Abstract

This study formulates a theory for multigenerational interstitial growth of biological tissues whereby each generation has a distinct reference configuration determined at the time of its deposition. In this model, the solid matrix of a growing tissue consists of a multiplicity of intermingled porous permeable bodies, each of which represents a generation, all of which are constrained to move together in the current configuration. Each generation’s reference configuration has a one-to-one mapping with the master reference configuration, which is typically that of the first generation. This mapping is postulated based on a constitutive assumption with regard to that generations’ state of stress at the time of its deposition. For example, the newly deposited generation may be assumed to be in a stress-free state, even though the underlying tissue is in a loaded configuration. The mass content of each generation may vary over time as a result of growth or degradation, thereby altering the material properties of the tissue. A finite element implementation of this framework is used to provide several illustrative examples, including interstitial growth by cell division followed by matrix turnover.

Keywords: Biological growth, Mixture theory, Residual stress, Reference configuration, Cell division

1 Introduction

Biological tissue growth is a process driven by chemical reactions among various fluid and solid constituents of a mixture. For example, a cell may use amino acids that are present in a culture environment to build a protein and release it into the extracellular space; this protein subsequently may bind to the extracellular matrix, increasing its mass. In this example, amino acids are considered to be fluid constituents (solutes in solution), whereas the extracellular matrix is considered to be the solid constituent. Thus, growth alludes to changes in the mass of the solid matrix of the mixture as a result of mass exchanges with the fluid constituents. For porous mixtures, this mass exchange may occur in the interstitial space of the solid matrix (Cowin and Hegedus 1976), through which the fluid constituents may flow. Therefore, such processes are described as interstitial growth, or equivalently, volumetric growth.

Fundamentally, interstitial growth is a process by which mass is deposited or removed from the interstitial space of a mixture. This process can be described by the equation of balance of mass, taking into account mass exchanges among various constituents. Therefore, a natural framework for describing growth of biological tissues is the theory of mixtures, which may account for any number of fluid and solid constituents in a continuum analysis. Mixture theory encompasses the classical frameworks of solid and fluid mechanics, and its formulation may be generalized to account for chemical reactions among the constituents (Truesdell and Toupin 1960; Bowen 1968, 1969; Ateshian 2007).

Mathematical growth theories must be cognizant of the underlying mechanisms responsible for growth in the physical world. Growth of non-living systems is simpler to model than growth of living systems. Non-living systems experience large mass deposition mostly in the form of appositional, or surface growth. For example, stalactites and stalagmites may grow very large as mineral-laden water flows over them, leading to slow deposition of mass onto the underlying solid structure; similarly, volcanoes grow in size as molten lava solidifies in successive layers over each other. Interstitial growth of a non-living system is typically much more limited in scope, since it can proceed only until the interstitial space has been filled. For example, porous filters experience growth in mass as their pores progressively clog with retentate; this process ends when all the pores have been filled, yet the external dimensions of the filter may not have changed significantly.

In contrast, interstitial growth in biological systems can produce very large increases in mass and volume over time, as evidenced by the growth of an embryo into a full-size adult human being. This process occurs primarily as a result of cell division. In a recent study (Ateshian et al. 2009), we demonstrated that biological growth by cell division can be modeled within the framework of mixture theory by describing the interstitial growth of intracellular solid matrix constituents and membrane-impermeant solutes. Since the cell membrane is semi-permeable, an intracellular increase in these constituents by uptake of solutes from the extracellular bathing solution drives water into the cell via osmotic mechanisms during its synthesis phase. This water uptake doubles the cell volume, a process needed to produce two nearly identical daughter cells during mitosis. With repeated cell division, the volume of the tissue can increase with no theoretical upper limit, unlike the case of interstitial growth in non-living systems, because the osmotic swelling accompanying growth guarantees that the interstitial space will continually expand and never be filled.

This concept of growth by cell division reinforces the need to derive mathematical models that are consistent with the underlying physical processes. However, regardless whether interstitial growth occurs by cell division or more prosaic processes, another challenge of growth theories centers on the concept of the reference configuration of the newly deposited solid matrix. In classical solid mechanics of non-reactive systems, where the mass of the body remains constant, it is common to posit a stress-free reference configuration from which the analysis of deformation may proceed. In a growing body, however, no consensus has yet emerged on the manner by which reference configurations should be identified, though many alternatives have been proposed (Rodriguez et al. 1994; Klisch et al. 2001; Humphrey and Rajagopal 2002; Volokh and Lev 2005; Guillou and Ogden 2006; Ateshian 2007).

The objective of this study is to formulate a theory for multigenerational interstitial growth of biological tissues (and non-living systems), whereby each generation has a distinct reference configuration determined at the time of its deposition. In this model, the solid matrix of a growing tissue consists of a multiplicity of intermingled bodies, each of which represents a generation, all of which are constrained to move together in the current configuration. This proposed framework builds on the concept of constrained mixtures of solids originally formulated by Humphrey and Rajagopal (2002). The main distinction with the approach of these authors is that they treat the growing tissue as a mixture of different materials each having an evolving reference configuration, whereas the current approach considers the tissue as a mixture of constrained bodies representing multiple generations of material deposition, each with its own invariant reference configuration.

The specific aim is to determine the form of constitutive relations for the solid constituents of a multigenerational tissue based on constraints from the Clausius-Duhem inequality, to clarify which equations of linear momentum are sufficient to describe the motion of the constrained solids and unconstrained fluids in a biological tissue mixture and to provide illustrations that address fundamental problems in growth theory.

2 Mixture of fluids and constrained solids

The detailed derivation of a mixture framework where the tissue consists of multiple fluid and solid constituents, and where the solids are constrained to move together in the current configuration, even though they may have distinct reference configurations, is given in the Appendix. The derivation appeals to the balance axioms of mass, momentum and energy, and proposes constitutive formulations consistent with the axiom of entropy inequality. Though the detailed derivation is relatively involved, the final governing equations for a mixture of fluids and constrained solids are remarkably simple. Since all the solid constituents are constrained to move together, there is neither the need nor the possibility to solve for the conservation of linear momentum for each solid constituent. The balance of linear momentum for the entire mixture may be used instead; when neglecting inertia and external body forces, this produces the familiar expression

| (1) |

where T is the mixture stress. When neglecting dissipative stresses (such as viscous stresses in the solids and fluids), and the contribution of diffusion velocities, and under the assumption that the mixture satisfies electroneutrality (see Appendix),

| (2) |

where σ denotes each of the solid constituents, and Fσ is its deformation gradient relating the current configuration x = χσ (Xσ, t) to the reference configuration Xσ for that body, Fσ = ∂χσ /∂Xσ. Since there are multiple solids constrained to move together, we may denote one of the solid constituents with σ = s and use it as a master reference configuration. Then, Js = det Fs is the relative volume of the mixture when evaluated with respect to that reference configuration, and W is the Helmholtz free energy density for the mixture (denoted by in the Appendix), representing the free energy per unit volume of the mixture in the reference configuration Xs. p represents the interstitial fluid pressure and arises from the assumption that all fluid and solid constituents are intrinsically incompressible; however, since the mixture is porous and permeable, it may gain or lose volume as fluid enters or leaves a material region defined on the solid matrix (thus Js ≠ 1 under general conditions).

Since there can be multiple unconstrained fluid constituents in the mixture (such as multiple solutes in a solvent), each fluid must satisfy its own equation of conservation of linear momentum; when neglecting inertia, external body forces and dissipative stresses (such as viscous stresses), and under isothermal conditions, this equation reduces to

| (3) |

where ρι is the apparent density of fluid constituent ι, μ̃ι is its mechano-electrochemical potential, and represents the dissipative part of the momentum supply to constituent ι from all other constituents in the mixture; most commonly, models the frictional interactions among the constituents.

The state variables for W may be given by

| (4) |

where θ is the absolute temperature, is the apparent density of solid constituent σ relative to the mixture volume in the reference configuration Xσ, and is the apparent density of fluid constituent ι relative to the mixture volume in the reference configuration Xs. Since all the solids are constrained to move together in the current configuration, it follows that

| (5) |

for all σ, even though the reference configurations Xσ are distinct. Thus, the reference configurations of the various solid constituents may be related to the master reference configuration via

| (6) |

where Fσs = ∂Xσ /∂Xs is a time-invariant transformation.

We may now define the effective stress tensor for each solid constituent as

| (7) |

such that it has the standard form for a hyperelastic solid. Importantly, it should be understood that is evaluated using that constituent’s Fσ (or any other related strain measure, such as the right or left Cauchy-Green tensors, Cσ = (Fσ)T · Fσ and Bσ = Fσ · (Fσ)T). Therefore, the mixture stress may be rewritten as

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

is a time-invariant quantity, and is the effective stress for the mixture.

Example 1

Consider a 1-D analysis where the constitutive relation for is that of a linear spring, , where kσ is the spring modulus and λσ is the stretch ratio for solid (spring) σ; note that Jσ = λσ in this case. Also assume that the fluid pressure has subsided, p = 0. For a homogeneous deformation, we may write λσ = x/Xσ, where Xσ is the reference position for material points in solid σ. Consider that a traction f is applied on the mixture of two solids (σ = 1, 2); then according to (Eq. 8), if we pick Xs to coincide with X(1),

| (a) |

where

| (b) |

It is important to keep in mind that material points X(1) in solid (1) and X(2) in solid (2) are constrained to move together, so that the ratio X(2)/X(1) for each constrained pair is constant, and their current position is given by x. The result for k(e) illustrates the fact that intermingled solids act as springs in parallel, since their moduli sum up. In this example, because the deformations are homogeneous, it is possible to represent the solid as a spring with modulus k(e) and equivalent reference configuration X(e).

Growth of the solid constituents is described by changes in as a result of chemical reactions that add mass to, or remove it from, constituent σ. According to the axiom of balance of mass (see Bowen 1969; Guillou and Ogden 2006; Ateshian 2007; Ateshian et al. 2009 and Appendix), when expressing in a material frame, , it satisfies

| (10) |

where is the mass supply to constituent σ from chemical reactions. This relation is easily integrated to produce

| (11) |

Note that is a material function that also depends on state variables such as those described in (Eq. A.34), and this dependence must be described by experimentally validated constitutive relations. Clearly, in the absence of growth, and the apparent density remains invariant, in which case it would no longer be needed as a state variable for W in (Eq. 4). More generally, this mixture formulation distinguishes the effects of deformation from growth by letting W depend on Fσ and . Though changes in may influence deformation (e.g., via osmotic alterations in the pressure p), and Fσ are independent state variables.

3 Multigenerational interstitial growth

The basic framework of multigenerational interstitial growth advocated in this study is that new solid mass deposited within the interstitial space of tissue T, in a reference configuration that differs from previously deposited mass, belongs to a new body Bσ, which is intermingled with the bodies from earlier time points, such that all are constrained to move together. Consistent with the above presentation of mixtures of constrained solids, the body Bσ is represented by solid σ, and its reference configuration is Xσ. Since solid mass may be deposited over a continuous time spectrum, there may be an infinite number of bodies Bσ representing the tissue. In the treatment adopted here, we consider that mass being deposited with a common reference configuration over the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1 belongs to the same generation. Thus, we refer to material deposited during this time interval as the σ–th generation, also known as the body Bσ. The span of time intervals for each generation is entirely guided by the specific growth problem of interest, and there is no requirement or expectation that these intervals be of uniform length.

While all the bodies Bσ share the same domain as the tissue T, their mass content and distribution, given by , will generally be different. By definition, the growth of body Bσ implies that increases from zero over the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1; however, some regions of T may nevertheless have . Indeed, the mass content, and thus the material properties, of Bσ may be inhomogeneous and evolve over time.

It follows that a growing tissue that has entered its γ-th generation consists of a total of γ bodies, B1, B2, …, Bγ. We may refer to the collection of these intermingled bodies as the tissue in its γ-th generation, Tγ. In the continuum representation of the tissue, all these bodies co-exist within an elemental material region of Tγ, though the mass content of each generation may vary over time and even reduce to zero. Indeed, it is also important to recognize that each generation’s Bσ may lose mass over time due to degradative processes; thus, the deposition of mass sharing a common reference configuration defines a new generation or body in the tissue, but degradation could possibly lead to the total loss (solubilization) of the mass content of a particular generation, equivalent to at some time t > tσ.

Each body Bσ has its own stress-free reference configuration Xσ, which has a one-to-one mapping with the master generation Xs, see (Eq. 6); normally, the most appropriate choice for Xs is the first generation (σ = 1). Importantly, this mapping exists at every location Xs, even if the mass content of Bσ at that point happens to be zero. The existence of this mapping is guaranteed by the fact that the reference configuration Xσ is posited by constitutive assumptions, typically guided by ambient conditions prevailing during the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1. Therefore, the mapping does not depend on the current value of .

For example, we may assume that mass deposited in the interstitial space over the time interval time tσ ≤ t < tσ+1 is in a stress-free state, even though the underlying pre-existing tissue Tσ−1 is in a loaded state. Thus, we may set Xσ = x (Xs, tσ), or equivalently, Fσs = Fs (Xs, tσ). In other words, the reference configuration of mass deposited in the σ-th generation coincides with the current configuration of the tissue at the start of the generation. This is the simplest non-trivial example of a constitutive assumption for determining the reference configuration of Bσ, though it may well be generally valid for most of the biological tissue growth problems. Other assumptions may be similarly adopted, such that the newly deposited mass is not in a stress-free state at tσ, though such constitutive assumptions might require an inverse solution to determine the reference configuration from the assumed state of stress at the time of mass deposition.

Most importantly, the reference configuration Xσ is invariant. Thus, even though Bσ may be gaining mass over the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1, the reference configuration Xσ does not evolve because, we have defined this time interval to represent mass deposition under the common reference configuration Xσ. For example, if we assume constitutively that Xσ = x (Xs, tσ), it is implied that tissue deformation remains unchanged (or nearly so) over the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1. Therefore, this assumption also guides the length of this time interval based on the prevailing loading conditions.

The material properties of Bσ depend on its mass content , as well as the mass content of all the other solid bodies (and fluid constituents) in the tissue, as is evident from (Eqs. 4 and 7); the precise form of this dependence needs to be provided by constitutive relations. This dependency is expected on physical grounds as well, since the bodies Bσ are porous and the material properties represent those of the porous structure, not the intrinsic properties of the skeleton material. For example, a porous solid matrix consisting of type II collagen will have different properties depending on whether its porosity is 20 or 90%, even though collagen fibrils in the two cases have identical intrinsic properties. This is rooted in the fact that stress tensors in mixture theory are apparent stresses. Indeed, just as the apparent densities represent mass per unit volume of the mixture, the apparent stresses have components that represent force per unit area of the mixture (not per unit area of a particular constituent in the mixture). This makes it possible to sum up the stresses of the various constituents in a consistent manner.

The mass density represents mass per unit volume of Bσ in its reference configuration. When tracking growth and resorption of all solid constituents, there may be circumstances where it is more convenient to use the master reference configuration Xs to represent the mass content of each body,

| (12) |

This relation shows that are related by the time-invariant factor Jσs.

Finally, it should be noted that body Bσ may itself consist of more than one solid species; for example, in articular cartilage growth, chondrocytes may synthesize type II collagen and proteoglycans simultaneously, both of which contribute to its solid matrix, and it may be constitutively assumed that these constituents are being deposited in a common reference configuration over the time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1. Thus, solid σ may itself be a mixture of constrained solids, all sharing the same reference configuration. Conversely, if a constitutive assumption is made that solid constituents deposited over the same time interval tσ ≤ t < tσ+1 have different reference configurations, they may be considered to belong to different, though, overlapping generations, for the purpose of mathematical treatment. The generalization of the notation adopted in the above equations for these two cases is straightforward.

4 Examples

4.1 Finite element implementation

A finite element implementation of multigenerational growth of constrained solids was developed based on a pre-existing custom code for growth of a single generation (Ateshian et al. 2009). The user specifies the number of generations and their starting time tσ in the input file; during the solution steps, the code automatically stores the current configuration x (Xs, tσ) at the start of each generation and assigns it to Xσ, so that Fσ may be subsequently evaluated for that generation. Any desired number of solid constituents may be assigned to each generation, each solid having its own constitutive relation. Furthermore, material properties for each solid may be prescribed to vary over time, to account for their alteration with growth. The code also accommodates osmotic alterations in the fluid pressure p as a result of cell division, growth of charged extracellular solid matrix constituents and other forms of osmotic loading (Ateshian et al. 2009). This code was used for all the examples illustrated below. Relatively large loads are applied in these examples to produce visibly large deformations for ease of interpretation. The constitutive relation adopted for the solid matrix is the isotropic, compressible, hyperelastic formulation of Holmes and Mow (1990), whose material properties are Lamé-like constants λs and μs and an exponential stiffening coefficient β. Compressibility is the expected behavior of porous solids, even if their skeleton is intrinsically incompressible, because pores need not preserve their volume under loading.

4.2 Cantilever beam

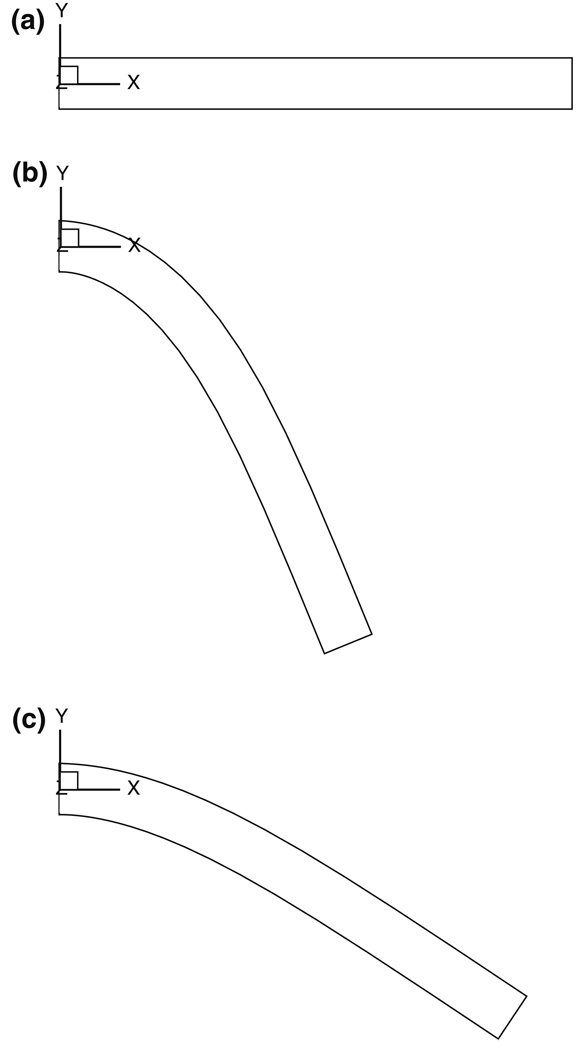

Consider a cantilever beam T (10 × 1 × 1 mm) consisting of a single porous elastic solid B1 in its first generation (λs = 0, μs = 0.5 MPa, β = 0.1). Assume that there are no osmotic effects in this problem, so that p = 0 at steady state. The beam is straight in its unloaded configuration (Fig. 1a). Upon loading with a uniformly distributed transverse load (−0.01 N resultant along Y), the beam deflects as expected (Fig. 1b), and the net effective stress in the beam is that of B1, . Now let a second generation B2 grow into T while it remains subjected to the transverse load. For convenience, B2 is given the same constitutive relation and material properties as B1. Since B2 is growing in a stress-free state, , there will be no alteration in the current configuration of T as a result of this growth (Fig. 1b); thus, . If the transverse load is now removed, the beam will recover only partially (Fig. 1c), because the effective stresses in B1 and B2 compete to produce a non-zero effective stress in the unloaded beam, even though ∇ · Te = 0 according to the mixture balance of momentum (Fig. 2). This example illustrates how growth can alter the unloaded state of a tissue and produce residual stresses in it.

Fig. 1.

Growth of a cantilever beam. a Stress-free reference configuration of T1 (first generation). b Loaded configuration of T1, also loaded configuration of T2, following growth of second generation. c Unloaded (residually stressed) configuration of T2

Fig. 2.

Effective normal stress distribution Txx at fixed end of cantilever beam

4.3 Thick-walled tube

This example addresses a classical problem in the study of growth and residual stresses in arteries (Taber and Humphrey 2001). Consider a similar problem where a thick-walled tube T (inner radius Ri = 0.5 mm, outer radius Ro = 1.0 mm), initially in its first generation (B1 with λs = 0, μs = 0.5 MPa, β = 0.5) under a stress-free state, is subjected to an internal pressure (1 MPa). Consider three possible alternatives for growth: in case 1, growth of B2 (same material properties as B1) occurs only in the inner rim of the wall (Ri ≤ R ≤ (Ri + Ro) /2, Fig. 3); in case 2, B2 grows only in the outer rim (Fig. 4); and in case 3, it grows throughout the wall thickness (Fig. 5). When growth ends, T is unloaded and returns to a residually stressed state, which produces a different distribution of Te in each case (Fig. 6). Now cut the tube radially at the bottom end, and in each case, the tube takes on a different, residually stressed, unloaded state: in case 1, the tube exhibits a positive opening angle (Fig. 3d), whereas in cases 2 (Fig. 4d) and 3 (Fig. 5d), it produces a negative opening angle, though much more pronounced in the former case. This example is illustrative of a potential mechanism by which residual stresses may be produced in the arterial wall. As inferred from experimental observations by previous investigators (Vossoughi et al. 1993; Greenwald et al. 1997), a radial cut in the residually stressed unloaded tube does not relieve the residual stresses (Fig. 6); in these examples, upon cutting, residual stresses come closest to a uniform zero value only in the case of homogeneous growth (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 3.

Thick-walled tube, growth in inner rim only; due to symmetry, only the right side of the tube is modeled. a T1 in stress-free configuration. b T1 (and T2) with internal pressurization. c T2 in unloaded configuration. d T2 in unloaded configuration, after radial cut; the opening angle is positive

Fig. 4.

Thick-walled tube, growth in outer rim only. a T1 in stress-free configuration. b T1 (and T2) with internal pressurization. c T2 in unloaded configuration. d T2 in unloaded configuration, after radial cut; the opening angle is negative

Fig. 5.

Thick-walled tube, homogeneous growth. a T1 in stress-free configuration. b T1 (and T2) with internal pressurization. c T2 in unloaded configuration. d T2 in unloaded configuration, after radial cut; the opening angle is negative

Fig. 6.

Radial distribution of residual circumferential normal effective stress at apex (Θ = π/2), for thick-walled tube in its second generation (T2) unloaded configuration, before and after radial cut. a Inner rim growth; b outer rim growth; c homogeneous growth

4.4 Multigenerational growth by cell division and matrix turnover

In this last example, we consider multigenerational growth by cell division. As described in our recent study (Ateshian et al. 2009), in order for a cell to divide into two nearly identical daughter cells, it must double its mass content; this is achieved during the synthesis phase by doubling the content of the intracellular solid matrix (denoted by ) and intracellular membrane-impermeant solutes (), which produces a doubling of the water content via passive osmotic uptake. When considering a multitude of cells, it is not necessary to constrain the analysis to discrete jumps in cell number, and growth by cell division may be simply described by the mass supplies as smooth functions of time. For simplicity, we assume that the extracellular matrix (ECM) is of neutral charge and that the water content of the ECM and intracellular space is the same; furthermore, consider that the external bathing solution of the tissue consists predominantly of NaCl at a concentration c* that remains isotonic; then, the osmotic pressure in the homogenized tissue (comprised of cells and ECM) is simply given by

where p* is the ambient pressure in the bath (typically taken as p* = 0), R is the universal gas constant, χ is the volume fraction of cells in the tissue, and is the concentration of intracellular membrane-impermeant solute in the current configuration, evaluated on a solution volume basis. Based on the standard relation between concentration (on a solution volume basis) and apparent density (on a mixture volume basis), it can be shown that

where is the molecular weight of intracellular solutes, and is the true density of the intracellular solid matrix. The evolution of with growth is given by (Eq. 11). Furthermore, as cells divide, the volume fraction of cells in the tissue may evolve according to

| (13) |

where ξ is the ratio of cell volume to ECM volume, related to χ via

| (14) |

and ξ̂ represents the rate at which this volume ratio increases. For cell division (or apoptosis), it is expected that the following growth rates be proportional to each other,

| (15) |

Let us now consider an example where the first generation B1 of a tissue T consists of a clump of cells in a stress-free state at time t = t1; the shape of this clump is arbitrary and will be preserved if we assume that growth rates are homogeneous throughout the clump (in the finite element analysis, any shape may be adopted, including the simplest case of a single brick element). Assume that the ECM solids and fluids occupy 20% of the tissue volume (χ = 0.8, ξ = 4) and that the cells have negligible stiffness; for the ECM, let λs = 0, μs = 5 kPa and β = 0.1. Let growth proceed by cell division such that and ξ increase by a factor of 100 at time t = t2; no ECM growth is assumed to occur over this time span. The tissue is still in its first generation, because there is no need to define a new reference configuration during this growth stage, owing to the fact that the solid matrix of cells has negligible stiffness. As seen in Fig. 7, the tissue volume has now increased by a factor of Js = 88.5, a value that depends significantly on the elastic properties of the ECM, since it is now in a swollen, stressed state balanced by an increase in the interstitial osmotic pressure p to 124 kPa (Fig. 7). Indeed, for this case of homogeneous growth under traction-free conditions, T = 0 at all times, so that the effective residual stress is given by Te = pI. Now consider that there is turnover of the ECM, which we model in two steps: first, the ECM of B1 progressively degrades (its elastic moduli are reduced to zero) over the time interval t2 ≤ t < t3; as a result of this degradation, the resistance to the osmotic expansion progressively decreases, so that the osmotic pressure reduces to zero; and the tissue volume reaches 100 times its original volume at t3 (Fig. 7), consistent with the 100-fold increase in the number of cells embodied in the equivalent increases in . In the second stage of this turnover, a new ECM is synthesized, forming a second generation B2 whose reference configuration is X(2) = x (X(1), t3). This process occurs over the time interval t3 ≤ t < t4, during which there is no further change in tissue volume (Js = 100) or interstitial osmotic pressure (p = 0).

Fig. 7.

Growth by cell division, followed by matrix turnover. Js indicates the relative change in volume of T over time; p is the interstitial fluid pressure

Because we idealized the turnover process to occur such that the second generation is deposited only after the ECM of the first generation has completely resorbed, there is no residual stress in the solid matrix of the tissue at the end of this growth process. The deposition of ECM did not produce any obligatory change in volume, as illustrated in the growth of B2 from t3 to t4. Instead, the tissue relative volume Js increased as a result of cell division from t1 to t2 and as a result of matrix degradation from t2 to t3.

Clearly, many other illustrative sequences of growth may be conjured, which may lead to different outcomes with regard to residual stresses. Evidently, the matrix turnover process need not be assumed to occur over two consecutive steps of old matrix degradation followed by new matrix deposition, as these processes may occur concurrently. Such concurrent processes may be idealized in the above framework by modeling multiple generations over smaller time increments, and allowing new matrix deposition to occur prior to the complete degradation of older matrix generations. The availability of a computational framework facilitates such analyses considerably.

5 Discussion

The main objective of this study was to demonstrate that interstitial growth may be modeled as the successive deposition of porous solids, each having its own reference configuration, thus defining a growth generation. All the intermingled generations are constrained to move together in the current configuration (Humphrey and Rajagopal 2002). This approach represents a fundamental framework for interstitial growth, cognizant of the fact that growth represents a process of mass deposition and removal from the tissue solid matrix, as a result of chemical reactions involving solutes in solution in the interstitial pore space.

In this approach, it is implicit that the resulting tissue can experience interstitial growth only until its interstitial space has filled; for biological tissues, however, the interstitial space need never fill, because the growth of intracellular solid and solute constituents accompanying cell division produces an osmotic driving force that continually swells the tissue, preventing filling of that space (Ateshian et al. 2009). This mechanism was illustrated in an example where the number of cells increased 100-fold as a result of cell division (Fig. 7).

This study also demonstrates that the state of residual stress in a growing tissue may be predicted in a straightforward manner when its growth history is known, as illustrated in the case of the cantilever beam (Fig. 2) and the thick-walled cylinder (Fig. 6). As demonstrated in the case of the unloaded intact and unloaded radially cut thick-walled cylinder, traction-free configurations need not be stress-free because of persisting residual stresses induced during growth. Therefore, unless its growth history is known, there is no possibility of deducing the stress-free configuration of a grown tissue under general conditions.

The framework adopted in this study builds considerably on the concept of constrained mixtures of solids advanced by Humphrey and Rajagopal (2002) and reprised by other investigators (Wan et al. 2009). It differs from that original framework primarily by not using the concept of evolving natural (stress-free) configurations. These authors described their solid mixtures primarily on the basis of different material types (collagen, elastin and smooth muscle cells); in their approach, each of these materials may have a different growth history, and thus an associated evolving natural configuration. In the approach advocated in the current study, a given material (e.g., collagen) may itself consist of multiple solid constituents σ, each representing a generation produced during a particular growth spurt, and each having its own invariant stress-free reference configuration. When a tissue consists of multiple matrix types, each type may have multiple growth generations. An advantage of this approach is that each generation can be treated using the conventional kinematics of continua, where the reference configuration is stress-free and time-invariant.

A fundamental concept of this multigenerational growth framework is that the reference configuration of each generation is formulated with a constitutive assumption, guided by experimental observations of the manner by which new material gets deposited within the interstitial space of preceding generations. One such constitutive assumption, Xσ = x (Xs, tσ), was adopted for illustrative purposes in Sect. 3 and the examples of Sect. 4. Any number of alternative assumptions may be adopted, such as the simple choice Xσ = Xs, implying that the newly deposited material is under the same state of strain as the underlying material (thus, in a non-zero state of stress). This case will not produce residual stresses from multigenerational growth, and some physical mechanism would be needed to explain how newly deposited material can learn and reproduce the substrate’s state of strain. More elaborate assumptions may be formulated, such as the possibility that newly deposited molecules alter the surface energy of the substrate (at a microscopic scale) such that the deposited mass is not in a stress-free state once it binds to the substrate. Other mechanisms, such as electromagnetic forces, may similarly alter the state of stress of molecules being deposited unto the preceding generations. Such alternatives may be explored in future studies.

This framework differs more fundamentally from those of Skalak et al. (1982) and Rodriguez et al. (1994), who proposed that growth may be defined kinematically. In particular, Rodriguez et al. (1994) describe a growth model where the solid density remains constant, in contrast to the pore-filling interstitial growth mechanism described by Cowin and Hegedus (1976) and adopted here. In the current framework, growth is represented by temporal changes in , which is exclusively described by the equation of balance of mass, (Eq. 10), using the concept of the pullback of the solid density (Bowen 1969; Guillou and Ogden 2006; Ateshian 2007), (Eq. A.22). In this context, growth is not tied to deformation via an obligatory relation; thus, Fσ and are both needed as state variables in a growth framework, (Eq. 4). Indeed, the dependence of the Helmholtz free energy on the solid density is also needed to produce a relation consistent with the classical relation for the thermodynamic admissibility of chemical reactions, (Eq. A.41), which involves the chemical potential of all solid and fluid constituents of a mixture.

In the phenomenological growth framework proposed by Guillou and Ogden (2006), the deformation gradient F of the solid may be decomposed into F = Fe · Fr, where Fr is the transformation from the stress-free reference configuration (ℬ0) to the residually stressed, traction-free configuration following growth (ℬr), and Fe represents the deformation relative to ℬr as a result of loading in the current configuration (ℬt). In this context, ℬr (which is not a stress-free configuration) may evolve due to growth, and indeed, the example of the thick-walled cylinder given above illustrates how ℬr differs from ℬ0 (compare Fig. 3a, c, and note the residual stresses in the uncut tube in Fig. 6a). Therefore, the approach presented in the current study provides a method by which ℬr may be obtained for the purpose of using the framework of Guillou and Ogden, given knowledge of the growth process.

From our perspective, this study extends our recent presentation of interstitial growth by cell division, regulation of intracellular solute content and deposition of charged ECM constituents (Ateshian et al. 2009), where it had been assumed that all solid constituents belonged to the same growth generation. These combined studies provide a comprehensive modeling framework for interstitial growth of biological tissues. They recognize that growth is a result of chemical reactions; therefore, constitutive relations are needed to relate chemical reactions to the state variables in an analysis. The formulation of such constitutive relations ties the growth process to chemistry and biology; as usual, such formulations require experimental investigations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR46532), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM083925) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, as well as the Scientific Exchange Program of the University of Duisberg-Essen.

A Appendix

We begin by describing biological tissues as unconstrained mixtures of multiple solids and fluids. The concept of constrained intermingled bodies resulting from multigenerational growth will be addressed below. In mixture theory (Truesdell and Toupin 1960; Bowen 1976), multiple constituents α can co-exist within an elemental region, including solid and fluid constituents. In the current configuration, the spatial position of an elemental mixture region is denoted by x. Since different mixture constituents may have different motions, each constituent α which is currently at x originated from possibly distinct reference locations Xα. The motion of each constituent is thus described by its own function

| (A.16) |

A.1 Balance of mass

The content of each constituent may be given by the apparent density ρα, which represents the mass of constituent α in the elemental mixture volume. The equation of balance of mass for each constituent is given by

| (A.17) |

where vα = ∂χα/∂t is the constituent’s velocity, and ρ̂α is the mass density supply to constituent α from chemical reactions. The material derivative following constituent α is defined as

| (A.18) |

for any function f. The balance of mass for the entire mixture is given by

| (A.19) |

where

| (A.20) |

and requires that

| (A.21) |

implying that any net mass added to some of the constituents must exactly match the mass lost by the others. ρ represents the mixture density, and v is the mixture velocity.

Changes in ρα may occur as a result of changes in the mixture volume resulting from loading or as a result of chemical reactions that alter the mass of constituent α in the elemental mixture volume. It is possible to isolate the effect of growth by formulating the apparent density and mass supply of constituent α relative to the mixture volume in the reference configuration for that constituent (Bowen 1969; Guillou and Ogden 2006; Ateshian 2007),

| (A.22) |

where Jα = det Fα and Fα = ∂x/∂Xα. Substituting this relation into (Eq. A.17) produces

| (A.23) |

Thus, the quantity will only change as a result of chemical reactions, allowing an explicit distinction between the effects of growth and loading on the apparent density. This equation is very important in the theory of growth, as addressed in our prior studies (Ateshian 2007; Ateshian et al. 2009).

A.2 Balance of linear momentum

The equation of balance of linear momentum for each constituent is given by

| (A.24) |

where aα = Dαvα/Dt is the acceleration, Tα is the apparent Cauchy stress, bα is the external body force on constituent α per unit mass, and p̂α is the momentum supply to constituent α from interactions with all other constituents. The balance of momentum for the mixture is given by

| (A.25) |

where a = Dv/Dt and

| (A.26) |

and the following constraint must be satisfied,

| (A.27) |

In this relation,

| (A.28) |

is known as the diffusion velocity of constituent α relative to the barycentric mixture velocity. In biological tissues, the term ραuα ⊗ uα is typically negligible compared to Tα, so that the mixture stress is very nearly equivalent to its inner part,

| (A.29) |

In most problems, inertia terms given by ραaα in (Eq. A.24) and ρa in (Eq. A.25) are also negligible compared to other terms in those equations; therefore, differences between mixture theory and Biot’s theory of consolidation (Biot 1962), which appear in the inertia terms, are inconsequential in most biological applications.

A.3 Constitutive restrictions

In biological tissues, it is common to model solid and fluid constituents as intrinsically incompressible and to enforce electroneutrality at every point in the continuum. Intrinsic incompressibility implies that the true density of a constituent is invariant; the apparent and true density are related via

| (A.30) |

where φα if the volume fraction of that constituent. In a saturated mixture, the volume fractions satisfy

| (A.31) |

The electroneutrality condition is given by

| (A.32) |

where zα is the charge number and Mα is the molecular weight (always invariant) of constituent α. Constitutive restrictions may be imposed on mixtures by the second law of thermodynamics. The incompressibility and electroneutrality constraints may be introduced into the Clausius-Duhem inequality for mixtures using Lagrange multipliers.

As shown in previous studies, the multiplier for the incompressibility constraint represents a pressure p (Bowen 1980), while that for electroneutrality is Fcψ (Huyghe and Janssen 1997), where ψ is the electric potential in the mixture and Fc is Faraday’s constant. In such mixtures, the Clausius-Duhem inequality for mixtures becomes

| (A.33) |

where ψα and ηα are, respectively, the specific Helmholtz free energy and entropy for constituent α, Lα = ∇vα is the velocity gradient, qα is the heat flux vector for constituent α, and θ is the absolute temperature.

To proceed from this point, it is necessary to posit a set of state variables for ψα, ηα, Tα, p̂α, qα and ρ̂α. While we may appeal to the principle of equipresence and provide a long list of state variables, it is more expedient to adopt the following minimum set needed for our purposes,

| (A.34) |

where σ denotes solid constituents, ι denotes fluid constituents, and β refers to all of the constituents. In this choice of state variables, we are including deformation and growth of the solid matrix via the respective inclusion of Fσ and , since changes as a result of growth, (Eq. A.23). Solid matrix remodeling is ignored here; it is also assumed that these functions do not depend on the history of these state variables but only on their current value.

Using these state variables, the chain rule of differentiation on Dαψα/Dt yields

| (A.35) |

Though ψα appears as a convenient variable in the formulation of the Clausius-Duhem inequality, (Eq. A.33), constitutive relations are generally formulated in terms of the free energy density for the entire mixture. The free energy density for constituent α is given by Ψα = ραψα and that for the mixture is ΨI = ∑α Ψα. Then it can be shown that

| (A.36) |

Substituting these relations into (Eq. A.33) and grouping like terms yields

| (A.37) |

where we used the identities

| (A.38) |

and

| (A.39) |

Following standard arguments, the entropy inequality of (Eq. A.37) is satisfied for arbitrary processes if and only if

| (A.40) |

and

| (A.41) |

where

| (A.42) |

represent the chemical, mechano-chemical, and mechano-electrochemical potential of constituent α, respectively. In these expressions, is the dissipative part of the stress (such as viscous stresses), and is the dissipative part of the momentum supply (such as frictional interactions with other constituents). The reduced entropy inequality in (Eq. A.41) spells out the terms that may dissipate free energy in a thermodynamic process. Making use of (Eqs. A.30)–(A.33), the inner part of the mixture stress becomes

| (A.43) |

It should also be noted that the set of state variables for ΨI is now reduced based on (Eq. A.40), such that

| (A.44) |

Substituting the general expression for p̂α from (Eq. A.40) into the constraint of (Eq. A.27) produces a constraint on the choice of constitutive relations for ,

| (A.45) |

Of particular interest is the fact that for fluid constituents, the equation of balance of linear momentum, (Eq. A.24), when combined with the expressions for Tι and p̂ι in (Eq. A.40), now becomes

| (A.46) |

and it becomes apparent that the gradient in the mechano-electrochemical potential is an important driving force in the momentum balance of fluids. While a similar substitution may be performed for the solid constituents, the resulting expression does not simplify as nicely as for fluids. Nevertheless, for a mixture of unconstrained solids, that equation would be needed to describe the momentum response of each solid constituent. Since we are not interested in this more general case at this time, we proceed with the next step of constraining the solids to move together.

A.4 Constrained mixture of solids

We are now ready to consider a mixture where all the solid constituents are constrained to move together, (Eq. 5), even though they may have distinct reference configurations Xσ. The constraint may be simply expressed as vσ = vs where vs represents the common velocity of all solid constituents. For the purpose of incorporating this constraint into the entropy inequality, it may be rewritten as Lσ = Ls and introduced into (Eq. A.33) using a tensorial lagrange multiplier Λσ, thus adding the term

| (A.47) |

to that expression. In this case, all of the constitutive relations of (Eq. A.40) remain the same except for the solid stress, which now becomes

| (A.48) |

where

| (A.49) |

to satisfy the entropy inequality unconditionally for arbitrary changes in Ls; the resulting reduced entropy inequality keeps the same form as (Eq. A.41). Using these relations, the mixture stress also reduces to the same form as (Eq. A.43). Note that Λσ remains an indeterminate quantity in a mixture of constrained solid constituents. Therefore, the equation of balance of momentum for each solid constituent is no longer useful; the balance of momentum for the mixture, (Eq. A.25), should be used instead, to solve for the deformation of the constrained mixture of solids.

The expression for TI in (Eq. A.43) may be simplified further if the mixture free energy density was expressed relative to the mixture volume in some reference configuration (Biot 1972; Bowen 1980). Since all the solid constituents are constrained to move together, let us define the reference configuration Xs for the mixture such that it coincides with one of the reference configurations Xσ and then recognize that the various constrained solid constituents satisfy (Eq. 6). We would like to define a Helmholtz free energy per unit volume of the mixture in the reference configuration Xs,

| (A.50) |

where Js = det Fs. Equation 6 establishes a fixed relation between the reference configurations Xs and Xσ for the solid constituents; we also need to define a similar relation between the configuration Xs and the fluid constituents. Thus, let

| (A.51) |

represent the mass of fluid constituent ι in the current configuration, per unit volume of the mixture in the reference configuration Xs; and perform a change of state variables such that

| (A.52) |

By evaluating the total differential of (Eq. A.50) and using (Eqs. A.44), (A.51) and (A.52), it can be shown that

| (A.53) |

Substituting these relations into (Eq. A.43) yields the final desired result for the mixture stress,

| (A.54) |

Contributor Information

Gerard A. Ateshian, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, ateshian@columbia.edu

Tim Ricken, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

References

- Ateshian GA. On the theory of reactive mixtures for modeling biological growth. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2007;6(6):423–445. doi: 10.1007/s10237-006-0070-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Costa KD, Azeloglu EU, Morrison BI, Hung CT. Continuum modeling of biological tissue growth by cell division, and alteration of intracellular osmolytes and extracellular fixed charge density. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(10):101. doi: 10.1115/1.3192138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot M. Mechanics of deformation and acoustic propagation in porous media. J Appl Phys. 1962;33(4):1482–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Biot MA. Theory of finite deformations of porous solids. Indiana U Math J. 1972;21(7):597–620. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RM. Thermochemistry of reacting materials. J Chem Phys. 1968;49(4):1625–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RM. The thermochemistry of a reacting mixture of elastic materials with diffusion. Arch Ration Mech An. 1969;34(2):97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RM. Theory of mixtures. In: Eringen AE, editor. Continuum physics. vol 3. New York: Academic Press; 1976. pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RM. Incompressible porous media models by use of the theory of mixtures. Int J Eng Sci. 1980;18(9):1129–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Cowin SC, Hegedus DH. Bone remodeling-1. Theory of adaptive elasticity. J Elasticity. 1976;6(3):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald SE, Moore JEJ, Rachev A, Kane TP, Meister JJ. Experimental investigation of the distribution of residual strains in the artery wall. J Biomech Eng. 1997;119(4):438–444. doi: 10.1115/1.2798291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou A, Ogden RW. Growth in soft biological tissue and residual stress development. In: Holzapfel GA, Ogden RW, editors. Mechanics of biological tissue. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MH, Mow VC. The nonlinear characteristics of soft gels and hydrated connective tissues in ultrafiltration. J Biomech. 1990;23(11):1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JD, Rajagopal KR. A constrained mixture model for growth and remodeling of soft tissues. Math Mod Meth Appl S. 2002;12(3):407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Huyghe JM, Janssen JD. Quadriphasic mechanics of swelling incompressible porous media. Int J Eng Sci. 1997;35(8):793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Klisch S, Van Dyke T, Hoger A. A theory of volumetric growth for compressible elastic biological materials. Math Mech Solids (USA) 2001;6(6):551–575. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez EK, Hoger A, McCulloch AD. Stress-dependent finite growth in soft elastic tissues. J Biomech. 1994;27(4):455–467. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalak R, Dasgupta G, Moss M, Otten E, Dullumeijer P, Vilmann H. Analytical description of growth. J Theor Biol. 1982;94(3):555–577. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber LA, Humphrey JD. Stress-modulated growth, residual stress, and vascular heterogeneity. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123(6):528–535. doi: 10.1115/1.1412451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truesdell C, Toupin R. The classical field theories. In: Flugge S, editor. Handbuch der Physik. vol III/1. Berlin: Springer; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Volokh KY, Lev Y. Growth, anisotropy, and residual stresses in arteries. Mech Chem Biosyst. 2005;2(1):27–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossoughi J, Hedjazi Z, Borris FS. Adv Bioeng. ASME; 1993. Intimal residual stress and strain in large arteries; pp. 434–437. [Google Scholar]

- Wan W, Hansen L, Gleason RL., Jr A 3-d constrained mixture model for mechanically mediated vascular growth and remodeling. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10237-009-0184-z. doi:10.1007/s10237-009-0184-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]