Abstract

Pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is required for fertility and is regulated by steroid feedback. Hyperpolarization-activated currents (Ih) play a critical role in many rhythmic neurons. We examined the contribution of Ih to the membrane and firing properties of GnRH neurons and the modulation of this current by steroid milieu. Whole-cell voltage- and current-clamp recordings were made of GFP-identified GnRH neurons in brain slices from male mice that were gonad-intact, castrated, or castrated and treated with estradiol implants. APV, CNQX, and bicuculline were included to block fast synaptic transmission. GnRH neurons (47%) expressed a hyperpolarization-activated current with pharmacological and biophysical characteristics of Ih. The Ih-specific blocker ZD7288 reduced hyperpolarization-induced sag and rebound potential, decreased GnRH neuron excitability and action potential firing, and hyperpolarized membrane potential in some cells. ZD7288 also altered the pattern of burst firing and reduced the slope of recovery from the after-hyperpolarization potential. Activation of Ih by hyperpolarization increased spike frequency, whereas inactivation of Ih by depolarization reduced spike frequency. Castration increased Ih compared with that in gonad-intact males. This effect was reversed by in vivo estradiol replacement. Together, these data indicate Ih provides an excitatory drive in GnRH neurons that contributes to action potential burst firing and that estradiol regulates Ih in these cells. As estradiol is the primary central negative feedback hormone on GnRH neuron firing in males, this provides insight into the mechanisms by which steroid hormones potentially alter the intrinsic properties of GnRH neurons to change their activity.

Introduction

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons form the final common pathway determining fertility in all vertebrate species. These neurons generate pulsatile hormone release that is frequency modulated by gonadal steroid feedback (Leipheimer et al., 1984; Levine et al., 1985a; Clarke et al., 1987; Levine and Duffy, 1988; Barrell et al., 1992). Changes in GnRH pulse frequency differentially regulate the synthesis and secretion of pituitary hormones in the target cells (Wildt et al., 1981; Shupnik, 1990). In brain slices and in culture, GnRH neurons are spontaneously active in an episodic manner (Terasawa, 1998; Kuehl-Kovarik et al., 2002; Moenter et al., 2003), but the mechanisms underlying intrinsic spike generation and episodic patterning are not well understood. One possibility is that this episodic release arises from an intrinsic pacemaker mechanism. GnRH neurons express a variety of intrinsic conductances that shape their firing patterns (Bosma, 1993; Kusano et al., 1995; DeFazio and Moenter, 2002; Kelly et al., 2002; Moenter et al., 2003; Chu and Moenter, 2006), some of which are known to be regulated by gonadal hormone feedback (DeFazio and Moenter, 2002; Chu and Moenter, 2006; Zhang et al., 2009).

The hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) is an inward current activated by hyperpolarization from typical neuronal resting membrane potentials (Crepel and Penit-Soria, 1986; McCormick and Pape, 1990; Erickson et al., 1993; Clarençon et al., 1996). Ih is crucial for regulating general membrane phenomena, including oscillatory activity and generating phasic burst firing in, for example, thalamic neurons (McCormick and Pape, 1990; Pape, 1996; Lüthi et al., 1998), hippocampal CA1 interneurons (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996), pyramidal neurons (Gasparini and DiFrancesco, 1997), and entorhinal cortical neurons (Nolan et al., 2007). Hyperpolarization-activated nonselective cation (HCN) channels conduct Ih (Robinson and Siegelbaum, 2003). In situ hybridization studies demonstrated that all four HCN channel subunits are expressed in the adult mouse and rat hypothalamus (Biel et al., 1999) as well as in immortalized GT1–7 GnRH neurons (Arroyo et al., 2006). A hyperpolarization-activated current was reported in GnRH neurons in brain slices (Zhang et al., 2007), but the pharmacology, contributions of this current to the firing properties of GnRH neurons, and the regulation of this current by steroid-hormone feedback have not been previously investigated. In the current study, we examined the function of Ih in changing intrinsic properties and firing pattern of GnRH neurons, and the regulation of these cells by gonadal hormone feedback.

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2006 Society for Neuroscience and 2009 Endocrine Society Meetings.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Adult (2–3 months of age) male mice expressing enhanced GFP (Clontech) under the control of the GnRH promoter were used to facilitate identification of GnRH neurons (Suter et al., 2000). A total 407 GFP-positive cells from 210 mice were used in these studies. Mice were maintained under a 14 h light:10 h dark photoperiod with Harlan 2916 chow (Harlan) and water available ad libitum. To study the influence of gonadal hormones, 184 mice were castrated (CAS) under isoflurane anesthesia (Burns Veterinary Supply) 5–9 d before experimentation; time after gonadectomy within this range did not affect results. The long-acting local anesthetic bupivacaine (0.25%; Abbott Labs) was applied locally to surgical sites to minimize postoperative pain and distress. The steroid hormone estradiol, which appears to be the main testosterone metabolite providing negative feedback on GnRH neuron activity in male mice (Pielecka and Moenter, 2006), was replaced in 29 of the 145 mice via SILASTIC (Dow Corning) implants containing 0.625 μg of estradiol dissolved in sesame oil. These implants were placed subcutaneously in the scapular region at the time of castration, eliminating the need for a second anesthesia. They produce low physiological levels of estradiol (DeFazio and Moenter, 2002; Christian et al., 2005). In addition, 36 gonadal intact mice were studied. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia approved all procedures.

Brain-slice preparation.

Brain slices were prepared as previously described (Nunemaker et al., 2003a; Chu and Moenter, 2005). All solutions were bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to maintain pH and oxygenation for at least 15 min before use and throughout experiments. In brief, brains were quickly removed and immersed immediately for 30–60 s in ice-cold sucrose buffer containing the following (in mm): 250 sucrose, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 10 glucose, 3.5 KCl, and 2.5 MgCl2. Sagittal brain slices (300 μm) through the preoptic area and hypothalamus were cut using either a Vibratome 1000 or 3000 (Technical Products International). Slices were immediately transferred into a holding chamber and incubated at 31–33°C for a 30 min recovery period in a mixture of 50% sucrose saline and 50% artificial CSF (ACSF) containing the following (in mm): 135 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1,25 Na2HPO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 10 d-glucose, 3.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, pH 7.4. Slices were then transferred to 100% ACSF and maintained at room temperature (∼21–23°C) until study (30 min to 8 h).

Data acquisition.

Slices were transferred to a recording chamber mounted on the stage of an upright microscope (BX50WI, Olympus) and stabilized in the chamber at least 5 min before recording. The chamber was continuously perfused with ACSF at a rate of 4–5 ml/min at 31–32°C. Pipettes (3–4 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (outer diameter, 1.65 mm; inner diameter,1.12 mm; World Precision Instruments) using a Flaming/Brown P-97 (Sutter Instruments). GnRH-GFP neurons from the preoptic area and ventral hypothalamus were identified by brief illumination at 470 nm. Data were acquired using an EPC-8 (HEKA Electronics) with an ITC-18 interface (Instrutech) controlled by the PulseControl XOP (Instrutech) running in IgorPro (Watermetrics) or using one headstage of an EPC-10 dual amplifier controlled by PatchMaster (both from HEKA Electronics). There were no differences attributable to the acquisition system. Signals were low-pass filtered at 10 kHz. During whole-cell recordings, input resistance (Rin), series resistance (Rs), and membrane capacitance (Cm) were continually measured from averaged membrane response to 5 mV hyperpolarizing voltage steps. Only recordings with stable Rin >500 MΩ and Rs <20 MΩ and stable Cm were used for analysis. Fast transients recorded after formation of the gigaohm seal in the cell-attached configuration were subtracted from the membrane response in the whole-cell configuration to correct for incomplete compensation of electrode capacitance. Data were further examined to make sure changes in Rin or Rs within acceptable limits did not influence results. Calculated liquid junction potential error, estimated to be −13 mV, was not corrected (Barry, 1994).

In all experiments, fast synaptic transmission to GnRH neurons was blocked by antagonists to ionotropic transmitter receptors (GABAA, 20 μm bicuculline methobromide; AMPA, 20 μm CNQX; NMDA, 20 μm APV). To characterize biophysical properties of Ih, tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) were used to block Na+ current and A-type current (IA), respectively, in voltage-clamp experiments. Nickel (100 μm) was used to block low-voltage-activated (LVA) calcium channels.

Voltage-clamp recordings.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp was used to study current activated by membrane hyperpolarization. Patch electrodes for voltage-clamp contained the following (in mm): 125 K gluconate, 20 KCl, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 4.0 MgATP, 0.4 NaGTP, 0.1 CaCl2, pH 7.3, 290 mOsm. Membrane potential was held at −50 mV. Current response to hyperpolarizing voltage steps (1–1.2 s duration, 10 mV interval) was evaluated. The protocol was repeated three times and traces were averaged for analysis. Additionally, a slow (1 mV/50 ms) ramp protocol from −50 to −130 mV was used to characterize Ih. Reversal potential of Ih was estimated using a protocol in which membrane potential was held at −50 mV, then stepped to −120 mV for 1 s, following which tail currents were measured at −70 mV to −120 mV (−10 mV interval, 1 s duration). The amplitude of the evoked current was measured from instantaneous and steady-state voltage response to prestep baseline level. Subtraction of traces before and after treatment with ZD7288 (ZD) was used to quantify ZD7288-sensitive current and thus identify Ih. Ion substitution was made as follows: to increase extracellular K+, KCl was substituted for NaCl in the ACSF; to reduce extracellular Na+, tetraethylammonium chloride was substituted for NaCl.

Current-clamp recordings.

Whole-cell current clamp was used to study membrane potential changes using the same pipette solution as in voltage-clamp studies. Current-clamp recordings were made using bridge balance and capacitance compensation, using the same pipette solution as above. All cells had an initial membrane potential negative to −55 mV without current injection and action potential amplitude of >90 mV. Direct current injection (<±10 pA) was used to normalize membrane potential to facilitate comparison during firing frequency studies. To study the voltage change induced by activating Ih, current injections (1–1.2 s, 0–−80 pA, −10 pA intervals) were given. In some cells, action potential firing rate was monitored; changes in firing rate of at least 20% were used to classify cells as responding to treatment.

To examine the effects of the Ih blocker ZD7288 on GnRH neuronal excitability, positive current injections (600 ms, 0–50 pA) were applied, and the number of spikes before and after treatment quantified. Sag and rebound potential amplitudes were measured from the precurrent injection membrane potential. Latency was the time from end of the current injection to the peak of the rebound depolarization potential. Depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current pulses (1–2 s) were used for activating and deactivating Ih; their effects on subsequent spontaneous action potential firing were determined by comparing spike frequency before current injection to that during the 3 s following termination of the current injection. The input resistance of GnRH neurons was determined from the steady-state voltage response to a hyperpolarizing pulse (10–15 pA producing ∼10 mV change in membrane potential). Series of action potentials (2–6 spikes) were considered to be components of a single burst when there was a steady depolarization from the peak of the after-hyperpolarizing potential to the initiation of the subsequent spike, and when they were separated by no more than 250 ms. The latter criterion was based on the duration of the slow after-depolarizing potential in GnRH neurons, which peaks ∼200 ms after spike initiation (Chu and Moenter, 2006). Single spikes and spikes per burst before and after ZD7288 were manually determined. To determine whether Ih participates in subthreshold depolarization of GnRH neurons, the slope from the peak of the after-hyperpolarizing potential of single spikes or the first spike of a two-spike burst to 200 ms thereafter was determined before and during treatment with ZD7288. To determine whether Ih alters slow after-depolarizing potential (sADP) following evoked action potentials, brief higher amplitude current injections were delivered (200–300 pA, 3 ms).

Drug treatments.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise noted. All treatments were bath-applied. The specific antagonist 4-(N-ethyl-N-phenylamino)-1,2-dimethyl-6-(methylamino) pyrimidinium chloride (ZD7288, 50 μm; Tocris Bioscience) was used to identify Ih in all experiments. To characterize biophysical properties of Ih, sodium channels were blocked with TTX (0.5 μm, Calbiochem) and dominant IA was blocked with 4-AP (3–5 mm; Tocris Bioscience). Response of hyperpolarization-activated currents to cAMP (100 μm), an important signal carrier for biological response of neurons to activation of some metabotropic receptors, and forskolin (10 nm), a compound to increase the intracellular cAMP concentrations, was also characterized, as was inhibition by 1 mm Ba2+ (a nonspecific blocker of inward rectifier potassium channels, BaCl2) and 3 mm extracellular Cs+ (which blocks Ih among other conductances and transporters, CsCl; Fluka). To distinguish between Ih and LVA calcium currents, Ni2+ was applied first to block LVA followed by subsequent treatment with Ni2+ and ZD7288 to block LVA and Ih.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using Instat or Prism (Graphpad Software). Data values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each cell served as its own control except in comparisons among animal models. Statistical comparisons were made using paired two-tailed Student's t test for comparisons within cells, or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. Significance was set at p < 0.05; all nonsignificant p values were >0.1, unless otherwise specified.

Results

GnRH neurons exhibit hyperpolarization-activated currents (Ih)

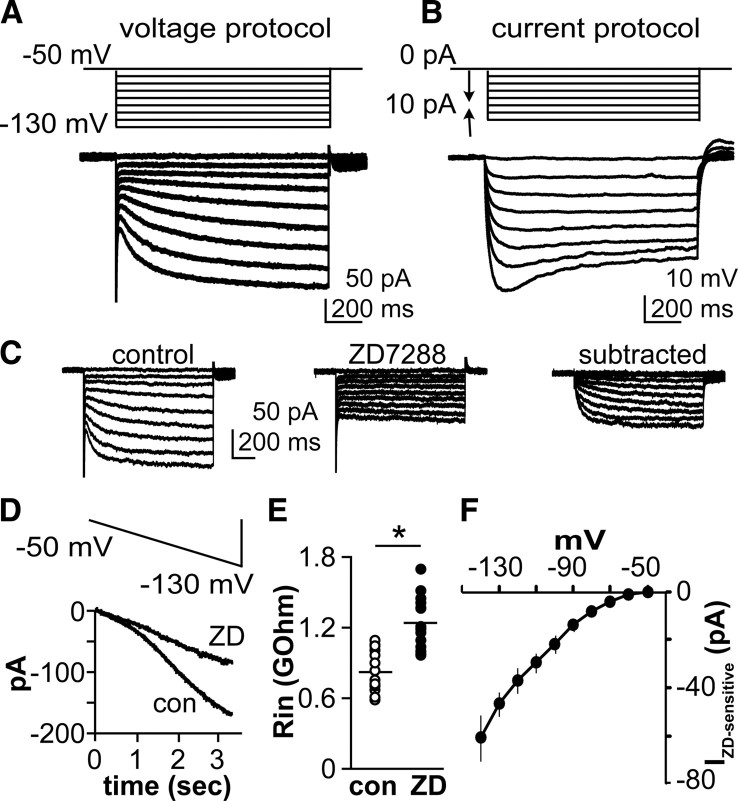

To examine hyperpolarization-activated currents in GnRH neurons, whole-cell recordings were made from GFP-positive neurons in brain slices from castrated male mice. Cells were isolated from the influence of fast synaptic transmission by blocking ionotropic GABA and glutamate receptors and fast sodium and A-type potassium conductances. As the membrane was stepped from a holding potential of −50 mV to more hyperpolarized potentials in 10 mV increments, an inward current was activated beginning between −60 and −70 mV (Fig. 1A). The current activated and inactivated slowly and was observed in 47% of recorded cells (193 of 407). There was no difference in initial resting potential between cells exhibiting Ih and those not exhibiting Ih (61.4 ± 1.1 mV with Ih, n = 16; 62.2 ± 1.1 mV without Ih, n = 18; p > 0.05). In current clamp, injection of hyperpolarizing current produced an initial membrane hyperpolarization followed by a return toward resting potential, or sag, with larger current injections (Fig. 1B). To test whether this hyperpolarization-activated current was conducted through HCN channels, the specific blocker ZD7288 (50 μm) was applied in voltage-clamp experiments. ZD7288 reduced the inward current within 5–8 min (Fig. 1C,F). When membrane potential was slowly (1 mV/50 ms) ramped from −50 to −130 mV, an inward current also developed over time and was reduced by ZD7288 (Fig. 1D). ZD7288 also increased input resistance of cells at membrane potentials near −80 mV (850.6 ± 44.9 MΩ in control vs 1248.0 ± 52.8 MΩ in ZD7288, n = 16, p < 0.01), indicating a reduction in membrane conductance (Fig. 1E) and reduced slope conductance from 1.19 ± 0.12 to 0.50 ± 0.03 nS (p < 0.05). Input resistance decreased with membrane hyperpolarization from −70 to −90 mV (949 ± 38 MΩ vs 700 ± 27 MΩ, n = 12, p < 0.01), suggesting opening of voltage-gated channels.

Figure 1.

A subpopulation of GnRH neurons exhibit a hyperpolarization-activated current. A, Top, voltage protocol; bottom, representative voltage-clamp recording showing current response with slowly developing inward current. B, Top, current injection protocol; bottom, representative current-clamp recording showing membrane response including voltage-dependent sag. C, Effect of ZD7288 on inward current generated by hyperpolarizing membrane potential steps. D, A ZD-sensitive current is also revealed by a slow hyperpolarizing voltage ramp. E, Effect of ZD7288 on input resistance (n = 12, p < 0.01). F, I–V relationship of ZD-sensitive current (n = 16, *p < 0.01). con, Control.

Pharmacological properties of hyperpolarization-activated currents in GnRH neurons

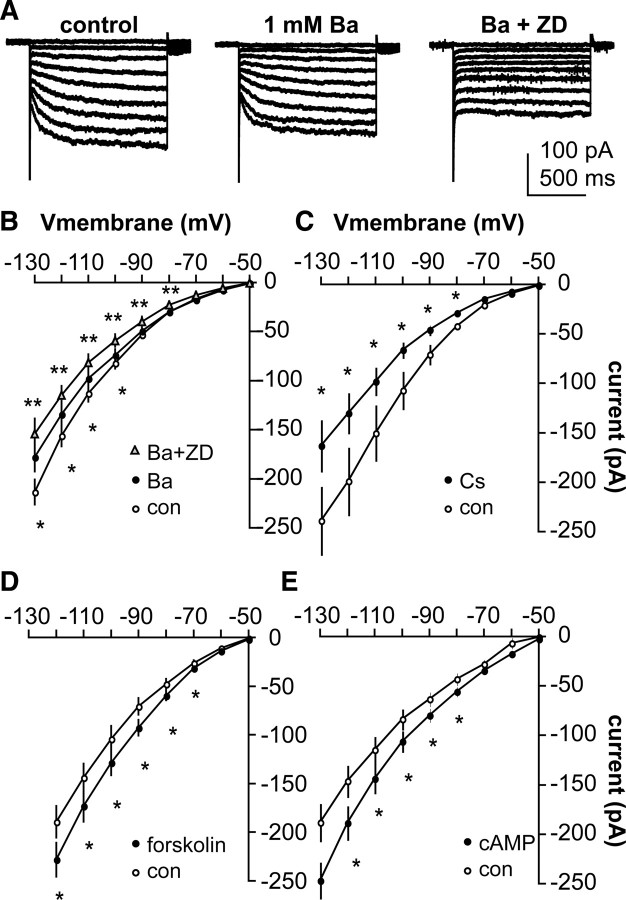

In addition to HCN channels, inwardly rectifying potassium channels (IKir) can be activated by hyperpolarization. The potassium channel blocker Ba2+ (1 mm) was able to block a component of hyperpolarization-activated current (n = 9, p < 0.05 vs control) (Fig. 2A,B). However, in most of these cells, ZD7288 was able to further reduce hyperpolarization-activated current (p < 0.05 vs Ba2+ alone) (Fig. 2A,B). Extracellular Cs+ (3 mm CsCl) also reduced the hyperpolarization-activated current (Fig. 2C) (n = 6, p < 0.01); although Cs+ can also block potassium channels, it has been reported as a blocker of HCN-mediated currents (Halliwell and Adams, 1982; Crepel and Penit-Soria, 1986; Spain et al., 1987; McCormick and Pape, 1990; Bayliss et al., 1994; Pape, 1996). The voltage dependence of HCN channel gating is strongly modified by hormones, neurotransmitters, and second messengers, making these channels exquisitely sensitive to changes in cellular environment (Pape and McCormick, 1989; Ludwig et al., 1998; Biel et al., 1999). The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Fig. 2D) (10 μm, n = 9, p < 0.01) and the second messenger cAMP (100 μm) increased the hyperpolarization-activated inward current in GnRH neurons (Fig. 2E) (n = 7, p < 0.01). Together, these pharmacological and biophysical properties suggest the hyperpolarization-activated current in GnRH neurons is mediated by HCN channels and is Ih.

Figure 2.

Pharmacological profile of the hyperpolarization-activated current in GnRH neurons indicates it is Ih. A, Representative voltage-clamp recordings showing control (left), treatment with 1 mm Ba2+ (center), and Ba2+ plus 50 μm ZD7288 (right). B–E, Changes in I–V relationship for 1 mm Ba2+ plus 50 μm ZD7288 (B, n = 9), 3 mm Cs+ (C, n = 6), 10 μm forskolin (D, n = 9), and 100 μm cAMP (E, n = 7). *p < 0.05 versus control (con), **p < 0.05 versus Ba.

Ion exchange and reversal potential estimation

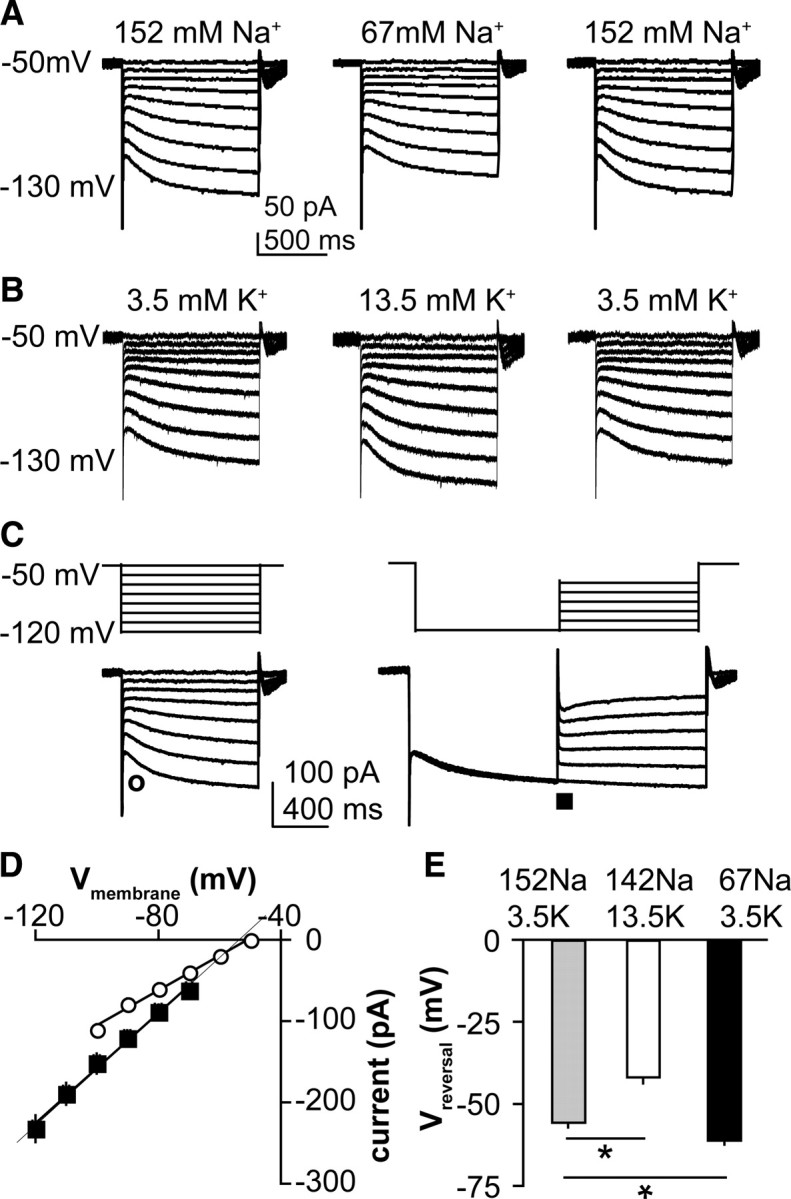

HCN channels pass both Na+ and K+ ions (Mayer and Westbrook, 1983; Crepel and Penit-Soria, 1986; Spain et al., 1987; McCormick and Pape, 1990). In ion exchange experiments, membrane current was reversibly reduced by a reduction in extracellular Na+ concentration (from 152 to 67 mm; 238.6 ± 22.9 pA to189.0 ± 19.3 pA, n = 6, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3A) and was increased by an increase in extracellular K+ concentration (from 3.5 mm to 13.5 mm; 226.3 ± 17.3 pA to 274.4 ± 13.1 pA, n = 5, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3B) when measured at a membrane potential of −120 mV. The reversal potential was determined using a protocol described by Bayliss (Bayliss et al., 1994; Funahashi et al., 2003). Instantaneous currents were measured immediately following the capacitive transient (Fig. 3C, open circle) after stepping from a potential at which Ih is not activated (−50 mV). In the same cell, Ih was activated by a 1 s prepulse at −120 mV, then the tail current was measured at the onset of test steps to potentials from −120 mV to −70 mV (10 mV increments) (Fig. 3C, right). Both resulting I–V plots were fit with linear regression and the reversal potential calculated from the point of crossover (n = 11) (Fig. 3D). The calculated reversal potential was similar to previously reported values in neurons (Spain et al., 1987; Schlichter et al., 1991), and was sensitive to changes in concentration of either Na+ or K+ ions in the extracellular solution (both manipulations, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

The hyperpolarization-activated current in GnRH neurons is carried by both Na+ and K+ ions. A, B, Representative voltage-clamp recordings showing current changes in response to reduction of extracellular Na+ (A, n = 6) or increase in extracellular K+ (B, n = 5). C, Top, Protocols used to establish reversal potential; bottom, representative voltage-clamp recording showing time of measurement of instantaneous current (○, left) and tail current (■, right). D, Calculation of reversal potential by linear fit of average voltages from C (n = 11). E, Effect of ionic manipulations on reversal potential (Vreversal). *p < 0.05.

Blocking Ih decreases GnRH neuronal excitability and action potential firing

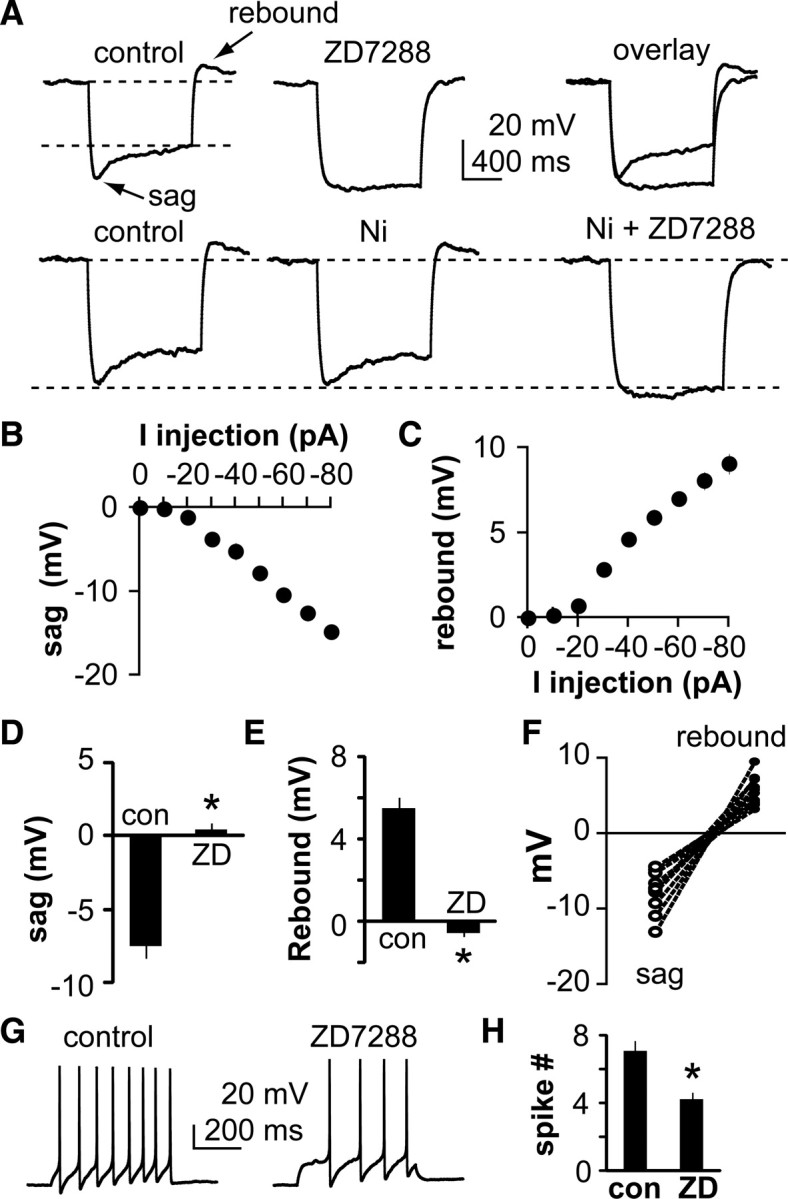

To examine the action of Ih in GnRH neuronal function, whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made. Injection of hyperpolarizing current pulses (10–80 pA, 600 ms) elicited a hyperpolarization during which a depolarizing sag developed over 800 ms, a time course consistent with the slow kinetics of Ih, allowing this depolarization to be distinguished from that which might be caused by a T-type calcium current (Sun et al., 2010). After termination of a hyperpolarizing current injection (−50 pA), a prominent rebound depolarization potential was observed (Fig. 4A, top). Nickel (100 μm) did not block the rebound (control, 4.8 ± 0.5 mV; Ni2+, 4.3 ± 0.4 mV; n = 8) (Fig. 4, bottom). Both sag and rebound potentials increased with increasing hyperpolarizing current injection (Fig. 4B,C), and were reduced by ZD7288 (n = 11, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4A,D,E). Further, there was a direct association between amplitude of the sag and that of the rebound potential, suggesting a common mechanism (Fig. 4F). Finally, blocking Ih with ZD7288 decreased GnRH neuron excitability upon injection of a 20 pA, 600 ms depolarizing current pulse response to depolarizing current injection (p < 0.01, n = 14) (Fig. 4G,H).

Figure 4.

Blocking Ih alters membrane properties of GnRH neurons. A, Top, Representative current-clamp recordings showing the effect of a −50 pA current injection on GnRH neuron membrane potential. A characteristic sag develops during the injection and there is a rebound in membrane potential after termination of the current injection. ZD7288 blocks both the sag and rebound potentials. Bottom, Nickel fails to block the rebound, which is subsequently blocked by ZD7288. B, C, Voltage dependence of sag (B) and rebound (C) potentials in GnRH neurons (n = 11). D, E, Quantification of sag (D) and rebound (E) potentials before and during treatment with ZD7288 (n = 11). F, Relationship between sag and rebound potential in all cells studied. G, Response of GnRH neuron to 20 pA current injection under control (left) and ZD7288 (right) conditions showing that blocking Ih reduces excitability. H, Mean ± SEM spikes induced by a 40 pA current injection (n = 14, *p < 0.01). con, Control.

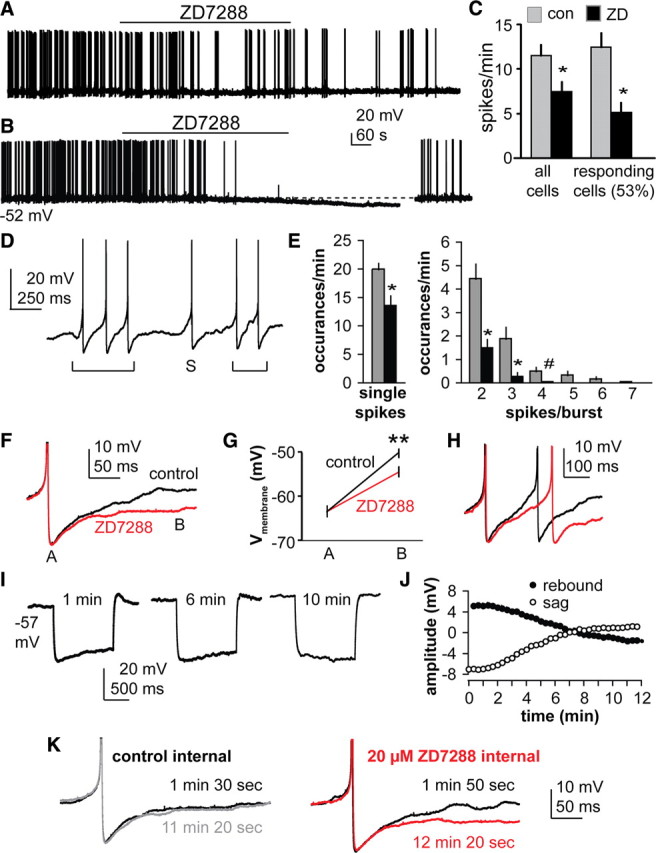

In recordings of spontaneous action potential firing in the presence of APV, CNQX, and picrotoxin to block ionotropic receptors for GABA and glutamate, blocking Ih decreased action potential frequency in ∼50% of cells, which is similar to the percentage exhibiting Ih in voltage-clamp studies (n = 9, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5). Visible membrane hyperpolarization was observed in 24% of cells (4 of 17 cells, −6.1 ± 0.5 mV). In the presence of TTX to block action potential firing, frank hyperpolarization was observed in 5 of 16 cells (4.8 ± 0.5 mV) with the remaining 11 being within 1 mV of the initial membrane potential (data not shown). ZD7288 reduced the overall action potential firing of GnRH neurons (11.5 ± 1.3 spikes/min in control vs 7.5 ± 1.2 spikes/min in ZD, n = 17, p < 0.01). For those cells that responded to ZD7288 with a reduction in overall firing rate, further analysis of single spikes and bursts was conducted (Fig. 5D,E). Blocking Ih altered the pattern of burst firing, reducing both single spikes and the number of spikes per burst (p < 0.01 for single spikes, two and three spike bursts, p < 0.05 for four spike bursts; statistics not performed on five, six, or seven spike bursts as these were not observed after ZD7288 treatment).

Figure 5.

Blocking Ih reduces the spontaneous firing rate of GnRH neurons. A, B, Effect of ZD7288 on firing activity of GnRH neurons. Membrane potential under the trace indicates potential at onset of trace. B, Some cells exhibited frank hyperpolarization in addition to a reduction in firing activity. A 10 pA current injection shown at the end of the trace in B illustrates the cell is still capable of generating action potentials. C, Firing rate before (gray bars) and during (black bars) ZD7288 treatment in all GnRH neurons (left, n = 17) and in only responding GnRH neurons (right, n = 9). D, Examples of single spike and burst firing; brackets below trace indicate bursts. S, Single spike. E, Blocking Ih reduces both single spikes and the number of spikes/burst. *p < 0.01, #p < 0.05. F, Representative example of the effect of ZD7288 (red) on the slope of the recovery from the AHP following single spikes (n = 16). **p < 0.001. G, Mean ± SEM membrane potential at points A (AHP amplitude) and B (200 ms post AHP peak) in F (n = 10). H, Example of interspike membrane potential dynamics in a two-spike burst; red trace is after ZD7288. I, Representative current-clamp recordings with ZD7288 included in the pipette solution showing response to a 50 pA hyperpolarizing current injection; rebound and sag disappear over time. J, Mean ± SEM amplitude of sag and rebound over time with ZD7288 in the pipette. K, Representative recordings illustrating action potential waveform at times indicated with control internal (left) and ZD7288 internal (right).

Blocking Ih also reduced the slope of the recovery from the after-hyperpolarization potential (AHP). For single spikes, there was no difference in the absolute peak value of the AHP (control, −63.5 ± 1.3 mV; ZD, −63.4 ± 1.4 mV, n = 10), but 200 ms after the peak of the AHP, control neurons had depolarized more (control, −50.2 ± 1.0 mV; ZD, −54.5 ± 1.1 mV, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5F,G). Within two spike bursts, a similar phenomenon was observed; ZD7288 delayed initiation of the second spike (Fig. 5H). Previous work indicated sADPs following evoked action potentials were not different in the presence or absence of ZD7288 in GnRH neurons from female mice (Chu and Moenter, 2006). To determine whether this is a sex difference or a methodological difference, we examined sADPs following evoked action potentials (200–300 pA, 3 ms) in male mice. Similar to findings in females, the sADP following evoked action potentials (two spikes, 50 ms interval) was not affected by blockade of Ih with ZD7288 (control, 3.8 ± 0.1 mV; ZD7288, 3.7 ± 0.2 mV; n = 14; p < 0.05). This indicates the spontaneous action potential/AHP waveform is more effective at activating Ih than the evoked waveform. Together, these data suggest Ih plays a role in the pattern of GnRH neuron firing as well as the subthreshold depolarization of these neurons to action potential threshold.

Although fast synaptic transmission via ionotropic GABA and glutamate receptors are blocked in these studies, we cannot rule out the role of neuromodulation in the effects of Ih on action potential waveform. To limit the range of the blocker to the GnRH neuron itself, we made recordings with ZD7288 in the pipette solution, as this blocker has an intracellular site of action (Shin et al., 2001). A 50 pA hyperpolarizing current pulse was given every 20 s and membrane response monitored over time. Intracellular ZD7288 (20 μm) was able to block sag and rebound beginning ∼2 min after initiation of the whole-cell configuration, reaching a plateau at ∼10 min (n = 7 cells selected for exhibiting evidence of sag in initial recordings) (Fig. 5I,J); recordings without ZD7288 within the pipette were stable over this time (recordings with Ni2+ at 8–10 min after achieving whole-cell configuration) (Fig. 4A, bottom). Examination of action potential waveform within the first 2 min of recordings of spontaneous firing with ZD7288 within the pipette before the drug became effective compared with after blockade of Ih revealed no change in waveform over time with control internal solution, but a similar suppression of rate of repolarization after the AHP when ZD7288 was in the internal solution (Fig. 5K). These data suggest that Ih directly within GnRH neurons contributes to altering the membrane properties.

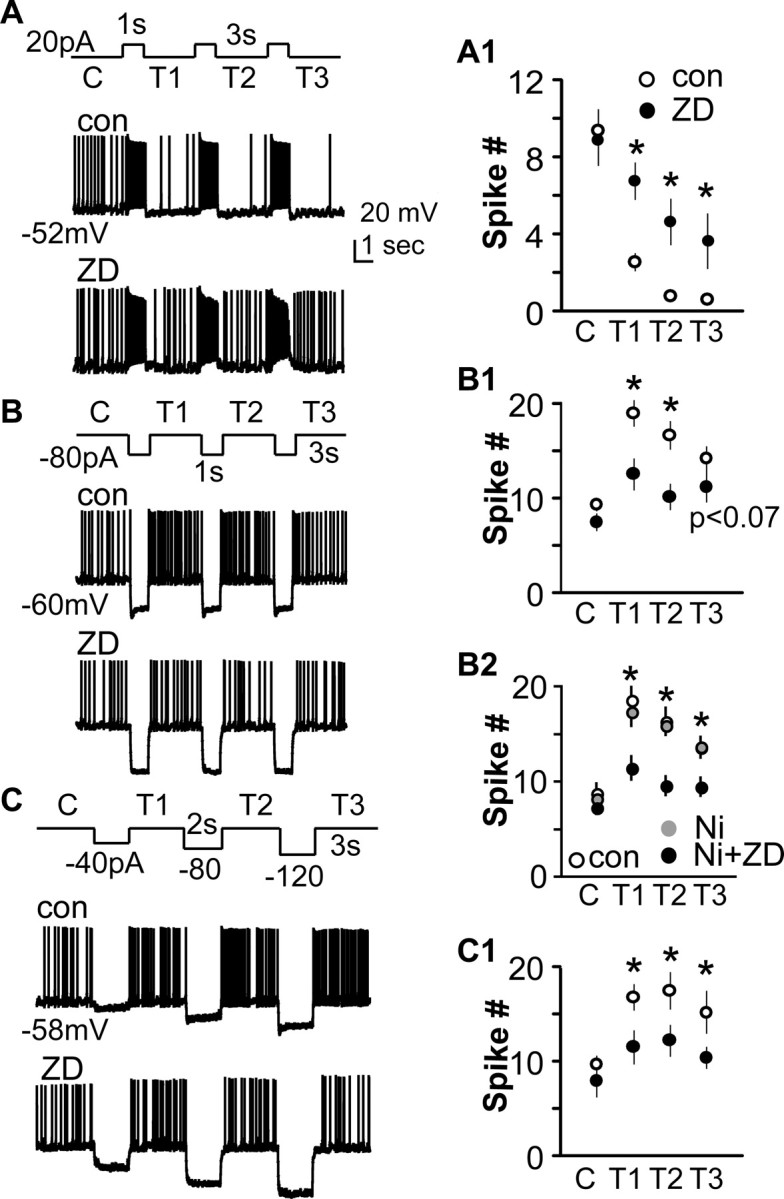

Activation of Ih by hyperpolarization increases GnRH firing

To further demonstrate the functional properties of Ih in GnRH neurons, whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made. Depolarizing current (20 pA, 1 s) was injected to deactivate Ih by membrane depolarization. These current injections increased firing rate in these GnRH neurons for the duration of injection, with little evidence of spike frequency adaptation (Fig. 6A,A1). Upon termination of the current injection, firing rate fell below preinjection values (n = 16, p < 0.01). This suppression was attenuated by ZD7288 (p < 0.01). Hyperpolarizing current injections were given to activate Ih. Depolarizing sag during current injection ranged from −7.8 to −15.3 mV. Upon termination of these injections, spike frequency was increased (Fig. 6B,B1) (n = 20, p < 0.05) in a ZD-sensitive manner. Treatment with Ni2+ to block T-channel-mediated rebound firing had no effect on rebound spike frequency, in contrast to the effect of the Ih blocker ZD7288 (n = 9 for control, Ni2+; n = 7 for Ni2+ plus ZD) (Fig. 6B2). Increasing the magnitude of hyperpolarization within the physiological range also produced a voltage-dependent increase in both depolarizing sag and rebound spike frequency (Fig. 6C) (n = 17, p < 0.05). These data suggest Ih within GnRH neurons contributes directly to altering membrane properties.

Figure 6.

Manipulation of Ih by changes in membrane potential alters firing properties of GnRH neurons. A–C, Membrane potential under the trace indicates potential at onset of trace. A, Current injection protocol. B, Membrane response under control (con) conditions. C, Membrane response during ZD7288 treatment. A1–C1, Quantification. A, Deactivating Ih by membrane depolarization reduces spontaneous firing in GnRH neurons in a ZD-dependent manner (n = 16). B, C, Activating Ih by membrane hyperpolarization increases spike frequency (n = 20 and 17, respectively). A1–C1, Mean ± SEM spike number for A–C. B2, n = 9 control and Ni; n = 7 Ni plus ZD. *p < 0.05. C, Control; con, control; T, trial (1, 2, or 3).

Gonadal steroid modulation of Ih currents in GnRH neurons

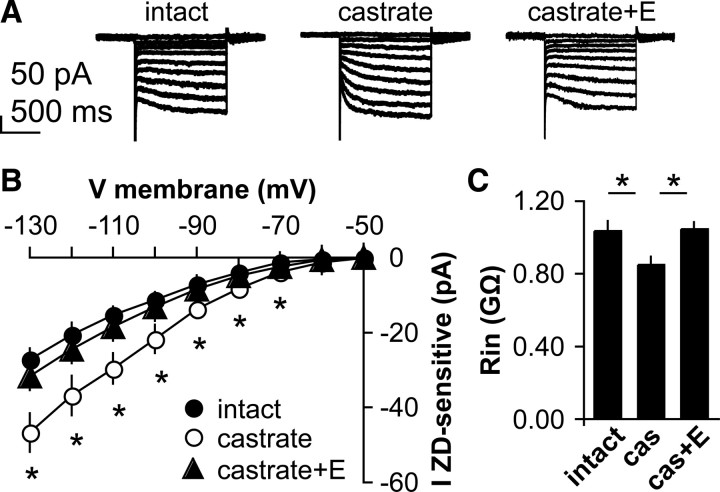

Gonadal steroids provide critical homeostatic feedback to regulate GnRH neurons that involve both changes in synaptic transmission to GnRH neurons and altered intrinsic excitability (DeFazio and Moenter, 2002; Nunemaker et al., 2002; Abe and Terasawa, 2005; Chu and Moenter, 2006; Wintermantel et al., 2006; Christian and Moenter, 2007; Romanò et al., 2008; Chen and Moenter, 2009; Chu et al., 2009). The involvement of Ih in increasing firing activity and excitability of GnRH neurons led us to hypothesize that this current is regulated by steroid feedback. To test this, voltage-clamp experiments were used to characterize the ZD7288-sensitive current in GnRH neurons from mice in different steroid feedback conditions. There was no difference in initial resting potential among cells from the different groups [intact, −61.4 ± 1.1 mV, n = 11; castrated, −59.8 ± 0.8 mV, n = 16; castrated plus estradiol (E), −60.3 ± 1.0 mV n = 12; p > 0.05]. Castration, which increases GnRH neuron firing activity (Pielecka and Moenter, 2006), increased the amplitude of Ih in GnRH neurons compared with that observed in gonad-intact males (n = 11 and 16, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 7A,B). Estradiol, a metabolite of testosterone, is the main hormone providing negative feedback upon GnRH neuron firing rate in male mice (Pielecka and Moenter, 2006). In castrate mice treated with estradiol (CAS+E), Ih is restored to intact values (n = 12, p < 0.05 vs castrate). Further, castration and steroid replacement alter input resistance of GnRH neurons in a manner consistent with increased conductance in castrated animals relative to the other two conditions (Fig. 7C). Likewise, the slope conductance of Ih in cells from castrated mice was increased (p < 0.001) compared with that from both intact and CAS+E mice (intact, −0.34 ± 0.03; CAS, −.60 ± 0.05; CAS+E, −0.40 ± 0.04 pA/mV). Together, these data suggest that steroid-sensitive changes in Ih may contribute to changes in firing of GnRH neurons in different feedback states.

Figure 7.

Ih is regulated by steroid milieu. A, Representative voltage-clamp recordings showing hyperpolarization-activated current in GnRH neurons from gonad-intact (left), castrate (middle), and castrate plus estradiol (right) groups. B, I–V curve of ZD7288-sensitive current in these three animal models. C, Input resistance of GnRH neurons in male mice is altered by steroid milieu. *p < 0.001 versus intact (n = 11 and 16, respectively); p < 0.05 versus castrate plus estradiol (n = 12).

Discussion

The episodic release of GnRH is critical to fertility, as is the modulation of release frequency by gonadal steroid feedback (Knobil, 1972; Karsch, 1987). Ih is associated with rhythmic activity in pacemaker cells (Ludwig et al., 1998; Biel et al., 1999). By providing a persistent inward current at membrane potentials that are hyperpolarized relative to action potential threshold, Ih depolarizes the cell's membrane potential, allowing activation of other channels that generate additional inward current until action potential threshold is reached (Lupica et al., 2001; Robinson and Siegelbaum, 2003; Bean, 2007). Here, we demonstrate that in GnRH neurons Ih plays roles in setting excitability, spontaneous action potential firing, and, potentially, steroid feedback.

Similar to females (Zhang et al., 2007), ∼50% of GnRH neurons from male mice exhibited a hyperpolarization-activated current with characteristics indicating it is conducted via HCN channels. The current had a rapidly activating component, but was slow to activate completely and to deactivate, and did not inactivate. It was increased by cAMP, an allosteric activator of Ih (Bobker and Williams, 1989; DiFrancesco and Tortora, 1991; Banks et al., 1993; Erickson et al., 1993; Chen et al., 2001), was blocked by ZD7288 and Cs+, and was permeable to Na+ and K+ ions. Ba2+ blocked a component of the hyperpolarization-activated current, indicating GnRH neurons from male mice, like female mice, also exhibit IKir (Constanti and Galvan, 1983; Zhang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008). However, a ZD7288-sensitive current persisted after Ba2+ blockade. The pharmacological properties of the current strongly indicate it is Ih.

Activation and deactivation of Ih altered the functional properties of GnRH neurons. Rebound depolarization potentials are critical to controlling the spike patterns of several types of neurons exhibiting rhythmic activity (Bal et al., 1995). Activation of Ih during membrane hyperpolarization helps bring the cell back toward the threshold for action potential initiation. Likewise, deactivation of Ih during depolarization stabilizes membrane potential. Manipulations of membrane potential that would activate and deactivate Ih lead to increased and decreased action potential firing in GnRH neurons, respectively. Further, Ih contributes to the spontaneous activity of GnRH neurons; blocking Ih with ZD7288 reduced or eliminated action potential firing in GnRH neurons and caused frank hyperpolarization in some cells. This effect appears to be at least in part directly on GnRH neurons, as hyperpolarization persisted in some cells after blockade of both fast synaptic transmission and action potential initiation, and effects on GnRH neuron physiology were observed when the Ih blocker ZD7288 was applied intracellularly via the patch pipette, thus markedly limiting its interaction with upstream neurons. Blocking Ih also slowed the rate of recovery from the AHP, as has been observed in thalamic and hippocampal neurons (McCormick and Pape, 1990; Maccaferri et al., 1993; Nolan et al., 2007). This suggests Ih provides a subthreshold inward current in GnRH neurons that can contribute to action potential firing in these cells. Of note, these responses were observed in cells maintained within ∼10 mV hyperpolarized relative to the measured reversal potential for Ih, which would provide minimal activation for this channel and little driving force for current flow through activated channels. The marked effects of such a small current are likely attributable to the high input resistance of GnRH neurons (Sim et al., 2001; DeFazio and Moenter, 2002; Kuehl-Kovarik et al., 2002); this allows even small currents to impact substantially upon the firing properties of these cells (Chu and Moenter, 2006).

Generation of both bursts and single spikes appear to be fundamental characteristics of GnRH neurons. Blocking Ih reduced the ability of GnRH neurons to generate single spikes and decreased the number of spikes per burst. This is attributable, in part, to a reduction in the rate of recovery from the AHP; although Ih is slow to activate completely, a substantial part of this current activates on a time course enabling it to contribute to sculpting membrane potential between spikes in a burst. Ih may also interact with the current underlying after-depolarizing potentials in GnRH neurons, which is carried by TTX-sensitive sodium channels (Chu and Moenter, 2006). The persistence of this latter current after blockade of Ih, as well as contributions by other channels activated at membrane potentials more hyperpolarized than threshold (Zhang et al., 2009), likely accounts for the continued, albeit reduced, firing rate of many GnRH neurons after blockade of Ih. Burst firing in neuroendocrine systems increases hormone release (Dutton and Dyball, 1979), suggesting the changes in firing produced by Ih in GnRH neurons can impact upon functional hormone release from these cells. Because of its slow activation and deactivation properties, Ih is often considered to stabilize membrane potential. The present observations that blocking Ih in GnRH neurons leads to reduced activity suggests that the activity-generating aspects of this current may be predominant in these cells at least near the interspike membrane potential.

Gonadal steroids provide critical homeostatic feedback to regulate of GnRH neurons. This regulation likely involves both changes in synaptic transmission to GnRH neurons and altered intrinsic excitability (DeFazio et al., 2002; Nunemaker et al., 2002; Abe and Terasawa, 2005; Chu and Moenter, 2006; Wintermantel et al., 2006; Christian and Moenter, 2007; Dungan et al., 2007; Romanò et al., 2008; Chen and Moenter, 2009). In the present study, castration, which increases GnRH release, markedly increased Ih in GnRH neurons. In males, there is substantial conversion within the brain of circulating testosterone from the gonads to estradiol (Woolley, 2007), which provides the primary negative feedback signal to reduce the GnRH-dependent secretion of gonadotropins from the pituitary, as well as the activity of GnRH neurons (Roselli and Resko, 1990; Scott et al., 1997; Fisher et al., 1998; Pielecka and Moenter, 2006). Treatment of castrated male mice with estradiol restored Ih to levels observed in gonadal-intact mice, suggesting that estradiol-induced changes in Ih are a component of this negative feedback mechanism. Whether this is a direct or indirect action on GnRH neurons remains to be determined.

The present data suggest Ih plays important functional roles in GnRH neurons. A broader question is how to integrate these observations related to high-frequency activity in single cells with the overall pattern of hormone release from the GnRH neuronal network. This question awaits more data for a full answer, but some speculation is possible based on the present findings. GnRH neurons exhibit repeating bouts of firing activity that have been classified by fast Fourier transform into three rough period time domains: bursts (repeating with a period <100 s), clusters (100–1000 s), and episodes (>1000 s) (Nunemaker et al., 2003a, 2003b; Abe and Terasawa, 2005). The present study suggests that Ih contributes to the highest frequency of these domains—that of burst firing. Empirical evidence for how bursts are organized into longer period patterns is limited, thus any role of Ih in these processes is speculative; recent data suggest a molecularly uncharacterized calcium-activated potassium current may contribute to this organization (Lee et al., 2010). Both the number of spikes per burst and the interval between bursts are contributors to overall firing rate and these were altered when Ih was blocked. The long-term pattern of GnRH release (on the order of every 30 min in rodents) indicates alterations in network activity. An intriguing possibility is that intrinsic properties of individual GnRH neurons switch between relatively excitable and relatively quiescent states. It is possible that secondary to changes in neuromodulation, channel trafficking, or posttranslational modification, Ih is detectable only during the relatively excitable state. This might account for it being observed in only half of the neurons. Alternatively, HCN subunits may only be expressed in a subpopulation of GnRH neurons and thus render them spontaneously active driver cells for the network.

The overall pattern of GnRH release is likely sculpted by both intrinsic and synaptic mechanisms, but the emerging consensus is that episodic activity of GnRH neurons arises either at individual GnRH neurons or within networks of these cells (Moenter et al., 2003). Supporting observations include spontaneous firing in physically isolated GnRH neurons (Kuehl-Kovarik et al., 2002), pulsatile GnRH release from pure cultures of immortalized GnRH neurons (Catt et al., 1985; Martínez de la Escalera et al., 1992; Pitts et al., 2001), and spontaneous changes in the firing pattern of GnRH neurons in adult brain slices that is reflective of the pattern of GnRH and/or downstream pituitary hormone release from similarly treated animal (Levine et al., 1985b; Karsch, 1987; Moenter et al., 1992, 2003; Christian et al., 2005; Pielecka and Moenter, 2006; Pielecka et al., 2006). Episodic activity does not appear to involve macromolecular synthesis (Pitts et al., 2001) and appears to coordinate within networks of these cells at intervals that are similar to the occurrence of physiologically relevant hormone release in this system (Terasawa et al., 1999; Nunemaker et al., 2001). Together, the present data point to an important functional role for Ih in generating spontaneous activity in GnRH neurons, extending burst duration, enhancing recovery from the AHP, and being one intrinsic property potentially modulated by steroids to provide homeostatic feedback on GnRH neuronal activity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01 HD34860. We thank Debra Fisher for excellent technical assistance and Alison Roland, Justyna Pielecka-Fortuna, Jessica Kennett, Jianli Sun, and Pei-San Tsai for editorial comments.

References

- Abe H, Terasawa E. Firing pattern and rapid modulation of activity by estrogen in primate luteinizing hormone releasing hormone-1 neurons. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4312–4320. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo A, Kim B, Rasmusson RL, Bett G, Yeh J. Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels are expressed in rat hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons and immortalized GnRH neurons. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal T, von Krosigk M, McCormick DA. Role of the ferret perigeniculate nucleus in the generation of synchronized oscillations in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;483:665–685. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, Pearce RA, Smith PH. Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: voltage-clamp analysis and enhancement by norepinephrine and cAMP suggest a modulatory mechanism in the auditory brain stem. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1420–1432. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrell GK, Moenter SM, Caraty A, Karsch FJ. Seasonal changes of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the ewe. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:1130–1135. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry PH. JPCalc, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correcting junction potential measurements. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;51:107–116. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss DA, Viana F, Bellingham MC, Berger AJ. Characteristics and postnatal development of a hyperpolarization-activated inward current in rat hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:119–128. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Ludwig A, Zong X, Hofmann F. Hyperpolarization-activated cation channels: a multi-gene family. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;136:165–181. doi: 10.1007/BFb0032324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobker DH, Williams JT. Serotonin agonists inhibit synaptic potentials in the rat locus ceruleus in vitro via 5-hydroxytryptamine1A and 5-hydroxytryptammine1B receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;250:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma MM. Ion channel properties and episodic activity in isolated immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. J Membr Biol. 1993;136:85–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00241492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catt KJ, Loumaye E, Wynn PC, Iwashita M, Hirota K, Morgan RO, Chang JP. GnRH receptors and actions in the control of reproductive function. J Steroid Biochem. 1985;23:677–689. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4731(85)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Moenter SM. GABAergic transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons is regulated by GnRH in a concentration-dependent manner engaging multiple signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9809–9818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2509-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang J, Siegelbaum SA. Properties of hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker current defined by coassembly of HCN1 and HCN2 subunits and basal modulation by cyclic nucleotide. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:491–504. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.5.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA, Moenter SM. Estradiol induces diurnal shifts in GABA transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons to provide a neural signal for ovulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1913–1921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4738-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA, Mobley JL, Moenter SM. Diurnal and estradiol-dependent changes in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15682–15687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504270102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Moenter SM. Endogenous activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors modulates GABAergic transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and alters their firing rate: a possible local feedback circuit. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5740–5749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0913-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Moenter SM. Physiologic regulation of a tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium influx that mediates a slow afterdepolarization potential in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: possible implications for the central regulation of fertility. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11961–11973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3171-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Andrade J, Shupnik MA, Moenter SM. Differential regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and membrane properties by acutely applied estradiol: dependence on dose and estrogen receptor subtype. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5616–5627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0352-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarençon D, Renaudin M, Gourmelon P, Kerckhoeve A, Catérini R, Boivin E, Ellis P, Hille B, Fatôme M. Real-time spike detection in EEG signals using the wavelet transform and a dedicated digital signal processor card. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;70:5–14. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Cummins JT, Karsch FJ, Seeburg PH, Nikolics K. GnRH-associated peptide (GAP) is cosecreted with GnRH into the hypophyseal portal blood of ovariectomized sheep. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1987;143:665–671. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constanti A, Galvan M. Fast inward-rectifying current accounts for anomalous rectification in olfactory cortex neurones. J Physiol. 1983;335:153–178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel F, Penit-Soria J. Inward rectification and low threshold calcium conductance in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells: an in vitro study. J Physiol. 1986;372:1–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Estradiol feedback alters potassium currents and firing properties of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2255–2265. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio RA, Heger S, Ojeda SR, Moenter SM. Activation of A-type gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2872–2891. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFrancesco D, Tortora P. Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature. 1991;351:145–147. doi: 10.1038/351145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungan HM, Gottsch ML, Zeng H, Gragerov A, Bergmann JE, Vassilatis DK, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. The role of kisspeptin-GPR54 signaling in the tonic regulation and surge release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone/luteinizing hormone. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12088–12095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2748-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton A, Dyball RE. Phasic firing enhances vasopressin release from the rat neurohypophysis. J Physiol. 1979;290:433–440. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KR, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Electrophysiology of guinea-pig supraoptic neurones: role of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current in phasic firing. J Physiol. 1993;460:407–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CR, Graves KH, Parlow AF, Simpson ER. Characterization of mice deficient in aromatase (ArKO) because of targeted disruption of the cyp19 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6965–6970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi M, Mitoh Y, Kohjitani A, Matsuo R. Role of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) in pacemaker activity in area postrema neurons of rat brain slices. J Physiol. 2003;552:135–148. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini S, DiFrancesco D. Action of the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) blocker ZD 7288 in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Pflugers Arch. 1997;435:99–106. doi: 10.1007/s004240050488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell JV, Adams PR. Voltage-clamp analysis of muscarinic excitation in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1982;250:71–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ. Central actions of ovarian steroids in the feedback regulation of pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:365–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Ibrahim N, Lagrange AH, Wagner EJ. Estrogen modulation of K(+) channel activity in hypothalamic neurons involved in the control of the reproductive axis. Steroids. 2002;67:447–456. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobil E. Hormonal control of the menstrual cycle and ovulation in the rhesus monkey. Acta Endocrinol. 1972;166(Suppl):137–144. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.071s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl-Kovarik MC, Pouliot WA, Halterman GL, Handa RJ, Dudek FE, Partin KM. Episodic bursting activity and response to excitatory amino acids in acutely dissociated gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons genetically targeted with green fluorescent protein. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2313–2322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02313.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano K, Fueshko S, Gainer H, Wray S. Electrical and synaptic properties of embryonic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons in explant cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3918–3922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Duan W, Sneyd J, Herbison AE. Two slow calcium-activated afterhyperpolarization currents control burst firing dynamics in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6214–6224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6156-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipheimer RE, Bona-Gallo A, Gallo RV. The influence of progesterone and estradiol on the acute changes in pulsatile luteinizing hormone release induced by ovariectomy on diestrus day 1 in the rat. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1605–1612. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-5-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JE, Duffy MT. Simultaneous measurement of luteinizing hormone (LH)-releasing hormone, LH, and follicle-stimulating hormone release in intact and short-term castrate rats. Endocrinology. 1988;122:2211–2221. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-5-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JE, Bethea CL, Spies HG. In vitro gonadotropin-releasing hormone release from hypothalamic tissues of ovariectomized estrogen-treated cynomolgus macaques. Endocrinology. 1985a;116:431–438. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-1-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JE, Norman RL, Gliessman PM, Oyama TT, Bangsberg DR, Spies HG. In vivo gonadotropin-releasing hormone release and serum luteinizing hormone measurements in ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rhesus macaques. Endocrinology. 1985b;117:711–721. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, Zong X, Jeglitsch M, Hofmann F, Biel M. A family of hyperpolarization-activated mammalian cation channels. Nature. 1998;393:587–591. doi: 10.1038/31255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupica CR, Bell JA, Hoffman AF, Watson PL. Contribution of the hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) to membrane potential and GABA release in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:261–268. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A, Bal T, McCormick DA. Periodicity of thalamic spindle waves is abolished by ZD7288,a blocker of Ih. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3284–3289. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, McBain CJ. The hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) and its contribution to pacemaker activity in rat CA1 hippocampal stratum oriens-alveus interneurones. J Physiol. 1996;497:119–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Mangoni M, Lazzari A, DiFrancesco D. Properties of the hyperpolarization-activated current in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:2129–2136. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de la Escalera G, Choi AL, Weiner RI. Generation and synchronization of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses: intrinsic properties of the GT1–1 GnRH neuronal cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1852–1855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. A voltage-clamp analysis of inward (anomalous) rectification in mouse spinal sensory ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 1983;340:19–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Pape HC. Properties of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurons. J Physiol. 1990;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moenter SM, Brand RC, Karsch FJ. Dynamics of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion during the GnRH surge: insights into the mechanism of GnRH surge induction. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2978–2984. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1572305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moenter SM, DeFazio AR, Pitts GR, Nunemaker CS. Mechanisms underlying episodic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3022(03)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MF, Dudman JT, Dodson PD, Santoro B. HCN1 channels control resting and active integrative properties of stellate cells from layer II of the entorhinal cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12440–12451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2358-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Geusz ME, Herzog ED, Pitts GR, Moenter SM. Long-term recordings of networks of immortalized GnRH neurons reveal episodic patterns of electrical activity. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:86–93. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Estradiol-sensitive afferents modulate long-term episodic firing patterns of GnRH neurons. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2284–2292. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunemaker CS, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. A targeted extracellular approach for recording long-term firing patterns of excitable cells: a practical guide. Biol Proc Online. 2003a;5:53–62. doi: 10.1251/bpo46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunemaker CS, Straume M, DeFazio RA, Moenter SM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons generate interacting rhythms in multiple time domains. Endocrinology. 2003b;144:823–831. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC. Queer current and pacemaker: the hyperpolarization-activated cation current in neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:299–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC, McCormick DA. Noradrenaline and serotonin selectively modulate thalamic burst firing by enhancing a hyperpolarization-activated cation current. Nature. 1989;340:715–718. doi: 10.1038/340715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielecka J, Moenter SM. Effect of steroid milieu on gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neuron firing pattern and luteinizing hormone levels in male mice. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:931–937. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.049619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielecka J, Quaynor SD, Moenter SM. Androgens increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing activity in females and interfere with progesterone negative feedback. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1474–1479. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts GR, Nunemaker CS, Moenter SM. Cycles of transcription and translation do not comprise the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator in GT1 cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1858–1864. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Hyperpolarization-activated cation currents: from molecules to physiological function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:453–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanò N, Lee K, Abrahám IM, Jasoni CL, Herbison AE. Nonclassical estrogen modulation of presynaptic GABA terminals modulates calcium dynamics in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5335–5344. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Resko JA. Regulation of hypothalamic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone levels by testosterone and estradiol in male rhesus monkeys. Brain Res. 1990;509:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90563-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter R, Bader CR, Bernheim L. Development of anomalous rectification (Ih) and of a tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium current in embryonic quail neurones. J Physiol. 1991;442:127–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CJ, Kuehl DE, Ferreira SA, Jackson GL. Hypothalamic sites of action for testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and estrogen in the regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion in male sheep. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3686–3694. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin KS, Rothberg BS, Yellen G. Blocker state dependence and trapping in hyperpolarization-activated cation channels: evidence for an intracellular activation gate. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:91–101. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupnik MA. Effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone on rat gonadotropin gene transcription in vitro: requirement for pulsatile administration for luteinizing hormone-beta gene stimulation. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1444–1450. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim JA, Skynner MJ, Herbison AE. Heterogeneity in the basic membrane properties of postnatal gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the mouse. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1067–1075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01067.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain WJ, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Anomalous rectification in neurons from cat sensorimotor cortex in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:1555–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.5.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chu Z, Moenter SM. Diurnal in vivo and rapid in vitro effects of estradiol on voltage-gated calcium channels in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3912–3923. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6256-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter KJ, Song WJ, Sampson TL, Wuarin JP, Saunders JT, Dudek FE, Moenter SM. Genetic targeting of green fluorescent protein to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: characterization of whole-cell electrophysiological properties and morphology. Endocrinology. 2000;141:412–419. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E. Cellular mechanism of pulsatile LHRH release. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;112:283–295. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Schanhofer WK, Keen KL, Luchansky L. Intracellular Ca(2+) oscillations in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons derived from the embryonic olfactory placode of the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5898–5909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildt L, Häusler A, Marshall G, Hutchison JS, Plant TM, Belchetz PE, Knobil E. Frequency and amplitude of gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation and gonadotropin secretion in the rhesus monkey. Endocrinology. 1981;109:376–385. doi: 10.1210/endo-109-2-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, Bock D, Gröne HJ, Todman MG, Korach KS, Greiner E, Pérez CA, Schütz G, Herbison AE. Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron. 2006;52:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:657–680. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Bosch MA, Levine JE, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons express K(ATP) channels that are regulated by estrogen and responsive to glucose and metabolic inhibition. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10153–10164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1657-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Roepke TA, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. Kisspeptin depolarizes gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through activation of TRPC-like cationic channels. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4423–4434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5352-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Bosch MA, Rick EA, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK. 17Beta-estradiol regulation of T-type calcium channels in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10552–10562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2962-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]