Abstract

Motivation: Several international collaborations and local projects are producing extensive catalogues of genomic variations that are supplementing existing collections such as the OMIM catalogue. The flood of this type of data will keep increasing and, especially, it will be relevant to a wider user base, including not only molecular biologists, geneticists and bioinformaticians, but also clinical researchers. Mapping the observed variations, sometimes only described at the amino acid level, on a genome, identifying whether they affect a gene and—if so—whether they also affect different isoforms of the same gene, is a time consuming and often frustrating task.

Results: The PICMI server is an easy to use tool for quickly mapping one or more amino acid or nucleotide variations on a genome and its products, including alternatively spliced isoforms.

Availability: The server is available at www.biocomputing.it/picmi

Contact: anna.tramontano@uniromal.it

1 INTRODUCTION

The availability of novel high-throughput technologies for identifying variations, both pathological and physiological, in sequenced genomes is producing a wealth of data that is readily available to researchers.

These data will continue to be produced at an unprecedented speed not only in projects based on large international collaborations, but also in individual labs and will add to existing collections such as OMIM (Amberger et al., 2009), SwissProt (The UniProt Consortium, 2010) and the related mutation portal SwissVar (Mottaz et al., 2010).

It can be easily foreseen not only that more and more data will be available, but also that the scientists who will need to access and analyze them will not be limited to molecular biologists, geneticists and bioinformaticians, as it has been mostly the case so far, but will include clinical researchers and in the future also medical doctors. This implies that tools to easily access and interpret these data should be provided to the community and that they have to be simple, reliable and user-friendly.

Given one or more variations of interest, one needs to map them back to the corresponding genome, verify in which region they fall and, if they map to a coding region, understand whether they affect, and in which way, one or more of the isoforms of the gene. This task is not made easier by the fact that the version of the genome might have changed since the time of identification of the mutation.

Less straightforward is the analysis of an amino acid mutation when the corresponding nucleotide variation is not reported, as is the case for several instances in OMIM (Amberger et al., 2009) and for those in the SwissVar collection (Mottaz et al., 2010).

At present, Ensembl (Hubbard et al., 2009) can be used to retrieve the location of nucleotide variations, by installing the relevant APIs and locally running a perl script. Associated web-based tools such as the one described in McLaren et al. (2010) can perform the mapping of nucleotide variations, but not of amino acid variations. For the latter, the corresponding nucleotide variations can only be retrieved, for example using SIFT (Kumar et al., 2009), when they correspond to a known SNP, stored for example in dbSNP (Sherry et al., 2001).

To address this conceptually easy, but technically time consuming and often frustrating problem, we developed the PICMI (Perhaps I Can Map It) server.

The server can map nucleotide variations on the human, mouse, rat and chicken genomes (altogether accounting for more than three quarters of the annotated variations) and on their different versions, report in which region they map and, when they fall in a coding region, provide information on their location on all isoforms of the gene, if any. Notably, the user can also input one or more amino acid variations for proteins in the UniProt database. In this case the system maps them back to the genome and infers, whenever this can be done unambiguously, the corresponding nucleotide variations that are subsequently analysed as described above.

2 DESCRIPTION

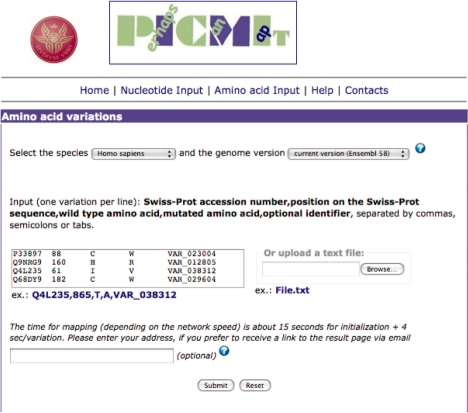

The server allows the selection of the relevant species and, if more than one genome assembly exists, of the specific version from Ensembl. Multiple nucleotide and amino acid variations can be used as input (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Input page of PICMI for amino acid variations.

Nucleotide variations are identified by their position on a chromosome and by the wild-type and mutated nucleotide. The server uses the information on the wild-type nucleotide to identify the correct strand and to verify that the selected base is indeed present in the correct position of the selected version of the specific genome. The VCF 1000 genome format can be selected as input as well by checking the appropriate box.

Unless the input position falls in an intergenic region, the tool will map it with respect to the transcript(s) and report whether it falls upstream, downstream, in the 5′ or 3′ untranslated region, in a stop-codon, in a skipped exon or in a coding exon. In the last case, the mutation is mapped on all the isoforms of the gene. The variation is assigned to the synonymous, nonsense or missense category and, in the latter case, the system provides the wild-type and mutated amino acid in each of the isoforms.

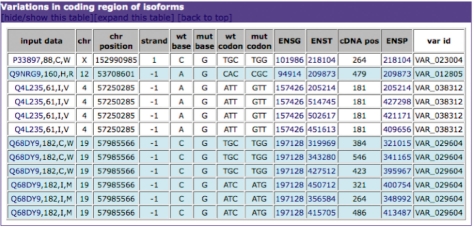

The user can also input one or more amino acid mutations in a given protein when the information on the corresponding nucleotide mutation is not available, as is the case for those reported in the SwissProt ‘Natural variant’ field, in the SwissVar portal and in a number of entries in OMIM. Given the UniProt identifier of the protein, the position of the mutation and the wild-type and mutated amino acid in the protein sequence, the system will retrieve the coordinates of the corresponding gene in the genome, identify the wild-type codon and verify whether the mutated amino acid can be unambiguously obtained by a single-nucleotide mutation. If this is the case, the identified nucleotide variation is treated as in the case of an input nucleotide variation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example of the output of PICMI for amino acid variations falling in a coding region.

The system relies on the Perl APIs provided by Ensembl. For nucleotide variations, it first verifies whether the input data are consistent with the genome sequence and, next, it maps the identified position on all the genes/isoforms spanning it. For amino acid variations, after a consistency check, it aligns the UniProt sequence to the corresponding Ensembl gene products and proceeds as in the case of nucleotide variations.

As an example of the usefulness of the amino acid variation option of the tool, entry 600509.0011 of the OMIM resource reports two mutations of the ABCC8 protein associated to hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, E1506K (Huopio et al., 2000) and E1507K (Pinney et al., 2008); however, the two mutations correspond to the same nucleotide variation, and the discrepancy in the numbering is due to the fact that they were originally mapped by the authors on different splicing isoforms of the protein.

The question obviously arises about how often an amino acid variation can be unambiguously assigned to a single nucleotide polymorphism. We tested the PICMI server on the whole collection of polymorphisms in the SwissVar knowledgebase that provides information on about 53 000 amino acid variations (release 56.8). (Results are available at www.biocomputing.it/picmi/SwissVar). Interestingly, >85% of the amino acid variations could be unambiguously associated to single nucleotide mutations and therefore mapped on all alternative isoforms of the corresponding analyzed genes.

3 CONCLUSIONS

We believe that this easy-to-use tool can reveal to be very useful both to simplify the mapping of nucleotide variations and, especially, to analyze a number of pathological and physiological variations at the nucleotide level when they are only reported at the protein level. In this way, the server can add value to existing amino acid variation data. We will continuously update it by adding more genomes, as soon as sufficient mutation data will accumulate. We also plan to allow mapping of insertions and deletions in the next release and to make the tool available as a web service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the Biocomputing group for useful discussions.

Funding: KAUST (Award N. KUK-I1-012-43) and FIRB (Italbionet and Proteomica).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Amberger J, et al. McKusick's online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D793–D796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard TJ, et al. Ensembl 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D690–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huopio H, et al. Dominantly inherited hyperinsulinism caused by a mutation in the sulfonylurea receptor type 1. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:897–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, et al. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protocols. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaz A, et al. Easy retrieval of single amino-acid polymorphisms and phenotype information using SwissVar. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:851–852. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinney SE, et al. Clinical characteristics and biochemical mechanisms of congenital hyperinsulinism associated with dominant KATP channel mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2877–2886. doi: 10.1172/JCI35414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry ST, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D142–D148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]