Abstract

Curve estimation techniques were used to identify the pattern of therapeutic change in female rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Within-session data on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale were obtained, in alternate therapy sessions, on 171 women. The final sample of treatment completers included 54 prolonged exposure (PE) and 54 cognitive-processing therapy (CPT) completers. For both PE and CPT, a quadratic function provided the best fit for the total PTSD, reexperiencing, and arousal scores. However, a difference in the line of best fit was observed for the avoidance symptoms. Although a quadratic function still provided a better fit for the PE avoidance, a linear function was more parsimonious in explaining the CPT avoidance variance. Implications of the findings are discussed.

The purpose of controlled therapy outcome research is to identify specific cause-and-effect relationships that increase knowledge of mechanisms of change for affecting psychopathology and, consequently, allow for the development of increasingly effective psychotherapies (Borkovec & Miranda, 1999). Although comparisons of treatment with no-treatment conditions allow one to rule out the role of history, maturation, repeated testing, and statistical regression as explanatory factors for differences in treatment outcome, comparisons of treatment with placebo or a minimal-attention group allow one to conclude that something specific to the treatment condition, above and beyond the general therapeutic relationship, is responsible for therapeutic change (Borkovec & Castonguay, 1998).

Once the efficacy of a new therapy is established in the initial stages through controlled trials, comparative designs are generally used to determine whether the therapy is superior to another treatment or matches the outcome of an already established treatment with adequate statistical power. Although comparative designs are useful for demonstrating empirical support for a new therapy, these designs are confounded by the fact that the two compared therapies are inherently different in a large number of ways. However, the results of comparative studies are useful in that they can help both of the treatments in question evolve and change on the basis of new clinical and empirical knowledge that is obtained over the course of the clinical trial (Devilly & Foa, 2001; Tarrier, 2001).

Treatment-outcome research with female rape victims has largely involved the use of controlled and comparative trials. Two of the more researched treatments used with this population are prolonged exposure therapy (PE; Foa et al., 1999; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991) and cognitive-processing therapy (CPT; Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993). Clinical trials conducted with these therapies established the initial efficacy for both these treatments (Foa et al., 1991, 1999; Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993). More recently, Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, and Feuer (2002) conducted a clinical trial comparing PE and CPT with a minimal-attention (MA) control group. Although both therapies proved to be superior to the MA group, there were no differences between PE and CPT on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom outcome measures.

The purpose of these analyses was to extend the findings of Resick et al. (2002) by (a) examining within-therapy patterns of change in PTSD symptoms in female rape victims treated with either PE or CPT and (b) examining symptom clusters of PTSD to determine whether different types of symptoms improve differentially across the two treatments. Curve estimation techniques were used to determine the lines of best fit for the PTSD symptom scores obtained across sessions for both PE and CPT. We subsequently used these lines to generate mathematical functions that could have predictive value in plotting the course of therapeutic progress for this population.

Method

Participants

An intent-to-treat sample was composed of 171 female rape victims (for a detailed description of the sample please refer to Resick et al., 2002). At pretreatment, all of the women met criteria for PTSD. Of the 171 women who were randomized into treatment, 13 never initiated therapy. Of the remaining 158 women who initiated therapy, 37 dropped out of treatment, and the remaining 121 women completed their treatment condition as well as the posttreatment assessment: 40 were assigned to PE, 41 were assigned to CPT, and 40 were assigned to a 6-week MA control group.

There were no significant differences between the groups in the intent-to-treat sample. Overall, the women were an average of 32 years of age (SD = 9.9) and had 14.3 years of education (SD = 2.6). The majority of the women were never married, divorced, or separated (76%). The sample was 71% White, 25% African American, and 4% Other. The average length of time since the women’s rape was 8.5 years (SD = 8.5 years). The range was from 3 months to 33 years.

The 40 women who were assigned to the MA condition were still PTSD positive at the completion of the 6-week waiting period. Subsequent to the completion of the MA condition, they were randomly assigned to either PE or CPT. Fourteen of these 40 women finished the PE protocol, and 13 of them finished the CPT protocol. The remaining 13 MA completers either did not initiate therapy or dropped out of the therapy condition to which they were subsequently assigned. Thus the final treatment completer sample was composed of 54 women who completed PE and 54 women who completed CPT.

There were no significant differences between the groups in the treatment completer group. The women were an average of 33 years of age (SD = 10.2) and had 14.8 years of education (SD = 2.4). The majority of the women were never married, divorced, or separated (71%). The sample was 83% White, 15% African American, and 2% Other. The average length of time since the women’s rape was 9.4 years (SD = 8.6 years). The range was 3 months to 33 years.

Measures

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

The CAPS (Blake et al., 1990) is a 30-item structured diagnostic interview that contains separate 5-point frequency and intensity rating scales (0–4) for symptoms identified with PTSD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., rev.; DSM–III–R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Interrater reliability for each of the three main subscales (Intrusion, Avoidance, and Arousal), on both frequency and severity ratings, is reported to be better than .92, and high convergent validity has been reported with other PTSD measures. The scales were rescored to reflect PTSD diagnoses that were based on the DSM–IV (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria.

PTSD Symptom Scale (PSS)

The PSS (Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993) consists of 17 self-report items that correspond to the symptoms of the DSM–III–R diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Each symptom is rated for frequency on a 4-point scale (total range 0–51), which can be summed to derive a total score. A score of 10 or less is considered mild or no PTSD; scores between 11 and 27 are indicative of moderate PTSD; scores of 28 or greater indicate severe PTSD. High interrater reliability (κ =.90) has been reported for the PSS (Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992). We rescored the scale to reflect DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for the PTSD symptom clusters.

Procedure

The women who were assigned to the PE therapy condition received nine biweekly sessions of therapy over a 4.5-week period. The PE manual (Foa, Hearst, Dancu, Hembree, & Jaycox, 1994) was similar to the protocol later published by Foa and Rothbaum (1997). The first session was 1 hr and the remaining eight sessions were 1.5 hr long, thus providing 13 hr total of therapy. The first session was an orientation session in which the women were taught about symptoms of PTSD and given the theoretical rationale for PE. They were then trained in the coping technique of controlled breathing for the management of anxiety symptoms. In the second session, the women were taught about the common reactions to assault. Following this, the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS; Foa et al., 1994) was introduced to generate a hierarchy for in vivo exposures. This hierarchy included shopping malls, parks, ATM machines, and a variety of other places that might have been implicated in the trauma situation. The in vivo exposure situations were subsequently assigned for homework.

Starting with Session 3, the women assigned to PE were instructed to do imaginal exposures to the traumatic memory of the rape in each of the remaining seven sessions. The sessions started with a 15-min discussion of homework followed by the imaginal exposure, which was conducted over a 45- to 60-min period of the session. SUDS ratings were obtained during the imaginal exposures to gauge the degree of within-session habituation. After the material from the imaginal exposure was processed, the remainder of the session was used to assign homework. The homework typically comprised practicing controlled breathing, listening once to the audiotape of the entire session, listening daily to the taped imaginal exposure from the session, and conducting daily in vivo exposure exercises. The in vivo exposures consisted of exposures to trauma-relevant cues for a minimum duration of 45 min. The women were encouraged to record their SUDS ratings (preexposure, peak, and postexposure) for both the imaginal and the in vivo exposure homework to gauge the extent of between-session habituation. Further, the women were asked to rate the frequency of their PTSD symptoms at the beginning of every-other therapy session. The PSS data were thus available for the baseline pretreatment assessment and for therapy Sessions 2, 4, 6, and 8. For the 14 women who completed PE subsequent to completing the MA condition, the post-MA PSS scores were used as baseline pretreatment scores.

The women who were assigned to CPT received 12 biweekly sessions of therapy over a 6-week period. All sessions except Sessions 4 and 5 were 1 hr in length. Sessions 4 and 5 were 1.5 hr in length, thus providing 13 hr total of therapy. The first session was an orientation session in which the women were taught about symptoms of PTSD and given the theoretical rationale for CPT. For homework, the women were asked to write an impact statement on what it meant to them that they had been raped. The meaning of the event was discussed in the second session and, by the third session, the women were asked to start identifying problematic beliefs related to the rape.

Sessions 4 and 5 were exposure sessions in which the women were asked to write a complete account of the rape that included all the sensory details. The accounts were used for expression of affect and to identify rape-related stuck points that the women were endorsing in the areas of safety, trust, control, esteem, and intimacy. Sessions 6 and 7 introduced challenging questions and faulty-thinking patterns sheets to the women that were then used to challenge the rape-related stuck points in Sessions 8 through 12. For homework, the women were given challenging beliefs worksheets to target and dismantle the rape-related stuck points specific to areas of safety, trust, control, esteem, and intimacy. As in PE, the women were asked to rate the frequency of their PTSD symptoms at the beginning of every other therapy session. The PSS data were thus available for the baseline pretreatment assessment and for therapy Sessions 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. For the 13 women who completed CPT subsequent to completing the MA condition, the post-MA PSS scores were used as baseline pretreatment scores.

Results

First, all of the participants who were accepted and randomized into the trial were analyzed. These intent-to-treat data allow a more complete picture of the results regardless of whether the women completed the treatment or even began treatment. Next, those women who completed treatment were analyzed separately to examine the efficacy of these treatments when completed in their entirety.

Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted on 171 participants, including 13 women who had been accepted into the study but never attended a therapy session. The pretreatment PSS scores of these 13 women were carried forward across all data points. For the 37 women who were therapy dropouts, the last available PSS score was carried forward for the remainder of the missing data points. The same principle was used for the 13 women who either completed the MA condition but never initiated subsequent therapy or completed the MA condition but dropped out of subsequent therapy. Thus, the technique of last observation carried forward was used to complete the PSS data for the 63 dropouts (PE: n = 34; CPT: n = 29) to allow for intent-to-treat analyses.

Secondary analyses were conducted with therapy completers only (PE: n = 54; CPT: n = 54). Multivariate analyses comparing pretreatment scores on the three PTSD clusters of reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal for PE and CPT were not significant for either the intent-to-treat sample or the therapy completer sample. This finding demonstrates that the two groups were comparable on PTSD symptoms and that there were no selection biases at pretreatment.

In the next step, mean symptom cluster and total scores on the PSS were computed for each assessment point for both PE and CPT. To make the data points for both PE and CPT roughly comparable with each other in amount of time spent in therapy sessions, we used curve estimation techniques to plot the line of best fit for the mean PSS scores of pretreatment and Sessions 2, 4, 6, and 8 for PE and for the mean PSS scores of pretreatment and Sessions 2, 4, 6, and 10 for CPT. The PSS scores for PE thus corresponded with 0.0 hr, 2.5 hr, 5.5 hr, 8.5 hr, and 11.5 hr of therapy. Similarly, the PSS scores for CPT corresponded with 0.0 hr, 2.0 hr, 4.5 hr, 8.0 hr, and 11.0 hr of therapy. (See Table 1 for a comparison of the mean PTSD symptom cluster and mean total scores for PE and CPT for both the intent-to-treat sample and the therapy completer samples.)

Table 1.

Intent-to-Treat and Therapy Completer Samples: Mean and Standard Deviation PSS Symptom Cluster and Total Scores for Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive-Processing Therapy at Each Assessment Point

| Reexperiencing | Avoidance | Arousal | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Prolonged exposure | ||||||||

| 1. Intent-to-treat | 6.62 | 3.31 | 12.35 | 4.32 | 10.06 | 3.44 | 29.03 | 9.12 |

| 1. Completer | 6.35 | 2.86 | 12.89 | 4.47 | 10.07 | 3.50 | 29.32 | 8.76 |

| 2. Intent-to-treat | 6.78 | 3.26 | 12.31 | 4.52 | 9.56 | 3.34 | 28.62 | 9.47 |

| 2. Completer | 6.91 | 2.88 | 12.94 | 4.29 | 9.94 | 3.06 | 29.76 | 8.50 |

| 3. Intent-to-treat | 7.27 | 4.21 | 11.33 | 5.03 | 9.48 | 4.16 | 28.08 | 11.39 |

| 3. Completer | 7.70 | 4.13 | 11.79 | 4.91 | 9.74 | 4.21 | 29.23 | 11.16 |

| 4. Intent-to-treat | 5.54 | 3.90 | 8.71 | 5.08 | 7.70 | 3.74 | 21.95 | 11.09 |

| 4. Completer | 5.47 | 3.82 | 8.62 | 5.09 | 7.51 | 3.75 | 21.60 | 11.29 |

| 5. Intent-to-treat | 3.45 | 3.28 | 6.06 | 4.40 | 5.36 | 3.70 | 14.87 | 9.85 |

| 5. Completer | 3.42 | 3.30 | 6.13 | 4.41 | 5.36 | 3.74 | 14.92 | 9.94 |

| Cognitive-processing therapy | ||||||||

| 1. Intent-to-treat | 6.69 | 3.09 | 12.73 | 4.57 | 10.07 | 2.77 | 29.50 | 8.29 |

| 1. Completer | 6.63 | 3.27 | 12.84 | 4.67 | 10.02 | 2.87 | 29.48 | 8.51 |

| 2. Intent-to-treat | 6.67 | 3.22 | 11.46 | 4.30 | 9.69 | 2.93 | 27.85 | 8.20 |

| 2. Completer | 6.54 | 3.24 | 11.13 | 4.28 | 9.78 | 3.06 | 27.47 | 8.37 |

| 3. Intent-to-treat | 7.21 | 3.47 | 10.83 | 4.76 | 9.03 | 3.40 | 26.88 | 9.27 |

| 3. Completer | 7.13 | 3.43 | 10.66 | 4.75 | 9.26 | 3.39 | 26.85 | 9.49 |

| 4. Intent-to-treat | 5.50 | 3.77 | 8.37 | 4.93 | 7.38 | 3.35 | 21.12 | 10.45 |

| 4. Completer | 5.46 | 3.78 | 8.34 | 4.98 | 7.44 | 3.33 | 21.11 | 10.56 |

| 5. Intent-to-treat | 2.75 | 2.86 | 5.53 | 4.20 | 5.05 | 3.62 | 13.33 | 9.26 |

| 5. Completer | 2.76 | 2.89 | 5.52 | 4.24 | 5.11 | 3.63 | 13.39 | 4.95 |

Note. PSS = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale.

A visual inspection of the PSS symptom cluster and total scores revealed that the data were largely following a curvilinear pattern. Therefore, the PSS scores for both PE and CPT were fit to both a quadratic and the more parsimonious linear function to determine which line provided the best fit for the data. The magnitude of R2 explained and the significance of the coefficients were used as criteria to determine the superiority of one fit over the other. The more complicated quadratic function was chosen over the more parsimonious linear function only if the increase in the R2 explained provided by the quadratic function was fairly large and the quadratic coefficient was significant (Norusis, 1994). Results with both the intent-to-treat sample and the therapy completer samples showed that a quadratic function provided the best fit for all three symptom clusters of PTSD in the PE therapy condition. However, although a quadratic function provided the best fit for reexperiencing, and for arousal symptom clusters for CPT, a linear function with a negative slope provided the best fit for the avoidance symptom cluster. A quadratic function also provided the best fit for the total PSS scores for both PE and CPT. Tables 2 and 3 show a comparison of the explained variances with a linear and a quadratic fit for the three mean PTSD symptom cluster scores and the mean total PSS scores for PE and CPT for both the intent-to-treat sample and the therapy completer samples. The F tests reflected in the tables were conducted to test the null hypothesis that all the coefficients in the model are 0. The individual t tests were conducted to test the significance of each individual coefficient. Both the magnitude of R2 explained and the coefficients were used as criteria to determine the line of best fit for the different PTSD symptom clusters.

Table 2.

Intent-to-Treat Sample: A Comparison of Explained Variances (R2) for Mean PTSD Symptom Cluster and Total Scores With a Linear Versus Quadratic Fit for Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive-Processing Therapy (CPT)

| Treatment | R2 (%) | df | F | Sig F | b0 (Sig t) | b1 (Sig t) | b2 (Sig t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE: Reexperiencing | |||||||

| Linear | 62 | 3 | 4.85 | .11 | 8.21 (0.01) | −0.76 (0.11) | |

| Quadratic | 96 | 2 | 27.57 | .03 | 4.85 (0.03) | 2.12 (0.08) | −0.48 (0.05) |

| CPT: Reexperiencing | |||||||

| Linear | 63 | 3 | 5.19 | .11 | 8.48 (0.01) | −0.90 (0.11) | |

| Quadratic | 96 | 2 | 25.54 | .04 | 4.62 (0.05) | 2.40 (0.10) | −0.55 (0.05) |

| PE: Avoidance | |||||||

| Linear | 88 | 3 | 22.31 | .02 | 15.01 (0.01) | −1.62 (0.02) | |

| Quadratic | 99 | 2 | 185.74 | .01 | 11.58 (0.01) | 1.32 (0.10) | −0.49 (0.02) |

| CPT: Avoidance | |||||||

| Linear | 94 | 3 | 43.95 | .01 | 15.03 (0.01) | −1.75 (0.01) | |

| Quadratic | 99 | 2 | 99.99 | .01 | 12.55 (0.01) | 0.38 (0.62) | −0.35 (0.08) |

| PE: Arousal | |||||||

| Linear | 85 | 3 | 16.43 | .03 | 11.81 (0.01) | −1.13 (0.03) | |

| Quadratic | 98 | 2 | 59.49 | .02 | 9.12 (0.01) | 1.18 (0.18) | −0.38 (0.05) |

| CPT: Arousal | |||||||

| Linear | 90 | 3 | 26.31 | .01 | 11.95 (0.01) | −1.23 (0.01) | |

| Quadratic | 100 | 2 | 549.54 | .01 | 9.50 (0.01) | 0.86 (0.05) | −0.35 (0.01) |

| PE: Total PSS | |||||||

| Linear | 82 | 3 | 13.54 | .03 | 35.01 (0.01) | −3.50 (0.03) | |

| Quadratic | 99 | 2 | 97.10 | .01 | 25.54 (0.01) | 4.61 (0.08) | −1.35 (0.03) |

| CPT: Total PSS | |||||||

| Linear | 87 | 3 | 20.34 | .02 | 35.46 (0.01) | −3.91 (0.02) | |

| Quadratic | 99 | 2 | 101.91 | .01 | 26.92 (0.01) | 3.41 (0.15) | −1.22 (0.04) |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; Sig = significant; PSS = PTSD Symptom Scale.

Table 3.

Therapy Completer Sample: A Comparison of Explained Variances (R2) for Mean PTSD Symptom Cluster and Total Scores With a Linear Versus Quadratic Fit for Prolonged Exposure (PE) and Cognitive-Processing Therapy (CPT)

| Treatment | R2 (%) | df | F | Sig F | b0 (Sig t) | b1 (Sig t) | b2 (Sig t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE: Reexperiencing | |||||||

| Linear | 49 | 3 | 2.94 | .18 | 8.16 (0.01) | −0.73 (0.18) | |

| Quadratic | 94 | 2 | 17.12 | .05 | 4.04 (0.07) | 2.80 (0.09) | −0.59 (0.06) |

| CPT: Reexperiencing | |||||||

| Linear | 63 | 3 | 5.14 | .11 | 8.35 (0.01) | −0.88 (0.11) | |

| Quadratic | 96 | 2 | 21.77 | .04 | 4.61 (0.05) | 2.32 (0.11) | −0.53 (0.06) |

| PE: Avoidance | |||||||

| Linear | 88 | 3 | 23.11 | .02 | 15.83 (0.01) | −1.78 (0.02) | |

| Quadratic | 98 | 2 | 66.79 | .01 | 12.28 (0.01) | 1.26 (0.27) | −0.51 (0.07) |

| CPT: Avoidance | |||||||

| Linear | 94 | 3 | 51.56 | .01 | 14.93 (0.01) | −1.74 (0.01) | |

| Quadratic | 98 | 2 | 54.01 | .02 | 12.89 (0.01) | 0.00 (1.00) | −0.29 (0.18) |

| PE: Arousal | |||||||

| Linear | 83 | 3 | 14.67 | .03 | 12.08 (0.01) | −1.18 (0.03) | |

| Quadratic | 99 | 2 | 69.80 | .01 | 9.04 (0.01) | 1.42 (0.13) | −0.43 (0.04) |

| CPT: Arousal | |||||||

| Linear | 87 | 3 | 20.19 | .02 | 11.97 (0.01) | −1.22 (0.02) | |

| Quadratic | 100 | 2 | 325.04 | .01 | 9.23 (0.01) | 1.13 (0.05) | −0.39 (0.01) |

| PE: Total PSS | |||||||

| Linear | 79 | 3 | 11.46 | .04 | 36.05 (0.01) | −3.69 (0.04) | |

| Quadratic | 98 | 2 | 52.18 | .02 | 25.38 (0.01) | 5.45 (0.12) | −1.52 (0.05) |

| CPT: Total PSS | |||||||

| Linear | 87 | 3 | 20.25 | . 02 | 35.22 (0.01) | −3.85 (0.02) | |

| Quadratic | 98 | 2 | 68.16 | .01 | 26.95 (0.01) | 3.23 (0.22) | −1.18 (0.06) |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; Sig = significant; PSS = PTSD Symptom Scale.

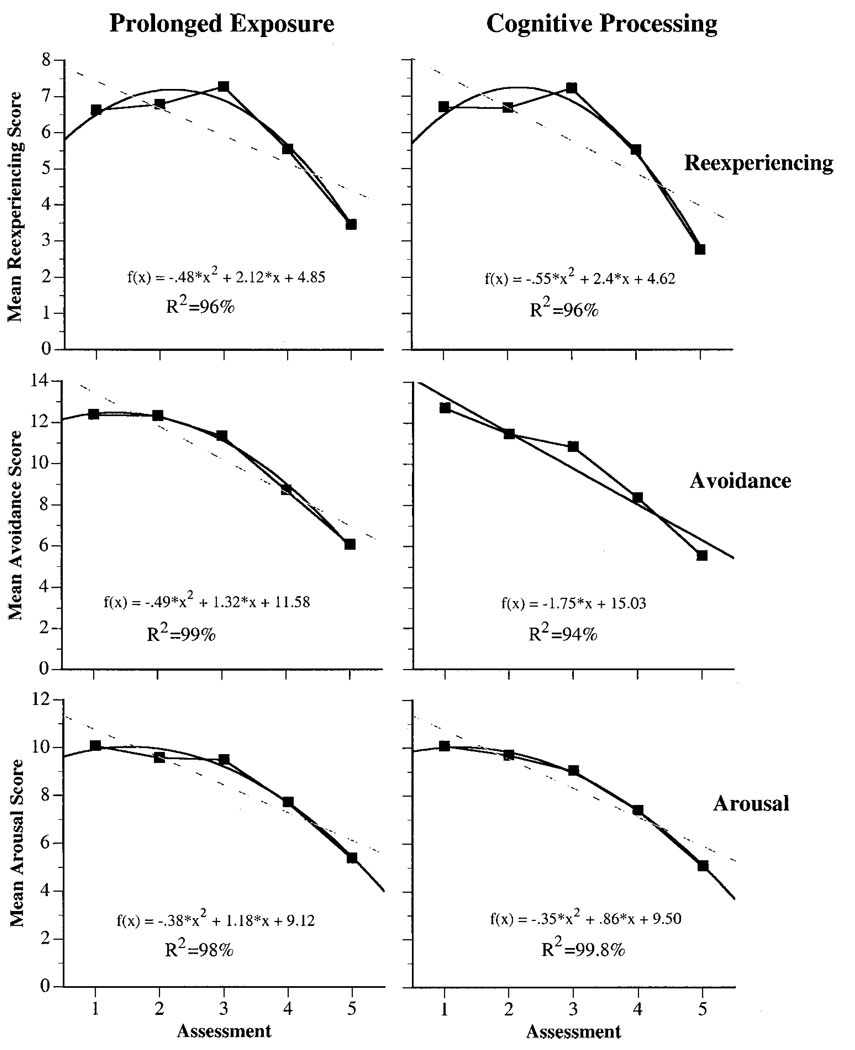

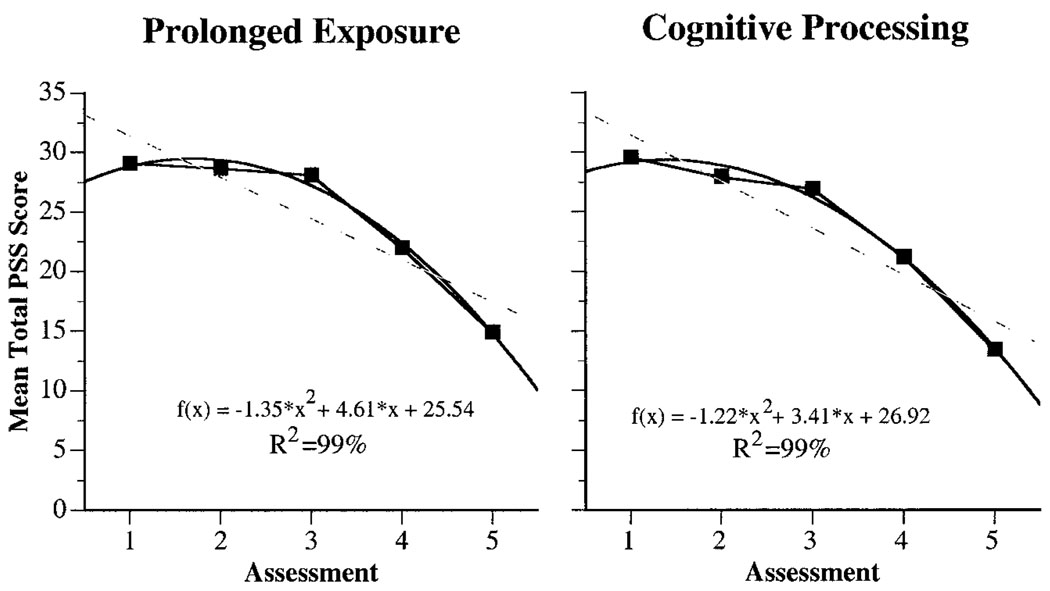

Next, the mathematical equations for the functions of best fit were derived for all mean symptom cluster and mean total PSS scores for PE and CPT. Figures 1 and 2 depict the lines of best fit, the mathematical equations, and explained variances for the mean PTSD symptom cluster and mean total PSS scores for PE and CPT for the intent-to-treat sample. As is evident from Tables 2 and 3, the lines of best fit, the mathematical equations, and explained variances for the mean PTSD symptom cluster and mean total PSS scores for PE and CPT for the therapy completers were comparable with those seen for the intent-to-treat sample.

Figure 1.

Intent-to-treat sample: the lines of best fit, mathematical functions, and explained variances for the mean posttraumatic stress disorder symptom cluster scores for prolonged exposure and cognitive-processing therapy. Dashed lines represent lines of less optimal fit for comparative purposes.

Figure 2.

Intent-to-treat sample: the lines of best fit, mathematical functions, and explained variances for the mean total PSS scores for prolonged exposure and cognitive-processing therapy. Dashed lines represent lines of less optimal fit for comparative purposes. PSS = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale.

In the final step, we conducted a series of analyses to examine the pattern of dropouts for PE (n = 34) and CPT (n = 29). For both therapies, a significantly larger proportion of women dropped out before Session 4 compared with after Session 4. Although the number of women who dropped out before Session 4 was greater for PE (79%) compared with CPT (69%), this difference between the two groups was not statistically significant, χ2(1, N = 63) = 0.90, ns.

Discussion

The analyses revealed several interesting findings. First, the reexperiencing symptoms in PTSD initially became worse before they became better in both PE and CPT. This finding can be explained by the fact that the clients in the study were fairly chronic in their PTSD symptomatology. On average, the length of time between the rape and the point at which therapy was initiated was 8.5 years. The clients usually reported that they tried to deal with the traumatic event by making efforts to avoid situations, thoughts, or feelings related to the trauma. When they came into therapy, the goal shifted from the use of avoidance-related coping techniques to the use of trauma-focused strategies that help the clients to process the feelings and thoughts related to the trauma material. This probably explained the initial rise in reexperiencing symptoms before the eventual dissipation.

The arousal symptoms showed an interesting pattern for both PE and CPT conditions. As depicted in Figure 1, it appears that the arousal symptoms show a very small decline and are almost static between Assessments 1 and 4. A perusal of the therapy protocols reveals that clients in both therapy conditions had one exposure session before the beginning of Session 4. In PE, the first imaginal exposure took place in Session 3. In CPT, the clients were asked to write a complete account of the rape for homework after Session 3 and bring it with them to Session 4. It stands to reason that the autonomic arousal would be higher in the initial sessions as the clients delve into the trauma-related details. When the clients continued the task of trauma-related information processing, the arousal symptoms started to show a sharper decline.

As is apparent from Figure 1, the avoidance symptoms with CPT showed a linear decline, in contrast with PE, where a quadratic function provided a better fit for the avoidance data. This finding may be explained by the fact that PE uses both imaginal and in vivo exposures to bring about information processing of trauma-related material in therapy. It is probably the case that intensive exposures, although effective at bringing about eventual habituation in PTSD symptoms, are more likely to bring about an immediate increase in avoidance symptoms. This is in contrast to CPT, where techniques of cognitive therapy constitute the primary therapeutic component. Further, the two exposure sessions in CPT are qualitatively different from those in PE in that the client is not instructed to engage with the trauma memory in the present tense for a duration of 45–60 min. Rather, they are asked to write about the account and read it over without a specified time limit.

An examination of the plot in Figure 2 reveals that PTSD symptoms showed little change or became slightly worse between Assessments 1 and 3. Clinically, this is an important finding because analysis of drop-out data suggests that the risk for dropping out of therapy is the greatest before Session 4 for both treatments. Both therapies initially focus on educating the clients about PTSD symptoms and orienting them to the specific treatment modality. It is important for the therapist to teach the clients that their symptoms are going to initially exacerbate, but if the clients stay with the protocol and do the therapeutic work expected of them, the symptoms will eventually decline. This might be especially relevant to the PE protocol, where avoidance symptoms show a pattern of initial increase before dissipating with continued exposures.

It is apparent that the PTSD symptoms show a dramatic shift after the first exposure session. This suggests that the exposure component may be the active ingredient of change in both the PE and CPT conditions. Research studies using a dismantling design could help determine whether this is indeed the case. Further, within PE, this design could also be used to determine the relative efficacy of imaginal exposures as compared with in vivo exposures. The importance of this is underscored by the finding that when imaginal exposures were used without in vivo exposures to treat chronic PTSD in victims of multiple traumas (Tarrier et al., 1999), the treatment effect sizes were smaller compared with the effect sizes obtained with trials that used a combination of imaginal and in vivo exposures (Devilly & Foa, 2001).

A secondary question of interest is to determine the amount of exposure needed to bring about a remission in the clinical symptoms for this population. Although parametric studies could answer this question, they would have to be designed with long-term follow-up assessments in mind. Even if limited exposure proves to be efficacious in the short-term, it would be important to determine whether the effects of this limited exposure were long lasting. In other words, it would be important to determine whether limited exposure was as effective as the standard exposure protocol in preventing long-term symptom relapse.

Finally, the total time duration for both PE and CPT, as set in the standardized treatment protocols, appears to be adequate for bringing about remission in PTSD symptoms. The total PSS score for both PE and CPT decreased from moderate–severe to mild symptoms by the end of therapy. The mathematical functions can, therefore, provide some utility in predicting the treatment course for this specific population assigned to these particular therapies. The information derived from such functions is also useful at a more pragmatic level for clinical practitioners in that it allows for more data-based decisions related to allocation of a specific number of therapy sessions for clients with a specific symptom profile. It is suggested that, although basic research can be used to provide an empirical basis for short-term therapy protocols for various disorders, it is the extension of the findings from the research to the clinical setting that allows for establishing the credibility of psychology as a science in the eyes of the community and eventually allows for policy-making decisions that are based on scientific facts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant NIH-1 R01-MH51509-06 from the National Institute of Mental Health, awarded to Patricia A. Resick. We thank Terri Weaver, Millie Astin, Linda Sharpe-Taylor, Catherine Feuer, Amy Williams, Kathleen Chard, and Janine Broudeur for their assistance in conducting therapy with the clients seen through the study. In addition, we thank Mindy Mechanic, Kathleen Chard, Terese Evans, Gail Pickett, Katie Berezniak, Dana Cason, Leslie Kimball, Debra Kaysen, Miranda Morris, and Jennifer Bennice for conducting diagnostic interviews. We also acknowledge the work of Angie Waldrop, Anouk Grubaugh, Mary Uhlmansieck, Meg Milstead, Guinevere Erwin, Stacy Isermann, Nancy Hansen, Jennifer Boyce, Terri Portell, and Karen Wright for assistance with data entry.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. The Behavior Therapist. 1990;18:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Castonguay LG. What is the scientific meaning of empirically supported therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:136–142. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Miranda J. Between-group psychotherapy outcome research and basic science. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55:147–158. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199902)55:2<147::aid-jclp2>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Foa EB. The investigation of exposure and cognitive therapy: Comment on Tarrier et al. (1999) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:114–116. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LH, Meadows EA, Street GP. A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:194–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hearst DE, Dancu CV, Hembree E, Jaycox LH. Prolonged exposure (PE) manual. Philadelphia: Medical College of Pennsylvania, Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute; 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, Murdock TB. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive–behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norusis MJ. SPSS 6.1 base system user’s guide, Pt. 2. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, Walsh A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N. What can be learned from clinical trials? Reply to Devilly and Foa (2001) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Pilgrim H, Sommerfield C, Faragher B, Reynolds M, Graham E, Barrowclough C. A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:13–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]