Abstract

Airway smooth muscle cells are the main effector cells involved in airway narrowing and have been used to study the signaling pathways involved in asthma-induced airway constriction. Our previous studies demonstrated that ethanol administration to mice attenuated methacholine-stimulated increases in airway responsiveness. Because ethanol administration attenuates airway responsiveness in mice, we hypothesized that ethanol directly blunts the ability of cultured airway smooth muscle cells to shorten. To test this hypothesis, we measured changes in the size of cultured rat airway smooth muscle (RASM) cells exposed to ethanol (100 mM) after treatment with methacholine. Ethanol markedly attenuated methacholine-stimulated cell shortening (methacholine-stimulated length change = 8.3 ± 1.2% for ethanol versus 43.9 ± 1.5% for control; P < 0.001). Ethanol-induced inhibition of methacholine-stimulated cell shortening was reversible 24 hours after removal of alcohol. To determine if ethanol acts through a cGMP-dependent pathway, incubation with ethanol for as little as 15 minutes produced a doubling of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity. Furthermore, treatment with the PKG antagonist analog Rp-8Br-cGMPS (10 μM) inhibited ethanol-induced kinase activation when compared with control-treated cells. In contrast to the effect of ethanol on PKG, ethanol pretreatment did not activate a cAMP-dependent protein kinase. These data demonstrate that brief ethanol exposure reversibly prevents methacholine-stimulated RASM cell contraction. In addition, it appears that this effect is the result of activation of the cGMP/PKG kinase pathway. These findings implicate a direct effect of ethanol on airway smooth muscle cells as the basis for in vivo ethanol effects.

Keywords: alcohol, airway smooth muscle, methacholine, contraction, PKG

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

There is limited knowledge about the effect that alcohol has on contraction of airway smooth muscle cells. These data from this study provide a mechanistic basis for the bronchodilator properties of alcohol observed in humans and in animal models.

Inflammation and acute bronchoconstriction are characteristics of asthma and other inflammatory airway diseases. The main effector cell involved in the acute narrowing of the airway lumen is the airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell (1, 2). ASM cells have been used to study a myriad of human health–related questions, including changes in airway stiffness (3), airway receptor expression (4–7), the source of inflammatory mediators (8, 9), and the role of calcium in ASM contraction (10–14). These observations would otherwise be difficult to discern using in vivo models. In addition, Tao and others have demonstrated that cultured ASM cells can be used to determine contractile effects (15–17). The use of cultured ASM cells thus provides an appropriate model to study the nature and mechanism of ethanol's effect on airway contraction.

It has been well established that compounds such as methacholine and serotonin stimulate ASM contraction through the activation of muscarinic (M2 and M3) and serotonergic receptors. These are G protein–coupled receptors that propagate contraction by ultimately changing intracellular calcium levels. In contrast to receptor-mediated contraction, the cyclic nucleotides cAMP and cGMP are important mediators for relaxing ASM (18) through the activation of the cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA and PKG) pathways, respectively. Increased activation of these kinases, due to increases in cAMP and cGMP, plays a role in ASM relaxation (19–22).

ASM cells therefore have an important role in the pathophysiology of asthma, but evidence for a link between airway hyperresponsiveness and altered ASM contractility is uncertain (23, 24). We recently demonstrated that ethanol administration, via drinking water or intraperitoneal injection, attenuates methacholine-induced airway responsiveness in mice (25), which we speculate is due to direct effects on ASM cell reactivity. Alcohol is a known bronchodilator and has been used for centuries to treat airway ailments (26). Although many studies explore the effects of ethanol in organ systems such as the brain, kidney, and heart, few studies have elucidated how ethanol mediates bronchodilatory effects. Because our laboratory has previously shown an ethanol-mediated bronchodilatory effect in mice that consume ethanol, the purpose of this study was to determine by what mechanism this effect is occurring. This led us to hypothesize that ethanol directly inhibits methacholine-stimulated contraction of isolated ASM cells.

We tested this hypothesis in the present study by assessing rat ASM contractility in the presence and absence of ethanol through the use of an in vitro cell contractility assay. In addition to determining the effects of ethanol on contraction, we also investigated the mechanism by which ethanol alters contractility. To do so, we explored the effects of inhibition of guanylyl cyclase and defined the activation and inhibition of PKA and PKG in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rats

Male, 6- to 8-week-old Sprague Dawley rats from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) were kept in community cages with 12-hour periods of light and dark and maintained on standard rodent chow with access to water ad libitum. All animal care and experimentation was approved by and conducted in accordance with the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Chemicals and Reagents

Ethyl alcohol dehydrated (200 proof) was obtained from AAPER Alcohol and Chemical Co. (Louisville, KY). Cell culture media (DMEM:F12), heat-inactivated FBS, Pen/strep, and trypsin were purchased from Gibco/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). [γ-32P]ATP, fungizone (amphotericin B), FITC-conjugated monoclonal α-smooth muscle anti-actin, and acetyl-β-methylcholine chloride (methacholine) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Anti-smooth muscle myosin IgG was purchased from Biomedical Technologies, Inc. (Stoughton, MA). Secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) was obtained from Alexis Biochemicals (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Rp-8-Bromoguanosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate sodium salt (Rp-8Br-cGMPS) was purchased from Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Phosphocellulose P-81 paper was obtained from Whatman (Clifton, NJ). Heptapeptide substrate for PKA (LRRASLG) was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA), and Econosafe scintillation cocktail was acquired from Research Products International (Mt. Prospect, IL).

Rat Airway Smooth Muscle Cell Preparation

Rat airway smooth muscle (RASM) cells were isolated and cultured based on modifications of previous methods of An and colleagues and Zhai and colleagues (3, 27). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, and the tracheas were aseptically removed and cleared of connective tissue. The epithelia were removed from the luminal surface by gentle rubbing with a cotton-tipped applicator. ASM strips were dissected from the surrounding parenchyma underlying the connective tissue. The ASM strips were washed three times with DMEM containing 50 U/ml of penicillin, 20 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml of amphotericin B. The muscle was finely chopped and digested in DMEM containing 0.1% type I collagenase (1 mg/ml) for 3 hours at 37°C under 5% CO2. Enzyme digests were then centrifuged at 500 × g, and the pellet was resuspended and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 2 mM l-glutamine, pen-strep, and amphotericin B (1 μg/ml) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in 95% air at 37°C. Fresh medium was added, and cells were subcultured until confluency (usually by 2 wk). The identification of smooth muscle cells was confirmed by the presence of positive staining for α-smooth muscle actin and myosin, yielding 99% pure smooth muscle cells. When confluent, the cells were passaged with the use of 0.025% trypsin in 0.01% EDTA. Third- to fifth-passaged cells were plated in 12-well polystyrene plates or 60-mm polystyrene dishes in the above FBS-supplemented medium for experimentation.

Immunofluorescent Staining for α-Actin and Smooth Muscle Myosin

Cultured ASM cells were elongated and spindle shaped, grew with the typical hill-and-valley appearance under phase-contrast microscopy, and showed positive staining for α-actin and smooth muscle myosin (Figure 1), as previously described (28, 29). Briefly, primary ASM cells were passaged after reaching confluence with 0.025% trypsin in 0.01% EDTA into a 6-well plate containing glass coverslips. The coverslip was removed once the cells reached 50% confluence. The cells were then fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS(pH 7.4) for 7 minutes. FITC-conjugated anti-smooth muscle α-actin antibody (1:250 dilution in PBS) was applied after the cells were washed (three times with PBS for 5–10 min per wash). The cover glass was then incubated at 37°C for 2 hours and washed with PBS, and the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain antibody (1:300 dilution in PBS containing 3% BSA) at room temperature. The cover glass was washed with PBS, and the cells were further incubated with rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature. After the secondary antibody incubation, the cover glass was rinsed first in PBS and then in distilled water, mounted on a slide, and visualized using a confocal microscope (model LSM510; Carl Zeiss, Göettingen, Germany) using an argon/krypton laser (488 nm/594 nm/647 nm).

Figure 1.

Identification of rat airway smooth muscle (RASM) cells. Immunofluorescent staining of subcultured (fourth passage) RASM cells. Low magnification of unstained RASM cells with typical hill and valley appearance. (A) Light field view. (B) α-Actin. (C) Smooth muscle myosin. (D) Merged α-actin and myosin. Original magnification in panels B–D: ×40. Bar = 20 μm.

Contractility Assay

Cells were seeded (∼ 15,000 per well) and grown in 12-well cell culture plates. The well being tested was washed twice, 800 μl warm Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) added, and the plate was transferred to the heated stage (30°C) of an Olympus IMT-2 inverted phase contrast microscope for analysis. Images were recorded using the Sisson-Ammons Video Analysis system (30). An initial recording (time = 0 s) was made to obtain the size of quiescent cells. To measure contractile responses to specific agonists, 200 μl of HBSS or the agonist methacholine (100 μM) was added to the dish at time = 30 seconds, and the solution was gently mixed with the pipette. Images were recorded at 30-second intervals for 20 minutes. Contractility was assessed as previously described (16, 17). Briefly, the images were digitized, and the surface area and length of individual cells were analyzed (Image J, NIH Image). Only cells with a distinct longitudinal axis and clearly visible cell-substrate boundaries were selected for analysis. Surface area was obtained by tracing the outer boundary of the cell, and length was measured by drawing a line through the cell along its longest visible axis. The extent of contraction was calculated as the ratio of the change in surface area or length to the initial value. Only cells of passage 5 or less were used in the experiments.

Ethanol Pretreatment

Various concentrations of ethanol (1, 10, 50, and 100 mM) were used to pretreat the cells for dose–response experiments. In all other ethanol experiments, 100 mM ethanol in media stock was prepared fresh for each day of experiments, and 3 ml per well was added for 30 minutes. After pretreatment, the well being tested was washed twice with warm HBSS and aspirated, and 800 μl HBSS was added. The plate was then transferred to the microscope stage and evaluated as previously described.

Treatment with Antagonists

The prepared cells were pretreated with antagonist drugs for guanylyl cyclase (GC) and PKG. GC was blocked by adding 1 μM ODQ to the well of interest for 1 hour. Wells undergoing cyclase inhibition were transferred directly to the microscope after inhibition for contractility studies. Cells exposed to antagonist drugs and ethanol were first exposed to the antagonist for 1 hour; then 100 mM ethanol was added for an additional 30 minutes. The addition of 10 μM Rp-8Br-cGMPS and incubation for various times achieved PKG activity inhibition. Media was removed, and 250 μl of cell lysis buffer (35 mM Tris-HCl, 0.4 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, PMSF, leupeptin, aprotinin, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) was added. Cells were placed in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until assayed.

Reversibility Experiments

Cells were seeded and grown in 12-well cell culture plates. Ethanol/media (100 mM) was added for 30 minutes to the well being tested. The well was then washed twice, and 800 μl HBSS was added. The plate was transferred to the microscope for analysis as described in the contractility assay section. After 20 minutes, the plate was removed and washed twice. Fresh media (3 ml) was added, and the plate was returned to the incubator. After 24 hours, the cells were observed under the microscope to ensure reattachment to the plate. After the well was washed with 1 ml of HBSS and aspirated, 800 μl of HBSS was added, and the plate was transferred to the microscope for analysis, as previously described.

Cyclic Nucleotide-Dependent Kinase Activity Assay

ASM cells were cultured as previously described above. Cells were grown in 60-mm plates and treated with media, ethanol, or drug. After treatment, the culture media was removed, 250 μl of cell lysis buffer (35 mM Tris-HCl, 0.4 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.01 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.1% Triton X-100 [pH 7.4]) was added, and dishes of cells were then immediately placed in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until assayed. At the time of assay, the dishes of cells were thawed on ice, scraped with a cell scraper, and transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. Each sample was then sonicated for 6 to 10 seconds, put on ice for 15 minutes, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to collect the supernatant, which was assayed for kinase activity. To determine PKA activity in cultured rat ASM cells, smooth muscle cell protein was assayed in the presence or absence of 10 μM cAMP by a modification of the methods previously described (31) using a reaction mix consisting of 130 μM PKA heptapeptide substrate (LRRASLG) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 100 μM IBMX, 20 mM magnesium-acetate, and 200 μM [γ-32P]ATP. PKG activity was assayed similarly to PKA, with the substitution of the peptide RKRSRAE for the heptapeptide substrate, the addition of 10 μM cGMP, and the presence of protein kinase inhibitor peptide (32, 33). ASM protein (20 μl) was added to 50 μl of the reaction mix described above and incubated for 15 minutes at 30°C. Spotting the assay mix (60 μl) onto P-81 phosphocellulose papers halted the reaction. Papers were then washed five times for 5 minutes in 75 mM phosphoric acid and washed once in ethanol. Dried papers were counted in nonaqueous scintillation fluid, and kinase activity was expressed as picomoles of phosphate incorporated per minute per milligram of protein. Total protein was determined by the Bradford protein assay. All samples were assayed in duplicate or triplicate in at least three separate experiments. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA.

Statistics

All experimental data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism 4.0a (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA), and the average changes in length (or area) between different groups were analyzed by the Student's t test or ANOVA, where applicable, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. These tests were used to determine the level of significance between all treatment groups. A probability level of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of RASM Cells

We confirmed using confocal microscopy and immunofluorescence that the cultured airway cells were smooth muscle cells. Under the light microscope, cultured cells displayed the classic smooth muscle hill and valley morphology (Figure 1A). The cells stained positive for α-actin (Figure 1B) and anti-smooth muscle myosin (Figure 1C) using immunofluorescence. Figure 1D demonstrates that the fibers are colocalized by merging the actin and myosin images. No other cell types were detected as contaminating cells in the smooth muscle cell cultures.

Ethanol Blocks Methacholine-Induced RASM Cell Shortening

Once the cultured cells were established to be ASM cells, methacholine was added to determine RASM contractility. Treatment of non-ethanol cells with 100 μM methacholine caused marked shortening (43.9 ± 1.5% length reduction; P < 0.001 compared with HBSS treated-control). Cells contracted (rounded up) by 20 minutes after methacholine addition. In contrast, cells pretreated with 100 mM ethanol demonstrated significantly attenuated methacholine-stimulated shortening compared with non-ethanol treated cells (8.3 ± 1.2% for ethanol versus 43.9 ± 1.5% for non-ethanol treated; Figure 2B). Ethanol exposure comparably attenuated changes in RASM cell area (as opposed to length) when compared with non-ethanol exposed cells (15.3 ± 1.3% for ethanol versus 51.4 ± 1.2% for control; Figure 2C). Cells exposed to HBSS, the vehicle for methacholine, did not contract (data not shown). Because there were equivalently significant changes in length and area, the data throughout the remainder of the experiments are reported as changes in length.

Figure 2.

Methacholine exposure induces contraction in cultured RASM cells. (A) Cells in panel 1 depict cells at 0 minutes. Panel 2 shows the same cells 20 minutes after addition of 100 μM methacholine. Panel 3 (0 min) and panel 4 (20 min after addition of 100 μM methacholine) depict cells that were pretreated with 100 mM ethanol for 30 minutes. Note the increase in the number of small round cells that have contracted in panel 2A-2 compared with ethanol pretreated cells exposed to methacholine (panel 2A-4). (B) Graphical representation demonstrating that ethanol exposure significantly (***P < 0.001) attenuates changes in cell length after 100 μM methacholine exposure. (C) Graphical representation demonstrating that ethanol exposure significantly (***P < 0.001) attenuates changes in cell area after 100 μM methacholine exposure. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and represent at least 200 cells from at least eight separate experiments performed on multiple days.

Ethanol Concentration-Dependent Effects on Methacholine-Stimulated Attenuation in RASM Cells

Having established that ethanol dampens methacholine-stimulated cell shortening in RASM cells, dose–response experiments were undertaken to determine the optimal concentration for ethanol contractility attenuation. Cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of ethanol (1, 10, 50, and 100 mM) for 30 minutes. No significant changes in methacholine-induced cell shortening were observed after pretreatment with 1 mM or 10 mM ethanol (Figure 3). However, after treatment with 50 mM ethanol, there was a significant (P < 0.05) attenuation in methacholine-induced cell shortening. The greatest attenuation of contraction occurred after pretreatment with 100 mM ethanol. The 100 mM concentration was significantly different (P < 0.001) from both the untreated and 50 mM ethanol groups (9.6 ± 3.9% versus 43.9 ± 1.5% and 9.6 ± 3.9% versus 32.2 ± 4.0%, respectively). These data represent at least 75 different cells from at least four separate experiments performed on multiple days using cells derived from different rats.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of alcohol in RASM contraction. The vertical axis represents the percentage decrease in RASM cell length after stimulation with methacholine (100 μM). Cells were pretreated with 1, 10, 50, and 100 mM ethanol before methacholine stimulation. All bars represent at least 75 cells from at least four separate experiments performed on multiple days. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus no ethanol. **P < 0.001 versus no ethanol. #P < 0.001 versus 50 mM ethanol.

Ethanol Inhibition of Methacholine-Induced Contraction Is Reversible and Noncytotoxic

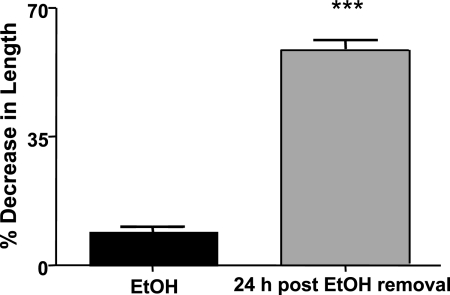

To establish that the ethanol effect of inhibiting methacholine-stimulated contraction was not the result of dehydration or fixation, alcohol was removed, and fresh media containing no alcohol was added to cells for 24 hours, followed by methacholine (100 μM) stimulation. When re-exposed to methacholine (100 μM), the cells vigorously contracted (Figure 4), indicating functional contractile viability. Ethanol pretreatment had a “priming” effect on the RASM cells because they contracted significantly (58.4 ± 2.9% versus 43.9 ± 1.5%; P < 0.001) more than ethanol naive cells treated with methacholine alone (data not shown). Cells reattached to the plates after re-exposure to methacholine (100 μM), further demonstrating that the 100 mM ethanol dose is nontoxic and that the ethanol effect is reversible.

Figure 4.

Ethanol inhibition of methacholine-induced contraction is reversible. Ethanol (100 mM) significantly attenuates the methacholine (100 μM) induced contraction (black bar), which resolved 24 hours after removal of ethanol (gray bar). Data are expressed as means ± SEM, and all bars represent at least 150 cells from at least three separate experiments performed on multiple days.

Ethanol Activates PKG

Because alcohol can stimulate airway nitric oxide (NO) production and NO is an effective bronchodilator, we performed experiments to determine if ethanol exerts its methacholine-blocking effect through a NO/PKG-dependent pathway in RASM cells. Ethanol (100 mM) was added to RASM cells and incubated for various time intervals followed by measurement of PKG activity. Figure 5A demonstrates that PKG activity was significantly (P < 0.001) increased in as little as 15 minutes and remained activated for up to 1 hour and returned to baseline by 24 hours. These data demonstrate that ethanol activates the PKG pathway. To further determine if alcohol activates the PKG signaling pathway in RASM cells, the cell-permeable, phosphodiesterase-resistant antagonist of PKG (Rp-8Br-cGMPS) was added to the cells in the presence or absence of ethanol. PKG activity was not increased after adding Rp-8Br-cGMPS and was significantly attenuated (P < 0.001) compared with the ethanol-alone elicited response and was unchanged compared with baseline media-treated cells (Figure 5B). The maximum PKG activity for these cells was achieved with the addition 8Br-cGMP, a known activator of PKG, for 15 minutes. Having demonstrated that ethanol can activate PKG activity in RASM cells and that inhibiting PKG activation can block this effect, we examined the role of upstream GC. Pretreatment of RASM cells with ODQ, a specific inhibitor of GC, inhibited ethanol's ability to block methacholine-stimulated contraction (Figure 5C). These inhibitor data strongly support a role of the cGMP/PKG pathway involvement in the ethanol-mediated inhibition of RASM cell contraction.

Figure 5.

(A) Ethanol activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG). Cells treated with 100 mM ethanol demonstrate a doubling of PKG activity in as little as 15 minutes, with return to baseline by 24 hours (*P < 0.001). Cells treated with the PKG-positive control 8Br-cGMP demonstrate maximum PKG activation. Data represent pooled data from at least three separate experiments run on separate days. (B) Treatment with the PKG inhibitor Rp-8Br-cGMPS (10 μM) blocks the ethanol-induced PKG activation (*P < 0.001 versus control media). Data represent pooled data from at least three separate experiments run on separate days. (C) Cells treated with the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) (1 μM) for 1 hour and then exposed to methacholine (100 μM) demonstrated no change from cells treated with methacholine (100 μM) alone (***P < 0.001 versus all other groups). Cells treated with ODQ, a guanylyl cyclase inhibitor, and then exposed to 100 mM ethanol for 30 minutes also demonstrated no attenuation in methacholine-induced contraction. ODQ bars represent at least 100 cells from at least six separate experiments performed on multiple days. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Ethanol Does not Activate PKA in RASM Cells

Because ethanol is known to potently activate PKG and PKA in airway epithelial cells (32), and PKA activation is known to promote bronchodilatation, we next explored the role PKA might play in mediating ethanol's effect on blocking RASM cell contraction. We exposed RASM cells to 100 mM ethanol for 15 minutes, 1 hour, or 24 hours to activate PKA. No differences were found in PKA activity between ethanol- and media-treated RASM cells (Figure 6). The positive assay control (8Br-cAMP) did show significant activation of PKA at the 15-minute time point indicating good assay reactivity.

Figure 6.

Ethanol does not activate cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). Cells treated with 100 mM ethanol exhibit no change in PKA activity compared with media-treated control cells. A positive assay control of cells stimulated with 10 μM 8Br-cAMP significantly activated PKA compared with media control (*P < 0.05). Data represent pooled data from at least three separate experiments run on separate days. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that ethanol exposure blocks ASM cell contraction in vitro. After as little as 30 minutes of exposure, ethanol significantly inhibits methacholine-stimulated changes in ASM cell length and area. This is not entirely unexpected because basic science and clinical studies suggest that alcohol can act as an effective bronchodilator (26). Our findings complement our published in vivo observations that alcohol blocks methacholine-stimulated bronchoconstriction in mice (25). Those experiments demonstrated that as long as ethanol remains in the drinking water, an attenuated/blocked methacholine response is observed, suggesting that the alcohol has substantively modified a signaling pathway or changed how the airway cells react to the methacholine challenge, although the mechanism was not determined.

Because culturing ASM cells can lead to changes in cell phenotype, the ASM preparations are extensively screened for the presence of actin, myosin, calponin, cell morphology, and PKG activity. These tests allow certainty that the cells being used in experiments are not other cell types of cells, such as fibroblasts or myofibroblasts. Only cells from passage 5 or less are used for experiments becauase PKG activity and the overall contractile reactivity of the cells are greatly diminished in higher-passaged cells and likely do represent a change in cell phenotype. Although contraction is affected by cell–substrate adhesion, this was not an obstacle in this study. Experiments using ASM grown on collagen-coated plates and also grown on a homologous cell substrate did not have any significant differences in contraction from ASM grown directly on plastic culture plates. After ethanol treatments the cells rounded, but they did not detach from the culture plate, so we did not observe ethanol to have any overt effects on cell adhesion. Because no single preparation can be used alone to study the regulation and function of ASM, the cultured ASM provides a convenient model system for studying the regulation of a wide range of airway responses at the cellular level. Although tracheal rings can be used to measure contraction in intact ASM, there are many factors that may influence contraction, such as connective tissues, epithelial cells, nitric oxide release, and release of other contractile mediators (e.g., serotonin or adenosine) from other cell types in the rings. Using the cultured ASM cells enabled us to eliminate these non-ASM cell factors and focus on direct effects of ethanol on the ASM muscle cell.

The regulation of ASM has been extensively studied (26, 28, 34), and findings suggest many possible mechanisms for the direct effect of ethanol attenuating the ASM cell contraction that we observed. The best-characterized signaling pathways implicated in airway relaxation are linked to increasing levels of the cyclic nucleotides cAMP and cGMP, with downstream activation of PKA and PKG, respectively. Because ethanol is known to activate PKA and PKG in airway epithelium, ethanol could modify key elements in these kinase-driven relaxation pathways in the ASM cell (Figure 7) (32, 35). We explored the mechanism(s) through which ethanol blocks methacholine-stimulated contraction by sequentially inhibiting key components of these nucleotide-dependent pathways. The ethanol smooth muscle relaxation effect appears to depend on guanylyl cyclase because inhibition of GC completely blocked the ethanol effect on muscle cell contraction (Figure 5C). The downstream kinases were also selectively triggered by ethanol, with 4-fold activation of PKG but no activation of PKA (Figure 6). These findings strongly implicate selective activation of PKG by ethanol in ASM cells (Figure 7), which is in sharp contrast to the dual kinase activation pathway by ethanol described in ciliated airway epithelial cells (32).

Figure 7.

Proposed ethanol-induced airway smooth muscle contraction attenuation pathway.

Other possible mechanisms for the ethanol-induced attenuation of ASM contraction may involve ethanol-induced alterations in membrane potential or calcium sensitivity. In permeabilized canine ASM strips, Hanazaki and colleagues found that ethanol promotes concentration-dependent ASM relaxation, via isometric force analysis in an isolated tissue bath, with an increased sensitivity to calcium that was independent of regulatory myosin light chain phosphorylation. This study concluded that there is a direct effect of ethanol on calcium-regulated smooth muscle tone, and this finding is consistent with literature demonstrating that alcohol acts as a bronchodilator (11). Based on the findings of Hanazaki, calcium may play a role in the observed ethanol-induced ASM relaxation observed in our study. Although the current study focuses on the effects of ethanol on PKA and PKG, ethanol may have effects on upstream targets like nitric oxide synthases or downstream targets such as mitogen-activated protein kinases. Ethanol could also be modifying actin-myosin interactions. Although these possibilities are out of the scope of this study, they could all be possible targets for the relaxation effects of ethanol in the ASM cells. Recently, small interfering RNA (siRNA) has been used to obtain more information about calcium activity in ASM cells (36, 37). Some of these studies have demonstrated that ORAI1 protein can be knocked down by siRNA, resulting in reduced thapsigargin- or cyclopiazonic acid–induced calcium influx in human ASM (36). It has also been demonstrated that siRNA against CD38 blunts TNF-α–induced increases in store operated calcium entry in human ASM, thereby altering airway responsiveness (37). These mechanisms may play an important role in our observed ethanol relaxation response but are beyond the scope of this study. Further studies are warranted to determine the role that calcium and changes in membrane potential play in the role of ethanol's modulation of altered methacholine-induced smooth muscle contraction.

Another important finding of these experiments is that the alcohol effect is reversible, which excludes overt cell toxicity, and, in an interesting twist, ethanol pretreatment appears to “sensitize” RASM cells because they have an enhanced contraction to methacholine 24 hours after the ethanol is removed (Figure 4). Held and Uhlig have discussed that smooth muscle cells and other resident cells can be primed to induce hypersensitivity to nonspecific stimuli like methacholine (38). This suggests that chronic exposure to ethanol might generate an enhanced attenuation of the relaxation response compared with naive exposure.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that ethanol blocks methacholine-induced contraction in cultured ASM cells, suggesting a direct effect of alcohol on airway contraction. This effect is reversible over time and is likely due to activation of guanylyl cylcase and PKG. These findings represent a novel approach of using alcohol to explore ASM contractility and provide a likely mechanism for the observed effects of alcohol in airway responsiveness in animal (25) and human studies (26).

The data presented in these experiments establish that alcohol can directly relax ASM cells. These data also demonstrate that the observed in vivo airway hyperresponsiveness effects do not necessarily have to be the result of ethanol-induced depression of the central nervous system. Future studies exploring upstream and downstream activation of the proposed pathway (Figure 7) will provide further insight into the relaxation inducing effects of alcohol on ASM cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Lisa Chudomelka for her help with the preparation of this manuscript and Chelsea Navarette for experimental assistance. They also thank Janice A. Taylor and James R. Talaska of the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for providing assistance with confocal microscopy and the Nebraska Research Initiative and the Eppley Cancer Center for their support of the Core Facility.

Supported by a Ruth K. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Grant 1F32AA017024 (P.J.O.) and National Institutes of Health grants 5R37AA008769 (J.H.S.) and 1R01AA017993 (T.A.W.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0252OC on November 20, 2009

Author Disclosure: P.J.O., J.H.S., and T.A.W. received a sponsored grant from DHHS/NIH/NIAAA for more than $100,001 each.

References

- 1.Fredberg JJ. Bronchospasm and its biophysical basis in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 2004;5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King GG, Pare PD, Seow CY. The mechanics of exaggerated airway narrowing in asthma: the role of smooth muscle. Respir Physiol 1999;118:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An SS, Laudadio RE, Lai J, Rogers RA, Fredberg JJ. Stiffness changes in cultured airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2002;283:C792–C801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morishima H, Kajiwara K, Akiyama K, Yanagihara Y. Ligation of toll-like receptor 3 differentially regulates m2 and m3 muscarinic receptor expression and function in human airway smooth muscle cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2008;145:163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pertel T, Zhu D, Panettieri RA, Yamaguchi N, Emala CW, Hirshman CA. Expression and muscarinic receptor coupling of lyn kinase in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L492–L500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenfeldt HM, Amrani Y, Watterson KR, Murthy KS, Panettieri RA Jr, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates contraction of human airway smooth muscle cells. FASEB J 2003;17:1789–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shan X, Hu A, Veler H, Fatma S, Grunstein JS, Chuang S, Grunstein MM. Regulation of toll-like receptor 4-induced proasthmatic changes in airway smooth muscle function by opposing actions of erk1/2 and p38 mapk signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L324–L333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallsworth MP, Soh CP, Twort CH, Lee TH, Hirst SJ. Cultured human airway smooth muscle cells stimulated by interleukin-1beta enhance eosinophil survival. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1998;19:910–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holgate S. Mediator and cytokine mechanisms in asthma. Thorax 1993;48:103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gosens R, Stelmack GL, Dueck G, Mutawe MM, Hinton M, McNeill KD, Paulson A, Dakshinamurti S, Gerthoffer WT, Thliveris JA, et al. Caveolae facilitate muscarinic receptor-mediated intracellular ca2+ mobilization and contraction in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L1406–L1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanazaki M, Jones KA, Perkins WJ, Warner DO. The effects of ethanol on ca(2+) sensitivity in airway smooth muscle. Anesth Analg 2001;92:767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moynihan B, Tolloczko B, Michoud MC, Tamaoka M, Ferraro P, Martin JG. Map kinases mediate interleukin-13 effects on calcium signaling in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L171–L177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez JF, Sanderson MJ. The frequency of calcium oscillations induced by 5-ht, ach, and kcl determine the contraction of smooth muscle cells of intrapulmonary bronchioles. J Gen Physiol 2005;125:535–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolloczko B, Jia YL, Martin JG. Serotonin-evoked calcium transients in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1995;269:L234–L240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eum SY, Maghni K, Tolloczko B, Eidelman DH, Martin JG. Il-13 may mediate allergen-induced hyperresponsiveness independently of il-5 or eotaxin by effects on airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L576–L584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govindaraju V, Michoud MC, Ferraro P, Arkinson J, Safka K, Valderrama-Carvajal H, Martin JG. The effects of interleukin-8 on airway smooth muscle contraction in cystic fibrosis. Respir Res 2008;9:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao F, Chaudry S, Tolloczko B, Martin JG, Kelly SM. Modulation of smooth muscle phenotype in vitro by homologous cell substrate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003;284:C1531–C1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu BN, Lin RJ, Lo YC, Shen KP, Wang CC, Lin YT, Chen IJ. Kmup-1, a xanthine derivative, induces relaxation of guinea-pig isolated trachea: the role of the epithelium, cyclic nucleotides and k+ channels. Br J Pharmacol 2004;142:1105–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamad AM, Clayton A, Islam B, Knox AJ. Guanylyl cyclases, nitric oxide, natriuretic peptides, and airway smooth muscle function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;285:L973–L983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ijioma SC, Challiss RA, Boyle JP. Comparative effects of activation of soluble and particulate guanylyl cyclase on cyclic gmp elevation and relaxation of bovine tracheal smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 1995;115:723–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komalavilas P, Penn RB, Flynn CR, Thresher J, Lopes LB, Furnish EJ, Guo M, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Brophy CM. The small heat shock-related protein, hsp20, is a camp-dependent protein kinase substrate that is involved in airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L69–L78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln TM, Cornwell TL. Towards an understanding of the mechanism of action of cyclic amp and cyclic gmp in smooth muscle relaxation. Blood Vessels 1991;28:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma X, Cheng Z, Kong H, Wang Y, Unruh H, Stephens NL, Laviolette M. Changes in biophysical and biochemical properties of single bronchial smooth muscle cells from asthmatic subjects. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;283:L1181–L1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solway J, Fredberg JJ. Perhaps airway smooth muscle dysfunction contributes to asthmatic bronchial hyperresponsiveness after all. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997;17:144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldenburg PJ, Wyatt TA, Factor PH, Sisson JH. Alcohol feeding blocks methacholine-induced airway responsiveness in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;296:L109–L114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sisson JH. Alcohol and airways function in health and disease. Alcohol 2007;41:293–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhai W, Eynott PR, Oltmanns U, Leung SY, Chung KF. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways in il-1 beta-dependent rat airway smooth muscle proliferation. Br J Pharmacol 2004;143:1042–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall IP, Kotlikoff M. Use of cultured airway myocytes for study of airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 1995;268:L1–L11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng B, Ansari HR, Oldenburg PJ, Schnermann J, Mustafa SJ. Isolation and characterization of coronary endothelial and smooth muscle cells from a1 adenosine receptor-knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006;290:H1713–H1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sisson JH, Stoner JA, Ammons BA, Wyatt TA. All-digital image capture and whole-field analysis of ciliary beat frequency. J Microsc 2003;211:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang H, Colbran JL, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Direct evidence for cross-activation of cgmp-dependent protein kinase by camp in pig coronary arteries. J Biol Chem 1992;267:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyatt TA, Forget MA, Sisson JH. Ethanol stimulates ciliary beating by dual cyclic nucleotide kinase activation in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 2003;163:1157–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wyatt TA, Spurzem JR, May K, Sisson JH. Regulation of ciliary beat frequency by both pka and pkg in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 1998;275:L827–L835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myou S, Fujimura M, Nishi K, Watanabe K, Matsuda M, Ohka T, Matsuda T. Effect of ethanol on airway caliber and nonspecific bronchial responsiveness in patients with alcohol-induced asthma. Allergy 1996;51:52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sisson JH, Pavlik JA, Wyatt TA. Alcohol stimulates ciliary motility of isolated airway axonemes through a nitric oxide, cyclase, and cyclic nucleotide-dependent kinase mechanism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:610–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. Orai and store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:744–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sieck GC, White TA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Wylam ME, Prakash YS. Regulation of store-operated ca2+ entry by cd38 in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L378–L385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Held HD, Uhlig S. Mechanisms of endotoxin-induced airway and pulmonary vascular hyperreactivity in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]