Abstract

This study utilizes data from the older African American sub-sample of the National Survey of American Life (n=837) to examine the sociodemographic and denominational correlates of organizational religious involvement among older African Americans. Six measures of organizational religious participation are utilized, including two measures of time allocation for organized religious pursuits. The findings indicate significant gender, region, marital status and denominational differences in organizational religiosity. Of particular note, although older black women generally displayed higher levels of religious participation, older black men spent more hours per week in other activities at their place of worship. The findings are discussed in relation to prior work in the area of religious involvement among older adults. New directions for research on religious time allocation are outlined.

Keywords: church attendance, religious time use, time allocation

Since the publication of the first article on religious participation among older Black adults using the National Survey of Black Americans dataset (Taylor 1986), substantial progress has been made in this area. Due to the lack of research in this area at the time, a fair amount of the literature review for that study was focused on the related areas of social participation and involvement in voluntary activities and not on religious participation, per se. Further, many of the studies that were cited were based on convenience samples (Taylor 1986). In the ensuing years, considerable progress has been made in understanding the nature and extent of religious involvement among older Black adults. The present investigation examines the correlates of organizational religious participation (e.g., church membership, church attendance) among older African Americans within a large national sample. In addition, this study examines several novel measures of time investment and use in relation to church activities.

African Americans generally and, older African Americans in particular, display high levels of religious involvement (Krause 2006; Krause and Chatters 2005; Levin, Taylor and Chatters 1994; Taylor, Chatters and Levin 2004; Taylor, Chatters and Jackson 2007). This is evident across a variety of religious indicators, including church membership rates, frequency of public behaviors (e.g., church attendance), private devotional practices (e.g., prayer and reading religious materials), and subjective appraisals of religiosity and spirituality. Research on adult samples (18 years and older) demonstrates that age has strong, positive effects on religious involvement across numerous indicators. Older African Americans report higher levels of religious participation than their younger counterparts (Taylor et al. 2004). These findings are relatively strong and consistent in analyses involving the National Survey of Black Americans (Chatters and Taylor 1989; Ellison and Sherkat 1995; Levin and Taylor 1993; Levin, Taylor and Chatters 1995;Taylor 1988), as well as in analysis using other surveys (Chatters, Taylor and Lincoln 1999). Together, these findings suggest that the religious experiences of African Americans are characterized by both relatively high levels of overall religious involvement and, further, a general linear and positive age relationship whereby religious involvement is highest among persons of advanced age.

Time Allocation and Organizational Religious Participation

Time use studies are widespread in economics where there is interest in how individuals allocate their time between work, leisure and other activities (Becker 1965; Juster and Stafford 1991). Research in social gerontology and family studies has increasingly adopted this methodology to explore general time use patterns among elderly adults (Gauthier and Smeeding 2003), as well as more specific questions regarding the amount of time allocated to housework (Gauthier and Smeeding 2003) and adult children’s time investments in assisting elderly parents (Ladika and Ladika 2001; Wong, Kitayama and Soldo 1999).

Time use studies in the field of gerontology (Gauthier and Smeeding 2003) have found that, in comparison to younger adults, older adults spend less time in paid employment and physically demanding leisure activities (e.g., playing sports), and spend more time in family-related activities and passive leisure activities (e.g., watching television, listening to the radio). This body of research, however, generally has not explored the amount of time that older individuals devote to religious pursuits. For instance, individual studies typically do not specifically assess religious activities (Gershuny and Sullivan 2003) or, if examined, include them in a broader category that encompasses general social activities (Gauthier and Smeeding 2003). There are a few notable exceptions. Two recent studies explicitly examine the amount of time devoted to religious activities. Bouma and Lennon (2003) investigated the amount of time allocated to religious and spiritual activities among a national sample of Australians. A particular strength of their work was that they examined church attendance, as well as other religious activities such as prayer and reflection. Their findings indicated that on “an average day” 10% of all Australian households engaged in some form of religious activity. Roughly equal amounts of time were allocated to religious activities as for attending sporting and cultural events.

Hofferth and Sandberg (2001) examined the time use patterns of children under the age of 13. They found that children averaged a little more than 1 hour per week at church services and church related meetings. However, children in Black families and children in families with an older head of household spent more time in church. These findings are consistent with research on demographic differences in religious participation which indicates that older adults and African Americans report more frequent church attendance than their counterparts (Taylor et al. 2004).

Probably the most recognized research on time use with regards to religious activities is the work of Presser and associates (Presser and Stenson 1998; Presser and Chaves 2007) on weekly service attendance. In their research, respondents were asked to describe all of their primary activities on the preceding day from midnight to midnight. Analysis was restricted to interviews that were conducted on Monday to estimate the rates of service attendance on Sunday. Three major conclusions can be drawn from their studies. First, rates of weekly service attendance declined from the 1950’s to 1990, but have remained stable since 1990. Second, time use data provides lower estimates of service attendance than are found in general polls and surveys. Lastly, in their studies of time use, the demographic correlates of service attendance are the same as those reported in standard social surveys.

Findings from qualitative research indicate considerable variability in the amount of time spent in formal religious services (Taylor et al. 2004). For some individuals, involvement in religious services may involve only 1 to 2 hours, whereas for others a typical Sunday may involve 4 or more hours. Further, there is considerable individual variation in the amount of time that a person spends in organized religious pursuits, even within the same congregation. For instance, Sunday activities could include an early morning service (8–9:30), Sunday school from 9:30 to 11, a later morning service from 11–1:30 p.m. and an early dinner and late afternoon service. Person A may attend the 8:00–9:30 a.m. service and Sunday school classes from 9:30–11 a.m. for a total of 3 hours. Person B may only attend the 8:00 am service (a total of 1.5 hours), while Person C may attend the longer late morning service from 11:00 to 1:30 (a total of 2.5 hours). Finally, Person D may attend Sunday school classes and the 11:00 service (a total of 4 hours). Even though all of these individuals attend the same church, the amount of time they spend in religious services and associated activities varies substantially. Finally, there are important denominational differences in the structure, organization and frequency of religious services (Newport 2006). Many congregations (e.g., Baptist, Church of God in Christ) observe the tradition of afternoon services (at 3 or 4pm) and the sharing of a meal conducted in fellowship with other local congregations. This may be followed by Sunday evening service conducted back at the home church from 6:30 to 8:30 pm or later.

Given these prior insights on variations in time use in religious activities, we have included measures of: 1) the amount of time spent in religious services (on a typical Sunday) and 2) the amount of time spent at the place of worship during the week (not including religious services). These items use a format that is consistent with research on time allocation (e.g., the number of hours per week a person spends in paid work) and have been used in other surveys such as the National Survey of Families and Households (Goodman 2002). These two items are not as comprehensive as the more labor intensive and costly diary methods (Gauthier and Smeeding 2003). However, they are superior to other time use measures found in other major surveys (Wong et al. 1999) that involve a simple dichotomous format in which respondents indicate whether they have reached a threshold number of hours devoted to a given activity for a specified time period (for example, whether or not a person spent more than 100 hours in the last 12 months caring for an elderly parent).

The present investigation utilizes the older African American subsample of the National Survey of American Life to explore the correlates of several indicators of organizational religious participation. In particular, it examines the demographic and denomination correlates of never attending religious services since the age of 18, overall church attendance, church membership, frequency of participating in congregational activities and two measures of time allocation (i.e., time spent in religious services vs. time spent in other activities at place of worship). The present investigation has several advantages over previous research. First, organizational religious participation is an important area of investigation that has been associated with a wide range of outcomes in a variety of fields, including access to social support networks and resources within religious congregations, overall higher assessments of physical and mental health (Taylor et al. 2004) including lower rates of depression (Koenig, McCullough and Larson 2001), and decreased rates of mortality especially among African Americans (Hummer et al. 2004). Several studies in political sociology have examined the impact of organizational religious behavior such as attendance and congregational activities on voting behavior (Brown 2003; Brown, McKenzie and Taylor 2003; Taylor and Thornton 1993). Across these studies, measures of organizational religious participation are consistently related to the outcome variables of interest, whereas measures of private religious devotional activities (e.g., praying, reading religious materials) demonstrate weak and inconsistent relationships. Organizational religiosity is particularly important for African Americans because several researchers argue that their lower rates of depression (Williams et al. 2007), and suicide (see for example Joe, Romer and Jamieson 2007; Poussaint and Alexander 2000) are primarily due to their high levels of religious participation. The present study’s focus on several measures, provides a more detailed examination of different facets of organizational religious participation.

Second, this investigation explores the actual amount of time older persons devote to organizational religious activities. To our knowledge, this is the first time use study in the area of religion and aging. The absence of time use studies on this topic is somewhat surprising given the recognized importance of religion and religious involvement for older persons. The current study addresses this neglected area of research and provides important information about the amount of time that older individuals invest in religious pursuits in organizational settings and how this varies across sociodemographic factors and denomination. Lastly, this analysis incorporates the impact of complex survey design effects. Adjusting for the effects of complex sample design has been routine in areas such as epidemiology, but has been rarely utilized in the field of religion and aging.

METHODS

Sample

The National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL) was collected by the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research. The field work for the study was completed by the Institute for Social Research’s Survey Research Center, in cooperation with the Program for Research on Black Americans. The NSAL sample has a national multi-stage probability design which consists of 64 primary sampling units (PSU’s). Fifty-six of these primary areas overlap substantially with existing Survey Research Center’s National Sample primary areas. The remaining eight primary areas were chosen from the South in order for the sample to represent African Americans in the proportion in which they are distributed nationally. The data collection was conducted from February 2001 to June 2003. The interviews were administered face-to-face and conducted within respondents’ homes; respondents were compensated for their time.

A total of 6,082 face-to-face interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older, including 3,570 African Americans, 891 non-Hispanic Whites, and 1,621 Blacks of Caribbean descent. There are 837 African Americans age 55 and over which is the sample used in this paper. The overall response rate of 72.3% is excellent given that African Americans (especially lower income African Americans) are more likely to reside in major urban areas which are more difficult and expensive with respect to survey fieldwork and data collection. Final response rates for the NSAL two-phase sample designs were computed using the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines (for Response Rate 3 samples) (AAPOR 2006) (see Jackson et al. 2004 for a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample). This study has been approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The present analysis investigates six measures of organizational religious participation. Ever attend religious services is measured by the question: “Other than for weddings or funerals, have you attended services at a church or other place of worship since you were 18 years old?”[Yes, No]. Frequency of religious service attendance is measured by combining the previous item with the question: “How often do you usually attend religious services? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or less than once a year?” The resulting categories for this variable are: nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, less than once a year and never attended since the age of 18 except for weddings and funerals. Number of hours at religious services on a typical Sunday/Saturday was measured by the question: “On a typical (Sunday/Saturday) how many hours are you at your church or place of worship?” Church membership is measured by the question “Are you an official member of a church or other place of worship?” [Yes, No]. Frequency of participation in church activities is measured by the question “Besides regular service, how often do you take part in other activities at your church? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or never?” Number of hours per week in other activities at the place of worship is measured by the question: Not including religious services, how many hours per week are you at your place of worship?

Demographic Description

The respondents in this older African American sub-sample ranged in age from 55 to 93 years (M = 66.62 and SD = 7.26). Approximately 60% of the respondents are women and, overall, four out of ten are married (39.71%), three out of ten are widowed (31.81%) and three out of ten respondents (28.47%) are divorced, separated or never married. More than half (55.6%) of the sample reside in the South. With regards to socio-economic status, the average imputed family income is $32,881 (SD = $33,110) and the average years of education is 11.48 (SD = 2.96). Respondents in the NSAL reported over 60 different religious denominations. One half of the respondents in this older African American sub-sample were Baptists (52.26%), 5.61% were Catholic, 9.12% were Methodists, 7.04% were Pentecostal, 1.70% were other religions (e.g., Muslims, Buddhist, Hindu, Jewish), 19.15% percent reported other Protestant groups and 5.11% did not indicate a current religious denomination.

Analysis Strategy

Means and percentages were calculated to provide the demographic description of the sample. The dependent variables are weighted based on the distribution of African Americans in the population. Six regression equations of the demographic correlates of organizational religious participation were calculated. Logistic regression was used to analyze the two dichotomous dependent variables (i.e., ever attended religious services since the age of 18, church membership). Linear regression was used to analyze frequency of service attendance and frequency of participation in congregational activities. Poisson and negative binomial regressions were used to model the two time use variables relating demographic factors to the number of hours spent at place of worship (given that these data reflect counts). In particular, univariate measures (i.e., means, variance, histogram) of typical hours spent at place of worship (Sunday/Saturday) revealed a Poisson distribution. For this dependent variable, the mean was approximately equal to the variance, satisfying the main assumption of Poisson regression. In contrast, the distribution of hours spent per week at one’s place of worship displayed overdispersion, as the variance exceeded the mean in this subsample of older African Americans. In this case, negative binomial regression, a generalization of the Poisson model, was more appropriate. This analysis strategy is consistent with recent research on time allocation (Rotolo and Wilson 2006). All regression analyses were conducted using STATA 9.2. The regression coefficients also incorporate the sample’s race adjusted weights and the standard errors reflect the recalculation of variance using the study’s complex design.

RESULTS

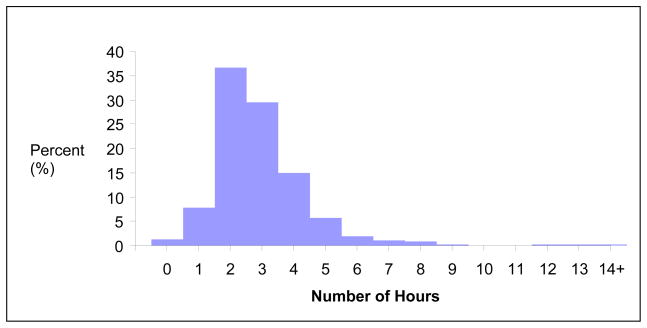

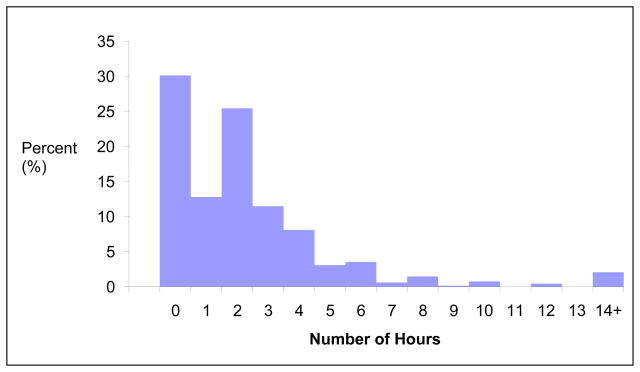

Only four percent of respondents indicated that they had not attended religious services since the age of 18. Half of the sample indicated attending religious services at least once a week whereas, 27.17% reported attending religious services a few times a year or less. Of the respondents who attended religious services at least a few times a year, 82.5% of them were official members of their place of worship. Additionally, for respondents who attended services at least a few times a year, 6% participated in other activities at their church nearly everyday, 22.8% at least once a week, 22.3% a few times a month, 24% a few times a year, and 24.7% never participate in other activities. Respondents who went to religious services at least a few times a year, spent an average of 2.9 hours (S.D. = 1.42) at their place of worship on a typical Sunday and averaged another 2.6 hours (S.D. = 4.087) at their place of worship during the week. Bar charts of the univariate distributions for the time usage variables are provided in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Number of hours at religious services on a typical Saturday or Sunday

Figure 2.

Number of hours per week in other activities at place of worship.

Table 1 presents the results of the regressions of the sociodemographic and denomination factors on organizational religious participation. Model 1 presents the logistic regression coefficients for ever having attended religious services since the age of 18. Divorced respondents were more likely than married respondents to indicate that they hadn’t attended services since the age of 18 (never married persons bordered significance). Regional differences indicated that respondents who resided in the Northeast were more likely to have never attended services as compared to Southerners. There were no denominational effects for never attending services. However, it is important to note that the categories Pentecostal and Other Religions were eliminated from the denomination variable for this analysis. All of the respondents in these two denomination categories reported that they had attended church since the age of 18 and, hence, there was no variation for these categories on the dependent variable.

Table 1.

Regression Analysis of the Correlates of Organizational Religious Participation among Older African Americansa

| Organizational Religious Participation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1b Ever attend religious services since 18 | Model 2 Frequency of religious service attendance | Model 3c Number of hours spent at religious services | Model 4b Church membership | Model 5 Frequency of participation in other activities | Model 6d Number of hours per week in other activities | |

| Age | 1.01 (,025) | .004 (.005) | –.000 (.002) | 1.01 (.019) | –.001 (.006) | .001 (.007) |

| Gendere: Female=1 | 1.72 (.920) | .478*** (.101) | .038 (.056) | 4.48 *** (1.46) | .315** (.114) | –.322* (.151) |

| Incomef | .953 (.025) | –.015 (.008) | –.000 (.005) | 1.00 (.020) | –.002 (.008) | –.010 (.013) |

| Education | 1.09 (.075) | .042 (.014)** | .000 (.009) | 1.04 (.040) | .026 (.014) | .036 (.022) |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Separated | .564 (.548) | –.427** (.144) | –.092 (.063) | .721 (.368) | –.419 (.238) | –.206 (.159) |

| Divorced | .221* (.156) | –.369* (.143) | –.039 (.045) | .776 (.255) | –.188 (.151) | .028 (.218) |

| Widowed | .621 (.507) | –.167 (.114) | –.058 (.061) | 1.60 (.700) | –.138 (.147) | .059 (.211) |

| Never married | .252 (.176) | –.256 (.177) | –.162* (.065) | .504 (.234) | –.279 (.212) | .717 (.439) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | .204*** (.084) | –.643*** (.171) | .054 (.027) | .550 (.206) | –.158 (.123) | –.153 (.190) |

| North Central | 1.08 (.690) | –.195 (.125) | –.040 (.036) | .436** (.119) | –.179 (.161) | .227 (.287) |

| West | .852 (1.19) | –.102 (.215) | .191* (.092) | .279 (.186) | .490** (.177) | .281 (.190) |

| Denomination | ||||||

| Methodist | .779 (.691) | .031 (.153) | –.241*** (.065) | .715 (.237) | –.092 (.168) | –.154 (.321) |

| Pentecostal | -- | .743*** (.107) | .361** (.119) | 2.96 (2.05) | .637** (.187) | .033 (.196) |

| Catholic | .779 (.525) | .210 (.243) | –.643*** (.080) | 6.15* (4.47) | .155 (.142) | –.310 (.280) |

| Other Protestant | 3.43 (3.79) | .399* (.157) | –.113* (.046) | 1.17 (.483) | .318 (.176) | –.413* (.156) |

| Other religion | -- | .157 (.393) | –.163 (.152) | .772 (.592) | –.419 (.274) | –.661* (.280) |

| No religion | .364 (.195) | –1.38*** (.163) | –.171 (.127) | .176* (.119) | –.473* (.206) | –1.58* (.722) |

| Constant | -- | 3.38*** (.416) | 1.17*** (.225) | -- | 2.23*** (.442) | .659 (.564) |

| F statistic | –3.23** | 19.16*** | 9.59*** | –4.13** | 6.60*** | 1.90 |

| R-squared | -- | 0.22 | -- | -- | .088 | -- |

| N | 815 | 815 | 708 | 711 | 711 | 525 |

Coefficients are unstandardized except for the logistic regressions where odds ratios are presented. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

Logistic regression (odds ratios are presented)

Poisson regression

Negative binomial regression

Several predictors are represented by dummy variables: Gender, 1=female; Marital status, married=0, Region, South=0, Denomination, Baptist=0.

Income is coded in dollars and has been divided by 5000 in order to increase effect sizes and provide a better understanding of the net impact of income.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

The results in Model 2 indicate that gender, education, marital status, region and denomination were significantly associated with frequency of attending religious services. Women attended services more frequently than men and married respondents attended services more frequently than both separated and divorced respondents. Persons with more years of formal education attended religious services more frequently than respondents with fewer years of formal education. Respondents who resided in the South attended services more frequently than those who resided in the Northeast. Several significant denomination differences indicate that respondents who report attending Pentecostal and other Protestant churches attend religious services more frequently than Baptists. Additionally, respondents who indicated that they did not have a current religious denomination indicated attending religious services less frequently than Baptists.

Model 3 presents the regression analysis of the number of hours spent at the respondent’s place of worship on a typical Sunday or Saturday (respondents who attended religious services less than once a year were not asked this question). Never married respondents indicated that they spent fewer hours at religious services than married respondents. Respondents who resided in the West indicated that they spent more hours in religious services than Southerners. Denominational differences indicated that Methodists, Catholics and respondents in other Protestant denominations spent fewer hours in religious services than did Baptists. Pentecostals, however, indicated that they spent more hours in religious services than Baptists.

Model 4 presents the logistic regression analysis of the probability of being an official member of a place of worship (respondents who attended religious services less than once a year were not asked this question). Gender, region and denomination were significantly associated with the likelihood of being an official member of a place of worship. Women had a greater likelihood than men and Southerners were more likely than respondents who resided in the North Central region to be official members of their place of worship. Among the denominational categories, Catholics had a higher likelihood of being an official church member than Baptists. As might be anticipated, those reporting no denomination were less likely than Baptists to be an official member of a place of worship.

The regression analysis for frequency of engaging in other congregational activities is presented in Model 5 (this question was not asked of respondents who attended religious services less than once a year). Gender, region and denomination were significantly associated with frequency of participating in congregational activities. Women indicated that they participated more frequently than men and respondents who resided in the West participated more frequently than Southerners. Additionally, Baptists participated in congregational activities less frequently than members of Pentecostal denominations, but more frequently than individuals who did not report a denomination. Finally, Model 6 presents the regression analysis for the number of hours per week (not including religious services) that respondents spent at their place of worship (respondents who attend religious services less than once a week and those who never take part in congregational activities at their place of worship were not asked this question). Gender and denomination were significantly associated with this dependent variable. Women indicated spending fewer hours per week at their place of worship than did men. Lastly, Baptists spent more hours per week at their place of worship than respondents who were in Other Protestant Denominations, Other Religions, and those who did not have a religious denomination.

DISCUSSION

This analysis examined the sociodemographic and denominational correlates of organizational religious participation among older African Americans. The study utilized data from a national probability sample and investigated a fairly extensive set of measures of organizational religiosity, including two measures of time allocation. The study findings reinforce previous work demonstrating relatively high levels of organizational religious behavior among older African Americans (Krause 2006; Levin et al. 1994; Taylor et al. 2004; Taylor et al. 2007). Several significant gender differences in organizational religious behavior were consistent with findings from previous research on both older African Americans and older Whites which indicates higher levels of religiosity of women (Krause 2006; Levin et al.1994; Taylor 1986; Taylor et al. 2004; Taylor et al. 2007). Namely, women attended religious services more frequently, were more likely to be church members and participated in congregational church activities more frequently than men. One unexpected finding indicated that men reported significantly more hours per week at their place of worship than did women. This is at odds with the finding that women are more engaged in their congregations (Winseman 2002) and participate in activities at their church more frequently than men.

One possible explanation for these disparate findings focuses on a consideration of what older African American men actually do in religious settings during a typical week. When reporting hours spent during a typical week, men may include a variety of volunteer work and activities such as cleaning, cutting grass, shoveling snow, opening and closing buildings, and minor repairs. This may be in addition to congregational activities in their church such as participating in the men’s club, choir, and bible study. For example, older men who are former construction workers may serve as supervisors during church construction or remodeling projects. Churches may be a primary social outlet and sphere of productive activity for older African American men, particularly those who are no longer active in the labor force. Many older black men who are involved in the church serve as deacons or stewards and may spend several hours a week in church related activities and business meetings. In their capacity as deacons/stewards, older Black men are often charged with supervising the church building on Saturdays and Sundays, often making them available for various activities taking place at the church (e.g., choir rehearsals, deacons’ meetings, Sunday services) and providing needed maintenance services. Deacons and stewards are also required to remain after church services to make an accounting of the collection(s) and secure the building after all church-related functions for any given day. Further, in the time period between morning and late afternoon services, they may make visits to the “sick and shut-in” and those in the hospital in order to provide communion and other forms of ministry. Women, on the other hand, may participate in structured congregational activities (e.g., study groups) more often, but spend less time in the unstructured activities (i.e., chores, talking with friends) at their place of worship.

It is important to note that the gender difference in hours spent in weekly church activities likely reflects a selection effect (please note that this analysis is on a subset of the sample: respondents who attend religious services less than once a week and those who never take part in congregational activities were not asked this question). Overall, there are fewer older men than women who regularly attend church and who are involved in formal church activities. However, those who are involved typically occupy leadership positions that require significant time commitments. Further, the importance and centrality of work in the lives of men is reflected in their church involvement in post-retirement. The church becomes the venue in which older African American men can retain, or perhaps even achieve, important “work” roles, status and prestige even if they are currently not employed. This may be particularly true of the growing number of “young” retirees who are able (or forced) to retire early (prior to age 65), who are skilled and are seeking opportunities to be involved in productive activities beyond formal employment. Older women may also participate in church activities for some of the leadership opportunities that are available. However, women’s participation may also be motivated by purely religious considerations, as well as the relational aspects of church involvement. In sum, older men reported lower rates of attendance, membership and formal congregational activities than did women, but spent more hours per week at the church than older women. This difference is likely due to older men’s involvement in time-intensive church leadership positions, as well as in ancillary roles and informal activities that are not reflected in assessments of formal church activities and groups.

Consistent with the gender differences in time spent in congregational activities, Krause (2006) found that older African American women attended bible study groups and prayer groups more frequently than older African American men. Further, although there were no significant gender differences in the frequency of completing jobs and tasks around the church (i.e., cooking and yard work), older African American men were much more likely to be in leadership positions (i.e., deacons, elders and lay ministers) within the church. These types of leadership positions required that men spend more time at the church during the week fulfilling various roles and responsibilities.

The predominance of men in leadership positions in Black churches can be attributed to two factors. Historically, within the broader society, African American men were unable to hold leadership positions in employment settings, civic organizations or as elected or appointed officials due to Jim Crow laws and workplace discrimination. Within the Black community, churches became the primary site for the development of resources to address the social welfare, civic, political, educational and health needs of African Americans. The black church was instrumental in developing human capital and in utilizing men in the congregation to fill the leadership roles and responsibilities associated with these church-based activities and initiatives. Further, due to the significant sex ratio disparities among African Americans of all age groups, but especially among the elderly, there have been long-standing concerns about the shortage of men in religious settings. In an attempt to address this problem, many pastors have made concerted efforts to invite men to participate in the church and to ensure that they stay actively involved by providing opportunities to develop leadership roles and responsibilities (Winesman 2002).

Marital status differences indicated that married respondents had significantly higher levels of involvement in organizational pursuits. In contrast, never married respondents participated in congregational activities less frequently, divorced respondents were less likely to have attended religious services since the age of 18, and both divorced and separated persons attended religious services less frequently than married persons overall. These findings are consistent with previous work indicating that married older adults have higher levels of organizational religious participation, as well as higher levels of nonorganizational and subjective religious involvement (Taylor et al. 2004).

The relationship between divorced status and the two attendance measures deserves special comment. As compared to married individuals, divorced persons were less likely to have attended church as an adult and overall attended religious services less frequently. A portion of the relationship between frequency of attendance and being divorced is attributable to the overall higher levels of religious participation among married adults. In addition, however, the stigma of divorce may function to diminish participation in religious settings, as it does in other informal support networks (Gertsel 1987), resulting in overall lower levels of attendance. Alternatively, the finding that divorced older persons were less likely than their married counterparts to have attended religious services since the age of 18, may suggest that involvement in religious settings may protect against divorce. That is to say, values and orientations embodied within religious settings are consistent with and actively promote sound marital relationships. Further, religious communities provide opportunities for both marital and family life counseling and skills training, as well as access to reference groups and individuals who model and reinforce shared values and behaviors relating to marital accord. Accordingly, older persons who have attended church since the age of 18 will have had the benefit of these experiences within religious settings and may be less vulnerable to marital problems and marital dissolution as compared to their counterparts who have not attended services as an adult. This interpretation is consistent with research indicating that religion provides a foundation for intimate relationships among African American couples (Carolan and Allen 1999) and, particularly for men, regular service attendance reduces the frequency of marital arguments and disputes (Curtis and Ellison 2002). Alternatively, given that religious involvement is normative for older cohorts of African Americans, persons who have not attended services as an adult likely represent an especially unique group that may differ with respect to other underlying personality or social factors that may be associated with marital instability.

Regional distinctions represent one of the more consistent demographic differences in religious participation among African Americans with Southerners demonstrating higher levels of religiosity (Chatters et al. 1999; Taylor et al. 2004). In the present analysis, respondents who resided in the Northeast (in comparison to Southerners) were more likely to have never attended religious services since the age of 18 and attended services less frequently overall. Southerners were also more likely to be church members than respondents who resided in the North Central region. The higher level of religiosity among Southerners is consistent with the view of the South as the Bible Belt and previous research documenting high levels of religiosity among African Americans in the South, particularly in rural areas (Ellison and Sherkat 1995; Taylor 1986; Taylor et al. 2004).

The current analysis, however, found two divergent findings indicating that respondents who resided in the West participated in congregational activities at their place of worship more frequently and spent more hours per week at their place of worship than did Southerners. These findings were unexpected and inconsistent with previous work on regional differences in religiosity. It is important to note, however, that research on participation in congregational activities is extremely limited. Further, the time allocation measures used in this study have not been previously examined in the literature. Future research exploring regional differences in congregational activities and time allocation among older African Americans may clarify these discrepancies. Qualitative research, involving intensive ethnographic studies and focus groups, may be particularly helpful in this regard. Recent focus group studies have been useful in understanding the role of religion and religious behaviors in the lives of both African American adults across the entire age range (Taylor et al. 2004) and among elderly African Americans (Krause, Chatters, Meltzer & Morgan 2000). Finally, only one significant education finding emerged for organizational religious participation indicating that older African Americans with more years of formal education attended religious services more frequently than persons with fewer years of education. Although it is commonly thought that poorer and adults with fewer years of education attend religious services more frequently, research on African Americans has shown that education is positively associated with attendance (Chatters et al. 1999; Taylor 1988).

Denomination differences were evident across several measures of religious participation. First, Catholics were more likely to be church members than Baptists. This is consistent with work indicating a high degree of structure and hierarchical organization within Catholicism and the importance of maintaining organizational structures. Thus, Catholic churches may have an explicit norm stressing the importance of becoming official members of the parish. This is in contrast to Baptist churches that are more independent in nature and structure. Second, Catholics spend fewer hours in services on a typical Sunday than Baptists. This is consistent with qualitative work on denominational differences in congregational climate and activities (Pargament et al. 1983). Third, in comparison to Baptists, Pentecostals attend religious services and participate in congregational activities more frequently and spend more hours at a place of worship on a typical Sunday. Recent findings from the Gallup Poll indicate that Pentecostals report higher levels of religious service attendance than Baptists and, overall, some of the highest levels of attendance of any denomination (Newport 2006). The findings of more frequent participation in congregational activities and more hours spent in church during the week are also consistent with other work on Pentecostal worship patterns. Although both Baptists and Pentecostals have high levels of church participation, prior research indicates that among Pentecostals, congregational activities (e.g. prayer groups, choir) play a particularly important role in daily life (Miller 2002).

In addition to the discussion of the demographic correlates, several other general observations concerning this analysis are warranted. First, very few factors were associated with never attending services since the age of 18 (divorced status and Northeast residency). This is likely due to the fact that this variable is somewhat skewed and reflects the generally high rates of religiosity of older African Americans. Second, the number of hours spent at services on a typical worship day varies more by denomination than by gender, socio-economic status or other demographic variables, suggesting that worship practices reflect normative patterns that vary by denominational affiliation. Third, the results of this analysis indicate that research on time allocated to religious pursuits is an important topic deserving of further study. This may be particularly true for research examining religion as a protective factor.

Research on time allocation in religious settings and the specific types of activities engaged in, may lead to a greater understanding of the mechanisms and pathways through which religion protects health. For example, among adolescents, greater amounts of time spent at one’s place of worship may expose adolescents to health-enhancing attitudes and behaviors and reduce opportunities to engage in deviant behaviors that may have health damaging consequences. In the case of older adults, significant time investments in religious settings provide opportunities for social contact and interaction, as well as involvement as both provider and recipient in social support networks in which various types of assistance is exchanged. Research examining the potential health protective effects of time allocation in religious settings should explore whether church activities embody potential biobehavioral (e.g., behavioral prescriptions promoting health lifestyles), psychosocial (e.g., access to and enhancement of personal and social resources), and psychodynamic (e.g., positive cognitive and affective strategies and states) mechanisms and pathways that impact health (Ellison and Levin 1998). In addition, it would be important to examine the potential negative health impacts of situations in which time investments in religious settings are especially onerous, accompanied by perceptions of burden, and characterized by the presence of negative social interactions.

Along these same lines, future research should employ diary methods and other more intensive strategies for investigating time use. These procedures would provide a better understanding of not only how much time individuals allocate to religious pursuits, but would also assess the quality and intrinsic character of those commitments, and how they may change over time and in response to varying circumstances. Finally, the present findings suggest that a more intensive focus on gender and denomination is needed in relation to studies of time allocated to religious pursuits. Such efforts would move beyond merely documenting these differences and would help us to develop a better understanding of how and why distinctive profiles of time commitments for women and men and within specific faith communities emerge and the benefits and costs that accrue to individuals from these investments.

In conclusion, the present analysis adds to the burgeoning literature on the importance of religion in the lives of older adults generally and, older African Americans, specifically. Basic studies addressing different types of religious participation provide important information on the rates and correlates of these behaviors and, further, lay the groundwork for other research that utilizes religious participation as an independent variable. The examination of religiosity is critically important in social gerontology given the documented high levels of religious involvement for older adults and its demonstrated association with health and well-being outcomes among this population. Research such as the present analysis will assist our understanding of this important feature of the lives of the vast majority of older Americans.

Acknowledgments

The data on which this study is based is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging to Drs. Chatters and Taylor (R01-AG18782) and Drs. Jackson and Taylor (P30-AG15281).

Biographies

Robert Joseph Taylor, Ph.D., M.S.W. is the Sheila Feld Professor of Social Work, Associate Dean for Research at the School of Social Work, and Associate Director of the Program for Research on Black Americans at the Institute for Social Research. He has published extensively on the informal support networks (i.e., family, church members) of Black Americans and has been Principal Investigator of several grants from the National Institute on Aging on the role of religion in the lives of Black and White elderly adults. Recent publications include: Religious Participation among Caribbean Blacks in the United States (with Chatters and Jackson).

Linda M. Chatters, Ph.D. is Professor of Health Behavior and Health Education at the School of Public Health and Professor in the School of Social Work, University of Michigan. Dr. Chatters’ research involves the study of aging as it relates to a variety of social contexts and the nature and functions of personal and social relationships on individual outcomes (i.e., social support, subjective well-being, and perceptions of health status). Recent publications include: Religious and Spiritual Involvement among Older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life (with Taylor and Jackson).

Kai McKeever Bullard, Ph.D. is currently a Health Research Analyst, Northrop Grumman Corporation, Atlanta Georgia. At the time she contributed to this project, Dr. Bullard was a Paul B. Cornely Postdoctoral Scholar with the Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture and Health, School of Public Health, University of Michigan. Dr. Bullard’s major research interests are racial/ethnic mental health disparities and comorbidity of mental and physical illness. Recent publications include Neighbors et al. (2007) Race, Ethnicity, and the Use of Services for Mental Disorders: Results from the National Survey of American Life and Ford et al. (2007) Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Disorders among Older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life.

John M. Wallace, Jr., Ph.D. is an associate professor of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh. His research examines the impact of religion as a protective factor against adolescent problem behavior; racial and ethnic disparities in substance abuse; and the role of faith-based organizations in the revitalization of urban communities. Dr. Wallace’s work has appeared in numerous professional journals, books and monographs including Social Work, American Journal of Public Health, and Social Problems. Recent publications include: The Influence of Race and Religion on Abstinence from Alcohol, Cigarettes and Marijuana Among Adolescents in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol.

James S. Jackson, Ph.D. is the Daniel Katz Professor of Psychology and Director of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. His research efforts include conducting national and international surveys of black populations focusing on racial and ethnic influences on life course development, attitude change, reciprocity, social support, physical and mental health and coping. Jackson is currently principal investigator of the National Survey of American Life and the Family Survey across Generations and Nations. Recent publications include: The National Survey of American Life: A Study of Racial, Ethnic and Cultural Influences on Mental Disorders and Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Robert Joseph Taylor, Email: rjtaylor@umich.edu, School of Social Work, University of Michigan

Linda M. Chatters, Email: chatters@umich.edu, School of Public Health and School of Social Work, University of Michigan

Kai McKeever Bullard, Email: hjo1@cdc.gov, Northrup Grumman Corporation, Atlanta, GA

John M. Wallace, Jr., Email: johnw@pitt.edu, School of Social Work, University of Pittsburgh

James S. Jackson, Email: jamessj@isr.umich.edu, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4. Lenexa, Kansas: AAPOR; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal. 1965;75:493–517. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma Gary D, Lennon Dan. Estimating the extent of religious and spiritual activity in Australia using time-budget data. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42(1):107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R Khari. Faith and works: Church-based social capital resources and African American political activism. Social Forces. 2003;82:617–641. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Khari R, McKenzie Brian D, Taylor Robert Joseph. A multiple sample comparison of church involvement and black political participation in 1980 and 1994. African American Research Perspectives. 2003;9:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carolan Marsha T, Allen Katherine R. Commitments and constraints to intimacy for African American couples at midlife. Journal of Family Issues. 1999;20:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters Linda M, Taylor Robert Joseph. Age differences in religious participation among black adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Science. 1989;44:S183–S189. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.5.s183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters Linda M, Taylor Robert Joseph, Lincoln Karen D. African American religious participation: a multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis Kristen Taylor, Ellison Christopher G. Religious heterogamy and marital conflict: Findings from the National Survey of Families and Households. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(4):551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison Christopher G, Levin Jeff S. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory and future directions. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:700–20. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison Christopher G, Sherkat Darren E. The ‘semi-involuntary institution’ revisited: Regional variations in church participation among black Americans. Social Forces. 1995;73:1415–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier Anne H, Smeeding Timothy M. Time use at older ages: Cross-national differences. Research on Aging. 2003;25(3):247–274. [Google Scholar]

- Gershuny Johathan, Sullivan Oriel. Time use, gender, and public policy regimes. Social Politics. 2003;10(2):205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsel N. Divorce and stigma. Social Problems. 1987;34(2):172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman Leo A. How to analyze survey data pertaining to the Time Bind, and how not to analyze such data. Social Science Quarterly. 2002;83(4):925–940. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth Sandra L, Sandberg John F. How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer Robert A, Ellison Christopher G, Rogers Richard G, Moulton Benjamin E, Romero Ron R. Religious involvement and adult mortality in the United States: Review and perspective. Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97(12):1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146547.03382.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson James S, Torres Myriam, Caldwell Cleopatra H, Neighbors Harold W, Nesse Randolph N, Taylor Robert Joseph, Trierweiler Steven J, Williams David R. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. The International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe Sean, Romer Daniel, Jamieson Patrick. Suicide acceptability is related to suicidal behavior among US adolescents. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(2):165–178. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster F Thomas, Stafford Frank P. The allocation of time: Empirical findings, behavioral models, and problems of measurement. Journal of Economic Literature. 1991;29:471–522. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Harold G, Larson David B, McCullough Michael E. Handbook of Religion and Health. NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal M. Exploring race and sex differences in church involvement during late life. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2006;16(2):127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal M, Chatters Linda M. Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion. 2005;66(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal M, Chatters Linda M, Meltzer Tina, Morgan David L. Using focus groups to explore the nature of prayer in late life. Journal of Aging Studies. 2000;14(2):191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeff S, Taylor Robert Joseph. Gender and age differences in religiosity in black Americans. The Gerontologist. 1993;33:16–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeff S, Taylor Robert Joseph, Chatters Linda M. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49(3):137–145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeff S, Taylor Robert Joseph, Chatters Linda M. A multidimensional measure of religious involvement for African Americans. The Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36:157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Mike. The meaning of community. Social Policy. 2002;32(4):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Newport Frank. Mormons, Evangelical Protestants, Baptists top church attendance list. Gallup Poll News Service. 2006 Date published: April 14, 2006. Date retrieved: September 13, 2007 ( http://poll.gallup.com/content/default.aspx?ci=22414&pg=1.

- Pargament Kenneth I, Silverman William, Johnson Steven, Echemendia Ruben, Snyder Susan. The psychosocial climate of religious congregations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:351–381. [Google Scholar]

- Alvin Poussaint, Alexander Amy. Lay My Burden Down: Unraveling Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis among African Americans. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Presser Stanley, Chaves Mark. Is religious service attendance declining? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2007;46:417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Presser S, Stinson L. Data collection mode and social desirability bias in self-reported religious attendance. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:137–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rotolo Thomas, Wilson John. Substitute or complement? Spousal influence on volunteering. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Robert Joseph. Religious participation among elderly Blacks. The Gerontologist. 1986;26(6):630–636. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Robert Joseph. Correlates of religious non-involvement among Black Americans. Review of Religious Research. 1988;29(4):126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Robert Joseph, Chatters Linda M, Jackson James S. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2007;62:S238–S250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Robert Joseph, Chatters Linda M, Levin Jeff S. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social, Psychological and Health Perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Robert Joseph, Thornton Michael C. Demographic and religious correlates of voting behavior. In: Jackson James S, Chatters Linda M, Taylor Robert Joseph., editors. Aging in Black America. Newbury Park, Ca: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, Gonzalez Hector M, Neighbors Harold W, Nesse Randolph N, Abelson Jamie M, Sweetman Julie A, Jackson James S. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the NSAL. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winseman Albert L. Religion and gender: A congregation divided, part II. 2002 Retrieved on September 5, 2007 ( www.galluppoll.com/content/?co=7390$pg=1)

- Wong Rebeca, Kitayama Kathy E, Soldo Beth J. Ethnic differences in time transfers from adult children to elderly parents: Unobserved heterogeneity across families? Research on Aging. 1999;21(2):144–175. [Google Scholar]