Abstract

Oxidative stress is widely proposed as a pathogenic mechanism for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but the molecular pathway connecting oxidative damage to tissue destruction remains to be fully defined. We suggest that reactive oxygen species (ROS) oxidatively damage nucleic acids, and this effect requires multiple repair mechanisms, particularly base excision pathway components 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (OGG1), endonuclease III homologue 1 (NTH1), and single-strand–selective monofunctional uracil-DNA glycosylase 1 (SMUG1), as well as the nucleic acid-binding protein, Y-box binding protein 1 (YB1). This study was therefore designed to define the levels of nucleic-acid oxidation and expression of genes involved in the repair of COPD and in corresponding models of this disease. We found significant oxidation of nucleic acids localized to alveolar lung fibroblasts, increased levels of OGG1 mRNA expression, and decreased concentrations of NTH1, SMUG1, and YB1 mRNA in lung samples from subjects with very severe COPD compared with little or no COPD. Mice exposed to cigarette smoke exhibited a time-dependent accumulation of nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar fibroblasts, which was associated with an increase in OGG1 and YB1 mRNA concentrations. Similarly, human lung fibroblasts exposed to cigarette smoke extract exhibited ROS-dependent nucleic-acid oxidation. The short interfering RNA (siRNA)-dependent knockdown of OGG1 and YB1 expression increased nucleic-acid oxidation at the basal state and after exposure to cigarette smoke. Together, our results demonstrate ROS-dependent, cigarette smoke-induced nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar fibroblasts, which may play a role in the pathogenesis of emphysema.

Keywords: COPD, emphysema, nucleic-acid oxidation, DNA/RNA repair

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

Cigarette smoke induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent nucleic-acid oxidation and apoptosis in alveolar fibroblasts. The repair of nucleic-acid oxidation may play a critical role as an antioxidant defense in ROS-induced chronic lung diseases such as emphysema.

Pulmonary emphysema is a pathologic process of alveolar destruction, with airspace enlargement not associated with significant amounts of fibrosis. It is a major component of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1). Cigarette smoke (CS) constitutes the main risk factor for pulmonary emphysema, and accumulating evidence supports the contention that oxidative stress is a key element in the pathogenesis of emphysema (2–5). In the lung, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated exogenously from CS or air pollutants, or endogenously from activated inflammatory cells and normal cell metabolism. Reactive oxygen species also act as second messengers in signal transduction, and both inflammatory stimuli and hypoxia may generate ROS as second messengers in COPD. A large number of antioxidant defenses (e.g., catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase) regulate ROS concentrations, but an oxidant/antioxidant imbalance leads to excess oxidative stress in COPD (2), with nucleic acids as an important target for oxidation. Of the bases in both DNA and RNA, guanine is the most susceptible to oxidation, and has been the most commonly studied marker of nucleic-acid oxidation. Reactive oxygen species can oxidize guanine to produce 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) in DNA, and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (8OHG) in RNA (6). The ROS-mediated modifications in DNA can result in base alterations, single-strand and double-strand breaks, and DNA-protein cross-links (7), and also play a critical role in transcriptional regulation by targeting specific promoter sequences (8). The oxidation of DNA also occurs in normal signaling, where it may regulate gene expression (9). Mitochondrial DNA was shown to be more sensitive to oxidative stress than nuclear DNA, and may induce mitochondrial dysfunction if not repaired (10, 11). The oxidation of RNA and its biological consequences have been less well characterized, but recent findings indicate that the oxidation of RNA disregulates translation, and induces translation errors (12).

To counteract nucleic-acid oxidation, multiple repair pathways exist. Oxidative DNA modifications are mainly repaired via the DNA base excision repair pathway, initiated by the excision of damaged bases by specific DNA glycosylases such as 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (OGG1), endonuclease III homologue 1 (NTH1), and single-strand–selective monofunctional uracil-DNA glycosylase 1 (SMUG1) (13). Oxidative RNA repair is a relatively new field, but accumulating evidence suggests that the repair of RNA oxidation may occur or, at least, oxidized RNA may be selectively bound for processing or sequestration (14, 15). The Y-box binding protein 1 (YB1) is a nucleic acid-binding protein involved in both transcriptional and translational control, and is able to bind oxidized RNA, thus removing it from the pool of translational material (16). Both DNA and RNA oxidation were shown to be involved in various pathologic processes (e.g., neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases) (17, 18), but nucleic-acid oxidation has received little attention in the pathogenesis of emphysema. Furthermore, nucleic-acid oxidation repair pathways have never been specifically investigated in emphysema.

We recently showed that the prevalence of nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells correlates with the severity of human emphysema (19). Alveolar lung fibroblasts are the main cell type in the lung interstitium, and play a pivotal role in the repair, remodeling, and maintenance of alveolar structure (20). In vitro studies showed that CS and ROS inhibit the recruitment and proliferation of lung fibroblasts, and induce apoptosis (21, 22). However, nucleic-acid oxidation and its consequences have not yet been investigated in lung fibroblasts.

This study sought to investigate ROS-induced nucleic-acid oxidation and the expression of genes involved in repair mechanisms in vivo in human severe emphysema and in a mouse model of CS-induced emphysema, and in vitro in normal adult lung fibroblasts exposed to CS extract.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Lung Sampling

Lung samples were obtained from six patients with very severe emphysema (stage 4 COPD), and who were receiving lung transplants. Freshly explanted lungs were frozen inflated over liquid nitrogen, imaged by X-ray computed tomography (CT), and processed for sampling as previously described (19). Briefly, 13-mm-diameter lung cores were sampled from 2-cm-thick transverse slices. The mean x-ray attenuation, expressed in Hounsfield units (HUs), was determined for each core, using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), as previously described (19, 23). For each patient, two cores with marked airspace enlargement, according to X-ray attenuation as measured using a CT scan (less than −950 HUs), were selected and analyzed. As control samples, lung tissue was obtained from seven patients without COPD and six patients with moderate/severe COPD (stages 2–3) who had undergone surgical resection for lung cancer, avoiding areas affected by tumors. The diagnosis of COPD was established according to the consensus statement of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (24). This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Studies Committee of Washington University. Informed consent was obtained for each subject. The clinical and functional characteristics of patients are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY GROUPS

| Non-COPD | COPDStages 2–3 | COPDStage 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Age, yr | 66 ± 12 | 69 ± 6 | 57 ± 7 |

| Sex, M/F | 4/3 | 3/3 | 2/4 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 45 ± 34 | 50 ± 24 | 67 ± 28 |

| Smoking status, current/former | 2/5 | 2/4 | 0/6 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 105 ± 12 | 49 ± 18 | 17 ± 4 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 77 ± 6 | 46 ± 14 | 27 ± 5 |

| TLC, % predicted | 100 ± 20 | 110 ± 21 | 142 ± 32 |

| RV, % predicted | 104 ± 32 | 162 ± 59 | 302 ± 115 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity.

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Mice Exposed to Cigarette Smoke

Ten-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) were exposed to mainstream CS 6 days/week, 4 cigarettes/day, for up to 6 months, using a previously described protocol (25). Mice were killed at different time points (1 d, 3 d, 1 mo, and 6 mo), 24 hours after their last exposure to CS. As control animals, age-matched mice were exposed to filtered air. All procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University School of Medicine.

Cell Culture and Treatments

Normal adult human lung fibroblasts (16 Lu) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Fibroblasts were maintained in Dubelcco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and nonessential amino acids at 37°C and 5% CO2. Fibroblasts were plated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate, or at 1 × 105 cells per well on a 2-well glass chamber slide for subsequent experiments.

Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) was prepared as previously described (26). Briefly, the smoke from two cigarettes without filters was bubbled through 15 ml of medium, and the resulting suspension (100% CSE) was passed through a 0.45-μm filter, and diluted with complete medium to 20%. Fibroblasts were incubated with diluted CSE for 3 to 24 hours. For studies including antioxidants, fibroblasts were preincubated with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC, 1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or desferrioxamine (DFX, 500 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes and then coincubated with CSE, as previously reported (27, 28). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and repeated at least three times.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from human and mice lung tissue samples, using the Purelink RNA Minikit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA synthesized using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was mixed with Taq Universal Master Mix and TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA), according to manufacturer's recommendations. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the following Taqman probes: OGG1 (Hs00249899_m1), YB1 (Hs00898625_g1), SMUG1 (Hs00204820_m1), NTH1 (Hs00267385_m1), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Hs00266705_1) in human studies, and OGG1 (Mm00501781_m1), YB1 (Mm850878_g1), and β2-microglobulin (Mm00437764_m1) in mouse studies. Relative differences among samples between groups or treatment conditions were determined using the median value of the control group for a reference.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm paraffin-embedded lung sections of humans and mice, using the Vectastain immunostaining kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and the following primary antibodies: (1) anti-8OHG/8OHdG (1:200, 30 min; QED Bioscience, San Diego, CA), a marker of DNA/RNA oxidation, (2) anti-vimentin (1:1,000, 30 min; Sigma-Aldrich), a marker of lung fibroblasts, or (3) isotype-matched, nonimmune IgG. Counterstaining was performed using nuclear fast red (American Master Tech Scientific, Lodi, CA). The colocalization of nucleic-acid oxidation (8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells) and alveolar wall fibroblasts (vimentin-positive cells) was investigated in serial sections of both human COPD and CS-exposed mouse lung samples. Thequantification of 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining in alveolar wall cells was performed as previously described (19). Briefly, 10 randomly selected, nonoverlapping fields were captured. The total numbers of alveolar wall cells (at least 50 cells per field), 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells, and vimentin-positive cells were manually counted on serial sections while the researcher was blinded to the identity of samples. The percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells relative to the total number of alveolar wall cells and the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG and vimentin-positive cells were calculated.

The immunostaining of 8OHG/8OHdG was also assessed in 16 Lu fibroblasts that were exposed to CSE. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformadehyde/PBS-diethylpyrocarbonate (PFA/PBS-DEPC) for 10 minutes, and then used for immunohistochemistry with the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody, as described above.

In some experiments, lung tissue sections or 16 Lu fibroblasts were treated with RNase A (10 μg/L, DNase-free; Sigma-Aldrich) or DNase I (2 U/μl, RNase-free; Sigma-Aldrich) or both for 60 minutes at 37°C before incubation with the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody, as previously described (19, 29).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence studies were performed on frozen sections of lung samples obtained from mice exposed to filtered air or to CS for 6 months, and on 16 Lu fibroblasts grown on 2-well glass chamber slides and exposed to 20% CSE for 3 or 24 hours. Slides were washed with PBS and fixed with ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes at −20°C. Cells were probed with the mouse anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody (1:200), followed by TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:200) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting media with DAPI, allowing us to visualize nuclei (Vector Laboratories).

Flow Cytometry

The extent of nucleic-acid oxidation in 16 Lu fibroblasts after exposure to CSE was determined by flow cytometry. The 16 Lu fibroblasts were harvested at 3 or 24 hours after treatment with media alone or CSE, washed with PBS-DEPC, fixed with 4% PFA (10 min, 4°C), and permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS-DEPC/4% FBS (10 min, 4°C). Cells were then incubated with the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody (1:200, 30 min, 4°C). After washing in PBS-DEPC/4% FBS, cells were incubated with the FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies of relevant isotypes. As control samples, cells were incubated with primary antibody alone, isotype-matched control antibody, or secondary antibody alone. Fluorescent intensity was determined using a FACScalibur unit (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Events were collected with a suitable threshold to exclude cell debris. At least 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed. To avoid any potential effect of background levels, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was calculated by subtracting the background MFI (cells incubated with secondary antibody alone) to the MFI of cells incubated with the primary antibody anti-8OHG/8OHdG. The fold-change in MFI in CSE-exposed fibroblasts was expressed relative to untreated fibroblasts.

In some experiments, cells were treated with RNase A (10 μg/L, DNase free; Sigma-Aldrich), DNase I (2 U/μl, RNase-free; Sigma-Aldrich), or both before incubation with the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody. The DNase/RNase induced a dramatic decrease in CSE-induced 8OHG/8OHdG MFI, indicating the specificity of the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody for nucleic-acid oxidation (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

In Vitro Inhibition of OGG1 and YB1 by siRNA

Double-stranded siRNA duplexes targeting human OGG1 or YB1 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The 16 Lu fibroblasts were plated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate for 24 hours, and then transfected with 20 nM siRNA duplex, using INTERFERin siRNA transfection reagent (Polyplus-Transfection, Inc., San Marcos, CA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Two different siRNA duplexes per gene were used independently in each experiment. The efficiency of transfection was examined in each experiment according to real-time qRT-PCR, using gene-specific Taqman probes. Only those experiments in which at least 70% knockdown was achieved were used for analysis. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control sample. Cells were stimulated with 20% CSE, 48 hours after transfection.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, except where otherwise indicated. Differences between groups were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and differences between individual variables from two groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Nucleic-Acid Oxidation in Alveolar Lung Fibroblasts and the Expression of OGG1, NTH1, SMUG1, and YB1 in Humans with Severe Emphysema

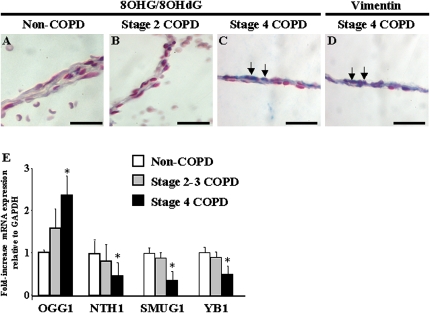

We recently demonstrated that alveolar wall cells exhibit high levels of nucleic-acid oxidation in patients with very severe COPD, and showed a correlation between the prevalence of nucleic-acid oxidation and the extent of emphysema (19). Because alveolar fibroblasts are critical for the structural integrity of the alveolar wall, we investigated whether alveolar lung fibroblasts exhibit nucleic-acid oxidation in human emphysema. We performed immunohistochemistry for 8OHG/8OHdG, a marker of nucleic-acid oxidation, and vimentin, a marker for fibroblasts. Compared with patients without COPD (Figure 1A) and patients with stage 2 COPD (Figure 1B), a marked increase occurred in 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining in alveolar wall cells in stage 4 COPD (Figure 1C). The immunostaining of serial sections demonstrated a prominent colocalization of 8OHG/8OHdG (Figure 1C) and vimentin staining (Figure 1D) in alveolar wall lung fibroblasts of patients with stage 4 COPD (Figures 1C and 1D), and 41% ± 6% of alveolar wall cells were positive for 8OHG-8OHdG and vimentin. Cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining did not reveal marked apoptosis in alveolar wall cells in COPD samples with less than 1% of positive cells (not shown).

Figure 1.

Nucleic-acid oxidation and repair in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Immunohistochemistry for 8OHG/8OHdG was performed in lung samples obtained from (A) patients without COPD, (B) patients with stage 2 COPD, and (C) patients with stage 4 COPD. (D) Immunohistochemistry for vimentin was performed on serial sections in lung samples of stage 4 COPD. Positive staining appears in blue. Arrows indicate the colocalization of 8OHG/8OHdG and vimentin immunostaining in alveolar wall cells. Bars = 50 μm. (E) The mRNA expression of OGG1, NTH1, SMUG1, and YB1 relative to GAPDH was investigated in whole-lung total RNA samples from seven patients without COPD, six patients with stage 2–3 COPD, and six patients with stage 4 COPD. Differences between groups were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and differences between two groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05, stage 4 COPD, compared with stages 2–3 and non-COPD.

To determine whether the increased nucleic-acid oxidation in very severe COPD was associated with changes in the mRNA expression of genes involved in the repair of nucleic-acid oxidation, we examined the expression of the DNA glycosylases OGG1, NTH1, and SMUG1 and the nucleic acid-binding protein YB1 in lung samples at various stages of COPD. Compared with lungs without COPD and with stage 2–3 COPD, the expression of OGG1 mRNA was significantly increased in stage 4 COPD (P < 0.05), whereas the expression of NTH1, SMUG1, and YB1 were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) (Figure 1E). Together, these results show that alveolar fibroblasts exhibit marked nucleic-acid oxidation in severe emphysema, and suggest the differential expression of genes involved in nucleic-acid oxidative repair in severe emphysema.

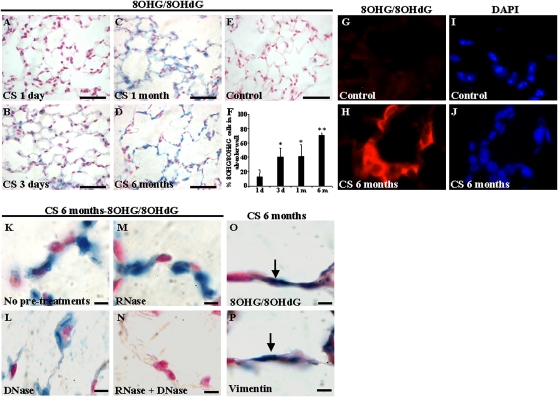

Nucleic-Acid Oxidation Occurs in Alveolar Fibroblasts in Cigarette Smoke–Induced Emphysema in Mice

To investigate the effects of chronic exposure to CS on nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells, we used a mouse model of CS-induced emphysema. The strain used in this study (C57BL/6) is susceptible to the development of CS-induced emphysema, and our group previously showed that C57BL/6 mice exposed to 6 months of CS exhibit significant airspace enlargement (25). The 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining detected in alveolar wall cells was low after 1 day of CS exposure (Figure 2A), but had significantly increased after 3 days (Figure 2B), 1 month (Figure 2C), and 6 months (Figure 2D) of CS exposure. By contrast, mice not exposed to CS for 6 months did not exhibit detectable nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells (Figure 2E). The quantification of the number of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells indicated an increase in nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells with extended chronic exposure to CS (Figure 2F). Immunofluorescence studies were performed in frozen lung sections of mice exposed to filtered air (Figures 2G and 2I) or to CS (Figures 2H and 2J). Compared with mice exposed to filtered air (control mice), lung sections from mice exposed to CS for 6 months exhibited marked 8OHG/8OHdG (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells in mice exposed to CS, with 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (blue) in C57BL/6 mice exposed to cigarette smoke (CS) for (A) 1 day, (B) 3 days, (C) 1 month, or (D) 6 months. (E) Control mice were exposed to filtered air for 6 months. Scale bars = 100 μm (A–E). (F) Percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar cells at different time points of CS exposure. Results are from at least four mice per group. Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, 3-day and 1-month CS exposure compared with 1 day of CS exposure. **P < 0.01, 6-month CS exposure compared with 1 day, 3 days, and 1 month of CS exposure. Immunofluorescence for 8OHG/8OHdG is depicted in lung samples from mice exposed to filtered air (G, I) or CS (H, J) for 6 months. (K–N) Comparison between slides not pretreated (K) or pretreated with DNase (L), RNase (M), or both (N) before 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining in mice exposed to CS for 6 months. Immunohistochemistry for 8OHG/8OHdG (O) and vimentin (P) is depicted in serial sections in lung samples from mice exposed to CS for 6 months. Arrows indicate colocalization of 8OHG/8OHdG and vimentin immunostaining in alveolar wall cells. Scale bars = 10 μm (K–P).

Because the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody used in this study detects both DNA and RNA oxidation, we performed RNase and DNase pretreatments before 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining to determine whether DNA, RNA, or both were oxidized in alveolar wall cells in mice exposed to CS for 6 months. Compared with slides without pretreatments (Figure 2K), pretreatments with DNase eliminated nuclear 8OHG/8OHdG staining but not the cytoplasmic signal (Figure 2L), whereas pretreatments with RNase eliminated cytoplasmic 8OHG/8OHdG staining but not the nuclear signal (Figure 2M). Combined pretreatment with both RNase and DNase eliminated all 8OHG/8OHdG staining, showing the selectivity of staining for nucleic acids (Figure 2N). Together, these results demonstrate that both nuclear DNA and cytoplasmic RNA oxidation are prominent features of alveolar wall cells in the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema.

Immunostaining in serial sections demonstrated the colocalization of 8OHG/8OHdG (Figure 2O) and vimentin (Figure 2P) staining in alveolar wall lung fibroblasts in mice exposed to CS for 6 months, and 47% ± 6% of alveolar wall cells were positive for 8OHG-8OHdG and vimentin.

mRNA Expression of OGG1 and YB1 in Cigarette Smoke–Induced Emphysema in Mice

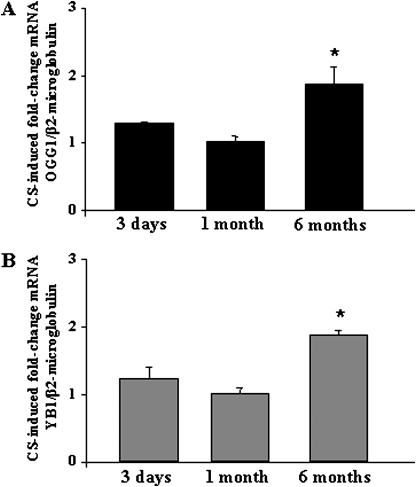

Because marked nucleic-acid oxidation occurred in alveolar fibroblasts during chronic CS exposure in mice, we examined the mRNA expression of the DNA glycosylase OGG1 and the nucleic acid-binding protein YB1 at various times of CS exposure. Compared with mice not exposed to CS, the mRNA expression of OGG1 (Figure 3A) and YB1 (Figure 3B) was significantly increased after 6 mo of CS exposure (P < 0.01), whereas 3 days and 1 month of CS exposure were not associated with significant changes in OGG1 and YB1 expression (Figures 3A and 3B). These results demonstrate that long-term chronic exposure to CS in mice induces an up-regulation of genes involved in nucleic-acid oxidation repair.

Figure 3.

The mRNA expression of OGG1 and YB1 in mice exposed to CS. The mRNA expression of (A) OGG1 and (B) YB1 were investigated in whole-lung total RNA samples from C57BL/6 mice exposed to CS for 3 days, 1 month, or 6 months, and compared with age-matched mice exposed to filtered air. Results are from at least four mice per group. Mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05, 6-mo CS exposure compared with 3 days and 1 month of CS exposure.

CSE Induces Nucleic-Acid Oxidation in Normal Adult Lung Fibroblasts

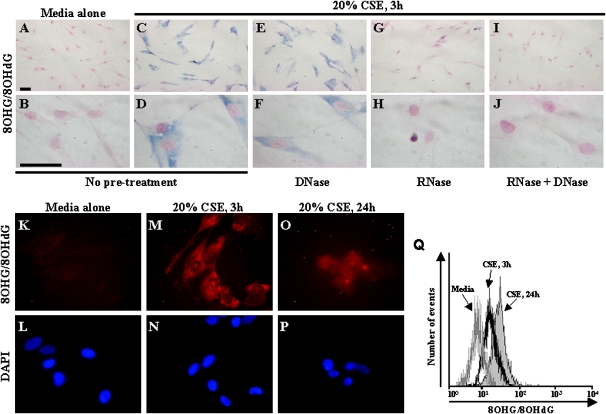

To determine whether CS directly induces nucleic-acid oxidation in fibroblasts, normal adult human lung fibroblasts (16 Lu) were exposed to CSE in vitro. Compared with fibroblasts exposed to media alone (Figures 4A and 4B), a marked increase in 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining was evident in fibroblasts exposed to 20% CSE for 3 hours (Figures 4C and 4D). The 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining was localized mainly in the cytoplasm, but also in the nucleus in some cells. To determine whether DNA, RNA, or both were oxidized, cells were pretreated with DNase, RNase, or both before 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining. The DNase did not dramatically decrease 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining, and marked staining remained in the cytoplasm (Figures 4E and 4F). The RNase dramatically decreased 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining in the cytoplasm, with only very low immunostaining remaining in some nuclei (Figures 4G and 4H). The combination of RNase and DNase eliminated all 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (Figures 4I and 4J). Together, these results indicate that a 3-hour exposure to CSE induces nucleic-acid oxidation in fibroblasts, and suggest that RNA oxidation may be prominent.

Figure 4.

Nucleic-acid oxidation in human lung fibroblasts exposed to CSE in vitro. Immunohistochemistry for 8OHG/8OHdG is depicted in fibroblasts exposed to (A, B) media alone or (C, D) 20% CSE for 3 hours. Effects are depicted of pretreatments with (E, F) DNase, (G, H) RNase, and (I, J) RNase/DNase combined on 8OHG/8OHdG staining in fibroblasts exposed to 20% CSE for 3 hours. Positive staining appears in blue. Scale bar = 50 μm. Immunofluorescence is depicted for (K, M, O) 8OHG/8OHdG in fibroblasts exposed to (K, L) media alone or (M, N) 20% CSE for 3 hours or (O, P) 24 hours. Flow cytometry for 8OHG/8OHdG (Q) is depicted in fibroblasts exposed to media alone (gray line), or 20% CSE for 3 hours (black line) or 24 h (solid gray). All experiments were performed in triplicate in at least three independent experiments.

Compared with fibroblasts exposed to media alone (Figures 4K and 4L), immunofluorescence analyses showed that 3 hours of exposure to 20% CSE (Figures 4M and 4N) was associated with the prominent cytoplasmic localization of 8OHG/8OHdG. By contrast, fibroblasts exposed to 20% CSE for 24 hours (Figures 4O and 4P) exhibited nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of 8OHG/8OHdG. The nuclei of fibroblasts exposed to CSE for 24 hours (Figure 4P) appeared much more condensed (a marker of apoptosis) than those of fibroblasts exposed to media alone (Figure 4L) or 20% CSE for 3 h (Figure 4N). Together, these results demonstrate that short-term exposure (3 h) to CSE induces mainly cytoplasmic nucleic-acid oxidation, whereas prolonged exposure (24 h) induces both nuclear and cytoplasmic nucleic-acid oxidation.

To quantify nucleic-acid oxidation in fibroblasts, flow cytometric analyses of 8OHG/8OHdG immunofluorescence were performed in fibroblasts exposed to CSE. The fluorescence intensity of 8OHG/8OHdG increased in fibroblasts exposed to CSE in a time-dependent manner, with higher levels of 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence detected after 24-hour exposure to 20% CSE (Figure 4Q).

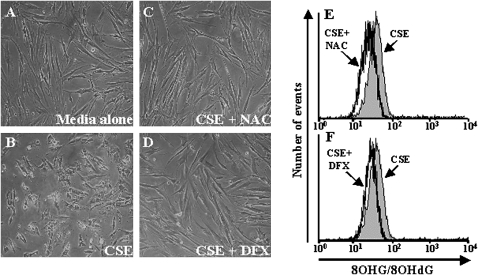

ROS in CSE Induce Nucleic-Acid Oxidation and Apoptosis in Fibroblasts

Cigarette smoke contains numerous oxidants, as well as a large number of chemicals with potential effects on fibroblasts. To determine the contributions of ROS in CSE-induced nucleic-acid oxidation, fibroblasts were exposed to CSE in the presence of antioxidants, NAC, a nonspecific antioxidant scavenger, or desferrioxamine (DFX), an iron chelator that reduces free iron available for the Fenton reaction, thus decreasing the production of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals. Compared with fibroblasts treated with medium alone (Figure 5A), an increase in cell-rounding was detected in fibroblasts exposed to 20% CSE for 24 hours (Figure 5B). The presence of NAC (Figure 5C) or DFX (Figure 5D) during CSE exposure dramatically decreased the amount of cell-rounding induced by exposure to CSE. Flow cytometric analyses demonstrated that both NAC and DFX treatment resulted in decreased CSE-induced 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence intensity (Figures 5E and 5F). Together, these results suggest that ROS in CSE play a critical role in the induction of nucleic-acid oxidation in fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

Effects of antioxidants on CSE-induced nucleic-acid oxidation and apoptosis in human fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were treated with (A) media alone or with (B) 20% CSE for 24 hours in the absence or (C) presence of NAC or (D) DFX. Flow cytometry for 8OHG/8OHdG (E, F) was performed on fibroblasts treated with 20% CSE for 24 hours alone (solid gray) or concurrent with antioxidants NAC (black line) (F, H) or DFX (black line) (G, I). All experiments were performed in three independent experiments in triplicate.

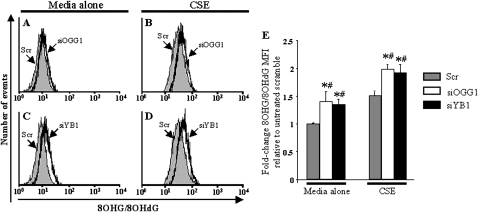

Effects of In Vitro Inhibition of OGG1 and YB1 on Nucleic-Acid Oxidation and Apoptosis in Fibroblasts

To investigate whether nucleic-acid oxidation repair pathways are involved in the regulation of nucleic-acid oxidation, we down-regulated OGG1 (the major DNA glycosylase involved in DNA repair) and YB1 (a nucleic acid-binding protein), using double-stranded siRNA duplexes. Flow cytometry analyses showed that fibroblasts transfected with a scrambled (Scr) siRNA duplex, used as negative control samples, and exposed to media alone, did not exhibit significant nucleic-acid oxidation or apoptosis, as indicated by low levels of 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence intensity (Figures 6A and 6C). By contrast, fibroblasts transfected with OGG1 (siOGG1) or YB1 (siYB1) siRNA duplexes and exposed to media alone exhibited a slight increase in 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence intensity (Figures 6B, 6D, and 6E). Transfection with siRNA itself did not alter the susceptibility of fibroblasts to 20% CSE, because the fold-increase in 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence intensity (Figures 6B, 6D, and 6E) in fibroblasts transfected with the Scr siRNA was similar to that of untransfected fibroblasts (Figure 4Q). Interestingly, the down-regulation of either OGG1 or YB1 with siRNA resulted in augmented levels of CSE-induced 8OHG/8OHdG fluorescence intensity (Figures 6B, 6D, and 6E). These results demonstrate that the nucleic-acid oxidation repair pathways mediated by OGG1 and YB1 are critical in counteracting nucleic-acid oxidation at both the basal state and after exposure to CS in lung fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Effects of down-regulation of OGG1 and YB1 on CSE-induced nucleic-acid oxidation in human fibroblasts. Flow cytometry for 8OHG/8OHdG (A–D) is depicted in fibroblasts transfected with siOGG1 (black line) (A, B), with siYB1 (black line) (C, D), or with a scrambled siRNA (Scr) as negative control sample (solid gray). Fibroblasts were exposed to (A, C) media alone or (B, D) 20% CSE for 24 hours. (E) Fold-change in 8OHG/8OHdG mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in fibroblasts transfected with Scr siRNA (gray bars), siOGG1 (open bars), or siYB1 (solid bars) was determined after exposure to media alone or to 20% CSE for 24 hours. All experiments were performed in three independent experiments in triplicate. Mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney U test. *P < 0.05, siOGG1 and siYB1 compared with Scr. #P < 0.05, media alone compared with CSE.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated the nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar lung fibroblasts of patients with severe emphysema, which was associated with changes in the expression of genes involved in the repair of oxidized nucleic acids. The mRNA expression of OGG1 was increased, and expression of NTH1, SMUG1, and YB1 was reduced, in stage 4 COPD compared with lungs at stage 2–3 COPD and without COPD. In the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema, we demonstrated a time-dependent accumulation of oxidized DNA and RNA in alveolar fibroblasts, associated with an increase in mRNA expression of OGG1 and YB1. In vitro studies of lung fibroblasts demonstrated that CSE induces ROS-dependent nucleic oxidation, and that the inhibition of either OGG1 or YB1 causes significant increases in nucleic-acid oxidation at both the basal state and after exposure to CSE.

This study focused on alveolar fibroblasts, which are essential for alveolar development (30), and which synthesize the elastin and collagen-rich network of fibers that form the architecture of the alveolus. Chronic inflammation from exposure to CS causes an induction of proteinases that target alveolar collagen and elastic fibers, compromising alveolar integrity and leading to emphysema (20, 31). Our view of the pathogenesis of COPD is becoming more complex as we learn more about the roles of oxidative injury, apoptosis, and other pathways. Our data indicate that not only is the extracellular matrix, as synthesized by alveolar fibroblasts, a target of pathologic processes leading to COPD, but these cells are also directly affected by nucleic-acid oxidation in addition to other injury pathways.

We previously showed that alveolar wall cells in human COPD exhibit mainly RNA oxidation (19), whereas this study reveals prominent DNA oxidation in alveolar wall cells in a mouse model of CS-induced emphysema. Our in vitro studies showed that human fibroblasts exposed to CSE for 24 hours exhibit mainly DNA oxidation, whereas 3 h of exposure to CSE induce mainly RNA oxidation. A direct link is difficult to establish between the increased ROS resulting from chronic CS exposure and alveolar enlargement in vivo. In humans, these processes lead to physiologic and morphologic changes over decades. In mice, months of chronic CS exposure result in mild to moderate alveolar enlargement. Carnevali and colleagues showed that CS induces apoptosis in lung fibroblasts (21), but additional studies are needed to understand the relative contributions and the relationships between RNA/DNA oxidation and apoptosis in lung fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of COPD.

The antioxidant response, driven in part by NF-E2–related factor 2 (26, 32), does not suffice to prevent oxidative modifications to proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids in mice exposed to CS and in human lungs with COPD (5, 19, 33). Our in vitro studies of fibroblasts show that nucleic-acid oxidation resulting from CSE is ROS-dependent (i.e., scavengers blunted the response). Next, we sought to determine whether a link exists between the expression of genes involved in nucleic-acid repair and the extent of nucleic-acid oxidation. In human emphysema and in the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema, we studied the mRNA expression of OGG1 as an index of DNA glycosylase activity, and YB1 as a potential marker for binding or processing oxidized RNA. The expression of OGG1 mRNA increased in the lungs in very severe human COPD and in the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema. OGG1 is a DNA glycosylase with bifunctional activity that plays a critical role in both nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA repair (34), and likely acts directly to control the accumulation of oxidized DNA. Although OGG1 null mice do not have a distinct phenotype and are only moderately more susceptible to cancer (35), OGG1-deficient fibroblasts exhibit an increased generation of ROS (36) and an enhanced sensitivity to DNA damage in response to oxidative stress (37). Our knockdown studies clearly show that nucleic-acid oxidation is increased at both the basal state and after exposure to CSE in human lung fibroblasts. These results functionally implicate OGG1 as important in both baseline and exogenous ROS-dependent nucleic-acid oxidation. By contrast, YB1 was repressed in very severe COPD, but was induced by chronic exposure to CS in mice. This finding is indicative of important differences and caveats in comparing human COPD with the mouse smoking model. Our very severe COPD samples were from patients who had ceased smoking for at least 1 year, and the non-COPD and stage 2–3 COPD patients had an associated diagnosis of lung cancer. Lung cancer was shown to be associated with a high expression of YB1 (38). In this study, areas affected by lung tumors were avoided, but we cannot rule out that mRNA expression may have been affected by lung tumors even in distant “normal” cells. Despite disparate expression patterns of YB1 in human COPD and the smoking mouse model, the knockdown of YB1 in human fibroblasts induced an increase of nucleic-acid oxidation at both the basal state and after exposure to CSE, suggesting a role for YB1 in regulating baseline and external ROS-dependent nucleic-acid oxidation. Because YB1 has many functions that potentially affect the repair of nucleic-acid modifications, it is not yet clear precisely how the suppression of YB1 leads to increased nucleic-acid oxidation. YB1 binds a wide variety of forms of nucleic acids, including single-stranded DNA and oxidized DNA and RNA (16). YB1 also regulates DNA repair by inducing some base excision repair enzymes (39), and plays a role in a large variety of cellular functions, such as chromatin remodeling, the transcriptional and translation regulation of many cellular growth-related and death-related genes, drug resistance, and stress responses to extracellular signals (40). Mice null for the YB1 gene exhibit severe growth retardation after Embryonic Day 13.5 and progressive mortality related to neurologic lesions, severe hemorrhage, and respiratory failure (41). In concordance with our findings, mouse embryonic fibroblasts isolated from YB1 null mice exhibit reduced abilities to respond to oxidative stress, and exhibit enhanced oxidative-induced senescence (41). Together, these results suggest that YB1 may play a critical role in oxidative stress-induced responses. However, we must point out that the mRNA changes in OGG1 and YB1 are modest in both human COPD and in the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema. Because oxidative stress may affect both the translation and the activity of these proteins, whether these modest changes in mRNA expression are associated with changes in protein expression and repair activity in COPD remains to be determined. Interestingly, human lung fibroblasts exposed in vitro to CSE were shown to exhibit DNA strand breaks that were reversible when CSE was removed (42), suggesting that active repair occurred after exposure to CSE. Our studies showed an accumulation of nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells in human COPD and in the mouse model of CS-induced emphysema, suggesting a potential failure to effect repairs in the context of in vivo chronic exposure to oxidative stress. However, additional studies are needed to investigate DNA/RNA repair activity and its potential failure in the context of COPD.

The oxidation of DNA is involved in various pathophysiologic processes in cancer, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases (17). Emphysema was shown to be an independent predictor of lung cancer (43). Our results, indicating the accumulation of nucleic-acid oxidation in emphysema, may be viewed as a potential link between tissue destruction and lung cancer, but additional studies are required to address this specific hypothesis. The oxidation of RNA has received much less attention, but recent findings indicated that RNA oxidation is directly involved in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases (18). In concordance with our results, RNA oxidation was shown to be an early event preceding and inducing cell death in neuronal cultures exposed to hydrogen peroxide (44). We recently showed that alveolar wall cells in severe emphysema exhibit marked nucleic-acid oxidation, and that RNA oxidation was a prominent feature in alveolar wall cells (19). In this study, we investigated the time course of long-term (up to 6 mo) CS-induced DNA and RNA oxidation in alveolar wall cells. Previous studies of mice exposed to CS mainly focused on DNA oxidation and short-term CS exposure, and demonstrated elevated DNA oxidation mainly in bronchiolar cells (45, 46). Our study used an antibody detecting both DNA and RNA oxidation, and found a time-dependent accumulation of DNA and RNA oxidation in alveolar wall cells in mice exposed to CS.

The focus on alveolar fibroblasts constitutes a limitation of our study. Our studies of both human COPD and mice exposed to CS clearly show that alveolar cell types other than fibroblasts are exposed to oxidative stress during the development of COPD. Alveolar type II cells exhibit DNA oxidation in mice after CS exposure (46). Rangasamy and colleagues showed that alveolar type II cells exhibit higher levels of apoptosis in a mouse model of CS-induced emphysema (47). When exposed to CSE, A549 cells (an alveolar type II cell-derived cell line) exhibit ROS-dependent oxidative stress and apoptosis (27). Interestingly, A549 cells exposed in vitro to hydrogen peroxide exhibit DNA and RNA oxidation, with predominant RNA oxidation (48). Pulmonary vessels are also a major component of alveolar interstitium, and endothelial dysfunction may play a critical role in COPD. The ROS generated in hypoxic pulmonary endothelial cells cause oxidative base modifications that modify the transcriptional activation of key genes such as VEGF (49). Recently, endothelial cells were shown to exhibit high levels of apoptosis in a mouse model of CS-induced emphysema (47).

Another limitation of our study involves its focus on selected candidate members of two nucleic acid-oxidative repair pathways, the DNA glycosylase OGG1 and the nucleic acid–binding protein YB1. The repair of oxidative DNA modifications is far more complex and involves many DNA glycosylases other than OGG1, as well as numerous endonucleases, ligases, and polymerases (13). We found that the expression of OGG1 mRNA was significantly induced in stage 4 COPD, whereas the expression of NTH1 and SMUG1, two other DNA glycosylases involved in the base-excision repair pathway, were downregulated, suggesting a differential regulation of DNA glycosylases other than OGG1. Nucleotide-excision repair and mismatch repair are also involved in oxidative DNA repair. Human alkB homologues may play a role in RNA as well as DNA repair, and YB1 is able to bind oxidized RNA (50, 51). Very little is known about the coordination, regulation, and roles of these genes in ROS-induced lung disease. To establish functional roles, mice with altered or null expression of nucleic acid-oxidative repair genes, including OGG1 and YB1, may prove powerful in the mouse model of chronic CS exposure.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated ROS-dependent, CS-induced nucleic-acid oxidation in alveolar fibroblasts. We think these results open a new and largely overlooked field in COPD, but additional studies are needed to understand the role of nucleic-acid oxidation and repair pathways in ROS-induced chronic lung diseases such as emphysema.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P50HL084922. G.D. received grants for postdoctoral training from Region Champagne-Ardenne, the University of Rheims, CHU of Reims, Association d'Aide aux Insuffisants Respiratoires de Champagne-Ardenne, College des Enseignants de Pneumologie, and AstraZeneca.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0221OC on December 11, 2009

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J Clin Invest 2008;118:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J 2006;28:219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Petrache I. State of the art. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacNee W. Oxidants and COPD. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005;4:627–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JL, Churg A. Current concepts in mechanisms of emphysema. Toxicol Pathol 2007;35:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans MD, Cooke MS. Factors contributing to the outcome of oxidative damage to nucleic acids. Bioessays 2004;26:533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J 2003;17:1195–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pastukh V, Ruchko M, Gorodnya O, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN. Sequence-specific oxidative base modifications in hypoxia-inducible genes. Free Radic Biol Med 2007;43:1616–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillespie MN, Wilson GL. Bending and breaking the code: dynamic changes in promoter integrity may underlie a new mechanism regulating gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;292:L1–L3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Houten B, Woshner V, Santos JH. Role of mitochondrial DNA in toxic responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitiello PF, Wu YC, Staversky RJ, O'Reilly MA. P21(cip1) protects against oxidative stress by suppressing ER-dependent activation of mitochondrial death pathways. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;46:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka M, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Oxidized messenger RNA induces translation errors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zharkov DO. Base excision DNA repair. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008;65:1544–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shyu AB, Wilkinson MF, van Hoof A. Messenger RNA regulation: to translate or to degrade. EMBO J 2008;27:471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Wu J, Deleo CJ. RNA damage and surveillance under oxidative stress. IUBMB Life 2006;58:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayakawa H, Uchiumi T, Fukuda T, Ashizuka M, Kohno K, Kuwano M, Sekiguchi M. Binding capacity of human YB-1 protein for RNA containing 8-oxoguanine. Biochemistry 2002;41:12739–12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: induction, repair and significance. Mutat Res 2004;567:1–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunomura A, Moreira PI, Takeda A, Smith MA, Perry G. Oxidative RNA damage and neurodegeneration. Curr Med Chem 2007;14:2968–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deslee G, Woods JC, Moore C, Conradi SH, Gierada DS, Atkinson JJ, Battaile JT, Liu L, Patterson GA, Adair-Kirk TL, et al. Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in severe emphysema. Chest 2009;135:965–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Fijalkowka I, Biswal S, Petrache I. Role of lung maintenance program in the heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:673–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carnevali S, Petruzzelli S, Longoni B, Vanacore R, Barale R, Cipollini M, Scatena F, Paggiaro P, Celi A, Giuntini C. Cigarette smoke extract induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;284:L955–L963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnevali S, Luppi F, D'Arca D, Caporali A, Ruggieri MP, Vettori MV, Caglieri A, Astancolle S, Panico F, Davalli P, et al. Clusterin decreases oxidative stress in lung fibroblasts exposed to cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woods JC, Choong CK, Yablonskiy DA, Bentley J, Wong J, Pierce JA, Cooper JD, Macklem PT, Conradi MS, Hogg JC. Hyperpolarized 3HE diffusion MRI and histology in pulmonary emphysema. Magn Reson Med 2006;56:1293–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hautamaki RD, Kobayashi DK, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Requirement for macrophage elastase for cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. Science 1997;277:2002–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adair-Kirk TL, Atkinson JJ, Griffin GL, Watson MA, Kelley DG, DeMello D, Senior RM, Betsuyaku T. Distal airways in mice exposed to cigarette smoke: NRF2-regulated genes are increased in Clara cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:400–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoshino Y, Mio T, Nagai S, Miki H, Ito I, Izumi T. Cytotoxic effects of cigarette smoke extract on an alveolar type II cell-derived cell line. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;281:L509–L516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer BM, Voynow JA. Neutrophil elastase induces MUC5AC gene expression in airway epithelium via a pathway involving reactive oxygen species. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nunomura A, Chiba S, Kosaka K, Takeda A, Castellani RJ, Smith MA, Perry G. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroreport 2002;13:2035–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bostrom H, Willetts K, Pekny M, Leveen P, Lindahl P, Hedstrand H, Pekna M, Hellstrom M, Gebre-Medhin S, Schalling M, et al. PDGF-A signaling is a critical event in lung alveolar myofibroblast development and alveogenesis. Cell 1996;85:863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Perkins DL, Kobayashi DK, Kelley DG, Marconcini LA, Mecham RP, Senior RM, Shapiro SD. Elastin fragments drive disease progression in a murine model of emphysema. J Clin Invest 2006;116:753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of NRF2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kode A. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airway diseases. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;533:222–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boiteux S, Radicella JP. The human OGG1 gene: structure, functions, and its implication in the process of carcinogenesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000;377:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Furuichi M, Xu P, Tsuzuki T, Sekiguchi M, Nakabeppu Y. OGG1 knockout-associated lung tumorigenesis and its suppression by MTH1 gene disruption. Cancer Res 2003;63:902–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bacsi A, Chodaczek G, Hazra TK, Konkel D, Boldogh I. Increased ROS generation in subsets of OGG1 knockout fibroblast cells. Mech Ageing Dev 2007;128:637–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu M, Che W, Zhang Z. Enhanced sensitivity to DNA damage induced by cooking oil fumes in human OGG1 deficient cells. Environ Mol Mutagen 2008;49:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gessner C, Woischwill C, Schumacher A, Liebers U, Kuhn H, Stiehl P, Jurchott K, Royer HD, Witt C, Wolff G. Nuclear YB-1 expression as a negative prognostic marker in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J 2004;23:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das S, Chattopadhyay R, Bhakat KK, Boldogh I, Kohno K, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Hazra TK. Stimulation of NEIL2-mediated oxidized base excision repair via YB-1 interaction during oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 2007;282:28474–28484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohno K, Izumi H, Uchiumi T, Ashizuka M, Kuwano M. The pleiotropic functions of the Y-box-binding protein, YB-1. Bioessays 2003;25:691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu ZH, Books JT, Ley TJ. YB-1 is important for late-stage embryonic development, optimal cellular stress responses, and the prevention of premature senescence. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:4625–4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim H, Liu X, Kobayashi T, Conner H, Kohyama T, Wen FQ, Fang Q, Abe S, Bitterman P, Rennard SI. Reversible cigarette smoke extract-induced DNA damage in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Balkan A, Schragin JG, Fuhrman CR, Fisher SN, Wilson J, Leader JK, Siegfried JM, Shapiro SD, et al. Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:738–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shan X, Chang Y, Lin CL. Messenger RNA oxidation is an early event preceding cell death and causes reduced protein expression. FASEB J 2007;21:2753–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Betsuyaku T, Hamamura I, Hata J, Takahashi H, Mitsuhashi H, Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM, Nishimura M. Bronchiolar chemokine expression is different after single versus repeated cigarette smoke exposure. Respir Res 2008;9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoshiba K, Koinuma M, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Immunohistochemical evaluation of oxidative stress in murine lungs after cigarette smoke exposure. Inhal Toxicol 2003;15:1029–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rangasamy T, Misra V, Zhen L, Tankersley CG, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in A/J mice is associated with pulmonary oxidative stress, apoptosis of lung cells, and global alterations in gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;296:L888–L900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hofer T, Badouard C, Bajak E, Ravanat JL, Mattsson A, Cotgreave IA. Hydrogen peroxide causes greater oxidation in cellular RNA than in DNA. Biol Chem 2005;386:333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruchko MV, Gorodnya OM, Pastukh VM, Swiger BM, Middleton NS, Wilson GL, Gillespie MN. Hypoxia-induced oxidative base modifications in the VEGF hypoxia-response element are associated with transcriptionally active nucleosomes. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;46:352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aas PA, Otterlei M, Falnes PO, Vagbo CB, Skorpen F, Akbari M, Sundheim O, Bjoras M, Slupphaug G, Seeberg E, et al. Human and bacterial oxidative demethylases repair alkylation damage in both RNA and DNA. Nature 2003;421:859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M. Human polynucleotide phosphorylase protein in response to oxidative stress. Biochemistry 2006;45:6749–6755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.