Abstract

Objective

To describe the development of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) for measuring functioning and disability in accordance with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. WHODAS 2.0 is a standard metric for ensuring scientific comparability across different populations.

Methods

A series of studies was carried out globally. Over 65 000 respondents drawn from the general population and from specific patient populations were interviewed by trained interviewers who applied the WHODAS 2.0 (with 36 items in its full version and 12 items in a shortened version).

Findings

The WHODAS 2.0 was found to have high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha, α: 0.86), a stable factor structure; high test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.98); good concurrent validity in patient classification when compared with other recognized disability measurement instruments; conformity to Rasch scaling properties across populations, and good responsiveness (i.e. sensitivity to change). Effect sizes ranged from 0.44 to 1.38 for different health interventions targeting various health conditions.

Conclusion

The WHODAS 2.0 meets the need for a robust instrument that can be easily administered to measure the impact of health conditions, monitor the effectiveness of interventions and estimate the burden of both mental and physical disorders across different populations.

Resumé

Objectif

Décrire le développement de l’outil Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 de l’OMS (WHODAS 2.0), qui permet de mesurer le fonctionnement et l'incapacité conformément à la Classification internationale du fonctionnement, du handicap et de la santé. WHODAS 2.0 est une métrique standard qui garantit la comparabilité scientifique de différentes populations.

Méthodes

Une série d’études ont été réalisées à l’échelle mondiale. Plus de 65 000 personnes issues de la population générale et de populations de patients spécifiques ont été interrogées par des enquêteurs formés à cet effet et qui ont appliqué l’outil WHODAS 2.0 (comprenant 36 questions en version complète et 12 en version abrégée).

Résultats

L’outil WHODAS 2.0 présente une cohérence interne élevée (coefficient alpha de Cronbach, α: 0,86), une structure de facteur stable, une fiabilité de test-retest importante (coefficient de corrélation intraclasse: 0,98), une bonne validité concourante dans la classification des patients lorsqu’il est comparé avec d’autres instruments de mesure du handicap reconnus, la conformité avec les propriétés de l’échelle de Rasch sur les populations, ainsi qu’une réactivité de qualité (c’est-à-dire la sensibilité au changement). La fourchette des effets était comprise entre 0,44 et 1,38 pour différentes interventions de santé visant divers états de santé.

Conclusion

L’outil WHODAS 2.0 répond au besoin d’un instrument solide qui peut facilement être utilisé pour mesurer l’impact des états de santé, contrôler l’efficacité des interventions et estimer le poids des troubles mentaux et physiques parmi différentes populations.

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir la evolución del Programa de evaluación de la discapacidad 2.0 de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHODAS 2.0) para medir la funcionalidad y la discapacidad de acuerdo con la Clasificación Internacional del Funcionamiento, la Discapacidad y la Salud. El WHODAS 2.0 es una medida normalizada para garantizar la posibilidad de comparar científicamente las diversas poblaciones.

Métodos

Se han llevado a cabo varios estudios a nivel mundial. Encuestadores cualificados entrevistaron a más de 65 000 personas de la población general y de poblaciones específicas de pacientes aplicando el WHODAS 2.0 (con 36 apartados en su versión completa y 12 apartados en la versión abreviada).

Resultados

Se descubrió que el WHODAS 2.0 presentaba una elevada congruencia interna (coeficiente α de Cronbach: 0,86), una estructura factorial estable; una fiabilidad elevada de las pruebas realizadas en dos ocasiones (coeficiente de correlación intraclase: 0,98); validez simultánea adecuada en la clasificación de los pacientes, en comparación con otros instrumentos reconocidos de medición de la discapacidad; concordancia con las propiedades del modelo de Rasch a través de las poblaciones y buena capacidad de respuesta (es decir, sensibilidad al cambio). Las magnitudes del efecto oscilaron entre 0,44 y 1,38 para diferentes intervenciones sanitarias dirigidas a diversas dolencias.

Conclusión

El WHODAS 2.0 satisface la necesidad de contar con un instrumento consistente que se pueda administrar fácilmente para medir el impacto de las enfermedades, controlar la eficacia de las intervenciones y calcular la carga de los trastornos mentales y físicos en diferentes poblaciones.

ملخص

الغرض

وصف إعداد مخطط منظمة الصحة العالمية لتقييم الإعاقة 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) لقياس تأدية الوظائف والإعاقة وفقاً للتصنيف الدولي لتأدية الوظائف والإعاقة والصحة، وهو قياس معياري لضمان المقارنة العلمية بين مختلف الفئات السكانية.

الطريقة

أجريت عالمياً سلسلة من الدراسات. واختير أكثر من 65 ألف مستجيب من الفئات السكانية العامة والفئات السكانية المحددة، وأجريت معهم مقابلات استخدم فيها مخطط منظمة الصحة العالمية لتقييم الإعاقة (WHODAS 2.0) (حيث استخدم 36 بنداً في النسخة الكاملة من المخطط، واستخدم 12 بنداً في النسخة المختصرة للمخطط).

الموجودات

وجد أن مخطط منظمة الصحة العالمية لتقييم الإعاقة 2.0 لديه درجة اتساق داخلي مرتفعة (كرونباتش ألفا Cronbach's alpha، α تساوي 0.86)، وبنية قائمة على معامل ثبات؛ ودرجة معوّلية مرتفعة في الاختبار وإعادة الاختبار ( معامل الارتباط بين المجموعات: 0.98)؛ ودرجة صحة متزامنة جيدة في تقسيم المرضى عند مقارنته بسائر أدوات قياس الإعاقة المعروفة؛ وللمخطط تطابق مع صفات تدريج راش Rasch بين الفئات السكانية، ودرجة تقبُّل جيدة (أي الحساسية للتغيير). وتراوحت أحجام التأثير من 0.44 إلى 1.38 لمختلف التدخلات الصحية التي تستهدف الحالات الصحية المتنوعة.

الاستنتاج

يمكن اعتبار مخطط منظمة الصحة العالمية لتقييم الإعاقة (WHODAS 2.0) أداة قوية وسهلة الاستخدام في قياس تأثير الحالات الصحية، ورصد فعالية التدخلات، وتقدير العبء الناجم عن الاضطرابات النفسية والبدنية بين مختلف الفئات السكانية.

Резюме

Цель

Описать разработку Всемирной организацией здравоохранения Шкалы оценки инвалидности ВОЗШОИ 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) для измерения функционирования и инвалидности в соответствии с Международной классификацией функционирования, инвалидности и здоровья. ВОЗШОИ 2.0 представляет собой стандартный инструмент для обеспечения научной сопоставимости данных по различным группам населения.

Методы

Была проведена глобальная серия исследований. Специально обученные опросчики, применявшие ВОЗШОИ 2.0 (которая включала в своей полной версии 36 позиций, а в сокращенной версии – 12 позиций) провели интервью более чем с 65 тыс. респондентов, отобранных из общей численности населения и конкретных групп пациентов.

Результаты

Было установлено, что ВОЗШОИ 2.0 обладает высокой внутренней согласованностью (альфа-коэффициент Кронбаха, α: 0.86), стабильной коэффициентной структурой, высокой надежностью результатов при проверке повторным тестированием (внутриклассовый коэффициент корреляции: 0.98); хорошей текущей критериальной валидностью классификации пациентов по сравнению с другими признанными инструментами измерения инвалидности; соответствием свойствам шкалы модели Rasch в отношении разбивки по группам населения и хорошей респонсивностью (т. е. чувствительностью к изменениям). Размеры эффекта варьировались от 0,44 до 1,38 для различных медико-санитарных интервенций, адресно ориентированных на разные состояния здоровья.

Вывод

ВОЗШОИ 2.0 отвечает потребности в надежном инструменте, который может быть легко применен для измерения воздействия состояний здоровья, для мониторинга эффективности интервенций, а также для оценки бремени как физических, так и психических расстройств среди различных групп населения.

摘要

目的

对依据国际机能、残疾和健康分类用于衡量机能和残疾的世界卫生组织残疾评估表2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) 制定进行描述。WHODAS 2.0 是确保不同人群之间科学比较的标准尺度。

方法

我们在全球各地开展一系列研究。从一般人群和特定患者人群中选择了65 000人接受调查,经过专门培训的采访者运用WHODAS 2.0对他们进行采访(36项是完整版本,12项是缩减版本)。

结果

结果发现,WHODAS 2.0 表现出高度的内部一致性(Cronbach 的 alpha值:0.86),稳定的系数结构;高度的测试-再测可靠性(组内相关系数:0.98);在与其他公认的残疾测量工具对比时,在患者分类上表现出较好的共时效度;与不同人群之间的Rasch比例属性是一致的;以及良好的响应度(即针对变化的敏感度)。针对不同疾病的医疗干预措施的效果量介于0.44和1.38之间。

结论

WHODAS 2.0 具备了一款功能强大的工具的特点,易于衡量疾病的影响、监测干预措施的效果以及估计不同人群之间精神和身体疾病的治疗负担。

Introduction

Information on disability is an important component of health information, as it shows how well an individual is able to function in general areas of life. Along with traditional indicators of a population's health status, such as mortality and morbidity rates, disability has become important in measuring disease burden, in evaluating the effectiveness of health interventions and in planning health policy. Defining and measuring disability, however, has been challenging. The World Health Organization (WHO) has tried to address the problem by establishing an international classification scheme known as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).1 Nevertheless, all standard instruments for measuring disability and health need to be linked conceptually and operationally to the ICF to allow comparisons across different cultures and populations.

To address this need for a standardized cross-cultural measurement of health status and in response to calls for improving the scope and cultural adaptability of the original World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS),2–9 WHO developed a second version (WHODAS 2.0) as a general measure of functioning and disability in major life domains. This paper reports on the development strategy and the metric properties of the WHODAS 2.0.

Conceptual framework for WHODAS 2.0

The WHODAS 2.0 is grounded in the conceptual framework of the ICF and captures an individual's level of functioning in six major life domains: (i) cognition (understanding and communication); (ii) mobility (ability to move and get around); (iii) self-care (ability to attend to personal hygiene, dressing and eating, and to live alone); (iv) getting along (ability to interact with other people); (v) life activities (ability to carry out responsibilities at home, work and school); (vi) participation in society (ability to engage in community, civil and recreational activities). All domains were developed from a comprehensive set of ICF items and made to correspond directly with ICF’s “activity and participation” dimension (Table 1), which is applicable to any health condition. For all six domains, the WHODAS 2.0 provides a profile and a summary measure of functioning and disability that is reliable and applicable across cultures in adult populations.

Table 1. World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, 36 items over six domains with the corresponding International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) codesa.

| Domain | Domain question | ICF code |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Cognition | In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in: | |

| 1.1 | Concentrating on doing something for 10 minutes | d160 Focusing attention; b140 Attention functions; d110-d129 Purposeful sensory experiences |

| 1.2 | Remembering to do important things | b144 Memory functions |

| 1.3 | Analysing and finding solutions to problems in day to day life | d175 Solving problems; d130-d159 Basic learning |

| 1.4 | Learning a new task, for example, learning how to get to a new place | d1551 Acquiring complex skills |

| 1.5 | Generally understanding what people say | d310 Communicating with - receiving - spoken messages |

| 1.6 | Starting and maintaining a conversation | d3500 Starting a conversation; d3501 Sustaining a conversation |

| 2: Mobility | In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in: | |

| 2.1 | Standing for long periods such as 30 minutes | d4154 Maintaining a standing position |

| 2.2 | Standing up from sitting down | d4104 Standing |

| 2.3 | Moving around inside your home | d4600 Moving around within the home |

| 2.4 | Getting out of your home | d4602 Moving around outside the home and other buildings |

| 2.5 | Walking a long distance such as a kilometre (or equivalent) | d4501 Walking long distances |

| 3: Self-care | In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in: | |

| 3.1 | Washing your whole body | d5101 Washing whole body |

| 3.2 | Getting dressed | d540 Dressing |

| 3.3 | Eating | d550 Eating |

| 3.4 | Staying by yourself for a few days | d510-d650 Combination of multiple self-care and domestic life tasks |

| 4: Getting along | In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in | |

| 4.1 | Dealing with people you do not know | d730 Relating with strangers |

| 4.2 | Maintaining a friendship | d7500 Informal relationships with friends |

| 4.3 | Getting along with people who are close to you | d760 Family relationships; d770 Intimate relationships; d750 Informal social relationships |

| 4.4 | Making new friends | d7500 Informal relationships with friends; d7200 Forming relationships |

| 4.5 | Sexual activities | d7702 Sexual relationships |

| 5: Life activities | In the last 30 days, how much difficulty did you have in: | |

| 5.1 | Taking care of your household responsibilities | d6 Domestic life |

| 5.2 | Doing most important household tasks well | d640 Doing housework; d210 Undertaking a single task; d220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 5.3 | Getting all the household work done that you needed to do | d640 Doing housework; d210 Undertaking a single task; d220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 5.4 | Getting your household work done as quickly as needed | d640 Doing housework; d210 Undertaking a single task; d220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 5.5 | Your day-to-day work/school | d850 Remunerative employment; d830 Higher education; d825 Vocational training; d820 School education |

| 5.6 | Doing your most important work/school tasks well | d850 Remunerative employment; d830 Higher education; d825 Vocational training; d820 School education; d210 Undertaking a single task; d 220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 5.7 | Getting done all the work that you needed to do | d850 Remunerative employment; d830 Higher education; d825 Vocational training; d820 School education; d 210 Undertaking a single task; d220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 5.8 | Getting your work done as quickly as needed | d850 Remunerative employment; d830 Higher education; d825 Vocational training; d820 School education; d210 Undertaking a single task; d220 Undertaking multiple tasks |

| 6: Participation | How much of a problem do you have: | |

| 6.1 | Joining in community activities | d910 Community life |

| 6.2 | Because of barriers or hindrances in the world | d9 Community, social and civic life |

| 6.3 | Living with dignity | d940 Human rights |

| 6.4 | From time spent on health condition | Not applicable (impact question) |

| 6.5 | Feeling emotionally affected | b152 Emotional functions |

| 6.6 | Because health is a drain on your financial resources | d8700 Personal economic resources |

| 6.7 | With your family facing difficulties due to your health | Not applicable (impact question) |

| 6.8 | Doing things for relaxation or pleasure by yourself | d920 Recreation and leisure |

a The WHO DAS 2.0 also includes two preliminary sections that ask about demographic variables and general health. These sections are to be used if the WHO DAS 2.0 is used alone, but may be dropped or modified if WHO DAS 2.0 is used in conjunction with other instruments that already collect such information. A final optional section asks about the attributes and impact of identified problems.

The WHODAS 2.0 is used for many purposes. It can be used for conducting population surveys,10–15 for registers16 and for monitoring individual patient outcomes in clinical practice and in clinical trials of treatment effects.17–27

Methods

The WHODAS 2.0 was constructed through a process involving extensive review and field-testing, as described in the following sections.

Existing measures

In preparation for the development of the WHODAS 2.0, we conducted a review of existing measurement instruments and of the literature on the conceptual aspects and measurement of functioning and disability. The instruments we chose included various measures of disability, handicap, quality of life and other aspects of health, such as the ability to perform the activities of daily living (including instrumental ones), as well as global and specific measures of well-being (including subjective well-being).28,29 We compiled information from more than 300 instruments in a database showing a common pool of items, along with the origin and known psychometric properties of each instrument. An Instrument Development Task Force composed of international experts reviewed the database and pooled the items in it using the ICF as the common framework.

Research study and field testing

Since the WHODAS 2.0 was developed primarily to allow cross-cultural comparisons, it was based on an extensive cross-cultural study spanning 19 countries around the world.30 The items included in the WHODAS 2.0 were selected after exploring how health status is assessed in different cultures through a process that involved linguistic analysis of health-related terms, interviews with key informants and focus group discussions, as well as qualitative methods (e.g. pile sorting and concept mapping).

The development of the WHODAS 2.0 also involved field testing across countries in two waves (Appendix A, available at: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/). Wave 1 focused on 96 items proposed for inclusion in the instrument being developed. In these initial field testing studies, empirical feedback was obtained on the metric qualities of the proposed items, possible redundancy, screener performance in predicting the results of the full instrument, rating scales and the suitability of different disability recall time frames (e.g. 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, 1 year or lifetime). The studies also included cognitive interviews to determine how well the respondents understood the questions and reacted to the contents of the instrument. The second of field testing studies involved checking the reliability of a shortened, 36-item version of the WHODAS 2.0 by means of a standard statistical procedure, in line with classic test and item response theory (IRT).

For each wave of field testing, the overall study design required the presence of four different groups at each site, all having an equal number of subjects. The groups were composed of: (i) members of the general population in apparent good health; (ii) people with physical disorders; (iii) people with mental or emotional disorders; and (iv) people with problems related to alcohol or drug use. Subjects 18 years of age or older, divided equally into males and females, were recruited at each site.

Statistical analysis

Reliability was assessed by having a different interviewer repeat the interviews one week later, on average. The results were expressed in terms of kappa and intraclass correlation coefficients. Internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha (α) coefficient for patients at baseline. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine concurrent validity between the WHODAS 2.0 and other generic health status and disability measures. Principal components analysis was used to assess the construct validity of the scales. All items in the WHODAS 2.0 were tested against the Partial Credit Model for ordinality. The paired t-test was used for assessing the responsiveness of WHODAS 2.0 scores to clinical intervention.

Results

General application

The WHODAS 2.0 was found to perform well in widely different cultures, among different subgroups of the general population, among people with physical disorders and among those with mental health problems or addictions. Respondents found the questionnaire meaningful, relevant and interesting. The WHODAS 2.0 has already been translated into 27 languages following a rigorous WHO translation and back-translation protocol. Linguistic analysis and expert opinion survey results showed the content to be comparable and equivalent in different cultures, as was later confirmed by psychometric tests. The interview time was 5 minutes for the 12-item version and 20 minutes for the 36-item version. The 96-item version was found to require an interview time of 63−94 minutes.

In cognitive interviews, most respondents preferred the 30-day time frame and many pointed out problems in remembering with longer time frames. Regarding the concept of “difficulty”, some responders reported reasons other than health, including having too little time, too little money or too much to do – all of which were outside the definition of limitation in functioning due to a health condition.

Item reduction

Using the field trials data, we reduced to 34 the 96 items proposed for inclusion in the WHODAS 2.0 in accordance with classic test theory and item response theory. We also added two more items – one about sexual activity and another about the impact of the health condition on the family – based on suggestions from field interviewers and on the results of the expert opinion survey. A repeat survey confirmed the face validity of the resulting 36-item version. Scores in the six selected domains explained more than 95% of the variance in the total score on the 96-item version. Repeated factor analysis showed the same structure for all domains.

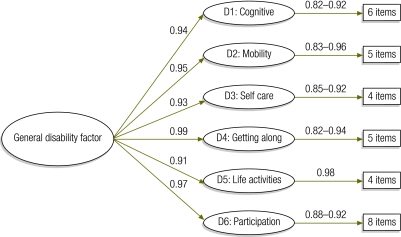

36-item factor structure

In all cultures and populations tested, factor analysis of the WHODAS 2.0 revealed a robust factor structure on two levels: a first level consisting of a general disability factor, and a second level composed of the six WHODAS representing different life areas (Fig. 1). On confirmatory factor analysis, the factor structure was similar across the different study sites and populations tested. The results of independent wave 2 field testing essentially replicated this factor structure as well.

Fig. 1.

Factor structure of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, 36-item version, in formative field studies

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency, a measure of the correlation between items in a proposed scale, was very good for WHODAS 2.0 domains. Cronbach's α coefficients for the different domains were as follows: cognition (6 items), 0.86; mobility (5 items), 0.90; self-care (4 items), 0.79; getting along (5 items), 0.84; life activities for home (4 items), 0.98; life activities for work (4 items), 0.96; and participation in society (8 items), 0.84. Total internal consistency of the WHODAS 2.0 was 0.96 for 36 items.

IRT characteristics

WHODAS 2.0 showed very good IRT characteristics, indicative of the comparability of the assessment across different populations. In wave 1 of field testing, good response functions were one of the criteria for selecting items.

In field testing wave 2, items in the 36-item version fulfilled the Rasch characteristics. All items were compatible with specific objective measurements using a Partial Credit Model.

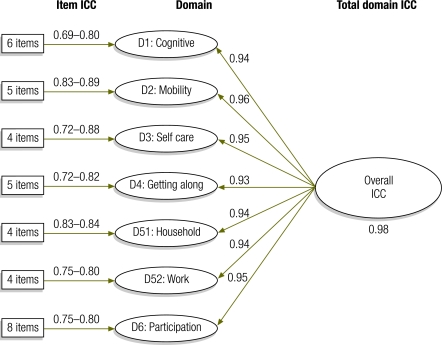

Test-retest reliability

The WHODAS 2.0 showed good test-rest reliability, a measure of the instrument's stability in repeated applications. Results of the reliability analysis are shown in Fig. 2 at the item, domain and general instrument levels. The intraclass correlation coefficient ranged from 0.69 to 0.89 at the item level and from 0.93 to 0.96 at the domain level, and it was 0.98 overall. More detailed analyses by country, region and demographic and other variables are reported separately.31

Fig. 2.

Test–retest reliability of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, 36-item versiona

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

a Field testing wave 2 (ntotal = 1565; n for the ICC depends on the domain, e.g. on how many subjects responded to all items at both time points: D1, 1448; D2, 1529; D3, 1430; D4, 1222; D5(1), 1399; D5(2), only with remunerated work, 808; D6, 1431).

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity results, a measure of how well the WHODAS 2.0 results correlate with the results of other instruments that measure the same disability constructs, are summarized in Table 2. The table shows the correlation coefficients for relevant domains in comparisons with other instruments that are less widely known, such as the WHO Quality of Life measure (WHO QOL),32 the London Handicap Scale (LHS),33 the Functional Independent Measure (FIM)34 and the Short Form Health Survey (SF).35–37 As expected, the highest correlation coefficients were found for specific domains measuring similar constructs, such as the FIM and WHODAS 2.0 mobility domains. Most other coefficients were between 0.45 and 0.65, which suggests not only that the WHODAS 2.0 and other recognized tests have similar constructs, but also that the WHODAS 2.0 is measuring something different. In addition, the WHODAS 2.0 score showed correlation in the number of days in which household tasks were reduced (r = 0.52) and in the number of absences from work lasting half a day or more (r = 0.63), respectively. The overall score on the WHODAS 2.0 was highly correlated with the overall score on the LHS (r = 0.75), the WHOQOL (r = 0.68) and the FIM (r = 0.68). It was less strongly correlated with SF mental health component scores (r = 0.17) because the SF measures signs of depression rather than functioning per se. What is important is that WHODAS 2.0 domain scores correlate highly with scores on comparable instruments designed to measure disability in specific areas (e.g. the FIM motor scale, r = 0.67 and the SF-36 Physical Component Score, r = 0.66). The correlation coefficients obtained indicate that the WHODAS 2.0 is measuring what it aims to measure (i.e. day-to-day functioning across a range of activity domains).

Table 2. Concurrent validity coefficients for the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0, 36-item and 12-item versions, versus other recognized disability measurement instruments.

| Domain | Instrument |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF 36 (n = 608–658)c | SF 12a (n = 93–94)c | WHO QOL (n = 257–288)c | LHS (n = 662–839)c | FIMb (n = 68–82)c | |

| 1 Cognition: understanding and communicating | −0.19 | −0.10 | −0.50 | −0.62 | −0.53 |

| 2 Mobility: getting around | −0.68 | −0.69 | −0.50 | −0.53 | −0.78 |

| 3 Self-care | −0.55 | −0.52 | −0.48 | −0.58 | −0.75 |

| 4 Interpersonal: getting along | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.54 | −0.50 | −0.34 |

| 5.1 Household | −0.54 | −0.46 | −0.57 | −0.64 | −0.60 |

| 5.2 Work | −0.59 | −0.64 | −0.63 | −0.52 | −0.52 |

| 6 Participation in society | −0.55 | −0.43 | −0.66 | −0.64 | −0.62 |

FIM, Functional Independent Measure; LHS, London Handicap Scale; SF, Short Form Health Survey; WHO QOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life scale.

a For correlations in domains 1 and 4, the SF mental scores were used. For all other domains the SF physical scores were used.

b For domain 1, the FIM cognition score was used as the basis of the correlation. For domain 2, the FIM mobility score was used. For all other domains, the overall FIM score was used.

c The n in parentheses represents the minimum and maximum number of subjects on which the correlations are based.

Subgroup analysis

WHODAS 2.0 is able to differentiate between special types of disabilities in patients belonging to different clinical subgroups. Domain and total scores are shown in Fig. 3. Results for disability domain profiles for different populations were all in the expected direction. For example, the group with physical health problems showed higher scores in “getting around”, whereas groups with mental health problems and drug problems showed higher scores in “getting along with people”. This confirms that the instrument has face validity. People drawn from the general population got lower scores in all domains and a lower general score than people in specific treatment subgroups. Individuals on treatment for mental problems or addictions reported more difficulty with cognitive activities and with getting along than patients on treatment for physical problems, who showed greater difficulty (i.e. scored higher) getting around and performing self-care. Participation in community activities was most difficult for drug users.

Fig. 3.

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0): domain profile by subgroup

Screening properties

In wave 2 field trials, the 12-item short version of the WHODAS 2.0 explained 81% of the variance of the 36-item version. For each domain, the 12-item version included two sentinel items with good screening properties that identified over 90% of all individuals with even mild disabilities when tested on all 36 items.

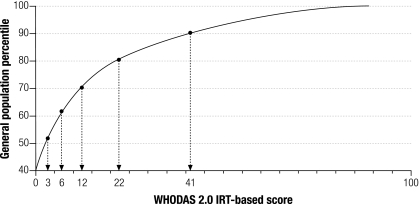

Scoring WHODAS 2.0

Multiple ways to score WHODAS 2.0 were compared in terms of their information value and practicality in daily use. As a result, two ways to compute the summary scores, namely simple and complex scoring, were found useful. In simple scoring, the scores assigned to each of the items (none, 1; mild, 2; moderate, 3; severe, 4; and extreme, 5) are summed up without recoding or collapsing response categories. Simple scoring is as practical as hand scoring and may be preferable for busy clinical settings or interviews. The simple scoring of WHODAS 2.0 is only specific to the sample at hand and should not be assumed to be comparable across populations. The psychometric properties of the WHODAS 2.0, namely its one-dimensional structure with high internal consistency, make it possible to add the scores.38 In complex scoring, also known as item response theory-based scoring,39 multiple levels of difficulty for each WHODAS 2.0 item are allowed for. Complex scoring makes more fine-grained analyses possible, since the information for the response categories is used in full for comparative analysis across populations or subpopulations. With item response theory-based scoring for WHODAS 2.0, each item response (none, mild, moderate, severe and extreme) is treated separately and the summary score is generated with a computer by differentially weighting the items and the levels of severity.

In addition to the total scores, WHODAS 2.0 also makes it possible to compute domain-specific scores for cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities (at home and at work) and social participation. We used SPSS software, version 10 (SPPS Inc., Chicago, United States of America), to compute the summary score. Both the program and the domain scores are available at: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/

WHODAS 2.0 provides standard scores for the general population derived from large international samples against which individuals or groups can be compared, as was done in the reliability and validity study conducted in wave 2 of the WHODAS 2.0 development process; and the WHO Multi-Country Survey Study.12 Fig. 4 gives the population standard scores for IRT-based scoring of the 36-item WHODAS 2.0. Accordingly, an individual with 22 positive item responses would represent the 80th percentile. Summary scores and population percentiles for item response theory-based scoring of the 12-item WHODAS 2.0 are also available. Details are available in the WHODAS 2.0 training manual40 and at: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/

Fig. 4.

Population distribution of scores on the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0), 36-item version

IRT, item response theory.

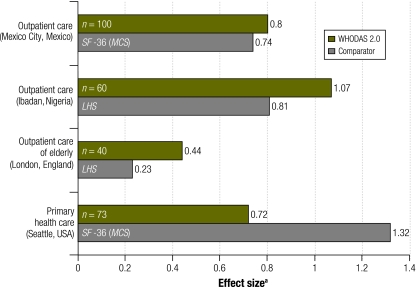

Responsiveness

When the mean standardized response (that is, the change in mean score divided by the standard deviation of the change in score) was used as a measure of effect size, the WHODAS 2.0 was found to be at least as sensitive to change as comparable functioning scales, For example, Fig. 5 shows WHODAS 2.0 responsiveness as noted in the case of treatment for depression in patients from four different countries. Effect sizes for the WHODAS 2.0, which ranged from 0.44 to 1.07, are comparable to those obtained with established functioning scales. Similar effect sizes (0.44–1.38) were obtained for interventions targeting individuals with schizophrenia, osteoarthritis, back pain and alcohol dependence.41

Fig. 5.

Responsiveness (sensitivity to change) of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0), 36-item version (SF 36), as noted in the case of treatment for depression

LHS, London Handicap Scale; MCS, mental component summary.

a The effect size represents the change in mean value divided by one standard deviation.

Discussion

Stringent tests performed during WHODAS 2.0 development have shown that the WHODAS 2.0 can be used across cultures, sexes and age groups, as well as for different types of diseases and health conditions. The instrument covers key life activities well. The12-item version of the WHODAS 2.0 can be administered in less than 5 minutes and the 36-item version in less than 20 during interviews and in 5 to 10 minutes when self-administered or administered by proxy. Scores are easily obtained and interpreted. They represent multidimensional disability based on the ICF, and the underlying factor structure is robust. Details and instructions on how to administer different versions of the WHODAS 2.0 and compute its scores can be found in the WHODAS 2.0 training manual.40

WHODAS 2.0 has good psychometric qualities, including good reliability and item-response characteristics, and its robust factor structure remains the same across cultures and in different patient populations. It shows concurrent validity when compared with other measures of disability or health status or with clinician ratings. These findings have been replicated across different countries and in a wide range of patient and general population samples. Thus, the WHODAS 2.0 can be used to assess individual patients as well as to explore differences between groups.

Field trials of the use of WHODAS 2.0 in health services research have focused on responsiveness, that is, on how well WHODAS 2.0 can detect changes following treatment under specific conditions. We use the WHODAS 2.0 to predict disability-related outcomes such as health care utilization, costs and work productivity, and we have compared its predictive validity to that of other disability measures.

In the Multi-country Survey Study that was conducted in 12 WHO Member States, WHODAS 2.0 was administered to randomly selected adults from the general population in face-to-face interviews.12 These surveys have been used to formulate a descriptive system of disability weights (i.e. utilities) for use in summary measures of population health, such as disability-adjusted life years. Econometric methods, such as time trade-off or person trade-off tools, have proved useful in eliciting disability weights. However, the application of these methods in general population surveys is problematic. Descriptive methods, such as application of WHODAS 2.0, are not only easier to apply but also yield more reliable indices for disability weights.

The WHODAS 2.0 has several limitations. It covers mainly the activities and participation domains of the ICF, so bodily impairments and environmental factors are not included. This design decision was made during the initial phase of development. However, work is under way to develop an additional module for bodily impairments.40 Furthermore, the WHODAS 2.0 is only applicable to adult populations. After the ICF for children and youth (ICF-CY) was published in 2007, plans were initiated to develop a version of the WHODAS 2.0 for children and youth.42

The WHODAS 2.0 framework can be applied in different formats for uses such as clinical interviews or telephone interviews. The feasibility and reliability of these applications are currently being determined. Computer-adaptive testing, a novel method for shortening the application, will enhance the feasibility of using the WHODAS 2.0 in different studies. Population standard norms will be continuously improved during future applications of the WHODAS 2.0. Similarly, item banking for different clinical intervention trials will enable comparative effectiveness studies.

In summary, WHODAS 2.0 has the potential to serve as a reliable and valid tool for assessing functioning and disability across countries, populations and diseases. It provides data that are culturally meaningful and comparable. Thus, it can be used as a common metric for assessing the level of functioning in individuals with different health conditions as well as in the general population. The WHODAS 2.0 can be used in surveys and in clinical research settings and it can generate information of use in evaluating health needs and the effectiveness of interventions to reduce disability and improve health.

Acknowledgements

The Task Force on Assessment Instruments also included: Elizabeth Badley, Cille Kennedy, Ronald Kessler, Michael Von Korff, Martin Prince, Karen Ritchie, Ritu Sadana, Gregory Simon, Robert Trotter and Durk Wiersma.

The following are the WHO collaborative investigators involved in the WHO/NIH Joint Project: Gavin Andrews (Australia); Thomas Kugener (Austria); Kruy Kim Hourn (Cambodia); Yao Guizhong (China); Jesús Saiz (Cuba); Venos Malvreas (Greece); R Srinivasan Murty (India, Bangalore); R Thara (India, Chennai); Hemraj Pal (India, Delhi); Matilde Leonardi, Ugo Nocentini (Italy); Miyako Tazaki (Japan); Elia Karam (Lebanon); Charles Pull (Luxembourg); Hans Wyirand Hoek (Netherlands); AO Odejide (Nigeria); José Luis Segura García (Peru); Radu Vrasti (Romania); José Luis Vásquez Barquero (Spain); Adel Chaker (Tunisia); Berna Ulug (Turkey); Nick Glozier (United Kingdom); Patrick Doyle, Katherine McGonagle, Michael von Korff (United States of America). A full list of collaborators is available at: http://www.who.int/icidh/whodas/

Funding:

The WHODAS 2.0 development was funded through the WHO/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Joint Project on Assessment and Classification of Disability (MH 35883–17).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health Geneva: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jablensky A, Schwarz R, Tomov T. WHO collaborative study on impairments and disabilities associated with schizophrenic disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1980;62:152–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb07687.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule Geneva: WHO; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M, Korton A, Cooper JE, et al. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures: a World Health Organization ten-country study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thara R, Rajkumar S, Valencha V. The Schedule for Assessment of Psychiatric Disability: a modification of the DAS-II. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:47–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardoin MP, Faccincani C, Galati M, Gavioli I, Mignolli G. Inter-rater reliability of the Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS, version II). An Italian study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26:147–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00795205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiersma D, Giel R, De Jong A, Slooff CJ. Schizophrenia: results of a cohort study with respect to cost-accounting problems of patterns of mental health care in relation to course of illness. In: Schwefel D, Zöllner H, Potthoff P, editors. Costs and effects of managing chronic psychotic patients Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1988. pp. 115-1235. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiersma D, De Jong A, Kraaijkamp HJM, Ormel J. GSDS-II: the Groningen Social Disabilities Schedule, second version 2nd edn. Groningen: University of Groningen, Department of Social Psychiatry; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Üstün TB, Sartorius N. Mental illness in general health care: an international study Chichester: John Wiley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sousa RM, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Guerra M, Huang Y, et al. Contribution of chronic diseases to disability in elderly people in countries with low and middle incomes: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Lancet. 2009;374:1821–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Mechbal A, Murray CJL, WHS Collaborating Group. The World Health Surveys. In: Murray CJL, Evans DB, eds. Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods and empiricism Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Villanueva M, Bendib L, Celik C, Sadana R, et al. WHO Multi-country Survey Study on Health and Responsiveness 2000-2001. In: Murray CJL, Evans DB, eds. Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods and empiricism Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. pp. 761-96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buist-Bouwman MA, Ormel J, De Graaf R, Vilagut G, Alonso J, Van Sonderen E, et al. ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators Psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule used in the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:185–97. doi: 10.1002/mpr.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific & World Health Organization. Training manual on disability statistics Bangkok: UNESCAP & WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallagher P, Mulvany F. Levels of ability and functioning: using the WHODAS II in an Irish context. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:506–17. doi: 10.1080/0963828042000202257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federici S, Meloni F, Mancini A, Lauriola M, Olivetti Belardinelli M. World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Schedule II: contribution to the Italian validation. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:553–64. doi: 10.1080/09638280802240498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron M, Schieir O, Hudson M, Steele R, Kolahi S, Berkson L, et al. The clinimetric properties of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II in early inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:382–90. doi: 10.1002/art.23314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlote A, Richter M, Wunderlich MT, Poppendick U, Möller C, Wallesch CW. Use of the WHODAS II with stroke patients and their relatives: reliability and inter-rater-reliability. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2008;47:31–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985168. [German.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson M, Steele R, Taillefer S, Baron M, Canadian Scleroderma Research Quality of life in systemic sclerosis: psychometric properties of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:270–8. doi: 10.1002/art.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soberg HL, Bautz-Holter E, Roise O, Finset A. Long-term multidimensional functional consequences of severe multiple injuries two years after trauma: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. J Trauma. 2007;62:461–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000222916.30253.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perini SJ, Slade T, Andrews G. Generic effectiveness measures: sensitivity to symptom change in anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2006;90:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chisolm TH, Abrams HB, McArdle R, Wilson RH, Doyle PJ. The WHO-DAS II: psychometric properties in the measurement of functional health status in adults with acquired hearing loss. Trends Amplif. 2005;9:111–26. doi: 10.1177/108471380500900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chopra PK, Couper JW, Herrman H. The assessment of patients with long-term psychotic disorders: application of the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:753–9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKibbin C, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Assessing disability in older patients with schizophrenia: results from the WHODAS-II. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:405–13. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000130133.32276.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norton J, de Roquefeuil G, Benjamins A, Boulenger JP, Mann A. Psychiatric morbidity, disability and service use amongst primary care attenders in France. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:164–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M. Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:507–14. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews G, Peters L, Teesson M. The measurement of consumer outcome in mental health: a report to the National Mental Health Information Strategy Committee Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziebland S, Fitzpatrick R, Jenkinson C. Tacit models of disability underlying health status instruments. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90319-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Bickenbach J, Trotter RT 2nd, Room R, Rehm J, et al. Disability and culture: universalism and diversity Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostanjsek N, Epping-Jordan J, Prieto L, Doyle P, Chatterji S, Rehm J, et al. Reliability of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule – WHODAS II: subgroup analyses. Available from: www.who.int//healthinfo/whodas [accessed 13 May 2010].

- 32.Sartorius N, Üstün TB. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:1403–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harwood RH, Rogers A, Dickinson E, Ebrahim S. Measuring handicap: the London Handicap Scale, a new outcome measure for chronic disease. Qual Health Care. 1994;3:11–6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.3.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD. Performance profiles of the functional independence measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72:84–9. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey; manual and interpretation guide Massachusetts: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical theories of mental test scores Reading: Addison Wesley; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Üstün TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chisholm D, Chatterji S, Chwastiak L, Glozier N, Guizhong Y, Lara-Munoz C, et al. Responsiveness of the World Health Organization Disability Assesment Schedule II (WHO DAS II) in different cultural settings and health populations. Available from: www.who.int//healthinfo/whodas [accessed 13 May 2010].

- 42.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: children and youth version Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]