Abstract

The present study examines a transactional, interpersonal model of depression in which stress generation (Hammen, 1991) in romantic relationships mediates the association between aspects of interpersonal style (i.e., attachment, dependency, and reassurance seeking) and depressive symptoms. It also examines an alternative, diathesis-stress model in which interpersonal style interacts with romantic stressors in predicting depressive symptoms. These models were tested in a sample of college women, both prospectively over a four-week period, as well as on a day-today basis using a daily diary methodology. Overall, there was strong evidence for a transactional, mediation model in which interpersonal style predicted romantic conflict stress, and in turn depressive symptoms. The alternative diathesis-stress model of depression was not supported. These results are interpreted in relation to previous research, and key limitations that should be addressed by future research are discussed.

Keywords: depression, stress, interpersonal style, attachment, dependency, reassurance seeking

It is widely accepted that stress plays an important role in vulnerability to depression (e.g., see Hammen, 2005, for a review). Diathesis-stress models, which emphasize that pre-existing vulnerabilities lead to disorder only in combination with stressors, focus on how the environment impacts individuals but are relatively silent about how individuals affect their environments. As such, there has been increasing emphasis on transactional processes, wherein individuals contribute to the occurrence of stressors in their lives, and these stressors, in turn, affect the individuals’ symptomatology.

Hammen (1991) applied this transactional model to depression, finding that depressed women experience more dependent stressors; that is, stressors they contributed to the occurrence of in a process labeled stress generation. It was suggested that these stressors predict further depression. Stress generation findings have been widely replicated (e.g., see Hammen, 2005, for a review), but the message of this research has often been oversimplified as “depression causes stress.” However, individuals with a history of depression have elevated levels of dependent stress even when they are not currently depressed (e.g., Hammen, 1991), suggesting that depression alone cannot explain stress generation. Yet few studies have examined the factors that impact stress generation, and in turn, depression. The current study aims to fill this gap by examining a transactional, interpersonal model of stress and depressed mood in female college students involved in romantic relationships. It focuses on three vulnerability factors for depression: attachment, reassurance seeking, and dependency/sociotropy.

Bowlby (1980) posited that insecurely attached individuals develop negative views of themselves and their relationships based on early experiences, making them more susceptible to depression. Indeed, insecure romantic attachment is associated with vulnerability to depression (e.g., Eberhart & Hammen, 2006; Whiffen, 2005). However, the mechanism of this effect is unclear. There is evidence that romantic attachment interacts with interpersonal stressors in predicting depressive symptoms (Hammen et al., 1995). There is also evidence that interpersonal stressors mediate the relationship between attachment and depressive symptoms (Hankin, Kassel, & Abela, 2005), but it is unclear if these results extend to romantic attachment.

Coyne (1976) suggested that depressed individuals excessively engage in reassurance seeking behaviors which elicit negative responses from others, ultimately increasing their depressive symptoms. Studies have demonstrated an association between reassurance seeking and depression, and further, that reassurance seeking interacts with achievement-related stress in predicting depressive symptoms (e.g., Joiner & Metalsky, 2001). To our knowledge, just one study has tested the transactional model: Pothoff et al. (1995) found that interpersonal stressors mediated the relationship between reassurance seeking and depressive symptoms.

Sociotropy (e.g., Beck, 1987) and dependency (e.g., Blatt, Quinlan, Chevron, McDonald, & Zuroff, 1982) capture another perspective on depression (“dependency” will be used to encompass both). Beck and Blatt suggested that individuals high in dependency excessively emphasize relationships, making them vulnerable to depression in response to interpersonal difficulties (e.g., Beck, 1987; Blatt et al., 1982). Many studies have found that dependency is associated with depression (e.g., Cogswell, Alloy, & Spasojevic, 2006), including a daily diary study (Stader & Hokanson, 1998), and diathesis-stress studies have found that dependency interacts with stressors in predicting depression (e.g., Shahar, Joiner, Zuroff, & Blatt, 2004). However, only one study has provided evidence for a transactional model in which stressors mediated the relationship between dependency and depressive symptoms (Shahar & Priel, 2003).

In sum, while there is evidence that attachment, reassurance-seeking, and dependency are associated with vulnerability to depression, there are gaps in this body of research. Most saliently, the mechanism through interpersonal style influences depressed mood is unclear. It is uncertain whether a diathesis-stress model or a transactional, stress generation model is most applicable, given that few studies test transactional models, and studies have not examined the different models in the same sample. As such, the current study examines both models. They are examined both prospectively over a four-week period and within a day, providing both macro- and micro-level examinations of vulnerability to depressed mood. The study excluded individuals with current disorders and controlled for current depressive symptomatology, in order to minimize effects of mood on interpersonal style. It focused on women because females are more susceptible to interpersonal stressors and depression (e.g., Shih, Eberhart, Hammen, & Brennan, 2006). It focused on romantic relationships because forming intimate relationships is a salient developmental task for the study’s college-aged sample (e.g., Erikson, 1950).

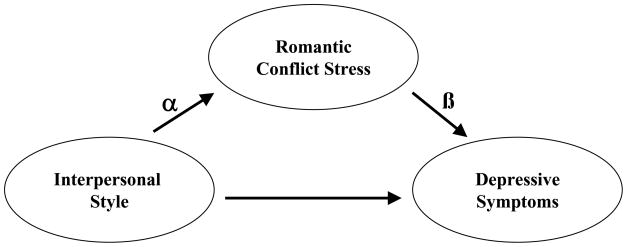

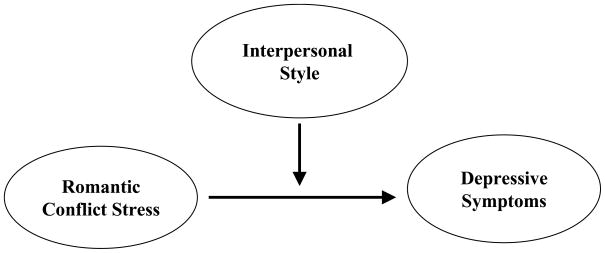

In a prior article, the authors laid the foundation for the present study by providing evidence that anxious attachment and reassurance seeking predict romantic conflict stressors over four weeks, and a variety of interpersonal behaviors predict the stressors on a daily basis (Eberhart & Hammen, in press). The current study expands on this research by examining models of the mechanism linking interpersonal style and stress to depressed mood, including a transactional model in which romantic conflict stressors mediate the relationship between interpersonal style and depressive symptoms (Figure 1) and a diathesis-stress model in which interpersonal style interacts with stressors in predicting symptoms (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Transactional (mediation) model of stress and depression.

Figure 2.

Diathesis-stress (moderation) model of stress and depression.

Method

Participants

A sample of 104 undergraduate women who met inclusion criteria was recruited from introductory psychology classes (mean age 18.82, SD = 1.24). All participants were currently involved in a romantic relationship (mean length 18.55 months, SD = 16.13) with daily contact with their partner. None had current depression or anxiety diagnoses. They were 35.6% Asian, 27.9% Caucasian, 9.6% Hispanic/Latina, 4.8% African American, 4.8% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 17.3% Biracial, and 40% had family incomes under $60,000. They received course credit for participation.

Procedures

Potential participants completed a screening questionnaire during a pre-testing session. . At baseline, participants were administered a diagnostic interview and questionnaires measuring depressive symptoms and interpersonal style. Next, they completed a daily survey online after 9 PM for 14 consecutive days. Four weeks after baseline, participants were administered a romantic life stress interview and a questionnaire measuring depressive symptoms.

Measures

Screening questionnaire

Demographics and inclusion criteria of involvement in a romantic relationship, daily contact with partner, and no current symptomatology were assessed.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-1-CV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996)

Select modules of the SCID were administered by trained and supervised female graduated and undergraduate students at baseline, in order to exclude individuals with current depression and common comorbid diagnoses and evaluate depression history. The SCID has good psychometric properties (First et al., 1996). Kappas could not be computed for current disorders due to low diagnosis frequencies. Twenty-six (24.3%) of participants had a past history of major depression (kappa = .93, for 43 cases).

Beck Depression Inventory – 2nd Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

The BDI-II was used to measure depressive symptoms at baseline and four-week follow-up. The BDI-II has convergent validity with the original BDI and excellent psychometric properties (Beck et al., 1996). In the current study, internal consistency was .86 at both baseline and follow-up. BDI-II scores will be referred to as BDI.

Experiences in Close Relationships - Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000)

This attachment measure consists of two 18-item subscales: avoidance (discomfort with closeness and depending on others) and anxiety (fear of rejection and abandonment). The ECR-R was empirically derived via Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses of attachment scales, resulting in a measure with superior psychometric properties (Fraley et al., 2000). In the current study, internal consistency was .95 for avoidance and .91 for anxiety.

Excessive Reassurance Seeking Scale (ERSS; Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992)

The ERRS measures tendency to seek feedback from others as to whether they truly care. Ratings are summed across the four items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of reassurance seeking. The scale has good validity and internal consistency (e.g., Joiner et al., 1992; Joiner & Metalsky, 2001). In the current study, internal consistency was .86.

3 Vector Dependency Inventory (3VDI; Pincus & Wilson, 2001)

The study examined two of the three dimensions measured by the 3VDI, exploitable dependence and love dependence (9 items each). Exploitable dependence measures suggestibility and eagerness to please others, while love dependence encompasses interpersonal sensitivity and affiliative behavior. Pincus and Wilson (2001) created the measure by conducting structural analyses on a large item pool created using several measures of dependency, and have provided evidence for its validity and internal consistency. It was altered for the current study so that items referred to romantic relationships. Internal consistency was .85 for exploitable dependence and .82 for love dependence.

Daily diary

The online questionnaire had the following components:

Interpersonal style questionnaire. Daily manifestations of the attachment dimensions, reassurance seeking, and dependency dimensions were measured using selected items from the original measures of these constructs, described above, which were modified to refer to specific behaviors that occurred within the romantic relationship that day (see Eberhart & Hammen, in press). Cronbach’s alpha, computed for each day, and averaged across days, ranged from .64 to .71 for scales comprised of 2 to 4 items. Exploitable dependency was not examined in the daily analyses because its daily internal consistency was inadequate (.32).

Romantic life events questionnaire. Participants completed a self-report checklist assessing daily romantic stressors. Romantic conflict stressors were operationally defined to include minor disagreements as well as major arguments. Stressor frequencies were tabulated for each day (daily mean = .91, SD = .91).

Outside stress. Participants rated the stressfulness of a) school and work, and b) relationships with family and friends, on a scale from 1 (not stressful) to 7 (very stressful).

Daily depressive symptoms. Symptoms were measured using a questionnaire reflecting DSM-IV criteria for depressive episodes (Hankin, Fraley, & Abela, 2005). Hankin et al. (2005) reported adequate consistency in composite scores over one week. In the current study, the 9 symptoms were represented by 10 items, as psychomotor agitation and retardation was split into 2 items. Participants rated how much they experienced each symptom that day on a 1–5 scale. Mean internal consistency across the 14 days of the current study was .71.

Daily diary compliance was good, as 93 participants (89%) completed 13–14 days, 11 (11%) completed 9–12 days, and none completed fewer than 9 days.

Romantic life stress interview

A semi-structured interview was used to measure acute stressors in participants’ romantic relationship over the course of the study. Narratives detailing the nature, consequences, and circumstances surrounding each event were presented to a rating team that was blind to participants’ subjective reactions to events and scores on other study variables. Events were evaluated on:

Objective impact. The team evaluated the impact the stressor would have on a typical person in a similar context, from 1 (no negative impact) to 5 (severe negative impact). There is evidence for the reliability and predictive validity of this methodology (e.g., Hammen, 1991).

Independence. The degree to which the event was caused by the participant was rated from 1 (entirely fateful) to 5 (entirely dependent on the individual). Events rated 3 or higher were considered “dependent” because there were at least in part due to the individual.

Conflict. The team evaluated whether each event involved conflict.

Intraclass correlation coefficients were .98 for objective impact and .96 for independence, and Kappa was 1.00 for conflict, based on independent team ratings of 47 events. Composite scores for romantic conflict stressors were computed by summing impact ratings for events coded as both dependent and conflict.

Results

Overview of Analyses

Four sets of analyses were conducted, two using prospective data, and two using daily diary data. Within each data set, one set of analyses tested the transactional model and the other tested the diathesis-stress model. For the daily hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses, a two-level model was utilized in which level 1 estimated within-subject differences and level 2 estimated between-subject differences. Level 1 variables were group-mean centered and level 2 variables were grand-mean centered. All analyses controlled for baseline BDI, and all HLM analyses also controlled for the passage of time over the 14 days.

Preliminary Analyses

Potentially confounding effects of depression history and non-romantic stressors were evaluated. While .05 is the threshold for significance for the study’s major analyses, a conservative threshold of .10 was used in evaluating potential covariates. An analysis of covariance controlling for baseline BDI revealed that past major depression did not predict BDI at four-week follow-up, p > .10. HLM analyses controlling for baseline BDI and time also found no effect of depression history on daily depressive symptoms, p > .10. As such, there was no need to control for prior depression.

With respect to outside stress, hierarchical linear regression analyses controlling for baseline BDI revealed that average daily achievement stress did not predict BDI at four-week follow-up, p > .10. In contrast, average daily social stress outside the romantic relationship marginally predicted follow-up BDI, b = .91, SE = .53, t(3,103) = 1.70, p ≤ .10. Thus, outside social stress was controlled for in all analyses in which conflict stress predicted follow-up depressive symptoms. HLM analyses controlling for baseline BDI and time revealed that daily achievement stress, b = .75, SE = .09, t(103) = 8.20, p ≤ .001, and social stress, b = .97, SE = .09, t(103) = 11.20, p ≤ .001, predicted daily depressive symptoms. Thus, both were controlled for in all analyses in which daily conflict stress predicted daily depressive symptoms.

Transactional (Mediation) Model

Mediation hypotheses were tested according to the guidelines outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) and MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). There is evidence that the Baron and Kenny (1986) causal steps approach to testing mediation has low power compared to product of coefficients methods (MacKinnon et al., 2002), so Sobel’s (1982) product of coefficients was used to evaluate mediation.

Prospective data

Hierarchical linear regression analyses controlling for baseline BDI examined whether baseline interpersonal style and conflict stressors over the course of the study predicted depressive symptoms at four-week follow-up. Baseline depressive symptoms, entered in the first step, significantly predicted follow-up BDI, b = .53, SE = .08, t(1, 102) = 6.76, p ≤ .001. This first step was the same for all prospective analyses. In the second step, the interpersonal style variables were individually entered in a series of separate regressions predicting BDI. Conflict stress was entered in the third step, which also controlled for social stress outside the romantic relationship.

Results indicated that anxious attachment and reassurance seeking significantly (p ≤ .05) predicted follow-up depressive symptoms, while avoidant attachment, exploitable dependency, and love dependency did not predict symptoms (see Table 1). Conflict stress predicted depressive symptoms, controlling for each of these variables (β path; see Figure 1). Previous research using this data set (Eberhart & Hammen, in press) established that anxious attachment and reassurance seeking were also significant predictors of conflict stressors (α path in Figure 1). Moreover, a Sobel statistic indicated that mediation was significant for anxious attachment; it significantly predicted conflict stress, and in turn, depressive symptoms at four-week follow-up, Sobel αβ = 2.37, p ≤ .05. Using MacKinnon, Warsi, and Dwyer’s (1995) calculation method, 56% percent of the prospective effect of anxious attachment on depressive symptoms was explained by conflict stress. Similarly, a Sobel statistic indicated that conflict stress significantly mediated the effect of reassurance seeking on follow-up depressive symptoms, Sobel αβ = 2.37, p ≤ .05, with 63% of the effect explained by conflict stress.

Table 1.

Hierarchical Linear Regression Prospectively Predicting Depressive Symptoms from Baseline Interpersonal Style and Conflict Stress over the Course of the Study

| b | SE | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2: Anxious Attachment | 1.02 | .48 | 2.11* |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .60 | .14 | 4.47*** |

| Step 2: Avoidant Attachment | .48 | .42 | 1.14 |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .63 | .13 | 4.84*** |

| Step 2: Reassurance Seeking | .68 | .34 | 1.97* |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .61 | .13 | 4.56*** |

| Step 2: Exploitable Dependency | .06 | .05 | 1.15 |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .63 | .13 | 4.78*** |

| Step 2: Love Dependency | .04 | .07 | .63 |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .66 | .13 | 5.07*** |

Note. Baseline BDI was controlled for in Step 1 of all analyses. Outside social stress was controlled for in Step 3, df = 103,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .001.

Daily diary data

HLM analyses were used to examine whether daily interpersonal behaviors and conflict stressors predict daily depressive symptoms, controlling for baseline BDI, time, and daily social and achievement stress outside the romantic relationship.

Baseline depressive symptoms, entered in the first step, significantly predicted daily depressive symptoms, b = .29, SE = .05, t(102) = 5.94, p ≤ .001, controlling for time. This first step was the same for all HLM analyses. In the second step, each category of interpersonal behavior was individually examined in a series of analyses, controlling for time and baseline BDI. Each type of interpersonal behavior significantly predicted daily depressive symptoms, including anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, reassurance seeking, and love dependency behaviors (see Table 2). Conflict stressors were entered in the third step, which controlled for outside stress in addition to time, baseline BDI, and the interpersonal behavior being examined. In all instances, conflict stress predicted daily depressive symptoms even when these other factors were controlled (β path in Figure 1; see Table 3). Previous research using this data set (Eberhart & Hammen, in press) has established that each of these variables is also a significant predictor of conflict stressors (α path). Sobel αβ statistics confirmed that daily conflict stress significantly mediated the relationship between each of the daily measures of interpersonal behaviors and daily depressive symptoms. Table 3 lists the Sobel statistics and the proportion of the effect explained by the mediator.

Table 2.

HLM Predicting Daily Depressive Symptoms from Interpersonal Behaviors and Conflict Stress

| b | SE | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2: Anxious Attachment behaviors | 2.88 | .45 | 6.35*** |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .46 | .09 | 5.14*** |

| Step 2: Avoidant Attachment behaviors | 1.50 | .25 | 6.05*** |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .44 | .10 | 4.44*** |

| Step 2: Reassurance Seeking behaviors | 1.43 | .30 | 4.83*** |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .47 | .09 | 5.15*** |

| Step 2: Love Dependency behaviors | .86 | .16 | 5.52*** |

| Step 3: Conflict Stress | .51 | .09 | 5.67*** |

Note. Time was controlled for on level 1 of all analyses and baseline BDI was controlled for on level 2 of all analyses, in Step 1. Outside social stress and achievement stress were controlled for on level 1 in Step 3. Time was entered as a fixed variable, and all other variables were entered as random variables, df = 103,

p ≤ .001.

Table 3.

Mediation Analyses Examining Daily Conflict Stress as a Mediator of the Relationship between Daily Interpersonal Behaviors and Daily Depressive Symptoms

| Sobel αβ | % Mediated | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxious Attachment → Conflict Stress → Depressive Symptoms | 4.70*** | 19% |

| Avoidant Attachment → Conflict Stress → Depressive Symptoms | 4.22*** | 31% |

| Reassurance Seeking → Conflict Stress → Depressive Symptoms | 4.40*** | 28% |

| Love Dependency → Conflict Stress → Depressive Symptoms | 2.87** | 17% |

Note.

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Diathesis-Stress (Moderation) Model

Moderation hypotheses were tested according to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) guidelines.

Prospective data

Hierarchical linear regression analyses were used to examine the interaction between baseline interpersonal style and conflict stressors in predicting BDI at four-week follow-up. The equations entered each interpersonal style variable, conflict stress, and the interaction between the interpersonal style variable and conflict stress, controlling for baseline BDI and outside social stress. None of the five interpersonal style variables was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms in interaction with conflict stress (p > .05).

Daily diary data

HLM analyses examined whether the interactions between daily interpersonal style and daily conflict stressors were significant after controlling for the main effects of the interpersonal style variable and conflict stressors, as well as time, baseline BDI, and stress outside the romantic relationship. None of the interactions were significant (p > .05).

Discussion

The current study examined the mechanism through which interpersonal style impacts depressive symptoms. It tested two interpersonal models of stress and depression: a transactional model in which romantic conflict stress generation mediates the relationship between interpersonal style and depressive symptoms, and a diathesis-stress model in which interpersonal vulnerabilities interact with conflict stressors in predicting depressive symptoms. These effects were examined both prospectively over a four-week period and cross-sectionally using a daily diary. Overall, the results supported the transactional model but not the diathesis-stress model.

In support of the transactional model, the study found that romantic conflict stress mediated the effects of anxious attachment and reassurance seeking on depressive symptoms over four-week period. Further, daily conflict stress mediated the effects of anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, reassurance seeking, and love dependency behaviors on daily depressive symptoms. The results are consistent with previous findings that depression is associated with a variety of interpersonal vulnerabilities (e.g., Cogswell et al., 2006; Joiner & Metalsky, 2001; Whiffen, 2005). However, few studies have examined stress generation a mediator of these effects, or examined the immediate effects of interpersonal behaviors on daily mood. The current study provides evidence that the transactional model helps explain both prospective changes in symptoms and daily mood, and that the model is applicable to romantic stressors, in particular.

The study also examined an alternative diathesis-stress model. None of the interpersonal style variables interacted with conflict stress in predicting depressive symptoms at follow-up or on a daily basis. The dearth of significant results is surprising in light of previous research that has found support for diathesis-stress models of the relationship between interpersonal style, stress, and depression (e.g., Hammen et al., 1995). Perhaps the current study uncovered different findings in part because it focused on romantic relationships, and the diathesis-stress model may be less applicable to the romantic domain.

The study expands on theories of depression put forth by Bowlby (1980), Beck (Beck et al., 1983), Blatt (Blatt et al., 1982), and Coyne (1976) by elucidating a mechanism through which interpersonal style impacts depressed mood. It provides evidence that individuals are not passive recipients of the stressors that make them susceptible to depression; rather, their interpersonal style and the specific interpersonal behaviors they engage in contribute to depressive symptoms via their impact on stress generation.

While the transactional approach is a better fit for the interpersonal model tested in the current study, future research is needed to determine whether this approach is applicable to other models of depression, such as cognitive models. It is possible that different vulnerability mechanisms are applicable to different kinds of risk factors. Indeed, it is likely that both stress generation and diathesis-stress components can be integrated into a single, more comprehensive model of vulnerability to depression (e.g., Hankin & Abramson, 2001).

The current study has some strengths, including use of daily diaries and life stress interviews, and exclusion of individuals who had current disorders at baseline so the direction of causality is more clear. However, limitations are noted. The sample consisted of college students, and it is unclear whether the findings would extend to other populations. It was limited to women, so the findings may not be applicable to men, especially in light of evidence that gender moderates the relationship between interpersonal stress and depression (e.g., Shih et al., 2006). The study focused on romantic relationships, and further research is needed to determine whether the findings would extend to stress in other domains.

In addition, the study’s daily diary analyses were cross-sectional, and thus could not discern the direction of causality. The prospective analyses addressed this issue by providing evidence that interpersonal style influences later depressive symptoms. However, they examined a relatively short four-week period, which made it difficult to capture clinically significant changes in depressive symptoms. Finally, while the study aimed to examine the effects of personal characteristics and behaviors, it is possible that the results are driven by characteristics of participants’ romantic relationships. While a portion of the variance assessed by attachment measures reflects characteristics of individuals, a portion reflects characteristics of the relationship an individual is in (e.g., Buist, Dekovíc, Meeus, & van Aken, 2004; Cook, 2000). As such, future research should examine the relative contributions of the individual versus the relationship in these processes.

Despite these limitations, the present study represents a further step in understanding vulnerability to depressive symptoms in young women. It provides support for a transactional, interpersonal model in which interpersonal style impacts depressive symptoms via its influence on stress generation in romantic relationships.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported in part by a National Research Service Award postdoctoral fellowship (NIMH Grant 5-T32-MH14584) awarded to Nicole Eberhart.

Footnotes

This article is based in part on the doctoral dissertation of Nicole Eberhart, chaired by Constance Hammen.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1987;1:2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM, Chevron ES, McDonald C, Zuroff DC. Dependency and self-criticism: Psychological dimensions of depression. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1982;150:113–124. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss, sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social origins of depression. London: Free Press; 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Dekovic M, Meeus WH, van Aken MAG. Attachment in adolescence: A social relations model analysis. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:826–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell A, Alloy LB, Spasojevic J. Neediness and interpersonal life stress: Does congruency predict depression? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL. Understanding attachment security in family context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:285–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart NK, Hammen CL. Interpersonal predictors of onset of depression during the transition to adulthood. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart NK, Hammen CL. Interpersonal predictors of stress generation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi: 10.1177/0146167208329857. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Childhood and society. New York: W.W. Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-1-CV) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:350–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL. The generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen CL, Burge D, Daley SE, Davila J, Paley B, Rudolph KD. Interpersonal attachment cognitions and prediction of symptomatic responses to interpersonal stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:436–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Fraley RC, Abela JRZ. Daily depression and cognitions about stress: Evidence for a traitlike depressogenic cognitive style and the prediction of depressive symptoms in a prospective daily diary study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:673–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Kassel JD, Abela JRZ. Adult attachment dimensions and specificity of emotional distress symptoms: Prospective investigations of cognitive risk and interpersonal stress generation as mediating mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:136–151. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Metalsky GI. Excessive reassurance seeking: delineating a risk factor involved in the development of depressive symptoms. Psychological Science. 2001;12:371–378. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Hammen C, Daley SE, Burge D, Davila J. Sociotropic and autonomous personality styles: Contributions to chronic life stress. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus AL, Wilson KR. Interpersonal variability in dependent personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:223–251. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff JG, Holahan CJ, Joiner TE. Reassurance seeking, stress generation, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:664–670. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Joiner TEJ, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. Personality, interpersonal behavior, and depression: Co-existence of stress-specific moderating and mediating effects. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:1583–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Priel B. Active vulnerability, adolescent distress, and the mediating/suppressing role of life events. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH. Sex differences in stress generation: An examination of sociotropy/autonomy, stress, and depressive symptoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:434–446. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:103–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stader SR, Hokanson JE. Psychosocial antecedents of depressive symptoms: An evaluation using daily experiences methodology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:17–26. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE. The role of partner characteristics in attachment insecurity and depressive symptoms. Personal Relationships. 2005;12:407–423. [Google Scholar]