Abstract

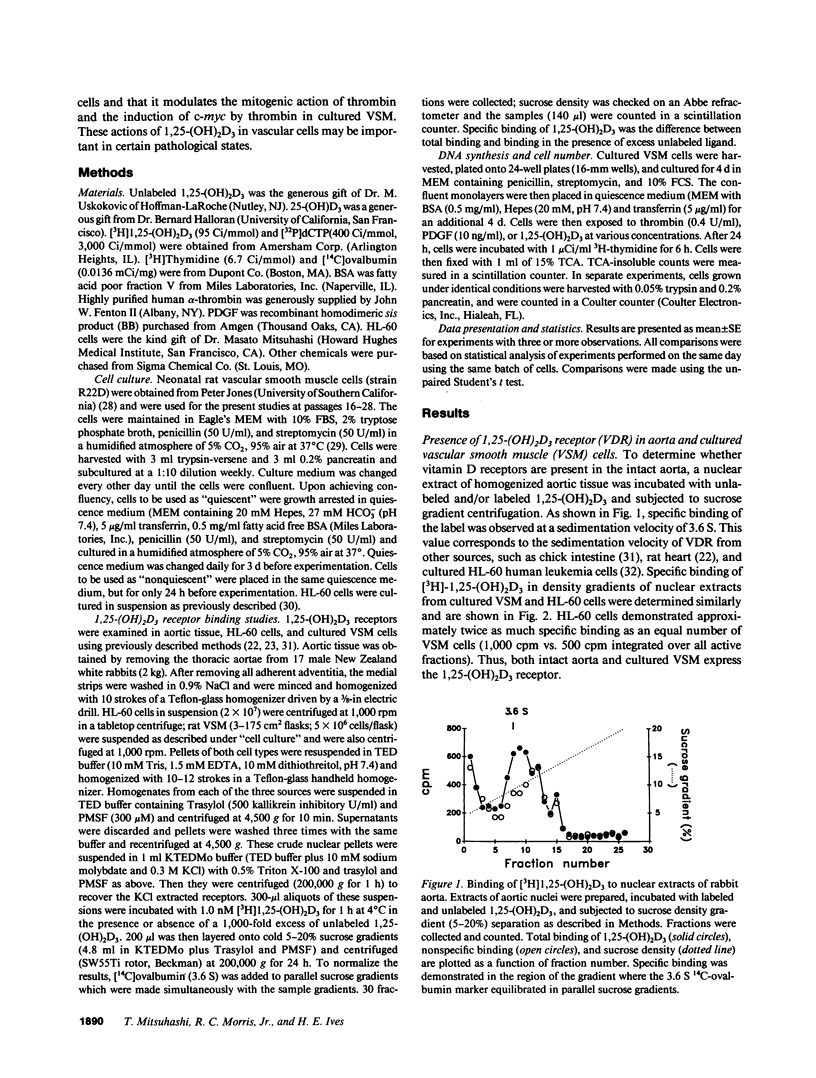

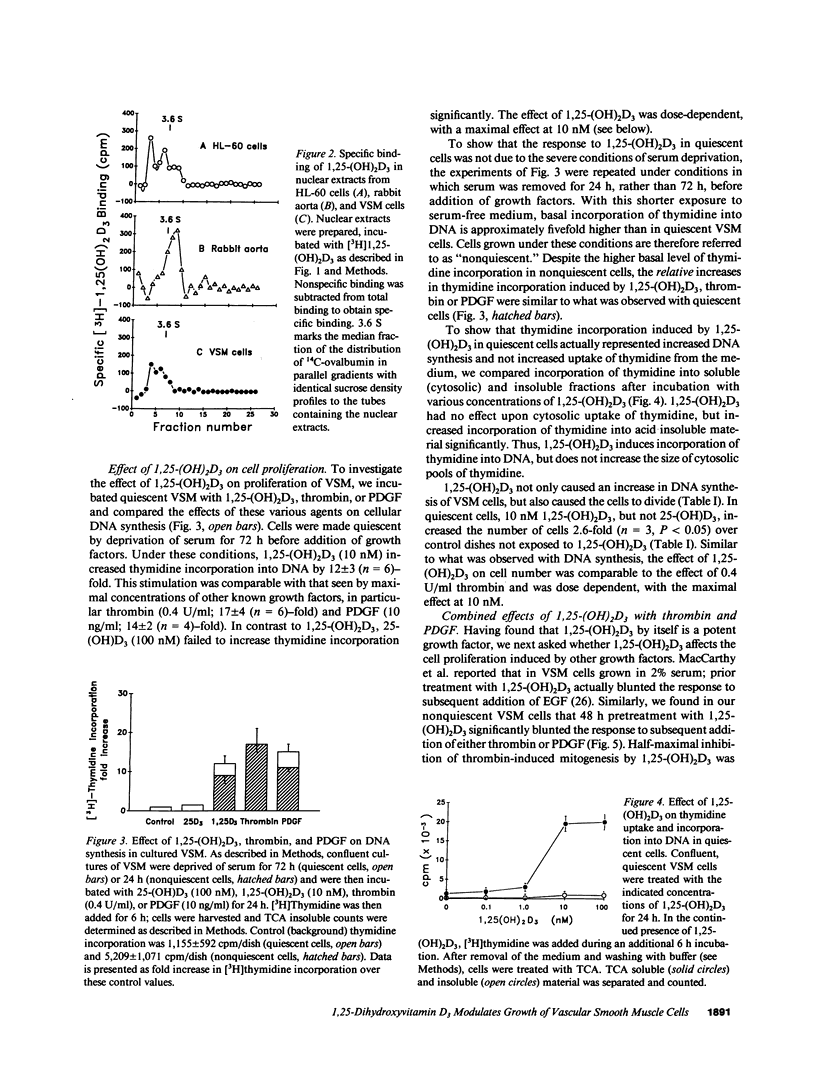

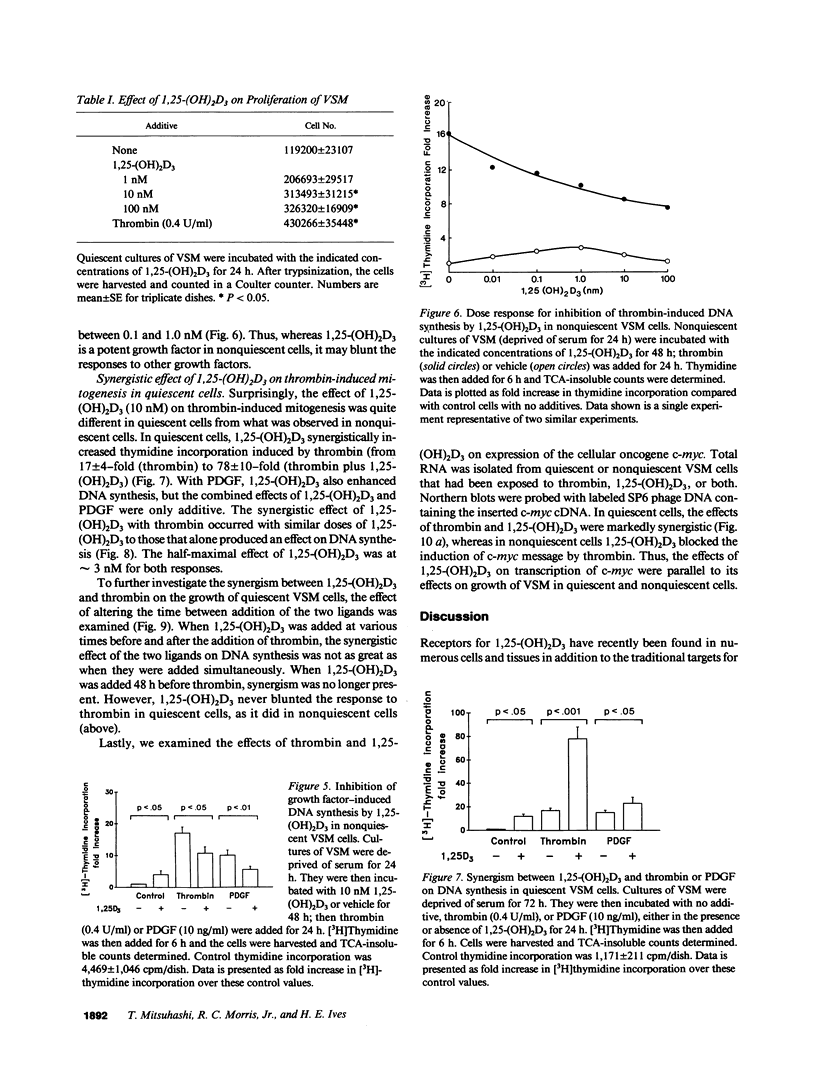

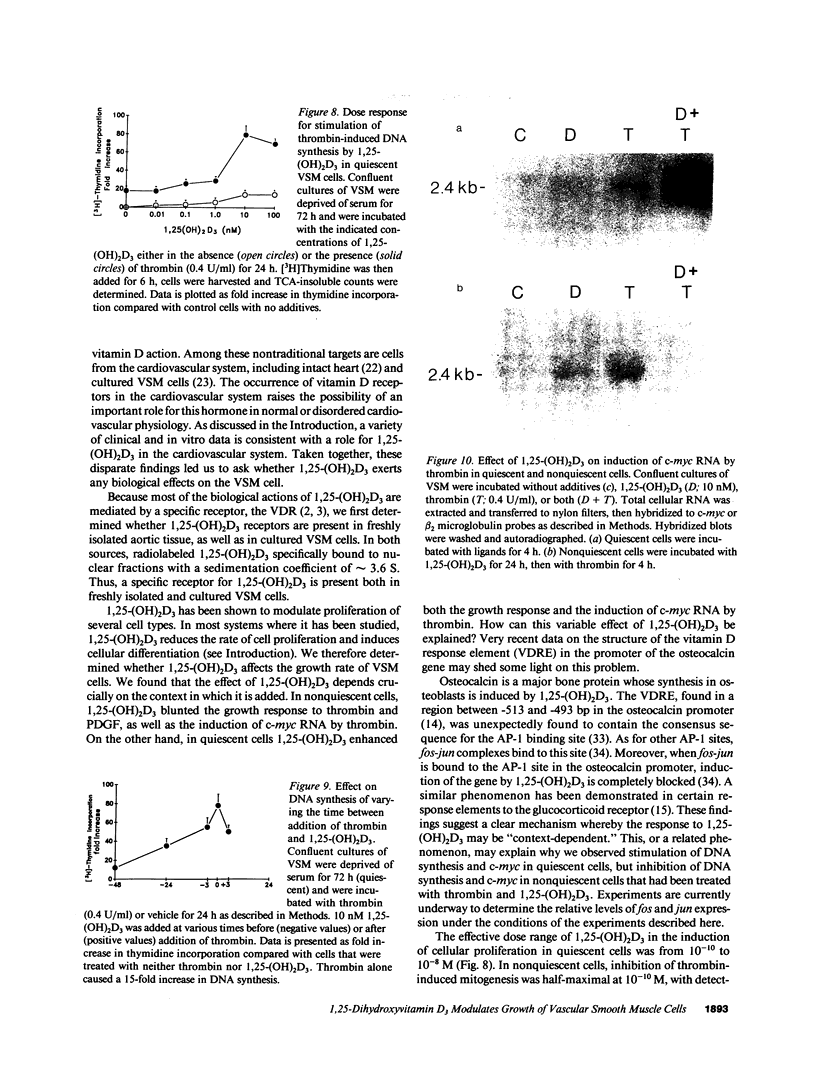

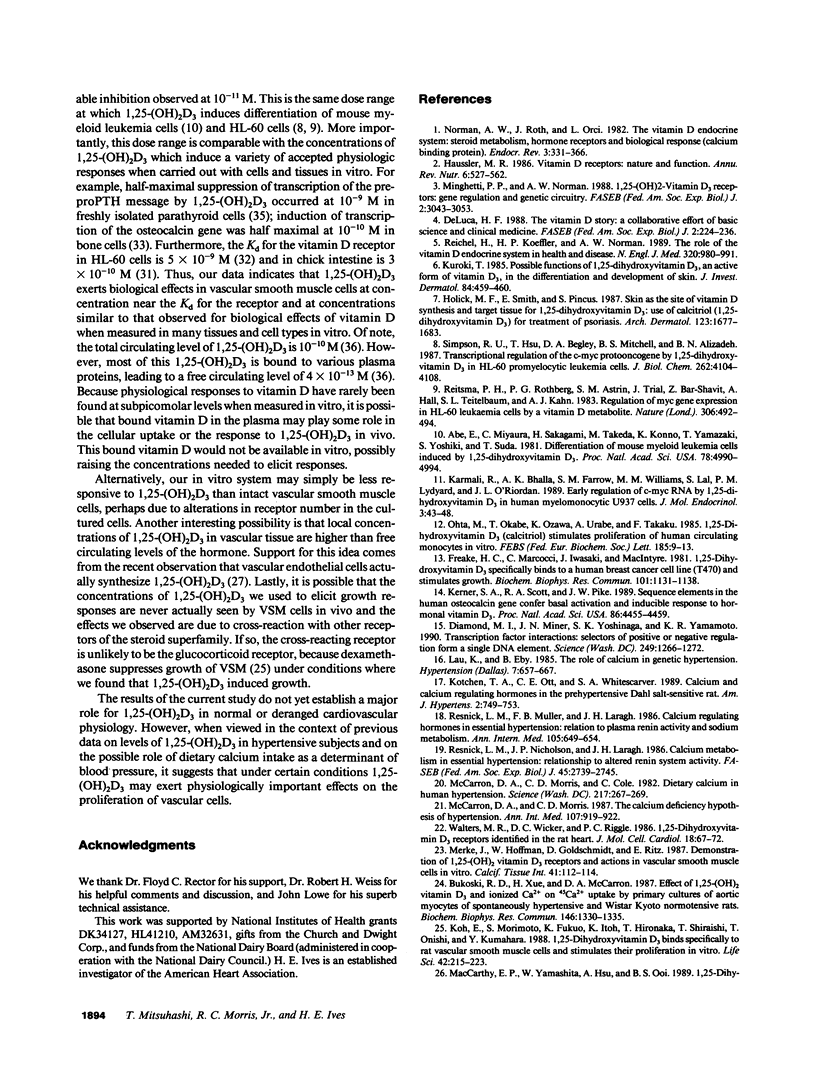

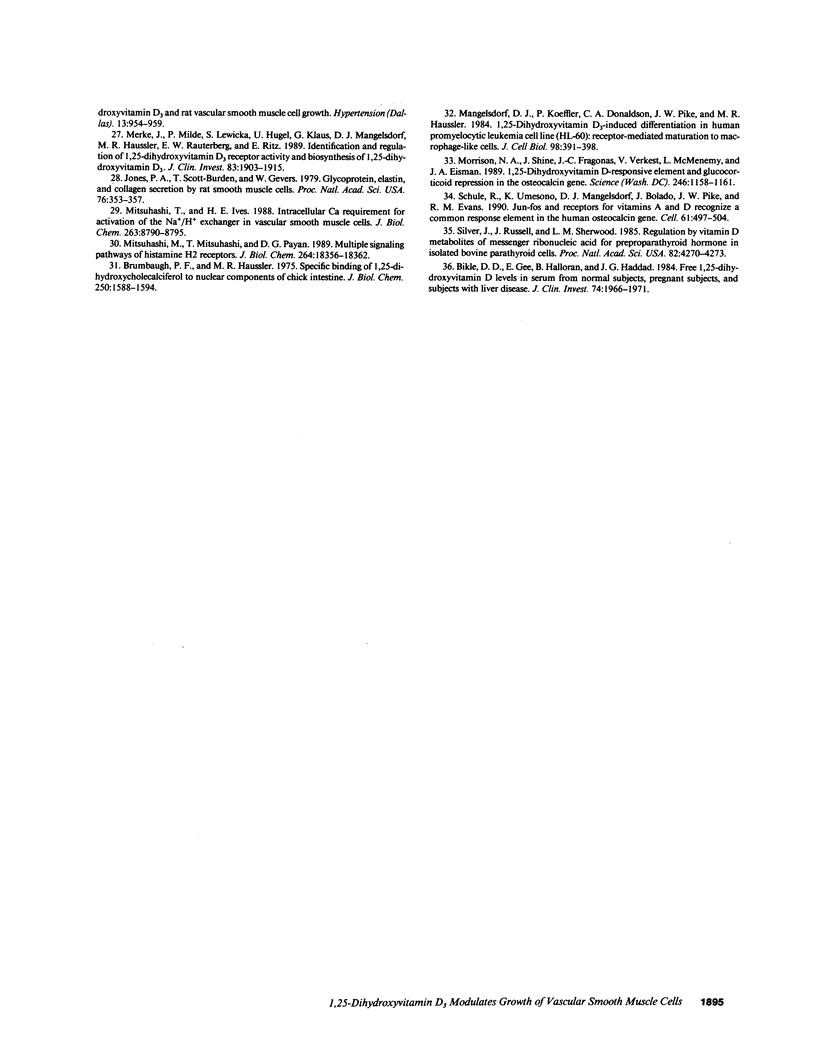

We examined the effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3(1,25-(OH)2D3) on the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cells. Receptors for 1,25-(OH)2D3 were demonstrated in fresh rabbit aortic tissue and in cultured rat VSM using binding of [3H]-1,25-(OH)2D3 in sucrose density gradients of the tissue or cell homogenates. The receptor sedimented at 3.6 S, the sedimentation velocity of 1,25-(OH)2D3 receptors from other sources. 1,25-(OH)2D3 dramatically altered the growth of VSM, but this effect depended importantly on the basal conditions in which the cells were grown. In quiescent VSM deprived of serum for 72 h, 1,25-(OH)2D3 (0.1-10 nM), but not 25-(OH)D3 (up to 100 nM) increased thymidine incorporation up to 12-fold and cell number up to 2.6-fold compared with controls. The maximal effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on thymidine incorporation was similar to the maximal effect of the growth factors alpha-thrombin or PDGF. Furthermore, the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and thrombin on thymidine incorporation in quiescent cells were markedly synergistic, yielding a 78-fold increase in thymidine incorporation when both agents were added simultaneously. In "nonquiescent cells" which were exposed to serum-free medium for only 24 h, 1,25-(OH)2D3 (10 nM) also increased DNA synthesis 10-fold compared with controls. However, in striking contrast to what was observed in quiescent cells, 1,25-(OH)2D3 diminished the mitogenic response to thrombin by as much as 50% in nonquiescent cells. 1,25-(OH)2D3 also modulated the transcription of c-myc in response to thrombin. In quiescent cells, transcription was enhanced by 1,25-(OH)2D3, whereas in nonquiescent cells, thrombin-induced c-myc transcription was blunted. Thus, 1,25-(OH)2D3 is a potent modulator of the growth of cultured VSM. The direction of this modulation depends strongly on the conditions under which the cells are cultured.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abe E., Miyaura C., Sakagami H., Takeda M., Konno K., Yamazaki T., Yoshiki S., Suda T. Differentiation of mouse myeloid leukemia cells induced by 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Aug;78(8):4990–4994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle D. D., Gee E., Halloran B., Haddad J. G. Free 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in serum from normal subjects, pregnant subjects, and subjects with liver disease. J Clin Invest. 1984 Dec;74(6):1966–1971. doi: 10.1172/JCI111617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh P. F., Haussler M. R. Specific binding of 1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol to nuclear components of chick intestine. J Biol Chem. 1975 Feb 25;250(4):1588–1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukoski R. D., Xue H., McCarron D. A. Effect of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 and ionized Ca2+ on 45Ca uptake by primary cultures of aortic myocytes of spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar Kyoto normotensive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Aug 14;146(3):1330–1335. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca H. F. The vitamin D story: a collaborative effort of basic science and clinical medicine. FASEB J. 1988 Mar 1;2(3):224–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M. I., Miner J. N., Yoshinaga S. K., Yamamoto K. R. Transcription factor interactions: selectors of positive or negative regulation from a single DNA element. Science. 1990 Sep 14;249(4974):1266–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.2119054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freake H. C., Marcocci C., Iwasaki J., MacIntyre I. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 specifically binds to a human breast cancer cell line (T47D) and stimulates growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981 Aug 31;101(4):1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91565-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haussler M. R. Vitamin D receptors: nature and function. Annu Rev Nutr. 1986;6:527–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F., Smith E., Pincus S. Skin as the site of vitamin D synthesis and target tissue for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Use of calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) for treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1987 Dec;123(12):1677–1683a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. A., Scott-Burden T., Gevers W. Glycoprotein, elastin, and collagen secretion by rat smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Jan;76(1):353–357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali R., Bhalla A. K., Farrow S. M., Williams M. M., Lal S., Lydyard P. M., O'Riordan J. L. Early regulation of c-myc mRNA by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human myelomonocytic U937 cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 1989 Jul;3(1):43–48. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0030043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner S. A., Scott R. A., Pike J. W. Sequence elements in the human osteocalcin gene confer basal activation and inducible response to hormonal vitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jun;86(12):4455–4459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh E., Morimoto S., Fukuo K., Itoh K., Hironaka T., Shiraishi T., Onishi T., Kumahara Y. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 binds specifically to rat vascular smooth muscle cells and stimulates their proliferation in vitro. Life Sci. 1988;42(2):215–223. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchen T. A., Ott C. E., Whitescarver S. A., Resnick L. M., Gertner J. M., Blehschmidt N. G. Calcium and calcium regulating hormones in the "prehypertensive" Dahl salt sensitive rat (calcium and salt sensitive hypertension). Am J Hypertens. 1989 Oct;2(10):747–753. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.10.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki T. Possible functions of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, an active form of vitamin D3, in the differentiation and development of skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1985 Jun;84(6):459–460. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12272331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K., Eby B. The role of calcium in genetic hypertension. Hypertension. 1985 Sep-Oct;7(5):657–667. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf D. J., Koeffler H. P., Donaldson C. A., Pike J. W., Haussler M. R. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation in a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60): receptor-mediated maturation to macrophage-like cells. J Cell Biol. 1984 Feb;98(2):391–398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron D. A., Morris C. D., Cole C. Dietary calcium in human hypertension. Science. 1982 Jul 16;217(4556):267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.7089566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron D. A., Morris C. D. The calcium deficiency hypothesis of hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1987 Dec;107(6):919–922. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-6-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merke J., Hofmann W., Goldschmidt D., Ritz E. Demonstration of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 receptors and actions in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987 Aug;41(2):112–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02555253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merke J., Milde P., Lewicka S., Hügel U., Klaus G., Mangelsdorf D. J., Haussler M. R., Rauterberg E. W., Ritz E. Identification and regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor activity and biosynthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Studies in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells and human dermal capillaries. J Clin Invest. 1989 Jun;83(6):1903–1915. doi: 10.1172/JCI114097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti P. P., Norman A. W. 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 receptors: gene regulation and genetic circuitry. FASEB J. 1988 Dec;2(15):3043–3053. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.15.2847948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi M., Mitsuhashi T., Payan D. G. Multiple signaling pathways of histamine H2 receptors. Identification of an H2 receptor-dependent Ca2+ mobilization pathway in human HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1989 Nov 5;264(31):18356–18362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi T., Ives H. E. Intracellular Ca2+ requirement for activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jun 25;263(18):8790–8795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison N. A., Shine J., Fragonas J. C., Verkest V., McMenemy M. L., Eisman J. A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-responsive element and glucocorticoid repression in the osteocalcin gene. Science. 1989 Dec 1;246(4934):1158–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.2588000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman A. W., Roth J., Orci L. The vitamin D endocrine system: steroid metabolism, hormone receptors, and biological response (calcium binding proteins). Endocr Rev. 1982 Fall;3(4):331–366. doi: 10.1210/edrv-3-4-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M., Okabe T., Ozawa K., Urabe A., Takaku F. 1 alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol) stimulates proliferation of human circulating monocytes in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1985 Jun 3;185(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel H., Koeffler H. P., Norman A. W. The role of the vitamin D endocrine system in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 1989 Apr 13;320(15):980–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198904133201506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsma P. H., Rothberg P. G., Astrin S. M., Trial J., Bar-Shavit Z., Hall A., Teitelbaum S. L., Kahn A. J. Regulation of myc gene expression in HL-60 leukaemia cells by a vitamin D metabolite. Nature. 1983 Dec 1;306(5942):492–494. doi: 10.1038/306492a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick L. M., Müller F. B., Laragh J. H. Calcium-regulating hormones in essential hypertension. Relation to plasma renin activity and sodium metabolism. Ann Intern Med. 1986 Nov;105(5):649–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-5-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick L. M., Nicholson J. P., Laragh J. H. Calcium metabolism in essential hypertension: relationship to altered renin system activity. Fed Proc. 1986 Nov;45(12):2739–2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüle R., Umesono K., Mangelsdorf D. J., Bolado J., Pike J. W., Evans R. M. Jun-Fos and receptors for vitamins A and D recognize a common response element in the human osteocalcin gene. Cell. 1990 May 4;61(3):497–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90531-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J., Russell J., Sherwood L. M. Regulation by vitamin D metabolites of messenger ribonucleic acid for preproparathyroid hormone in isolated bovine parathyroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jun;82(12):4270–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson R. U., Hsu T., Begley D. A., Mitchell B. S., Alizadeh B. N. Transcriptional regulation of the c-myc protooncogene by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in HL-60 promyelocytic leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1987 Mar 25;262(9):4104–4108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters M. R., Wicker D. C., Riggle P. C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors identified in the rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1986 Jan;18(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(86)80983-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]