Abstract

Sexual behavior in male rats is rewarding and reinforcing. However, little is known about the specific cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating sexual reward or the reinforcing effects of reward on subsequent expression of sexual behavior. The current study tests the hypothesis that ΔFosB, the stably expressed truncated form of FosB, plays a critical role in the reinforcement of sexual behavior and experience-induced facilitation of sexual motivation and performance. Sexual experience was shown to cause ΔFosB accumulation in several limbic brain regions including the nucleus accumbens (NAc), medial prefrontal cortex, ventral tegmental area and caudate putamen, but not the medial preoptic nucleus. Next, the induction of c-Fos, a downstream (repressed) target of ΔFosB, was measured in sexually experienced and naïve animals. The number of mating-induced c-Fos-IR cells was significantly decreased in sexually experienced animals compared to sexually naïve controls. Finally, ΔFosB levels and its activity in the NAc were manipulated using viral-mediated gene transfer to study its potential role in mediating sexual experience and experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. Animals with ΔFosB over-expression displayed enhanced facilitation of sexual performance with sexual experience relative to controls. In contrast, the expression of ΔJunD, a dominant-negative binding partner of ΔFosB, attenuated sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance, and stunted long-term maintenance of facilitation compared to GFP and ΔFosB over-expressing groups. Together, these findings support a critical role for ΔFosB expression in the NAc for the reinforcing effects of sexual behavior and sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance.

Keywords: sexual behavior, sensitization, recombinant adeno-associated viral vector, anterior cingulate area, neuroplasticity, learning

INTRODUCTION

Sexual behavior is highly rewarding and reinforcing for male rodents (Coolen et al. 2004; Pfaus et al. 2001). Moreover, sexual experience alters subsequent sexual behavior and reward (Tenk et al. 2009). With repeated mating experience, sex behavior is facilitated or “reinforced”, evidenced by decreased latencies to initiate mating and facilitation of sexual performance (Balfour et al. 2004; Pfaus et al. 2001). However, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of sexual reward and reinforcement are poorly understood. Sexual behavior and conditioned cues that predict mating have been shown to transiently induce expression of immediate-early gene c-fos in the mesolimbic system of male rats (Balfour et al. 2004; Pfaus et al. 2001). Moreover, it was recently demonstrated that sexual experience induces long-lasting neuroplasticity in the male rat mesolimbic system (Frohmader et al. 2009; Pitchers et al. 2010). In addition, in male rats, sexual experience has been shown to induce ΔFosB, a Fos family member, in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Wallace et al. 2008). ΔFosB, a truncated splice variant of FosB, is a unique member of the Fos family due to its greater stability (Carle et al. 2007; Ulery-Reynolds et al. 2008; Ulery et al. 2006) and plays a role in enhanced motivation and reward for drugs of abuse and the long-term neural plasticity mediating addiction (Nestler et al. 2001). ΔFosB forms a heteromeric transcription factor complex (activator protein-1 (AP-1)) with Jun proteins, preferably JunD (Chen et al. 1995; Hiroi et al. 1998). Through inducible over-expression of ΔFosB, primarily restricted to the striatum using bi-transgenic mice, a drug addicted-like behavioral phenotype is produced despite an absence of previous drug exposure (McClung et al. 2004). This behavioral phenotype includes a sensitized locomotor response to cocaine (Kelz et al. 1999), increased preference for cocaine (Kelz et al. 1999) and morphine (Zachariou et al. 2006), and increased cocaine self-administration (Colby et al. 2003).

Similar to drug reward, ΔFosB is upregulated by natural rewarding behaviors and mediates the expression of these behaviors. Over-expression of ΔFosB in the NAc using rodent models increases voluntary wheel running (Werme et al. 2002), instrumental responding for food (Olausson et al. 2006), sucrose intake (Wallace et al. 2008), and facilitates male (Wallace et al. 2008) and female (Bradley et al. 2005) sexual behavior. Thus, ΔFosB may be involved in mediating the effects of natural rewarding experiences. The current study expands on previous studies by specifically investigating the role of ΔFosB in the NAc in the long-term outcomes of sexual experience on subsequent mating behavior and neural activation in the mesolimbic system. First, it was established which brain regions implicated in the reward circuitry and sexual behavior express sex experience-induced ΔFosB. Next, the effect of sex experience-induced ΔFosB on mating-induced expression of c-Fos, a downstream target repressed by ΔFosB (Renthal et al. 2008), was investigated. Finally, the effect of manipulating ΔFosB activity in the NAc (gene over-expression and expression of a dominant negative-binding partner) on sexual behavior and experience-induced facilitation of sexual motivation and performance was determined using viral vector delivery technology.

METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (200–225 grams) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Senneville, QC, Canada). Animals were housed in Plexiglas cages with a tunnel tube in same sex pairs throughout experiments. The colony room was temperature-regulated and maintained on a 12/12 hr light dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum except during behavioral testing. Stimulus females (210–220 grams) for mating sessions received a subcutaneous implant containing 5% estradiol benzoate and 95% cholesterol following bilateral ovariectomy under deep anaesthesia (0.35g ketamine/0.052g Xylazine). Sexual receptivity was induced by administration of 500µg progesterone in 0.1 mL sesame oil approximately 4 hours before testing. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Western Ontario and conformed to CCAC guidelines involving vertebrate animals in research.

Sexual Behavior

Mating sessions occurred during the early dark phase (between 2–6 hours after onset of the dark period) under dim red illumination. Prior to experiment onset, animals were randomly divided into groups. During mating sessions male rats were allowed to copulate to ejaculation or 1 hour, and parameters for sexual behavior were recorded including: mount latency (ML; time from introduction of the female until the first mount), intromission latency (IL; time from introduction of the female until the first mount with vaginal penetration), ejaculation latency (EL; time from the first intromission to ejaculation), post ejaculation interval (PEI; time from ejaculation to first subsequent intromission), number of mounts (M; pelvic thrusting without vaginal penetration), number of intromissions (IM; mount including vaginal penetration) and copulation efficiency (CE = IM/(M+IM)) (Agmo 1997). Numbers of mounts and intromissions were not included in the analysis for animals that did not display ejaculation. Mount and intromission latencies are parameters indicative of sexual motivation, while ejaculation latency, number of mounts and copulation efficiency reflect sexual performance (Hull 2002).

Experiment 1: Expression of ΔFosB

Sexually naïve male rats were allowed to mate in clean test cages (60 × 45 × 50 cm) for 5 consecutive, daily mating sessions or remained sexually naïve. Supplementary Table 1 outlines the behavioral paradigm for experimental groups: naïve no sex (NNS; n=5), naïve sex (NS; n=5), experienced no sex (ENS; n=5) and experienced sex (ES; n=4). NS and ES animals were sacrificed 1 hour following ejaculation on the final day of mating to investigate mating-induced c-Fos expression. NNS animals were sacrificed concurrently with ENS animals 24 hours after final mating session to examine sex experience-induced ΔFosB. Sexually experienced groups were matched for sexual behavior before subsequent testing. No significant differences were detected between groups for any behavioral measures within the appropriate mating session and sex experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior was displayed by both experienced groups (Supplementary Table 2). Controls included sexually naïve males handled concurrently with mating animals ensuring exposure to female odors and vocalizations without direct female contact.

For sacrifice, animals were deeply anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (270mg/kg; i.p.) and perfused intracardially with 50 mL of 0.9% saline, followed by 500 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were removed and post-fixed for 1 h at room temperature in the same fixative, then immersed in 20% sucrose and 0.01% sodium azide in 0.1 M PB and stored at 4°C. Coronal sections (35 µm) were cut with a freezing microtome (H400R, Micron, Germany), collected in four parallel series in cryoprotectant solution (30% sucrose and 30% ethylene glycol in 0.1 M PB) and stored at −20°C. Free floating sections were washed extensively with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3–7.4) between incubations. Sections were exposed to 1% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature to destroy endogenous peroxidases, then blocked in PBS+ incubation solution, which is PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (catalog item 005-000-121; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and 0.4% Triton X-100 (catalog item BP151-500; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in a pan-FosB rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5K; sc-48 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The pan-FosB antibody was raised against an internal region shared by FosB and ΔFosB. The ΔFosB-IR cells were specifically ΔFosB-positive because at the post-stimulus time (24 hours) all detectable stimulus-induced FosB is degraded (Perrotti et al. 2004; Perrotti et al. 2008). In addition, in this experiment, animals mating on the final day (NS, ES) were sacrificed 1 h after mating, thus prior to FosB expression. Western blot analysis confirmed the detection of ΔFosB at approximately 37 kD. After primary antibody incubation, sections were incubated for 1 h in biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 in PBS+; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and then 1 h in avidin-biotin-hoseradish peroxidase (ABC elite; 1:1K in PBS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Following this incubation sections were processed in one of the following ways:

1. Single peroxidase labeling

Sections of NNS and ENS animals were used for a brain analysis of sexual experience-induced ΔFosB accumulation. Following ABC incubation, the peroxidase complex was visualized following treatment for 10 minutes to a chromogen solution containing 0.02% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) enhanced with 0.02% nickel sulfate in 0.1 M PB with hydrogen peroxide (0.015%). Sections were washed thoroughly in 0.1 M PB to terminate the reaction and mounted onto coded Superfrost plus glass slides (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) with 0.3% gelatin in ddH20. Following dehydration, all slides were cover-slipped with DPX (dibutyl phthalate xylene).

2. Dual immunofluorescence

Sections from all four experimental groups containing NAc and mPFC were used for analysis of ΔFosB and c-Fos. Following ABC incubation, sections were incubated for 10 min with biotinylated tyramide (BT; 1:250 in PBS + 0.003% H2O2 Tyramid Signal Amplification Kit, NEN Life Sciences, Boston, MA) and for 30 min with Alexa 488-conjugated strepavidin (1:100; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Sections were then incubated overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antibody specifically recognizing c-Fos (1:150; sc-52; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), followed by a 30 min incubation with goat anti-rabbit Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Following staining, the sections were washed thoroughly in 0.1 M PB, mounted onto coded glass slides with 0.3% gelatin in ddH20 and cover-slipped with an aqueous mounting medium (Gelvatol) containing the anti-fading agent 1,4-diazabicyclo(2,2)octane (DABCO; 50 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Immunohistochemical controls included omission of either or both primary antibodies, resulting in absence of labeling in the appropriate wavelength.

Data Analysis

Brain analysis of ΔFosB

Two experimenters blind to treatment performed the brain wide scan on coded slides. ΔFosB-immunoreactive (-IR) cells throughout the brain were semi-quantitatively analyzed using a scale to represent the number of ΔFosB-positive cells as outlined in Table 1. In addition, based on semi-quantitative findings, numbers of ΔFosB-IR cells were counted using standard areas of analysis in brain areas implicated in reward and sexual behavior using a camera lucida drawing tube attached to a Leica DMRD microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany): NAc (core (C) and shell (S); 400×600µm) analyzed at three rostral-caudal levels (Balfour et al. 2004); ventral tegmental area (VTA; 1000×800µm) analyzed at three rostral-caudal levels (Balfour et al. 2004) and VTA tail (Perrotti et al. 2005); prefrontal cortex (anterior cinglulate area (ACA); prelimbic cortex (PL); infralimbic cortex (IL); 600×800µm each); caudate putamen (CP; 800×800µm); and medial preoptic nucleus (MPN; 400×600 µm) (Supplementary Figures 1–3). Two sections were counted per subregion, and averaged per animal for calculation of the group mean. Sexually naïve and experienced group averages of ΔFosB-IR cells were compared for each subregion using unpaired t-tests.

Table 1. Summary of ΔFosB expression in sexually naïve and experienced animals.

Semi-quantitative analysis of ΔFosB expression in sexually naïve and experienced animals (n=5 each group). Numbers of ΔFosB-IR cells were rated using the following scale: − (absent; 0–1 cell), + (low; 2–10 cells), ++ (10–50 cells), +++ (50–100 cells) and ++++ (highest; >100 cells).

| Brain Region | Control | Sexual Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex | ||

| Anterior Cingulate Area | ++ | +++ |

| Prelimbic Area | ++ | +++ |

| Infralimbic Area | ++ | ++++ |

| Nucleus Accumbens | ||

| Core | ++ | ++++ |

| Shell | ++ | ++++ |

| Caudate Putamen | ++ | ++++ |

| Ventral Pallidum | − | − |

| Globus Pallidum | − | − |

| Olfactory Tubercle | + | ++ |

| Piriform Cortex | + | ++ |

| Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis, Principal Nucleus |

− | + |

| Medial Preoptic Area | + | + |

| Hypothalamus | ||

| Anterior | − | +++ |

| Lateral | − | + |

| Posterior | + | ++ |

| Suprachiasmatic Nucleus | + | ++ |

| Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus |

− | − |

| Amygdala | ||

| Basolateral | − | ++ |

| Central | − | + |

| Medial | − | + |

| Hippocampus | ||

| Dentate Gyrus | + | ++ |

| CA1 | − | − |

| CA3 | + | ++ |

| Ventral Tegmental Area | ++ | +++ |

| Substantia Nigra | − | − |

| Subparafascicular Thalamic Nucleus, Parvocellular |

− | + |

| Periaqueductal Grey | − | + |

Analysis of ΔFosB and c-Fos

Images were captured using a cooled CCD camera (Microfire, Optronics) attached to a Leica microscope (DM5000B, Leica Microsystems; Wetzlar, Germany) and Neurolucida software (MicroBrightfield Inc) with fixed camera settings for all subjects (using 10x objectives). Number of cells expressing c-Fos-IR or ΔFosB-IR in standard areas of analysis in NAc core and shell (400×600µm each; Supplementary Figure 1) and ACA of the mPFC (600×800µm; Supplementary Figure 3) were manually counted by an observer blinded to the experimental groups, in 2 sections per animal using Neurolucida software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT) and averaged per animal. Group averages of c-Fos or ΔFosB cells were compared using two-way ANOVA (Factors: sexual experience and sex activity) and Fisher LSD for post hoc comparisons at a significance level of 0.05.

Experiment 2: ΔFosB expression manipulation

Viral Vector-Mediated Gene Transfer

Sexually naive male Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into groups prior to stereotaxic surgery. All animals received bilateral microinjections of recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors encoding GFP (control; n=12), wild-type ΔFosB (n=11) or a dominant-negative binding partner of ΔFosB termed ΔJunD (n=9) into the NAc. ΔJunD decreases ΔFosB mediated transcription by competitively heterodimerizing with ΔFosB before binding the AP-1 region within gene promoters (Winstanley et al. 2007). Virus titer was determined by qPCR and evaluated in vivo prior to study onset. Titer was 1–2 × 1011 infectious particles per mL. rAAV vectors were injected in a volume of 1.5 µL/side over 7 minutes (coordinates: AP +1.5, ML +/−1.2 from Bregma; DV −7.6 from skull surface according to Paxinos and Watson, 1998) using a Hamilton syringe (5µL; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The vectors produce no toxicity greater than control infusions alone (Winstanley et al, 2007; for details of AAV preparation, see Hommel et al., 2003). Behavioral experiments started 3 weeks after vector injections allowing for optimal and stable viral infection (Wallace et al. 2008). Transgene expression in murine species peaks at 10 days and remains elevated for at least 6 months (Winstanley et al. 2007). At the end of the experiment, the animals were transcardially perfused and NAc sections were immuno-processed for GFP (1:20K; rabbit anti-GFP antibody; Molecular Probes) using an ABC-peroxidase-DAB reaction (as described above) to histologically verify injection sites using GFP as a marker (Supplementary Figure 4). ΔFosB and ΔJunD vectors also contain a segment expressing GFP separated by an internal ribosomal entry site, allowing for injection site verification by GFP visualization in all animals. Only animals with injection sites and spread of virus restricted to the NAc were included in statistical analyses. Spread of virus was generally limited to a portion of the NAc and did not spread rostral-caudally throughout the nucleus. Moreover, spread of virus appeared mostly restricted to either shell or core. However, the variation of injection sites and spread within the NAc did not influence effects on behavior. Finally, GFP injections did not affect sexual behavior or experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior compared to non-surgery animals from previous studies (Balfour et al. 2004).

Sexual Behavior

Three weeks following viral vector delivery, animals mated to one ejaculation (or for 1 hour) for 4 consecutive, daily mating sessions to gain sexual experience (experience sessions) and were subsequently tested for long-term expression of experience induced facilitation of sexual behavior 1 and 2 weeks (test sessions 1 and 2) after the final experience session. Sexual behavior parameters were recorded during all mating sessions as described above. Statistical differences for all parameters during each mating session were compared within and between groups using two-way repeated measures ANOVAs (Factors: treatment and mating session) or one-way ANOVAs (ejaculation latency, number of mounts and intromissions; Factor: treatment or mating session) followed by Fisher LSD or Newman-Keuls tests for post hoc comparisons at a significance level of 0.05. Specifically, the facilitative effects of sexual experience on mating parameters were compared between experience session 1 (naïve) and experience sessions 2, 3, or 4 each, as well as between experimental groups within each experience session. Moreover, to analyze effects of treatment (vector) on long-term facilitation of sexual behavior, mating parameters were compared between experience session 4 and test session 1 and 2 within each treatment group, and compared between experimental groups within each test session.

RESULTS

Sexual experience causes ΔFosB accumulation

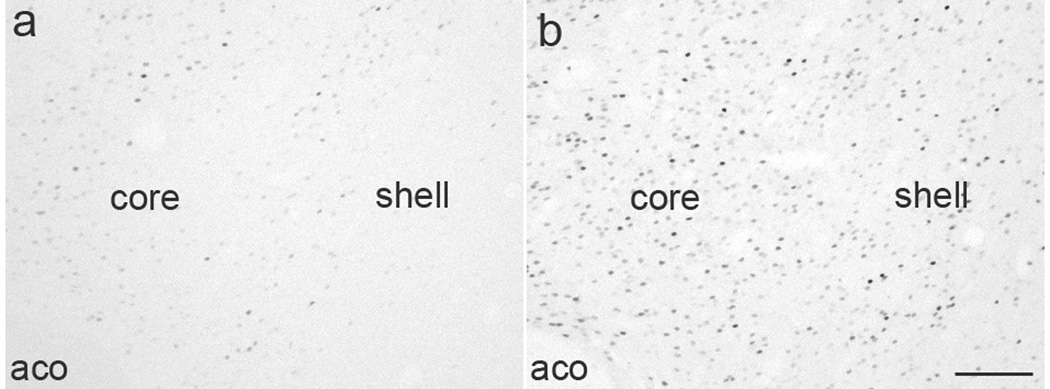

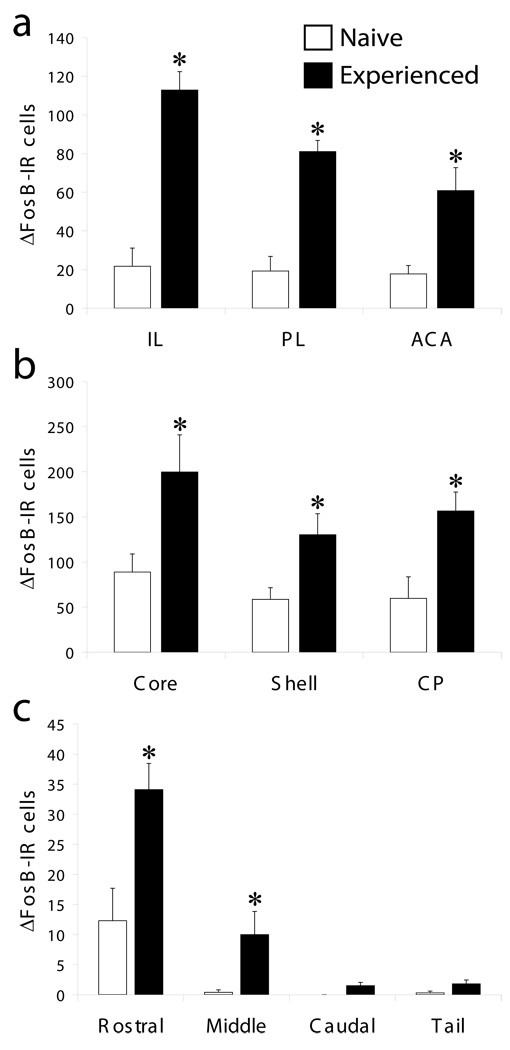

Initially, a semi-quantitative investigation of ΔFosB accumulation throughout the brain in sexually experienced males compared to sexually naïve controls was conducted. A summary of overall findings is provided in Table 1. ΔFosB-IR analysis was furthered by determining the numbers of ΔFosB-IR cells in several limbic-associated brain regions using standard areas of analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates representative images of DAB-Ni staining the NAc of sexually naïve and experienced animals. Significant ΔFosB up-regulation was found in mPFC subregions (Figure 2A), NAc core and shell (2B), caudate putamen (2B) and VTA (2C). In NAc, significant differences existed at all rostral- caudal levels in the NAc core and shell, and data shown in Figure 2 is the average over all rostro-caudal levels. In contrast, there was no significant increase in ΔFosB-IR in the hypothalamic medial preoptic nucleus (NNS: Avg 1.8 +/− 0.26; ENS: Avg 6.0 +/− 1.86).

Figure 1.

Representative images showing ΔFosB-IR cells (black) in the NAc of naïve no sex (A) and experience no sex (B) groups. aco: anterior commissure Scale bar indicates 100 µm.

Figure 2.

Number of ΔFosB-IR cells in: A. infralimbic (IL), prelimbic (PL) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACA) subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex; B. Nucleus accumbens core and shell, and caudate putamen (CP); C. Rostral, middle, caudal and tail sections from the ventral tegmental area. Data are expressed as group means (± SEM). * indicates significant difference from sexually naïve animals (p=0.037-<0.001) (n=5 each group).

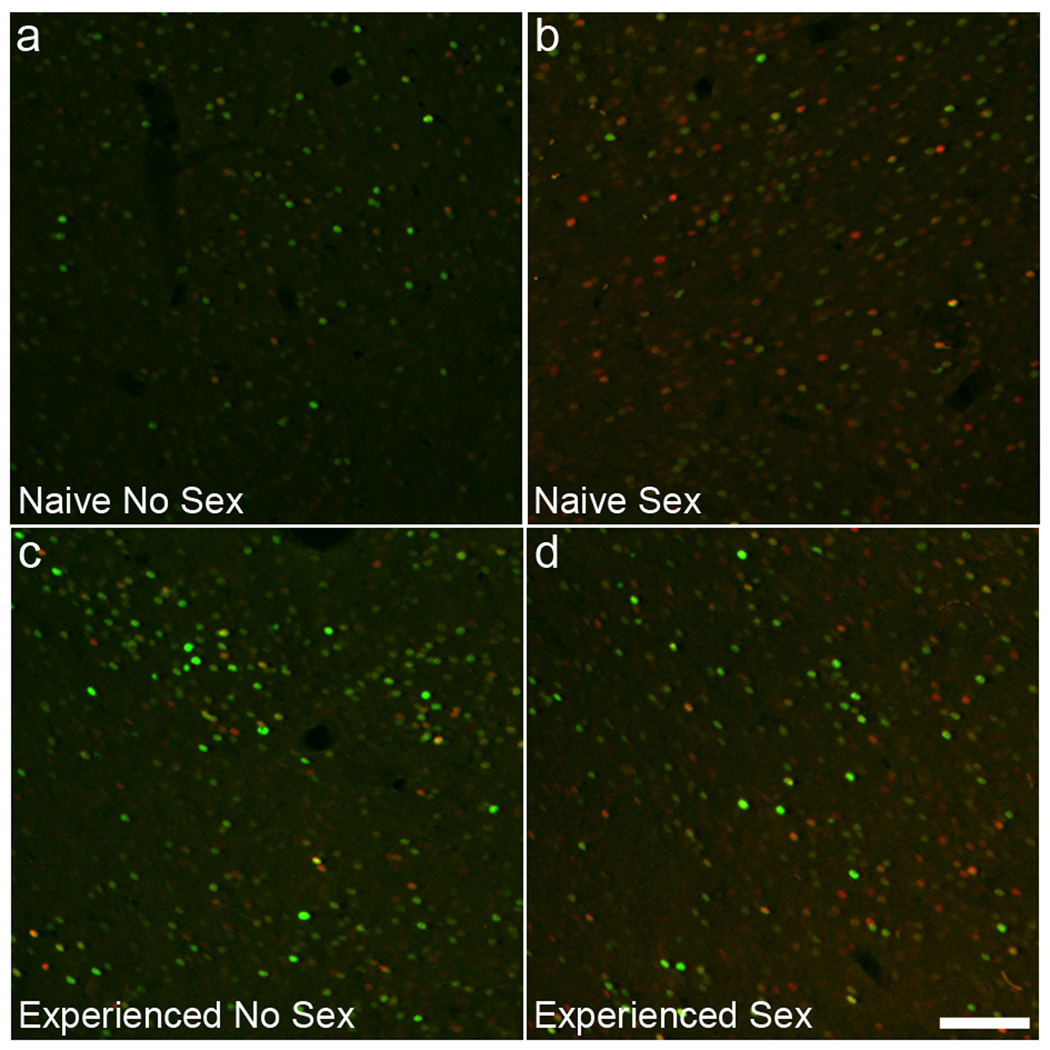

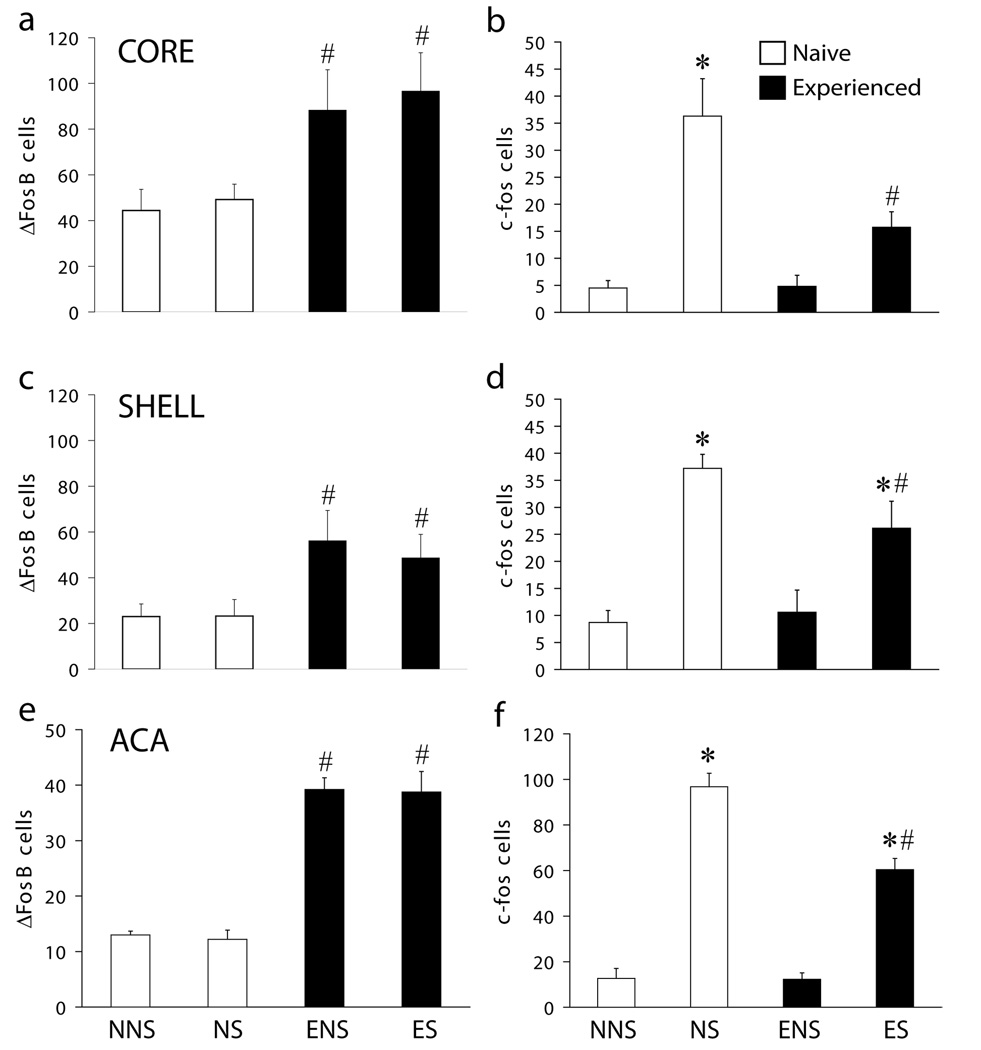

Sexual experience attenuates mating-induced c-Fos

The effect of sexual experience on ΔFosB levels in the NAc were confirmed using fluorescence staining techniques. In addition, effects of sexual experience on expression of c-Fos were analyzed. Figure 3 demonstrates representative images of ΔFosB- (green) and c-Fos (red)-IR cells in all experimental groups (A, NNS; B, NS; C, ENS; D, ES). Sexual experience significantly increased ΔFosB expression in NAc core (Figure 4A: F1,15 = 12.0; p = 0.003) and shell (Figure 4C: F1,15 = 9.3; p = 0.008). By contrast, mating 1 hour prior to perfusion, did not have an effect on ΔFosB expression (Figure 4A,C) and no interaction between sexual experience and mating immediately prior to perfusion was detected. There was an overall effect of mating prior to perfusion on c-Fos expression in both the NAc core (Figure 4B: F1,15 = 27.4; p < 0.001) and shell (Figure 4D: F1,15 = 39.4; p < 0.001). Moreover, an overall effect of sexual experience was detected in the NAc core (Figure 4B: F1,15 = 6.1; p = 0.026) and shell (Figure 4D: F1,15 = 1.7; p = 0.211) and an interaction between sexual experience and mating prior to perfusion was detected in the NAc core (F1,15 = 6.5; p = 0.022), with a trend in the shell (F1,15 = 1.7; p = 0.211; F1,15 = 3.4; p = 0.084). Post hoc analyses demonstrated mating-induced c-Fos expression in core and shell of sexually naïve males (Figure 4B,D). However, in sexually experienced males, c-Fos was not significantly increased in NAc core (Figure 4B) and significantly attenuated in the shell (Figure 4D). Thus, sexual experience caused a reduction of mating-induced c-Fos expression. P-values for specific pair-wise comparisons are in the figure legends.

Figure 3.

Representative images showing ΔFosB (green) and c-Fos (red) in NAc for each experimental group. Scale bar indicates 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Sex experience-induced ΔFosB and mating-induced c-Fos. Numbers of ΔFosB (Core, A; Shell, C; ACA, E) or c-Fos (Core, B; Shell, D; ACA, F) immunoreactive cells for each group: NNS (n=5), NS (n=5), ENS (n=5) or ES (n=4). Data are expressed as group means (± SEM). * indicates significant difference between sexually naïve or experienced sex groups with the appropriate no sex control group (NS vs NNS, ES vs ENS; all p-values p<0.001; except H: ES vs ENS, p=0.008); # indicates significant difference between sexually naïve and experienced sex or no sex groups resp. (ES vs NS; p=0.049-<0.001; ENS vs NNS: p=0.028-<0.001).

The effect of sexual experience on mating-induced c-Fos levels was not restricted to the NAc. A similar attenuation of c-Fos expression was observed in the ACA in sexually experienced animals compared to sexually naïve controls. Sexual experience had a significant effect on ΔFosB expression in the ACA (Figure 4E: F1,15 = 154.2; p < 0.001). Mating prior to perfusion did not have an effect on ΔFosB expression (Figure 4C) but significantly increased c-Fos (Figure 4F: F1,15 = 203.4; p < 0.001) in the ACA. Moreover, mating-induced c-Fos expression in the ACA was significantly decreased by sexual experience (Figure 4F: F1,15 = 15.8; p = 0.001). A two-way interaction between sexual experience and mating prior to perfusion was detected for c-Fos expression (Figure 4F: F1,15 = 15.1; p < 0.001). P-values for specific pair-wise comparisons are in the figure legends. Finally, there was no significant reduction in mating-induced c-Fos expression in the medial preoptic nucleus (NS: Avg 63.5 +/− 4.0; ES: Avg 41.4 +/− 10.09), an area where mating experience did not cause a significant increase in ΔFosB expression, indicating that mating-induced c-Fos expression was not affected in all brain areas.

ΔFosB in the NAc mediates reinforcement of sexual behavior

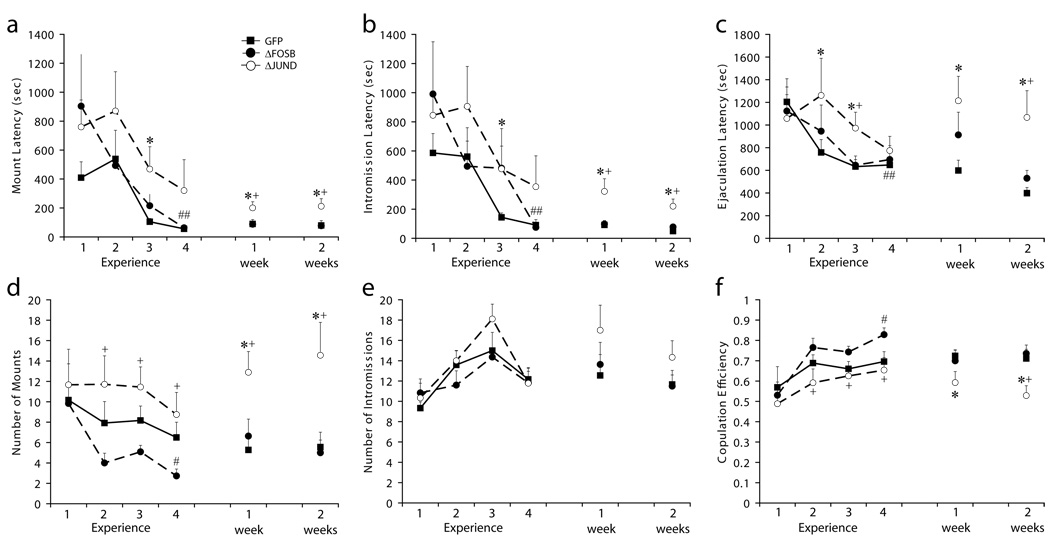

To explore a potential molecular mechanism for reinforcement of sexual behavior as demonstrated by experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior, effects of local manipulation of ΔFosB levels and its transcriptional activity were determined. Sexual experience during the four consecutive experience sessions had a significant effect on mount latency (Figure 5A: F1,23 = 13.8; p = 0.001), intromission latency (Figure 5B: F1,23 = 18.1; p < 0.001), and ejaculation latency (Figure 5C: GFP, F11,45 = 3.8; p = 0.006). GFP control animals displayed the expected experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior and displayed significantly lower latencies to first mount, first intromission and ejaculation during experience session 4 compared to experience session 1 (Figure 5A–C; see figure legend for p-values). This experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior was also observed in the ΔFosB group for mount and intromission latencies, but there was not a significant difference detected in the ejaculation latency (Figure 5A–C). In contrast, ΔJunD animals displayed a stunted facilitation; even though latencies for mounts, intromissions, and ejaculations did decrease with repeated mating sessions, none of these parameters reached statistical significance when compared between experience sessions 1 and 4 (Figure 5A–C). Between group comparisons for each experience session show that ΔJunD had significantly longer latencies to mount, intromit and ejaculate during experience sessions compared to ΔFosB and GFP (Figure 5A–C). In addition, both sexual experience and treatment had significant effects on copulation efficiency (Figure 5F: sexual experience, F1,12 = 22.5; p < 0.001; treatment, F1,12 = 3.3; p = 0.049). ΔFosB males had increased copulation efficiency during experience session 4 compared to experience session 1 (Figure 5F). In addition, ΔFosB animals had significantly fewer mounts preceding ejaculation during experience session day 4, compared to experience session 1 (Figure 5D: F10,43 = 4.1; p = 0.004), and that ΔJunD males had significantly more mounts preceding ejaculation, thus significantly decreased copulation efficiency, than either of the other two groups (Figure 5D and F). Thus, GFP and ΔFosB animals displayed experience-induced facilitation of initiation of sexual behavior and sexual performance, whereas ΔJunD animals did not.

Figure 5.

Sexual behavior of GFP (n=12), ΔFosB (n=11) and ΔJunD (n=9) animals: mount latency (A), intromission latency (B), ejaculation latency (C), number of mounts (D), number of intromissions (E) and copulation efficiency (F). Data are expressed as group means (± SEM). * indicates significant difference from GFP (p=0.047-0.007); + indicates significant difference from ΔFosB (p=0.036-0.005); and # indicates a statistical difference between mating sessions 1 and 4 (GFP: p=0.025-<0.001; ΔFosB: p=0.036-<0.001).

To test the hypothesis that ΔFosB expression is critical for long-term expression of experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior, animals were tested 1 week (test session 1) and 2 weeks (test session 2) after the final experience session. Indeed, facilitated sexual behavior was maintained in both GFP and ΔFosB groups as none of the behavioral parameters differed between test sessions 1 or 2 and the final experience session 4, within GFP and ΔFosB groups (Figure 5A–C; except for ejaculation latency and copulation efficiency in test session 1 for ΔFosB animals). Significant differences between ΔJunD animals and GFP or ΔFosB groups were detected in both test sessions for all sexual behavior parameters (Figure 5A–F). There were no differences detected between or within groups when comparing numbers of intromissions, PEI, or percentages of animals that ejaculated (100% of males in all groups ejaculated during last four mating sessions).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated that sexual experience causes an accumulation of ΔFosB in several limbic-associated brain regions, including the NAc core and shell, mPFC, VTA and caudate putamen. In addition, sexual experience attenuated mating-induced expression of c-Fos in the NAc and ACA. Finally, ΔFosB in the NAc was shown to be critical in mediating facilitation of mating during acquisition of sexual experience and the long-term expression of experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior. Specifically, reducing ΔFosB-mediated transcription attenuated experience-induced facilitation of sexual motivation and performance, while over-expression of ΔFosB in the NAc caused an enhanced facilitation of sexual behavior, in terms of increased sexual performance with less experience. Together, the current findings support the hypothesis that ΔFosB is a critical molecular mediator for the long-term neural and behavioral plasticity induced by sexual experience.

The current findings extend previous studies showing sex experience-induced ΔFosB in the NAc in male rats (Wallace et al. 2008) and female hamsters (Hedges et al. 2009). Wallace et al. (2008) showed that rAAV-ΔFosB over-expression in the NAc enhanced sexual behavior in sexually naïve animals during the first mating session, as evidenced by fewer intromissions to ejaculation and shorter post-ejaculatory intervals, but had no effect in sexually experienced males (Wallace et al. 2008). In contrast, the current study demonstrated no effects of ΔFosB over-expression in sexually naïve males during the first test, but rather during and following the acquisition of sexual experience. ΔFosB over-expressors demonstrated increased sexual performance (increased copulation efficiency) compared to GFP animals. In addition, the current study tested the role of ΔFosB by blocking ΔFosB-mediated transcription using a ΔJunD-expressing viral vector. Prevention of experience-induced increase in ΔFosB expression inhibited experience-induced facilitation of sexual motivation (increased mount and intromission latencies) as well as sexual performance (increased ejaculation latency and number of mounts) and subsequent long-term expression of facilitated sexual behavior. Hence, these data are the first to indicate an obligatory role for ΔFosB in the acquisition of experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior. Moreover, these data show that ΔFosB is also critically involved in the long-term expression of experience-induced facilitated behavior. We propose that this long-term expression of facilitated behavior represents a form of memory for natural reward, hence ΔFosB in NAc is a mediator of reward memory. Sexual experience also increased ΔFosB levels in the VTA and mPFC, areas implicated in reward and memory (Balfour et al. 2004; Phillips et al. 2008). Future studies are required to elucidate a potential significance of ΔFosB up-regulation in these areas for reward memory.

ΔFosB expression is highly stable, thus it has great potential as a molecular mediator of persistent adaptations of the brain following chronic perturbations (Nestler et al. 2001). ΔFosB has been shown to gradually increase in the NAc over multiple cocaine injections and persist for up to several weeks (Hope et al. 1992; Hope et al. 1994). These changes in NAc ΔFosB expression are associated with drug reward sensitization and addiction (Chao & Nestler 2004; McClung & Nestler 2003; McClung et al. 2004; Nestler 2004, 2005, 2008; Nestler et al. 2001; Zachariou et al. 2006). In contrast, the role of ΔFosB in mediating natural reward has been understudied. Recent evidence has surfaced suggesting that ΔFosB induction in the NAc is involved in natural reward. ΔFosB levels are similarly increased in the NAc following sucrose intake and wheel running. The over-expression of ΔFosB in the striatum using bitransgenic mice or viral vectors in rats causes an increase in sucrose intake, enhanced motivation for food and increased spontaneous wheel running (Olausson et al. 2006; Wallace et al. 2008; Werme et al. 2002). The current data substantially add to these reports and further support the notion that ΔFosB is a critical mediator for reward reinforcement and natural reward memory.

ΔFosB may mediate experience-induced reinforcement of sexual behavior via induction of plasticity in the mesolimbic system. Indeed, sexual experience causes a number of long-lasting changes to the mesolimbic system (Bradley & Meisel 2001; Frohmader et al. 2009; Pitchers et al. 2010). At the behavioral level, a sensitized locomotor response to amphetamine and an enhanced amphetamine reward have been shown in sexually experienced male rats (Pitchers et al. 2010); an altered locomotor response to amphetamine has also been observed with female hamsters (Bradley & Meisel 2001). Furthermore, increases in number of dendritic spines and complexity of dendritic arbors have been found following an abstinence period from sexual experience in male rats (Pitchers et al. 2010). The current study suggests ΔFosB may be a specific molecular mediator of the long-term outcomes of sexual experience. In agreement, ΔFosB has recently been shown to be important for inducing dendritic spine changes in response to chronic cocaine administration (Dietz et al. 2009; Maze et al. 2010).

It is not clear which upstream neurotransmitter(s) is responsible for inducing ΔFosB in the NAc, but DA has been proposed as a candidate (Nye et al. 1995). Virtually all drugs of abuse, including cocaine, amphetamine, opiates, cannabinoids, and ethanol, as well as natural rewards, increase ΔFosB in the NAc (Perrotti et al. 2005; Wallace et al. 2008; Werme et al. 2002). Both drugs of abuse and natural rewards increase synaptic DA concentration in the NAc (Damsma et al. 1992; Hernandez & Hoebel 1988a, b; Jenkins & Becker 2003). ΔFosB induction by drugs of abuse has been shown in DA receptor containing cells and cocaine-induced ΔFosB is blocked by a D1 DA receptor antagonist (Nye et al. 1995). Hence, DA release is hypothesized to stimulate ΔFosB expression and thereby mediate reward-related neuroplasticity. Further supporting the idea that ΔFosB levels are DA-dependent is the finding that brain areas where sexual experience altered ΔFosB levels do receive strong dopaminergic input from the VTA, including the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. However, in contrast, ΔFosB is not increased in the medial preoptic area even though this area receives dopaminergic input, albeit from hypothalamic sources (Miller & Lonstein 2009). Future studies are needed to test if mating-induced ΔFosB expression and the effects of sexual experience on sexual motivation and performance are dependent on DA action. The role for DA in sexual reward in male rats is currently not completely clear (Agmo & Berenfeld 1990; Pfaus 2009). There is ample evidence that DA is released in the NAc during exposure to a female or mating (Damsma et al. 1992) and DA neurons are activated during sexual behavior (Balfour et al. 2004). However, systemic injections of DA receptor antagonist do not prevent sexual reward-induced conditioned place preference (Agmo & Berenfeld 1990) and the hypothesis that DA is critical for experience-induced reinforcement of mating is untested.

It is also unclear as to what are the downstream mediators of ΔFosB effects on sexual behavior. ΔFosB has been shown to act as both a transcriptional activator and repressor through an AP-1 dependent mechanism (McClung & Nestler 2003; Peakman et al. 2003). Numerous target genes have been identified, including the immediate early gene c-fos (Hope et al. 1992; Hope et al. 1994; Morgan & Curran 1989; Renthal et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2006), cdk5 (Bibb et al. 2001), dynorphin (Zachariou et al. 2006), sirtuin-1 (Renthal et al. 2009), NFκB subunits (Ang et al. 2001), and the AMPA glutamate receptor GluR2 subunit (Kelz et al. 1999). The current results demonstrate that mating-induced c-Fos levels were reduced by sexual experience in brain areas with increased ΔFosB (NAc and ACA). The suppression of c-Fos appears dependent on the period since last mating and repeated mating sessions, as in previous studies, such a decrease in c-Fos was not detected in male rats tested 1 week following the final mating session (Balfour et al. 2004) or after sexual experience consisting of only a single mating session (Lopez & Ettenberg 2002). Moreover, the current finding is consistent with the evidence that ΔFosB represses the c-fos gene after chronic amphetamine exposure (Renthal et al. 2008). In line with these findings, the induction of several immediate early gene mRNAs (c-fos, fosB, c-jun, junB, and zif268) was reduced following repeated cocaine injections in comparison to acute drug injections (Hope et al. 1992; Hope et al. 1994), and amphetamine-induced c-fos was suppressed following withdrawal from chronic amphetamine administration (Jaber et al. 1995; Renthal et al. 2008). The functional relevance of the down-regulation of c-Fos expression after chronic drug treatment or sexual experience remains unclear, and has been suggested to be an important homeostatic mechanism to regulate an animal’s sensitivity to repeated reward exposure (Renthal et al. 2008).

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that ΔFosB in the NAc plays an integral role in sexual reward memory, supporting the possibility that ΔFosB is important for general reward reinforcement and memory. The findings from the current study further elucidate our understanding of cellular and molecular mechanisms that mediate sexual reward and motivation, and add to a body of literature showing that ΔFosB is an important player in development of addiction, by demonstrating a role for ΔFosB in natural reward reinforcement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to LMC, National Institute of Mental Health to EJN, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to KKP and LMC.

REFERENCES

- Agmo A. Male rat sexual behavior. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 1997;1:203–209. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(96)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmo A, Berenfeld R. Reinforcing properties of ejaculation in the male rat: role of opioids and dopamine. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104:177–182. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang E, Chen J, Zagouras P, Magna H, Holland J, Schaeffer E, Nestler EJ. Induction of nuclear factor-kappaB in nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine administration. J Neurochem. 2001;79:221–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfour ME, Yu L, Coolen LM. Sexual behavior and sex-associated environmental cues activate the mesolimbic system in male rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:718–730. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb JA, Chen J, Taylor JR, Svenningsson P, Nishi A, Snyder GL, Yan Z, Sagawa ZK, Ouimet CC, Nairn AC, Nestler EJ, Greengard P. Effects of chronic exposure to cocaine are regulated by the neuronal protein Cdk5. Nature. 2001;410:376–380. doi: 10.1038/35066591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KC, Haas AR, Meisel RL. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesions in female hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) abolish the sensitized effects of sexual experience on copulatory interactions with males. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:224–232. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KC, Meisel RL. Sexual behavior induction of c-Fos in the nucleus accumbens and amphetamine-stimulated locomotor activity are sensitized by previous sexual experience in female Syrian hamsters. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2123–2130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02123.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carle TL, Ohnishi YN, Ohnishi YH, Alibhai IN, Wilkinson MB, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Proteasome-dependent and -independent mechanisms for FosB destabilization: identification of FosB degron domains and implications for DeltaFosB stability. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3009–3019. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J, Nestler EJ. Molecular neurobiology of drug addiction. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:113–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Nye HE, Kelz MB, Hiroi N, Nakabeppu Y, Hope BT, Nestler EJ. Regulation of delta FosB and FosB-like proteins by electroconvulsive seizure and cocaine treatments. Molecular pharmacology. 1995;48:880–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CR, Whisler K, Steffen C, Nestler EJ, Self DW. Striatal cell type-specific overexpression of DeltaFosB enhances incentive for cocaine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2488–2493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolen LM, Allard J, Truitt WA, Mckenna KE. Central regulation of ejaculation. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsma G, Pfaus JG, Wenkstern D, Phillips AG, Fibiger HC. Sexual behavior increases dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens and striatum of male rats: comparison with novelty and locomotion. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:181–191. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz DM, Maze I, Mechanic M, Vialou V, Dietz KC, Iniguez SD, Laplant Q, Russo SJ, Ferguson D, Nestler EJ. Essential role for ΔFosB in cocaine regulation of dendritic spines of nucleus accumbens neurons. Society for Neuroscience Abstract. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Frohmader KS, Pitchers KK, Balfour ME, Coolen LM. Mixing pleasures: Review of the effects of drugs on sex behavior in humans and animal models. Horm Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.11.009. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges VL, Chakravarty S, Nestler EJ, Meisel RL. Delta FosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens enhances sexual reward in female Syrian hamsters. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:442–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez L, Hoebel BG. Feeding and hypothalamic stimulation increase dopamine turnover in the accumbens. Physiol Behav. 1988a;44:599–606. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez L, Hoebel BG. Food reward and cocaine increase extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens as measured by microdialysis. Life Sci. 1988b;42:1705–1712. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi N, Marek GJ, Brown JR, Ye H, Saudou F, Vaidya VA, Duman RS, Greenberg ME, Nestler EJ. Essential role of the fosB gene in molecular, cellular, and behavioral actions of chronic electroconvulsive seizures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6952–6962. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06952.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommel JD, Sears RM, Georgescu D, Simmons DL, DiLeone RJ. Local gene knockdown in the brain using viral-mediated RNA interference. Nat Med. 2003;9:1539–1544. doi: 10.1038/nm964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope B, Kosofsky B, Hyman SE, Nestler EJ. Regulation of immediate early gene expression and AP-1 binding in the rat nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5764–5768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Nye HE, Kelz MB, Self DW, Iadarola MJ, Nakabeppu Y, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Induction of a long-lasting AP-1 complex composed of altered Fos-like proteins in brain by chronic cocaine and other chronic treatments. Neuron. 1994;13:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull EM, Meisel RL, Sachs BD. Male Sexual Behavior. Horm Behav. 2002;1:1–139. [Google Scholar]

- Jaber M, Cador M, Dumartin B, Normand E, Stinus L, Bloch B. Acute and chronic amphetamine treatments differently regulate neuropeptide messenger RNA levels and Fos immunoreactivity in rat striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 1995;65:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00537-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WJ, Becker JB. Dynamic increases in dopamine during paced copulation in the female rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1997–2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Chen J, Carlezon WA, Jr, Whisler K, Gilden L, Beckmann AM, Steffen C, Zhang YJ, Marotti L, Self DW, Tkatch T, Baranauskas G, Surmeier DJ, Neve RL, Duman RS, Picciotto MR, Nestler EJ. Expression of the transcription factor deltaFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401:272–276. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez HH, Ettenberg A. Exposure to female rats produces differences in c-fos induction between sexually-naive and experienced male rats. Brain Res. 2002;947:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02907-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maze I, Covington HE, 3rd, Dietz DM, LaPlant Q, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Mechanic M, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Haggarty SJ, Ren Y, Sampath SC, Hurd YL, Greengard P, Tarakhovsky A, Schaefer A, Nestler EJ. Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science. 2010;327:213–216. doi: 10.1126/science.1179438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Regulation of gene expression and cocaine reward by CREB and DeltaFosB. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/nn1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Ulery PG, Perrotti LI, Zachariou V, Berton O, Nestler EJ. DeltaFosB: a molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;132:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Lonstein JS. Dopaminergic projections to the medial preoptic area of postpartum rats. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1384–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JI, Curran T. Stimulus-transcription coupling in neurons: role of cellular immediate-early genes. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:459–462. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47 Suppl 1:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. The neurobiology of cocaine addiction. Sci Pract Perspect. 2005;3:4–10. doi: 10.1151/spp05314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Review. Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: role of DeltaFosB. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3245–3255. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11042–11046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HE, Hope BT, Kelz MB, Iadarola M, Nestler EJ. Pharmacological studies of the regulation of chronic FOS-related antigen induction by cocaine in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1671–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Tronson N, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR. DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens regulates food-reinforced instrumental behavior and motivation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9196–9204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakman MC, Colby C, Perrotti LI, Tekumalla P, Carle T, Ulery P, Chao J, Duman C, Steffen C, Monteggia L, Allen MR, Stock JL, Duman RS, McNeish JD, Barrot M, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Schaeffer E. Inducible, brain region-specific expression of a dominant negative mutant of c-Jun in transgenic mice decreases sensitivity to cocaine. Brain Res. 2003;970:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Bolanos CA, Choi KH, Russo SJ, Edwards S, Ulery PG, Wallace DL, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Barrot M. DeltaFosB accumulates in a GABAergic cell population in the posterior tail of the ventral tegmental area after psychostimulant treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2817–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Hadeishi Y, Ulery PG, Barrot M, Monteggia L, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Induction of deltaFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10594–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2542-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Weaver RR, Robison B, Renthal W, Maze I, Yazdani S, Elmore RG, Knapp DJ, Selley DE, Martin BR, Sim-Selley L, Bachtell RK, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Distinct patterns of DeltaFosB induction in brain by drugs of abuse. Synapse. 2008;62:358–369. doi: 10.1002/syn.20500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG. Pathways of sexual desire. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1506–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG, Kippin TE, Centeno S. Conditioning and sexual behavior: a review. Horm Behav. 2001;40:291–321. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AG, Vacca G, Ahn S. A top-down perspective on dopamine, motivation and memory. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:236–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Balfour ME, Lehman MN, Richtand NM, Yu L, Coolen LM. Neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic system induced by natural reward and subsequent reward abstinence. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal W, Carle TL, Maze I, Covington HE, 3rd, Truong HT, Alibhai I, Kumar A, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, Nestler EJ. Delta FosB mediates epigenetic desensitization of the c-fos gene after chronic amphetamine exposure. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7344–7349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1043-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal W, Kumar A, Xiao G, Wilkinson M, Covington HE, 3rd, Maze I, Sikder D, Robison AJ, LaPlant Q, Dietz DM, Russo SJ, Vialou V, Chakravarty S, Kodadek TJ, Stack A, Kabbaj M, Nestler EJ. Genome-wide analysis of chromatin regulation by cocaine reveals a role for sirtuins. Neuron. 2009;62:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenk CM, Wilson H, Zhang Q, Pitchers KK, Coolen LM. Sexual reward in male rats: effects of sexual experience on conditioned place preferences associated with ejaculation and intromissions. Horm Behav. 2009;55:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulery-Reynolds PG, Castillo MA, Vialou V, Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. Phosphorylation of DeltaFosB mediates its stability in vivo. Neuroscience. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulery PG, Rudenko G, Nestler EJ. Regulation of DeltaFosB stability by phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5131–5142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DL, Vialou V, Rios L, Carle-Florence TL, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Graham DL, Green TA, Kirk A, Iniguez SD, Perrotti LI, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Nestler EJ, Bolanos-Guzman CA. The influence of DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens on natural reward-related behavior. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10272–10277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1531-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werme M, Messer C, Olson L, Gilden L, Thoren P, Nestler EJ, Brene S. Delta FosB regulates wheel running. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8133–8138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08133.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, LaPlant Q, Theobald DE, Green TA, Bachtell RK, Perrotti LI, DiLeone RJ, Russo SJ, Garth WJ, Self DW, Nestler EJ. DeltaFosB induction in orbitofrontal cortex mediates tolerance to cocaine-induced cognitive dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10497–10507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2566-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V, Bolanos CA, Selley DE, Theobald D, Cassidy MP, Kelz MB, Shaw-Lutchman T, Berton O, Sim-Selley LJ, Dileone RJ, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. An essential role for DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nn1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang L, Jiao H, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Lou D, Katz JL, Xu M. c-Fos facilitates the acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced persistent changes. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13287–13296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.