Abstract

Patterns and correlates of self-perceptions of spirituality and subjective religiosity are examined using data from the National Survey of American Life, a nationally representative study of African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. Demographic and denominational correlates of patterns of subjective religiosity and spirituality (i.e., religious only, spiritual only, both religious/spiritual and neither religious/spiritual) are examined. In addition, the study of African Americans and Caribbean Blacks permits the investigation of possible ethnic variation in the meaning and conceptual significance of these constructs within the U.S. Black population. African Americans and Caribbean Blacks are more likely than Non-Hispanic Whites to indicate that they are “both religious and spiritual” and less likely to indicate that they are “spiritual only” or “neither spiritual nor religious.” Demographic and denominational differences in the patterns of spirituality and subjective religiosity are also indicated. Study findings are discussed in relation to prior research in this field and noted conceptual and methodological issues deserving further study.

Over the past several years, conceptual and methodological refinements of the construct of religious involvement have emphasized its multidimensional character—being comprised of a diverse range of public and private behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs (Ellison & Levin, 1998; Idler & George, 1998; Idler et al., 2003; Koenig, McCullough & Larson, 2001). Subjective religiosity, as one dimension of religious involvement, is thought to: 1) assess intrinsic aspects of religious commitment, 2) embody assessments of the centrality of religion to an individual, including self-characterizations as being religious and 3) be distinct from both public and private religious behaviors which may be influenced by behavioral norms and social expectations (Chatters, Levin & Taylor, 1992; Koenig et al., 2001). Empirical work on the construct of spirituality suggests that, while related to religious involvement generally, and subjective religiosity, in particular, it is nonetheless a separate construct. Beyond this general distinction, however, there is no common understanding or definition of what constitutes religion versus spirituality. The tendency to use these terms interchangeably, among social scientists and the general public alike, contributes to the lack of conceptual clarity. The term “spirituality” is often erroneously used in reference to public religious behaviors such as church attendance. Further, ideas as to what constitutes religion and spirituality have changed over time; characteristics and functions that have been previously associated with religion (e.g., individual focus) have been appropriated by the construct of spirituality (Zinnbauer et al., 1997; Zinnbauer, Pargament & Scott, 1999).

Current definitions of religion and spirituality often emphasize their differences from one another in terms of character, roles, and functions. Koenig and colleagues (Koenig et al., 2001) define religion as community-focused, formal, organized, and behaviorally-oriented and consisting of an organized system of beliefs, practices and rituals designed to facilitate closeness to God. In contrast, spirituality is more individualistic, less visible, more subjective, and less formal and is viewed as a personal quest for answers to ultimate questions about life, meaning, and relationships to the sacred (Koenig et al., 2001). Others suggest that religion and spirituality reflect the intrinsic vs. extrinsic meanings of religion in which religiosity or “religion” is concerned with more explicit content and extrinsic dimensions of worship, while spirituality pertains to the functional and intrinsic aspects of religion (Pargament, 1999; Roof, 1993, 2000). Finally, some argue that recent developments in society have fostered a split between religion and spirituality (Marler & Hadaway, 2002) whereby organized religious participation has been supplanted by an increased emphasis on spirituality. Spirituality, in turn, is considered superior in terms of personal benefits and outcomes, particularly for persons who are disaffected with formal, organized religion (Pargament, 1999).

Self-definitions of Religiosity and Spirituality

A slightly different line of research explores self-definitions of religiosity and spirituality and focuses on the relationships between these constructs. These assessments have similar frames of reference (i.e., self-attributions) and have robust face validity as measures of the underlying constructs. With respect to religious involvement, subjective religiosity most closely approximates the construct of spirituality, while at the same time making clear their distinctions. As such, comparing subjective religiosity and spirituality poses an interesting question as to how these factors are inter-related. One of the few studies (Zinnbauer, Pargament, Cowell, Rye & Scott, 1997) that directly examined how individuals define themselves—religious, spiritual, or both—used the following categories: 1) both religious and spiritual, 2) religious but not spiritual, 3) spiritual but not religious, and 4) neither spiritual nor religious Seventy-four percent of respondents categorized themselves as both religious and spiritual, 19% indicated that they were spiritual, but not religious, 4% indicated that they were religious, but not spiritual and 3% stated that they were neither religious nor spiritual. Self-definitions were differentially associated with religious behaviors and beliefs; those who viewed themselves as being spiritual only were less likely to participate in religious activities or hold traditional beliefs. Using the same framework in a national probability sample, Shahabi and colleagues (2002) found that half of the respondents (52%) indicated that they were both religious and spiritual, 10% indicated that they were spiritual and not religious, 9% were religious and not spiritual, and a full 29% were neither religious nor spiritual. Unfortunately, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Native Americans were combined into one “non-white” category for analysis, making it impossible to ascertain separate racial and ethnic group differences in religious/spiritual self-definitions. Scott’s study (2001) of adult Protestants (N = 2012) from states representing four US regions found that roughly 64% reported that they were religious and spiritual, 18% were spiritual only, 9% were religious only, and 8% were neither religious or spiritual.

Methodological and sampling issues in prior studies, including differences in sample types and composition (i.e., convenience, religious institutions) and question format (Marler & Hadaway, 2002), have an impact on reported levels of religiousness versus spirituality. Question format and wording (i.e., forced choice response formats) may unintentionally represent religiousness and spirituality as mutually exclusive categories (p. 290) and obscure those situations in which respondents define themselves as both religious and spiritual. In some studies, question formats constrain respondents to self-identify as being exclusively spiritual or religious (Roof, 1993), while in others (Princeton Religion Research Center, 2000; Zinnbauer et al., 1997) they chose statements that best describes them. The Princeton study used three response options: 1) religious, 2) spiritual, but not religious, and 3) neither, while Zinnbauer et al. (1997) used four exhaustive response options: 1) religious, but not spiritual, 2) spiritual, but not religious, 3) neither spiritual nor religious and 4) both spiritual and religious. Finally, Marler and Hadaway (2002) used separate questions in which respondents reported whether they considered themselves to be: 1) religious (Yes/No) and 2) spiritual (Yes/No) and derived four derived categories—religious only, spiritual only, religious and spiritual and neither. Interestingly, the oldest cohort of respondents were most likely to report that they were both religious and spiritual and least likely to indicate that they were spiritual only; the youngest age cohort was almost twice as likely to state they were neither religious nor spiritual.

Race/Ethnicity and Religiosity and Spirituality

A tradition of ethnographic and survey research indicates that religious concerns are particularly salient for African Americans (Taylor et al., 2004), as reflected in consistently high levels of religious involvement. These patterns, in part, reflect the important historical role of the Black Church and religious traditions in developing social capital and building individual and collective resources (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990; Nelsen & Nelsen, 1975; Taylor et al., 2004)within African American communities (e.g., independent educational, health, and social welfare institutions). The “civic tradition” of the Black Church acknowledges and is responsive to the experiences and circumstances of Blacks and highlights the role of religion and worship communities in shaping distinctive forms of communal worship and religious identities (Taylor et al., 2007). Although ethnic diversity within the African American population has grown substantially over the past several decades (Logan & Deane, 2003), the issue of ethnic heterogeneity within the Black racial category is largely ignored because race and ethnicity have been traditionally viewed as interchangeable (Bashi, 2007; Waters, 1999). Ethnically defined sub-groups such as Caribbean Blacks are essentially obscured, despite important differences between African Americans and Blacks of Caribbean descent, particularly in relation to demographic and economic profiles (Logan & Deane, 2003). Available ethnographic studies (Bashi, 2007; Waters, 1999) indicate high levels of religious involvement among Caribbean Blacks and that worship communities have a major influence in shaping religious behavior, values and ethno-religious identities (McAlister,1998). Further, Black Caribbean churches embodying their own distinctive civic traditions (Warner & Wittner, 1998) promote a sense of community belonging and provide tangible, psychological, and spiritual resources to assist immigrants in adapting to their new environments and in coping with difficult life problems and transitions (Bashi, 2007),

Scholarship on African American and Afro-Caribbean religious and spiritual traditions identifies several distinctive beliefs and worship practices that can be traced to a common West African cultural heritage and worldview, as well as contact with North American missionary initiatives (Maynard-Reid, 2000). These common elements include a rich vocabulary and discourse concerning the presence of the Holy Spirit in one’s life, ecstatic manifestations of and possession by the Holy Spirit (e.g., clapping, dancing, singing) as an important feature of worship, direct, unmediated communication with the Divine through individual (i.e., conversational) and communal prayer (Krause & Chatters, 2005) and congregational activities, collective and participatory worship styles, and the prominence of spontaneity, improvisation, and informality (vs. formality) as elements of worship services. In sum, the sacred life of persons of African descent in the New World is characterized by several distinctive features including the centrality of worship communities as civic institutions and the prominence of spirituality or Spirit-focused beliefs and practices as an integral component of individual and corporate religious expression and identity. Accordingly, we anticipate that African Americans and Caribbean Blacks will be similar in their endorsements of both religious and spiritual identities in their self-definitions.

Focus of the Present Study

The present study examining race and ethnicity differences in self-definitions of spirituality and religiosity reflects several innovations in sampling and item methodology. First, as a departure from prior work conducted primarily in non-probability samples of the general population or specialized subgroups which are predominantly, if not exclusively, Caucasian, the study uses a large, nationally representative sample of African American, Caribbean Black and non-Hispanic White adults. Notably, this is the first investigation of these issues within a national Caribbean Black sample. Second, independent questions assess whether respondents consider themselves spiritual and religious, which are then combined to obtain the self-definition. Finally, the analyses control for demographic and denominational factors that have independent effects on religiosity/spirituality and are differentially distributed across the three groups.

METHODS

Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research, in cooperation with the Institute of Social Research’s Survey Research Center. A total of 6,082 face-to-face interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older, including 3,570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic whites, and 1,621 Blacks of Caribbean descent. The NSAL includes the first major probability sample of Caribbean Blacks ever conducted, who, for the purposes of this study, are defined as persons who trace their ethnic heritage to a Caribbean country, but who now reside in the United States, are racially classified as Black, and who are English-speaking (but may also speak another language). The overall response rate was 72.3%. Response rates for individual subgroups were 70.7% for African Americans, 77.7% for Caribbean Blacks, and 69.7% for non-Hispanic Whites. Final response rates for the NSAL two-phase sample designs were computed using the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAAPOR) guidelines (for Response Rate 3) (AAPOR, 2006). The interviews were face-to-face and conducted within respondents’ homes; respondents were compensated for their participation. The data collection was conducted from 2001 to 2003 (see Jackson et al., 2004 and Herringa et al., 2004 for a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample).

The African American sample is the core sample of the NSAL and consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSUs). The Caribbean Black sample was selected from two area probability sample frames: the core NSAL sample and an area probability sample of housing units from geographic areas with a relatively high density of persons of Caribbean descent. For both the African American and Caribbean Black samples, it was necessary for respondents to self-identify their race as black. Those self-identifying as black were included in the Caribbean Black sample if they answered affirmatively when asked if they were of West Indian or Caribbean descent, said they were from a country included on a list of Caribbean area countries presented by the interviewers, or indicated that their parents or grandparents were born in a Caribbean area country. Seven out of 10 Caribbean Blacks emigrated from an English-speaking Caribbean country (e.g., Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad & Tobago), fourteen percent emigrated from a Spanish-speaking Caribbean country (e.g., Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba), and thirteen percent emigrated from Haiti.

Measures

Self-rated spirituality and religiosity were measured by two questions: “How spiritual would you say you are?” and “How religious would you say you are?” (response categories were: very, fairly, not too, or not at all). Both questions were recoded by combining the response categories: (1) very and fairly vs. (2) not too and not at all. This resulted in two items, self-rated spirituality: Yes/No and self-rated religiosity: Yes/No which were then combined into a single variable with four categories reflecting persons who were: 1) both spiritual and religious, 2) religious only, 3) spiritual only, or 4) neither spiritual nor religious. Demographic factors such as race/ethnicity, age, gender, marital status, education, family income, and region are examined as correlates. Income is coded in dollars. In the multivariate analysis income has been divided by 5000 in order to increase effect sizes and provide a better understanding of the net impact of income. Missing data for family income were imputed for 773 cases (12.7% of the total NSAL sample) and missing data for education were imputed for 74 cases (1.2% of the total NSAL sample). Imputations were done using Answer Tree in SPSS. Religious affiliation is measured by the question: “What is your current religion?” Over 40 reported affiliations were recoded into seven categories: Baptists, Methodist, Pentecostal, Catholic, Other Protestant (e.g., Lutheran, Presbyterian), Other Religions (e.g., Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim), and None.

Analysis Strategy

Cross-tabulations illustrate race and ethnic differences in the demographic variables and patterns of spirituality/religiosity. All analyses were conducted using Stata 9 SE which uses the Taylor expansion approximation technique for calculating the complex-design based estimates of variance. Multi-nominal logistic regression analysis was conducted using svy: mlogit command and relative risk ratios are presented. Relative Risk Ratios are similar to odds ratios; odds ratios compare the relative odds of an event happing whereas relative risk compares the probability of one event against another. In essence one is for odds whereas the other is for probability. The interpretation of relative risk ratios are the same as odds ratios with 1 indicating no relationship and values greater than one indicating positive relationships and less than one indicating negative relationships (see Dixon, 2001 for a more detailed comparison of odd ratios and relative risk ratios). To obtain results that are generalizable to the national population, this analysis utilizes analytic weights. Weights in the NSAL data account for unequal probabilities of selection, non-response, and post-stratification such that respondents are weighted to their numbers and proportions in the full population (Herringa et al., 2004). Additionally, standard error estimates that are corrected for sample design (i.e., clustering and stratification) are utilized.

Sample Characteristics

NSAL respondents range in age from 18 to 94 years (M = 43.57) and a slight majority of them are women (54.12%). One of four respondents is married (40.35%), one quarter are never married (26.81%), one in ten are divorced (12.30%) and the remainder (21.54%) are separated, widowed or living with a partner. Slightly more than half (54.47%) of the sample reside in the South. The average imputed family income is $42,455 and the average number of years of education is 12.89. Overall, one-third of the respondents are Baptists (34.25%), 13.46% are Catholic, 6.29%, are Methodists, 4.27% are Pentecostal, 4.42% are other religions (e.g., Muslims, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish), 22.21% are Other Protestant groups and 13.06% did not indicate a current religious denomination. As indicated in Table 1, the NSAL sub-samples are distinctive from one another in several respects. Of the three groups, Non-Hispanic Whites have the highest mean family income and are more likely to be married. More than half of Caribbean Blacks reside in the Northeast and African Americans are twice as likely to identify as Baptists, as compared to Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. In analysis not shown, Caribbean blacks are more likely to be Seventh Day Adventist and Episcopalian than the other two groups.

Table 1.

Distribution of the Study Variables by Race and Ethnicity

| DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES | MEANS (S.E.) OR PERCENTAGES | Complex Design Based F-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | Black Caribbeans | Non-Hispanic Whites | ||

| Age | 42.32 (.52) | 40.27 (.84) | 44.98 (1.34) | 4.65* |

| N | 3570 | 1621 | 891 | |

| Education | 12.43 (.086) | 12.88 (.146) | 13.31 (.292) | 6.81** |

| N | 3570 | 1621 | 891 | |

| Income | 36,832 (1,487) | 47,044 (3,416) | 47,355 (3,788) | 6.91** |

| N | 3570 | 1621 | 891 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44.03 | 50.87 | 47.26 | 2.07 |

| Female | 55.97 | 49.13 | 52.74 | |

| N | 3570 | 1621 | 891 | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 32.91 | 37.56 | 47.36 | 5.91** |

| Partner | 8.74 | 12.58 | 6.59 | |

| Separated | 7.16 | 5.36 | 3.10 | |

| Divorced | 11.75 | 9.29 | 13.06 | |

| Widowed | 7.89 | 4.28 | 7.83 | |

| Never married | 31.55 | 30.92 | 22.05 | |

| N | 3553 | 1616 | 887 | |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 15.69 | 55.69 | 22.67 | 4.58** |

| North Central | 18.81 | 4.05 | 7.96 | |

| South | 56.24 | 29.11 | 54.60 | |

| West | 9.25 | 11.14 | 14.76 | |

| N | 3570 | 1621 | 891 | |

| Denomination | ||||

| Baptist | 49.08 | 20.52 | 21.18 | 13.53*** |

| Methodist | 5.87 | 3.17 | 6.90 | |

| Pentecostal | 8.61 | 8.70 | 3.88 | |

| Catholic | 5.95 | 18.67 | 20.21 | |

| Other Protestant | 17.7 | 32.65 | 25.77 | |

| Other Religion | 2.25 | 3.56 | 6.54 | |

| No Religion | 10.51 | 12.73 | 15.50 | |

| N | 3568 | 1613 | 888 | |

| Self-Ratings of Religiosity and Spirituality | ||||

| Both religious and spiritual | 81.24 | 76.92 | 62.89 | 14.47*** |

| Religious only | 2.84 | 4.59 | 3.15 | |

| Spiritual only | 7.79 | 11.17 | 19.07 | |

| Neither religious/spiritual | 8.11 | 7.30 | 14.88 | |

| N | 3546 | 1608 | 886 | |

p < .05;

p< .01;

p < .001

RESULTS

Overall, 8 out of 10 respondents (79.4%) characterize themselves as being both spiritual and religious, while 3.2% indicate that they are religious only, 13.5% report that they are spiritual only, and 8.2% indicate that they are neither spiritual nor religious. The bivariate associations (Table 1) for patterns of spirituality and religiosity across African Americans Caribbean and Non-Hispanic Whites indicate that a larger percentage of African Americans (81.2%) characterize themselves as being both spiritual and religious, followed by Caribbean Blacks (76.9%) and non-Hispanic Whites (62.9%). Conversely, a larger percentage of non-Hispanic Whites (19.1%) indicate they are spiritual only (7.8% for African Americans and 11.2% for Caribbean Blacks) or that they are neither spiritual nor religious (14.9% as compared to 8.1% for African Americans and 7.3% for Caribbean Blacks). Table 2 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis of patterns of self-rated spirituality and religiosity. The format and interpretation of this analysis is similar to dummy variable regression and consists of contrasts between a comparison and an excluded category. However, comparisons between selected categories and the excluded category involve both the dependent variable and selected independent variables (as opposed to only selected independent variables in standard dummy variable regression). The four-category dependent variable yields six unique comparisons of self-rated spirituality and self-rated religiosity: 1) religious only vs. both spiritual and religious, 2) spiritual only vs. both spiritual and religious, 3) neither vs. both spiritual and religious, 4) spiritual only vs. religious only, 5) spiritual only vs. neither, and 6) religious only vs. neither. Given our particular theoretical interest and the fact that multinomial regression analysis provides redundant results, only three comparisons are presented: a) religious only versus both spiritual/religious, b) spiritual only versus both spiritual/religious, and c) neither versus both religious/spiritual.

Table 2.

Estimated Net Multinomial Regression Effects of Demographic Factors and Denominational Affiliation on Self-Rated Patterns of Spirituality and Religiosity1

| Model 1: Religious Only Compared to Both | Model 2: Spiritual Only Compared to Both | Model 3: Neither Compared to Both | Model 4: Religious Only Compared to Both | Model 5: Spiritual Only Compared to Both | Model 6: Neither Compared to Both | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caribbean Black | 1.07 | .861 | .638 | 1.02 | 1.01 | .280*** |

| White | 1.29 | 3.06*** | 2.46 *** | .559 | 2.35*** | 1.71*** |

| Age | .979 | .980*** | .983* | .979 | .980*** | .983* |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | .629 | .481*** | .351*** | .585* | .479*** | .344*** |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Divorced | .746 | 1.51 | 1.55 | .665 | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Widowed | 1.43 | .480 | 1.45 | 1.35 | .494 | 1.46 |

| Separated | .443 | 3.07 * | 1.40 | .390 | 3.09* | 1.37 |

| Co-Habit | .450 | 1.77 | 2.11* | .415 | 1.75 | 2.04 |

| Never Married | 1.19 | 1.99* | 1.26 | 1.08 | 2.01* | 1.25 |

| Income | 1.02 * | 1.01 | .997 | .950 | .995 | .962 |

| Education | .976 | 1.06 | .983 | .993 | 1.06 | .985 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 2.06 | 2.30*** | 1.94* | 2.38 | 2.38*** | 2.01** |

| North Central | .694 | 1.49* | 1.34 | .719 | 1.52* | 1.38 |

| West | 1.23 | 1.41 | .811 | 1.34 | 1.45 | .831 |

| Denomination | ||||||

| Methodist | 1.00 | 1.05 | .915 | .970 | 1.03 | .906 |

| Pentecostal | .527 | 2.10 | .882 | .496 | 2.07 | .867 |

| Catholic | 1.48 | 1.86* | 1.46 | 1.38 | 1.82 | 1.44 |

| Other Protestant | .687 | 1.94** | .893 | .651 | 1.91** | .887 |

| Other Religion | .378 | 3.29*** | 4.70*** | .352 | 3.23*** | 4.64** |

| No Affiliation | 1.34 | 10.91*** | 8.79*** | 1.28 | 10.7*** | 8.59*** |

| Income x Caribbean Black | --- | --- | --- | 1.01 | .989 | 1.08* |

| Income x White | --- | --- | --- | 1.10* | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| F = 205.69*** | F = 526.29*** | |||||

| N = 6007 | N = 6007 | |||||

Several of the independent variables in this analysis are represented by dummy variables. Race/Ethnicity, African American is the Excluded Category; Gender, 0 = Male, 1 = Female; Marital Status, married is the excluded category; Region, South is the excluded category; Denomination, Baptist is the excluded category. Income has been Income is coded in dollars and has been divided by 5000. Relative Risk Ratios are presented.

p < .05;

p< .01;

p < .001

Table 2 presents the results of multinomial regression analyses contrasting individuals who indicate that they are both spiritual and religious with those who indicate that they are: a) religious only (Model 1), b) spiritual only (Model 2), and, c) neither (Model 3). In Model 1, income is the only variable that achieves significance (although this relationship is very small). Respondents with higher incomes are more likely to indicate that they are religious only than to indicate that they are both spiritual and religious. Race, age, gender, region, marital status and denomination are all significantly associated with the likelihood of being spiritual only as compared to being both spiritual and religious (Model 2). Non-Hispanic whites are more likely than African Americans, older respondents are less likely than younger respondents, and women are less likely than men to indicate that they are spiritual only as opposed to both spiritual and religious. Regional differences indicate that respondents in the Northeast and the North Central regions are more likely than those in the South to report being spiritual only. For marital status groups, separated and never married respondents are more likely than married respondents to indicate that they are spiritual only. Lastly, Catholics, respondents who identify with other Protestants, other religions or who have no current religious denomination are more like than Baptists to indicate that they are spiritual only. Model 3 presents the coefficients for the likelihood of being neither spiritual nor religious, as compared to being both spiritual and religious. Race, age, gender, marital status, region, and denomination are significantly associated with the likelihood of being neither as opposed to both religious and spiritual. Whites were two and one half times more likely than African American to indicate that they are neither religious nor spiritual. Men and younger respondents are less likely than their counterparts to indicate that they are neither spiritual nor religious. Respondents who reside in the Northeast are more likely than Southerners and persons who live with their partner (cohabitors) are more likely than marrieds to indicate that they are neither spiritual nor religious. Lastly, respondents who identify with other religions and those without a current religious affiliation are more likely than Baptists to report that they are neither spiritual nor religious.

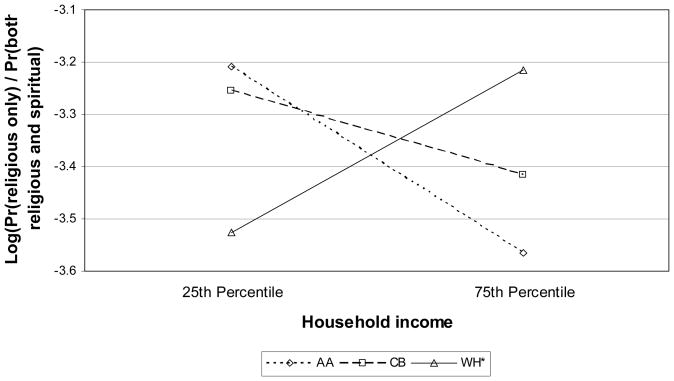

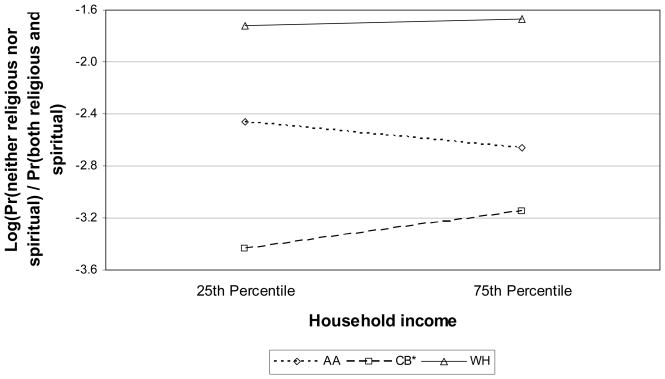

Interactions between: 1) race/ethnicity and income and, 2) race/ethnicity and education were tested. The interaction with education was not significant but the interaction between race/ethnicity, income and the dependent variable is significant. The significant interactions are shown in Models 4 and 6 in Table 2. They are more clearly displayed in the plots in Figures 1 and 2. In both figures the effect of income on the dependent variable by race/ethnicity is presented. Figure 1 displays the significant interaction in Model 4 and Figure 2 displays the interaction in Model 6. Figure 1 indicates that for whites higher income respondents are more likely to indicate that they are religious only (compared to both religious and spiritual) whereas for African Americans and to a lesser degree Caribbean Blacks higher income respondents are less likely to say that they are religious only (it is important to note that very few respondents indicated that they were religious only, so these findings should be viewed in that context). Figure 2 indicates that although there is a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and income on the likelihood of respondents indicating neither as opposed to both spiritual and religious, this interaction is not especially strong. Non-Hispanic whites were more likely to report that they were neither religious nor spiritual, followed by African Americans and then Caribbean Blacks. The relationship between income and the likelihood of reporting neither is slightly negative for African Americans, but slightly positive for Black Caribbeans.

Figure 1.

Moderating Effect of Race/Ethnicity on Income and Religiosity/Spirituality, Controlled for other demographics and Denominations

Figure 2.

Moderating Effect of Race/Ethnicity on Income and Religiosity/Spirituality, Controlled for other demographics and Denominations

Note: * significant at 0.05 level compared to African Americans. Dependent Variable is the log of the probability ratio of religious only vs. both religious and spiritual (Figure 1) and neither vs. both religious and spiritual (Figure 2).

Discussion

Overall, the findings from this national probability sample indicate that Americans, irrespective of race/ethnicity, generally characterize themselves as both spiritual and religious. Overall, roughly 72% characterized themselves as being both religious and spiritual, while approximately 13% of respondents indicated that they were spiritual only. The observed rates are largely comparable with previous research (Scott, 2001; Zinnbauer et al., 1997), although higher than the percentages reported in Shahabi et al.’s (2002) national sample. Although there has been considerable discussion concerning the rise of spirituality and the decline of religiosity (see Marler & Hadaway, 2002 and Pargament 1997), the findings from this cross-sectional study do not support this characterization and indicate that most Americans identify as being both spiritual and religious (Taylor et al., 2004). As suggested in the bivariate analyses and confirmed in the multivariate context, African Americans were significantly more likely than Whites to indicate that they were both spiritual and religious and less likely to report that they were spiritual only or neither religious or spiritual. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating significantly higher levels of religious participation and commitment among African Americans than Whites (Krause & Chatters, 2005; Taylor, Chatters, Jayakody, & Levin, 1996). African Americans and Caribbean Blacks had comparable patterns of spirituality and religiosity, consistent with previous analyses among older adults (Taylor, Chatters, & Jackson, 2007). We argued here that noted similarities between African Americans and Caribbean Blacks can be partly attributed to comparable worship traditions in which spiritual discourse and practice occupy a prominent place in both individual and collective religious expression. Furthermore, due to their civic traditions, churches maintain active involvement in the development and maintenance of human, social and political capital within African American (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990; Taylor et al., 2004) and Caribbean Black immigrant (Maynard-Reid, 2000; McAlister, 1998; Waters, 1999) communities and are instrumental in patterning religious involvement and sentiments (Krause & Chatters, 2005).

As indicated in Figures 1 and 2 there were two significant interactions between race/ethnicity and income on the patterns of spirituality and subjective religiosity. The findings in Figure 1 indicate that identification as religious only (as compared to both religious and spiritual) is characteristic of whites who possess higher incomes and African Americans and Caribbean Blacks who have lower incomes. Although the category of religious only is relatively small it is clear that they are a unique group that deserves more research. The findings in Figure 2 indicate that although there is a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and income on the probability of being neither spiritual nor religious, this effect is not very strong. Collectively these findings suggest that in future research it may be important to investigate the possible role of income level in understanding race/ethnicity differences in religiosity and spirituality.

Consistent with previous work indicating pervasive gender and age differences in religious involvement (Taylor et al., 2004), men and younger persons were more likely than their counterparts to characterize themselves as spiritual only or neither spiritual nor religious. Married persons were more likely to view themselves as being both religious and spiritual as compared to spiritual only (as compared to separated and never married) or neither religious or spiritual (as compared to cohabitators). Regional differences indicated that Southerners were more likely than persons residing in the Northeast to indicate that they are both religious and spiritual (compared to spiritual only and neither) and more likely than those in the North Central to indicate that they were both religious and spiritual (as compared to spiritual only). These findings are compatible with prior work demonstrating a consistent pattern of elevated levels of religious participation among residents of the South (Taylor et al., 2004). The one significant socioeconomic status finding indicated that persons with higher incomes were more likely to characterize themselves as religious only as opposed to both spiritual and religious. With respect to denomination, Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals and Catholics were similar with respect to self-characterizations as religious and spiritual. Respondents who identified another Protestant denomination, were of another faith, or did not report a current denomination, were less likely than Baptists to report that they were both spiritual and religious; persons of another faith and the unaffiliated were more likely than Baptists to indicate that they were neither spiritual nor religious.

The study findings prompt several observations and questions. First, the overall percentage of persons indicating a religious/spiritual identity is roughly comparable to Zinnbauer et al., (1997), but higher than Scott (2001) and Shahabi et al., (2002). Focusing only on non-Hispanic Whites, the percentage claiming a religious/spiritual identity was comparable to Scott (Protestant sample), but higher than Shahabi et al., (2002). Although differences in both study samples and question formats make direct comparisons problematic, the use of independent assessments of religiosity and spirituality (as opposed to forced choice/yoked response formats) may have yielded higher rates of reporting both a religious and spiritual identity (Marler & Hadaway, 2002). Future studies incorporating separate question formats and conducted within diverse study samples may clarify these questions. Second, the present study indicated that non-Hispanic Whites, younger persons and men were most likely to self-identify as spiritual only or neither spiritual/religious—the same groups that, in other studies, are less likely to be invested in other forms of religious involvement (Taylor et al., 2004). Direct examination of the broader behavioral and attitudinal correlates of different religious/spiritual identities, within and across diverse population groups, may confirm Zinnbauer et al.’s (1997) suggestion that persons identifying as spiritual only are less likely to participate in religious activities or hold traditional beliefs. One study demonstrating the complexity of the associations between religious identification and behaviors found that 52% of African American women who were unaffiliated and 68% of those who did not attend religious services, nonetheless reported that they were either very or fairly religious (Mattis, Taylor & Chatters, 2001). These findings further suggest that survey methodologies and question formats focusing exclusively on religious involvement may be insufficient for assessing the experiences of persons for whom spirituality is the primary identity. Finally, the present findings, together with prior ethnographic research, suggest that spiritual and religious identities are compatible and seemingly inseparable aspects of the sacred experience of many African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Further, although spirituality among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks appears to share some elements (e.g., subjective, less formal) of current conceptualizations of this construct (Koenig et al., 2001), it departs in important ways by being a distinctively communal and shared experience and a visible and palpable manifestation of the action of spirit in the physical world (Maynard-Reid, 2000). Given the noted prominence of beliefs and worship practices that are focused on the Holy Spirit among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks, ideas about what it means to be a spiritual person and the significance of spirituality vis-à-vis religiosity may be very different for these religious traditions. The distinctions between spiritual-only vs. religious-only identities may be especially pertinent for Caribbean Blacks because both African-derived (e.g., Orisha, Vodun) religions and Christian worship traditions (e.g., Spiritual Baptists) with pronounced spiritual foundations and focus have been historically stigmatized by traditional mainline churches (Maynard-Reid, 2000). These findings and observations point to the need for continued study as to what it means to be religious and spiritual and how these conceptual meanings vary across and within racial/ethnic groups. In conclusion, this initial study of spirituality and religiosity found both commonalities and differences across race and ethnicity in the relative rates of religious/spiritual identities, confirmed the operation of key demographic and denominational factors in patterning these characterizations, and identified a number of conceptual and methodological issues for further inquiry.

Acknowledgments

The data collection on which this study is based was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging to Drs. Chatters and Taylor (R01-AG18782) and Drs. Jackson and Taylor (P30-AG15281). Address correspondence to Linda Chatters, School of Public Health, 1420 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, Phone: (734)647-3178, Fax: (734) 763-7379, chatters@umich.edu.

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4. Lenexa, Kansas: AAPOR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bashi VF. Survival of the knitted: Immigrant social networks in a stratified world. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Antecedents and dimensions of religious involvement among older Black adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1992;47:S269–S278. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.s269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory and future directions. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:700–20. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, George LK. What sociology can help us understand about religion and mental health. In: Koenig HG, editor. Handbook of religion and mental health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, Pargament KI, Powell LH, Underwood LG, Williams DR. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging. 2003;25(4):327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RN, Taylor RJ, Trierweiler SJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H, McCullough M, Larson D. The handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Chatters LM. Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion. 2005;66(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Deane G. Report from the Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research. State University of New York; Albany, NY: 2003. Black diversity in metropolitan America. [Google Scholar]

- Marler PL, Hadaway CK. “Being religious” or “Being spiritual” in America: A zero-sum proposition? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(2):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard-Reid PU. Diverse worship: African-American, Caribbean and Hispanic perspectives. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister E. The Madonna of 115th street revisited: Vodou and Haitian Catholicism in the age of transnationalism. In: Warner RS, Wittner JG, editors. Gatherings in diaspora: Religious communities and the new immigration. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1998. pp. 123–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen HM, Nelsen AK. Black church in the sixties. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 1999;9:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Princeton Religion Research Center. Americans remain very religious, but not necessarily in conventional ways. Emerging Trends. 2000;22(1):2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Roof WC. A generation of seekers: The spiritual journeys of the baby boom generation. San Francisco: CA: Harper-Collins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roof WC. Spiritual marketplace: Baby boomers and the remaking of American religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scott RO. Spirituality and Health. Spring: 2001. Are you religious or are you spiritual: A look in the mirror; pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabi L, Powell LH, Musick M, Pargament KI, Thoresen CE, Williams D, Underwood L, Ory MA. Correlates of self-perceptions of spirituality in American adults. Annuals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(1):59–68. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SD. Understanding the odds ratio and the relative risk. Journal of Andrology. 2001;22(4):533–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jayakody R, Levin JS. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2007;62:S238–S250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC. Black identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Warner RS, Wittner JG, editors. Gatherings in diaspora: Religious communities and the new immigration. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI, Cole B, Rye MS, Butter EM, Belavich TG, Hipp KM, Scott AB, Kadar JL. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36(4):549–564. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI, Scott A. The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality. 1999;67(6):889–919. [Google Scholar]