, Development, Wnt14/9a, Wnt14, Wnt9a, Gdf5, Autotaxin, Costal Joint, Rib, Interzone, Cartilage

Introduction

The joints between vertebrate skeletal elements are morphologically variable, and their distinct morphologies dictate their physical properties. Synarthroses are joints that allow minimal movement and consist of either cartilaginous or fibrous connections between skeletal elements. Amphiarthroses are joints with cartilaginous discs that separate the elements, and have a continuous periosteum connecting the elements, such as between adjacent vertebral centra. Synovial joints are the most flexible joints and are found in the limbs and jaws of most vertebrates. Also called diarthroses, synovial joints consist of a fluid filled cavity with a synovial lining, and they often have a fibrous capsule encasing them.

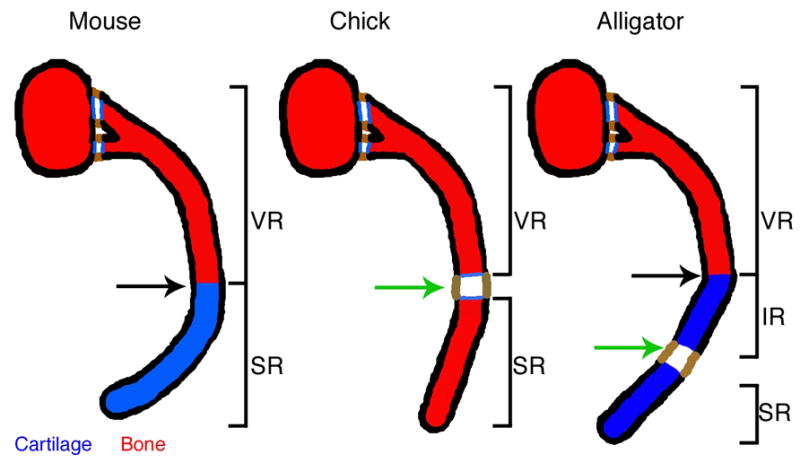

The ribs of tetrapods vary in having either one or two joints within them (Parker, 1867; Hyman, 1972). We refer to these joints as “costal joints”. When a single joint is present, it unites the vertebral and sternal elements of the rib (Figure 1). Different taxa possess different costal joint types that are correlated with their ventilation strategies (Gans, 1970; Claessens, 2009). The single costal joint is a synarthrose in most mammals, but is a synovial joint in birds (Parker, 1867; Claessens 2008).

Figure 1.

Although joint development in general has received considerable attention, no recent studies have been directed toward costal joint development. Synovial joint development seems largely conserved between anatomical locations and between species, although most studies have been conducted on joints in the limb. Synovial joint development can be roughly divided into three steps; condensation of skeletogenic progenitors to form the cartilaginous anlagen, formation of a morphologically distinct interzone at the future joint site, and cavitation of the interzone to form a fluid filled cavity uniting adjacent cartilages.

Prechondrogenic condensations are the first morphological indication of cartilage development (Fell, 1925; recently reviewed in Weatherbee and Niswander, 2007). All prechondrogenic condensations express the transcription factor Sox9, which is both necessary and sufficient for condensation and cartilage maturation (Wright et al., 1995; Healy et al., 1999; Bi et al., 1999; Akiyama et al., 2002). Prechondrogenic condensations also express the structural proteins Tenascin and Collagen IIA (Sandell et al., 1991; Pacifici et al., 1993). Tenascin is an extracellular matrix component that is produced by prechondrogenic condensations, and is eventually restricted to the perichondrium upon maturation into cartilage (Pacifici et al., 1993; Koyama et al., 1995; Gluhak et al., 1996). As prechondrogenic condensations differentiate into cartilage they also increase synthesis of Collagen II, which is the defining extracellular matrix component of cartilage (Linsenmayer et al., 1973, Pitsillides and Ashhurst, 2008). Specifically, the IIB isoform is expressed (Sandell et al., 1991).

The joint forming region is histologically recognizable as three a layered structure called the interzone (Mitrovic, 1978). Interzones form within prechondrogenic condensations, either during or after differentiation into cartilage (Mitrovic, 1978; Shubin and Alberch, 1986; Archer et al., 2007; Pitsillides and Ashhurst, 2008). The interzones of developing jaw, limb, and fin joints all express a similar complement of signaling molecules and transcription factors, which suggests that a similar molecular mechanism is employed during the development of many joints (Crotwell and Mabee, 2007). The first non-structural molecule identified in interzones was Gdf5 (Storm and Kingsley, 1996). Other genes have since been identified, including Wnt14/9a (Hartmann and Tabin, 2001), Chordin (Archer et al., 2003), Noggin (Brunet et al., 1998), Autotaxin (Hartmann and Tabin, 2001), Bapx1 (Wilson and Tucker, 2004), and Barx1 (Barlow et al., 1999), among others.

Based on the conformity of gene expression and results of experimental manipulations, a mechanistic model of interzone development has begun to emerge. Gdf5 and related signaling molecules are expressed in the interzone, where they induce anti-Bmp molecules such as Noggin and Chordin that inhibit chondrogenesis in the interzone (Brunet et al., 1998; Merino et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2002). Wnt14/9a and other Wnts are also expressed in the interzone, where they activate β-catenin that also inhibits chondrogenesis (Hartmann and Tabin, 2001; Später et al., 2006b). Data from mouse knockouts for many interzone associated signaling molecules surprisingly display phenotypes in only a subset of joints, despite the extreme conservation of gene expression between joints (Gdf5, Storm and Kingsley, 1996; Chordin, Bachiller et al., 2003; Wnt14/9a, Später et al., 2006a,b). This suggests that some amount of functional redundancy of signaling exists for these genes. Unlike the inconsistent effects of the former signaling molecule knockouts, genetic ablation of either β-catenin or Noggin causes widespread joint fusions (Brunett et al., 1998, Guo et al., 2004; Hill et al., 2005), demonstrating that cartilage inhibition is required for joint development.

The last stage of synovial joint development is the formation of a fluid filled cavity lined by a synovial membrane that is derived from interzone cells (Mitrovic, 1977; Dowthwaite et al., 2003; Rountree et al., 2004). Cavitation requires embryonic movement (Murray and Drachman 1969; Hosseini and Hogg, 1991; Osborne et al., 2002), synthesis of the extracellular matrix component Hyaluronan (Craig et al., 1990; Edwards et al., 1994), and binding of Hyaluronan to its receptors, such as Cd44 (Dowthwaite et al., 1998). Hyaluronan synthesis within the interzone is thought to physically separate interzone cells, cavitating the structure (Craig et al., 1990; Edwards et al., 1994, reviewed in Pacifici et al., 2005). Hyaluronan synthesis can be induced by receptor binding and embryonic movement (Dowthwaite et al., 2003). Both Cd44 and Hyaluronan are expressed in the interzone in the stages prior to and after cavitation, placing them in the correct time and place to separate interzone cells (Craig et al., 1990; Dowthwaite et al., 2003). Cavitation results in a morphologically mature joint that is often encased in a fibrous joint capsule that expresses Collagen I (Nalin et al., 1995). Cavitated joints also posses a synovial lining that maintains Cd44 expression (Edwards et al., 1994).

In this paper we describe development of the costal joint in chick. We compare our findings in the costal joint to the metatarsophalangeal joint, which serves as a control for typical joint development. We confirm that the costal joint is synovial; the late embryonic morphology of the costal joint is similar to the metatarsophalangeal joint. Based on analysis of histology and protein expression, we find that a similar mechanism of cavitation is employed in both the costal and metatarsophalangeal joints. Interzones develop from condensed cells that are Sox9 positive in both joints. Collagen II mRNA is only briefly expressed in the costal joint prior to interzone formation, and protein was not detected in either joint. Expression of signaling genes in the costal joint is conspicuously different from expression in both the chick metatarsophalangeal joint, as well as other joints described in the literature. Though Noggin and Autotaxin expression in the costal joint is consistent with limb joints, Gdf5, Wnt14/9a, Chordin, Barx1, and Bapx1 are all absent from the costal joint interzone. We examined down stream signaling molecules to test the hypothesis that the Gdf5 and Wnt14/9a signaling pathways are activated by functionally redundant signaling molecules. Gdf5 phosphorylates Smads 1/5/8 (Chen et al., 2006), and Wnt14/9a activates β-catenin in joint development (Später et al., 2006b), both of which show no evidence of activation in the costal joint. These findings suggest that alternative mechanisms to those proposed to date can mediate synovial joint development.

Results

The chick costal joint is synovial

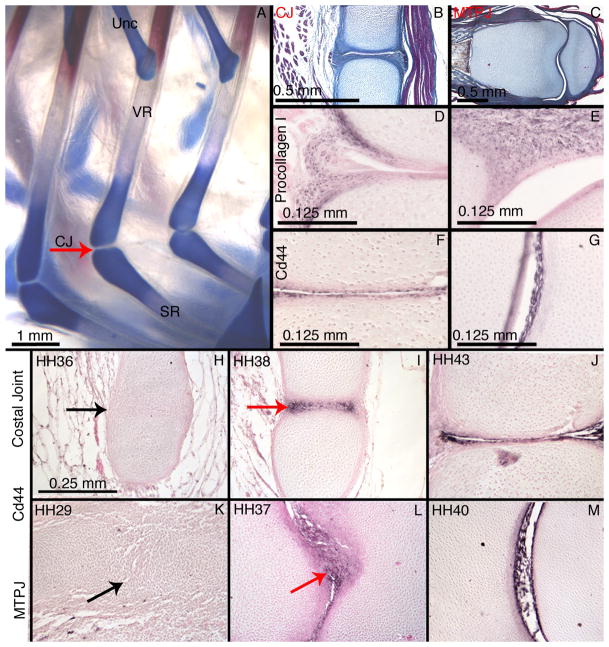

We confirmed that the chick costal joint is a synovial joint by comparing histological sections of mature costal joints from HH43 chick embryos to HH40-43 metatarsophalangeal joints. Trichrome staining at these stages clearly demonstrated a joint cavity in each joint (Figure 2B–C). We confirmed the presence of a fibrous joint capsule by immunohistochemistry for Procollagen I. Procollagen I is found in the outer lining of both the costal joint and metatarsophalangeal joint (Figure 2D–E). Finally, we confirmed the presence of a synovial lining by immunohistochemistry for Cd44. The inner surfaces of both the costal joint and the metatarsophalangeal joint are Cd44 positive, as expected (Figure 2F–G). These data allow us to characterize the costal joint as a synovial joint with gross morphological similarity to the metatarsophalangeal joint.

Figure 2.

We further examined Cd44 expression to determine if a similar cavitation mechanism is employed in the costal joint and the metatarsophalangeal joint. In both joints, Cd44 is absent from newly formed interzones (Figure 2H,K), but is found just prior to, and after cavitation (Figure 2I-J,L-M). These data show that both joints express Cd44 protein in the same time frame relative to cavitation.

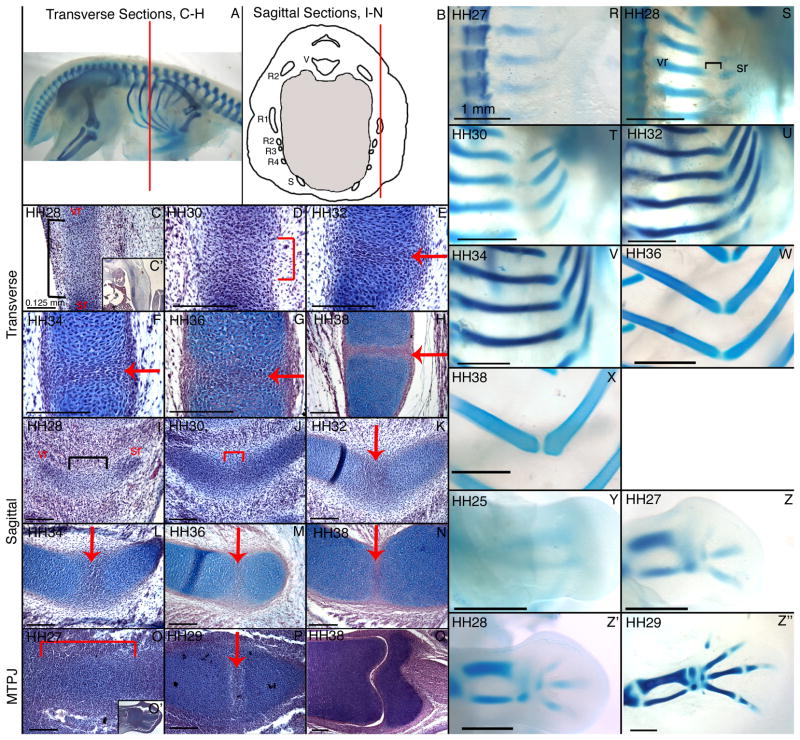

The costal joint develops between two prechondrogenic condensations

To investigate the morphological development of the costal joint, we prepared developmental series of alcian blue stained whole mount specimens and histological sections stained with alcian blue, hematoxylin, and eosin (Figure 3). The vertebral rib and sternal rib condensations form as distinct condensations. The vertebral rib is visible first, and the sternal rib condensation forms lateral/ventral to it. Mesenchyme extends between the vertebral and sternal rib condensations at HH28 (Figure 3C,I). We refer to this as intermediate mesenchyme, based on its slight level of condensation and its location. As development proceeds, the intermediate mesenchyme in the presumptive costal joint further condenses into precartilage that stains lightly with alcian blue, uniting the vertebral and sternal rib elements around HH30-32 (Figure 3D,J). We never observe continuous cartilage (well spaced nuclei and intense alcian blue staining) across the costal joint in either whole mount or histological sections. This is particularly obvious in whole mount cleared and stained specimens.

Figure 3.

By HH32, a region of flattened, closely associated cells that form an interzone is present in the presumptive costal joint (Figure 3E,K). This layer becomes progressively more distinct in HH34 (Figure 3F,L), HH36 (Figure 3G,M) and HH38 costal joint sections (Figure 3H,N).

The metatarsophalangeal joint interzone forms rapidly as limb differentiation proceeds proximally to distally (Figure 3O–Q, Y–Z”). A readily identifiable interzone is present in HH29 metatarsophalangeal joints (Figure 3P,Z”), thus we use this stage for further comparisons. In contrast to the costal joint, intermediate mesenchyme is not observed between the metatarsus and first phalange prior to interzone formation (Figure 3O). Rather, these elements mature from a single, continuous condensation.

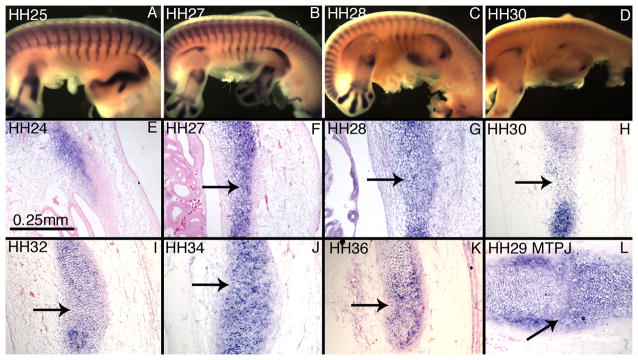

Sox9 expression is continuous across the presumptive costal joint

To characterize the nature of the intermediate mesenchyme between the vertebral and sternal rib condensations in more detail, we examined Sox9 expression. Sox9 is found in the rib primordia as early as HH25 (Figure 4A,E). Expression is continuous across the presumptive costal joint, which is distinguished by an anterior bend in the expression domain (Figure 4A–C). As development continues, Sox9 expression extends toward the sternum, but remains continuous across the presumptive costal joint (Figure 4B,C). At HH30, Sox9 is no longer detectable in the ribs of whole mount specimens (Figure 4D), but can be detected by in situ hybridization on paraffin sections (Figure 4H). Sectional in situ hybridization confirms that Sox9 expression remains continuous across the costal joint through HH36 (Figure 4E–K). Expression is absent from the interzone by HH38 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Sox9 expression is continuous in the digit rays at HH27 (data not shown), prior to metatarsophalangeal joint interzone formation. Sox9 expression remains continuous across the metatarsophalangeal joint interzone at HH29 (Figure 4L).

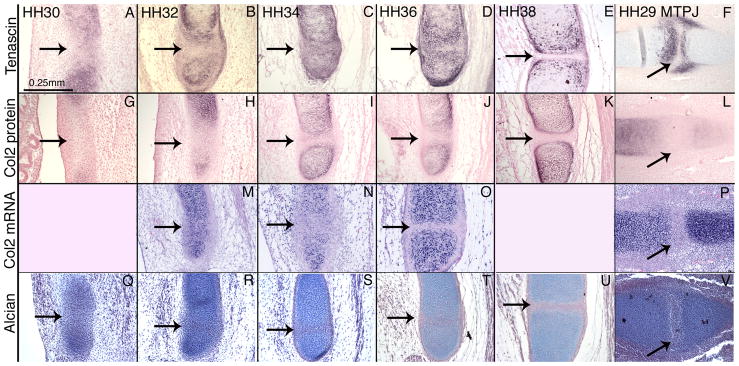

The costal joint interzone develops from skeletogenic cells after they condense

To determine the degree of cartilage differentiation in presumptive costal joint cells when they form the costal joint interzone, we examined Tenascin protein and Collagen II protein and mRNA. At HH30, Tenascin protein expression is found in the vertebral rib and sternal rib and is weakly expressed in the presumptive interzone (Figure 5A). At HH32, Tenascin is expressed in the periphery of the interzone, but it is absent from the central portion (Figure 5B). Tenascin is expressed throughout the costal joint at HH34. At HH36, Tenascin is found in the articular cartilage, joint capsule, and perichondrium, and it appears reduced in the interzone (Figure 5D). Tenascin is absent from the HH38 interzone (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

We examined Collagen II expression with an antibody that does not discriminate between isoforms (Linsenmayer and Hendrx, 1980, Oganesian et al., 1997). Collagen II protein is absent from the costal joint at all stages examined (Figure 5G–K). Collagen II expression in the vertebral and sternal rib is initially separated by a relatively long band of intermediate mesenchyme (Figure 5G). However, the distance between expression in the vertebral and sternal ribs appears shorter in older stages. By HH34, Collagen II expression is adjacent to the costal joint interzone (Figure 5I). In contrast, we found Collagen II mRNA expression across the presumptive costal joint at HH32 (Figure 5M), but no expression in the costal joint at HH34 (Figure 5N) or HH36 (Figure 5O).

At HH29, the metatarsophalangeal joint expresses Tenascin in the articular cartilage and in the joint capsule, but not in the interzone (Figure 5F). Collagen II protein and mRNA are also absent from the metatarsophalangeal joint interzone at this time (Figure 5L,P). These data suggest that the costal joint is most equivalent to the HH29 metatarsophalangeal joint at HH36.

Costal joint gene expression

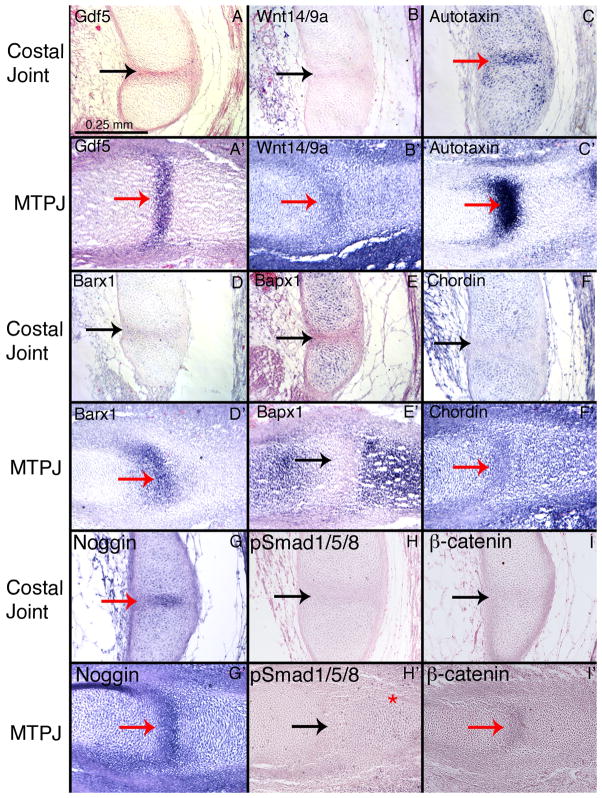

We hypothesized that the costal joint interzone would have similar gene expression to the metatarsophalangeal joint interzone, because interzone gene expression is largely conserved between anatomical locations and between species. We examined the interzone markers Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Autotaxin, Chordin, Barx1, and Bapx1 by in situ hybridization on paraffin sections through the costal joint at stages HH34, HH36 (Figure 6), HH37, and HH38, and compared them to HH29 metarsophalangeal joints mounted on the same slides. As expected, Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Barx1, Noggin, Chordin, and Autotaxin are all expressed in HH29 metatarsophalangeal joints, while Bapx1 is expressed in the limb cartilage (Figure 6A′–G′). Notably, Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, and Barx1 are all absent from the costal joint interzone and cartilage (Figure 6A–B, D–F). The only signaling genes we examined that are expressed in the costal joint interzone are Autotaxin and Noggin (Figure 6C,G). Bapx1 is expressed in the rib cartilage, similar to its expression in limbs (Figure 6E,E′). Chordin is also weakly expressed in the rib cartilage, and is absent from the interzone.

Figure 6.

We tested the hypothesis that functionally redundant signaling molecules were performing the functions normally fulfilled by Gdf5 and Wnt14 by examining their down stream signaling transduction molecules. We followed the logic that if a signaling molecule does perform the function of either Gdf5 or Wnt14/9a, it should activate their respective signaling pathways. We examined phosphorylated Smads 1/5/8, a component of Gdf5 signal transduction, via immunohistochemistry on HH36 costal joints and HH30 metatarsophalangeal joints. We found positive staining in the phalangeal cartilage adjacent to the metatarsophalangeal joint, but found no positive staining in costal joints (Figure 6H-H′). We also examined the presence of activated β-catenin by immunohistochemistry to check for Wnt signal transduction. Again, we found staining in the HH29 metatarsophalangeal joint, but no positive staining in the costal joint at HH36 (Figure 6I-I′).

Discussion

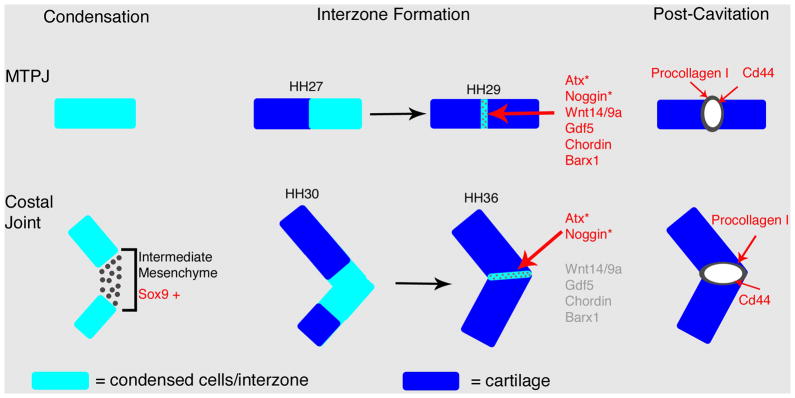

Synovial joints allow the greatest mobility for articulated skeletal elements. The development of these joints has garnered much attention from developmental biologists. The bulk of studies have been conducted on limb joints, which have generated models of joint formation. Joint development typically proceeds through condensation of skeletal progenitors, formation of an interzone, and cavitation. Of these processes, the mechanisms underlying interzone formation are the most unclear. It has been generally assumed that interzone development is identical in all anatomical locations (Pitsillides and Ashhurst, 2008). Our data demonstrate that the chick costal joint is synovial and that some aspects of development conform with the metatarsophalangeal joint. However, though the late embryonic morphology of the costal joint is similar to the metatarsophalangeal joint, the costal joint interzone develops more slowly, and has a considerably different molecular profile (summarized in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Interzone formation in the costal joint

The formation of the costal joint interzone differs from typical limb joint formation in temporal and molecular aspects despite several conserved characteristics. The costal joint differs from the metatarsophalangeal joint early in development by the presence of intermediate mesenchyme between condensations at the presumptive joint site (Figure 3). The vertebral and sternal rib cartilages appear to converge toward the site of the joint, rather than becoming distinct from one another at the site of joint formation as classically described in the limb (Shubin and Alberch, 1986; Archer, 2007). The development of the costal joint also progresses more slowly than the metatarsophalangeal joint (Figure 3). The vertebral and sternal rib condensations are present by HH28, at least 48 hours before an interzone can be identified (HH32). The interzone becomes progressively more distinct over stages HH32-38, spanning several days, and only acquires similar Sox9, Collagen II, and Tenascin expression by HH36, 3–4 days after the initial appearance of the distinct elements (Figure 5). In contrast, condensation and interzone formation in the metatarsophalangeal joint occur at HH27 and HH29 respectively, a period of less than 24 hours.

Interzone gene expression

The patterning genes Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, Noggin, Autotaxin, and either Barx1 or Bapx1 have been found in all previously described interzones. We find these genes in the typical time and place during metatarsophalangeal joint formation, but Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, and Barx1 are absent from similar stages in costal joint formation (Figure 6). When each of these genes has been knocked out genetically in mice or knocked down with morpholinos in zebrafish, the effects are limited to a subset of joints (Storm and Kingsley, 1996; Tribioli and Lufkin, 1999; Bachiller et al, 2003; Miller et al., 2003; Später et al., 2006a,b; Sperber and Dawid, 2008). These data suggest that these genes are not essential for the unaffected joints. These findings have been interpreted to indicate the existence of some functional redundancy of signaling from other gene family members (Archer et al., 2007). If functional redundancy did occur, the individual absence of each gene from the costal joint would not be surprising. However, we tested the hypothesis of functional redundancy by examining phosphorylated Smads 1/5/8 and activated β-catenin. If unscreened signaling molecules do fulfill the roles of Gdf5 or Wnt14/9a in the costal joint, we would expect to see activation of their signal transducers. These downstream transduction molecules are not active in the costal joint, indicating that the functions of Gdf5 and Wnt14/9a are not fulfilled by redundant signaling molecules.

Common factors in interzone formation

We have emphasized the differences between costal joint development and other joints, however assessing the similarities between the costal joint and the metatarsophalangeal joint may also provide insight into the mechanisms of joint development. Interzones in the costal joint and metatarsophalangeal joint both develop from condensed cells that express Sox9, the cartilages adjacent to both joints express Bapx1, and both interzones express Autotaxin and Noggin. Noggin is required for interzone formation or maintenance in mice at all locations (Brunet et al., 1998). Its expression in the costal joint is consistent with the interpretation that Noggin is required for the development of all joints. The expression of Autotaxin in a wide range of joints, including the costal joint, suggests that it may also be part of a functional mechanism required for joint formation. Unfortunately, Autotaxin deficient mice die around embryonic day 9.5 from vascular deformities (Ferry et al., 2007), therefore an analysis of Autotaxins role in joint development has not been performed.

The final stage of joint formation considered here is cavitation. Cd44 is likely involved in this process and its expression follows the same time frame in the costal joint and the metatarsophalangeal joint (Figure 2). Our data combined with the requirement of movement for successful cavitation in the costal joint (Hosseini and Hogg, 1991) suggests that the cavitation mechanisms employed by other joints are also used in the costal joint.

Summary and Conclusion

To further understand the mechanisms of joint development, we examined the development of the chick costal joint. We found that the interzone develops slowly relative to the adjacent cartilages in comparison to the metatarsophalangeal joint. We also found that in contrast to all other interzones yet described, the costal joint interzone does not express Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, Barx1, or Bapx1. The costal joint interzone does express Autotaxin and Noggin, and the cartilage of the rib expresses Bapx1, an expression profile that is shared with the developing digits. We therefore conclude that Noggin and Autotaxin are likely required for interzone development in all joints. The chick costal joint is morphologically similar to other synovial joints, and appears to use the same cavitation mechanism as other joints, despite the differences observed in interzone development and gene expression.

Our data indicate that an alternative or less elaborate genetic network is competent to initiate and complete synovial joint formation in some contexts. The absence of expression of Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, and other genes from the costal joint also demonstrate that these genes are genetically independent from the expression of Autotaxin and Noggin. The absence of expression of many genes necessary in other joints from the costal joint requires an explanation. We propose that the relative timing of differentiation events may necessitate the involvement of additional patterning genes to properly orchestrate joint formation in the context of the limb. Accordingly, the absence of Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, and Barx1 from the costal joint may be related to the relatively slow differentiation of the interzone and adjacent cartilage in the costal joint compared to the metatarsophalangeal joint. Under this hypothesis, Gdf5 and other interzone Bmps could be thought of as accelerating skeletal development in the limb, which further necessitates the use of chondrogenic inhibitors (i.e. Wnts) to establish and/or maintain the interzone.

Experimental Procedures

Embryos

Fertile chick eggs were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (North Franklin, CT). Eggs were incubated at 37°C and staged according to Hamburger and Hamilton (HH), 1951. For Procollagen I and Collagen II immunohistochemisty, embryos were fixed in Dent’s fixative (80% methanol, 20% DMSO). Embryos were fixed with 4% PFA in DEPC PBS for all other uses. Embryos were stored at −20C in 100% methanol.

All analyses were performed using costal joints from either the 2nd or 3rd complete rib. HH29 metatarsophalangeal joints were used for most comparisons, because this stage provides a newly formed interzone that is easily recognizable (Craig and Archer, 1987).

Clearing and staining

Cartilage and bone were visualized with alcian blue and alizarin red following Shearman, (2005) except that embryos were bleached with 5% Hydrogen Peroxide prior to staining. Specimens younger than HH36 were not trypsinized. Alizarin red steps were omitted for most specimens, except were shown.

Histology

Embryos were cleared with citrisolv, embedded with paraplast paraffin wax, and sectioned using a HM 340 E microtome. All histological solutions were prepared following Humason, 1972. Trichrome staining was performed on paraffin sections 20 micrometers thick following the Pantin method (Humason, 1972). Sections were deparaffinized with citrisolv, rehydrated and incubated in magnesium chloride in 5% acetic acid as a mordant. Excess magnesium chloride was removed with Lugols Iodine solution. Sections were incubated in Mallory I, transferred to phosphomolybdic acid, rinsed in water, incubated in Mallory II, rinsed in water, then quickly dehydrated by rinsing in 95% ethanol, and two rinses in 100% ethanol before being transferred to citrisolv and cover slipped.

Histology with alcian blue, hematoxylin, and eosin was performed on 12-micrometer paraffin sections. Sections were deparaffinized in citrisolv, rehydrated through an ethanol series into water, stained in Harris Hematoxylin, rinsed in running water, incubated in Scotts solution, rinsed in running water, incubated in Eosin, transferred to 70%, 2×95% ethanol, incubated in alcian blue (1mg/ml), transferred to 95%, then 100% ethanol. Sections were rinsed again in 100% ethanol, transferred to citrisolv and cover slipped.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections 8–12 micrometers thick. Sections were deparaffinized in citrisolv, and rehydrated through an ethanol series to PBS containing 0.1–1% tween-20 (PBST). Antigen unmasking was performed by boiling in 0.01M citric acid, pH6, (Tenascin, Phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8) or 0.01M tris buffer (active β-catenin), pH 9.5 for 10 minutes. Sections were blocked in 10% horse serum in PBST (Tenascin, Collagen II, Procollagen I, Cd44) or 5% normal goat serum (Phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8, Activate β-catenin) for 1 hour, and incubated in primary antibody in block over night at 4C. Slides were rinsed 3 times in PBST, incubated in 6% hydrogen peroxide in PBST for 10 minutes, and rinsed 3 times in PBST.

The vectastain elite standard ABC kit (Vector labs) was used for detection and amplification following the manufacturers instructions. 0.5% NiCl was added to the DAB solution to produce purple coloration. After detection and reaction, sections were counterstained with eosin and cover slipped. Tenascin was detected with the M1-B4 antibody at 1:200, Collagen II was detected with the II-II6B3 antibody at 1:30, Procollagen I was detected with the SP1.D8 antibody at 1:100, and Cd44 was detected with the 1D10 antibody at 1:200. Tenascin, Collagen II, Procollagen I, and Cd44 antibodies were purchased from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. The phosphorylated Smad 1/5/8 antibody was used at 1:300, and purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (#9511). The active β-catenin antibody was used at 1:100, and purchased from Millipore (Clone 8E7, # 05-665).

In situ hybridization

Whole mount in situ hybridization of Sox9 followed Riddle et al., 1993, without glycine washes. In situ hybridization on paraffin sections followed Moorman et al., 2001. Hybridization was performed with rubber-lined plastic cover slips to avoid desiccation, and solutions followed Riddle et al., 1993. Sections were treated with Protinase-K in PBST (10 micrograms per ml) at room temperature for 2–20 minutes. RNA probes were detected with alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-digoxygenin Fab fragments (Roche) 1:2000, and visualized with NBT/BCIP in NTMT. After the reaction, sections were counter stained with eosin and cover slipped.

RNA probes were generated from plasmids containing sequences of Sox9, Collagen II, Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Autotaxin, Chordin, or Barx1 (kind gift of Cliff Tabin), Bapx1 (kind gift of Abigail Tucker), or Noggin (kind gift of Ed Laufer). Probes were made following Burke et al., 1995.

For the costal joint gene expression screen, HH29 metatarsophalangeal joint sections were mounted on the same slides as costal joint sections, to ensure that each joint was treated equally for gene expression analysis. Alternating sets of sections were mounted on separate slides so that sense controls could be used to evaluate the level of background for each probe.

Data acquisition

Digital images were obtained using a Spot RT3 camera and Spot Advanced Plus Software Version 4.7. Figures were assembled using Photoshop Elements software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Tulenko, Rebecca Shearman, and Patricia Thompson for laboratory assistance and helpful discussions during the course of this project. We also thank Charles Archer for discussion and insight. Additionally, the reviewers of this manuscript provided valuable suggestions that we feel improved its quality. We thank Dr. Cliff Tabin and Kim Burman for the kind gifts of Wnt14/9a, Gdf5, Chordin, Autotaxin, Sox9, and Barx1 clones. The Bapx1 clone was a kind gift from Dr. Abigail Tucker. The Noggin clone was a kind gift from Dr. Ed Laufer. This research was supported by the Wesleyan University Biology Department and NIH R15 HD050282 to ACB.

Contributor Information

B. B. Winslow, Wesleyan University

A.C. Burke, Email: acburke@wesleyan.edu, Wesleyan University, Biology Department, Middletown, CT, 06459,

References

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcrintion factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes & Development. 2002;16:2813–2828. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer CW, Dowthwaite GP, Francis-West P. Development of synovial joints. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:144–155. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer CW, Dowthwaite GP, Francis-West P. Joint Formation, in “Fins Into Limbs”. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press; 2007. p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller D, Klingensmith J, Shneyder N, Tran U, Anderson R, Rossant J, De Robertis EM. The role of chordin/Bmp signals in mammalian pharyngeal development and DiGeorge syndrome. Development. 2003;130:3567–3578. doi: 10.1242/dev.00581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow AJ, Bogardi JP, Ladher R, Francis-West PH. Expression of chick Barx-1 and its differential regulation by FGF-8 and BMP signaling in the maxillary primordia. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:291–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199904)214:4<291::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:85–89. doi: 10.1038/8792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet LJ, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Harland RM. Noggin, cartilage morphogenesis, and joint formation in the mammalian skeleton. Science. 1998;280:1455–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AC, Nelson CE, Morgan BA, Tabin C. Hox genes and the evolution of vertebrate axial morphology. Development. 1995;121:333–346. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zankl A, Niroomand F, Liu Z, Katus HA, Jahn L, Tiefenbacher C. Upregulation of ID protein by growth and differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) through a smad-dependent and MAPK-independent pathway in HUVSMC. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.03.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens LPAM. The Skeletal Kinematics of Lung Ventilation in Three Basal Bird Taxa (Emu, Tinamou, and Guinea Fowl) Journal of Experimental Zoology Part a-Ecological Genetics and Physiology. 2008;309A:1–14. doi: 10.1002/jez.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens LPAM. A Cineradiographic Study of Lung Ventilation in Alligator mississippiensis. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part a-Ecological Genetics and Physiology. 2009;311A:563–585. doi: 10.1002/jez.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig FM, Bayliss MT, Bentley G, Archer CW. A role for hyaluronan in joint development. J Anat. 1990;171:17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig FM, Bentley G, Archer CW. The spatial and temporal pattern of collagens I and II and keratan sulphate in the developing chick metatarsophalangeal joint. Development. 1987;99:383–391. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotwell PL, Mabee PM. Gene expression patterns underlying proximal-distal skeletal segmentation in late-stage zebrafish, Danio rerio. Developmental Dynamics. 2007;236:3111–3128. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowthwaite GP, Edwards JC, Pitsillides AA. An essential role for the interaction between hyaluronan and hyaluronan binding proteins during joint development. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:641–651. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowthwaite GP, Flannery CR, Flannelly J, Lewthwaite JC, Archer CW, Pitsillides AA. A mechanism underlying the movement requirement for synovial joint cavitation. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:311–322. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JC, Wilkinson LS, Jones HM, Soothill P, Henderson KJ, Worrall JG, Pitsillides AA. The formation of human synovial joint cavities: a possible role for hyaluronan and CD44 in altered interzone cohesion. J Anat. 1994;185 (Pt 2):355–367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell HB. The histogenesis of cartilage and bone in the long bones of the embryonic fowl. Journal of Morphology and Physiology. 1925;40:417–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry G, Giganti A, Coge F, Bertaux F, Thiam K, Boutin JA. Functional invalidation of the autotaxin gene by a single amino acid mutation in mouse is lethal. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3572–3578. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C. Respiration in Early Tetrapods-The Frog is a Red Herring. Evolution. 1970;24:723–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1970.tb01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluhak J, Mais A, Mina M. Tenascin-C is associated with early stages of chondrogenesis by chick mandibular ectomesenchymal cells in vivo and in vitro. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:24–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199601)205:1<24::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Day TF, Jiang X, Garrett-Beal L, Topol L, Yang Y. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is sufficient and necessary for synovial joint formation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2404–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1230704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger Hamilton. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. Journal of morphology. 1951:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann C, Tabin CJ. Wnt-14 plays a pivotal role in inducing synovial joint formation in the developing appendicular skeleton. Cell. 2001;104:341–351. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy C, Uwanogho D, Sharpe PT. Regulation and role of Sox9 in cartilage formation. Dev Dyn. 1999;215:69–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199905)215:1<69::AID-DVDY8>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TP, Spater D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Developmental Cell. 2005;8:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A, Hogg DA. The effects of paralysis on skeletal development in the chick embryo. I. General effects. J Anat. 1991;177:159–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humason GL. Animal Tissue Techniques. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman LH. Comparative vertebrate anatomy. Chicago: The university of chicago press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama E, Leatherman JL, Shimazu A, Nah HD, Pacifici M. Syndecan-3, Tenascin-C, and the Development of Cartilaginous Skeletal Elements and Joints in Chick Limbs. Developmental Dynamics. 1995;203:152–162. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsenmayer TF, Hendrix MJ. Monoclonal antibodies to connective tissue macromolecules: type II collagen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;92:440–446. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsenmayer TF, Trelstad RL, Toole BP, Gross J. The collagen of osteogenic cartilage in the embryonic chick. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;52:870–876. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino R, Macias D, Ganan Y, Economides AN, Wang X, Wu Q, Stahl N, Sampath KT, Varona P, Hurle JM. Expression and function of Gdf-5 during digit skeletogenesis in the embryonic chick leg bud. Dev Biol. 1999;206:33–45. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Yelon D, Stainier DY, Kimmel CB. Two endothelin 1 effectors, hand2 and bapx1, pattern ventral pharyngeal cartilage and the jaw joint. Development. 2003;130:1353–1365. doi: 10.1242/dev.00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic D. Development of the diarthrodial joints in the rat embryo. Am J Anat. 1978;151:475–485. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001510403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic DR. Development of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the chick embryo: morphological, ultrastructural and histochemical studies. Am J Anat. 1977;150:333–347. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman AF, Houweling AC, de Boer PA, Christoffels VM. Sensitive nonradioactive detection of mRNA in tissue sections: novel application of the whole-mount in situ hybridization protocol. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:1–8. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PD, Drachman DB. The role of movement in the development of joints and related structures: the head and neck in the chick embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1969;22:349–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalin AM, Greenlee TK, Jr, Sandell LJ. Collagen gene expression during development of avian synovial joints: transient expression of types II and XI collagen genes in the joint capsule. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:352–362. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oganesian A, Zhu Y, Sandell LJ. Type IIA procollagen amino propeptide is localized in human embryonic tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1469–1480. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne AC, Lamb KJ, Lewthwaite JC, Dowthwaite GP, Pitsillides AA. Short-term rigid and flaccid paralyses diminish growth of embryonic chick limbs and abrogate joint cavity formation but differentially preserve pre-cavitated joints. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2002;2:448–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici M, Iwamoto M, Golden EB, Leatherman JL, Lee YS, Chuong CM. Tenascin is associated with articular cartilage development. Dev Dyn. 1993;198:123–134. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001980206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici M, Koyama E, Iwamoto M. Mechanisms of synovial joint and articular cartilage formation: recent advances, but many lingering mysteries. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2005;75:237–248. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KW. A monograph of the structure and development of the shoulder-girdle and sternum in the vertebrata. London: Piccadilly; 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Pitsillides AA, Ashhurst DE. A critical evaluation of specific aspects of joint development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2284–2294. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle RD, Johnson RL, Laufer E, Tabin C. Sonic hedgehog mediates the polarizing activity of the ZPA. Cell. 1993;75:1401–1416. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree RB, Schoor M, Chen H, Marks ME, Harley V, Mishina Y, Kingsley DM. BMP receptor signaling is required for postnatal maintenance of articular cartilage. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell LJ, Morris N, Robbins JR, Goldring MB. Alternatively spliced type II procollagen mRNAs define distinct populations of cells during vertebral development: differential expression of the amino-propeptide. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:1307–1319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman RM. Growth of the pectoral girdle of the Leopard frog, Rana pipiens (Anura: Ranidae) J Morphol. 2005;264:94–104. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubin NH, Alberch P. A Morphogenetic Approach to the Origin and Basic Organization of the Tetrapod Limb. Evolutionary Biology. 1986;20:319–387. [Google Scholar]

- Später D, Hill TP, Gruber M, Hartmann C. Role of canonical Wnt-signalling in joint formation. Eur Cell Mater. 2006a;12:71–80. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v012a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Später D, Hill TP, O’Sullivan RJ, Gruber M, Conner DA, Hartmann C. Wnt9a signaling is required for joint integrity and regulation of Ihh during chondrogenesis. Development. 2006b;133:3039–3049. doi: 10.1242/dev.02471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber SM, Dawid IB. barx1 is necessary for ectomesenchyme proliferation and osteochondroprogenitor condensation in the zebrafish pharyngeal arches. Dev Biol. 2008;321:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm EE, Kingsley DM. Joint patterning defects caused by single and double mutations in members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family. Development. 1996;122:3969–3979. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribioli C, Lufkin T. The murine Bapx1 homeobox gene plays a critical role in embryonic development of the axial skeleton and spleen. Development. 1999;126:5699–5711. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherbee SD, Niswander LA. Mechanisms of Chondrogenesis and Osteogenesis in Limbs. In: Hall BK, editor. Fins into Limbs. Chigaco: The University of Chicago Press; 2007. pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J, Tucker AS. Fgf and Bmp signals repress the expression of Bapx1 in the mandibular mesenchyme and control the position of the developing jaw joint. Dev Biol. 2004;266:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E, Hargrave MR, Christiansen J, Cooper L, Kun J, Evans T, Gangadharan U, Greenfield A, Koopman P. The Sry-related gene Sox9 is expressed during chondrogenesis in mouse embryos. Nat Genet. 1995;9:15–20. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Ferguson CM, O’Keefe RJ, Puzas JE, Rosier RN, Reynolds PR. A role for the BMP antagonist chordin in endochondral ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:293–300. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]