Abstract

Behavioral research indicates that healthy aging is accompanied by maintenance of voluntary attentional function in many situations, suggesting older adults are able to use attention to enhance and suppress neural activity. However, other experiments show increased distractibility with age, suggesting a failure of attention. One hypothesis for these apparently conflicting findings is that older adults experience a greater sensory processing load at baseline compared to younger adults. In this situation, older adults might successfully modulate sensory cortical activity relative to a baseline referent condition, but the increased baseline load results in more activity than younger adults after attentional modulation. This hypothesis was tested by comparing average functional brain activity in auditory cortex using quantitative perfusion imaging during resting state and steady-state visual conditions. It was observed that older adults demonstrated greater processing of task-irrelevant auditory background noise than younger adults in both conditions. As expected, auditory activity was attenuated relative to rest during a visually engaging task for both older and younger participants. However, older adults continued to show greater auditory processing than their younger counterparts even after this task modulation. Furthermore, auditory activity during the visual task was predictive of cross-sensory distraction on a behavioral task in older adults. Together, these findings suggest that older adults are more distractible than younger, and the cause of this increased distractibility may lie in baseline brain functioning.

Keywords: aging, attention, cerebral perfusion, cross-sensory, functional imaging

1. Introduction

Behavioral research investigating the effects of aging on attention presents an apparent paradox in the aging brain – in many instances, older adults are able engage selective attention as effectively as younger adults (Bahramali et al. 1999; Groth and Allen 2000; Verhaeghen and Cerella 2002; Madden et al. 2004; Ballesteros et al. 2008), yet other studies show they are more influenced by unattended stimuli (Andres et al. 2006; Yang and Hasher 2007), particularly cross-sensory stimuli (Alain and Woods 1999; Poliakoff et al. 2006).

Of particular relevance to the findings reported here are two recent studies, one imaging and one psychophysical. An imaging study investigating memory function in older adults observed that during a visual memory task, older adults showed greater auditory activation than younger adults during unsuccessful encoding (Stevens et al. 2008), suggesting that older adults were more distracted by background auditory noise than younger adults. In addition, a recent behavioral experiment from our laboratory indexed background processing during selective attention using integration of to-be-ignored cross-sensory stimuli (Hugenschmidt et al. 2009). In that study, it was observed that not only was older adults' processing of unattended stimuli increased during selective attention, but it was also increased in the divided attention referent condition. Selective attention attenuated the processing of unattended stimuli in older and younger adults, but did not compensate for the older participants' overall increase of background processing. This meant that even after equivalent attentional modulation, older adults processed more background sensory information than younger adults. The present study is concerned with investigating the neural underpinnings of enhanced processing of background stimuli in healthy older adults.

Several positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies indicate that the neural mechanism of cross-sensory attention is a reciprocal relationship between sensory modalities with slightly enhanced processing in the attended modality and suppressed processing, or deactivation, in the unattended modality (Roland 1982; Kawashima et al. 1995; Ghatan et al. 1998; Weissman et al. 2004; Johnson and Zatorre 2005; Mozolic et al. 2008b), similar to the “spotlight” of visual attention. That is, the relevant signal in the attended modality is increased and noise (irrelevant information) from an unattended modality is decreased. In general, the amount of suppression in the unattended modality is greater than the increase of activity in the attended modality, highlighting the importance of cross-sensory deactivations. Research thus far shows robust decreases in activity of auditory cortex during both visual stimulation with low attentional load (Laurienti et al. 2002) and attention alone in the absence of visual stimulation (Mozolic et al. 2008b), suggesting both bottom-up and top-down contributions to cross-sensory deactivations. The bulk of neuroimaging research on cross-sensory attention has focused on the relationship between the visual and auditory senses, partly due to the relative dominance of these senses and because of methodological difficulties in presenting olfactory, gustatory, and tactile stimuli in the scanner environment. Nevertheless, there is evidence that cross-sensory deactivations are a fundamental aspect of modality-specific attention regardless of the sensory modality (Kawashima et al. 1995).

The behavioral studies mentioned above suggest clear hypotheses for the effects of healthy aging on the neural mechanisms of cross modal attention. Older adults should be able to attentionally modulate processing in sensory cortices, but still show relatively increased processing of ignored stimuli when compared to younger adults. Another way to conceptualize this idea is that older adults show an increase in cross-sensory noise. Attention can be thought of as a mechanism to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the attended modality. If older adults process more ignored stimuli (noise) when they are attending, they may be able to effectively modulate sensory inputs with attention, yet still have a poorer overall SNR than younger adults. The ability to investigate this hypothesis with fMRI is limited by the fact that the signal is relative in nature. Areas of neural activity in fMRI paradigms are determined by comparing active and control conditions since absolute measures cannot be obtained (Ogawa et al. 1990; Kwong et al. 1992). This means that the difference of interest here, a baseline increase in sensory processing, would not be evident in a traditional fMRI paradigm as it would be present during both the task and referent conditions. In fact, results from a low level attentional task in our laboratory bear this out, as age had no differential effect on activity in unisensory cortices in older adults compared to baseline (Peiffer et al. 2007).

Quantitative perfusion imaging is similar to blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fMRI in that it uses the paramagnetic properties of blood to image neural activity through blood flow changes in the brain. Unlike fMRI, though, perfusion imaging yields quantitative maps of cerebral blood flow (CBF), meaning that comparison with a referent condition is not necessary (Buxton et al. 1998b; Wong et al. 1998b). Perfusion imaging has not supplanted traditional fMRI because as a dynamic measure it has lower signal and poorer time resolution. However, the technique has excellent signal as a steady-state technique that measures average blood flow over several minutes (Wang et al. 2003) in a manner conceptually similar to PET imaging. Therefore, the present study investigated the effects of aging on processing of background auditory stimuli by comparing average CBF during steady-state resting and visual conditions. It was hypothesized that older adults would show greater auditory activity at rest than younger adults (proportional to their own grey matter perfusion). It was further hypothesized that task-related attenuation of auditory activity during visual stimulation would be observed for both age groups due to cross-sensory suppression of activity. However, auditory activity was still expected to be greater in older adults secondary to changes in baseline processing.

In addition to auditory activity, the relationship between activity in auditory and visual cortices was of interest as a metric of cross-sensory noise. It was hypothesized that older adults would show reduced cross-sensory SNR assessed as the ratio of auditory to visual activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Data were collected on 20 young (mean age = 26.9 ± 5.8, 9 women) and 20 older (mean age = 73.3 ± 6.4, 11 women) volunteers. Data from one older participant were not included in the analysis as the normalized perfusion values for auditory cortex were greater than 3 standard deviations from the older adult mean. As this was a study of healthy aging, potential participants were excluded for a self-reported history or medications consistent with dementia, neurological disease, psychiatric disorders, stroke, head injury, or diabetes. Participants were also excluded for evidence of dementia, defined as a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score more than 2.5 standard deviations from their age and education adjusted mean (Bravo and Herbert 1997), or alcoholism as assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Bohn et al. 1995). Volunteers who reported a diagnosis of depression were included if they had been receiving treatment for at least 3 months and were currently non-symptomatic when assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Haringsma et al. 2004). Volunteers were required to have functional color vision as evidenced by a score of less than 7 on the Concise Edition of Ishihara's Test for Colour-blindness (Kanehara and Co., Tokyo, Japan), corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or better in both eyes measured with a modified Snell visual acuity exam, and no more than moderate hearing loss, defined as 50dB measured with a digital audiometer (Digital Recordings, Halifax, Nova Scotia). Participants provided informed consent. All study procedures were approved by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board for the protection of human subjects in research and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Behavioral study design

Data for this study were collected over three visits: a screening visit, a behavioral visit and an imaging visit. Several measures of cognitive function were collected during the behavioral visit, including a task indexing cross-sensory distraction, which was used in the current analysis. This paradigm is a modification of a visual task designed to look at the influence of perceptual load on distractor processing (Maylor and Lavie 1998). In this task, participants are presented with a circular array of letters that always includes either an X or an N and can range in size from one to six letters. Subjects are instructed to indicate with a button press whether an X or an N is present in the array. At the same time the set of letters is displayed, a distractor letter is presented to the left or right of the array. In the adaptation of the task used here, the distractor letter can be congruent with the target letter (e.g., target = X, distractor = X), incongruent (e.g., target = X, distractor = N) or neutral (e.g., target = X, distractor = T). In the cross-sensory version of this task adapted from Tellinguisen and Nowak (2003), the presentation of the target letter in the array remains the same, but the distractor is a spoken letter presented through speakers. In younger adults, increasing distraction was noted with increasing set size in the cross-sensory task (Tellinghuisen and Nowak 2003).

In this study, subjects began each trial with a delay that varied randomly between 0 and 300 ms, during which a grey fixation cross was displayed on a black background. The fixation cross remained displayed on the center of the screen throughout the experiment. The random delay was followed by a 200 ms presentation of the stimulus, a circular array of grey letters subtending 6 degrees presented on a black background. The array size randomly varied between 1, 2, 4 or 6 letters. A target (X or N) was always present in the array. X and N were presented equally often as targets and target position within the array on each trial was randomly ordered and counterbalanced across trial types. At the same time that the stimulus array was displayed, a spoken letter (N, X, T, L) was presented through speakers flanking the screen. Participants then had 3000 ms to respond with a button press to indicate whether the target was an X or N. Response button assignment was randomized across subjects so that half of the young and half of the older participants pressed the left hand button for the letter X. After the 3000 ms response period, participants were provided with feedback about the accuracy of their response in the form of a beep if their response was incorrect. Participants completed 3 blocks of 96 trials, for a total of 32 trials in each of 12 conditions (4 sets sizes × 3 distractor conditions). The behavioral cross-sensory distraction paradigm was completed in a sound and light attenuated booth (Whisper Room, Morristown, PA, USA). All stimuli were presented and reaction time and accuracy data collected using E-Prime stimulus presentation software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Reported reaction times are from correct responses only. Each participant's reaction time data were cleaned for outliers by removing responses that were more than 3 standard deviations from that participant's mean on the task.

The measure used for the analysis included here is the difference in reaction time between neutral and incongruent distractor trials at set size 6. It was hypothesized that distraction as evidenced by slower reaction times on incongruent trials would correlate with auditory cortical activity during the visual condition.

2.3 Imaging study design

In the course of the imaging visit, a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was collected, followed by two perfusion and three fMRI scans. The order of perfusion and fMRI scans was randomized across subjects, with the constraint that the two perfusion scans were completed together. Data from the perfusion portion of the imaging visit are reported here. During a resting state perfusion scan, participants viewed a grey fixation cross on a black background. During a visual steady-state perfusion scan they watched a color video clip with no sound. Edited video clips were extracted from the documentary Of Penguins and Men, a special feature describing the making of the film March of the Penguins (2005, Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.). Film clips were edited using Ulead VideoStudio software (www.ulead.com) and presented using Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, CA, USA; www.neurobs.com). Participants were told that they should carefully attend to the video as they would be given a quiz on its content following the scan. Following the imaging session, all participants completed a follow-up questionnaire where they provided subjective feedback about their alertness, described any strategies they used during scanning, and answered questions about the content of the videos they viewed. All stimuli were presented through MRI compatible goggles (Resonance Technology, Inc., Northridge, CA) with an integrated infrared eye tracker used to ensure that subjects kept their eyes open throughout the experiment.

2.4 MRI acquisition

All images were acquired in a 1.5T echo speed horizon LX General Electric Scanner with a neurovascular head coil (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). High resolution T1- weighted images were acquired with a multi-slice spoiled gradient inversion recovery (3DSPGR-IR) protocol with the following parameters: phase = 256, frequency = 192; 128 contiguous slices, 1.5 mm thick; in-plane resolution 0.938 × 0.938 mm; TE=1.9 ms; TI=600 ms.

Cerebral blood flow was measured with QUantitative Imaging of Perfusion using Single Subtraction with Thin Slice TI1 Periodic Saturation: QUIPSS II TIPS, also known as Q2TIPS (Luh et al. 1999) with Flow-sensitive Alternative Inversion Recovery (FAIR) encoding (Kim and Tsekos 1997). Images were acquired with a single shot gradient echo Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) sequence (Mansfield 1977). Blood was tagged using a C-shaped Frequency Offset Corrected Inversion (C-FOCI) pulse (β=1361, μ=6) (Ordidge et al. 1996) to improve perfusion sensitivity by minimizing slice imperfections (Frank et al. 1997; Yongbi et al. 1999). Very Selective Suppression (VSS) pulses (Tran et al. 2000) were applied every 25 msec between 800 ms (TI1) and 1200 msec (TI1s) to minimize the uncertainty of the transit time of the labeled blood to the imaging slice (Wong et al. 1998a). Three VSS pulses were also applied immediately before and after the inversion pulses to suppress tissue signal in the imaging plane. Immediately after the EPI 90 degree excitation RF pulse, a bipolar diffusion gradient with an equivalent b value of 5.25 mm2/sec was used to suppress intra-arterial spins (Yang et al. 1998). Additional parameters of interest for the Q2TIPS-FAIR-EPI sequence used in this experiment are as follows: TE = 30.4 msec, TR = 3000 sec, TI = 2000 msec, bandwidth = 62.5 kHz, flip angle = 90 degrees, field of view = 240 mm (frequency) × 240 mm (phase), and an acquisition matrix of 64 (frequency) × 40 (phase).

The total duration of the Q2TIPS-FAIR sequence was 8 minutes 36 seconds. The first 36 seconds were used to achieve steady state and consisted of a 6 second quiescent delay that ensured spins were at thermal equilibrium prior to scanning, followed by 8 volume acquisitions. After the initial 6 seconds, a single-shot EPI proton density (M0) image was acquired. The initial 36 seconds were followed by 82 alternating slice-selective and non-selective radiofrequency inversion pulses (label/control pairs). Twelve contiguous 8-mm thick slices were acquired inferior to superior and aligned parallel to the anterior commissure/posterior commissure (AC/PC) line. Slices were placed to ensure full coverage of the occipital cortex. For most subjects, there were 4 slices below and 8 slices above the AC/PC line.

2.5 Computation of cerebral blood flow

Perfusion data were preprocessed using SPM5 software (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London, UK, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) implemented in Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA) (Maldjian et al. 2008). The reconstructed control and label images were motion corrected separately with a six-parameter rigid body transformation. After motion correction, control/label images were pair-wise subtracted, yielding difference images. The difference images were averaged and quantitative perfusion maps were calculated from Equation 1:

| (1) |

In this equation, cerebral blood flow (CBF) is calculated where ΔM(TI2) is the mean difference in the signal intensity between the label and control images, α is tagging efficiency, TI1 is the time duration of the tagging bolus, TI2 is the inversion time of each slice, M0,blood is the equilibrium magnetization of blood, T1,blood is the longitudinal relaxation time of blood, and qp is a correction factor that accounts for the difference between the T1 of blood and the T1 of brain tissue (Wong et al. 1998a). For this study, the correction factor qp was assumed to be unity, which is a reasonable approximation when the T1 of blood and the T1 of brain tissue are similar. Based upon the literature the T1 of blood was assumed to be 1200ms at 1.5T (Simonetti et al. 1996). The inversion efficiency was measured to be 0.95 from prior experiments in our laboratory (data not shown). The mean signal of white matter (M0, white matter) was calculated from thresholded tissue maps and was used to approximate the M0,blood (Wong et al. 1998a). Tissue probability maps were created using an SPM99 automated segmentation of the T1-weighted anatomical scan. The high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was coregistered to the M0 image and this transformation was applied to the tissue probability maps. The coregistered white matter probability maps were thresholded at 81% probability to create a white matter mask. Absolute quantitative CBF maps (ml/100 g tissue/min) were calculated using equation 1 according to the General Kinetic Model (Buxton et al. 1998a).

2.6 Spatial normalization

Perfusion maps were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template using SPM5. As mentioned above, the M0 image collected at the beginning of each perfusion scan is single-shot EPI proton density image. As it is acquired as part of the perfusion sequence it is in the same space as the other perfusion images. The perfusion images cannot be directly normalized to standard space because the normalization procedure depends on the presence of an appropriate template image. Therefore, each subject's M0 image was first normalized to the SPM5 EPI template (Ashburner and Friston 2005) since the images have the same contrast. Then the quantitative perfusion images were then normalized by applying the parameters obtained from warping the M0 image to the EPI template. All the images were then smoothed with an 8×8×10 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

2.7 Data analysis

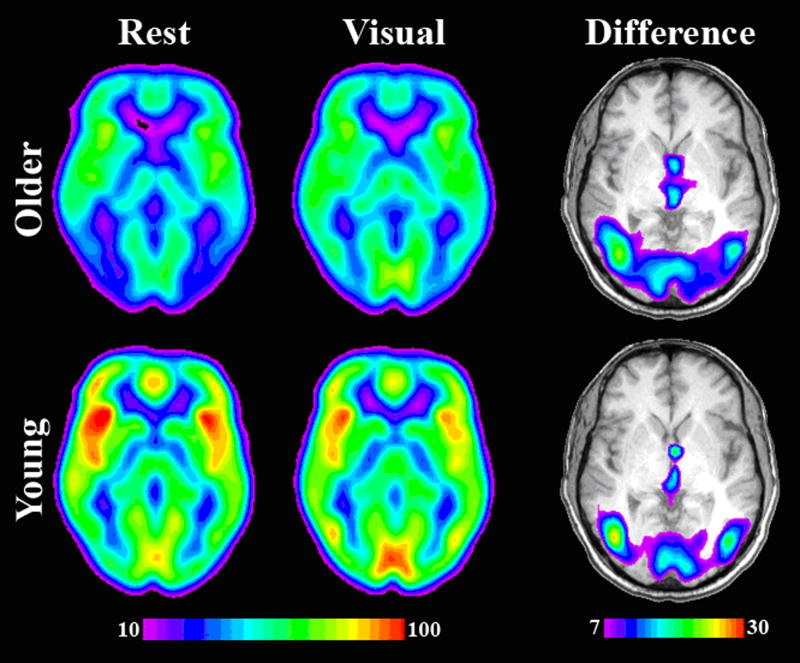

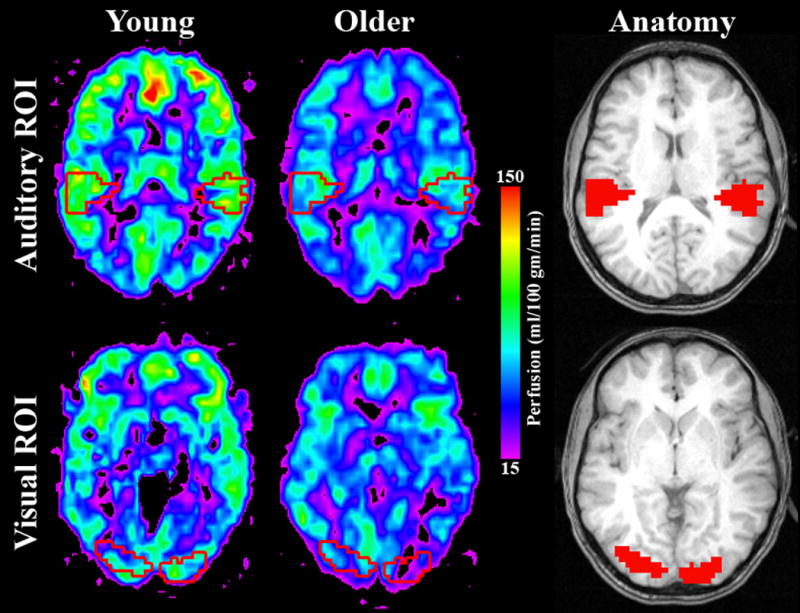

Regional CBF was evaluated as a marker of neuronal activity. Region of interest (ROI) analyses were completed to investigate a priori hypotheses. Two ROIs (Figure 1) were selected using Wake Forest University's Pickatlas tool (Maldjian et al. 2003) and assessed statistically using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Regions of visual- and auditory-responsive cortex were defined from previously published fMRI data on 19 healthy young subjects performing simple auditory and visual tasks (Peiffer et al. 2007). Both paradigms consisted of two runs of a block design task where subjects alternated 4 30s ON blocks with 4 30s OFF blocks where they viewed a grey fixation cross on a black background. In the visual task, participants viewed a 2Hz flashing checkerboard and were instructed to press a button when the checkerboard blurred. During the auditory task, participants viewed a grey fixation cross on a black background while hearing white noise bursts at 2Hz. They were instructed to press a button when they heard a tone embedded in the white noise. The auditory ROI was generated from the contrast image showing where the auditory task was greater than rest after correction for multiple comparisons at p < 0.05 using family-wise error (FWE). The visual ROI was generated in the same way for the visual task, with the exception that the threshold was more stringent (p < 0.01 using FWE) so that the visual and auditory ROIs would be similar in size. The ROIs generated for visual and auditory cortices were both bilateral and approximately the same size (visual left = 167 voxels, visual right = 189 voxels; auditory left = 160 voxels, auditory right = 164 voxels). The ROIs are illustrated in Figure 1 overlaid on an anatomical image as well as a representative perfusion image from a younger and older subject.

Figure 1. Visual and auditory ROIs illustrated on individual quantitative perfusion maps and an anatomical image.

The quantitative perfusion maps illustrate blood flow on a representative older and younger subject with the location of ROIs overlaid. ROIs are illustrated as red outlines on the perfusion maps and filled red regions on the anatomical images. All slices showing the visual ROI are at MNI z = 0 and all slices showing the auditory ROI are at MNI z = 17.

It is important to evaluate the CBF measures relative to the whole brain mean as previous studies have shown an overall decrease in cortical perfusion in older adults (Pantano et al. 1984; Marchal et al. 1992; Bentourkia et al. 2000; Meltzer et al. 2000; Van Laere and Dierckx 2001; Takahashi et al. 2005). This difference is replicated in the present study and is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows voxel-wise average CBF maps for younger and older adults. Each subject's ROI activity was normalized by dividing the average ROI CBF value by their average grey matter CBF value to account for global changes in CBF. Mean gray matter CBF values were calculated by averaging the perfusion values from all the voxels contained in a gray matter mask determined from the coregistered tissue probability map by thresholding at 51% probability. ROIs computed on the resting data were normalized with average grey matter perfusion during rest, and those from the visual condition were normalized by average grey matter perfusion during the visual condition. These normalized CBF values for each ROI during the rest and visual engagement conditions were compared between age groups using a 2 Age × 2 Condition repeated measures ANOVA. Average whole-brain grey matter CBF values are also reported.

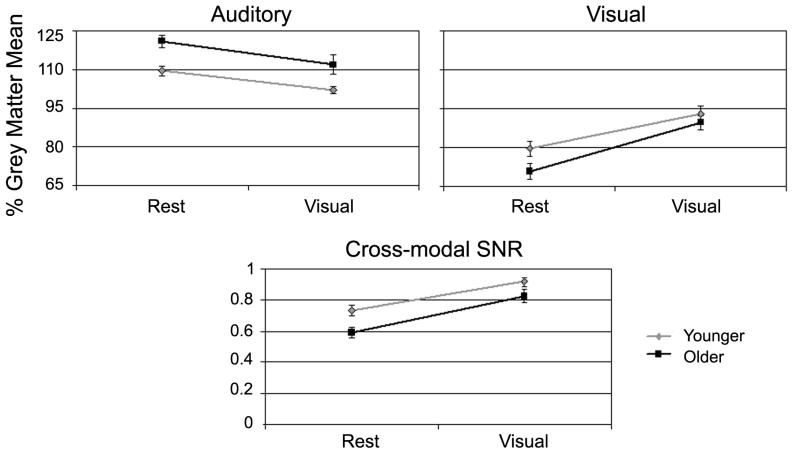

Figure 2. Average quantitative cerebral blood flow maps visual and resting states and the difference between them.

These images illustrate several points. First, global decreases in cerebral perfusion are clearly evident in older adults in both the resting and visual condition. Secondly, the difference images (visual – rest) show the expected increase in visual cortical activity in both age groups. Two axial slices are shown for each subject population. All images are located at MNI z = 0.

3. Results

Overall grey matter perfusion during resting state was observed to be significantly greater in younger adults (mean = 66.972 ± 14.4) than older adults (mean = 48.95 ± 12.3) using a two-sample t-test assuming unequal variances (t = 4.26, p < 0.01), replicating findings from previous studies. Average grey matter perfusion was also greater in younger adults (mean = 68.81 ± 16.1) than older adults (mean = 52.98 ± 13.2) during the steady-state visual condition (t = 3.40, p < 0.01). To control for these global differences in the regional analyses, each subject's data were normalized to their corresponding global gray matter perfusion as described in the Methods section. Figure 2 illustrates average CBF maps for visual and rest conditions for younger and older adults, along with a subtraction of the two maps showing the expected outcome of increased activity in visual regions during the visual task.

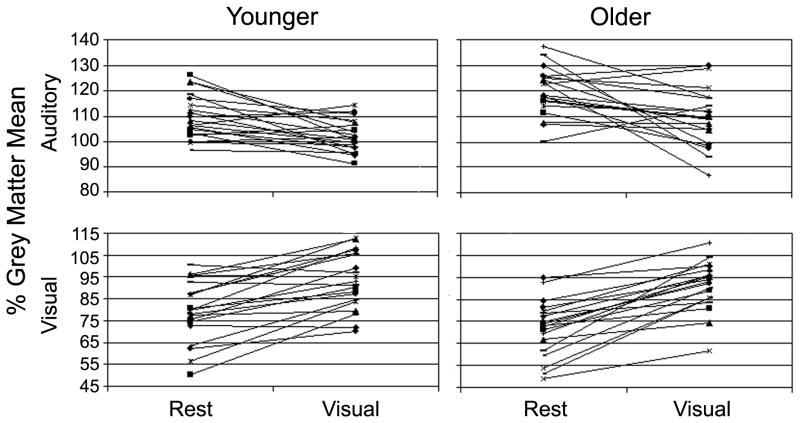

A 2 Age × 2 Condition repeated measures ANOVA was performed on average CBF in the auditory cortex ROI. Significant main effects were observed for both Age (F (1, 37) = 15.98, p < 0.001) and Condition (F (1, 37) = 22.17, p < 0.001). Older adults had higher levels of normalized perfusion in auditory cortex in both conditions than younger adults, and both age groups had greater activity of auditory cortex in the resting condition than the active condition (Figure 3A). No interaction of Age and Condition was observed (F (1, 37) = 0.64, p = 0.43), suggesting that both study populations effectively suppressed activity in auditory cortex during visual engagement. Differences in auditory activity between age groups at rest were directly tested using a two-sample t-test assuming unequal variances, as this difference was an a priori hypothesis. The results of the t-test supported the observation from the main effect of the ANOVA that older adults had significantly greater auditory activity during visual fixation (t = -3.52, p < 0.01). Line graphs of average ROI activity for individual younger and older subjects are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Steady-state activity for rest and visual engagement.

Results from ROI analysis in older adults are shown in black and younger adults in grey. (A) Normalized average CBF values within the auditory ROI show significantly greater activity in older adults than younger adults during the rest condition. Engagement in a visual task reduced perfusion for both groups, but average values were still greater in older adults. (B) Normalized average CBF values within the visual ROI showed greater activity in younger adults than older adults at rest. Both age groups show increases in activity in response to the visual stimulus. The older adults have a slightly larger increase than younger adults, although the interaction between age and condition did not reach significance. (C) Cross-modal SNR was calculated by taking a ratio of the visual to auditory ROIs. Younger adults have significantly higher SNR during both resting and visual stimulation conditions. Error bars show standard error of the mean.

Figure 4.

Similarities and differences in individual performance can be observed on the graph. Overall, average auditory CBF values for older adults are shifted higher than younger adults. As is observed in many studies of aging, some in the older population seem to perform similarly to younger adults while others are more different.

Average CBF in the visual ROI was compared using a 2 Age × 2 Condition repeated measures ANOVA. The main effect of Condition (F (1, 37) = 94.3, p < 0.001) was significant, reflecting the fact that visual activity was greater during the visual condition than rest. However, the main effect of Age did not reach significance (F (1, 37) = 1.73, p = 0.19). There was a trend toward significance in the interaction between Age and Condition (F (1, 37) = 2.95, p > 0.10), reflecting that the older adults showed a slightly larger increase between rest and visual conditions than younger adults (Figure 3B). These results demonstrate that both older and younger participants showed significantly increased activity in visual cortex during the visual condition. Older adults showed slightly less activity at rest and a slightly greater increase between rest and visual conditions, but these differences were not significant. Again, plots of individual ROI values are shown in Figure 4.

As both of the study conditions were visual in nature, a low level visual task of fixation and visual engagement during the viewing of a movie, no auditory information was task relevant. Therefore, all auditory processing can be considered “noise” in relation to the visual tasks. The proportion of visual to auditory perfusion was evaluated as a measure of the cross-sensory signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). A 2 Age × 2 Condition repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate the ratios. Significant main effects were again observed for both Age (F (1, 37) = 5.50, p < 0.03) and Condition (F (1, 37) = 89.10, p < 0.001), reflecting the fact that older adults had a lower SNR than their younger counterparts in both conditions, and that SNR was higher during the active task for both age groups (Fig. 4.2C). The interaction of Age and Condition did not reach significance (F (1, 37) = 1.69, p = 0.20). Thus, both groups effectively increased the SNR during visual processing but the older adults had a lower SNR in both conditions.

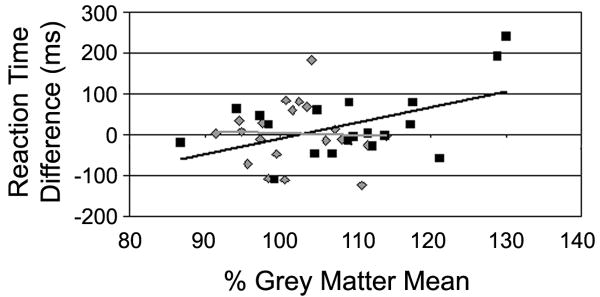

The general linear model was then used to evaluate the relationship between a behavioral measure of cross-sensory distraction and auditory activity during the active task (Figure 5). A significant positive correlation was observed between auditory activity and cross-sensory distraction for older and younger adults together (F (1, 27) = 5.09, p < 0.04, r = 0.35). However, when the correlation was performed separately on older and younger groups, a significant correlation between distraction and auditory activity was only observed for older participants (F (1,18) = 6.18, p < 0.03, r = 0.52) and not for younger participants (F (1, 19) = 0.02, p = 0.88, r = 0.04), indicating that the relationship of cross-sensory distraction with auditory activity may change with age.

Figure 5. Relationship between behavioral cross-modal distraction and auditory activity during the visual task.

Younger adults are shown as grey diamonds and older adults as black squares, with regression lines shown in the same colors (the younger regression line almost overlays the abscissa). Older adults showed a significant relationship between increased distraction (larger reaction time difference) and activity of auditory cortex during the visual task, when activity is decreased relative to rest in both younger and older adults. Younger r = 0.04, Older r = 0.52.

4. Discussion

As hypothesized, older adults showed greater auditory activity than younger adults to background auditory stimuli during resting state and during a visual steady-state condition. In addition, auditory activity was attenuated when participants viewed an engaging visual stimulus, but the reduction in auditory activity did not vary by age group. Older adults also evidenced a decrease in cross-sensory SNR in both conditions, reflecting that the relationship between activity in visual and auditory cortices changed with age. Older adults showed a slightly greater increase in visual activity between rest and active conditions, but this did not compensate fully for the age-related increase in auditory response to background noise. Furthermore, auditory activity during the active visual task was correlated with a behavioral measure of cross-sensory distraction in older adults.

These important findings suggest a neural mechanism for the behavioral observation that older adults are more distracted by background auditory stimuli than younger adults (Alain and Woods 1999; Stevens et al. 2008), in spite of the fact that they are able to successfully instantiate selective attention (Bahramali et al. 1999; Groth and Allen 2000; Verhaeghen and Cerella 2002; Madden et al. 2004; Ballesteros et al. 2008). As mentioned in the introduction, a previous study from our laboratory (Hugenschmidt et al. 2009) noted that even after older adults suppressed background stimuli as much as younger adults, the background stimuli still elicited responses in the form of multisensory interactions. These findings suggest that increased distractibility is not due to a failure in top-down attentional mechanisms. Older adults can successfully modulate sensory activity with attention, as observed in the perfusion data presented here, suggesting that increased distractibility may be driven by a bottom-up rather than top-down process. In addition, a recent fMRI study showed enhanced auditory activity in older adults during unsuccessful encoding in a visual memory task (Stevens et al. 2008), indicating that increased background processing of auditory stimuli during a visual task decreases task performance. The results of the present study add to these findings by demonstrating that older adults show increased activity in auditory cortex at rest. Auditory activity is suppressed by engagement in a visual task, as would be expected from previous research on cross-sensory deactivations (Kawashima et al. 1995; Laurienti et al. 2002; Johnson and Zatorre 2005; Mozolic et al. 2008a), but older adults continue to show greater auditory activity than younger adults. This means that the shift in auditory processing observed during visual tasks may actually stem from changes that are present at rest.

The results of this study are straightforward regarding the processing of background auditory stimuli during resting state and an engaging visual task. However, it is not clear if the reverse relationship is true, or if the findings will generalize to other pairings of cross-sensory stimuli, for instance vision and touch. Most studies that have investigated the effects of unattended or distractor stimuli in aging have either used unimodal paradigms (Yang and Hasher 2007; Healey et al. 2008) or examined the effects of auditory stimuli on visual processing (Alain and Woods 1999; Fabiani et al. 2006). The idea that auditory stimuli may be particularly potent distractors (Parmentier 2008) has some ecological validity. It is generally accepted that humans are visually dominant animals and that we negotiate our world visually. However, the visual system does not allow monitoring of all regions of the environment. In contrast, the auditory system provides lower spatial resolution, but allows 360 degree monitoring of the world. In this way, the auditory system may act preferentially to orient the visual modality. However, results from unimodal visual studies (Rowe et al. 2006; Yang and Hasher 2007; Healey et al. 2008) do show enhanced processing of background stimuli in older adults, which indicates that increased baseline processing of sensory stimuli as a source of distraction may be a general finding across modalities. Future research will be needed to resolve this question.

The study reported here relied on warping all participants' brains into a common space. In this case, the template used was the MNI template, a healthy young adult brain. Adequate normalization is a concern in any study comparing older and younger adults, as the atrophy in older brains means they must undergo more warping than younger adults in order to match a young adult template. This raises a potential concern that differences in perfusion in younger and older adults might be due to poor normalization in the regions of interest, where reduced activity is observed in older adults because they have less grey matter [e.g., (Sandstrom et al. 2006)]. Indeed, previous research on the effects of aging on grey matter volume has observed atrophy in temporal cortex/Sylvian fissure (Good et al. 2001; Sowell et al. 2003; Tisserand et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2007), although longitudinal studies suggest primary sensory cortices may show less atrophy than frontal and parietal regions (Resnick et al. 2003; Raz et al. 2005). However, warping failure in the auditory cortex would cause an underestimation of the auditory perfusion signal, meaning that if anything, normalization concerns would result in an underestimation of the increased auditory signal in older adults.

One potential caveat in interpreting this study is the use of cross-sensory SNR as a measure. To our knowledge, a ratio of sensory cortical activity has not been used before. Directly comparing activity in two different cortices would be uninterpretable, as there is no reason to assume that the relationships between cortical activity and perception are equivalent between modalities. However, comparing the ratio of activity across tasks and age groups reveals meaningful information about the relationship between the auditory and visual modalities. Prior research on cross-sensory attention makes a reliable prediction that during visual stimulation relative to eyes open fixation activity in the visual cortex should increase and activity in the auditory cortex should decrease, and indeed, this is the pattern that was observed. The important finding is that this metric of cross-sensory noise exhibits reductions during visual tasks in both age groups but that the older adults have reduced SNR across both study conditions.

In addition, the older subjects in this experiment are very healthy, with good sensory functioning and low prevalence of disease. As such, they are part of a population considered to be successful agers, and the findings from this study may not be representative of the entire spectrum of aging. However, there is evidence that older adults with Alzheimer's disease show impairments in their ability to suppress auditory cortex during a visual task (Drzezga et al. 2005), suggesting that similar processes may be at work in aging diseased populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Debra Hege for her invaluable assistance. Research support was provided by NIH#NS042658, NIH#AG030838-01A1, the Roena Kulynych Memory and Cognition Research Center, and the Wake Forest University GCRC #RR07122.

Reference List

- Alain C, Woods DL. Age-related changes in processing auditory stimuli during visual attention: evidence for deficits in inhibitory control and sensory memory. Psychol Aging. 1999;14:507–519. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.3.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres P, Parmentier FB, Escera C. The effect of age on involuntary capture of attention by irrelevant sounds: a test of the frontal hypothesis of aging. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2564–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahramali H, Gordon E, Lagopoulos J, Lim CL, Li W, Leslie J, Wright J. The effects of age on late components of the ERP and reaction time. Exp Aging Res. 1999;25:69–80. doi: 10.1080/036107399244147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros S, Reales JM, Mayas J, Heller MA. Selective attention modulates visual and haptic repetition priming: effects in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Exp Brain Res. 2008;189:473–483. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentourkia M, Bol A, Ivanoiu A, Labar D, Sibomana M, Coppens A, Michel C, Cosnard G, De Volder AG. Comparison of regional cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in the normal brain: effect of aging. J Neurol Sci. 2000;181:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The acohol use disorders identification test (audit): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:423. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo G, Herbert R. Age- and education-specific reference values for the Mini-Mental and Modified Mini-Mental State Examinations derived from a non-demented elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;12:1008–1018. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199710)12:10<1008::aid-gps676>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998a;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998b;40:383–396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzezga A, Grimmer T, Peller M, Wermke M, Siebner H, Rauschecker JP, Schwaiger M, Kurz A. Impaired cross-modal inhibition in Alzheimer disease. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiani M, Low KA, Wee E, Sable JJ, Gratton G. Reduced suppression or labile memory? Mechanisms of inefficient filtering of irrelevant information in older adults. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:637–650. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LR, Wong EC, Buxton RB. Slice profile effects in adiabatic inversion: Application to multislice perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:558–564. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatan PH, Hsieh JC, Petersson KM, Stone-Elander S, Ingvar M. Coexistence of attention-based facilitation and inhibition in the human cortex. Neuroimage. 1998;7:23–29. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Johnsrude IS, Ashburner J, Henson RNA, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RSJ. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. NeuroImage. 2001;14:21–36. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth KE, Allen PA. Visual attention and aging. Front Biosci. 2000;5:D284–297. doi: 10.2741/groth. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haringsma R, Engels GI, Beekman AT, Spinhoven P. The criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of self-referred elders with depressive symptomatology. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:558–563. doi: 10.1002/gps.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey MK, Campbell KL, Hasher L. Cognitive aging and increased distractibility: costs and potential benefits. Prog Brain Res. 2008;169:353–363. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugenschmidt CE, Mozolic JL, Laurienti PJ. Suppression of multisensory integration by modality-specific attention in aging. Neuroreport. 2009;20:349–353. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328323ab07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA, Zatorre RJ. Attention to simultaneous unrelated auditory and visual events: behavioral and neural correlates. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1609–1620. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima R, O'Sullivan BT, Roland PE. Positron-emission tomography studies of cross-modality inhibition in selective attentional tasks: closing the “mind's eye”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5969–5972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Tsekos NV. Perfusion imaging by a flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional brain imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:425–435. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, Goldberg IE, Weisskoff RM, Poncelet BP, Kennedy DN, Hoppel BE, Cohen MS, Turner R, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH, Wallace MT, Yen YF, Field AS, Stein BE. Deactivation of sensory-specific cortex by cross-modal stimuli. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:420–429. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luh WM, Wong EC, Bandettini PA, Hyde JS. QUIPSS II with thin-slice TI1 periodic saturation: a method for improving accuracy of quantitative perfusion imaging using pulsed arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:1246–1254. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199906)41:6<1246::aid-mrm22>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DJ, Whiting WL, Cabeza R, Huettel SA. Age-related preservation of top-down attentional guidance during visual search. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:304–309. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH, Kraft RA. Clinical implementation of spin-tag perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:403–406. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31816b650b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield P. Multi-Planar Image-Formation Using Nmr Spin Echoes. J Phys C Solid State Phys. 1977;10:L55–L58. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal G, Rioux P, Petit-Taboue MC, Sette G, Travere JM, Le Poec C, Courtheoux P, Derlon JM, Baron JC. Regional cerebral oxygen consumption, blood flow, and blood volume in healthy human aging. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1013–1020. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530340029014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylor EA, Lavie N. The influence of perceptual load on age differences in selective attention. Psychol Aging. 1998;13:563–573. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer CC, Cantwell MN, Greer PJ, Ben-Eliezer D, Smith G, Frank G, Kaye WH, Houck PR, Price JC. Does cerebral blood flow decline in healthy aging? A PET study with partial-volume correction. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1842–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozolic JL, Hugenschmidt CE, Peiffer AM, Laurienti PJ. Modality-specific selective attention attenuates multisensory integration. Exp Brain Res. 2008a;184:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozolic JL, Joyner D, Hugenschmidt CE, Peiffer AM, Kraft RA, Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ. Cross-modal deactivations during modality-specific selective attention. BMC Neurol. 2008b;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Lee TM, Kay AR, Tank DW. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9868–9872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordidge RJ, Wylezinska M, Hugg JW, Butterworth E, Franconi F. Frequency offset corrected inversion (FOCI) pulses for use in localized spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:562–566. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantano P, Baron JC, Lebrun-Grandie P, Duquesnoy N, Bousser MG, Comar D. Regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in human aging. Stroke. 1984;15:635–641. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier FB. Towards a cognitive model of distraction by auditory novelty: The role of involuntary attention capture and semantic processing. Cognition. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer AM, Hugenschmidt CE, Maldjian JA, Casanova R, Srikanth R, Hayasaka S, Burdette JH, Kraft RA, Laurienti PJ. Aging and the interaction of sensory cortical function and structure. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliakoff E, Ashworth S, Lowe C, Spence C. Vision and touch in ageing: crossmodal selective attention and visuotactile spatial interactions. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, Zonderman AB, Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3295–3301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland PE. Cortical regulation of selective attention in man. A regional cerebral blood flow study. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1982;48:1059–1078. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.5.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe G, Valderrama S, Hasher L, Lenartowicz A. Attentional disregulation: a benefit for implicit memory. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:826–830. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom CK, Krishnan S, Slavin MJ, Tran TTT, Doraiswamy PM, Petrella JR. Hippocampal atrophy confounds temlate-based functional MR imaging measures of hippocampal activation in patients with mild cognitive impairment. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2006;27:1622–1627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti OP, Finn JP, White RD, Laub G, Henry DA. “Black blood” T2-weighted inversion-recovery MR imaging of the heart. Radiology. 1996;199:49–57. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Chebrolu H, Wekstein DR, Schmitt FA, Markesbery WR. Age and gender effects on human brain anatomy: a voxel-based morphometric study in healthy elderly. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens WD, Hasher L, Chiew KS, Grady CL. A neural mechanism underlying memory failure in older adults. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12820–12824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2622-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamaguchi S, Kobayashi S, Yamamoto Y. Effects of aging on regional cerebral blood flow assessed by using technetium Tc 99m hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime single-photon emission tomography with 3D stereotactic surface projection analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2005–2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellinghuisen DJ, Nowak EJ. The inability to ignore auditory distractors as a function of visual task perceptual load. Percept Psychophys. 2003;65:817–828. doi: 10.3758/bf03194817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisserand DJ, van Boxtel MP, Pruessner JC, Hofman P, Evans AC, Jolles J. A voxel-based morphometric study to determine individual differences in gray matter density associated with age and cognitive change over time. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:966–973. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TKC, Vigneron DB, Sailasuta N, Tropp J, Le Roux P, Kurhanewicz J, Nelson S, Hurd R. Very selective suppression pulses for clinical MRSI studies of brain and prostate cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:23–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<23::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere KJ, Dierckx RA. Brain perfusion SPECT: age- and sex-related effects correlated with voxel-based morphometric findings in healthy adults. Radiology. 2001;221:810–817. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213010295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Cerella J. Aging, executive control, and attention: a review of meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Aguirre GK, Kimberg DY, Roc AC, Li L, Detre JA. Arterial spin labeling perfusion fMRI with very low task frequency. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:796–802. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DH, Warner LM, Woldorff MG. The neural mechanisms for minimizing cross-modal distraction. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10941–10949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3669-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Quantitative imaging of perfusion using a single subtraction (QUIPSS and QUIPSS II) Magn Reson Med. 1998a;39:702–708. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Quantitative imaging of perfusion using a single subtraction (QUIPSS and QUIPSS II) Magn Reson Med. 1998b;39:702–708. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Hasher L. The enhanced effects of pictorial distraction in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:P230–233. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.p230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Frank JA, Hou L, Ye FQ, McLaughlin AC, Duyn JH. Multislice imaging of quantitative cerebral perfusion with pulsed arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:825–832. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yongbi MN, Yang Y, Frank JA, Duyn JH. Multislice perfusion imaging in human brain using the C-FOCI inversion pulse: comparison with hyperbolic secant. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1098–1105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1098::aid-mrm14>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]