Abstract

Protein glycosylation is a common post-translational modification and has been increasingly recognized as one of the most prominent biochemical alterations associated with malignant transformation and tumorigenesis. N-linked glycosylation is prevalent in proteins on the extracellular membrane, and many clinical biomarkers and therapeutic targets are glycoproteins. Here, we describe a protocol for solid-phase extraction of N-linked glycopeptides (SPEG) and subsequent identification of N-linked glycosylation sites (N-glycosites) by tandem mass spectrometry. The method oxidizes the carbohydrates in glycopeptides into aldehydes, which can be immobilized on a solid support. The N-linked glycopeptides are then optionally labeled with a stable isotope using deuterium-labeled succinic anhydride and the peptide moieties are released by peptide-N-glycosidase. In a single analysis, the method identifies hundreds of N-linked glycoproteins, the site(s) of N-linked glycosylation, and the relative quantity of the identified glycopeptides.

INTRODUCTION

Glycosylation has long been recognized as the most common protein post-translational modification. It affects protein function, such as protein localization, stability, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions 1. Differential glycosylation is a major source of protein microheterogeneity. Glycosylation plays key roles in cell communication, signaling and cell adhesion. Changes in carbohydrates in cell surface and body fluid proteins have been demonstrated in cancer and other conditions and highlight the importance of this modification 2, 3. However, studies on protein glycosylation have been complicated by the diverse structure of protein glycans and the lack of effective tools to identify the protein glycosylation site and glycan structure. For example, human protein database contains thousands of predicted N-linked glycosylated proteins, however, before high throughput methods for the identification of glycosites were developed in 2003, only 172 proteins were proven to be glycoproteins experimentally in the Protein Information Resources-Protein Sequence Database (http://pir.georgetown.edu/pirwww/search/textpsd.shtml)4.

Recently, two new methods for isolation and identification of N-linked glycopeptides in complex biological samples – solid-phase extraction of N-linked glycopeptides and glycopeptide capture using lectin-affinity column chromatography – have been reported 4, 5. In both instances, mass spectrometry is used after the isolation of the N-glycopeptides to identify the N-glycosites and quantify the relative abundance of glycopeptides using isotope coded tags.

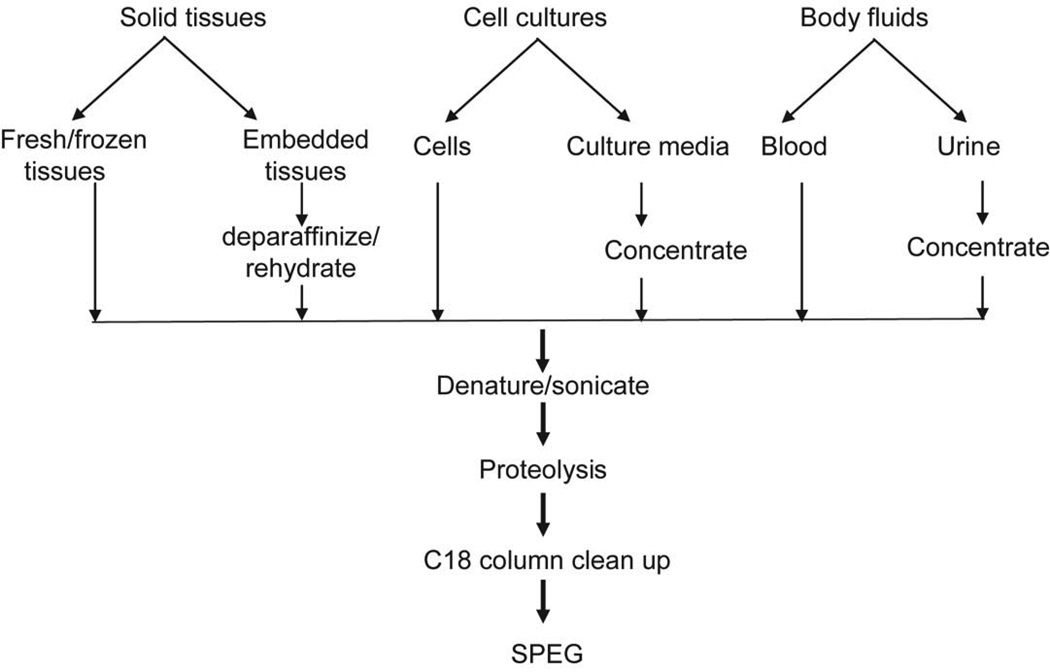

In the first method, glycoproteins are covalently conjugated to a solid support via hydrazide chemistry, non-glycosylated peptides are removed with proteolysis prior to the release of N-linked glycopeptides from solid support 5. In the modified method detailed in this protocol, (Figure 1), glycoproteins are first digested into peptides that contain both glycosylated peptides and non-glycosylated peptides, and the cis-diol groups of carbohydrates in glycopeptides are oxidized to aldehydes which then form covalent hydrazone bonds with hydrazide groups immobilized on a solid support. Non-glycosylated peptides are washed away while the glycosylated peptides remain on the solid support. For accurate quantitative analysis of N-linked glycopeptides using isotope labeling and mass spectrometry, the amino groups of the immobilized glycopeptides can be labeled with isotopic tags. For example, light (d0, containing no deuteriums) or heavy (d4, containing four deuteriums) forms of succinic anhydrides can be used to label the glycopeptides isolated from two biological samples. Lastly, the formerly N-linked glycosylated peptides are released from the solid phase using Peptide-N-Glycosidase F (PNGase F). PNGase F treatment also results in the conversion of the glycosylated asparagines to aspartic acids, thus generating a 1 unit mass shift at the site of glycosylation which is detectable using a high accuracy mass spectrometer and is diagnostic for the glycosylation site. Therefore, in a single analysis, the method identifies N-linked glycosylated proteins, the site(s) of N-linked glycosylation, and the relative quantity of the identified glycopeptides via stable isotope tagging.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of solid-phase extraction of N-linked glycopeptides. Proteins are first proteolyzed into peptides. Glycosylated peptides are then oxidized and coupled to a solid support. Non-glycopeptides are removed by successive washes. The amino-terminals of glycopeptides are labeled by succinic anhydride carrying either d0 or d4. N-linked glycopeptides are then released by PNGase F and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

In the second approach, glycopeptides are immobilized by lectin column-mediated affinity capture. After elution of glycopeptides from lectin column, peptide-N-glycosidase is then used to release the N-linked glycopeptides and the resulting peptides are subjected to mass spectrometry to identify the N-linked glycopeptides and sites of glycosylation 4. For glycopeptide capture using hydrazide chemistry, peptides containing either N-linked or O-linked oligosaccharides are conjugated to a solid support covalently. Non-glycosylated peptides can be removed by extensive washing before the release of glycopeptides, therefore the glycopeptides can be specifically enriched (over 90% enrichment 6). The specific release of different types of glycopeptides from solid support can be achieved by varying glycosidases or chemicals. For glycopeptide capture using a lectin affinity column, glycopeptides containing certain glycan structures can be selectively enriched by employing different types of lectin affinity chromatography. The specificity and reproducibility may not be easily controlled due to affinitive capture of glycopeptides.

Extracellular proteins, such as proteins expressed on the cell surface or secreted from the cell, are exposed to extracellular environments such as surrounding tissue, blood, or other body fluids. Such proteins are thus the most easily accessible for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. If present in easily accessible body fluids such as blood plasma or cerebrospinal fluid, they are also preferred candidates protein biomarkers. However, the challenge faced by all proteomic methods for the analysis of body fluids is the peculiar properties of these samples. The proteome of most body fluids is complex, consisting minimally of tens of thousands of different protein species and exhibiting a high dynamic range in protein concentration. These proteomes are also dominated by a few highly abundant proteins7, and as a result, most proteomic analyses of body fluids detect only a limited number of highly abundant proteins. While the dynamic range of protein abundances in tissues or cells is not as large as it is in body fluids, a similar situation is still observed: Proteomic analyses detect only the most abundant protein subset, comprised mostly of structural intracellular proteins. Glycosylation, especially N-linked glycosylation, is a common modification to proteins that are exposed to an extracellular environment 8. Therefore, selective isolation of N-linked glycopeptides enriches tissue and body fluid proteomes for extracellular proteins. In addition, the number of N-linked glycosylation sites in the human extracellular proteome is modest and identifiable with current proteomic technology. For example, N-glycosites, which generally contain the N-X-S/T sequence motif (where X denotes any amino acid except proline) 9, are found in just 3% of tryptic peptides from the entire human proteome, yet they represent the majority of extracellular proteins (over 70%) 10. Therefore, targeted analysis of N-glycosites significantly increases the sensitivity for low abundance glycoproteins by reducing the number of detectable peptides at each targeted mass range.

While the analysis of N-linked glycopeptides reduces sample complexity and peptide redundancy and is therefore beneficial for achieving higher coverage of the proteome per analysis, it is also apparent that it leads to the loss of some, potentially important information. First, non-glycosylated proteins are transparent to this system. Second, the availability of few N-glycosites per protein increases the challenge of identifying the corresponding protein. Third, tryptic peptides that are too short or too long to fall within the detection range of the mass spectrometer will not be identified, although this last limitation may be overcome, at least in part, by the use of proteases with cleavage specificities different from that of trypsin. Forth, removal of oligosaccharides from the N-linked glycopeptides before their analysis only identifies the N-glycosite whereas the glycan structure attached to the site is not being analyzed. Finally, releasing formerly N-linked glycopeptides from their attached oligosaccharide coalesces different oligosaccharide structures into a single peptide sequence-specific signal, thus obfuscating glycosylation changes due to oligosaccharide structure alteration 2.

SPEG has been successfully applied to the quantitative analysis of glycopeptides from complex mixtures, including serum/plasma and other body fluids. 5, 6, 11–15, the detection of glycoproteins secreted or shed into the culture medium by cells, the detection of membrane proteins and cell surface proteins from cells and tissues 16, 17, and for comparing glycoproteins in the extracellular matrix of normal and disease tissues 18. Several high abundance plasma proteins, including the most abundant plasma protein, albumin, do not appear to contain any N-glycosites and are therefore transparent to the method, allowing for more efficient identification and quantification of the lower abundance glycoproteins in blood 6. By combining quantitative analysis of N-glycosites with methods that determine relative protein changes in different proteomes, such as the cysteine tagging method 19, the occupancy of individual N-glycosites and changes therein can also be determined. This is of particular interest in studies in which changes of glycosylation occupancy are suspected, as exemplified by patients with Type I Congenital Disorders of glycosylation (CDG), in which the N-linked glycosylation pathway is deficient 20. Using this method, we have identified thousands of N-glycosites from different tissues, plasma, and other body fluids, and established a database (www.unipep.org) as a public resource for glycoprotein analysis 10.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

Hydrazide resin: Affi-Prep beads, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA

Sodium periodate: make 100 mM in water before usage (21 mg in 1 ml of water, light sensitive)

Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP): make 120 mM stock in water (Pierce, Rockford IL, molecular weight=286.65, 34.4 mg in 1 ml of water)

Iodoacetamide: make 160 mM solution in water freshly (30 mg/ml in water, light sensitive)

Potassium phosphate buffer: 100 mM, pH 8.0

Ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3): 0.1M solution pH 8.3. Make up fresh

Denaturing buffer: 8M urea in 0.4M NH4HCO3 with 0.1% SDS

Sodium chloride: 1.5 M

SDS stock solution: 10%

Standard peptide: 1 µM Angiotensin I peptide in water (Sigma-Aldrich #A9650), and 1 µM of Neurotensin peptide in water (Sigma-Aldrich #A6383)

Hydrochloric acid (HCl): 5 N

Acetic acid: 0.4%

PNGase F: New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA

Sequencing grade trypsin: Promega, Madison, WI

Acetonitrile (ACN)

BCA Protein Assay Kit – Pierce, Rockford, IL

Methanol

SDS-PAGE Gels

0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

HPLC solution A: 0.1% formic acid in water

HPLC solution B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (ACN)

Succinic-d0-anhydride: Sigma, St. Louis, MO

Succinic-d4-anhydride: C/D/N Isotopes, Pointe-Claire, Quebec, CA

Isotopic labeling solution: 2 mg/ml of succinic anhydride in Dimethylformamide (DMF)/pyridine/H2O=50/10/40 (v/v/v)

Software for sequence assignment from tandem mass spectrum: SEQUEST 21

Software for statistical evaluation of peptide sequence assignment: PeptideProphet 22

EQUIPMENT

Tube rocker

SpeedVac

C18 1cc SepPak columns – Waters, Milford, MA

Vial: Glass vials with polyethylene snap cap (Waters, Milford, MA)

HPLC: HP1100, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA

Sonicator

LCQ or LTQ ion-trap mass spectrometer: Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA

Quadrupole-time-of-flight (ESI-qTOF) mass spectrometer: Waters, Milford, MA

Peptide cartridge packed with Magic C18: Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA

FAMOS autosampler: DIONEX, Sunnyvale, CA

Microcapillary HPLC column: 10 cm × 75 µm i.d. packed with Magic C18 resin (5 µm, 100Å, Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA)

EQUIPMENT SETUP

LC-MS-MS/MS: Peptides are injected into a peptide cartridge packed with Magic C18 using a FAMOS autosampler, and then pass through a 10 cm × 75 µm i.d. microcapillary HPLC column packed with Magic C18 resin. The eluting peptides are directly ionized by electrospray ionization (ESI) and tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) are acquired by data-dependent MS/MS mode (a full-scan mass spectrum is followed by a tandem mass spectrum), where the precursor ion is selected "on the fly" from the previous scan. A selected precursor is placed in a list and dynamically excluded for 3 min from further fragmentation.

-

A linear gradient of acetonitrile from 5%–32% over 100 min at a flow rate of ~300 nl/min is applied for reverse-phase liquid chromatography using an HP1100 solvent delivery system.

HPLC gradient:Time (min) % B 0–5 5 5–105 5–32 105–115 32–80 115–125 80 125–135 80-5

PROCEDURE

Digestion of proteins to peptides

-

1

Extract proteins from variety of biological samples in denaturing buffer (Figure 2). For plasma proteins or other protein samples with a protein concentration of more than 5 mg/ml, dilute the sample at least 10 times with denaturing buffer (final protein concentration is less than 5 mg/ml). For proteins from other body fluids or cell culture medium with protein concentration less than 5 mg/ml, add solid urea, ammonium bicarbonate, and 10% SDS stock solution directly to the samples to prepare a denaturing buffer containing 8M urea, 0.4M NH4HCO3, and 0.1% SDS. For extraction of protein from cells, harvest 107 cells in 1 ml of denaturing buffer. For extraction of proteins from solid tissue, frozen tissue (100 mg) is sliced into 1~3mm3 thick pieces and incubated in 1 ml of urea buffer for 2–3 min with vortexing.

-

2

Sonicate samples for 6 minutes at 4°C with a probe sonicator to homogenize protein samples.

-

3

Determine protein concentration with BCA protein assay, and take 1 mg of proteins from crude extract for each SPEG. More protein can be used for larger scale glycopeptide preparations if reagent amounts are scaled appropriately.

-

4

Add TCEP to final concentration of 10 mM and incubate samples at 60°C for 60 minutes.

-

5

Add Iodoacetamide solution to final concentration of 12 mM, and incubate at room temperature (20°C) in the dark for 30 minutes.

CRITICAL STEP: Denature proteins to ensure complete digestion of proteins to peptides.

-

6

Dilute proteins with phosphate buffer to reduce the urea concentration to less than 2 M and save ~1 µg of protein to check on SDS-PAGE.

-

7

Add 20 µg of trypsin and digest samples at 37°C for 4 hours with gentle shaking.

PAUSE POINT Digestion can be left overnight at 37°C.

-

8

Remove undigested materials by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 minutes.

-

9

Analyze ~1 µg of peptides after digestion and the saved ~1 µg of protein from step 5 by SDS-PAGE to check the degree of completion of tryptic digestion.

CRITICAL STEP: Digest proteins completely for high specificity and yield of glycopeptide.

If digestion is not complete, another batch of enzyme can be added, and digest samples for additional 4 hours at 37°C.

PAUSE POINT: Digested peptides can be stored frozen at −20°C for several weeks.

TROUBLESHOOTING:

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of extraction of N-linked glycopeptides from a variety of biological samples followed by SPEG.

Coupling of glycopeptides to solid support

-

10

Add 10 µl of 5 N HCl to digested peptides (Check pH ≤3).

-

11

Condition C18 SepPak column by washing C18 column twice with 1ml of 0.1 % TFA in 50% ACN, then twice with 1 ml 0.1% TFA.

-

12

Load the sample onto the conditioned C18 SepPak column.

-

13

Wash the C18 SepPak column three times with 1 ml of 0.1% TFA, and elute the peptides twice with 0.2 ml of 0.1% TFA in 50% ACN.

-

14

Add 45 µl of sodium periodate to each sample. Incubate samples in dark at 4°C for 1 hour (10 mM final sodium periodate concentration).

-

15

Add 3.6 ml of 0.1% TFA to the sample.

-

16

Condition C18 SepPak column by washing C18 column twice with 1 ml of 0.1% TFA in 50% ACN, then twice with 1 ml 0.1% TFA.

-

17

Load the sample onto the conditioned C18 SepPak column.

-

18

Wash the C18 SepPak column three times with 0.1% TFA, and elute the peptides twice with 0.2 ml of 80% ACN with 0.1% TFA.

-

19

Prepare 25 µl of pure hydrazide resin (50 µl of 50% slurry) per sample, spin the resin briefly (3,000 rpm for 30 seconds) and remove the solution from the resin. Wash hydrazide resin by re suspending the resin in 1 ml of de-ionized water and removing water after brief spinning.

-

20

Add the plasma peptides to the hydrazide resin and conjugate the glycopeptides at room temperature by mixing for a minimum of 3 hours.

PAUSE POINT: Coupling can be left overnight at room temperature and immobilized glycopeptides on solid support can be store at 4°C for up to a month.

Labeling of N-linked glycopeptides with stable isotope tags

-

21

To detect quantitative changes of N-linked glycopeptides from two biological samples using isotopic labeling and mass spectrometry, wash the resin three times each with 800 µl of 1.5 M NaCl, water, and DMF/pyridine/H2O=50/10/40 (v/v/v). Remove supernatant by spinning at 2500g for 5 minutes at each wash.

-

22

Resuspend the resin in 25 µl of DMF/pyridine/H2O=50/10/40 (v/v/v) and spike in 1 µl of a standard peptide with a free α-amino group (Angiotensin I peptide) and 1 µl of standard peptide with a free ε-amino group in lysine (Neurotensin peptide).

-

23

Add light (d0) succinic anhydride solution to one biological sample and heavy (d4) isotope labeled succinic anhydride solution to the second of the two samples being compared. The final concentration of succinic anhydride is 100 mM, and the samples are incubated at room temperature (20°C) for or 1 hour.

CRITICAL STEP: Check the completion of peptide labeling by monitoring the mass shift of the standard peptide by mass spectrometry. Complete conversion of standard peptides to modified peptides (100 mass unit addition for labeling with light succinic anhydride and 104 mass unit addition for labeling with heavy succinic anhydride) is expected for complete labeling reactions. If necessary, incubate samples for another hour with an additional aliquot of succinic anhydride solution.

Releasing formerly N-glycosites from solid support

-

24

Wash the resin three times each with 800 µl of DMF, water, and ammonium bicarbonate buffer. Remove supernatant by spinning at 2500g for 5 minutes at each step.

-

25

Resuspend the resin in 25 µl ammonium biocarbonate buffer, add 3 µl of PNGase F (500 units/µl) and incubate at 37°C for 4 hours with mixing.

-

26

Transfer the supernatant to a glass vial and wash the hydrazide resin twice with 100 µl of ammonium bicarbonate buffer.

-

27

Combine the washes with the supernatant and purify the peptides with C18 SepPak column as described from step 9 to 12.

-

28

Dry the released glycopeptides in the glass vial within a SpeedVac in room temperature (20°C) until complete dryness.

-

29

Dissolve peptides in 20 µl of 0.4% acetic acid for mass spectrometry analysis (5 µl can be used in each analysis).

PAUSE POINT: Released peptides can be stored at −20°C.

Identification of peptides by mass spectrometry

-

30

Analyze peptides using LCQ or LTQ ion-trap mass spectrometer or ESI quadrupole-time-of-flight (qTOF) mass spectrometer according to standard practices and manufacturers’ instructions6.

-

31

Search MS/MS spectra against a human protein database using the SEQUEST software 21. The database search parameters are set to the following modifications: carboxymethylated cysteines, oxidized methionines, succinic anhydride modified amino-termini and lysines, and a (PNGase F-catalyzed) conversion of Asn to Asp that occurs at the original site of carbohydrate attachment to the peptide/protein (i.e. the N-glycosite). No other constraints are included for database searches.

-

32

Statistically analyze database search results using PeptideProphet, which effectively computes a probability for the likelihood of each identification being correct (on a scale of 0 to 1) in a data-dependent fashion 22. A PeptideProphet probability score of ≥0.9 is used as a filter to remove low probability peptide identifications. Since it is known that the majority of N-linked glycosylation occurs at a consensus N-X-S/T sequon (where X is any amino acid except proline) 9, the assigned peptide sequences from step 30 are additionally filtered to remove non-motif-containing peptides. Finally, peptide sequences are analyzed with respect to individual unique N-X-S/T sequons such that overlapping sequences containing the same N-X-S/T sequon (i.e. redundant N-linked glycopeptides for the same N-glycosite) are resolved in favor of those peptide sequences that contained the greater number of tryptic cleavage termini.

See TROUBLESHOOTING

TIMING

Steps 1–8: 1 day

Steps 9–19: 1 day

Step 20–28: 1 day

Step 29–31: 1 day

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

To illustrate the protocol, glycopeptides from 1 mg of proteins from tissues and plasma were isolated, and ~10 µg of total N-linked glycopeptides were recovered. Such isolated peptides were analyzed by LTQ and MS/MS spectra were searched against protein database using SEQUEST. The analysis resulted in over 1000 peptide identifications that contain the consensus N-linked glycosylation motif (N-X-T/S motif, X can be any amino acids except P) and have a PeptideProphet score of at least 0.9 6. The identified glycopeptides represent over 300 individual, unique N-X-S/T sequons after overlapping sequences containing the same N-X-S/T sequon are resolved. The specificity of the identified peptides is over 90%, as calculated by the percentage of identified peptides containing consensus N-linked glycosylation motif.

Among about 300 peptides identified from the mixed samples, 28 peptides were detected and quantified in both tissue and plasma. These results indicate that the method can selectively isolate N-glycosites from mixtures of glycoproteins.

An example of quantitative analysis of glycopeptides with isotopic labeling is shown in Figure 3 6. Glycopeptides immobilized on hydrazide resin from two samples were labeled with light (d0) or heavy (d4) forms of succinic anhydride. After labeling, the beads containing the two samples were combined and the formerly N-glycosites were released. The combined samples were analyzed by LC-MS using ESI-qTOF. The quantification is illustrated for a single scan of the mass spectrometer in MS mode. The paired peptide is doublely charged and has a mass difference of four units with monoisotopic peaks at 629.88 and 631.86 (Fig. 3). The peptide was sequenced by MS/MS analysis using ESI-qTOF and identified by database searching 21. It was identified with peptide sequence EEQFN#STFR from human Ig γ-1 chain C region secreted form, a classic serum protein. This shows that accurate quantification of relative glycopeptide abundance from two samples can be achieved with stable isotope tagging.

Figure 3.

Accurate quantification of N-glycosites using isotopic labeling of N-termini.

Table 1.

Troubleshooting

| PROBLEM | POSSIBLE REASON | SOLUTION |

|---|---|---|

| Step 9: Incomplete trypsin digestion |

|

|

| Step 32: None or few glycopeptides identified |

|

|

| Step 32: Low specificity, identified peptides containing high percentage of non-glycopeptides |

|

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, by grant R21-CA-114852 (to H.Z.) and by Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract No. N01-HV-8179 (to R. A.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Spiro RG. Protein glycosylation: nature, distribution, enzymatic formation, and disease implications of glycopeptide bonds. Glycobiology. 2002;12:43R–56R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/12.4.43r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durand G, Seta N. Protein glycosylation and diseases: blood and urinary oligosaccharides as markers for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Clin Chem. 2000;46:795–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeze HH. Update and perspectives on congenital disorders of glycosylation. Glycobiology. 2001;11:129R–143R. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaji H, et al. Lectin affinity capture, isotope-coded tagging and mass spectrometry to identify N-linked glycoproteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:667–672. doi: 10.1038/nbt829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Li XJ, Martin DB, Aebersold R. Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:660–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, et al. High throughput quantitative analysis of serum proteins using glycopeptide capture and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:144–155. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400090-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:845–867. doi: 10.1074/mcp.r200007-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth J. Protein N-glycosylation along the secretory pathway: relationship to organelle topography and function, protein quality control, and cell interactions. Chem Rev. 2002;102:285–303. doi: 10.1021/cr000423j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bause E. Structural requirements of N-glycosylation of proteins. Studies with proline peptides as conformational probes. Biochem J. 1983;209:331–336. doi: 10.1042/bj2090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, et al. UniPep, a database for human N-linked glycosites: A Resource for Biomarker Discovery. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R73. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-8-r73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutsch EW, et al. Human Plasma PeptideAtlas. Proteomics. 2005;5:3497–3500. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li XJ, et al. A software suite for the generation and comparison of Peptide arrays from sets of data collected by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1328–1340. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500141-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, et al. Human plasma N-glycoproteome analysis by immunoaffinity subtraction, hydrazide chemistry, and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:2070–2080. doi: 10.1021/pr0502065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran P, et al. Identification of N-linked glycoproteins in human saliva by glycoprotein capture and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1493–1503. doi: 10.1021/pr050492k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan S, et al. Identification of glycoproteins in human cerebrospinal fluid with a complementary proteomic approach. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2769–2779. doi: 10.1021/pr060251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, et al. Mass spectrometric detection of tissue proteins in plasma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:64–71. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600160-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewandrowski U, Moebius J, Walter U, Sickmann A. Elucidation of N-glycosylation sites on human platelet proteins: a glycoproteomic approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:226–233. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500324-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu AY, Zhang H, Sorensen CM, Diamond DL. Analysis of prostate cancer by proteomics using tissue specimens. J Urol. 2005;173:73–78. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146543.33543.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gygi SP, et al. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:994–999. doi: 10.1038/13690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aebi M, Hennet T. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: genetic model systems lead the way. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eng J, McCormack AL, Yates JR., 3rd An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]