Abstract

Background: Polyglycolic acid mesh (PAM) reinforcement of colonic anastomoses were evaluated. Methods: Twenty female albino rabbits were divided into two groups. Each rabbit underwent segmental colonic resection with single-layer anastomosis. In one group of rabbits, PAM of length equal to the circumference of the anastomosis was applied. Rabbits were sacrificed on postoperative day 10 and peritoneal adhesions, anastomosis burst pressure, and anastomosis histopathological characteristics were evaluated. Results: The average burst pressure for the control and PAM groups was 149±15.95 mmHgand 224±124.5 mmHg, respectively (p=0.578). All control anastomoses burst, whereas only five (50%) PAM anastomoses burst (p<0.03). There was no anastomotic leakage in the control group, whereas three PAM group anastomoses leaked (p=0.210). The collagen fiber density and amount of neovascularization were lower in the PAM than the control group (p=0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). The average peritoneal adhesion value was 1.6±0.51 in the control group and 2.9±0.31 in the PAM group (p<0.0001). Conclusion: The new fixed PAM-reinforced anastomosis technique resulted in an increased risk of anastomosis leakage and peritoneal adhesion, but also higher in non-burst anastomoses.

Keywords: Anastomosis, polyglycolic acid, colon, mesh, novel, technique

Introduction

Various techniques, materials, and devices are used in intestinal anastomosis [1]. The aim of these procedures is to prevent/reduce anastomosis complications, but such complications continue to occur. More than half of all postoperative deaths are caused by sepsis associated with anastomotic leakage [2,3]. The three major complications of intestinal anastomosis are leakage, bleeding, and stenosis. Of these, leakage is the most severe and common complication, and is associated with the highest mortality rate [4]. A multi-center study reported that the frequency of leakage from anastomoses following colonic resection was 0.5-30% [5]. The frequency of complications increases progressively from the ligament of Treitz to the distal end of the colon. For example, the risk of leakage after proximal anastomosis in the small intestine is 1%, but can be as high as 16% after low anterior colonic resections [6,7]. The frequency of asymptomatic leakage, which cannot be clinically or radiologically identified, is unknown, although such leakage is thought to occur two-to-three times more frequently than symptomatic leakage [8,9].

The present study investigated the use of a new technique for preventing anastomosis leakage. Rabbits underwent a single-layer standard anastomosis to the proximal colon after segmental resection. The new technique involved complete coverage of the anastomotic contour with a fixed polyglycolic acid mesh (PAM) to provide external mechanical support.

Methods

This study was performed at the Experimental Animal Production and Research Laboratory of Cerrahpasa Medical School, Istanbul University, and was approved by the local Animals Ethics Committee. All protocols were in accordance with the regulations governing the care and use of laboratory animals in the declaration of Helsinki.

Twenty female New Zealand white rabbits were used (mean weight, 2800±50 g; mean age, 6 months; outbred). The rabbits were housed singly in standard cages with stainless steel tops and bottoms and woven wire sides. Cage floors were covered with wood shavings that were changed daily. Rabbits were kept at room temperature and with adequate ventilation. Water and feeding containers were made of standard plastic, with side entrances. Animals were fed on pellets designed for small laboratory animals.

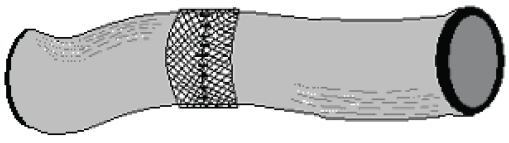

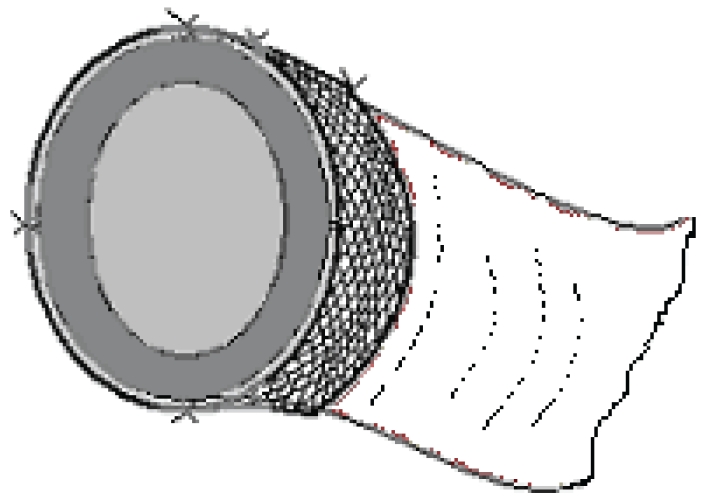

Rabbits were starved overnight and anesthetized with Ketamine (Ketalarâ, Parke Davis and Co. Inc.; 40 mg/kg body weight) and Xylazin (Rompunâ Bayer Co.; 5 mg/kg body weight). The anterior abdominal wall was shaved and sterilized with povidone iodine. A 6-cm mid-line incision was made at the inferior abdomen. A 4-cm segment of the proximal colon was resected 2 cm distal to the cecum. In the control group, a single-layer anastomosis was made using a 3/0 polypropylene suture (Prolene®, Kurtsan A.S.) and the fascia and skin were closed separately with 2/0 polypropylene sutures using a continuous suturing technique. In the PAM group, anastomoses were made as in the control group except that approximately 5-cm lengths of suture were left intact at anastomosis sites on the mid-line of the anterior mesenteric side, the mid-line of both lateral sides, and on both sides of the mesentery. Each anastomosis was covered with a 15 nm-pore-sized PAM (Vicryl Mesh®; Eticon Co.) patch of width 2 cm and of length equal to the circumference of the anastomosis. The mesh was placed such that the anastomotic contour was situated in the middle. The suture ends were passed through openings proximate to that area of mesh and tied together to fix the anastomosis at these regions (Figure 1). Sutures were passed through the ends of the free margins of the mesh proximate to the mesenteric margin, and next passed through the mesentery. At this point the angle of the lamp illuminating the surgical table was changed to provide trans-illumination, and great care was taken to ensure that the suture passing through the colonic mesentery did not damage the mesenteric vessels (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mesh covered colonic anastomosis (anterior view).

Figure 2.

Mesh covered colonic anastomosis (trans-sectional view).

After examination at 12 h postoperatively, the rabbits were allowed their usual feed. Animals were sacrificed on postoperative day 10 by in-traperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg sodium pentothal. To expose the entire peritoneal cavity, an inverted “u” incision was made on the anterior abdominal wall. Adhesions in the peritoneal cavity were classified according to the Evans Model [10] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adhesion grading according to Evans Model

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0 | No adhesions |

| 1 | Spontaneously separating adhesions |

| 2 | Adhesions separating by traction |

| 3 | Adhesions separating by dissection |

In the control group, the anastomotic contour was resected together with 5-cm proximal and distal borders. In the PAM group, the resection border was 5 cm from the margins of the mesh. The distal ends of all resected intestinal segments were tightly tied with 0 no polypropylene sutures (Prolen®). To measure intraluminal pressure in mmHg, a plastic catheter with a diameter of 18F was inserted into the lumen from the proximal end, and the other end of the catheter was tied parallel to a transducer (Alp-K2 SphygmomanometerÒ, Norticon Co.) and an air pump. The intestinal segment was immersed in a glass vessel containing water, and air was applied to the lumen at a speed of 2 mL/min. The first outlet of air from the anastomotic contour was defined as the burst pressure of the anastomosis. In the PAM group, when the first air eruption was from intact intestinal segments outside the anastomotic contour and/or outside the area covered with mesh (i.e., non-sutured and/or not covered with mesh and/or not neighboring the mesh), and not accompanied by air eruption from the anastomotic contour, the condition was recorded as a “non-burst anastomosis". The equipment used to measure burst pressure had a maximum pressure reading of 340 mmHg, and this value was used in statistical analysis for non-burst anastomoses.

Following the burst test, each anastomotic contour, with 0.5 cm borders, was cut out and placed in formol for histopathological investigation. Specimens were fixed in 70% (v/v) alcohol, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were cut at a thickness of 5 mm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Each contour was histopathologically classified according to the Ehrlich-Hunt model [11]. The tissue was evaluated in terms of quantity of inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, neovascularization level, and collagen content (Table 2).

Table 2.

Erlich-Hunt Model

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| Grade-0 | No |

| Grade-1 | Low density and seperated |

| Grade-2 | Low density and in all places |

| Grade-3 | High density but seperated |

| Grade-4 | High density and in all places |

The primary evaluation criteria were anastomotic burst pressure and leakage, and the secondary criteria were histopathological findings and number of peritoneal adhesions.

Results

In the control group, the burst pressure mean, median, and range were 149±15.95, 150, and 40-160 mmHg, respectively. In the PAM group, the burst pressure mean, median, and range were 224±124.5, 245, and 90-340 mmHg, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of mean burst pressure (MW: 42, p=0.578). All control anastomoses burst, whereas only five (50%) PAM anastomoses burst (p<0.03). There was no anastomotic leakage in the control group, but three PAM group anastomoses leaked (p=0.210). The risk of anastomosis leakage was 9.8-fold higher in the PAM group but also the probability of non-burst anastomosis was 21-fold higher in the PAM group than the control group.

Histological analysis showed that greater inflammatory cell infiltration in the PAM group compared to the control group (p=0.047), whereas fibroblast activation was similar in both groups (p=0.361). Neovascularization and collagen fiber ratios were lower in the PAM group than in the control group (p=0001 and p=0.002, respectively) (Table 3). The mean peritoneal adhesion grades were 2.9±0.31 in the PAM group and 1.6±0.51 in the control group (MW: 3, p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Histopathologic evaluation results

| Grades | Control Group | PAM Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Inflamation | 1 | 1 | 10% | 0 | 0% | |

| 2 | 8 | 80% | 3 | 30% | ||

| 3 | 1 | 10% | 5 | 50% | χ2:7,93 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 20% | p=0,047 | |

| Fibroblast activation | 1 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |

| 2 | 7 | 70% | 5 | 50% | ||

| 3 | 3 | 30% | 5 | 50% | χ2:0,83 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | p=0,361 | |

| Neovaskularization | 1 | 0 | 0% | 8 | 80% | |

| 2 | 6 | 60% | 2 | 20% | ||

| 3 | 4 | 40% | 0 | 0% | χ2:14 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | p=0,001 | |

| Collagen Deposition | 1 | 0 | 0% | 8 | 80% | |

| 2 | 4 | 40% | 2 | 20% | ||

| 3 | 4 | 40% | 0 | 0% | χ2:14,6 | |

| 4 | 2 | 20% | 0 | 0% | p=0,002 | |

Discussion

Leakage is the most lethal anastomosis complication [2-4]. A number of external anastomosis reinforcements have been tested, including peritoneal graft, omental graft, dura mater, and meshes (Dacron, Marlex, polypropylene) [12-20]. Omentum is the tissue most often used for gastrointestinal anastomosis reinforcement. Several studies suggested that omental reinforcement prevents anastomosis leakage [12-15], whereas others found that this approach caused an increased risk of infection associated with pedicular necrosis or late intestinal obstruction [16,17]. Gulati and colleagues compared Dacron and Marlex meshes with free omental and peritoneal coverings, and found that the meshes were more effective than the coverings [18]. Eryilmaz and associates reported that dura mater and free peritoneal graft reinforcement of anastomoses was not effective [19]. In the rabbit colonic anastomosis model, Aysan and associates used polypropylene mesh reinforcement and found high anastomosis burst pressures within a short observation period [20].

Non-absorbable meshes reinforce anastomoses permanently, and are thus associated with higher burst pressures and fewer burst anastomoses than absorbable meshes [20]. However, non-absorbable meshes may increase the risk of peritoneal adhesion, anastomotic stenosis, and colon perforation, in the longterm.

We used PAM in the present study as we believe that use of absorbable mesh reduces the risk of peritoneal adhesion formation and provide reinforcement for a number of days prior to becoming totally absorbed. Few studies have appeared regarding the use of PAM for anastomosis reinforcement. Dilek and colleagues evaluated outcomes following large bowel anastomoses reinforced with PAM and peritoneal grafts in a septic environment. The cited authors found that the rates of anastomotic leakage, moderate anastomotic stenosis, and reoperation for severe anastomotic stenosis, were 8%, 33% and 16%, respectively [21]. In rat studies, Henne and associates and Kreischer and colleagues examined PAM-reinforced colonic anastomoses and found lower burst pressures in a PAM compared to a control group [22,23].

In the above PAM studies, the anastomoses were merely covered with mesh. However, strong peristaltic colon movements can cause mesh dehiscence or migration from anastomotic surfaces. In the present study, the mesh was fixed to the anastomoses using extended suture ends. Fixing did not involve suturing to the intestinal wall. This is a new technique, and, in our opinion, mesh fixation is very important for external reinforcement of the anastomosis. Fixation ensures the mesh does not migrate, and also ensures precise reinforcement with no gap between the mesh and the anastomosis.

The present study found that PAM reinforcement resulted in higher burst pressures, but a 9.8-fold higher risk of leakage, compared to controls. These findings may be explained by the histopathological results. In the PAM group, inflammation was high but collagen fiber density and neovascularization were low compared to the control group. The high density of inflammatory cells may reflect a foreign body reaction to the mesh (the pore size was only 15 nm), and chemical reactions during the absorption process. The low collagen fiber density and low neovascularization in the PAM group may reflect reduced healing processes, with the recovery of colonic anastomosis being directly related to the level of collagenous tissue deposition [25]. The PAM group showed a higher level of peritoneal adhesion, and this was most likely related to the presence of the mesh as peritoneal adhesion formation is associated with foreign bodies in the peritoneal cavity [24].

The burst pressure of an anastomosis indicates the resistance of the anastomotic contour to intra-luminal pressure. The anastomosis burst pressure is directly related to the amount of mature connective tissue formed by collagenous tissue deposition [26,27]. The absence of burst may be attributed to the external mechanical support provided by the mesh. Thus, the mechanical support provided by mesh may be most important in preventing leakage.

The new fixed PAM reinforced anastomosis technique described here was associated with an increased risk of anastomosis leakage and peritoneal adhesion formation, but also a higher burst pressure and statistically significant non-burst anastomoses. We are currently examining ways to reduce the anastomotic leakage and peritoneal adhesions associated with this procedure. We plan to produce a knitted net from 3/0 polyglycolic acid surgical rope (Katsan Co., PCA CerrahiSutur®, 75cm) to create a mesh with 3 mm pore diameter so that the lower mesh mass may reduce both the level of foreign body reaction and the amount of chemical reactions occurring duringthe absorption period.

References

- 1.McCue JL, Philips RKS. Sutureless intestinal anastomoses. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard JD, Nicholson ML, Sayers RD, Lloyd D, Everson NW. Intraoperative air testing of colorectal anastomoses: a prospective, randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1095–1097. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen O, Schwenk W, Hucke HP, Stock W. Colorectal stapled anastomoses. Experiences and results. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:30–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02048265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jex RK, Van Heerden JA, Wolff BG, Ready RL, Ilstrup DM. Gastrointestinal anastomoses. Ann Surg. 1987;206:138–141. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198708000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fielding LP, Stewart-Brown S, Bleosovski L, Kearney G. Anastomotic integriity after operations for large bowel cancer: a multicenter study. Br Med J. 1980;28:411–414. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6237.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson ML, Beard JD, Horrocks M. Intraoperative inflow resistance measurement: a predictor of steal syndromes following femorofemoral bypass grafting. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1064–1066. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800751106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignali A, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Church JM, Hull TL, Strong SA, Oakley JR. Factors associated with the occurrence of leaks in stapled rectal anastomoses: a review of 1,014 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bokey EL, Chapuis PH, Fung C, Hughes WJ, Koorey SG, Brewer D, Newland RC. Postoperative morbidity and mortality following resection of the colon and rectum for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:480–486. doi: 10.1007/BF02148847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGinn FP, Gartell PC, Clifford PC, Brunton FJ. Staples or sutures for low colorectal anastomoses: a prospective randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1985;72:603–605. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans DM, Mc Aree K, Guyton DP, et al. Dose dependency and wound healing aspects of the use of tissue plasminogen activator in the prevention of intra-abdominal adhesions. Am J Surg. 1993;165:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80516-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrlich HP, Hunt TK. The effects of cortisone and anabolic steroids on the tensile strength of healing wounds. Ann Surg. 1969;170:203–206. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196908000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLachlin AD, Denton DW. Omental protection of intestinal anastomoses. Am J Surg. 1973;125:134–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(73)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsmith HS. Protection of low rectal anastomosis with intact omentum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;144:585–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsikas D, Sechas M, Antypas G, et al. Beneficial effects of omentalwrapping of unsafe intestinal anastomoses. An experimenatl study. Int Surg. 1977;62:435–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg BM, Low D, Rosato EF. The use of omental grafts in operations performed upon the colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161:487–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John H, Buchmann P. Improved perineal wound healing with the omental pedicle graft after rectal excision. Colorectal Dis. 1991;6:193–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00341389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fergusson CM. Use of omental pedicle grafts in abdominoperineal resection. Am Surg. 1990;56:310–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulati SM, Thusoo TK, Kakar A, Iyenger B, Pandey KK. Comparative study of free omental, peritoneal, Dacron velour, and Marlex mesh reinforcement of large-bowel anastomosis: an experimental study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:517–521. doi: 10.1007/BF02564157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eryilmaz R, Samuk M, Tortum OB, Akcakaya A, Sahin M, Goksel S. The role of dura mater and free peritoneal graft in the reinforcement of colon anastomosis. J Invest Surg. 2007;20:15–21. doi: 10.1080/08941930601126108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aysan E, Dincel O, Bektas H, Alkan M. Polypropylene mesh covered colonic A novel colonic anastomosis technique anastomosis. Results of a new anastomosis technique. Int J Surg. 2008;6:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dilek ON, Bakir B, Dilek FH, Demirel H, Yiğit MF. Protection of intestinal anastomoses in septic environment with peritoneal graft and polyglycolic acid mesh: an experimental study. Acta Chir Belg. 1996;96:261–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henne-Bruns D, Kreischer HP, Schmiegelow P, Kremer B. Reinforcement of colon anastomoses with polyglycolic acid mesh: an experimental study. Eur Surg Res. 1990;22:224–230. doi: 10.1159/000129105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreischer HP, Henne-Bruns D, Schmiegelow P, Kremer B. Securing colon anastomoses by surrounding it with a polyglycolic acid filament net. An animal experiment study. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1990;375:200–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00187438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang ZL, Xu SW, Zhou XL. Preventive effects of chitosan on peritoneal adhesion in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(28):4572–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law NW, Ellis H. Adhesion formation and peritoneal healing on prosthetic materials. Clinical Materials. 1988;3:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbott RE, Corral CJ, Maclvor DM, et al. Augmented inflammatory responses and altered wound healing in cathepsin G deficient mice. Arch Surg. 1998;133:1002–1005. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.9.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albertson S, Hummel RP, Breden M, Greenhalgh DG. PDGF and FGF reverse the healing impairment in protein malnourished diabetic mice. Surgery. 1993;114:368–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]