Abstract

The shift toward viewing patients as active consumers of health information raises questions about whether individuals respond to health news by seeking additional information. This study examines the relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking using a national survey of adults aged 18 years and older. A Lexis-Nexis database search term was used to identify Associated Press (AP) news articles about cancer released between October 21, 2002, and April 13, 2003. We merged these data to the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), a telephone survey of 6,369 adults, by date of interview. Logistic regression models assessed the relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking. Overall, we observed a marginally significant positive relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking (p < 0.07). Interaction terms revealed that the relationship was apparent only among respondents who paid close attention to health news (p < 0.01) and among those with a family history of cancer (p < 0.05). Results suggest that a notable segment of the population actively responds to periods of elevated cancer news coverage by seeking additional information, but they raise concerns about the potential for widened gaps in cancer knowledge and behavior between large segments of the population in the future.

The growing emphasis in clinical medicine on patients participating more actively in making health care decisions, combined with rapid growth in the availability of health information, creates potential for widespread use of publicly available information in medical decisions (Frosch & Kaplan, 1999). In light of these systemic changes, it is vitally important to understand how health consumers navigate the health information environment. Information seeking is increasingly viewed as an important mediator between health information in the media and subsequent health knowledge and behaviors (Griffin, Dunwoody, & Neuwirth, 1999; Johnson, 1997; Niederdeppe et al., 2007). Optimistic views suggest that many search for additional health information when exposed to health news (Campion, 2004; Nelson et al., 2004), but the extent to which this occurs remains largely unknown. This article examines the relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking using data from a national survey.

News Coverage and Health Behavior

Health news coverage has contributed to notable changes in preventive behavior. Lagged time-trend analyses link news coverage to decreases in the administration of aspirin to children and subsequent development of Reye’s syndrome (Soumerai, Ross-Degnan, & Kahn, 2002), reductions in youth marijuana use (Stryker, 2003), increased smoking cessation (Pierce & Gilpin, 2001), decreases in youth cocaine use (Fan & Holway, 1994), reductions in HIV infection in gay men (Fan, 2002), reduced youth binge drinking (Yanovitzky & Stryker, 2001), increased mammography use (Yanovitzky & Blitz, 2000), and lowered levels of drunk driving (Yanovitzky & Bennett, 1999). In most of these cases, changes in behavior trends occurred in the wake of massive publicity about the benefits of performing preventive behaviors to reduce risk of disease.

But important unanswered questions about the effects of news media coverage on health behavior remain. First, each of the aforementioned studies explores news coverage effects on aggregate trends in health behavior, which does not address which population segments are influenced by health news coverage. Second, most of the aforementioned studies focus on health behaviors with strong scientific evidence supporting specific behaviors to prevent disease (e.g., National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA], 2004; Pinsky, Hurwitz, Schonberger, & Gunn, 1988; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services[USDHHS], 2001; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2002a;U.S. Surgeon General [USSG], 1990, 2004). The strength of evidence supporting these behaviors has produced consistent public health recommendations. It remains unclear how individuals respond to news coverage of diseases characterized by ambiguity about effective prevention and treatment.

There is a growing recognition among medical practitioners about high levels of scientific uncertainty regarding effective preventive measures for cancers (Kaplan & Frosch, 2005). Scientific evidence supporting effective preventive behaviors for most cancers is weak (Taubes, 1995), and the relative value of some screening tests is uncertain (American Urological Association [AUA], 2000; National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2003; Smith, Cokkinides, & Eyre, 2005; USPSTF, 2002b, 2002c). Many treatment options are available for several cancers with little agreement about which are best at various stages of disease (Middleton et al., 1995; National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], 2004).

News Coverage About Cancer

The uncertainty of much cancer information highlights the need to understand how individuals acquire and make sense of new cancer information. The news media are a primary source of new health information for physicians and the lay public alike (e.g., Niederdeppe et al., 2007; Phillips, Kanter, Bednarczyk, & Tastad, 1991; Yeaton, Smith, & Rogers, 1990). While widespread critiques of the quality of cancer news coverage abound (e.g., Freimuth, Greenberg, DeWitt, & Romano, 1984), factual disagreements between published scientific results and news reporting of them are rare (Bubela & Caulfield, 2004; Condit, 2004; Moyer, Greener, Beauvais, & Salovey, 1994). Most complaints about health news reporting are instead rooted in the conflict between journalistic and scientific norms (Entwistle, 1995; Ryan, 1979; Stryker, 2002). Journalists compete for limited newspaper space, resulting in efforts to enhance their stories by adding personal anecdotes or simplified results (Condit, 2004; Stryker, 2002). In light of these considerations, cancer news coverage might be characterized best as incomplete rather than inaccurate. The public nevertheless hears about new information about cancer through the news media (Niederdeppe et al., 2007) and is expected to make sense of this information (Sharf & Street, 1997; Stewart et al., 1995). Combined, these factors underscore the importance of information seeking in response to cancer news.

Information Seeking as Outcome

Recent years have witnessed increased interest in the dynamics of health information seeking (e.g., Brashers, Goldsmith, & Hsieh, 2002), particularly in the context of cancer (e.g., Johnson, 1997). Theories of health information acquisition consider information seeking as an important mediator between a stimulating event and subsequent behavior initiation or change (e.g., Griffin et al., 1999; Johnson, 1997). Individuals who seek health information report that information to be highly influential on subsequent health behavior decisions (Fox & Ranie, 2002; Freimuth, Stein, & Kean, 1989; Niederdeppe et al., 2007). Surveys document positive associations between health information seeking and both preventive behavior and screening test uptake (e.g., Dutta-Bergman, 2005; Knaus, Pinkleton, & Austin, 2000; Rakowski et al., 1990). Individuals who seek cancer information are more likely to hold accurate knowledge about cancer, engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors, and undergo cancer screening tests at recommended intervals (Shim, Kelly, & Hornik, 2006). These findings suggest that a greater understanding of the factors that promote information seeking could have favorable implications for efforts to change health behavior.

Study Hypotheses

Several studies demonstrate the effects of major celebrity news events on health information seeking, including Magic Johnson’s HIV status disclosure (Casey et al., 2003), Katie Couric’s colorectal cancer awareness campaign (Cram et al., 2003), and Nancy Reagan’s breast cancer diagnosis (Stoddard, Zapka, Schoenfeld, & Costanza, 1990). Far less is known about the effects of more routine news coverage about cancer. While major news events may raise awareness of the causes and treatments for particular cancers, thousands of news stories documenting new scientific evidence about cancer causes and treatments are published every year (Freimuth et al., 1984). The effects of these routine news stories on cancer information seeking remain largely unknown. Nevertheless, in the context of major news event effects on seeking, we propose the following:

H1: Controlling for major celebrity news events, individuals will report higher levels of cancer information seeking during periods of higher cancer news coverage.

Information-seeking models place a heavy emphasis on information access and use information access variables as key predictors of information seeking (e.g., Griffin et al., 1999; Johnson, 1997). Information-seeking studies cite news media use as a primary predictor of seeking behavior (e.g., Dutta-Bergman, 2005). Many argue, however, that long-term information acquisition is contingent on exposure and paying sufficient attention to process and store the message (Chaffee & Schleuder, 1986; Chaiken, 1987; McGuire, 2001; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Slater & Rasinski, 2005). News attention measures also account for more variance in knowledge (Romantan, Hornik, Weiner, Price, Cappella, & Viswanath, 2005) and risk judgments (Slater & Rasinski, 2005) than general news media use measures. These results suggest that health news attention measures should be particularly likely to moderate the relationship between cancer news and information seeking.

H2: The positive relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking will be stronger among respondents with greater attention to health news.

Individuals with cancer history (through either a personal or family member diagnosis) are far more likely to seek cancer information than those without such a history (e.g., Freimuth et al., 1989; Johnson, 1997). Personal experience with cancer is also an integral part of health information-seeking models (Griffin et al., 1999; Johnson, 1997). Hence, it is reasonable to suggest that individuals with a personal or family cancer history also should be more likely than others to respond to cancer news by seeking information.

H3: The positive relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking will be stronger among respondents with a family cancer history.

H4: The positive relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking will be stronger among respondents with a personal cancer history.

Methods

We tested study hypotheses by combining two sources of data. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) is a representative national survey conducted by the NCI examining the American public’s use of cancer-related information. We merged HINTS with data describing AP news coverage of cancer during the time period the first HINTS survey was conducted (October 21, 2002, through April 13, 2003).

Identification of Cancer News Articles

The AP is a wire service that is used by more than 85% of U.S. newspapers (Fan & Tims, 1989; Watt, Mazza, & Snyder, 1993) and is a reasonable proxy for broader media coverage of news topics (Fan, 1988; Romantan, 2004). The Lexis-Nexis database was used to search for cancer AP articles. We first examined AP coverage of cancer during time periods outside of the survey data collection period, with the ultimate goal of developing a reliable, replicable, automated search term closely following procedures described by Stryker, Wray, Hornik, and Yanovitzky (2006). We retrieved all AP articles for seven randomly selected days between May 2003 and October 2005 that contained the word “cancer,” or a variety of cancer synonyms, anywhere in the headline or text (the “calibration sample”; see Appendix A). We defined cancer news as stories that focused on prevention, screening, treatment, epidemiological findings, or stories from cancer patients and survivors. Using these criteria we identified relevant stories from the larger pool of articles containing “cancer” or cancer synonyms. Two independent coders were consistent in selecting relevant articles from a random subset of 236 stories (κ = 0.95).

Next we sought to create a detailed search term that would automate the retrieval of relevant articles. We iteratively tested our search term on 30 randomly chosen days between 2003 and 2005 (the “validation samples”). After the second iteration of this process, we achieved recall of 0.91 (95% CI 0.86–0.96) and precision of 0.84 (95%CI 0.74–0.94; Salton & McGill, 1983; Stryker et al., 2006). These values indicate that the final search term (Appendix B) captured 91% of all relevant articles identified by hand coding, while 84% of the articles captured by the computer were deemed relevant by human coders. We applied this search term to the time period during which survey data were collected (including the week before the first interview, from October 21, 2002 to April 13, 2003), yielding a total of 250 articles.

The identified stories covered a wide range of cancer news, including reports on major celebrity cancer events, inspirational stories about public figures who have overcome cancer diagnoses, cancer epidemiology, treatment development, and cancer risk quantification. For example, the sample included reports of Senator John Kerry’s treatment for prostate cancer and inspirational stories about Lance Armstrong being named the AP Athlete of the Year after being successfully treated for testicular cancer and winning the Tour de France. Other stories discussed attempts to alter a smallpox vaccine to attack cancer cells, the development of a formula to calculate lung cancer risk, and the identification of a new blood marker for colon cancer.

Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Data Collection Procedures

We merged AP news coverage data to the HINTS based on the date of interview. HINTS used random digit dialing (RDD) to recruit Americans aged 18 years or older to participate in a telephone survey between October 2002 and April 2003. The survey achieved a 34.5% response rate (55.0% household screening rate multiplied by 62.8% sampled person participation rate), resulting in a final sample of 6,369 respondents. Since the data are publicly available, the analysis met eligibility criteria for Institutional Review Board (IRB) review exemption.

HINTS purposely oversampled Hispanics and African Americans to enhance minority representation. The unweighted HINTS sample contained a larger percentage of females (60.4%) than males, with a mean age of 47.8 years (SD = 17.42). Most participants without missing values described themselves as Caucasian (70.5%), with 11.8% African American, 12.6% Hispanic, and 5.1% of another race/ethnicity. To account for the survey’s complex sample design and to create estimates generalizable to the national population of adults aged 18 and older, all subsequent study analyses (and all reported below) were conducted with replicate weights and jackknife standard errors using STATA’s “svy jackknife” command. Details about the sampling strategy and weighting procedures are published elsewhere (Nelson et al., 2004).

Dependent Variable: Cancer Information Seeking in the Past Week

HINTS asked respondents, “Have you ever looked for information about cancer from any source?” Participants who responded in the affirmative were asked, “About how long ago was that?” Overall, nearly half (44.9%) of the weighted sample reported having ever looked for information about cancer. We focused on whether an individual sought information within a week of their interview (5.0%; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Weighted variable distributions

| Nonmissing n | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer information seeking in the past week (proportion) | 6,369 | 0.05 (0.22) |

| AP stories per day in the past week (# stories per day) | 6,369 | 1.40 (0.59) |

| Interviewed within a week of John Kerry’s prostate cancer surgery (proportion) | 6,369 | 0.02 (0.15) |

| Age (in years) | 6,369 | 45.2 (17.4) |

| Female (proportion) | 6,369 | 0.52 (0.50) |

| White (proportion) | 6,068 | 0.72 (0.45) |

| Black (proportion) | 6,068 | 0.11 (0.31) |

| Hispanic (proportion) | 6,068 | 0.12 (0.32) |

| Other (proportion) | 6,068 | 0.06 (0.24) |

| Education (in years) | 6,139 | 12.93 (2.58) |

| Has Internet (proportion) | 6,358 | 0.63 (0.48) |

| Personally had cancer (proportion) | 6,352 | 0.11 (0.31) |

| Family history of cancer (proportion) | 6,319 | 0.62 (0.49) |

| Attention to health news (scale, range 0–12) | 6,327 | 6.21 (3.14) |

Note. The table presents weighted mean and standard deviation estimates for all variables included in subsequent multivariate analyses.

Independent Variable: Cancer News Coverage in the Past Week

To match the timing of the dependent variable, we calculated the average number of AP stories per day that appeared in the week preceding a respondent’s date of interview. The mean value was 1.40 (SD = 0.59; range 0.29 to 3.43), with substantial variability over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Variation in cancer news coverage between October 28, 2002, and April 13, 2003.

We reviewed each AP story to assess whether major celebrity cancer events occurred during the observation period. We defined major celebrity cancer event coverage using three criteria: (1) the story mentioned an individual’s name in the headline, (2) the individual was deemed sufficiently famous that the headline did not include additional descriptors to identify why that person is noteworthy (e.g., “Pop singer Anastacia,” or “UConn coach Calhoun”), and (3) the story was catalogued by the AP as a “Domestic News” story (rather than domain-specific, such as “Sports” or “Entertainment News”). Only one event met these criteria: John Kerry’s prostate cancer surgery, referenced in three “Domestic News” headlines on February 12, 2003.

To separate the effects of this major celebrity cancer event from other cancer news coverage, we created a single indicator variable for individuals who were interviewed between February 12 and February 19 (within a week of Kerry’s surgery) and included this variable as a control for major celebrity events in all multivariate analyses.

Variables Related to Moderating Hypotheses

Slightly less than one in nine respondents (10.8%) reported a personal history of cancer (see Table 1). A much larger proportion of the sample (61.9%) indicated that a close, immediate family member had a history of cancer. Attention to health topics in the media was measured on a 4-point scale. Specifically, respondents were asked, “How much attention do you pay to information about health or medical topics on …” television, radio, newspapers, magazines, and the Internet. Respondents reporting greater levels of attention were assigned higher numerical values (a lot = 3, some = 2, a little = 1, not at all = 0). Attention to the Internet had considerably weaker correlations with other sources than did other media and substantially reduced scale reliability. We thus created an additive scale ranging in value from 0 to 12 using responses to each medium except the Internet (Cronbach’s α = 0.72). The mean attention scale value was 6.21 (SD = 3.14). Other variable distributions are found in Table 1.

Analytic Approach

We tested H1 by estimating a bivariate logistic regression model to predict the odds of cancer information seeking in the past week by the average number of AP stories appearing in the past week. We tested H2, H3, and H4 using a series of interactions between each moderating variable (centered when continuous) and cancer news coverage (centered) to assess whether each interaction produced odds ratios that were statistically different from one.1 Finally, we tested a comprehensive multivariate logistic regression model including news coverage, each moderating variable, each significant interaction, and a series of demographic controls shown in previous work to influence cancer information seeking (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, Internet access, and exposure to the major celebrity cancer event) to assess whether results were robust to potential confounders (Fox & Ranie, 2002; Freimuth et al., 1989; Johnson, 1997).

Results

H1 received limited empirical support. The odds of information seeking were higher during periods of higher cancer news coverage, but this result was only marginally significant (OR = 1.20; 95% CI 0.99–1.45, p < 0.07).

Two of three moderating variable hypothesis received support. Consistent with H2, the relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking in the past week was substantially stronger among individuals who reported paying closer attention to health news in the media (attention* AP stories OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.16, p < 0.01). Consistent with H3, the relationship between cancer news coverage and cancer information seeking in the past week was substantially stronger among respondents with a family history of cancer (family history* AP stories OR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.07–2.33, p < 0.05). H4 received no support. The interaction between personal cancer history and cancer news coverage was not statistically significant (personal history* AP stories OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.60–1.48, p > 0.10) and was excluded from subsequent models.

Comprehensive logistic regression models confirmed results observed in earlier models. The main association between cancer news coverage and information seeking in the past week disappeared when the interaction terms were included in the model (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.51–1.02, p > 0.05), see Table 2. The major celebrity cancer event (John Kerry’s prostate cancer surgery) was not associated with higher levels of information seeking (OR = 1.12, 95% CI 0.48–2.62, p > 0.05). Higher education, personal cancer experience, family history of cancer, and greater attention to health news increased the odds of information seeking in the past week. Consistent with H2 and H3, interaction terms for health news attention and family history were significant when controlling for potential confounders (attention* AP stories OR = 1.10, 95% CI 1.03–1.18, p < 0.01; family history* AP stories OR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.03–2.37, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Logistic regression predicting cancer information seeking in the past week

| n = 5,993 | Odds ratio [95% CI] |

|---|---|

| Average number of AP stories per day in the past week | 0.72 [0.51–1.02] |

| Interviewed within week of John Kerry cancer surgery | 1.12 [0.48–2.62] |

| Age | 1.00 [0.99–1.02] |

| Female | 1.09 [0.83–1.43] |

| Black (vs. White) | 1.47 [0.99–2.19] |

| Hispanic (vs. White) | 1.23 [0.60–2.51] |

| Other (vs. White) | 1.72 [0.93–3.17] |

| Years of education | 1.10**[1.04–1.17] |

| Has Internet | 1.29 [0.86–1.93] |

| Personally had cancer | 2.99*** [2.15–4.15] |

| Family history of cancer | 1.69** [1.25–2.28] |

| Family history of cancer* Number of AP stories | 1.56* [1.03–2.37] |

| Attention to health news | 1.17*** [1.12–1.24] |

| Attention to health news* Number of AP stories | 1.10** [1.03–1.18] |

Note. Table 2 analyses used replicate weights and jackknife standard error estimates. Cells contain adjusted odds ratio estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

denotes odds ratios significantly different from one at p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

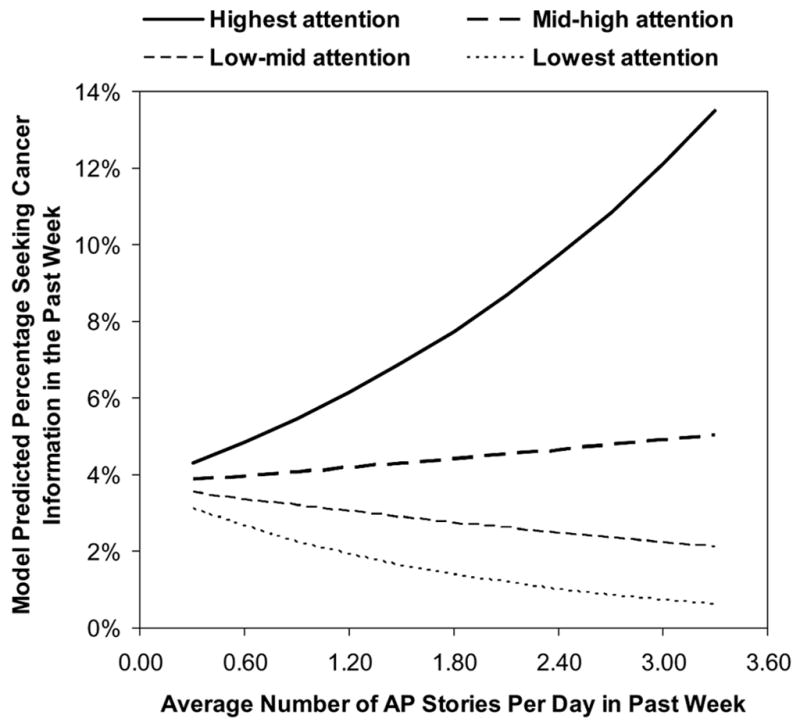

To gain a clearer understanding of the relationships between variables involved in H2 and H3, we used logistic regression model parameter estimates to predict cancer information seeking by each interaction pair. Figure 2 plots model-predicted cancer information seeking (in percentages) by attention to health news (in quartiles) and cancer news coverage in the past week. A positive relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking was apparent only among respondents in the highest quartile of health media attention. The model predicted a dramatic increase in cancer information seeking, with greater cancer news coverage (from 4.3% at the minimum number of AP stories per day to 13.5% at the maximum number of stories per day) among individuals in the highest attention quartile. Conversely, the model predicted generally flat relationships between cancer news coverage and information seeking in the past week at the other three quartiles of attention to health news.

Figure 2.

Model predicted relationship between cancer news coverage and cancer information seeking in the past week by attention to health news in quartiles (n = 5,993).

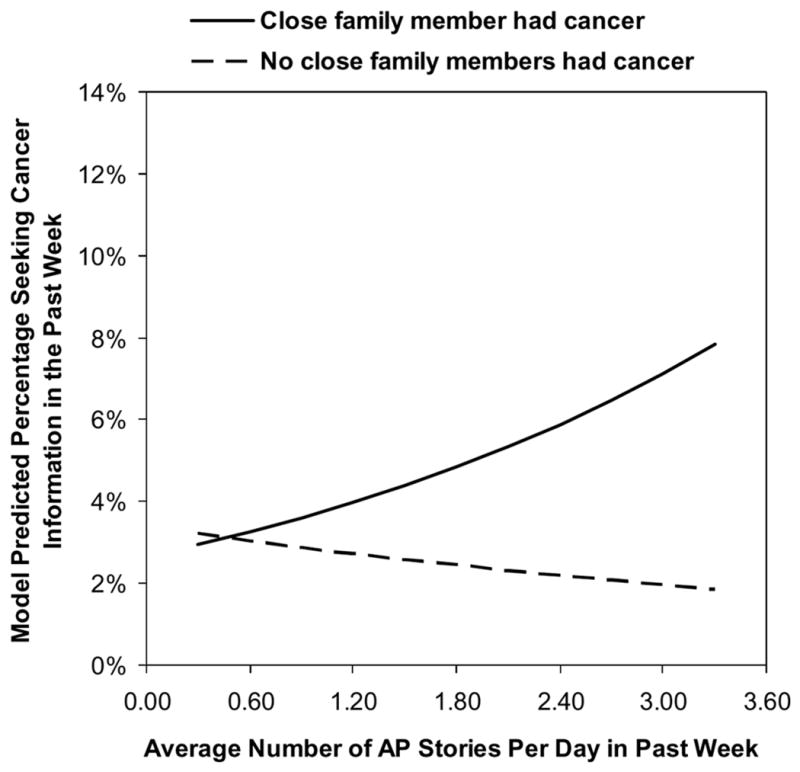

Figure 3 plots model-predicted cancer information seeking (in percentages) by family cancer history and cancer news coverage in the past week. The model predicted cancer information seeking to increase with greater cancer news coverage (from 3.0% at the minimum number of AP stories per day to 7.8% at the maximum number of daily stories) among individuals with a family history of cancer. The model predicted a flat relationship between cancer news coverage and information seeking in the past week among respondents without family cancer history.

Figure 3.

Model predicted relationship between cancer news coverage and cancer information seeking in the past week by family cancer history (n = 5,993).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence that routine cancer news coverage is associated with cancer information seeking among a notable proportion of adults. The study observation period included only one major celebrity cancer event, and the effect of that event on information seeking was negligible and controlled for in multivariate models. We observed a positive, marginally significant relationship between noncelebrity event cancer news coverage and cancer information seeking (limited support for H1). Interaction terms and plots of model-predicted values revealed that cancer news coverage was associated only with information seeking among two subgroups: (1) respondents who paid close attention to health news on television, radio, newspapers, and magazines (supporting H2), and (2) individuals with a family history of cancer (supporting H3). These two groups actively responded to periods of elevated cancer news coverage by seeking information about cancer. Cancer information seeking did not vary by intensity of cancer news coverage for those without family cancer history and for those who did not pay close attention to health news. Respondents who personally had cancer, while more likely to seek cancer information regardless of news coverage, did not respond to periods of elevated cancer news coverage by seeking information (providing no support for H4).

There were dramatic differences between cancer news coverage effects on information seeking among individuals in the highest quartile of health news attention and the rest of the population. These results are consistent with information-seeking models (e.g., Griffin et al., 1999; Johnson, 1997) that highlight the importance of individuals’ habitual patterns of media use on information seeking. Persuasion theory and research also suggest that information exposure, without sufficient message attention and processing, are unlikely to lead to subsequent information engagement (Griffin et al., 1999; McGuire, 2001; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Health news attention measures may capture the type of engagement necessary to produce a meaningful impact on information seeking.

On the other hand, attention measures have been criticized for confounding exposure with personality or contextual influences such as issue involvement, life experience, motivation to process information, and personal values (e.g., Romantan et al., 2005; Slater & Raskinski, 2005). It is also unclear to what extent the attention variable measures a relatively stable characteristic or whether attention to health news varies over time (Chaffee & Schleuder, 1986). Depending on the answer, the implications for purposive attempts to promote cancer information seeking may be quite different. If attention to health news stories is a stable phenomenon, efforts to promote cancer information seeking might focus on ways to reach those individuals who are less interested in health news topics. If attention is not stable, interventions might focus on ways to increase interest in news stories about health. In-depth, qualitative interviews with future survey respondents might help aid our understanding of the extent to which attention measures capture exposure, personality characteristics, motivation, or something else.

There were meaningful differences in cancer news coverage effects on information seeking by family cancer history, but a personal cancer diagnosis did not moderate the relationship. While we can only speculate, it is possible that some proportion of respondents with personal cancer history experience anxiety and “information overload,” which in turn makes them less likely to engage with cancer information (avoidance) in response to news coverage. Conversely, others may respond to the anxiety associated with cancer experience by becoming more likely to seek information in response to cancer news coverage (e.g., Brashers et al., 2002; Johnson, 1997). The net effect in such a scenario would result in no detectable effect of cancer news coverage on information seeking among the overall pool of respondents who have had cancer. Cancer news coverage may be equally salient to respondents with a family history of cancer (e.g., via increased risk or desire to find information for others), but such individuals may not experience the same level of anxiety in response to cancer news. As a result, they may be more likely to respond to periods of elevated cancer news coverage by seeking information.

Study Implications

We drew a distinction between routine news coverage and coverage of major celebrity news events. While Nancy Reagan’s breast cancer diagnosis may have had substantial implications for cancer information seeking on the population level (Freimuth et al., 1989; Stoddard et al., 1990), events like these are impossible to plan or predict. Purposeful efforts by public health organizations, however, exert considerable influence on what topics are covered in the news. Public health advocates, researchers, and journal editors thus have the potential to influence cancer news coverage and health behaviors among segments of the population (e.g., Schooler, Sundar, & Flora, 1996; Stillman, Cronin, Evans, & Ulasevich, 2001).

News media reports are one of the primary ways the public learns about new findings and changes in medical science (Johnson, 1997; Yeaton et al., 1990), but news reports often distill study findings into simple messages, obscuring complexities (e.g., Stryker, 2002). Our results have dual implications in this context. On the one hand, they make it clear that even routine news coverage of cancer has effects on information seeking for some part of the population. On the other hand, our findings indicate that many people do not seek additional information after hearing news reports about new studies. If news reports are inevitably limited in scope, and for much of the population do not drive further information seeking, these results reinforce the view that health care providers play an essential role in making up for this gap. Physicians are unlikely, however, to have more time available in the future than now to educate patients about their choices and engage them in the decision-making process. Thus, our findings raise important questions as health care decisions become more complex and patients increasingly are expected to play a more active role in making decisions. Innovative interventions to help a greater part of the population become more informed consumers of health care are warranted.

Our findings also raise concerns about the potential for widened gaps in cancer knowledge between large segments of the population in the future. The knowledge gap hypothesis suggests that individuals of higher social status acquire information more quickly than lower status individuals, so that the gap in knowledge between these groups increases over time (Tichenor, Donohue, & Olien, 1970). Our results suggest that the cancer knowledge gap between those who pay attention to health news and those who do not is likely to increase over time. Post-hoc ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses showed that education was strongly associated with health news attention (β = 0.19, p < 0.001). Furthermore, published analyses of HINTS data show that the cancer information-seeking measure used in this study is also associated with higher levels of cancer knowledge (Shim et al., 2006). Combined, these findings suggest that differential levels of information seeking in response to cancer news by health news attention may explain a portion of knowledge gaps between high and low educated individuals. Many adults, particularly those with fewer years of education, may require continued active efforts by public health advocates and medical practitioners to disseminate information relevant to cancer prevention, screening, and treatment.

Study Limitations

The study’s independent variable, the average number of AP stories per day in the past week, is an indirect measure of media influence. It is impossible to know whether respondents actually read, saw, or heard the cancer news stories. The indirect approach, however, also has notable advantages. First, indirect exposure measures are not subject to selectivity biases inherent to self-report recall measures (Slater, 2004). The fact that AP coverage measures are independent of survey responses eliminates the possibility that many alternate third-variables (e.g., selectivity, better memory, greater interest in news) account for associations between exposure and information seeking. Furthermore, the reverse causal pathway is highly unlikely in this scenario, since it is implausible that information seeking would cause the AP to issue more news stories about cancer. As a result, the observed association between cancer news coverage and cancer information seeking likely represents a cause–effect relationship, a conclusion that could not be drawn using self-reported news exposure. Second, individuals do not have to read or watch a news story about cancer to hear about it. Cancer news might stimulate conversation between those who saw the news item and those who did not (e.g., Katz & Lazarsfeld, 1955). As a result, the use of self-reported exposure measures may miss important indirect effects that other measures (such as AP coverage) may detect. Finally, recent studies evaluating the effectiveness of media messages using direct (Farrelly et al., 2002) and indirect exposure measures (Farrelly, Davis, Haviland, Messeri, & Healton, 2005) have reached similar conclusions about campaign effectiveness, providing additional evidence that indirect measures are valid indicators of exposure.

The use of automated search terms to assess AP cancer news coverage volume using the Lexis-Nexis database has notable strengths and weaknesses. On one hand, automated search terms may reduce the risk of human error in classifying stories by topic. A computer program will code an article the same way every time if given the same codebook, but the same might not be said about human coders. On the other hand, automated search terms limit content coding specificity. We did not attempt to code for more detailed article features, including story framing, topic specificity (e.g., prevention vs. treatment), story length, placement within the paper (e.g., front page vs. health section), or other potentially meaningful characteristics with the exception of major celebrity cancer news events. Many of these features are subjective in nature and not easily captured by a search term (e.g., story framing), while others are not categorized by Lexis-Nexis (e.g., appearance in the front page vs. another section). Constraints on specificity highlight the practical limitations of using automated search terms in studying news media content or effects. In this application, the method makes the de facto assumption that each story is equally influential in promoting cancer information seeking. Violation of this assumption would lead to measurement error, which in turn would bias findings toward null results. The fact that we were able to detect an interaction between AP news coverage volume and attention to health news on information seeking might be viewed as particularly compelling in this context.

HINTS data are also subject to limitations. The relatively low response rate (34.5%) raises questions about how well the sample represents the national population. While the use of weights alleviates some concerns about the sample’s distribution on major demographic categories (age, gender, and race/ethnicity), it cannot correct for differences between respondents and those who did not participate. In addition, only a small proportion of the sample engaged in information seeking in the past week. Data collection occurred across only 6 months, reducing the amount of variability in news coverage compared with what might have been observed over a longer time period. Both of these considerations reduce the likelihood of detecting a cancer news coverage effect. The fact that we detected an effect among respondents with high attention to health news and among those with a family cancer history, both hypothesized to increase the relationship between news coverage and information seeking, might be viewed as compelling evidence in this context.

Our outcome measure did not specify where seekers looked for information. Different sources (e.g., physicians vs. Internet) may have differential impact on decisions about cancer prevention, screening, or treatment behaviors (Niederdeppe et al., 2007). HINTS did ask information seekers the follow-up question: “The most recent time you looked for information on cancer, where did you look first?” Among respondents seeking cancer information in the past week, 42.9% mentioned the Internet as their first source, followed by books (15.0%) and magazines (12.6%). The number of individuals who sought cancer information from specific sources was far too limited to assess differences in cancer news coverage effects on seeking by source. Future studies might address this limitation by assessing the relationship between the cancer news coverage and source-specific information-seeking data (e.g., volume of web searches about cancer, calls to cancer information hotlines).

Furthermore, reliance on self-reported information seeking as the study’s outcome does not establish the nature of the health outcomes resulting from that seeking behavior. Although cross-sectional data does not permit a causal claim, individuals who report cancer information seeking in the HINTS data are also more knowledgeable about cancer and are more likely to have engaged in cancer screening behaviors (Shim et al., 2006). This measure is too limited, however, to do more than hint at the implications of cancer news coverage for population health.

Conclusions

Results suggest that a notable segment of the population actively responds to periods of elevated cancer news coverage by seeking additional information. At the same time, our findings raise concerns about the potential for widened gaps in cancer knowledge and behavior between large segments of the population in the future. This study underscores the importance of interactions in media effects research and joins a growing literature devoted to understanding the conditions under which individuals seek health information.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the NCI Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication (CECCR) at the University of Pennsylvania (P50 CA101404) and the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program for funding this study. The authors also thank Joseph Cappella and Vincent Price for their insightful comments and others associated with Penn’s CECCR for suggestions on improving the article.

APPENDIX A: Cancer Synonyms

cancer, cancers, cancerous, actinic keratoses, anticancer, astrocytoma, carcinogen, Hodgkin’s, leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, meningioma, mesothelioma, mycosis, myeloma, neuroblastoma, onoclog!, osteosarcoma, pheochromocytoma, precancerous lesion, retinoblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and sarcoma.

APPENDIX B

Lexis-Nexis Search Term for Cancer-Focused News Coverage ((headline(cancer! OR leukemia! OR lymphoma! OR melanoma! OR carcino! OR anticancer! OR mesothelioma!) AND NOT headline(dead OR dies OR died OR lawsuit OR jury OR settlement OR feline)) OR (atleast4(BODY(cancer!)) OR atleast4(BODY(leukemia!)) OR atleast4(BODY(lymphoma!)) OR atleast4(BODY (melanoma!)) OR atleast4(BODY(carcino!)) OR atleast4(BODY(anticancer)) OR atleast4(BODY(mesothelioma!)) OR atleast4(BODY(hodgkin!)) AND NOT headline(dead OR dies OR died OR lawsuit OR jury OR settlement OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam)) OR (atleast3(BODY(cancer!)) AND (BODY (leukemia! OR lymphoma! OR melanoma! OR carcino! OR anticancer OR tumor OR mesothelioma! OR hodgkin!)) AND NOT headline(dead OR dies OR died OR lawsuit OR jury OR settlement OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam OR support groups)) OR (atleast2(BODY(cancer!)) AND (atleast2(BODY (leukemia!)) OR atleast2(BODY(lymphoma!)) OR atleast2(BODY(melanoma!)) OR atleast2(BODY(carcino!)) OR atleast2(BODY(anticancer)) OR atleast2(BODY-(mesothelioma!)) OR atleast2(BODY(hodgkin!)) AND NOT headline(dead OR dies OR died OR lawsuit OR jury OR settlement OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam))) AND NOT (section (obit! OR death notice! OR in memoriam OR deaths)) AND NOT (series (obit! OR death notice! OR in memoriam OR deaths)) AND NOT body ((feline pre/1 leukemia) or (capricorn) or (upcoming events)) AND NOT(state & local wire) AND NOT(worldstream) AND NOT(associated press online) AND NOT(international news) AND NOT(AP news in brief) AND NOT(developments in the news industry).

Footnotes

−2 log likelihood chi-square tests for nested models, a more formal test of whether the interactions improved model fit, are not available for jackknife standard error estimates of logistic regressions.

Contributor Information

JEFF NIEDERDEPPE, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

DOMINICK L. FROSCH, Department of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

ROBERT C. HORNIK, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

References

- American Urological Association (AUA) Prostate-specific antigen best practice policy. Oncology. 2000;14:267–286. Retrieved May 5, 2005, from http://www.cancernetwork.com/journals/oncology/o0002e.htm. [PubMed]

- Brashers DE, Goldsmith DJ, Hsieh E. Information seeking and avoiding in health contexts. Human Communication Research. 2002;28:258–272. [Google Scholar]

- Bubela TM, Caulfield TA. Do the print media “hype” genetic research? A comparison of newspaper stories and peer-reviewed research papers. Canadian Meidcal Association Journal. 2004;170:1399–1407. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion EW. Medical research and the news media. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:2436–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey MK, Allen M, Emmers-Sommer T, Sahlstein E, Degooyer D, Winters AM, Wagner AE, Dun T. When a celebrity contracts a disease: The example of Earvin “Magic” Johnson’s announcement that he was HIV positive. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:249–265. doi: 10.1080/10810730305682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffee SH, Schleuder J. Measurement and effects of attention to media news. Human Communication Research. 1986;13:76–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken S. The heuristic model of persuasion. In: Zanna MP, Olson JM, Herman CP, editors. Social influence: The Ontario symposium. Vol. 5. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Condit C. Science reporting to the public: Does the message get twisted? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2004;170:1415–1416. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Fendrick M, Inadomi J, Cowen ME, Carpenter D, Vijan S. The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: The Katie Couric effect. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:1601–1605. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman M. Developing a profile of consumer intention to seek out additional information beyond a doctor: The role of communicative and motivation variables. Health Communication. 2005;17:1–16. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1701_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle V. Reporting research in medical journals and newspapers. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:920–923. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6984.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan DP. Predictions of public opinion from the mass media. New York: Greenwood Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fan DP. Impact of persuasive information on secular trends in health-related behaviors. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fan DP, Holway WB. Media coverage of cocaine and its impact on usage patterns. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 1994;6:139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fan DP, Tims AR. The impact of the news media on public opinion: American presidential election 1987–1988. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 1989;1:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, Messeri P, Healton CG. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between “truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:425–431. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Healton CG, Davis KC, Messeri P, Hersey JC, Haviland ML. Getting to the truth: Evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:901–907. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Ranie L. Vital decisions: How Internet users decide what information to trust when they or their loved ones are at risk. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Greenberg RH, DeWitt J, Romano RM. Covering cancer: Newspapers and the public interest. Journal of Communication. 1984;34(1):62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Stein JA, Kean TJ. Searching for health information: The cancer information service model. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: Past research and future directions. American Journal of Preventive Medcicine. 1999;17:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin RJ, Dunwoody S, Neuwirth K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research. 1999;80:S230–S245. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD. Cancer-related information seeking. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM, Frosch DL. Decision making in medicine and health care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:525–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Lazarsfeld P. Personal influence. New York: The Free Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Knaus CS, Pinkleton BE, Austin EW. The ability of the AIDS quilt to motivate information seeking, personal discussion, and preventive behavior as a health communication intervention. Health Communication. 2000;12:301–316. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1203_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ. Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. In: Rice RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public communication campaigns. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 22–48. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RG, Thompson IM, Austenfeld MS, Cooner WH, Correa RJ, Gibbons RP, Miller HC, Oesterling JE, Resnick MI, Smalley SR, et al. Prostate cancer clinical guidelines: Panel summary report on the management of clinically localized prostate cancer. Journal of Urology. 1995;154:2144–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer S, Greener S, Beauvais J, Salovey P. Accuracy of health research reported in the popular press: Breast cancer and mammography. Health Communication. 1994;7:147–161. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Prostate cancer (PDQ1): Screening (summary of evidence) 2003 Retrieved May 5, 2005, from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/prostate/HealthProfessional.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast cancer treatment guidelines for patients: Version VI. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2004. Sep, Retrieved July 25, 2005, from http://www.nccn.org/patients/patient_gls/_english/breast/contents.asp. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Traffic safety facts: 2003 Data. Washington, DC: National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2004. On-line. Available: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/pdf/nrd-30/NCSA/TSF2003/809761.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Hesse BW, Croyle RT, Willis G, Arora NJ, Rimer BK, Viswanath KV, Weinstein N, Alden S. The health information national trends survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:443–460. doi: 10.1080/10810730490504233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Hornik R, Kelly B, Frosch D, Romantan A, Stevens R, Barg F, Weiner J, Schwarz S. Examining the dimensions of cancer-related information scanning and seeking behavior. Health Communication. 2007;22:153–167. doi: 10.1080/10410230701454189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Attitudes and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Kanter EJ, Bednarczyk B, Tastad PL. Importance of the lay press in the transmission of medical knowledge to the scientific community. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:1180–1183. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. News media coverage of smoking and health is associated with changes in population rates of smoking cessation but not initiation. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:145–153. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky PF, Hurwitz ES, Schonberger LB, Gunn WJ. Reye’s syndrome and aspirin. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1988;260:657–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Assaf AR, Lefebvre RC, Lasater TM, Niknian M, Carleton RA. Information-seeking about health in a community sample of adults: Correlates and associations with other health-related practices. Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17:379–393. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romantan A. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Philadelphia, PA: Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania; 2004. The social amplification of commercial aviation risks in the US news media: A longitudinal analysis of media effects on air travel behavior, 1978–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Romantan A, Hornik R, Weiner J, Price V, Cappella J, Viswanath K. Learning about cancer: A comparative analysis of the performance of eight measures of incidental exposure to cancer information in the mass media. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association; New York, NY. May 26–30, 2005.2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M. Attitudes of scientists and journalists toward media coverage of science news. Journalism Quarterly. 1979;56:18–26. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Salton G, McGill MJ. Introduction to modern information retrieval. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schooler C, Sundar SS, Flora J. Effects of the Stanford five-city project media advocacy program. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23:346–364. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf BF, Street RL. The patient as central construct: Shifting the emphasis. Health Communication. 1997;9:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shim M, Kelly B, Hornik R. Cancer-related seeking and scanning behavior is associated with cancer knowledge, lifestyle and screening behaviors. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 2):157–172. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Operationalizing and analyzing exposure: The foundation of media effects research. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2004;81:168–183. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rasinski KA. Media exposure and attention as mediating variables influencing social risk judgments. Journal of Communication. 2005;55:810–827. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2005. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55:31–44. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Kahn JS. The effects of professional and media warnings about the association between asprin use in children and Reye’s syndrome. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 265–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman FA, Cronin KA, Evans WD, Ulasevich A. Can media advocacy influence newspaper coverage of tobacco: Measuring the effectiveness of the American stop smoking intervention study’s (ASSIST) media advocacy strategies. Tobacco Control. 2001;10:137–144. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard AM, Zapka JG, Schoenfeld S, Costanza ME. Effects of a news event on breast cancer screening survey responses. In: Engstrom PF, Rimer B, Mortenson LE, editors. Advances in cancer control: Screening and prevention research. New York: Wiley; 1990. pp. 259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker JE. Reporting medical information: Effects of press releases and newsworthiness on medical journal articles’ visibility in the news media. Preventive Medicine. 2002;35:519–530. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker JE. Media and marijuana: A longitudinal analysis of news media effects on adolescents’ marijuana use and related outcomes, 1977–1999. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:305–328. doi: 10.1080/10810730305724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker JE, Wray R, Hornik RC, Yanovitzky I. Validation of database search terms for content analysis: The case of cancer news coverage. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2006;83:413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Taubes G. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science. 1995;269:164–169. doi: 10.1126/science.7618077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichenor PJ, Donohue GA, Olien CN. Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1970;34:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Workshop summary: Scientific evidence on condom effectiveness for sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention. Washington, DC: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, USDHHS; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Screening for breast cancer: Recommendations and rationale. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2002a. Retrieved July 12, 2005, from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Screening for colorectal cancer: Recommendations and rationale July 2002. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2002b. Retrieved May 5, 2005, from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/colorectal/colorr.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Originally in Annals of Internal Medicine. Vol. 137. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2002c. Screening for prostate cancer: Recommendations and rationale; pp. 915–916. 2002. Retrieved May 5, 2005, from http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/prostatescr/prostaterr.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Surgeon General (USSG) The health benefits of smoking cessation: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. On-line. Available.: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/C/T/ [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Surgeon General (USSG) The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. On-line. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/sgr_2004/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Watt AH, Mazza M, Snyder L. Agenda-setting effects of television news coverage and the effects decay curve. Communication Research. 1993;20:408–435. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I, Bennett C. Media attention, institutional response, and health behavior change—the case of drunk driving, 1978–1996. Communication Research. 1999;26:429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I, Blitz CL. Effect of media coverage and physician advice on utilization of breast cancer screening by women 40 years and older. Journal of Health Communication. 2000;5:117–134. doi: 10.1080/108107300406857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I, Stryker J. Mass media, social norms, and health promotion efforts: A longitudinal study of media effects on youth binge drinking. Communication Research. 2001;28:208–239. [Google Scholar]

- Yeaton W, Smith D, Rogers K. Evaluating understanding of popular press reports on health research. Health Education Quarterly. 1990;7:223–234. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]