Abstract

Rationale: Cross-talk between glucocorticoid receptors and histone deacetylases (HDACs) under steroid-insensitive conditions has not been explored.

Objectives: To evaluate expression and interaction of HDACs with glucocorticoid receptor isoforms in bronchoalveolar lavage and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from steroid-resistant versus steroid-sensitive patients with asthma.

Methods: Expression of HDACs 1 through 11 was measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction in primary cells and in the DO11.10 cell line, designed to overexpress glucocorticoid receptor β. Glucocorticoid receptor β expression was inhibited in bronchoalveolar lavage cells by small interfering RNA. Human HDAC2 promoter fragments were cloned into a luciferase reporter vector, and transiently transfected with glucocorticoid receptor α– and β–encoding plasmids into the cells. Luciferase activity was then assayed in response to glucocorticoids.

Measurements and Main Results: Levels of HDAC2 mRNA, but not other histone deacetylases, were significantly decreased in bronchoalveolar lavage cells but not in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from steroid-resistant patients with asthma. Overexpression of glucocorticoid receptor β in DO11.10 cells selectively reduced HDAC2 mRNA and protein levels. Silencing of glucocorticoid receptor β in bronchoalveolar lavage cells from patients with asthma significantly increased HDAC2 mRNA. Luciferase activity assays with HDAC2 promoter reporter constructs identified two glucocorticoid-inducible regions in the HDAC2 promoter. Promoter activity was increased more than fourfold in dexamethasone-treated cells cotransfected with glucocorticoid receptor α. Cotransfection of glucocorticoid receptor β abolished this effect in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusions: Glucocorticoid receptor β controls expression of histone deacetylase 2 by inhibiting glucocorticoid response elements in its promoter. This highlights a novel mechanism by which glucocorticoid receptor β promotes steroid insensitivity (Li et al.: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:S146; and Li et al.: J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:AB104).

Keywords: glucocorticoid receptor β, asthma, glucocorticoid response element, gene expression regulation

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY.

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Glucocorticoids are the major antiinflammatory drug used for the treatment of asthma. They act by engaging cellular glucocorticoid receptors to function. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are recruited by glucocorticoid receptors for transrepression. It has been noted that the non–ligand-binding isoform of the glucocorticoid receptor, glucocorticoid receptor β, might have intrinsic gene-specific transcriptional activity. Expression of this isoform is known to be increased under steroid-insensitive conditions. However, the precise role of glucocorticoid receptor β in controlling gene transcription remains uncertain. We explored the possibility of cross-talk between glucocorticoid receptor β and histone deacetylases because reduced histone deacetylase 2 has been reported to contribute to steroid resistance in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our study demonstrates the presence of functional glucocorticoid response elements in the promoter of the human HDAC2 gene and provides evidence that the glucocorticoid receptor β isoform is capable of inhibiting HDAC2 promoter activity, thus controlling cellular levels of histone deacetylase 2. This novel cross-talk mechanism provides another level of regulation for airway cellular responses to glucocorticoids.

At present, glucocorticoids (GCs) are the major antiinflammatory drugs used for the treatment of asthma and other chronic inflammatory conditions. A subset of individuals with asthma, often referred to as steroid resistant (SR), do not respond to GC therapy (1). At the molecular level, GCs interact with cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptor α (GCRα), inducing GCRα translocation to the nuclei of target cells. Activated GCRα interacts with coactivator complexes to induce histone H4 acetylation to transactivate, and engages histone deacetylases (HDACs), in particular HDAC2, to transrepress (2). There is increasing evidence to suggest that reduction of HDAC2 activity and expression may account for the amplified inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, thereby blocking steroid action (3, 4).

GCRβ, the homologous isoform of GCRα in human cells, differs from GCRα in its carboxyl terminus, where the last 50 amino acids of GCRα are replaced by a nonhomologous, 15–amino acid sequence (5). As a result of this difference, GCRβ does not bind GC or transactivate promoter regions in GC-responsive genes (6–8). GCRβ may contribute to steroid resistance by competing with GCRα for binding to the glucocorticoid response element (GRE) site or by competing for the transcriptional coactivator molecules (reviewed in References 9 and 10). GCRβ is generally viewed as transcriptionally inactive because it does not bind GC ligand. Previous studies have focused mainly on its role as a dominant negative inhibitor of GCRα (9, 10). However, two independent gene expression microarray analyses in cell lines engineered to overexpress GCRβ revealed that GCRβ regulates mRNA expression of a large number of genes negatively or positively (11, 12). GCRβ is also reported to act directly on IL-5– and IL-13–responsive promoters of GATA3 transcription factor to repress cytokine gene expression in a manner similar to GCRα (13). These data suggest that GCRβ might have intrinsic gene-specific transcriptional activity in a GCRα-independent way. However, the precise role of GCRβ in controlling gene transcription remains uncertain. Because of the overall lower expression of GCRβ expression in most cell types compared with the ligand-binding isoform GCRα, debate continues about what impact GCRβ has on cellular responses to GCs. In the current study, we explored the novel possibility of cross-talk between GCRβ and HDACs because reduced HDAC2 has been reported to contribute to steroid resistance in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3, 4).

Some of the results of these studies have been reported in the form of abstracts (14, 15).

METHODS

Subjects

We enrolled 20 nonsmoking adults (age, >18 yr) with asthma, defined by a clinical history of asthma, airflow limitation (baseline FEV1 ≤85% predicted), and either airway hyperresponsiveness (provocative concentration of methacholine causing a 20% fall in FEV1, <8 mg/ml) or bronchodilator responsiveness (>12% and 200-ml improvement in FEV1% predicted after 180 mg of metered-dose inhaler albuterol). The corticosteroid response of subjects with asthma was classified on the basis of their prebronchodilator morning FEV1% predicted response to a 1-week course of oral prednisone (40 mg/d). Subjects with asthma were defined as steroid-resistant (SR) if they had less than 10% improvement in FEV1 and as steroid-sensitive (SS) if they showed significant improvement (≥12%). Informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Jewish Health (Denver, CO). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) RNA samples from a previously characterized group of subjects with SR and SS asthma were used in this study. Information about these subjects is provided in the “Patients characteristics table” in the previous publication by our group (16). Characteristics of patients whose peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were included in this study are shown in Table E1 in the online supplement. Some patients were treated with inhaled corticosteroids at the time of the study, but inhaled corticosteroids were withheld on the day of bronchoscopy or PBMC collection. Subjects treated with oral GCs were excluded from the study.

Specimen Collection

PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation from heparinized venous blood of subjects with SR or SS asthma. Seven subjects in each group underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy with BAL according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (16). BAL cells were filtered through a 70-μm (pore size) Nylon cell strainer (Becton Dickson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ), centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 minutes, washed two times, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for GCR and HDAC mRNA

BAL cells (1 × 106) or PBMCs (1 × 106) were preserved in 350 μl of RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) immediately after isolation. Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy mini kit, transcribed into cDNA, and analyzed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using the dual-labeled fluorigenic probe method (ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detector; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described by us earlier (16). Relative gene expression levels were calculated and normalized to the corresponding levels of a housekeeping gene (18S RNA). Standard curves for all targets were generated using the fluorescence data from twofold serial dilutions of 1,000 ng of total RNA of the target sample.

Expression of GCRβ in Murine DO11.10 Hybridoma Cells

A murine DO11.10 T cell hybridoma constructed to constitutively overexpress human GCRβ/GFP as a bicistronic unit or GFP alone, as described by us earlier (17), was used in this study. HDAC1 and HDAC2 mRNA and protein levels were evaluated in GCRβ/GFP DO11.10 cells and in corresponding GFP only–expressing control DO11.10 cells by real-time PCR and Western blot.

Western Blotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared from GCRβ/GFP DO11.10 cells and corresponding GFP only–expressing control DO11.10 cells. Ten micrograms of protein per condition were run on a 4–25% gradient gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blotted with anti-HDAC1, anti-HDAC2, and anti-GCR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies. To control the quality of protein preparation, the membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) used as loading control protein. Developed X-ray films were scanned and densitometry of the bands was quantified with NIH Image software (version 1.63) (this software is available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image).

Silencing of GCR Expression with Specific Small Interfering RNA

GCRβ annealed siRNA was designed and synthesized by Applied Biosystems (Bedford, MA) as described by us earlier (16). BAL cells (5 × 106) were treated with 1 μg of GCRβ siRNA or nonsilencing control siRNA in a Nucleofector device, using a Nucleofector human monocytes kit (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). The cells were cultured for 48 hours and harvested for RNA isolation or fixed on slides. GCRβ knockdown was ascertained by real-time PCR and immunostaining. The effect of the GCRβ silencing on HDAC1 and HDAC2 gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR.

Plasmids

pEGFP-hGCRβ and pEGFP-hGCRα plasmids, which carry the full-length coding region of human GCRβ (hGCRβ) and hGCRα under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter, were used in this study. Plasmid pEGFP-hGCRβ was previously described (17) and plasmid pEGFP-hGCRα was made by replacing the BamHI–XbaI fragment of hGCRβ with the BamHI–KpnI fragment of hGCRα. A series of luciferase reporter constructs was generated by cloning promoter fragments of the human HDAC2 promoter into the pGL3-basic vector. pRSV-β-galactosidase and pGL3-basic vector were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Cell Transfection and Luciferase Assay

Human A549 alveolar epithelial cells were cultured in minimal essential medium and transfected with Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 293-GJ cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (18). Semiconfluent cells in 24-well plates were transiently transfected with human HDAC2 promoter reporter constructs ± hGCRα and various amounts of hGCRβ plasmids. pGL3-basic plasmid was added to ensure that each transfection condition received the same amount of total DNA. To normalize for transfection efficiency, 50 ng of pRSV-β-galactosidase was added to each transfection. Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were incubated for 24 hours ± 10 nM dexamethasone (DEX). Luciferase reporter assays were performed with a luciferase assay kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. β-Galactosidase activity was measured with a Galacto-Light chemiluminescence kit (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Real-time PCR data and luciferase activation between selected cell transfection groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student t test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

BAL Macrophages of SR Patients with Asthma Have Decreased HDAC2 mRNA Expression

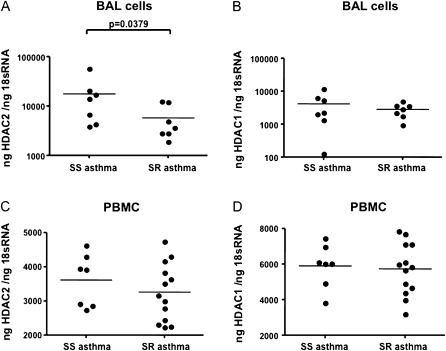

Expression of GCRα, GCRβ, HDAC1, and HDAC2 was detected in BAL cells of SR and SS subjects with asthma. Analysis was restricted to mRNA quantification because of the limited number of cells available. No difference in cellular content between BAL samples from SR and SS patients was observed in our study. Ninety percent macrophages, about 5% lymphocytes, 0–2% eosinophils, and 0–2% neutrophils were present in BAL samples from both SS and SR asthma groups. Real-time PCR results showed that there was a significant decrease in HDAC2 mRNA expression in the BAL cells of SR subjects with asthma as compared with SS subjects with asthma (17,735 ± 7,049 vs. 5,799 ± 1,699 ng of HDAC2/ng of 18S RNA, n = 7; P = 0.0379) (Figure 1A). There was no significant difference in HDAC1 mRNA expression by BAL cells from the two asthma groups (4,170 ± 1,522 vs. 2,848 ± 507 ng of HDAC1/ng of 18S RNA, n = 7) (Figure 1B). We had previously analyzed GCRα and GCRβ expression in these samples and reported a significant increase in GCRβ mRNA expression in SR asthma BAL samples as compared with SS asthma BAL samples, whereas no difference in GCRα mRNA expression was observed between the two groups. Data about the expression of GCRα and GCRβ in these samples have been published (16). No difference in the expression of HDAC3 through HDAC11 mRNAs was detected in these samples (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Changes in histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) mRNA expression in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells but not peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from subjects with steroid-resistant (SR) asthma. (A) HDAC2 gene expression but not (B) HDAC1 gene expression is significantly decreased in BAL macrophages of subjects with SR asthma as compared with subjects with steroid-sensitive (SS) asthma. No difference in (C) HDAC2 and (D) HDAC1 mRNA expression exists in PBMCs of subjects with SS and SR asthma, as shown by real-time polymerase chain reaction.

To determine whether the differences in the level of HDAC2 expression in SR versus SS subjects with asthma occur in peripheral blood cells as well, we measured the levels of HDAC mRNA in PBMCs of 13 SR subjects with asthma and 7 SS subjects with asthma by real-time PCR. No difference in HDAC2 and HDAC1 mRNA expression in PBMCs from SR versus SS subjects was detected (Figures 1C and 1D). There was also no significant difference in GCRα mRNA expression in the PBMCs of SR subjects as compared with SS subjects with asthma (41.85 ± 7.89 vs. 49.25 ± 10.15 ng of GCRα/ng of 18S RNA; P = 0.30), or in GCRβ mRNA expression as well (3.20 ± 0.23 vs.3.17 ± 0.17 fg of GCRβ/ng of 18S RNA; P = 0.47).

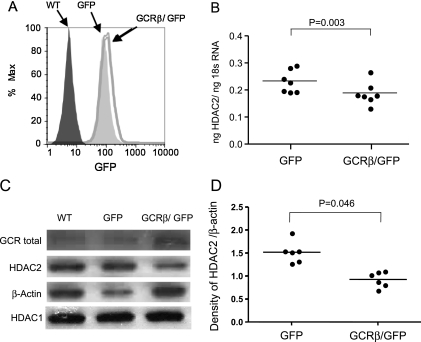

Overexpression of GCRβ in DO11.10 T Cell Hybridoma Reduces the Level of HDAC2

To determine whether the increased level of GCRβ interfered with HDAC2 gene expression, we compared HDAC1 and HDAC2 mRNA and protein levels in murine DO11.10 T cell hybridoma cells that expressed different levels of human GCRβ (17). There was a significant reduction in HDAC2 mRNA expression in GCRβ/GFP transgenic cells compared with the cells that expressed GFP only (ng of HDAC2/ng of 18S RNA: 0.19 ± 0.02 vs. 0.24 ± 0.02 for GCRβ/GFP vs. GFP only–expressing cells, respectively) (Figure 2B), whereas no difference in HDAC1 mRNA expression was observed (ng of HDAC1/ng of 18S RNA: 0.72 ± 0.07 vs. 0.69 ± 0.07) for GCRβ/GFP versus GFP only–expressing cells, respectively. A significant reduction in HDAC2 protein expression was confirmed by Western blot in cell lysates of GCRβ/GFP-expressing DO11.10 cells (Figures 2C and 2D) as compared with GFP only–expressing cells. In contrast, no changes in HDAC1 protein expression were found (Figure 2C). Total GCR determination was used to monitor the effect of gene transfection, and protein loading was normalized by β-actin content (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of glucocorticoid receptor β (GCRβ) overexpression on histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) expression by DO11.10 cells. (A) Distribution of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in GFP/GCRβ and GFP-only retrovirally transduced DO11.10 cells. The level of GFP expression in transgenic DO11.10 cells corresponds to GCRβ expression. (B) Reduced HDAC2 mRNA and (C and D) protein expression in GCRβ-overexpressing cells. HDAC2 gene expression was evaluated by real-time polymerase chain reaction in DO11.10 cells expressing GFP/GCRβ versus DO11.10 cells expressing GFP only (n = 7). HDAC2 protein expression was detected in wild-type (WT), GFP/GCRβ, and GFP DO11.10 cells by Western blot. (C) A representative Western blot experiment and (D) densitometry data are shown (of six independent experiments performed).

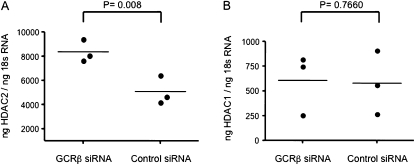

Effect of GCR Gene Silencing on HDAC2 Expression in BAL Cells from Patients with Asthma

To provide more definitive evidence regarding the regulatory influence of GCRβ on HDAC2, we silenced GCRβ gene expression in primary BAL cells of SR subjects with asthma and examined the resultant HDAC2 gene expression in these cells. Freshly isolated BAL macrophages from SR patients with asthma were transfected by electroporation with GCRβ siRNA or nonsilencing control siRNA. As published by us earlier (16), real-time PCR and microscopy results indicated that introduction of GCRβ siRNA 48 hours after transfection specifically inhibited GCRβ expression in the BAL cells. In this study, the effects of GCRβ silencing on HDAC2 expression were analyzed in the same BAL RNA samples. In these samples, silencing of GCRβ resulted in a significant increase in HDAC2 gene expression (ng of HDAC2/ng of 18S RNA: 8,367 ± 308, n = 3; P = 0.008) compared with the nonsilencing siRNA (5,092 ± 393 ng of HDAC2/ng of 18S RNA) (Figure 3A). As well, no change in HDAC1 gene expression was observed in GCRβ-silenced BAL cells compared with nonsilencing control siRNA group (ng of HDAC1/ng of 18S RNA: 607 ± 102 vs. 579 ± 107, n = 3) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor β (GCRβ) gene expression by use of specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) enhances histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) expression. Introduction of GCRβ siRNA into human bronchoalveolar lavage cells increases (A) HDAC2 gene expression as compared with the nonspecific siRNA control group, whereas (B) no effect on HDAC1 gene expression was observed.

These data suggest that inhibition of the HDAC2 gene in BAL macrophages can occur as a consequence of the increased expression of GCRβ in BAL macrophages of SR subjects with asthma. Importantly, GCRβ can regulate HDAC2 function in primary cells.

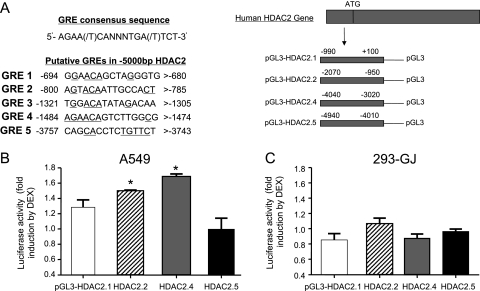

Identification of Functional GREs in Human HDAC2 Gene Promoter

Sequence analysis of the human HDAC2 promoter revealed several potential GCR-binding sites within the putative GRE (http://promoter.colorado.edu/geneact/potentialBS.html). The location of these sites is as follows: bp −1454 to −1447, −1572 to −1565, −2667 to −2660, and –3832 to −3825 relative to the transcriptional start site (TSS). To functionally determine whether the human HDAC2 promoter is regulated by GCR, we constructed a series of human HDAC2 promoter reporter constructs by cloning 5 kb of the HDAC2 promoter region containing these genomic fragments into the reporter vector (Figure 4A). The pLG3-HDAC2.5 construct does not contain a putative GRE, and therefore it was used as a negative control in this study. These reporter plasmids were transfected into A549 cells, and relative luciferase activity was determined after incubation of the transfected cells with or without 10 nM DEX for 24 hours. As seen in Figure 4B, DEX treatment of A549 cells transfected with pLG3-HDAC2.1, pLG3-HDAC2.2, pLG3-HDAC2.4, and pLG3-HDAC2.5 constructs stimulated luciferase activity 1.29 ± 0.08-, 1.50 ± 0.01-, 1.67 ± 0.05-, and 1.00 ± 0.14-fold, respectively. Maximal stimulation of luciferase activity by DEX was observed with both pLG3-HDAC2.2 and pLG3-HDAC2.4 constructs, which suggests that DEX-inducible regions exist in the human HDAC2 promoter, located at bp −2070 to −950 and −4030 to −3020 relative to the TSS.

Figure 4.

Identification of a functional glucocorticoid response element (GRE) in the human histone deacetylase 2 gene (HDAC2) promoter. (A) Sequences of putative GRE-binding elements within the –5000 bp HDAC2 promoter fragments. Underlined base pairs indicate the conserved GRE sequence. The promoter regions of the HDAC2 gene, encompassing bp −990 to 100, −2070 to −950, −1970 to 3050, −4030 to −3020, and –4010 to −4940 relative to the transcriptional start site (TSS), were fused upstream of the luciferase (Luc) reporter gene to generate four pLG3-HDAC2 constructs, which are designated as pGL3-HDAC2.1 (GRE 1 and 2), HDAC2.2 (GRE 3 and 4), HDAC2.4 (GRE 5), and HDAC2.5 (no GRE). (B) A549 cells and (C) 293-GJ cells were transfected with 250 ng of the four pGL3-HDAC2 promoter reporter plasmids, respectively, along with 50 ng of pRSV-β-galactosidase to monitor transfection efficiency. Cells were incubated for 24 hours ± 10 nM dexamethasone (DEX) before luciferase activity measurements. Luc activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activities, and the data are presented as the fold induction of luciferase activity by DEX. Data represent means ± SD obtained from four independent experiments. *Promoter constructs selected for further functional experiments as DEX inducible (P < 0.05).

Effects of Intrinsic GCRβ Expression on GRE in HDAC2 Promoter

Unlike A549 cells, transfection of 293-GJ cells with pLG3-HDAC2 reporter plasmids alone did not increase luciferase activity in response to DEX (Figure 4C). We hypothesized that differences in endogenous expression of GCRα and GCRβ isoforms in A549 and 293-GJ cell lines are responsible for the differential regulation of HDAC2 promoter constructs in these cell lines. Therefore, we measured the expression of GCRα and GCRβ mRNAs in A549 and 293-GJ cells by real-time PCR. Levels of GCRα mRNA were found to be significantly higher in A549 cells as compared with 293-GJ cells (0.077 ± 0.008 vs. 0.024 ± 0.001 pg/ml, n = 4; P = 0.0006), despite similar levels of GCRβ mRNA in these two cell lines (1.064 ± 0.061 vs. 0.873 ± 0.046 fg/ml, n = 4). This indicates that there was a significantly higher GCRα-to-GCRβ molar ratio in A549 cells compared with 293-GJ cells: GCRα/GCRβ was 7,282 ± 754 in A549 cells versus 2,776 ± 193 in 293-GJ cells (n = 4; P = 0.0012).

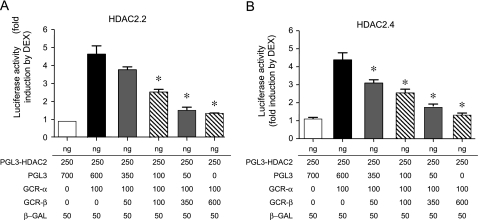

Repression GRE Activity in Human HDAC2 Promoter by GCRβ

When 293-GJ cells were transfected with 100 ng of GCRα, luciferase activity of the HDAC2 promoter constructs was increased more than fourfold on stimulation with 10 nM DEX (5.11 ± 0.52-fold when transfected with HDAC2.2 and 4.03 ± 0.15-fold when transfected with HDAC2.4 promoter reporter plasmids). When coexpressed with GCRα, however, GCRβ inhibited transcription in a dose-dependent manner, with 3.5-fold overexpression of GCRβ relative to GCRα, leading to more than 50% reduction of luciferase activity (Figure 5). Taken together, these results suggest that GCRβ represses the DEX-induced human HDAC2 gene promoter GRE activity and may control HDAC2 expression by the cells.

Figure 5.

Glucocorticoid receptor β (GCRβ)–mediated inhibition of dexamethasone (DEX)-inducible glucocorticoid response element activity in the histone deacetylase 2 gene (HDAC2) promoter. 293-GJ cells were transfected with 250 ng of (A) HDAC2.2 or (B) HDAC2.4 promoter reporter plasmids either alone or with 100 ng of GCRα and various amounts of GCRβ-encoding plasmids. pGL3-basic plasmid cotransfections were used to adjust the total amount of DNA to 1 μg. Luciferase activities were determined in cell lysates as described in Figure 4. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the reported values denote means ± SD derived from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 as compared with GCRα-transfected cells. β-GAL = β-galactosidase.

DISCUSSION

The current study assessed the expression of HDACs in BAL cells and PBMCs from patients with SR asthma as compared with SS asthma. Our results show a significant selective decrease in HDAC2 mRNA expression in the BAL of SR subjects compared with SS subjects with asthma, out of HDAC1 through HDAC11 tested. In this article, by using GCRβ silencing and gene overexpression models we provide evidence of GCRβ interference with HDAC2 expression in asthmatic BAL cells. Several functional GREs were identified in the human HDAC2 promoter. In the current article, we also demonstrate the repression of HDAC GREs by elevated GCRβ.

Eighteen HDACs have been recognized in mammalian cells (19, 20) and are now classified into four major classes in which each member targets different patterns of acetylation and therefore regulates different type of genes. At the time of this study, primers for only 11 human HDACs were available, and hence the expression of HDAC1 through HDAC11 was analyzed by real-time PCR in human BAL cells. Among them, HDAC1 and HDAC2 are key enzymes modifying the expression of inflammatory genes in airway diseases. Both HDACs belong to human class I and are enzymatic transcriptional corepressors homologous to yeast Rpd3. They are localized mainly to the nucleus and are recruited to promoters by DNA-binding proteins and mediate transcriptional repression. In bronchial biopsies, alveolar macrophages and PBMCs from subjects with asthma, a reduction in HDAC activity and/or expression compared with normal subjects has been reported, thus favoring increased inflammatory gene expression (21). However, there have been some inconsistent reports concerning the expression and activity of which HDAC is affected in asthma. It has been observed that HDAC2 expression and activity are reduced in subjects with severe asthma and smoking subjects with asthma, as well as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4, 22). However, another study reported a small reduction in the expression of HDAC1, but no change in HDAC2 expression, in bronchial biopsies and alveolar macrophages obtained from patients with asthma (22).

In our study, selective inhibition of HDAC2 mRNA expression in BAL macrophages from SR patients with asthma, as compared with SS patients with asthma, was observed. However, no difference in HDAC mRNA expression was noted in PBMCs between these two groups of patients. In these samples, we previously reported an increased level of GCRβ in BAL cells, whereas no difference in GCRβ expression was observed in PBMCs from SR subjects with asthma as compared with SS subjects with asthma (16). We demonstrated that human monocytes express significantly higher levels of GCRβ as compared with lymphocytes (23). Therefore it is possible that selective inhibition of HDAC2 expression is cell type specific and was seen only in BAL samples (these samples according to cell differentials contain more than 90% macrophages) because of the higher levels of GCRβ expression by these cells. In addition, it is known that the lung inflammatory milieu in SR asthma is increased and that inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α can enhance macrophage expression of GCRβ (16, 24).

In the current study, we therefore examined how differential expression of GCRβ by the cells affects HDAC2 expression. We found that overexpression of GCRβ inhibited HDAC2 mRNA and protein expression in GCRβ transgenic DO11.10 cells; GCRβ silencing in the BAL of SR subjects with asthma increased HDAC2 mRNA expression. These data suggest that inhibition of HDAC2 expression by GCRβ is a previously unidentified pathway that promotes impaired response to glucocorticoids in cells with elevated GCRβ expression.

HDAC2 is recruited to the activated GCR transcriptional complex to facilitate GCR-mediated transrepression via histone deacetylation. On the other hand, GCR has been reported to be a nonhistone protein substrate for HDAC2: after ligand binding GCRα is acetylated and HDAC2-mediated GCR deacetylation is required to allow GCR interaction with NF-κB to transrepress (3). In this article, we report a novel level of GCR-HDAC2 cross-talk. We demonstrate for the first time the presence of functional GREs in the human HDAC2 gene promoter. Interestingly, we found that endogenous GCR expression already has an impact on HDAC2 expression by the cells. In this study, we noted differential response to DEX in A549 and 293-GJ cell lines transfected with luciferase reporter HDAC2 promoter constructs with potential GRE sites. No induction of luciferase activity from these promoter constructs occurred in the 293-GJ cell line as compared with A549 cells. The 293-GJ cell line had significantly lower GCRα mRNA expression compared with the A549 cell line, but comparable levels of GCRβ mRNA; and therefore a significantly lower GCRα-to-GCRβ ratio. Overexpression of GCRα in the 293-GJ cell line resulted in significant potentiation of HDAC2 promoter activity in the presence of DEX. GCRβ coexpression dose dependently abolished DEX-induced luciferase activity from transfected HDAC2 promoter constructs.

In summary, our article demonstrates the presence of a functional GRE in the promoter of the human HDAC2 gene and provides evidence that an alternatively spliced GCR isoform, GCRβ, levels of which have been reported to be increased in SR asthma and other inflammatory lung conditions, is capable of inhibiting HDAC2 GRE activity. This novel cross-talk mechanism provides another level of regulation for airway cellular responses to glucocorticoids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maureen Sandoval for help in preparing this manuscript. The authors also thank Dr. Liangguo Xu (Department of Immunology, National Jewish Health) for technical support in the molecular biology experiments.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI070140 and HL37260. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0015OC on June 10, 2010

Author Disclosure: L-b.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. D.Y.M.L. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. R.J.M. served as a consultant for Schering 2007–2009, AstraZeneca 2009, and Genentech/Novartis 2007–2009 ($5,001–$10,000). He served on the Board or Advisory Board and received lecture fees from Teva 2008 ($5,001–$10,000). E.G. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hamid QA, Wenzel SE, Hauk PJ, Tsicopoulos A, Wallaert B, Lafitte JJ, Chrousos GP, Szefler SJ, Leung DY. Increased glucocorticoid receptor β in airway cells of glucocorticoid-insensitive asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1600–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adcock IM, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Glucocorticoids: effects on gene transcription. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2004;1:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito K, Yamamura S, Essilfie-Quaye S, Cosio B, Ito M, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Histone deacetylase 2–mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-κB suppression. J Exp Med 2006;203:7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito K, Ito M, Elliott WM, Cosio B, Caramori G, Kon OM, Barczyk A, Hayashi S, Adcock IM, Hogg JC, et al. Decreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Encio IJ, Detera-Wadleigh SD. The genomic structure of the human glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 1991;266:7182–7188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamberger CM, Bamberger AM, de Castro M, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor β, a potential endogenous inhibitor of glucocorticoid action in humans. J Clin Invest 1995;95:2435–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oakley RH, Jewell CM, Yudt MR, Bofetiado DM, Cidlowski JA. The dominant negative activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform: specificity and mechanisms of action. J Biol Chem 1999;274:27857–27866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakley RH, Sar M, Cidlowski JA. The human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform: expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J Biol Chem 1996;271:9550–9559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross KL, Lu NZ, Cidlowski JA. Molecular mechanisms regulating glucocorticoid sensitivity and resistance. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009;300:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kino T, Su YA, Chrousos GP. Human glucocorticoid receptor isoform β: recent understanding of its potential implications in physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009;66:3435–3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis-Tuffin LJ, Jewell CM, Bienstock RJ, Collins JB, Cidlowski JA. Human glucocorticoid receptor β binds RU-486 and is transcriptionally active. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27:2266–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kino T, Manoli I, Kelkar S, Wang Y, Su YA, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) β has intrinsic, GRα-independent transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;381:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly A, Bowen H, Jee YK, Mahfiche N, Soh C, Lee T, Hawrylowicz C, Lavender P. The glucocorticoid receptor β isoform can mediate transcriptional repression by recruiting histone deacetylases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:203–208; e201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Leung DYM, Goleva E. Glucocorticoid receptor β (GCR)-β regulates HDAC2 expression in bronchoalveolar lavage cells (BAL) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of asthmatics [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:S146. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Leung DYM, Goleva E. Repreression of glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) transactivation and glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) activities within human HDAC2 gene promoter by GCR-β [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:AB104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goleva E, Li LB, Eves PT, Strand MJ, Martin RJ, Leung DY. Increased glucocorticoid receptor β alters steroid response in glucocorticoid-insensitive asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauk PJ, Goleva E, Strickland I, Vottero A, Chrousos GP, Kisich KO, Leung DY. Increased glucocorticoid receptor β expression converts mouse hybridoma cells to a corticosteroid-insensitive phenotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu LG, Li LY, Shu HB. TRAF7 potentiates MEKK3-induced AP1 and CHOP activation and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2004;279:17278–17282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J 2003;370:737–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, Ponte JF. Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;983:84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Caramori G, Lim S, Oates T, Chung KF, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Expression and activity of histone deacetylases in human asthmatic airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cosio BG, Mann B, Ito K, Jazrawi E, Barnes PJ, Chung KF, Adcock IM. Histone acetylase and deacetylase activity in alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li LB, Leung DY, Hall CF, Goleva E. Divergent expression and function of glucocorticoid receptor β in human monocytes and T cells. J Leukoc Biol 2006;79:818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goleva E, Hauk PJ, Hall CF, Liu AH, Riches DW, Martin RJ, Leung DY. Corticosteroid-resistant asthma is associated with classical antimicrobial activation of airway macrophages. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.