Abstract

Mutations in the tumor suppressor tuberin (TSC2) are a common factor in the development of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). LAM is a cystic lung disease that is characterized by the infiltration of smooth muscle–like cells into the pulmonary parenchyma. The mechanism by which the loss of tuberin promotes the development of LAM has yet to be elucidated, although several lines of evidence suggest it is due to the metastasis of tuberin-deficient cells. Here we show that tuberin-null cells become nonadherent and invasive. These nonadherent cells express cleaved forms of β-catenin. In reporter assays, the β-catenin products are transcriptionally active and promote MMP7 expression. Invasion by the tuberin-null cells is mediated by MMP7. Examination of LAM tissues shows the expression of cleaved β-catenin products and MMP7 consistent with a model that tuberin-deficient cells acquire invasive properties through a β-catenin–dependent mechanism, which may underlie the development of LAM.

Keywords: caspase 3, MMP7, LAM, tuberous sclerosis complex

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

Mechanisms underlying lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) remain poorly understood. Our findings provide new insights into the potential contribution of beta-catenin and its effectors, including MMP7, in the pathogenesis of LAM and other disorders affected by the TSC2 pathway.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a potentially fatal cystic lung disease that occurs almost exclusively in women. There are no proven medical therapies for the treatment of LAM, and the health of patients with LAM deteriorates over an average span of 10 years due to the progressive destruction of the lungs (1). LAM is predominantly caused by tuberin loss-of-function mutations, forming a genetic link with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (2–4). Recent analyses estimate that 30 to 40% of women with TSC may also be affected with LAM (5).

TSC is a multisystem disease that results in the growth of benign tumors in the brain, kidneys, heart, and skin. It commonly affects the central nervous system, resulting in any combination of disorders including seizures, mental retardation, and behavioral problems (6). One of the most common phenotypic factors for TSC is the development of renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs), which occur in approximately 70 to 80% of patients with TSC (7, 8). AMLs are characterized by the abnormal proliferation of dysplastic vessels and adipose and smooth muscle–like cells. Up to 60% of patients with sporadic LAM are diagnosed with AMLs (9). Genetic analyses have demonstrated that LAM cells and AML cells isolated from patients with LAM contain identical TSC2 mutations, suggesting that tuberin-deficient AML smooth muscle–like cells may have the potential to migrate and infiltrate the lung (3).

The benign metastasis hypothesis of LAM is further supported by two independent clinical observations. First, after lung transplantation, there have been several case reports in which LAM develops anew in the transplanted donor lung, with LAM cells expressing the same TSC2 mutation identified in the native lung (10–13). Second, LAM cells have recently been isolated from the circulatory system and other bodily fluids of patients with LAM, indicating that these migratory cells have the potential to invade a variety of host tissues (14). These lines of evidence strongly suggest that the development of LAM is due to the metastatic spread of tuberin-deficient cells from other sites of origin.

The mechanism of TSC-related metastasis is unknown. Here, we report that tuberin-null (Tsc2−/−) cells produce nonadherent, viable cells that are invasive. These cells maintain constitutive levels of caspase 3 activity, which promotes the cleavage of β-catenin. Examination of a TSC animal model and human LAM tissues demonstrates the presence of truncated β-catenin, corroborating the significance of cleaved β-catenin in the in vivo systems. These truncated forms of β-catenin are transcriptionally active and promote the expression of MMP7, a component of cell invasion. Nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells possess the ability to invade collagen matrices and epithelial feeder cell layers in a β-catenin– and MMP7-dependent fashion. We show for the first time that LAM lesions express MMP7, suggesting that the activity of truncated β-catenin is relevant to LAM physiology. These results provide evidence for a role of β-catenin in the invasive phenotype of Tsc2−/− cells, which may play an important role in the development of LAM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines

EEF-4 (Tsc2+/+), EEF-8 (Tsc2−/−), and EEF-4a (Tsc2−/−) are three independently derived fibroblast cell lines from Eker rat embryos (15). LEF2 and ERC18M are two independent Tsc2−/− renal epithelial tumor cell lines derived from Eker rats (16). The human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cell line stably expressing the TOPFLASH reporter was a kind gift of T. Biechele and R.T. Moon (University of Washington).

Animal and Human Tissues

Kidney tumors and adjacent normal kidney tissues were procured from Tsc2+/− Eker rats (17). Human lung and LAM tissues were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange. Experiments involving animal tissues were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and those involving human tissues were approved by Institutional Review Board, both at the University of Washington.

Cell Viability Assays

Collected cells were rinsed with PBS and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. A total of 100 μl of cell suspension was added to 500 μl of 0.4% trypan blue solution (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), diluted with 400 μl PBS, and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Viable and nonviable cells were counted by hemacytometer. Each assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments, presented as a percentage of viable cells.

Cell Cycle Analyses

Cells were analyzed by 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (18). Confluent Tsc2−/− cells (EEF-8, EEF-4a) were incubated with fresh media containing BrdU at a final concentration of 100 mM. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 72 hours after reaching confluence, and nonadherent cells in the media were collected and centrifuged. A total of 2.5 × 105 pelleted cells were then resuspended in Hoechst buffer (0.154 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris [pH 7.4], 0.1% NP40, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2% BSA, 1.2 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 dye [Calbiochem/EMD, Gibbstown, NJ]) for 30 minutes. Cells were counterstained with ethidium bromide and added to a final concentration of 6 μg/ml for 15 minutes. Chicken erythocyte nuclei (Riese Enterprises Inc. BioSure Division, Grass Valley, CA) were added to each sample to provide a quantitative numerical standard. The samples were analyzed on a Coulter-epics Elite flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA) with approximately 3 × 104 cells counted per sample. Proliferating cells were identified by BrdU quenching of Hoechst fluorescence compared with ethidium bromide fluorescence. DNA content and cell cycle analyses were performed using the software program MultiCycle (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA) at the University of Washington Flow Cytometry Facility.

Flow Cytometry Cell Sorting

Samples were analyzed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Annexin V Kit; AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) with minor modifications. In brief, nonadherent cells were rinsed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells in 195 μl of binding buffer. Samples were incubated for 10 minutes in the dark at room temperature with annexin V-FITC reagent. Cells were washed with binding buffer and resuspended in 190 μl of binding buffer with propidium iodide reagent added before cell sorting analysis. Optimal flow cytometer parameter settings were obtained with cells pretreated with 1 μM staurosporine (STS) (Calbiochem) or 10 mM NaN3 for 24 hours to enhance apoptotic and nonviable cell populations, respectively, as controls. Cells were sorted into three distinct populations using an Influx Flow Cytometer (Cytopeia/BD, Seattle, WA) at the University of Washington Flow Cytometry Facility.

TUNEL Assays

Apoptosis was detected in tissue sections by TUNEL assays using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). In brief, tissue sections were rehydrated according to standard protocols. Samples were microwaved in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes and then rinsed with PBS. Next, samples were incubated with TUNEL reaction mixture in a humidity chamber in the dark at 37°C for 60 minutes and then rinsed with PBS. Converter-peroxidase solution was added to each sample, and samples were incubated in the humidity chamber for 30 minutes and then rinsed with PBS. Samples were incubated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Roche) substrate for 10 minutes, rinsed with PBS, and counterstained with hematoxyin. Mounted samples were examined by light microscopy.

Coimmunoprecipitations

Cell lysates (200 μg) were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg of GSK3β or β-catenin antibodies. Addition of protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with incubation at 4°C for 4 hours followed. Samples were washed with 0.5% NP40 buffer (0.5% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaVO4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin) and analyzed by 7 and 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon, and immunoblotted for GSK3β and β-catenin proteins with a 1:1,000 dilution of primary antibody solution (GSK3β and β-catenin; BD Transduction; Franklin Lakes, NJ). All Westerns were probed with mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antisera (GE Healthcare/Amersham, Pittsburgh, PA) at a dilution of 1:2,000 with proteins detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Amersham).

Tissue Analyses

Eker rat and human lung tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer (1% NP40, 1% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate [pH 7.2], 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaVO4, 240 μg/ml AEBSF, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 0.4 μM microcystin) with protein content determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Eker rat (50 μg), normal lung (100 μg), and LAM tissues (100 μg) were analyzed by 7 and 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon, and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies at 1:1,000 dilution (β-actin and smooth muscle α-actin, Sigma; S6 ribosomal protein and phospho-S6 ribosomal protein, Cell Signaling; MMP7, Chemicon). Normal lung tissues were derived at autopsy from donors deceased from nonlung-related illnesses. LAM tissues were derived from explanted lungs of patients with LAM at the time of lung transplantation. Both sets of tissues were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA). All Westerns were probed with mouse or rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antisera (GE Healthcare/Amersham) as appropriate at a dilution of 1:2,000 with proteins detected by ECL.

In Vitro Caspase Assays

Caspase activity assays were performed as described elsewhere with slight modifications (19). Briefly, caspase 3 activity was measured using the substrate DEVD-AMC (BIOMOL). Caspase 6 and 8 activities were measured using the substrates, VEID-AMC and IETD-AMC, respectively (BIO MOL, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Cells were harvested and lysed in 0.5% NP40 buffer. Up to 50 μg of protein lysate was incubated at 37°C in a caspase assay buffer (200 mM NaCl, 40 mM PIPES [pH 7.2], 20 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA, 20% sucrose, 0.2% CHAPS, 40 μM substrate). Enzymatic assays and 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Sigma) standard curves were performed in duplicate using a fluorescent plate reader (Packard Instruments) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 460 nm, respectively. Fluorescence of the substrate blank was subtracted as background for each assay. Data analysis was performed using I-Smart software (Packard Instruments). Each activity assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of several independent experiments, presented as the pmol of substrate cleaved per mg of protein sample per minute of incubation time.

For the caspase 3 inhibitor assays, Tsc2−/− (8) cells before reaching confluence (60% confluent) were treated daily with DMSO (Sigma) or 25 μM ZVAD-FMK (Calbiochem) for 3 days. During this period, the cells attained confluence. Pooled cells (adherent and nonadherent) from each time point and treatment were harvested, lysed, and analyzed for in vitro caspase 3 activity as described above.

Construction of β-Catenin Mutants

The pCS3–β-catenin+MT plasmid was first digested with ClaI and StuI enzymes and then relegated to delete the C-terminal Myc tags (MT) generating an untagged Xenopus β-catenin construct (pCS3–β-catenin). Three sets of oligos were designed for use in QuikChange mutagenesis techniques (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Oligos to delete residues 1 through 115 (caspase 3 cleavage sequence TQFD115) were designed to incorporate a BamHI site followed by a START codon upstream of residue 115. Oligos to delete residues 765 through 781 (caspase 3 cleavage sequence DLMD764) were designed to incorporate a STOP codon followed by a SnaBI site beginning at residue 765. Oligos to delete residues 752 through 781 (caspase 3 cleavage sequence YPVD751) were designed to incorporate a STOP codon followed by a SnaBI site beginning at residue 752. Gene products were sequenced and then subcloned into the pCS3–β-catenin vector through the use of BamHI and SnaBI sites.

Mass Spectrometry Analyses

For identification of cleaved forms of β-catenin in the Tsc2−/− cells, N-Adh Tsc2−/− cell lysates (1 mg) were immunoprecipitated with β-catenin antibody. Immunoprecipitated products were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was fixed overnight in gel fixing solution (50% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) and washed in gel washing solution (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) before staining with Coomassie Blue R250 (Sigma) stain (0.1% Coomassie Blue, 20% methanol, 10% acetic acid) for 1 hour. The gel was destained with several washes of destain solution (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) until background was clear. The gel was equilibrated in storage solution (5% acetic acid) for 1 hour. Coomassie Blue–stained protein bands were excised and subjected to reduction, alkylation, and trypsin digestion procedures as recommended by the University of Washington Medicinal Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Center. Peptide samples were analyzed at the University of Washington Medicinal Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Center by nanoflow LC-MS/MS analysis (Micromass Quattro).

Transfections and Reporter Assays

For transient transfection of β-catenin mutants, HEK293 cells (ATCC) at 50% confluence were transfected with the previously described β-catenin mutant constructs (1.6 μg) using Lipofectamine PLUS transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, cells were harvested with PBS and lysed with 0.5% NP40 buffer. Protein content was determined by BCA assay. For immunoprecipitation, 200 μg of cell lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg of MMP7 antibody. Addition of protein A-Sepharose beads (Sigma) with incubation overnight at 4°C followed. Samples were washed with 0.5% NP40 buffer. Cell lysate and immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by 7 and 12.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon, and immunoblotted for β-catenin and MMP7 proteins with a 1:1,000 dilution of primary antibody solution. All Westerns were probed with mouse or rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antisera at a dilution of 1:2,000 with proteins detected by ECL.

For luciferase reporter assays, cDNA expression constructs (0.8 μg) for β-catWT (wild-type β-catenin), β-cat116–781, β-cat116–764, β-cat116–751, and dominant negative TCF4 were cotransfected with a renilla luciferase thymidine kinase reporter plasmid (pRLTK) (20 ng) to normalize for transfection efficiencies. 293T-TOPFLASH stable, HEK293, and Tsc2−/− (8) cells were used for TOPFLASH, cyclin D1, and MMP7 reporter assays, respectively. A total of 200 ng of the cyclin D1 reporter and 1 μg of the MMP7 reporter construct (−296 HMAT Pro), a kind gift from H. C. Crawford (Stony Brook University), were transfected in each of the appropriate reporter assays. Luciferase activity was determined 24 hours posttransfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Each reporter assay was performed in duplicate. The results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments and are presented as the relative fold increase (relative light units, RLU) over mock-transfected cells (set at a value of 1).

For siRNA transfections, two siRNA constructs targeting rat caspase 3 (NM_012922) were purchased from Ambion (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX). The siRNA sequences are siRNA#1: 5′-CCUUACUCGUGAAGAAAUUtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-AAUUUCUUCACGAGUAAGGtc-3′ (antisense); siRNA#2: 5′-GCAGUUACAAAAUGGAUUAtt-3" (sense) and 5′-UAAUCCAUUUUGUAACUGCtg-3′ (antisense). Tsc2−/− cells at 20% confluence were transfected with 50 nM of control or caspase 3 siRNA using Lipofectamine PLUS transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Three days posttransfection, samples were treated with 1 μM STS for 4.5 hours to induce nonadherence. Cells were harvested with PBS and then lysed with 0.5% NP40 buffer. Protein content was determined by BCA assay. Samples were analyzed by 7 and 12.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to immobilon, and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins with a 1:1,000 dilution of primary antibody solution. All Westerns were probed with mouse or rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antisera at a dilution of 1:2,000 with proteins detected by ECL.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 3 × 107 adherent and nonadherent cells according to the protocol from RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA (2 μg for GAPDH and 3 μg for MMP7) was subjected to RT-PCR according to the manufacturer's protocol (RETROscript; Ambion) for message analysis. RT-PCR of MMP7 was performed with a nested two-step amplification strategy. The RT reaction was performed with 1.5 mM MgCl2. RT product (5 μl) was then subjected to the following initial PCR cycling parameters: one cycle at 95°C for 1 minute, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 1.5 minute, 72°C for 1 minute, with final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes using external primers. Initial PCR product (10 μl) was then subjected to the PCR cycling parameters as described previously using nested primers. Final products were analyzed by 2.0% agarose gel. The primer sequences used were rat GAPDH (414 bp) 5′-TGCATCCTGCACCACCAACTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AATGCCAGCCCCAGCATCAAAG-3′ (antisense), external primers for rat MMP7 5′-GGAAAGCTGTCCCCCCGTGTCATG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTCATCCTTGTCAAAGTGAGCATC-3′ (antisense), and nested primers for rat MMP7 (244 bp) 5′-GAATTCTCACTAATGCCAAACAGT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTGTTTCCTGGCCCATCAAATGGG-3′ (antisense).

Invasion Assays

For collagen gel invasion assays, 2 ml of collagen substrate (80% PureCol [INAMED], 10% 10× PBS, 9% FBS, 1% PenStrep) were aliquoted per 60-mm plate. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours to allow for collagen polymerization. A total of 2.5 × 105 cells were added with 3 ml of DMEM-F12+10% FBS to each plate. Every 2 to 3 days, samples were replenished with fresh DMEM-F12+10% FBS. Pictures were taken at 2 weeks after the addition of cells.

For epithelial feeder cell invasion assays, human epithelial A431 cells (ATCC) were plated at high density onto 60-mm plates containing glass coverslips. After A431 cells had reached confluence, 4 × 105 cells (Tsc2+/+ [4], Tsc2−/− [8], or nonadherent Tsc2−/− [8] cells) were added with further incubation at 37°C for 2 to 5 days. Samples were supplemented with fresh DMEM-F12+10% FBS daily. At 2 and 5 days postaddition, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for confocal immunofluorescence analysis. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Leica SP1/MP or a Zeiss 510 META confocal microsope. Tsc2+/+ and Tsc2−/− cells were visualized by the use of smooth muscle actin antisera (Sigma), which does not recognize A431 cells. TOPRO3 (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) was used to detect the nuclei from all cells. Media from each sample was harvested 2 days after the addition of Tsc2+/+ or Tsc2−/− cells and then examined by MMP7 immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE/Western immunoblot analysis for the presence of secreted, active MMP7 (Calbiochem cat# IM47L).

Inhibition of MMP7 activity was performed using two different antibodies targeting MMP7 (Millipore cat# AB8117 and Chemicon cat# MAB13414) (20). Increasing amounts of both antibodies (with each antibody at concentrations of 0, 0.25, and 1.0 μg/ml) and 1.0 × 105 nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells were added simultaneously to collagen coated plates prepared as described previously. Cells were re-fed 24 hours later and then every 2 to 3 days with fresh DMEM-F12+10% FBS. Twenty-four days postaddition, the invasive colony number of each sample was assessed. The results shown represent the average number of collagen-cleared areas counted per field (with a minimum of five fields counted) of two independent experiments.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel 2004 using Student's t test.

RESULTS

Tsc2−/− Fibroblasts Exhibit Loss of Contact Inhibition and Proliferate as Nonadherent Cells

To analyze the effects of tuberin on cell proliferation, we compared the growth rates of two independent Tsc2−/− rat embryonic fibroblast cell lines (EEF-8, EEF-4a) to an isogenic wild-type rat embryonic fibroblast cell line (EEF-4), all derived from the Eker rat model of TSC (15). In the subconfluent state, the mutant and wild-type cells grew at similar rates (data not shown), but after confluence, the Tsc2−/− cells proliferated significantly faster than wild-type cells (rate of proliferation: EEF-8: 3,850 ± 700 cells/h, EEF-4a: 3,541 ± 700 cells/h; EEF-4: 914 ± 18 cells/h; P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). When these samples were subjected to cell cycle kinetic analyses by BrdU-Hoechst flow cytometry (18), the proportion of cells undergoing active cell cycling was significantly higher for the postconfluent Tsc2−/− fibroblasts compared with wild-type cells (Figure 1B, right panel). Consistent with the cell proliferation data, no difference was found between wild-type and mutant cells during the subconfluent period (Figure 1B, left panel). At confluence, the mutant fibroblasts detached from adjacent cells and continued to grow in suspension; this was not observed in the wild-type cells (Figure 1C). By the third day after reaching confluence, more than 25% of the total Tsc2−/− cell population was in suspension in the media.

Figure 1.

Tsc2-null cells produce a proliferative nonadherent (N-Adh) subpopulation at confluence. (A) After confluence, Tsc2−/− cells (EEF-8 [red] and EEF-4a [green]) proliferated faster than wild-type cells (EEF-4 [black]). Cells were manually counted at the indicated time points after confluence. Average error bars ± 0.1. (B) Cell proliferation as determined by BrdU-Hoechst flow cytometry was analyzed for subconfluent (left graph) and postconfluent (right graph) wild-type (EEF-4 [black]) and Tsc2 mutant (EEF-8 [red]; EEF-4a [green]) cells over 72 hours. BrdU quenching of Hoechst fluorescence as compared with ethidium bromide fluorescence identified actively cycling cells. The y axis represents the proportion of cells that have passed through the first cell cycle relative to the total number of cells. Average error bars ± 0.1. (C) Morphology of postconfluent cultures of Tsc2+/+ and Tsc2−/− fibroblasts. Arrows indicate refractile cells that have detached from the plate. (D) N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells (8 and 4a) are viable as determined by trypan blue exclusion assays. Each cell viability assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments, presented as the percentage of viable cells. In addition, replated N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells grow in foci-like colonies (right panels). (E) N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells undergo multiple rounds of cell proliferation as determined by BrdU-Hoechst flow cytometry. At confluence, BrdU was added to the media for 72 hours. Nonadherent cells were collected and processed for analyses. Plots depict the number of cells versus Hoechst intensity and show the distribution of cells in G0/G1, G1′, and G1" phases representing the relative proportion of cells in the first, second, and third cell cycle postlabeling, respectively.

To determine the viability of the detached Tsc2 mutant cells, trypan blue exclusion assays were performed. The results show that approximately 75% of the nonadherent Tsc2−/− (EEF-8 and EEF-4a, herein referred to as 8 and 4a, respectively) cells were found to be viable (Figure 1D). Upon replating and further incubation for 3 weeks, the nonadherent cells reattached and formed foci-like colonies (Figure 1D, right panels), indicating that these cells remained viable in the nonadherent state and have the ability to reattach and propagate. The nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells were further analyzed by BrdU-Hoechst flow cytometry to directly probe their cell cycle activity. Figure 1E shows that these cells incorporated BrdU to quench the fluorescence of the Hoechst dye over three consecutive cell cycles. At 72 hours postconfluence, 74% of EEF-8 and 75% of EEF-4a cells have entered into their second and third cell cycles (indicated by G1′ and G1″, respectively). These data strongly indicate that the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells are viable and actively growing. Cells lacking functional tuberin exhibit loss of contact inhibition and proliferate as nonadherent cells.

Nonadherent Tuberin-Null Cells Express Truncated β-Catenin

To further characterize the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells, we examined the expression of β-catenin on the basis of our previous studies showing a functional link between the TSC1/TSC2 complex and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (21, 22). Upon confluence, wild-type and Tsc2 mutant fibroblasts up-regulated total β-catenin levels; this differs from our previous observations in epithelial cells where higher β-catenin expression was found in the Tsc2-mutant cells, suggesting that a cell-type functional difference may exist between fibroblasts and epithelial cells (Figure 2A; compare lane 4 with lanes 5 and 6). However, we identified faster mobility bands in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells that were detected by the anti–β-catenin antibody suggestive of truncated fragments (Figure 2A, lanes 7 and 8). To confirm the identity of these bands, cell lysates from the nonadherent Tsc2 mutant cells were immunoprecipitated with the β-catenin antibody and subjected to mass spectrometry analyses. Sequencing of the tryptic fragments was found to be identical to the peptide sequence of β-catenin. Thus, the faster migrating immunoreactive bands expressed in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells represent cleaved products of β-catenin.

Figure 2.

Viable Tsc2-mutant cells express truncated β-catenin. (A) N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells (8 and 4a) express truncated forms of β-catenin (upper panel, lanes 7 and 8). Sub = subconfluent; Conf = confluent cell cultures. Expression of β-actin serves as a loading control (lower panel). (B) N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells were sorted by flow cytometry technique to isolate annexin V−, PI−; annexin V+, PI−; and annexin V+, PI+ cell populations. Lysates were blotted for β-catenin (upper panel). The Coomassie-stained gel in the lower panel serves as a loading control. The graph represents the cell viability associated with each sorted sample as determined by trypan blue exclusion method. Each cell viability assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments, presented as a percentage of viable cells. *P < 0.01. (C) β-catenin proteins identified in the Tsc2-null fibroblasts resemble the forms of β-catenin expressed in renal tumor–derived cell lines ERC18M and LEF2. Upper panel, β-catenin immunoblot; lower panel, β-actin immunoblot; lanes 1 and 2, Tsc2−/− (8); lanes 3 and 4, ERC18M; lanes 5 and 6, LEF2 lysate samples. Adh = adherent; N-Adh = nonadherent cell cultures. (D) Kidney tumors from Eker rats overexpress full-length and truncated forms of β-catenin (upper panel, lanes 3, 5, and 7). Middle panel, longer exposure of β-catenin immunoblot. +/+, normal human kidney tissue; +/−, normal kidney tissue (N) from heterozygote rat (Eker rat); −/−, kidney tumor tissue (T) from heterozygote rat (Eker rat). (E) Apoptosis is minimal or undetectable in untreated kidney tumor samples. Representative TUNEL staining from Eker rat kidney tumors. TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells are shown in brown.

Because not all of the nonadherent cells were viable (see Figure 1D), we examined whether the truncated forms of β-catenin identified in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells originated from a viable or nonviable cell population. These cells were divided into three groups by flow cytometry based on their staining properties with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI). Early apoptotic cells can be detected through the use of annexin V staining because annexin V has a high affinity for externally localized phosphatidylserine residues that accompany the morphologic changes in the plasma membrane during the early phase of apoptosis. As cells continue to apoptose, nuclear changes occur after the degradation of the plasma membrane, allowing PI to enter the nucleus. Therefore, cells can be sorted into the following fractions: (annexin V−, PI−), (annexin V+, PI−), and (annexin V+, PI+). After sorting, cells were lysed and analyzed for the expression of β-catenin. Only the (annexin V−, PI−) and (annexin V+, PI−) nonadherent cell fractions contained truncated β-catenin proteins (Figure 2B, upper panel, lanes 2 and 3). Full-length β-catenin was undetectable in these samples. Truncated forms of β-catenin were not expressed in the (annexin V+, PI+) cell fraction (Figure 2B, upper panel, lane 4). This latter fraction had approximately 5% of cells that were deemed viable based on trypan blue exclusion assay (Figure 2B, graph). In contrast, the annexin V−, PI−, and annexin V+, PI− cell samples contained 95 and 87% viable cells, respectively. Together, these results demonstrate that the truncated forms of β-catenin originated from the viable, nonadherent Tsc2-null cell population and not from the small pool of “dying” cells under our experimental conditions.

Truncated β-Catenin Is Expressed in Eker Rat Renal Tumors

To further confirm that the expression of truncated β-catenin is not an artifact of the cell lines used, we turned to another set of independently derived Tsc2−/− cell lines obtained from the Eker rat model of renal epithelial tumors. The ERC18M and LEF2 renal tumor cells expressed predominantly full-length β-catenin in the adherent phase of their in vitro growth (Figure 2C, upper panel, lanes 3 and 5). At confluence, both cell lines exhibited loss of contact inhibition and detached from the plate to grow in suspension similar to the behavior observed in the EEF-4a and EEF-8 Tsc2-null fibroblasts (data not shown). The nonadherent ERC18M and LEF2 cells expressed truncated β-catenin of the same molecular mass as that found in the fibroblast lines (Figure 2C, upper panel; compare lanes 4 and 6 with lane 2). Next, we examined paired samples of renal tumors and adjacent nontumor kidney tissues from the Eker rat. Tumor samples from three different animals overexpressed β-catenin protein compared with adjacent normal kidneys (Figure 2D, upper panel, lanes 3, 5, and 7). All kidney tumor samples expressed truncated forms of β-catenin similar in molecular mass to that found in the nonadherent EEF-8 cells (Figure 2D, upper panel; compare lanes 3, 5, and 7 with lane 8). Wild-type kidney expressed predominantly full-length β-catenin (Figure 2D, upper panel, lane 1), whereas Tsc2+/− kidneys adjacent to the tumors showed full-length and truncated β-catenin (Figure 2D, middle panel, lanes 2, 4, and 6). The latter observation is likely due to multiple small tumors throughout the heterozygous kidneys. Next, we examined the extent of apoptosis in the primary tumors to determine if apoptotic cells could be the source of truncated β-catenin. Figure 2E shows that untreated kidney tumors had a minimal degree of apoptosis as measured by TUNEL assay. This implies that truncated β-catenin in the tumors is not derived from apoptotic cells but rather is expressed in the viable tumor cells. Together, our in vitro observations from four independently derived Tsc2-null cell lines plus our in vivo data from the Eker rat tumors strongly suggest that the viable Tsc2−/− cells are the primary source of truncated β-catenin.

Caspase 3 Activity Contributes to β-Catenin Cleavage

We sought to identify the source of truncated β-catenin in the Tsc2 mutant cells. Previous reports have demonstrated that β-catenin is cleaved by caspases 3, 6, and 8 (23, 24). To investigate whether one or more of these caspases were responsible for the truncated β-catenin proteins, we first used STS to induce caspase activity in the wild-type cells and compared their β-catenin products with those found in the untreated, nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells and with STS-treated, adherent Tsc2−/− cells. In wild-type cells, STS treatment led to the appearance of cleaved β-catenin fragments that were indistinguishable in mass to those found in the Tsc2-null cells (Figure 3A, upper panel, lane 2). However, the majority of the STS-treated wild-type cells were not viable compared with STS-treated Tsc2−/− cells (Figure 3A, graph). These observations highlight the importance of the loss of Tsc2 in the generation of viable nonadherent cells. Based on in vitro caspase assays, STS activated caspase 3 to a much greater extent than caspase 6 or caspase 8 in the Tsc2+/+ cells (Figure 3B). Similarly, untreated Tsc2−/− cells possessed significantly higher levels of caspase 3 activity but not caspase 6 or caspase 8 activity compared with wild-type cells, although the level of caspase 3 activity was much less than that induced by STS treatment in wild-type cells. This activity was maintained in the nonadherent cells (Figure 3C, graph). The level of caspase 3 activity correlated closely with cleaved β-catenin expression. Treatment of the nonadherent Tsc2-null cells with a general caspase inhibitor, ZVAD-FMK, prevented the appearance of truncated β-catenin proteins (data not shown), but, more specifically, treatment with two independent caspase 3 siRNA in the Tsc2−/− cells significantly reduced the relative amount of cleaved β-catenin products and MMP7 in parallel with the down-regulation of caspase 3 expression (Figure 3D). Together, these results suggest that the loss of Tsc2 predisposes cells to density-dependent activation of caspase 3, which leads to cleavage of β-catenin while maintaining cell viability.

Figure 3.

Caspase 3 activity induces cleavage of β-catenin in Tsc2-null cells. (A) Staurosporine (STS) treatment promotes the cleavage of β-catenin in Tsc2+/+ cells. Cells at 90% confluence were treated for 18 hours +/− 1 μM STS, and cell lysates were processed for immunoblot analysis of β-catenin. Expression of β-actin serves as a loading control (lower panel). Lane 1, untreated Tsc2+/+ (4) cells; lane 2, STS-treated Tsc2+/+ (4) cells; lane 3, untreated N-Adh Tsc2−/− (8) cells; lane 4, STS-treated Adh Tsc2−/− (8) cells; lane 5, untreated N-Adh Tsc2−/− (4a) cells; lane 6, STS-treated Adh Tsc2−/− (4a) cells. The graph shows the proportion of viable cells as determined by trypan blue exclusion assays in comparison to Tsc2+/+ (4) cells treated with STS. Each cell viability assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments, presented as a percentage of viable cells. *P < 0.01. (B) In vitro caspase assays illustrate the effects of STS on caspase 3, 6, and 8 activities in the Tsc2+/+ (4) cells. Caspase activities of the Tsc2−/− (8, 4a) cells are also shown for comparison. *P < 0.05. (C) Tsc2−/− cells accumulate caspase 3 activity when Conf or N-Adh (graph). *P < 0.05. Corresponding immunoblots show the expression of β-catenin (upper panel) and β-actin loading control (lower panel). (D) siRNA mediated depletion of caspase 3 results in the reduction of cleaved β-catenin and MMP7 proteins in Tsc2−/− cells. Cells were transfected with 50 nM of control siRNA (lane 1) or one of two caspase 3 siRNA (lanes 2 and 3). Lysates were examined by immunoblot analysis. Upper panel, caspase 3; upper middle panel, β-catenin; lower middle panel, MMP7; lower panel, β-actin immunoblots. Expression of β-actin serves as a loading control. The graph shows the relative expression of caspase 3, cleaved β-catenin, and MMP7 proteins as compared with full-length β-catenin and β-actin proteins expressed as fold change.

Cleaved β-Catenin Products Are Transcriptionally Active

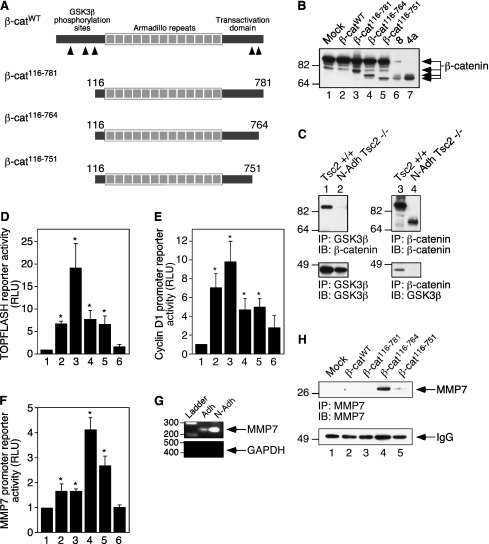

Previous work has shown that β-catenin contains five caspase 3 cleavage sites, with three residing within the N-terminus and two within the C-terminus (24). Based on the apparent molecular mass of the cleaved products (∼72 and 70 kD) and the mapped caspase 3 cleavage sites, three β-catenin constructs were designed for further examination (Figure 4A; β-cat116–781, β-cat116–764, and β-cat116–751). By Western immunoblot analysis, Figure 4B shows that two of these deletion constructs (lanes 4 and 5; β-cat116–764 and β-cat116–751, respectively) resemble the products found in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells (lanes 6 and 7).

Figure 4.

Cleaved forms of β-catenin are transcriptionally active. (A) Schematic of β-catenin constructs with caspase 3 cleavage sites denoted by black arrowheads. (B) Expression of β-catenin mutants. Lane 1, mock transfection; lane 2, β-catWT; lane 3, β-cat116–781; lane 4, β-cat116–764; lane 5, β-cat116–751; lane 6, N-Adh Tsc2−/− (8) cells; lane 7, N-Adh Tsc2−/− (4a) cells. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments show that truncated β-catenin proteins identified in N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells do not associate with GSK3β (upper and lower panels, lanes 2 and 4). Left panels, GSK3β immunoprecipitates; right panels, β-catenin immunoprecipitates; upper panels, β-catenin immunoblots; lower panels, GSK3β immunoblots. (D) TOPFLASH reporter assays demonstrate that β-catenin mutants maintain significant transcriptional activity (compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). (E) Cyclin D1 reporter assays demonstrate that β-catenin mutants maintain some activities (compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). (F) MMP7 reporter assays show that β-catenin mutants are more active than wild-type β-catenin (compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). Lane 1, mock; lane 2, β-catWT; lane 3, β-cat116–781; lane 4, β-cat116–764; lane 5, β-cat116–751; lane 6, β-catWT and dominant negative TCF-4. Each reporter assay was performed in duplicate, and the results shown represent the mean values ± SEM of three independent experiments, presented as the relative fold increase (relative light units, RLU) over mock-transfected cells (set at a value of 1). *P < 0.05 as compared with mock samples. (G) RT-PCR analysis demonstrates the up-regulation of MMP7 mRNA in N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells (upper panel). Expression of GAPDH serves as a control for RNA expression (lower panel). (H) β-catenin mutant overexpression induces MMP7 protein expression (lanes 4 and 5). HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs: lane 1, mock transfection; lane 2, β-catWT; lane 3, β-cat116–781; lane 4, β-cat116–764; lane 5, β-cat116–751. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with MMP7 antibody to detect MMP7 protein (upper panel, lanes 4 and 5). Lower panel, Western immunoblot of IgG bands of MMP7 immunoprecipitated samples serves as a loading control.

N-terminally truncated forms of β-catenin have been shown to behave in a constitutively active manner because they lack the sites required for binding and phosphorylation by GSK3β, a key event that regulates β-catenin turnover (25–28). We predicted that the N-terminal deletion of β-catenin by caspase 3 should render the truncated protein active and incapable of interacting with GSK3β. The β-catenin mutants found in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells were unable to associate with GSK3β in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 4C, upper and lower panels, lanes 2 and 4).

Luciferase reporter assays were performed to address the transcriptional activity of the β-catenin deletion mutants. Results from TOPFLASH assays showed that β-cat116–764 and β-cat116–751 remained as active as wild-type β-catenin (Figure 4D; compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). Expression of the β-cat116–781 construct showed a substantial increase in TOPFLASH-dependent transcription (Figure 4D, lane 3), as suggested by previous studies (29). Cyclin D1 is a downstream target of β-catenin transcriptional activity (29), and in cyclin D1 reporter assays, β-cat116–764 and β-cat116–751 retained transcriptional activity toward the cyclin D1 promoter, but at a level lower than that of wild-type β-catenin (Figure 4E; compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). MMP7 is also a downstream target of β-catenin (30), and, in reporter assays using the MMP7 promoter, β-cat116–764, and to a lesser extent β-cat116–751, maintained considerable transcriptional activity toward the target gene MMP7 and more so than wild-type β-catenin (Figure 4F; compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 2). This suggests that nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells may specifically express MMP7. We used RT-PCR to confirm that MMP7 was actively transcribed in the nonadherent cells. Nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells contained substantially more MMP7 mRNA than their adherent counterpart (Figure 4G). Forced expression of β-catenin116–764, and to a lesser extent β-catenin116–751, led to higher levels of MMP7 protein expression (as 28 kD proenzyme) than wild-type β-catenin and β-catenin116–781 (Figure 4H; compare lanes 4 and 5 with lanes 2 and 3), correlating well with their MMP7 promoter activities. Overall, these results demonstrate that the truncated forms of β-catenin are transcriptionally active and cannot be regulated by GSK3β. These active β-catenin mutants are responsible for MMP7 expression in the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells.

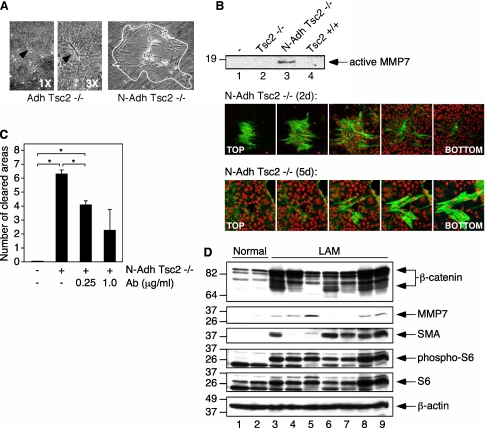

Nonadherent Tuberin-Null Cells Secrete MMP7 and Are Invasive

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play an important role in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix during physiological and pathological processes (31). Unregulated degradation of extracellular matrix components facilitates cell invasion. It has become apparent that various MMPs are overexpressed in several pulmonary disorders (32). It has also been demonstrated that MMP2, and to a lesser extent MMP9, are up-regulated in the lungs of patients with LAM (33, 34). MMP7 is one of the few MMPs to be produced by tumor cells and has been shown to be overexpressed in several types of invasive cancers (35). To determine if nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells are invasive due to MMP7 production, two types of cell invasion assays were performed. First, collagen gel invasion assays were used because collagen is a substrate for MMP7 (in addition to MMP2 and MMP9) (36). It appeared that nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells attached to the substrate as a colony of cells and then invaded and spread throughout the collagen matrix (Figure 5A, right panel). Adherent Tsc2−/− cells and adherent Tsc2+/+ cells were also used in these cell invasion assays. Figure 5A (left panel) depicts a single adherent Tsc2−/− cell that was attached to the collagen substrate yet remained incapable of invasion. Tsc2+/+ cells were also incapable of invading a collagen matrix (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Nonadherent tuberin-null cells are invasive. (A) Collagen gel invasion assays show that N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells are invasive (right panel). The white outline depicts the boundary of the collagen gel area cleared by N-Adh Tsc2−/− invasive cells. The left panel depicts an Adh Tsc2−/− cell attached to the collagen matrix (denoted by black arrowhead) without any effects on the underlying collagen gel. The middle panel shows the same cell enlarged 3×. (B) Feeder cell invasion assays demonstrate that N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells invade epithelial cell layers and secrete cleaved, active MMP7. Lane 3 shows the expression of active MMP7 from immunoprecipitated media at 2 days postaddition. Lane 1, feeder cells; lane 2, feeder cells + Adh Tsc2−/− cells; lane 3, feeder cells + N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells; lane 4, feeder cells + Tsc2+/+ cells. Upper confocal images depict a N-Adh Tsc2−/− cell colony invading epithelial cell layers by Day 2 (2 days). Lower images show the continued invasion of N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells through a feeder layer by Day 5 (5 days). Green, smooth muscle actin staining of the N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells; red, nuclei visualized with TOPRO3 in all cells. (C) Inhibition of MMP7 activity blocks the invasion of N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells in collagen gel invasion assays. N-Adh Tsc2−/− cells were incubated with a combination of two MMP7 antibodies, each at the following concentrations: 0, 0.25, 1.0 μg/ml. The results shown represent the average number of collagen areas cleared by invasive colonies counted per field (with a minimum of five fields counted) of two independent experiments. *P < 0.05. (D) Analysis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis tissue samples demonstrates the presence of cleaved β-catenin and MMP7 (lanes 3–9). Immunoblot analyses of lung lysates using the indicated antibodies. Normal lung tissues are represented in lanes 1 and 2.

Second, epithelial feeder cell invasion assays were used because E-cadherin is a substrate for MMP7 (as opposed to MMP2 and MMP9) (37). When nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells were added to an epithelial feeder cell layer, they secreted active MMP7 (cleaved 18 kD protein) into the cell media (Figure 5B, lane 3). The addition of adherent Tsc2−/− or Tsc2+/+ cells did not induce the expression of MMP7 into the cell media (Figure 5B, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). Alhough these cells were able to attach to the feeder cell layer, they remained unable to invade (data not shown), which is consistent with the data from the collagen gel invasion assays. As visualized by confocal microscopy, nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells formed colonies during the invasion process and superficially invaded the top layer of the feeder cells within 2 days (Figure 5B; N-Adh Tsc2−/− [2 d]). Three days later, the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells completed traveling through the feeder cells and formed colonies beneath the feeder cell layer (Figure 5B; N-Adh Tsc2−/− [5 d]). Together, these results show that the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells have acquired the ability to secrete MMP7 and invade a foreign substrate.

To further investigate the role of caspase 3 in the production of MMP7 proteins, we used siRNA techniques to deplete caspase 3. Down-regulation of caspase 3 expression using two independent siRNA constructs led to a decrease in cleaved β-catenin and MMP7 proteins (Figure 3D, lane 2). These results are consistent with the role of caspase 3 in the expression of truncated forms of β-catenin and its transcriptional target MMP7 in the Tsc2−/− cells. To address the requirement for MMP7 in Tsc2−/− cell invasion, MMP7 activity was inhibited with the addition of two different functional antibodies specific for MMP7. Both antibodies bind to the active form of MMP7. In collagen gel invasion assays, the addition of these antibodies resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in invasive colony count (Figure 5C), suggesting that MMP7 activity is necessary to promote Tsc2−/−–dependent cell invasion.

LAM Tissues Express Cleaved β-Catenin

To explore the clinical relevance of our findings, we examined the expression of β-catenin and MMP7 in human LAM tissues. Seven samples were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange without any clinical identifier except for the diagnosis of LAM. Western blot analyses of the tissue lysates are shown in Figure 5D. All LAM tissues have overexpression of β-catenin compared with normal lung, and six of seven samples expressed truncated β-catenin to a variable degree (Figure 5D, upper panel, lanes 3, 4, and 6–9). Five cases each demonstrated expression of MMP7 and smooth muscle actin, whereas phospho-S6, a marker of mTORC1 activity, was present in all LAM but not normal lung tissues. Although some samples do not demonstrate a direct correlation between the observed levels of cleaved β-catenin and MMP7, this likely reflects the vast heterogeneity in tissue sampling and processing. However, none of the proteins except β-catenin showed truncated fragments to suggest nonspecific tissue degradation. These findings from clinical samples are highly supportive of our in vitro data and show for the first time the presence of cleaved β-catenin and MMP7 in human TSC-related pathology. One limitation of our studies is the use of lysates from whole lung tissues that included LAM and non-LAM cells; therefore, the possibility exists for the “bystander” cells as the source of the observed cleaved β-catenin although immunohistochemical analyses suggest a strong correlation between the β-catenin–expressing and smooth muscle actin-expressing LAM cells (data not shown). Future studies using immunohistochemistry-guided microdissection-based proteomic analysis may help to confirm our results.

DISCUSSION

Our study describes a possible mechanism of LAM development involving nonadherent tuberin-null cells. In this report we show that the Tsc2−/− cells exhibit a loss of contact inhibition, proliferate as nonadherent cells, and display invasive growth behavior. In addition, these cells express truncated forms of β-catenin. These forms of β-catenin are transcriptionally active in reporter assays and are unregulated by GSK3β (e.g., loss of ability to associate with GSK3β). β-catenin is found mutated in several types of cancer and particularly in the context of metastatic disease (38). In such cases, the N-terminus of β-catenin is typically found altered because this domain is necessary to regulate β-catenin degradation. The absence of this domain or mutation of specific residues within this domain results in a stabilized β-catenin protein with equal or greater transcriptional activity than wild-type β-catenin (25–28). One downstream target of mutant β-catenin activity is MMP7, a key component of cell invasion (39). MMP7 is one of the few MMPs produced by tumor cells and found overexpressed in several types of invasive cancers (35, 40). Here we show that nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells secrete MMP7 and prove invasive in collagen and feeder cell invasion assays. Our findings correlate well with a previous study showing that primary LAM cells exhibit increased invasiveness in collagen gel invasion assays (41). Here we are also able to demonstrate that the inhibition of MMP7 activity by antibody incubation substantially decreases the ability of the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells to invade collagen matrices. Furthermore, the expression of the β-catenin mutant β-cat116–764 significantly enhances the transcription of a MMP7 reporter and expression of MMP7 protein, as compared with wild-type β-catenin, demonstrating that nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells become invasive due to cleaved β-catenin activity and the production of MMP7.

Using in vitro caspase assays, we found that the induction of caspase activity, in particular caspase 3, promotes the expression of truncated forms of β-catenin. In contrast, the suppression of caspase 3 activity inhibited the expression of truncated forms of β-catenin and MMP7. Caspase 3 activity was found to be increased in the Tsc2-null cells especially under confluent and nonadherent conditions, but these cells remained largely viable. It appears that a limited amount or threshold of caspase activity is required to initiate the cleavage of β-catenin (∼20-fold over basal levels) but without forcing the cells to complete an apoptotic program. It has been suggested that a low constitutive level of caspase activity may be necessary to carry out cellular regulatory processes (42). Our results extend this concept in the Tsc2-null cells to acquire new biologic activity (e.g., invasion) through caspase-mediated cleavage of β-catenin. Our findings are consistent with a recent report demonstrating that caspase 3 induces N- and C-terminal cleavage of β-catenin in G401 Wilms' tumor cells. These “floating cells” remained viable, were able to reattach to cell culture plates, and demonstrated a weakened ability for cell aggregation, suggesting enhanced cell motility (43). An unresolved question remains as to why the viable, nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells have enhanced caspase 3 activity. One possibility is that mutant β-catenin activity alone allows these cells to escape cell death through some form of feedback mechanism. Alternatively, the activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in the Tsc2−/− cells may serve to induce cell survival even in the presence of limited caspase activity. Recently it has been demonstrated that the loss of TSC2 activates the unfolded protein response, a pathway that plays a significant role in the promotion of cell survival during conditions of cellular stress but can also lead to the activation of caspase 3 (44). This avenue of research warrants further investigation.

We showed that the presence of cleaved β-catenin is not an in vitro artifact. In a TSC animal model, we found evidence of cleaved β-catenin in spontaneously occurring renal tumors. Eker rat renal tumors and human AMLs are dissimilar in phenotype but are physiologically analogous due to the activation of the mTOR and β-catenin signaling pathways (22, 45). It has been suggested that the nonadherent Tsc2−/− cells may originate from tuberin-deficient hamartomas, such as AMLs, and travel to the lung where they invade the lung parenchyma in a “benign mestastasis” model (12). Indeed, we provide evidence of cleaved β-catenin and MMP7 expression in human LAM tissues. Combining this with the results of our earlier studies showing the negative regulatory function of TSC1/TSC2 in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and the aberrant expression of β-catenin targets in LAM (21, 22), the cumulative evidence strongly supports the role of β-catenin in the pathogenesis of LAM. Future studies will address the association between cleaved β-catenin, MMP7, and clinical outcome.

In summary, our observations provide new evidence that the Tsc2−/− cells can produce cleaved β-catenin that enhances MMP7 expression to promote cell invasion. These results highlight the potential for targeting the caspase 3 and β-catenin/MMP7 pathways as novel therapeutic approaches in LAM and other TSC-related disorders.

Acknowledgments

DNA sequencing services were provided by the UW DNA Sequencing Facility at the University of Washington. Confocal microscopy was performed at the Keck Microscopy Facility at the University of Washington. Flow cytometry cell sorting services and cell cycle analyses were provided by the Flow Cytometry Facility at the University of Washington. Mass spectrometry analyses were provided by the University of Washington Medicinal Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Center. LAM tissue was obtained through the University of Washington Medical Center and the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI).

This work was supported by grants from the LAM Foundation (E.A.B.) and NIH grants CA77882 and CA102662 (R.S.Y.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0335OC on December 30, 2009

Author Disclosure: E.A.B. has received sponsored grants from the LAM Foundation ($50,000–$100,000). R.S.Y. has received grants from the NIH ($100,000+) and served on the LAM Foundation Advisory Board. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kelly J, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Med Sci 2001;321:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:810–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:6085–6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Chromosome 16 loss of heterozygosity in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1537–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack F, Brody A, Meyer C, Leonard J, Chuck G, Dabora S, Sethuraman G, Colby TV, Kwiatkowski DJ, Franz DN. Pulmonary cysts consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis are common in women with tuberous sclerosis: genetic and radiographic analysis. Chest 2002;121:61S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez MR. Definition and criteria for diagnosis: tuberous sclerosis complex. Tuberous sclerosis complex: developmental perspectives in psychiatry, 3rd edition. Gomez MR, Sampson JR, Whittemore VH, editors. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 10–24.

- 7.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int 2004;66:924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Callaghan FJ, Noakes MJ, Martyn CN, Osborne JP. An epidemiological study of renal pathology in tuberous sclerosis complex. BJU Int 2004;94:853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Pauw RA, Boelaert JR, Haenebalcke CW, Matthys EG, Schurgers MS, De Vriese AS. Renal angiomyolipoma in association with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;41:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehler A, Speich R, Russi EW, Weder W. Lung transplantation for lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1275–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien JD, Lium JH, Parosa JF, Deyoung BR, Wick MR, Trulock EP. Lymphangiomyomatosis recurrence in the allograft after single-lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:2033–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karbowniczek M, Astrinidis A, Balsara BR, Testa JR, Lium JH, Colby TV, McCormack FX, Henske EP. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bittmann I, Rolf B, Amann G, Lohrs U. Recurrence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis after single lung transplantation: new insights into pathogenesis. Hum Pathol 2003;34:95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crooks DM, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, DeCastro RM, McCoy JP Jr, Wang JA, Kumaki F, Darling T, Moss J. Molecular and genetic analysis of disseminated neoplastic cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:17462–17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones KA, Jiang X, Yamamoto Y, Yeung RS. Tuberin is a component of lipid rafts and mediates caveolin-1 localization: role of TSC2 in post-Golgi transport. Exp Cell Res 2004;295:512–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin F, Wienecke R, Xiao GH, Maize JC Jr, DeClue JE, Yeung RS. Suppression of tumorigenicity by the wild-type tuberous sclerosis 2 (Tsc2) gene and its C-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:9154–9159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeung RS, Xiao GH, Jin F, Lee WC, Testa JR, Knudson AG. Predisposition to renal carcinoma in the Eker rat is determined by germ-line mutation of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:11413–11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poot M, Rosato M, Rabinovitch PS. Analysis of cell proliferation and cell survival by continuous BrdU labeling and multivariate flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Cytom 2001;7:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce RH, Campbell JS, Stephenson AB, Franklin CC, Chaisson M, Poot M, Kavanagh TJ, Rabinovitch PS, Fausto N. Disruption of redox homeostasis in tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis in a murine hepatocyte cell line. Am J Pathol 2000;157:221–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen P, McGuire JK, Hackman RC, Kim K-H, Black RA, Poindexter K, Yan W, Liu P, Chen AJ, Parks WC, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 moderates airway re-epithelialization by regulating matrilysin activity. Am J Pathol 2008;172:1256–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak BC, Takemaru K, Kenerson HL, Moon RT, Yeung RS. The tuberin-hamartin complex negatively regulates beta-catenin signaling activity. J Biol Chem 2003;278:5947–5951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak BC, Kenerson HL, Aicher LD, Barnes EA, Yeung RS. Aberrant beta-catenin signaling in tuberous sclerosis. Am J Pathol 2005;167:107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van de Craen M, Berx G, Van den Brande I, Fiers W, Declercq W, Vandenabeele P. Proteolytic cleavage of beta-catenin by caspases: an in vitro analysis. FEBS Lett 1999;458:167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinhusen U, Badock V, Bauer A, Behrens J, Wittman-Liebold B, Dorken B, Bommert K. Apoptosis-induced cleavage of beta-catenin by caspase-3 results in proteolytic fragments with reduced transactivation potential. J Biol Chem 2000;275:16345–16353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, Fiol C, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science 1996;272:974–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orford K, Crockett C, Jensen JP, Weissman AM, Byers SW. Serine phosphorylation-regulated ubiquitination and degradation of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 1997;272:24735–24738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barth AI, Pollack AL, Altschuler Y, Mostov KE, Nelson WJ. NH2-terminal deletion of beta-catenin results in stable colocalization of mutant beta-catenin with adenomatous polyposis coli protein and altered MDCK cell adhesion. J Cell Biol 1997;136:693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science 1997;275:1752–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature 1999;398:422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford HC, Fingleton BM, Rudolph-Owen LA, Goss KJ, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin is a target of beta-catenin transactivation in intestinal tumors. Oncogene 1999;18:2883–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemaitre V, D'Armiento J. Matrix metalloproteinases in development and disease. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2006;78:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro SD, Senior RM. Matrix metalloproteinases: matrix degradation and more. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;20:1100–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayashi T, Fleming MV, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Liotta LA, Moss J, Ferrans VJ, Travis WD. Immunohistochemical study of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Hum Pathol 1997;28:1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsui K, Takeda K, Yu ZX, Travis WD, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Role for activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ii M, Yamamoto H, Adachi Y, Maruyama Y, Shinomura Y. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) in human cancer invasion, apoptosis, growth, and angiogenesis. Exp Biol Med 2006;231:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy G, Cockett MI, Ward RV, Docherty AJ. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of elastin, type IV collagen and proteoglycan: A quantitative comparison of the activities of 95kDa and 72kDa gelatinases, stromelysins-1 and -2 and punctuated metalloproteinase (PUMP). Biochem J 1991;277:277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noe V, Fingleton B, Jacobs K, Crawford HC, Vermeulen S, Steelant W, Bruyneel E, Matrisian LM, Mareel M. Release of an invasion promoter E-cadherin fragment by matrilysin and stromelysin-1. J Cell Sci 2001;114:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 2006;127:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamamura Y, Otani T, Kanatani N, Koyama E, Kitagaki J, Komori T, Yamada Y, Costantini F, Wakisaka S, Pacifici M, et al. Developmental regulation of Wnt-beta-catenin signals is required for growth plate assembly, cartilage integrity, and endochondral ossification. J Biol Chem 2005;280:19185–19195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leeman MF, Curran S, Murray GI. New insights into the roles of matrix metalloproteinases in colorectal cancer development and progression. J Pathol 2003;201:528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goncharova EA, Goncharov DA, Lim PN, Noonan DJ, Krymskaya VP. Modulation of cell migration and invasiveness by tumor suppressor TSC2 in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;34:473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chun HJ, Zheng L, Ahmad M, Wang J, Speirs CK, Siegel RM, Dale JK, Puck J, Davis J, Hall CG, et al. Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature 2002;419:395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamoto K, Kuratsu J, Ozawa M. Beta-catenin cleavage in non-apoptotic cells with reduced cell adhesion activity. Int J Mol Med 2005;15:973–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozcan U, Ozcan L, Yilmaz E, Duvel K, Sahin M, Manning BD, Hotamisligil GS. Loss of the tuberous sclerosis complex tumor suppressors triggers the unfolded protein response to regulate insulin signaling and apoptosis. Mol Cell 2008;29:541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK, Yeung RS. Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic angiomyolipomas and other perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2007;38:1361–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]