Abstract

The secreted SLIT glycoproteins and their Roundabout (ROBO) receptors were originally identified as important axon guidance molecules. They function as a repulsive cue with an evolutionarily conserved role in preventing axons from migrating to inappropriate locations during the assembly of the nervous system. In addition the SLIT-ROBO interaction is involved in the regulation of cell migration, cell death and angiogenesis and, as such, has a pivotal role during the development of other tissues such as the lung, kidney, liver and breast. The cellular functions that the SLIT/ROBO pathway controls during tissue morphogenesis are processes that are dysregulated during cancer development. Therefore inactivation of certain SLITs and ROBOs is associated with advanced tumour formation and progression in disparate tissues. Recent research has indicated that the SLIT/ROBO pathway could also have important functions in the reproductive system. The fetal ovary expresses most members of the SLIT and ROBO families. The SLITs and ROBOs also appear to be regulated by steroid hormones and regulate physiological cell functions in adult reproductive tissues such as the ovary and endometrium. Furthermore several SLITs and ROBOs are aberrantly expressed during the development of ovarian, endometrial, cervical and prostate cancer. This review will examine the roles this pathway could have in the development, physiology and pathology of the reproductive system and highlight areas for future research that could further dissect the influence of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in reproduction.

Keywords: SLIT, ROBO, proliferation, migration, apoptosis, adhesion, angiogenesis

Introduction

The Roundabout (robo) gene encodes a transmembrane receptor that was initially identified in Drosophila (Seeger et al., 1993). Six years later the Drosophila Slit protein was identified as the ligand for the Robo receptor (Brose et al., 1999). There is a wealth of literature that supports an evolutionary conserved role for the Slit-Robo interaction in guiding axons during development of the nervous system (reviewed by Andrews et al., 2007). A prime example is during the formation of the central nervous system in the midline. The Slit ligand, secreted by glia cells along the midline, binds to Robo receptors expressed on crossing axons. This paracrine interaction acts as a repulsive cue to prevent the crossing axons from re-crossing the midline. The Slit-Robo interaction has a similar function during the development of other processes in the nervous system including formation of the olfactory tract, optic chiasm, optic tract, forebrain and hindbrain (reviewed by Andrews et al., 2007). Mounting evidence suggests that the Slit-Robo interaction also acts as a guidance cue during the development of a variety of organs (reviewed by Hinck, 2004). Furthermore, a loss of the Slit-Robo signal has been implicated in the aberrant growth and migration of cells that occurs during cancer development (reviewed by Chédotal et al., 2005). However whether the Slit/Robo system has an important function in reproductive tissues is not well understood. This review will summarise the past and current literature to provide an overview of the cellular processes that the Slit/Robo system is thought to regulate. We will then discuss how, from these studies and present research, their potential roles in the reproductive system are starting to unravel.

Summary of the structure and signalling of Slits and Robos

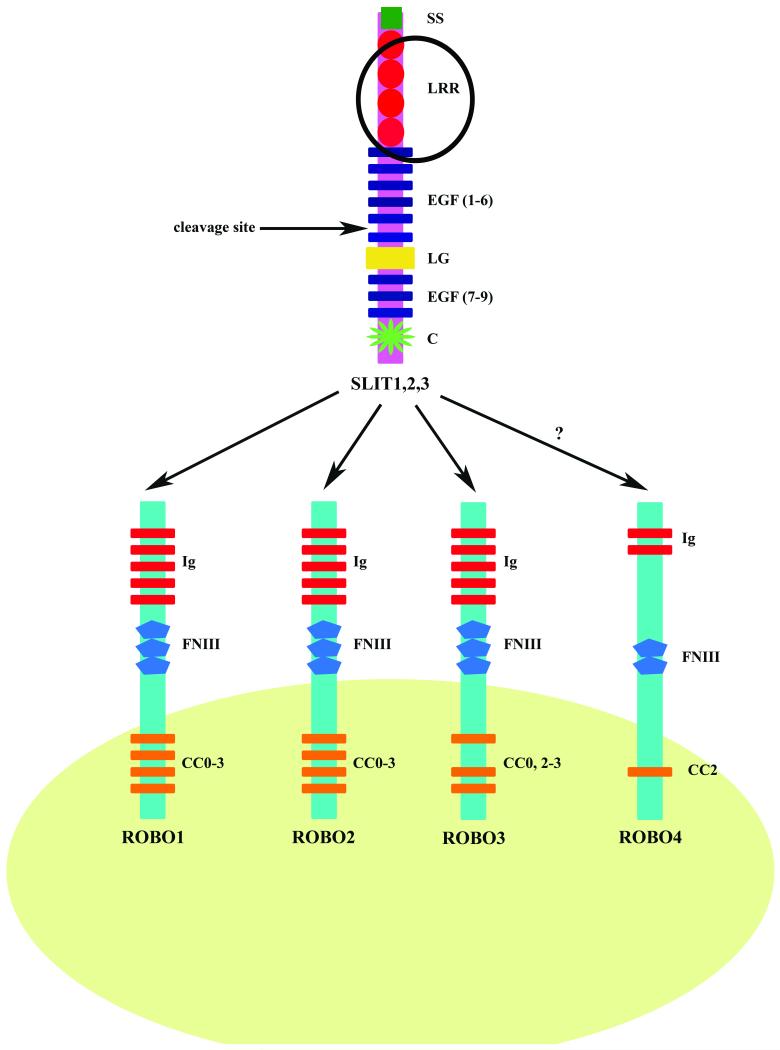

While invertebrates have a single Slit protein; vertebrates have three homologous Slits named Slit1, Slit2 and Slit3. Since they lack any hydrophobic sequences that might indicate a transmembrane domain, they are predicted to be secreted proteins associated with the extracellular matrix. The protein sequence of all Slits shows a high degree of conservation and have the same structure: an N-terminus signal peptide; four tandem leucine-rich repeat domains (LRR) termed D1-D4; six epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains; a laminin G-like domain; a further one (invertebrates) or three (vertebrates) EGF-like domains and a C terminal cysteine knot domain (Brose et al., 1999) (Fig. 1). It is possible that Slits can be cleaved into N-terminal and C-terminal fragments as there is a putative proteolytic site between EGF5 and part of EGF6 in Drosophila Slit, C. elegans Slit, rat Slit1, rat Slit3 and human SLIT2. In the context of axon guidance, it seems that the N-terminal Slit fragment retains full biological activity, as a Robo ligand, while the C terminal fragment is inactive (Nguyen-Ba-Charvet et al., 2001).

Figure 1. The domain structure of the vertebrate SLIT and ROBO proteins.

All three vertebrate SLIT proteins have the same structure. From the N-terminus: a putative signal peptide (SS); four tandem leucine rich repeat domains (LRR); six epidermal growth factor (EGF) like domains; a laminin G (LG) like domain; a further three EGF-like domains and a C terminal cysteine knot (C) domain. A putative proteolytic cleavage site has been mapped to EGF5 and part of EGF6. Four ROBO receptors have been identified in vertebrates. ROBO1, ROBO2 and ROBO3 share a common extracellular domain structure of five immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domains and three fibronectin type 3 (FNIII) repeats. The intracellular domains of ROBO1 and ROBO2 share the same conserved cytoplasmic motifs (CC0, CC1, CC2 and CC3). The CC1 motif is absent in ROBO3. ROBO4, which has the lowest homology with other ROBO family members, contains only two Ig and FNIII domains along with one CC motif, CC2. The second LRR domain of SLIT along with IG1 and IG2 of ROBO are essential for the ligand-receptor interaction. The LRR domain is circled to highlight its importance in the SLIT-ROBO interaction. SLIT has the same affinity for ROBO1-3 receptors. However whether ROBO4 is receptor for SLIT is debatable.

Although C. elegans can function with a single Robo receptor, three Robo proteins were identified in Drosophila and they were named: Robo1; Robo2 and Robo3. Four Robo receptors have been characterised in vertebrates however: Robo1/Dutt1; Robo2; Robo3/Rig-1 and Robo4/Magic Roundabout. Robo1, Robo2 and Robo3 share a common extracellular domain structure that is reminiscent of cell adhesion molecules. This region contains five immunoglobulin-like (Ig) domains followed by three fibronectin type 3 (FN3) repeats (Fig. 1). The D2 LRR domain of the Slits and IG1 and IG2 of the Robos are evolutionary conserved and are crucial for the binding interaction in vertebrates and invertebrates. However Robo4 is unusual in that it contains only two Ig and FN3 domains (reviewed by Hohenester, 2008) and the major Slit binding residues within IG1 are not conserved. It has therefore been suggested that Robo4 may not be a bona fide Robo receptor (Seth et al., 2005). However recent research suggests that SLIT2 does indeed bind to the ROBO4 receptor (Jones et al., 2008).

In order to direct changes in cell motility, the binding of Slit to the Robo receptor leads to reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton. This interaction is enhanced, in an evolutionary conserved way, by heparin sulphate proteoglycans (Ronca et al., 2001). The binding of the Slits modifies the cytoplasmic domains of the Robo receptors. These cytoplasmic domains are highly divergent through different species but there are four conserved motifs that occur in various combinations in different Robos (Fig 1). Actin polymerisation is regulated by several adaptor proteins that can bind to the cytoplasmic motifs of the Robo receptors. This has been elegantly reviewed elsewhere (Hohenester, 2008) and potential Robo adaptor proteins, in the context of the nervous system, include abelson tyrosine kinase, enabled, slit-robo Rho GTPase activating protein (srGAP), son of sevenless (SOS) and Dreadlocks (Dock) (Bashaw et al., 2000; Wong et al., 2001; Yang and Bashaw, 2006). A Slit-dependent inactivation of the RhoGTPase Cdc42 directly alters the actin cytoskeleton and an associated increased activity of the RhoGTPase Rac 1 augments the adhesive strength of cadherin mediated intracellular contacts.

SLIT-ROBO signalling can also promote cell adhesion by stimulating the interaction between E-cadherin and β-catenin at the plasma membrane. Consequently clumps of cells are less prone to cell-cell dissociation and scattering (Prasad et al., 2004; Prasad et al., 2008; Stella et al., 2009). As well as migration and adhesion Slit action can regulate other cellular processes involved in cell growth. It can inhibit hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and β-catenin activity (Prasad et al., 2004; Prasad et al., 2008; Stella et al., 2009) and this leads to inhibition of other signal transduction pathways including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and p44/42 MAP kinase activity. Therefore in addition to a well-described function in controlling cytoskeletal rearrangements affecting cell migration, the Slit/Robo pathway can also regulate other cellular processes including cell proliferation and survival.

The Slit-Robo interaction and organogenesis

With the possible exception of Slit1 and Robo3, expression of the Slits and Robos is regulated in a spatial and temporal manner during development in a wide variety of non-neuronal tissues (reviewed by Hinck, 2004). Gonadal development, for example, involves tightly regulated cell migration, proliferation and cell death. We have demonstrated that the Slit-Robo system is expressed during sheep fetal ovary development (Dickinson et al., 2009a). Expression of Robo2 and Robo4 was maximal during day 60-70 of gestation, corresponding to the early stages of follicle formation. In the developing primordial follicle, Robo1 was localised to pre-granulosa cells while Robo2 and Slit2 were localised to the oocytes. Although Robo4 is thought to be expressed primarily in the vasculature (Seth et al., 2005) we could also localise this protein in the germ cells suggesting that it may have a role outside of the vascular system. The role of the Slit-Robo interaction in the fetal ovary and its relationship to germ and somatic cell migration however has not yet been clarified. Interestingly the increased Slit-Robo expression in the fetal ovary occurs at the same time as a reduction in the number of proliferating oocytes (Dickinson et al., 2009a) and Slits have an anti-proliferative role in the nervous system (Andrews et al., 2008). Whether the Slit/Robo system regulates the development of other reproductive tissues is not known at present. However the Slit/Robo system is involved in formation of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and supraoptic nucleus. These nuclei contain neuroendocrine cells that modulate pituitary secretion, suggesting that the Slit-Robo interaction may have a role in the formation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (Xu and Fan 2008).

Mouse models with deletions in certain Slits and Robos have also implicated this pathway in morphogenesis of other tissues throughout the body. Robo1 homozygous mutant mice frequently died at birth from respiratory failure. These mice had lung defects that included abnormal bronchioles, possibly caused by aberrant branching (Xian et al., 2001). Slit2 and Robo2 homozygous mutant mice had very similar phenotypes and died shortly after birth from kidney abnormalities (Grieshammer et al., 2004). These mouse models suggested that Slit2-Robo2 signalling suppresses supernumerary bud formation possibly by directly regulating transcription or translation of genes encoding crucial morphogenetic cues such as Glial Cell Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF). Recently Slit3 homozygous mutant mice were generated which also have kidney defects (Liu et al., 2003). These Slit3 mutant mice also had an enlarged right ventricle in their heart (Liu et al., 2003). The Slit-Robo interaction seems to play an important role in the development of the heart. In early heart tube genesis in Drosophila Slit, Robo1 and Robo2 guide migrating cardioblasts and pericardial cells in the dorsal midline. Furthermore they regulate adhesion and alignment between groups of migrating cardioblasts. Slit-Robo signalling seems to hinder E-cadherin activity and this is crucial to the formation of the lumen in the Drosophila heart (Santiago-Martinez et al., 2006). Likewise Slit2 is thought to act as an adhesive cue during ductal morphogenesis in the mammary gland (Strickland et al., 2006). Furthermore these studies suggest that Slit/Robo signalling involves both the autocrine and paracrine interactions that we observed during sheep fetal ovary development (Dickinson et al., 2009a). Overall during organogenesis, the Slit/Robo pathway regulates numerous processes including cell proliferation, migration and adhesion that seem to be important in the development of disparate tissues including those of the reproductive system.

The SLIT-ROBO interaction in reproductive and hormone dependent cancers

Pathways with crucial roles in tissue growth and development are often dysregulated during tumorigenesis. The SLIT/ROBO interaction is no exception and there is accumulating evidence to indicate that it has a fundamental function during cancer development (reviewed by Chédotal et al., 2005). The majority of published research has indicated that ROBO1/DUTT1, ROBO2, SLIT1, SLIT2 and SLIT3 are candidate tumour suppressor genes that are inactivated through deletions and hypermethylation of their promoter regions in a variety of epithelial tumour types, including cervical cancer (Narayan et al., 2006). In addition deletion of the SLIT2 locus was associated with poor survival in cervical cancer patients (Singh et al., 2007). Conversely however, a recent study implied that tumour SLIT2 and ROBO1 expression may be higher in patients with recurrent endometrial cancer in contrast to those without recurrence (Ma et al., 2009).

While there is no evidence in the literature that the SLITs and ROBOs are inactivated through promoter region hypermethylation in ovarian cancer, the SLIT3 locus was deleted in ovarian germ line tumours (Faulkner and Friedlander, 2000). Around 90% of ovarian tumours are thought to originate in the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) (Leung and Choi, 2007) and we have demonstrated that ovarian cancer epithelial samples have reduced expression of SLIT2, SLIT3, ROBO1, ROBO2 and ROBO4 compared to the normal human OSE (Dickinson et al., 2009b). There is no evidence in the current literature that the SLIT-ROBO pathway has a role in testicular cancer. However decreased expression of ROBO1 was detected in prostate tumours (Latil et al., 2003).

The pivotal role of SLIT-ROBO in inhibiting aberrant migration during development has implicated this pathway in cancer progression and its inactivation is associated with increased metastasis. Re-expression of SLIT2 significantly inhibited the invasion and migration of endometrial carcinoma and ovarian carcinoma lines (Stella et al., 2009). Other published functional studies have focused on the role of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in breast cancer development. Injection of exogenous SLIT2 expressing cells into nude mice reduced breast carcinoma size by 65% (Prasad et al., 2008). In contrast to these reports one study has implied that SLIT2 may act as a chemoattractant and induce brain metastasis of breast cancer cells (Schmid et al., 2007). It therefore seems that the role of the SLIT/ROBO interaction in cancer is fundamentally important but increasingly complex.

Another role of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in tumorigenesis, like in organogenesis, may be to affect cell proliferation and death. We have shown that SLIT/ROBO activity could induce programmed cell death through Caspase-3 activation in ovarian tumour cell lines (Dickinson et al., 2009b). Loss of SLIT2, SLIT3 or ROBO1 in murine mammary gland outgrowths leads to the formation of hyperplastic disorganised lesions, an increase in the number of proliferating cells and stimulation of the SDF1/CXCR4 axis within the epithelium (Marlow et al., 2008). Research using tumours derived from other tissues have supported these findings. In SLIT2 transfected fibrosarcomas, and squamous cell carcinomas, there was a higher number of apoptotic cells and reduced proliferation (Kim et al., 2008). Furthermore, expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl and the proliferation-associated cell cycle proteins Cdk6 and Cyclin D1 was reduced in tumours from nude mice injected with SLIT2 expressing cells (Kim et al., 2008) and the proliferation rate was also lower in SLIT2 expressing hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Jin et al., 2009).

The mechanisms by which the SLIT/ROBO pathway inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis have not been determined. However there is a plausible theory about how SLIT-ROBO signalling may stimulate programmed cell death. ROBO can physically interact with another axon guidance receptor called Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) through their cytoplasmic domains (Stein and Tessier-Lavigne, 2001). This may cause DCC to disassociate from its ligand Netrin-1. SLIT2 can also bind and sequester Netrin-1 and prevent its interaction with DCC. DCC can transmit pro-survial signals in the presence of Netrin-1 but induces apoptosis, by activating Caspase 3 and 9, when its ligand is absent. ROBO binding to DCC could induce apoptosis since that association inhibits Netrin-1 signalling and the binding of SLIT to Netrin-1 could also block the transmission of pro-survival signals (reviewed by Chédotal et al., 2005). Previous research demonstrated that DCC and Netrin-1 are expressed in the ovary and expression of DCC was lost during ovarian tumorigenesis (Saegusa et al., 2000). Overall these findings indicate that the SLIT-ROBO pathway mainly suppresses tumour formation and progression by regulating processes including invasion, migration, proliferation, adhesion and aopotosis.

The Slit-Robo interaction in adult vasculature

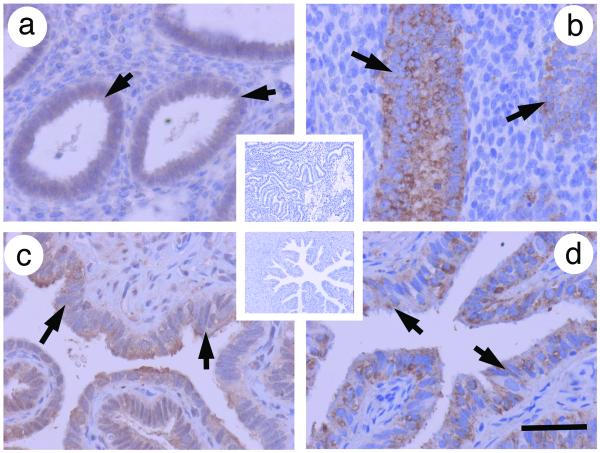

As well as its roles in fetal development and the regulation of tumorigenesis in adult cells the SLIT-ROBO pathway is also thought to have an important role in angiogenesis and the function of adult vascular system. Reproductive tissues including the ovary, endometrium and placenta are highly vascular, with dynamic and tightly regulated angiogenesis and vascular remodelling. It is therefore possible that the SLIT-ROBO interaction may regulate processes such as endothelial cell migration in these tissues. Certainly the SLITs and ROBOs are widely expressed in the human corpus luteum (CL) (Dickinson et al., 2008) and can be localised to the endometrium (Shen et al., 2009) (Fig. 2). In addition SLIT2, ROBO1 and ROBO4 are expressed in endothelial enriched cultures isolated from the human luteinising follicle (Dickinson et al., 2008) and Slit3 promotes ovine feto-placental artery endothelial cell (OFPAEC) migration and tube formation (Liao et al., 2009). Most published research investigating the role of the SLIT-ROBO pathway in the vasculature however has used cells derived from non-reproductive tissues that could provide further clues for the potential function of this system in a reproductive context.

Figure 2. Localisation of SLIT2 and ROBO1 in the endometrium and Fallopian tube.

Immunohistochemistry for SLIT2 and ROBO1 (brown) using protocols and pre-absorption controls using the techniques of reported in Dickinson et al., 2008 and Dickinson et al., 2009a. a) SLIT2 in human endometrium with insert showing negative control and b) ROBO1 in human endometrium. The epithelial glandular staining is highlighted by the arrows. c) SLIT2 in human Fallopian tube with insert showing negative control and d) ROBO1 in human Fallopian tube. The luminal epithelial staining is highlighted by the arrows. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

The exact role of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in the regulation of angiogenesis and vascular function however remains controversial. Activation of Robo4 by Slit2 inhibited vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induced migration, tube formation and permeability of mouse lung endothelial cells (Jones et al., 2008). Furthermore in their mouse models of retinal and choroidal vascular disease, the Slit2-Robo4 interaction inhibited angiogenesis and vascular leak (Jones et al., 2008). SLIT2 also inhibited human aortic smooth muscle cell (HASMC), human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cell (HUVEC) and human microvascular endothelial cell (HMVEC) migration (Liu et al., 2006; Kaur et al., 2008; Seth et al., 2005). The exact mechanism by which SLIT2 exerts its effects is unclear at present. A recent study suggested that in the absence of SLIT, ROBO1 and ROBO4 form heterodimers which keeps them in an inactive state that results in increased HUVEC migration (Kaur et al., 2008). However when SLIT2 was present it could bind to either ROBO1 or ROBO4 and inhibit HUVEC migration. In contradiction to these reports, one study was unable to convincingly demonstrate SLIT-ROBO4 binding in endothelial cells (Seth et al., 2005) and a further study suggested that a SLIT2-ROBO1 interaction may actually promote HUVEC migration (Wang et al., 2003) and facilitate angiogenesis (Stollman et al., 2009). However changes in intracellular concentrations of cyclic nucleotides and calcium can switch axon guidance cues from being repulsive to attractive or vice versa (reviewed by Chédotal et al., 2005). Therefore overall it seems that the SLIT/ROBO pathway is involved in the regulation of endothelial cell migration but the molecular effects are complex and they require further investigation particularly in reproductive tissues.

Regulation of the SLIT-ROBO interaction in adult reproductive tissues

As well as pivotal duties during organogenesis, tumorigenesis and angiogenesis, it is likely that the SLIT-ROBO interaction plays a role in regulating physiological adult cell function in reproductive tissues. We have shown that SLIT2, SLIT3, ROBO1, ROBO2 and ROBO4 are expressed in the CL of the human ovary. Furthermore expression of SLIT2, SLIT3 and ROBO2 was maximal in the late luteal phase, at the time of increasing cell death, when the CL is starting to regress (Dickinson et al., 2008). Since SLIT2, SLIT3, ROBO1 and ROBO2 were expressed in the steroidogenic luteinised granulosa cells and luteal fibroblast-like cells of the corpus luteum, the SLIT/ROBO pathway could regulate cell function in this tissue through an autocrine and/or paracrine mechanism.

During maternal recognition of pregnancy human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), from the trophoblast of the implanting blastocyst, acts through the luteinising hormone receptor to “rescue” the CL from luteolysis and maintain its structural and functional integrity (Duncan, 2000). Treating CL in vivo and primary cultures of luteinised granulosa cells in vitro with hCG, to mimic early pregnancy, caused a reduction in SLIT2, SLIT3 and ROBO2 expression (Dickinson et al., 2008). In addition we have found that hCG stimulates luteal HSD11B1 expression (Myers et al., 2007) and this results in increased local glucocorticoid production. We believe that locally generated cortisol exerts an additional luteotrophic action on luteal cells (Duncan et al., 2009). Interestingly cortisol negatively regulated SLIT2 and SLIT3 expression in primary cultures of luteal fibroblast-like cells and luteinised granulosa cells.

The SLIT/ROBO pathway also hindered the migration of luteal fibroblast-like cells from the adult human corpus luteum and the luteinising follicle (Dickinson et al., 2008). Furthermore, blocking SLIT/ROBO activity increased apoptosis, through a Caspase 3 mediated mechanism, in human luteinised granulosa cells and luteal-fibroblast like cells from the luteinising follicle (Dickinson et al., 2008). In the immune system Slit2 can regulate leukocyte chemotaxis (Wu et al., 2001). Since luteolysis of the CL involves an influx of macrophages (Duncan, 2000), further studies should investigate whether the SLIT/ROBO pathway can act on these cells. Overall these results indicate the SLIT/ROBO pathway may promote luteolysis and its expression is hormonally regulated in the adult CL.

The SLIT/ROBO pathway is also expressed in endometrium and Fallopian tube epithelium (Fig. 2) although it is not yet known if its expression is regulated in these steroid-responsive tissues. Recent research has suggested that expression of SLIT2 and ROBO1 is higher in the ectopic endometrium of ovarian endometriomas when compared to eutopic normal endometrium (Shen et al., 2009). SLIT2 expression correlated with microvascular density in endometrioma tissue and SLIT2 and ROBO1 immunostaining was also elevated in recurrent in contrast to non-recurrent endometriomas (Shen et al., 2009). It is attractive to speculate that the SLIT-ROBO interaction may have a role in endometrial function and implantation but as yet it is not known if their expression is regulated during implantation of if the SLIT-ROBO pathway is involved in trophoblast function.

The SLITs and ROBOs seem to be involved in the functional regulation of the human ovarian surface after ovulation. Our recent studies have suggested that the human OSE expresses SLIT2, SLIT3, ROBO1, ROBO2 and ROBO4. After ovulation, when the associated inflammation and follicular rupture has damaged the surface epithelium, local production of cortisol increases. Cortisol acts as an anti-inflammatory agent to promote tissue repair (Hillier and Tetsuka, 1998). Moreover, cortisol treatment caused a significant reduction in the expression of all these genes (Dickinson et al., 2009b). Since the SLITs and ROBOs promote apoptosis and inhibit cell proliferation, cortisol may inhibit the expression of these genes to allow cell division and migration to repair the surface epithelium after ovulation.

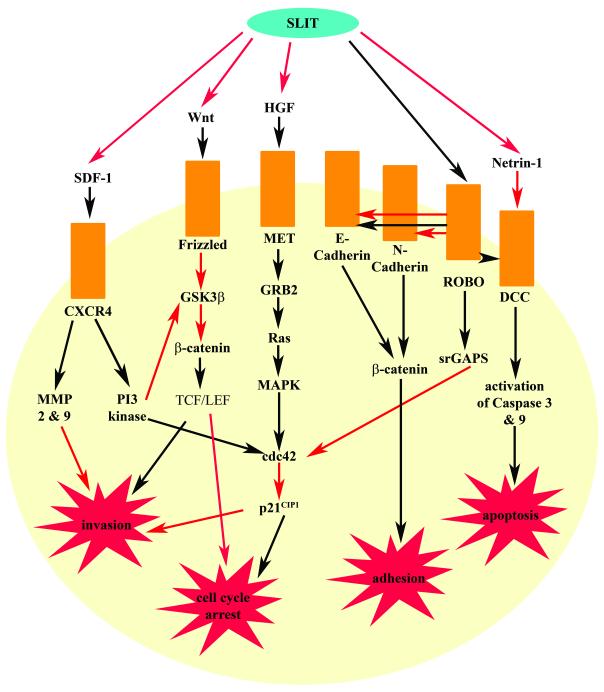

Since there are no published reports at present, it will be interesting to investigate whether SLIT/ROBO expression is regulated by additional factors in the ovary and steroid hormones in other reproductive tissues. Interestingly the Slit-Robo RhoGTPase activating protein has been identified as a potentially tamoxifen-sensitive gene in breast cancer cells (Zarubin et al., 2005). Furthermore Slit1 expression is reduced by estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators in the bone of overectomised rats (Helvering et al., 2005). The steroid regulation of the SLIT-ROBO pathway and its manipulation is therefore of major interest and further research is needed. Taken together however, the current literature suggests that there are parallels between the multiple processes that the SLIT/ROBO pathway regulates in organogenesis, tumorigenesis and normal adult physiology (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The SLIT-ROBO interaction and their regulation of cell function.

SLIT can inhibit invasion and promote a cell cycle arrest by blocking Wnt, HGF and SDF-1 signalling. The SLIT-ROBO can also prevent invasion and stimulate a cell cycle arrest directly by negatively regulating cdc42 activity. SLIT binding to ROBO also relieves inhibition of DCC by Netrin-1. This allows the activation of pro-apoptotic pathways through Caspase 3 and 9. SLIT can also bind and sequester Netrin-1 preventing its interaction with DCC and inhibitory role in apoptosis. Depending on the particular cellular environment, the SLIT-ROBO interaction can also promote and inhibit adhesion. The SLIT-ROBO interaction promotes adhesion in breast tumour cells and during mammary gland development, possibly by enhancing the association between E-cadherin and β-catenin at cell borders. However during formation of the heart lumen, SLIT-ROBO signalling antagonises E-cadherin/β-catenin mediated cell-cell adhesion. During neural development SLIT binding promotes an interaction between ROBO and N-cadherin. Subsequently β-catenin becomes disassociated from the complex and there is a reduction in cadherin mediated cell-cell adhesion. Black arrows represent promoting an activity while red arrows depict inhibiting an action.

Concluding Remarks

Along with a well-established function as an axon guidance repulsive cue, the Slit/Robo pathway has key roles during organ development, tumorigenesis and normal physiology. Importantly recent studies have suggested new functions for the SLIT/ROBO system beyond their well-described role in regulating cell migration. The SLIT-ROBO interaction seems to regulate proliferation, apoptosis, adhesion and angiogenesis in normal and tumour cells. Furthermore in the adult ovary expression of SLITs and ROBOs was physiologically regulated by steroid hormones and gonadotropins during the normal reproductive cycle. Recent research has also indicated that the SLIT/ROBO pathway is expressed in the uterus. It is likely therefore that there are disparate roles for the physiological and pathological functions of the SLIT-ROBO interaction in reproductive tissues and wider study is indicated. Future research should also investigate the possible function of the SLIT-ROBO interaction in the fetal and adult male reproductive system which is an area that has been particularly neglected so far. Furthermore the generation of transgenic mice that have mutant copies of Slit/Robo in male and female reproductive organs would provide further clues on the role of this pathway in these tissues. Identifying hormonal and other factors that may influence SLIT/ROBO expression in adult and fetal reproductive tissues is also an important area for further analysis and such research could have important implications for fertility and for the treatment of hormone dependent cancers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of Dr A.W. Horne and Dr S. McDonald in the production of Fig. 2. Dr W. Colin Duncan is supported by a Senior Clinical Fellowship from the Scottish Funding Council with laboratory support from the Chief Scientists Office (SCD/02).

References

- Andrews WD, Barber M, Parnavelas JG. Slit-Robo interactions during cortical development. Journal Of Anatomy. 2007;211:188–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews W, Barber M, Hernadez-Miranda LR, Xian J, Rakic S, Sundaresan V, Rabbitts TH, Pannell R, Rabbitts P, Thompson H, et al. The role of Slit-Robo signaling in the generation, migration and morphological differentiation of cortical interneurons. Developmental Biology. 2008;313:648–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashaw GJ, Kidd T, Murray D, Pawson T, Goodman CS. Repulsive axon guidance: Abelson and Enabled play opposing roles downstream of the roundabout receptor. Cell. 2000;101:703–15. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T. Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chédotal A, Kerjan G, Moreau-Fauvarque C. The brain within the tumor: new roles for axon guidance molecules in cancers. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2005;12:1044–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RE, Myers M, Duncan WC. Novel Regulated Expression of the SLIT/ROBO Pathway in the Ovary: Possible Role during Luteolysis in Women. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5024–34. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RE, Hryhorskyj L, Tremewan H, Hogg K, Thomson AA, McNeilly AS, Duncan WC. Involvement of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in follicle development in the fetal ovary. Reproduction. 2009a doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0182. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson RE, Fegan KS, Hillier SG, Duncan WC. Steroid regulated expression of the SLIT/ROBO pathway in human ovarian surface epithelial cells and ovarian cancer [abstract]; Proceedings of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 56th Annual Meeting; 2009b.p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan WC. The human corpus luteum: remodelling during luteolysis and maternal recognition of pregnancy. Reviews of Reproduction. 2000;5:12–7. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan WC, Myers M, Dickinson RE, van den Driesche S, Fraser HM. Luteal development and luteolysis in the primate corpus luteum. Animal Reproduction. 2009;6:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner SW, Friedlander ML. Molecular genetic analysis of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Gynecological Oncology. 2000;77:283–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U, Le M, Plump AS, Wang F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Martin GR. SLIT2-mediated ROBO2 signaling restricts kidney induction to a single site. Developmental Cell. 2004;6:709–17. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helvering LM, Liu R, Kulkarni NH, Wei T, Chen P, Huang S, Lawrence F, Halladay DL, Miles RR, Ambrose EM, et al. Expression profiling of rat femur revealed suppression of bone formation genes by treatment with alendronate and estrogen but not raloxifene. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;68:1225–38. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SG, Tetsuka M. An anti-inflammatory role for glucocorticoids in the ovaries? Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1998;39:21–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(98)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck L. The versatile roles of “axon guidance” cues in tissue morphogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2004;7:783–93. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenester E. Structural insight into Slit-Robo signalling. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2008;36:251–6. doi: 10.1042/BST0360251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, You H, Yu B, Deng Y, Tang N, Yao G, Shu H, Yang S, Qin W. Epigenetic inactivation of SLIT2 in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Biochemica and Biophysica Research Communications. 2009;379:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CA, London NR, Chen H, Park KW, Sauvaget D, Stockton RA, Wythe JD, Suh W, Larrieu-Lahargue F, Mukouyama YS, et al. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nature Medicine. 2008;14:448–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Samant GV, Pramanik K, Loscombe PW, Pendrak ML, Roberts DD, Ramchandran R. Silencing of directional migration in roundabout4 knockdown endothelial cells. BMC Cell Biology. 2008;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Zhang H, Li H, Wu TT, Swisher S, He D, Wu L, Xu J, Elmets CA, Athar M, et al. Slit2 inhibits growth and metastasis of fibrosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1411–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latil A, Chene L, Cochant-Priollet B, Mangin P, Fournier G, Berthon P, Cussenot O. Quantification of expression of netrins, slits and their receptors in human prostate tumors. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;103:306–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PC, Choi JH. Endocrine signaling in ovarian surface epithelium and cancer. Human Reproduction Update. 2007;13:143–62. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W-X, Zhang H-H, Feng L, Zheng J, Chen D-B. Slit/Robo signalling promotes placental artery endothelial cell angiogenesis via activation of multiple intracellular signalling pathways [abstract]; Proceedings Of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 56th Annual Meeting; 2009.p. 668. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Hou J, Hu X, Wang X, Xiao Y, Mou Y, De Leon H. Neuronal chemorepellent Slit2 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration by suppressing small GTPase Rac1 activation. Circulation Research. 2006;98:480–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205764.85931.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang L, Wang D, Shen H, Jiang M, Mei P, Hayden PS, Sedor JR, Hu H. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, kidney agenesis and cardiac defects associated with Slit3-deficiency in mice. Mechanisms of Development. 2003;120:1059–70. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Liu X, Geng JG, Guo S-W. Increased SLIT immunoreactivity as a biomarker for recurrence in endometrial carcinoma. American Journal of Obstetrics. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.040. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow R, Strickland P, Lee JS, Wu X, Pebenito M, Binnewies M, Le EK, Moran A, Macias H, Cardiff RD, Sukumar S, Hinck L. SLITs suppress tumor growth in vivo by silencing Sdf1/Cxcr4 within breast epithelium. Cancer Research. 2008;68:7819–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers M, Lamont MC, van den Driesche S, Mary N, Thong KJ, Hillier SG, Duncan WC. Role of luteal glucocorticoid metabolism during maternal recognition of pregnancy in women. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5769–5779. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan G, Goparaju C, Arias-Pulido H, Kaufmann AM, Schneider A, Durst M, Mansukhani M, Pothuri B, Murty VV. Promoter hypermethylation-mediated inactivation of multiple Slit-Robo pathway genes in cervical cancer progression. Molecular Cancer. 2006;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT, Brose K, Ma L, Wang KH, Marillat V, Sotelo C, Tessier-Lavigne M, Chédotal A. Diversity and specificity of actions of Slit2 proteolytic fragments in axon guidance. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:4281–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04281.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Fernandis AZ, Rao Y, Ganju RK. Slit protein-mediated inhibition of CXCR4-induced chemotactic and chemoinvasive signaling pathways in breast cancer cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:9115–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A, Paruchuri V, Preet A, Latif F, Ganju RK. Slit-2 induces a tumor suppressive effect by regulating beta -catenin in breast cancer cells. Journal Of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:26624–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800679200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronca F, Andersen JS, Paech V, Margolis RU. Characterization of Slit protein interactions with glypican-1. Journal Of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:29141–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Martínez E, Soplop NH, Kramer SG. Lateral positioning at the dorsal midline: Slit and Roundabout receptors guide Drosophila heart cell migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:12441–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605284103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Machida D, Okayasu I. Loss of DCC gene expression during ovarian tumorigenesis: relation to tumour differentiation and progression. British Journal of Cancer. 2000;82:571–8. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid BC, Rezniczek GA, Fabjani G, Yoneda T, Leodolter S, Zeillinger R. The neuronal guidance cue Slit2 induces targeted migration and may play a role in breast metastasis of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research Treatments. 2007;106:333–42. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M, Tear G, Ferres-Marco D, Goodman CS. Mutations affecting growth cone guidance in Drosophila: genes necessary for guidance toward or away from the midline. Neuron. 1993;10:409–26. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90330-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Lin Y, Hanai J, Shivalingappa V, Duyao MP, Sukhatme VP. Magic roundabout, a tumor endothelial marker: expression and signaling. Biochemica and Biophysica Research Communications. 2005;332:533–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen F, Liu X, Chen M, Geng J, Guo S-W. Increased immunoreactivity to SLIT/ROBO1 in ovarian endometriomas: a likely constituent biomarker for recurrence. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;175:479–88. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Indra D, Mitra S, Mondal RK, Basu PS, Roy A, Roychowdhury S, Panda CK. Deletions in chromosome 4 differentially associated with the development of cervical cancer: evidence of slit2 as a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Human Genetics. 2007;122:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E, Tessier-Lavigne M. Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex. Science. 2001;291:1928–38. doi: 10.1126/science.1058445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella MC, Trusolino L, Comoglio PM. The Slit/Robo system suppresses hepatocyte growth factor-dependent invasion and morphogenesis. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:642–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollman TH, Ruers TJ, Oyen WJ, Boerman OC. New targeted probes for radioimaging of angiogenesis. Methods. 2009;48:188–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland P, Shin GC, Plump A, Tessier-Lavigne M, Hinck L. Slit2 and netrin 1 act synergistically as adhesive cues to generate tubular bi-layers during ductal morphogenesis. Development. 2006;133:823–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, et al. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by Slit-Robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking Robo activity. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Ren XR, Huang YZ, Xie Y, Liu G, Saito H, Tang H, Wen L, Brady-Kalnay SM, Mei L, et al. Signal transduction in neuronal migration: roles of GTPase activating proteins and the small GTPase Cdc42 in the Slit-Robo pathway. Cell. 2001;107:209–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Feng L, Park HT, Havlioglu N, Wen L, Tang H, Bacon KB, Jiang Z, Zhang X, Rao Y. The neuronal repellent Slit inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis induced by chemotactic factors. Nature. 2001;410:948–52. doi: 10.1038/35073616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian J, Clark KJ, Fordham R, Pannell R, Rabbitts TH, Rabbitts PH. Inadequate lung development and bronchial hyperplasia in mice with a targeted deletion in the Dutt1/Robo1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:15062–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251407098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Fan CM. Expression of Robo/Slit and Semaphorin/Plexin/Neuropilin family members in the developing hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Gene Expression Patterns. 2008;8:502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Bashaw GJ. Son of sevenless directly links the Robo receptor to rac activation to control axon repulsion at the midline. Neuron. 2006;52:595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarubin T, Jing Q, New L, Han J. Identification of eight genes that are potentially involved in tamoxifen sensitivity in breast cancer cells. Cell Research. 2005;15:439–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]