Abstract

Background

Ischemic cardiomyopathy is the major cause of heart failure and a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. The degree of left ventricular dysfunction in this setting is often out of proportion to the amount of overtly infarcted tissue and how decreased delivery of oxygen and nutrients leads to impaired contractility remains incompletely understood. The PHD prolyl hydroxylases are oxygen-sensitive enzymes that transduce changes in oxygen availability into changes in the stability of the HIF transcription factor, a master regulator of genes that promote survival in a low oxygen-environment.

Methods and Results

We found that cardiac-specific PHD inactivation causes ultrastructural, histological, and functional changes reminiscent of ischemic cardiomyopathy over time. Moreover, chronic expression of a stabilized HIFα variant in cardiomyocytes also led to dilated cardiomyopathy.

Conclusion

Sustained loss of PHD activity and subsequent HIF activation, as would occur in the setting of chronic ischemia, is sufficient to account for many of the changes in the hearts of individuals with chronic coronary artery disease.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, hibernation, hypoxia, ischemia, myocardium

Heart failure represents an enormous medical and societal burden affecting an estimated 5 million people in the United States alone 1. Over the last several decades, there has been a shift in the etiology for heart failure from valvular heart disease and hypertension to coronary artery disease. As a result, ischemic cardiomyopathy – symptomatic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction in the setting of coronary artery disease – now accounts for nearly 70% of all causes of heart failure in the United States 2. The exact molecular basis for ischemic cardiomyopathy remains uncertain. A better understanding of the molecular changes that occur in the ischemic myocardium, and animal models where this process can be studied, are needed.

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) plays a pivotal role in the transcriptional response to changes in oxygen availability at the cellular, tissue, and organismal level 3. HIF consists of a labile HIFα subunit, such as HIF1α or HIF2α, and a constitutively stable HIFβ subunit, such as HIF1β (also called ARNT1). When oxygen levels are low HIFα accumulates, dimerizes with HIFβ, and transcriptionally activates hundreds of genes that orchestrate cellular adaptation to hypoxia. When oxygen is present HIFα becomes hydroxylated on one (or both) of two conserved proline residues by members of the Prolyl Hydroxylase Domain (PHD, also called EglN) family 3. Once prolyl hydroxylated, HIFα is polyubiquitinated by a complex containing the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL), leading to its proteasomal degradation.

PHD enzymatic activity requires oxygen, reduced iron, and 2-oxoglutarate. In addition, these enzymes are sensitive to other inputs that indirectly reflect oxygen availability including changes in reactive oxygen species generated by the electron transport chain and changes in Krebs Cycle metabolites 3. Thus, the PHD proteins are poised to act as oxygen sensors, coupling changes in oxygen availability to changes in the HIF transcriptional program. As predicted, PHD function is compromised in ischemic myocardium as determined by increased accumulation of HIFα and HIF-responsive gene products 4–7.

Mammalian cells have three PHD paralogs: PHD1 (also called EglN2), PHD2 (EglN1), and PHD3 (EglN3). All three genes are widely expressed but there are organ-dependent differences in their expression. For example, both PHD2 and PHD3 are highly expressed in the heart. Although all three PHD family members can hydroxylate HIFα in vitro 8, 9, PHD2 appears to be the primary hydroxylase responsible for regulating HIFα levels in vivo, with PHD1 and PHD3 playing compensatory roles under certain conditions 10–13.

Recently, acute PHD2 inactivation in the heart using shRNA or siRNA was shown to be protective during acute cardiac ischemia in rodents 4, 14. This cardio-protective effect appears to be due to HIFα stabilization, adding to a growing number of reports where acute HIFα activation has been tissue protective in regional ischemia models 6, 15–19. Indeed, several PHD inhibitory drugs are now in development for this purpose. Nevertheless, the safety of chronic PHD inhibition or chronic HIFα activation remains unclear. This issue is important with respect to potential long term effects of such agents as well as to the possible sequelae of chronic HIFα activation in the setting of ischemic heart disease. An earlier attempt to study chronic HIFα activation in the heart utilized transgenic mice in which HIF-1α was under the control of α-myosin heavy chain (MHC) promoter6. These mice were grossly normal at baseline but sustained less tissue damage than littermate controls when subjected to experimental myocardial infarction. A caveat, however, is that the transgene encoded wild-type HIF-1α, which as described above, is rapidly degraded under normal oxygen conditions and, indeed, was undetectable in the non-ischemic transgenic hearts 6.

Recently, it was reported that cardiac-specific VHL deletion in mice caused cardiomyopathy, which was prevented by concomitant deletion of HIF-1α 20, 21. Although the latter observation established that HIF-1α was necessary for the observed phenotypes, it left open the question as to whether chronic HIF-1α would be sufficient to cause cardiomyopathy, especially as VHL has many functions that appear to be HIF and oxygen-independent 22, 23.

We reported the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in mice after systemic inactivation of PHD2, especially when combined with PHD3 loss 11, 13. However, these studies were potentially confounded because systemic PHD2 loss leads to massive polycythemia, which can cause volume overload and hyperviscosity syndrome. We therefore asked whether PHD inactivation, and subsequent HIF activation, has a cell-intrinsic effect on cardiomyocytes. Our findings suggest that sustained inactivation of PHD enzymes in the heart is sufficient to produce many of the hallmarks of ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Methods

Mice

The Phd2 flox/flox (F/F) mice used in these studies were described by us previously 11. Phd3−/− mice were a gift of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Tarrytown, NY). Vhl flox/flox (F/F) mice were a generous gift from Dr. Volker Haase (University of Pennsylvania) 24. The αMHC-Cre mice have been reported previously 25. All of these strains were backcrossed to C57BL/6 at least 5 times.

Phd2F/F mice and VhlF/F mice were crossed with αMHC-Cre mice to generate Phd2+/F; αMHC-Cre and Vhl+/F; αMHC-Cre, mice respectively. Phd2+/F; αMHC-Cre and Vhl+/F; αMHC-Cre were then crossed with Phd2+/F and Vhl+/F mice, respectively, to generate Phd2F/F;αMHC-Cre and VhlF/F;αMHC-Cre mice, respectively, as well as relevant littermate controls. Phd2F/F;αMHC-Cre mice were mated with Phd3−/− mice to generate Phd2+/F;Phd3+/−;αMHC-Cre mice. These mice were mated with Phd2+/F;Phd3+/− mice to generate Phd2F/F;Phd3+/+;αMHC-Cre mice, Phd2F/F;Phd3−/−;αMHC-Cre mice and relevant littermate controls. ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+ mice 26 were crossed with αMHC-Cre mice to generate ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+; αMHC-Cre mice.

Mice or cells were genotyped by PCR using the primers: Phd2 Fwd1 (for null allele); 5’-TCCATCCAGTCTGAGTTTCTTTCC-3’, Phd2 Fwd2 (for Wt and floxxed allele); 5’-AGATGACCTCCCCAACTCTGCTAC-3’, Phd2 Rev (Common primer); 5’-CAGTGTTCTGCCTCCATTTAT-3’. Phd3 Fwd1 (for Wt allele); 5’-GCCGGTAGACCAATGGGAG-3’, Phd3 Rev1 (for Wt allele); 5’-TCGTCAGACAGTCCCTTCAC-3’, Phd3 Fwd2 (for null allele); 5’-GAGTTTCGAGCAACTTTCCC-3’, Phd3 Rev2 (for null allele); 5’-GTCTGTCCTAGCTTCCTCACTG-3’.

Western Blot Analysis

Mouse tissue fragments (~ 50 µl) were homogenized in a 500 µl ice cold buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM KCl supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), 1mM Sodium Orthovanadate, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 0.4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (P-7626; Sigma-Aldrich) in 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes using a plastic pestle. The homogenates were centrifuged at 4500 × g for 5 minute at 4 °C. The resulting pellets were lysed with 8M Urea buffer containing 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6].

Equal amounts of protein extract, as determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline with 5% nonfat dry milk and probed with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF1α (NB100-479; Novus, Littleton, CO or AG10001; A&G Pharmaceuticals, Columbia, MD), rabbit polyclonal anti-HIF2α (NB100-122; Novus) or mouse monoclonal anti-vinculin (V9131; Sigma-Aldrich). Bound antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (31430/31432; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore).

mRNA Analysis

mRNA was purified with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNeasy column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). 0.5 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed (StrataScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and analyzed by real-time PCR using RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) and M×3005 thermocycler (Stratagene). Following primers were used for Ppargc1a Fwd; 5'-AACAGCAAAAGCCACAAAGACG -3', Ppargc1a Rev; 5'-GGGGTCAGAGGAAGAGATAAAGTTG -3', Ppargc1b Fwd; 5'-TTCAGATGGAACCCCAAGCGTC -3', Ppargc1b Rev; 5'-TCAGCACCTGGCACTCTACAATC -3',Ppara Fwd; 5'-CTGCCGTTTTCACAAGTGCC -3', Ppara Rev; 5'-CTTTCAGGTCGTGTTCACAGGTAAG -3', Pparg Fwd; 5'-CAAGAATACCAAAGTGCGATCAA -3', Pparg Rev; 5'-GAGCAGGGTCTTTTCAGAATAATAAG -3'. Primers for Pgk1, Vegfa, Phd2, Phd3 and Vhl were published before 11. Commercially available primers [QuantiTect Primers Assay (Qiagen)] were used for PAI-1 and Bnip3.

Echocardiography

Murine transthoracic echocardiography was performed on conscious mice using either a Vevo 770 or Vevo 2100 high resolution microultrasound system (Visualsonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada), as previously described 11.

Mouse Cardiac Surgery

Constriction of the transverse thoracic aorta was performed on age- and sex-matched mice as previously described 27. Briefly, mice were anesthetized, intubated, and placed on a respirator. Left medial thoracotomy was performed and the transverse aorta between the left common carotid artery and the right brachiocephalic artery was constricted with a 7.0 polypropylene suture tied against a 27G needle. The needle was withdrawn and the overlying skin was closed. Over the ensuing 8 weeks, serial echocardiography was performed at 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 8 weeks after TAC. After 8 weeks, the mice were sacrificed. Sections of the liver and lung were weighed both after dissection “wet,” as well as after incubation for 48 hours “dry.” The heart was weighed and normalized for body weight. The hearts were fixed and cut into 3 cross-sections of equal thickness from apex to base prior to histological analysis.

Permanent LAD ligations were performed as described previously 27.

Histological Analysis

All tissues were fixed with buffered 10% formalin solution (SF93-20; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Heart tissues were perfusion fixed. For standard hematoxylin and eosin staining, PAS staining or trichrome staining, tissues were embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning. For Oil Red O staining, fixed tissues were embedded in OCT compound (4583; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and then frozen for sectioning. Photomicrographs were obtained with Olympus BX51 microscope (40× objective lens and 10× eyepiece lens; total magnification, 200×), Q-Color5 digital camera and Q-Capture Suite acquisition software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Formalin-fixed sections were stained with FITC-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (Sigma-Aldrich) to outline cardiomyocytes and measure individual cardiomyocyte size.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were immunostained for HIF1α or HIF2α using the CSA II System (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and for CD34 using the EnVisionTM+ System (Dako), in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or 1mM EDTA (pH 8). Slides were then blocked with peroxide block, and then mouse block (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), followed by incubation with primary antibody (HIF1α, MS-1164-PABX, Neomarkers, dilution 1:5000; HIF2α (a mouse monoclonal clone UP15, raised against human HIF2α (amino acid 543~819), dilution 1:1000; CD34, AB8158, Abcam, dilution 1:100). For HIF1α and HIF2α staining, slides were then incubated with anti-mouse immunoglobulin secondary antibody for 15 minutes, fluorescyl-tyramide amplification reagent for 15 minutes, and anti-fluorescein-HRP for 15 minutes. For CD34 staining, slides were incubated with anti-rat immunoglobulin secondary antibody (Dako) for 30 minutes, followed by Envision anti-rabbit antibody for 30 minutes. Staining was developed using a DAB chromogen kit (Dako) and a light counterstaining with haematoxylin was used to reveal cells. Replacement of the primary antibody with PBS served as a negative control.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Hearts were fix perfused with ice cold buffer containing 2.5% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 0.1M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) (#15949; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Heart tissues from the endocardial aspect of the left ventricular wall were embedded for transmission electron microscopy (Tecnai™ G2 Spirit BioTWIN; FEI company, Hillsboro, OR) with a cooled CCD camera (XR41C; Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA) and Image Caption Engine acquisition software (Advanced Microscopy Techniques).

Mitochondrial DNA Measurement

Total DNA from hearts was isolated with Gentra Puregene buffer (#158906; Qiagen) supplemented with proteinase-K (#19133; Qiagen). The amount of mitochondrial DNA (mt-Co1) and nuclear DNA (Rn18s) were compared by real-time PCR using following primers: mt-Co1 Fwd; 5'-CTGAGCGGGAATAGTGGGTA-3', mt-Co1 Rev; 5'-TGGGGCTCCGATTATTAGTG-3', Rn18s Fwd; 5'-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3’, Rn18s Rev; 5'-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3’.

Human Autopsy Samples

Hearts were obtained at autopsy under a protocol approved by the Brigham and Women’s institutional review board (IRB). Case histories, including cardiac risk factors and results of echocardiography and cardiac catheterization, were reviewed independently by two of us (J.M. and R.P.). Patients deemed to have ischemic cardiomyopathy had diabetes, hypertension, evidence of coronary artery disease on catheterization, as well as known LV dysfunction.

Cardiomyocyte Isolation

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from 8 week old Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre or Phd2+/+;αMHC-Cre mice as previously described 28.

Measurement of O2 Consumption

Cells were grown in custom 24 well plates (Seahorse Bioscience). The rate of change of dissolved O2 in the media was measured using a Seahorse Bioscience instrument (model XF24) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At the indicated timepoint oligomycin was added (1µM) as a control.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons at a single time point were performed using the Student t-test. Changes in cardiac measures over time were assessed using a hierarchical repeated measures mixed model approach, with the impact of genotype on cardiac outcome over time tested through an interaction. Nominal p-values are reported; there is no adjustment for multiple testing.

Results

Cardiac-specific Inactivation of PHD2 in Mice

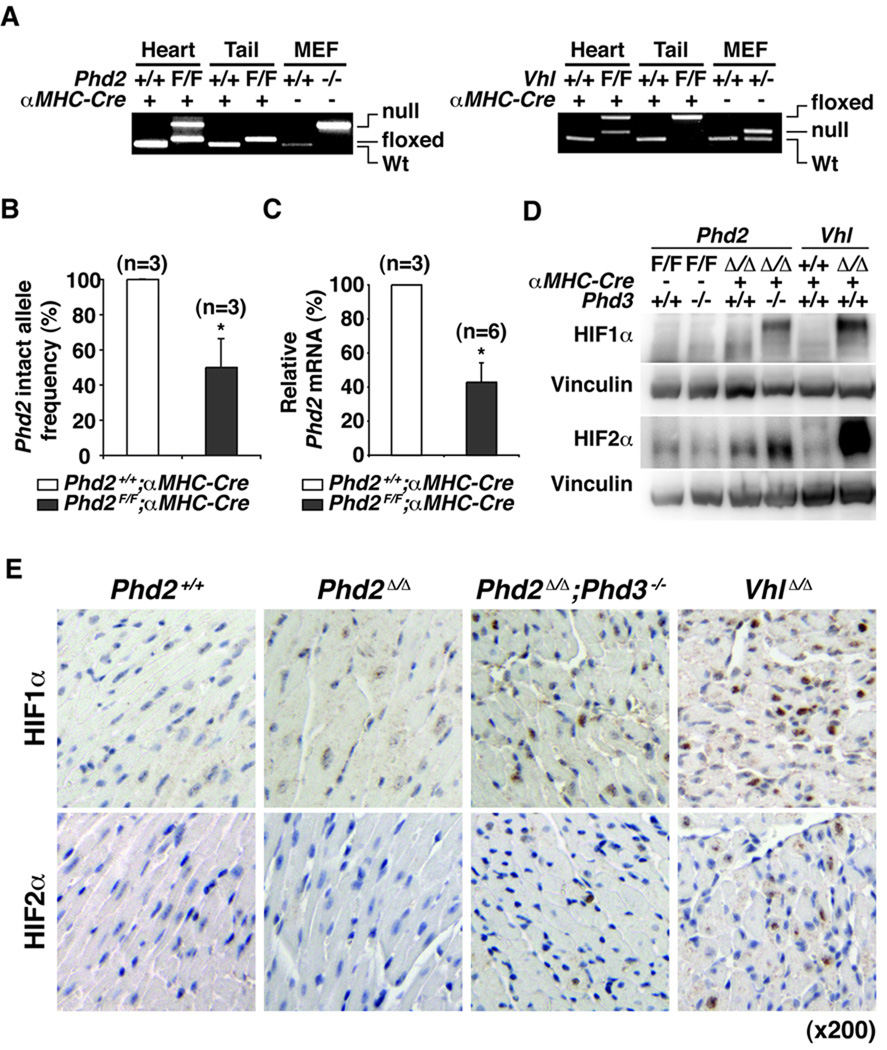

To ask whether cardiac dysfunction in the setting of systemic PHD2 inactivation is due, at least in part, to the loss of a cardiomyocyte-intrinsic PHD2 function, we crossed Phd2 flox/flox mice with mice that express Cre recombinase in cardiomyocytes under the control of the myosin heavy chain promoter (αMHC-Cre mice) 25. PCR-based genotyping confirmed effective recombination of the Phd2 locus in hearts, but not in tails, of Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice (Figure 1A and B). Incomplete recombination in the hearts probably reflects the presence of cells other than cardiomyocytes in the hearts. As expected, Phd2 mRNA levels were reduced in hearts from Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice compared to control, Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre, littermates (Figure 1C and Figure 2A).

Figure 1. Cardiac-specific PHD2 Inactivation.

A, PCR-based genotyping of PHD2 or VHL locus using genomic DNA (derived from hearts or tails) from mice with the indicated genotypes. MEFs with the indicated genotypes were used as controls. Incomplete recombination in the hearts probably reflects the presence of cells other than cardiomyocytes in hearts. (F=floxxed allele). B, PCR-based quantification of intact Phd2 allele frequency from mice with the indicated genotypes. *P<0.05. Error bars indicate 1 SD. C, Real-time PCR analysis for Phd2 mRNA in hearts from 5 week old mice with the indicated genotypes. *P<0.05. Error bars indicate 1 SD. D and E, Immunoblot (D) and immunohistochemical (E) analysis of hearts from 5 week old mice with the indicated genotypes. (Δ= null allele generated by recombination of floxxed allele).

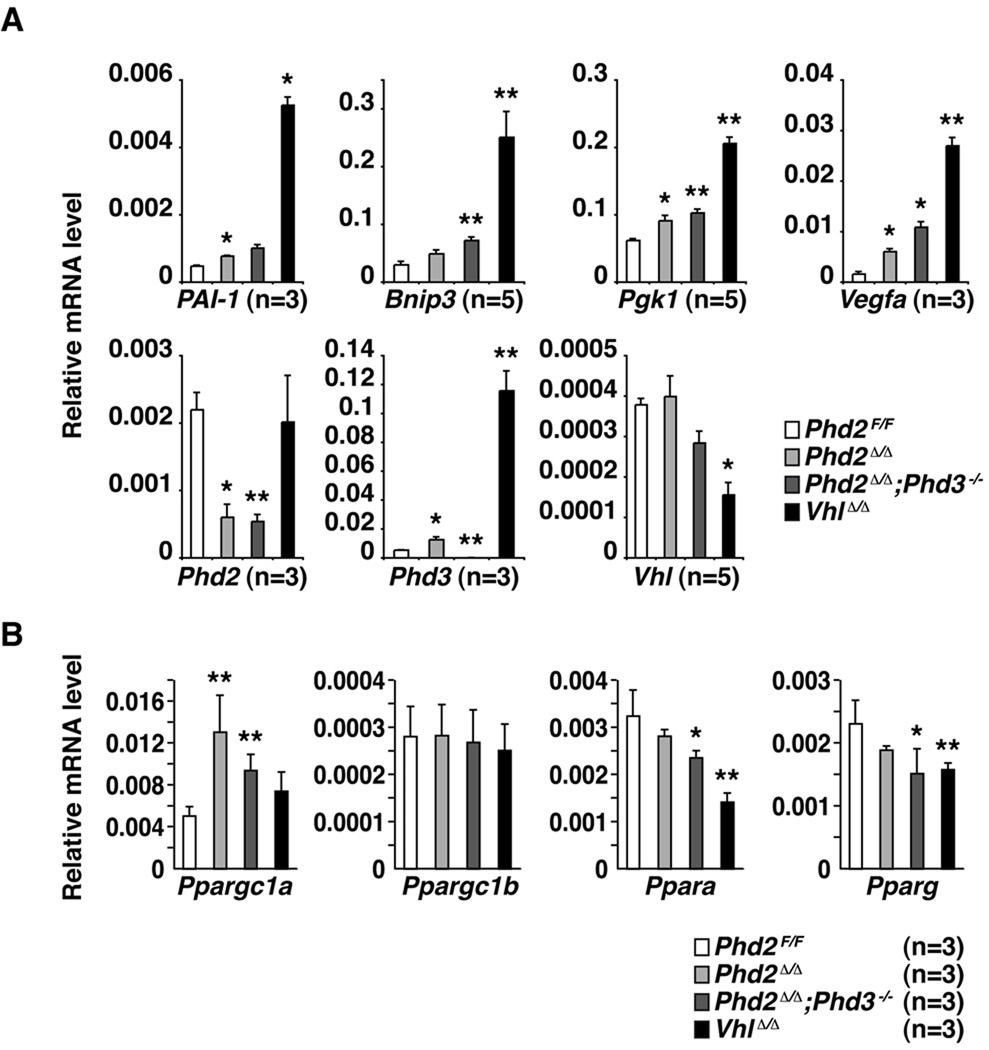

Figure 2. Accumulation of HIF-responsive mRNAs in PHD-Defective Hearts.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of hearts from 5 week old mice with the indicated genotypes. Values were normalized to β-Actin. *p<0.05 vs. Phd2F/F, **p<0.01 vs. Phd2F/F. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. Ppargc1a = peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α). Ppagrc1b = peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 beta (PGC-1β). Ppara = peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α). Pparg = peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPAR-β).

PHD3 is induced in cells and tissues lacking PHD2 and can partially compensate for PHD2 loss in vitro and in vivo with respect to HIF regulation 12, 13. We therefore also generated, through appropriate matings, Phd2 flox/flox;Phd3−/−; αMHC-Cre mice and Vhl flox/flox; αMHC-Cre mice. The latter served as a control in the experiments below since cardiac-specific VHL inactivation leads to HIF accumulation and cardiomyopathy 20, 21. Cardiac-specific recombination of the Phd2 locus in Phd2 flox/flox;Phd3−/−; αMHC-Cre mice was comparable to that observed in Phd2 flox/flox;Phd3+/+; αMHC-Cre mice (data not shown). Moreover, the Phd2 locus and Vhl locus were recombined with comparable efficiencies in these models (Figure 1A).

PHD2 and PHD3 Cooperate to Regulate Cardiac HIF Levels

As expected, HIF1α and HIF2α protein levels were increased in the hearts of Phd2 flox/flox;Phd3−/−; αMHC-Cre mice and in the hearts of Vhl flox/flox; αMHC-Cre mice compared to control littermates, as determined by immunoblot and immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 1D and 1E). As seen by us before following systemic inactivation of VHL or PHD family members 13, HIF2α accumulated to higher levels in hearts lacking VHL compared to hearts lacking PHD2 and PHD3. This might reflect a contribution of PHD1 to the control of HIF2α hydroxylation in the heart or perhaps a hydroxylase-independent pVHL activity. Notably, HIF1α and HIF2α protein levels were barely increased in hearts lacking PHD2 alone and were not demonstrably increased in hearts lacking PHD3 alone. These findings support that PHD2 and PHD3 cooperate to regulate HIF activity in the heart and document that the levels of HIF achieved in the Phd2 flox/flox;Phd3+/+; αMHC-Cre model are significantly lower than achieved after cardiac-specific VHL inactivation.

The accumulation of HIF1α and HIF2α in hearts lacking both PHD2 and PHD3 led, as predicted, to the increased accumulation of a number of well-studied HIF-responsive mRNAs including mRNAs controlling metabolism, angiogenesis, and autophagy (Figure 2). Notably, a number of these same targets were also induced, albeit at lower levels, in hearts lacking PHD2 alone, despite the modest induction of HIF1α and HIF2α protein in this setting (Figure 2). This discrepancy presumably reflects the sensitivity of the real-time PCR assays for the HIF transcriptional signature compared to the sensitivity of the HIF immunoblot and immunohistochemical assays using the currently available antibodies. Although HIF has been reported to affect p53 29 we did not see stabilization of p53, or activation of canonical p53 targets, in PHD2-defective hearts (Supplemental Fig 1and data not shown).

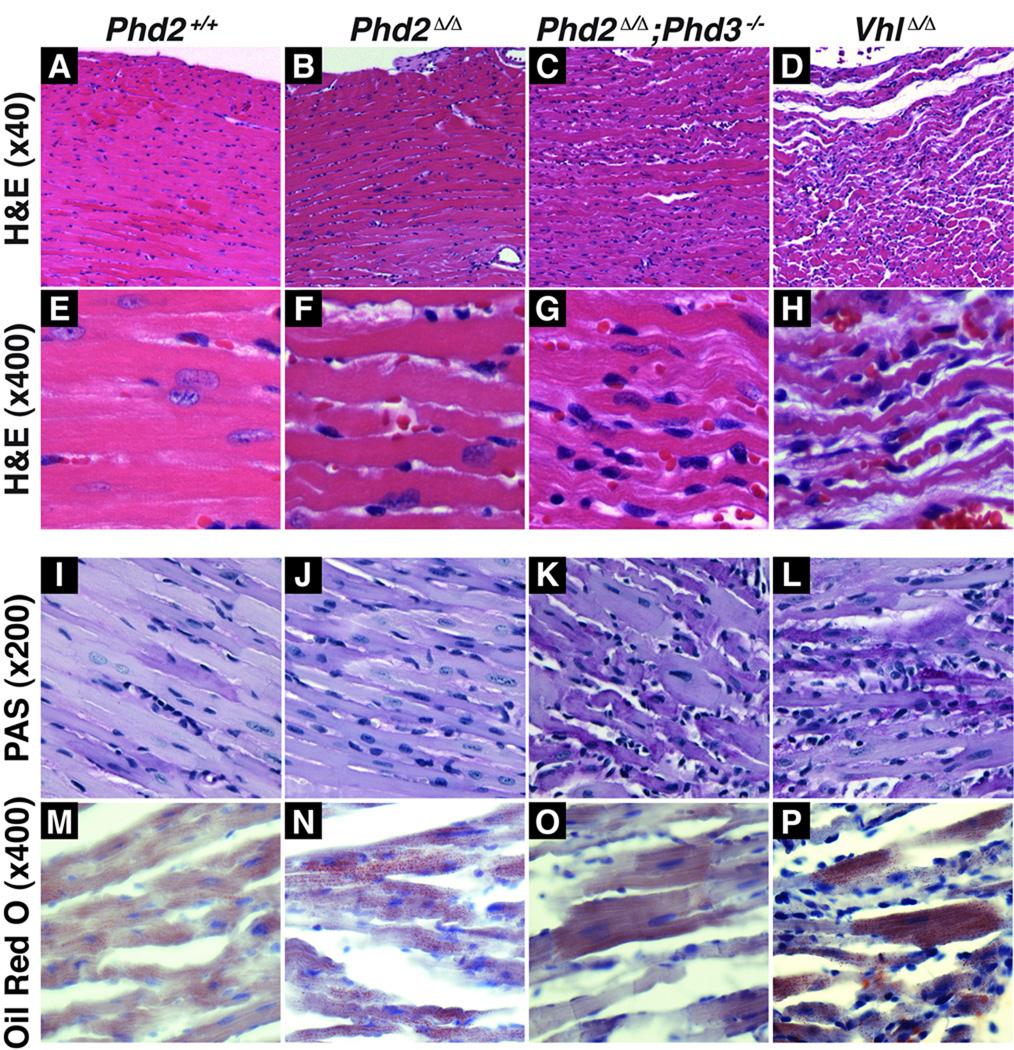

PHD Inactivation in Cardiomyocytes Causes Cardiomyopathy

To determine the consequences of chronic PHD inactivation on the heart, we performed histological studies on hearts obtained from 8 week old mice (Figure 3A–P). Hearts lacking both PHD2 and PHD3 exhibited notable degenerative changes of the cardiomyocytes with areas of myocyte dropout. These abnormalities were even more pronounced in hearts lacking pVHL, in which there was a profound loss of myocytes and increased interstitial spaces between myofibers consistent with significant cardiomyopathy. In contrast, the only abnormality detected in hearts lacking PHD2 alone was the presence of occasional myocytes with increased hypereosinophilia and blurring of the cross-striations, possibly representing early myocardial damage. No significant fibrosis was present by Masson’s trichrome staining in any of the models at 8 weeks (data not shown).

Figure 3. Histological Abnormalities in PHD-Defective Hearts.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining at low (A–D) and high power magnification (E–H), PAS staining (I–L), and Oil Red O staining (M–P) of hearts from 8 week old mice with the indicated genotypes.

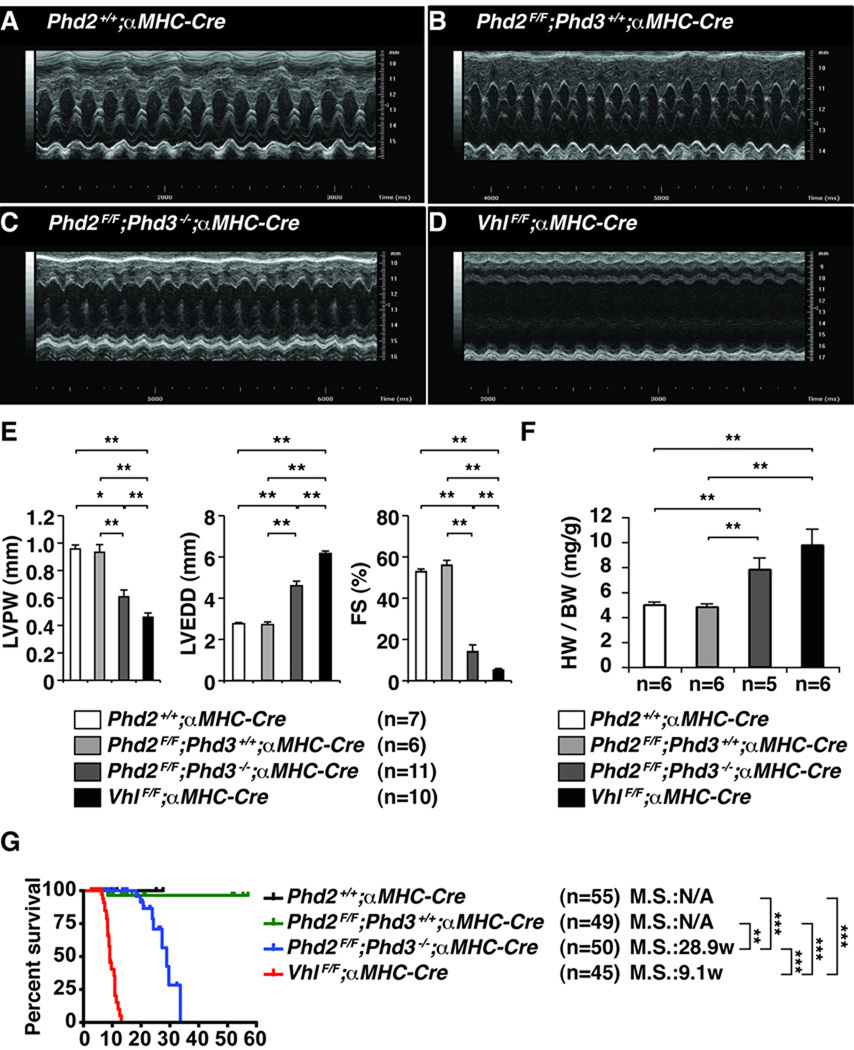

To ascertain the functional consequences of PHD inactivation we performed echocardiography in 5 week old and 8 week old mice (Figure 4A–D). Combined loss of PHD2 and PHD3 in the heart led to significant left ventricular dysfunction that was first apparent at approximately 5 weeks of age (data not shown) and was severe by 8 weeks of age (Figure 4E and Supplemental Movies 1 and 2). This loss of contractility was associated with myocardial thinning and left ventricular dilatation, all consistent with severe cardiomyopathy. Similar changes, but with reduced latency and increased severity, were noted after cardiac-specific VHL inactivation. It should be noted that the defects we observed in pVHL-defective hearts arose more rapidly than was described by Giordano and coworkers, probably because they used a different cardiac-specific Cre strain (MLC2v-Cre). In addition, combined PHD2 and PHD3 inactivation in the heart led to significant cardiomegaly, as evidenced by increased heart weight to body weight ratio, in 7–8 week old mice (Figure 4F). These changes were associated with premature mortality (median survival of ~30 weeks for mice whose hearts lacked PHD2 and PHD3 and ~10 weeks for mice whose hearts lacked VHL) (Figure 4G). In contrast to our earlier findings after systemic inactivation of PHD211, however, we did not detect overt cardiomyopathy after cardiac-specific inactivation of PHD2 alone.

Figure 4. Chronic PHD Inactivation in the Heart Leads to Cardiomyopathy and Premature Death.

A–D, Representative echocardiograms (M-mode view) of 5-week-old mice with the indicated genotypes. E, Echocardiographic parameters including left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPW), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and fractional shortening (FS) of mice with indicated genotypes at 8 weeks of age. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. F, Heart weight/body weight ratio (HW/BW) for 5 week old mice with the indicated genotypes. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. G, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mice with the indicated genotypes. **P<0.01. ***P<0.001.

Decompensation of Hearts Lacking PHD2 Subjected to Increased Afterload

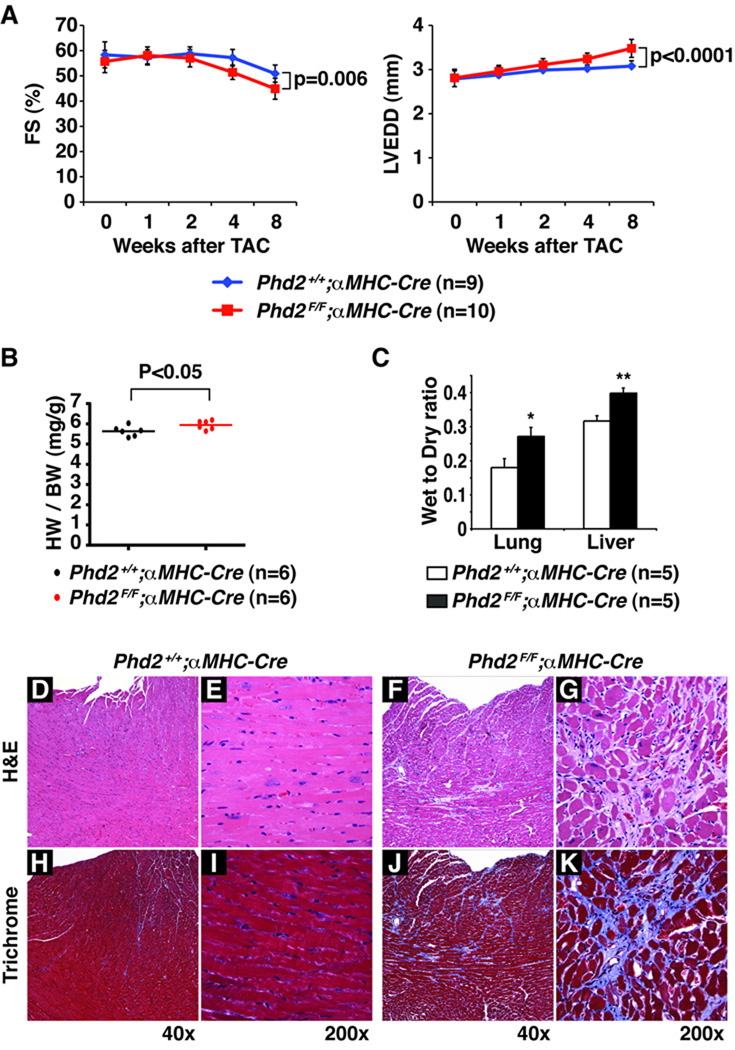

We hypothesized that the cardiomyopathy seen in the setting of systemic PHD2 inactivation was due to a combination of cell-intrinsic effects of PHD2 loss in the heart and the increased stress created by the concurrent polycythemia, which would be predicted to increase blood volume (preload) and viscosity (leading to an apparent increase in outflow resistance or afterload). Tranverse aortic constiction (TAC) is a well-established model wherein clamping of the aorta is used to increase afterload. We chose a TAC model in which the clamp is placed distal to the right inominate artery, which leads to a mild increase in afterload, as opposed to the proximal ascending aorta, which creates a severe impediment to outflow. In this way we hoped to mimic the hemodynamic stress that might occur in the setting of chronic polycythemia. Female Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice and age and sex-matched Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre control mice were subjected to TAC and non-invasively monitored for the next 8 weeks by serial echocardiography (Figure 5). During the first four weeks, both Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice and control Phd2 +/+;α MHC-Cre mice compensated for the increased hemodynamic load by undergoing cardiac hypertrophy (data not shown). Thereafter hearts lacking Phd2 exhibited more profound decompensation relative to Phd2-intact hearts, as determined by decreased fractional shortening (FS)(Figure 5A) and increased left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD)(Figure 5B). This effect was a result of the TAC, as sham operated mice did not show similar echocardiographic changes after 8 weeks (Data not shown). We saw even earlier and more profound decompensation after TAC in male Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre compared to Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre control mice (Supplemental Figure 2). The enhanced sensitivity of male mice to TAC relative to females has been reported before and presumably reflects, at least in part, a cardioprotective effective of estrogen, consistent with previous published reports30.

Figure 5. Decompensation of Female PHD2-defective Hearts in Response to Increased Afterload.

A, Fractional shortening (FS) (%) and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) after transverse aortic constriction in 8–10 week old mice with the indicated genotypes. Error bars indicate 1 SD. B, Heart weight/body weight ratio (HW/BW)) 8 weeks after TAC in mice with the indicated genotypes. C, Wet weight to dry weight ratios for lungs and livers from mice with the indicated genotypes 8 weeks after TAC. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. D–K, Hematoxylin and eosin staining (D–G) and Trichrome staining (H–K) of hearts from mice with the indicated genotypes 8 weeks after TAC.

The mice were all sacrificed 8 weeks after TAC. Hearts from Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice were grossly enlarged (data not shown) and increased in weight (normalized to body weight) compared to control mice (Figure 5B). Histological evaluation of the PHD2-defective hearts showed myocyte dropout with replacement and interstitial fibrosis compared to PHD2-intact hearts (Figure 5D–K). In addition, TAC resulted in increased congestion as evidenced by increased lung and liver weights in Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice compared to Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre control mice (Figure 5C). Taken together, these data imply that the deleterious consequences of cardiac-specific PHD2 inactivation can be unmasked by certain forms of stress.

Aging can exacerbate certain forms of cardiomyopathy, including ischemic cardiomyopathy, and unmask subclinical myocardial abnormalities. As a result, cardiomyopathy is largely seen in older individuals. We therefore performed serial echocardiograms and timed-necropsies on Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice and sex-matched, littermate control Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre mice. The echocardiograms of 12 week old Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice were indistinguishable from those of the control mice (data not shown). At necropsy, however, the myocytes from the Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice were larger, indicative of hypertrophy (Supplementary Figure 2B). Moreover, by 36 weeks of age the echocardiograms of Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre exhibited signs of mild left ventricular dysfunction, with increased LVPW and decreased fractional shortening (Supplementary Figure 3A). Therefore the deleterious consequences of PHD2 inactivation in the heart are accentuated by aging and stress.

Deregulated Angiogenesis, Metabolism, and Mitochondria in PHD-defective Hearts

To begin to understand the mechanism(s) by which PHD loss might promote the development of cardiomyopathy, we considered the well documented roles of HIF in the control of angiogenesis, metabolism, and mitochondrial turnover. For example, PHD loss, and HIF activation, leads to the upregulation of angiogenic factors including the canonical HIF target VEGF (see also Figure 2A). As expected, capillary density was increased in the hearts lacking PHD2, especially when combined with PHD3 loss, as determined by anti-CD34 and anti-CD31/PECAM staining (Supplemental Fig 4). It is possible that this increased capillary network contributes to cardiac dysfunction through changes in tissue architecture, interstitial edema, or perhaps paracrine signaling between endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes.

HIF promotes glucose and fatty acid uptake, aerobic glycolysis and glucose to lipid conversion while inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid beta oxidation. For example, HIF appears to be both necessary and sufficient for the development of hepatosteatosis arising from VHL inactivation in that organ 24, 26, 31 and is necessary for the accumulation of glycogen and lipids detected in hearts lacking pVHL 21. Consistent with a profound reprogramming in cellular metabolism, hearts lacking PHD function accumulated both glycogen and lipid, as determined by PAS and oil Red O staining, respectively (Figure 3I–P).

The metabolic regulatory transcription factor PPARγ is HIF-responsive in some contexts 21. Surprisingly, however, we have not, so far, detected an increase in PPARγ in either pVHL-defective or PHD-defective hearts taken from young mice prior to the onset of cardiomyopathy (Figure 2B). Moreover, we did not detect an increase in PPARα in pVHL-defective or PHD-defective hearts, despite the reported induction of this transcription factor in PHD1-defective skeletal muscle 15. These observations suggest that induction of neither PPARα nor PPARγ is necessary for the metabolic derangements observed in PHD-defective hearts (Figure 2B).

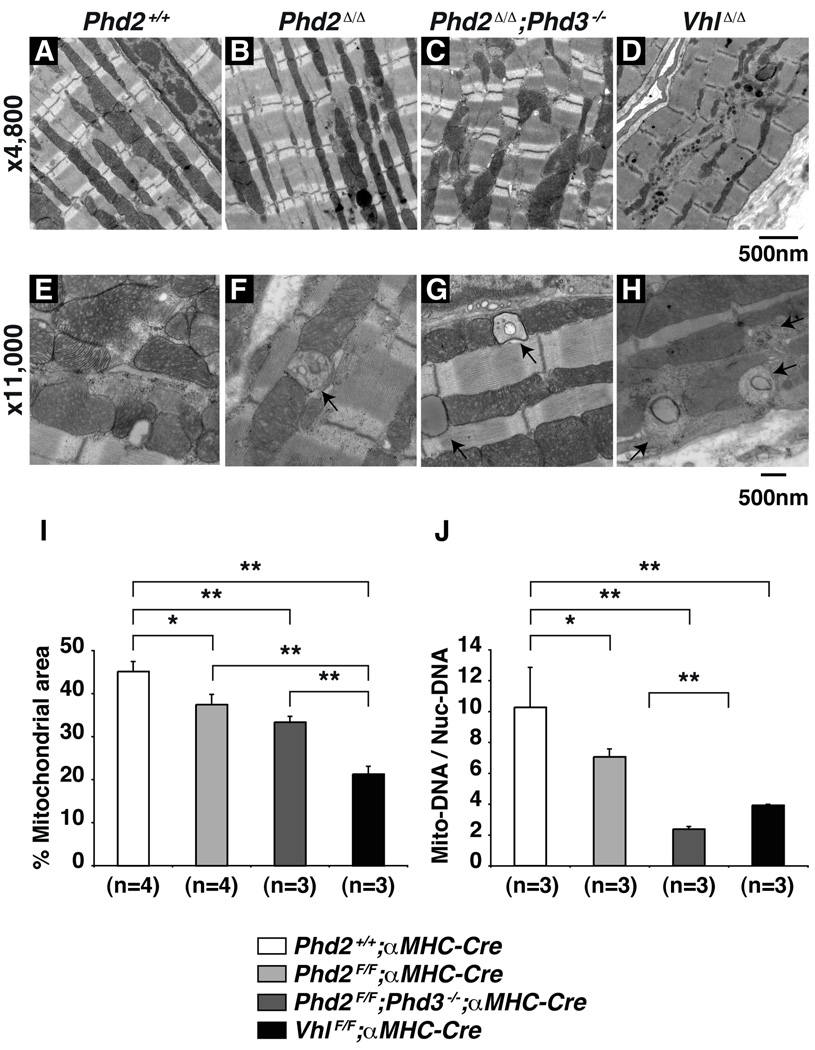

Finally, we conducted electron microscopy studies because HIF has been reported to inhibit mitochondrial biogenesis by downregulating PGC-1β and to promote mitophagy by upregulating BNIP3 32–34 (Figure 6A–H). Indeed, ultrastructural analysis of hearts lacking PHD2 and PHD3, or lacking VHL, revealed relatively intact sarcomeric structures but grossly abnormal mitochondria, including mitochondrial remnants that were suggestive of mitophagy (Figure 6E–H). Mitochondrial abnormalities, including mitochondrial swelling and early signs of degeneration, were also detected Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre hearts that had scored normally by echocardiography immediately prior to harvest. Quantification showed that mitochondrial area was progressively diminished by PHD2 loss, combined PHD2 and PHD3 loss, or pVHL loss (Figure 6I). Oxygen consumption was diminished in PHD2-defective mouse embryo fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes, consistent with impaired mitochondrial function (Supplemental Fig 5).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial Loss in PHD-defective Hearts.

A–D, Representative electron microscopy from 5 week old mice hearts with indicated genotypes. Note relatively normal sarcomeric structure but abnormal mitochondria in hearts lacking PHD2 (especially when combined with PHD3 loss) or pVHL. E–H, Evidence of mitochondrial autophagy in 5 week old hearts with indicated genotypes. I, Percent mitochondrial area of total myocytes area for mice with indicated genotypes. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. J, Copy number of Mitochondrial (mt-Co1) DNA, normalized to nuclear DNA (Rn18s), as determined by real-time PCR, from hearts as in A–D. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean.

In a complementary set of experiments, we measured the amount of mitochondrial DNA by real-time PCR. The copy number of the mitochondrial gene mt-Co1, normalized to nuclear genome DNA (Rn18s), was significantly decreased in Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice compared to control Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre mice (Figure 6J). This decrease was even more pronounced, however, in the hearts lacking both PHD2 and PHD3 and in hearts lacking VHL, consistent with the ultrastructural images. Of note, BNIP3 was induced in hearts lacking either PHD function or pVHL function, and mirrored the degree of cardiac decompensation, whereas we have not, thus far, detected a decrease in PGC-1α or PGC1β in our models (Figure 2). This, together with the electron microscopy data, suggests that mitophagy contributes to the development of cardiomyopathy in hearts lacking PHD or pVHL function.

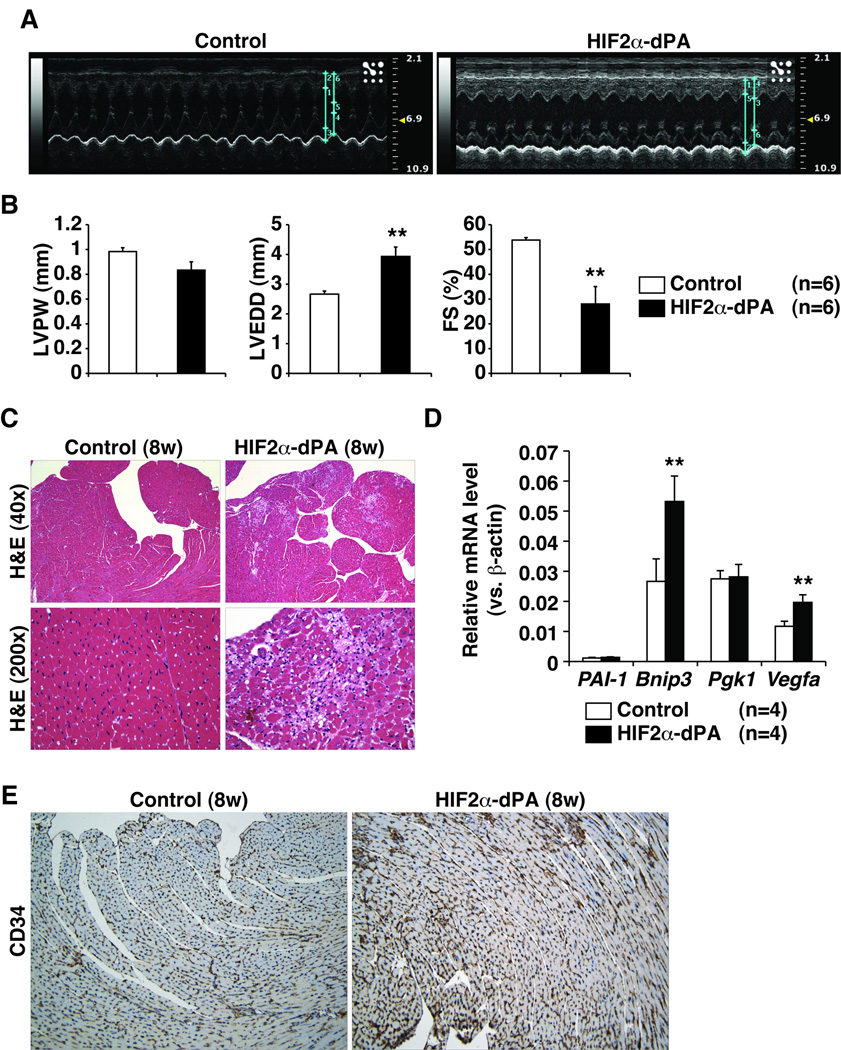

Chronic HIF activation is Sufficient to Cause Cardiomyopathy

pVHL has HIF-independent functions and the same is likely true for the PHD family members 22, 23. To ask if HIF activation is sufficient to induce cardiomyopathy, we crossed αMHC-Cre with mice we created earlier that carry a conditional HIF2α allele that contains a LoxP-Stop-LoxP cassette upstream of a cDNA encoding a non-hydroxylatable HIF2α variant (HIF2α dPA) 26. This variant HIF2α allele was inserted into the ROSA26 locus by homologous recombination. Echocardiograms of eight week old ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+; αMHC-Cre mice showed signs of dilated cardiomyopathy including left ventricular dilatation and decreased fractional shortening (Figure 7A–7B) although there was no statistical difference in left ventricular wall thickness and no evidence of cardiomegaly at this timepoint (Figure 7B and data not shown). Histological evaluation of hearts from eight week old ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+; αMHC-Cre mice showed predominantly subendocardial myocardial injury with myocyte dropout and evidence of healing (Figure 8C). By 11 weeks of age ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+; αMHC-Cre mice exhibited more pronounced echocardiographic and histological signs of congestive heart failure, which was associated with more pronounced myocyte dropout and fibrosis (Supplemental Figure 6). In addition, evaluation of lung and liver of the showed evidence of congestion consistent with early clinical heart failure (data not shown). Finally, ROSA26 HIF2α dPA/+; αMHC-Cre hearts accumulated a subset of HIF-target genes (Figure 7D) and exhibited increased angiogenesis (Figure 7E). Therefore chronic HIF activation is sufficient to cause cardiomyopathy.

Figure 7. HIF Activation is Sufficient to Induce Cardiomyopathy.

A, Representative echocardiograms (M-mode view) of 8-week-old mice with the indicated genotypes. B, Echocardiographic parameters including left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPW), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and fractional shortening (FS) of mice with indicated genotypes at 8 weeks of age. **P<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. C, Hematoxylin and eosin staining at low magnification (40×) and high power magnification (200×) of 8 week old mice with indicated genotypes. D, Real-time RT-PCR analysis in 8-week-old control (Rosa26+/+; αMHC-Cre) or HIF2α-dPA (Rosa26HIF2α dPA/+;αMHC-Cre) hearts. **p<0.01. Error bars indicate 1 standard error of mean. Note that Pgk1 is a HIF1α, but not a HIF2α, transcriptional target. E, Representative anti-CD34 staining of hearts from 8 week old mice with indicated genotypes.

Figure 8. Role of HIF in Chronic Ischemic Cardiomyopathy.

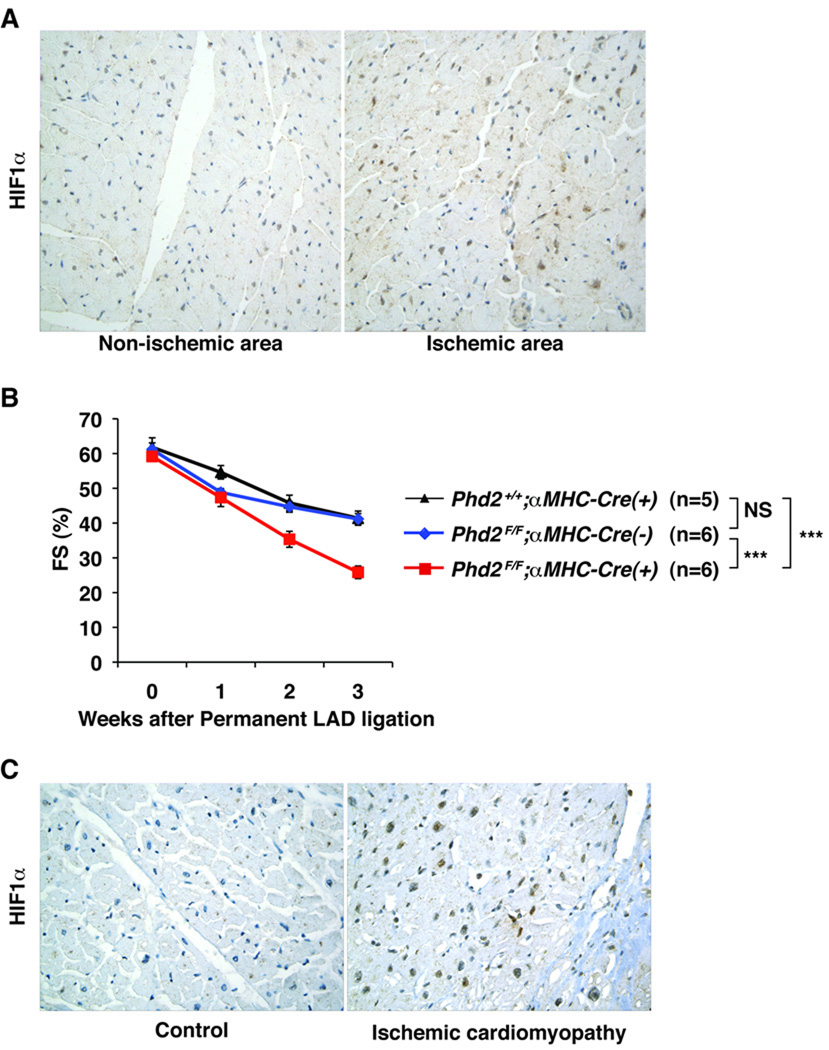

A, Representative immunohistochemistry analysis of HIF1α in non-ischemic and ischemic areas of the wild-type hearts 3 weeks after LAD ligation. B, Fractional Shortening in Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice and PHD2-proficient control mice (Phd2 flox/flox mice and Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre mice) after LAD ligation. ***p<0.0001. NS = not significant. C, Representative immunohistochemistry analysis of HIF1α in hearts obtained at autopsy from patients with or without (control) ischemic cardiomyopathy.

To further explore the potential role of HIF in chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, we subjected wild-type mice to permanent LAD occlusions (Fig 8). As expected, HIF protein levels were increased, as determined by immunohistochemistry, in the ischemic myocardium 1 week (data not shown) and 3 weeks (Fig 8A) later. Next Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice, which lack cardiac PHD2, as well as PHD2-proficient control mice (Phd2 flox/flox mice and Phd2 +/+;αMHC-Cre mice) were subjected to permanent LAD ligations. Interestingly, infarct sizes and perioperative (periinfarct) mortality was significantly lower in the Phd2 flox/flox; αMHC-Cre mice compared to the PHD2-proficient mice, consistent with PHD2 loss having a protective effect during an acute MI (J.M. and W.G.K.-manuscript in preparation). However cardiac function deteriorated more rapidly in Phd2 flox/flox; αMHC-Cre mice compared to PHD2 proficient animals, consistent with a deleterious role for sustained HIF activation (Figure 8B). HIF activation is a predictable consequence of impaired oxygen delivery and has been documented in the setting of acute ischemia in humans 7. Moreover, we documented increase HIF levels in the limited number of autopsy samples available to us from patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy (n = 3) (Figure 8C). Collectively, these results suggest that chronic HIF activation contributes to the pathogenesis of chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

We found that chronic inactivation of PHD2 in cardiomyocytes, especially when combined with PHD3 loss, leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and premature mortality. PHD3 compensates for PHD2 loss in many settings and, perhaps as a result, hearts lacking PHD2 alone displayed only subtle abnormalities under non-stress conditions. Nonetheless, hearts lacking PHD2 are clearly compromised when subjected to stress, such as imposed by transverse aortic constriction, permanent LAD occlusion, or, as shown by us previously, by polycythemia 11.

Our findings have potential implications with respect to the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. The loss of myocardial contractility that occurs in the setting of chronic coronary artery disease could, in theory, simply reflect the consequences of repeated myocardial infarctions, leading to loss of viable heart muscle and ventricular remodeling, together with diminished delivery of fuel in the form of oxygen and nutrients. Our studies, however, suggest that loss of PHD activity, which is a predictable consequence of chronic ischemia, is sufficient to induce many of the histological, ultrastructural, and functional hallmarks of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Thus, loss of PHD activity, per se, may be a driving force in the development of ischemic cardiomyopathy. If true, this would explain why the degree of systolic dysfunction in some patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy is out of proportion to the amount of infarcted tissue in their hearts and would suggest that the benefits of successful coronary revascularization are due, at least partly, to restoration of PHD activity as a consequence of improved tissue oxygenation.

This idea is consistent with a study of Keshet and coworkers, who used a tunable transgene encoding a VEGF trap to reversibly induce myocardial ischemia in mice in the absence of overt infarction 35. They reported that ischemia caused HIF activation (indicative of impaired PHD function), metabolic reprogramming, mitochondrial autophagy, and systolic dysfunction that were completely reversed upon removal of the VEGF trap. It should be noted that their study used bona fide ischemia (due to loss of blood vessels) to inactivate PHD function and hence the phenotypes they observed could have reflected PHD-independent effects of oxygen deprivation. In contrast, we inactivated PHD genetically without inhibiting angiogenesis or oxygen delivery.

We have not yet formally proven that HIF activation is necessary for the development of cardiomyopathy in the setting of PHD inactivation. On the other hand, previous studies showed that HIF activation is necessary for the development of cardiomyopathy in the setting of pVHL loss and in a model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 20, 21. The former is especially notable because the cardiac phenotype after pVHL loss is more severe than observed after inactivation of PHD2 and PHD3, presumably because of the residual activity of PHD1 and perhaps other, HIF-independent pVHL functions. The finding that eliminating HIF1α ameliorates the cardiac abnormalities in pVHL-defective strongly suggests that the same would be true in PHD-defective hearts. Moreover, we found that expression of a stabilized version of HIF2α in the heart is sufficient to induce cardiomyopathy. Ralph Shohet has obtained similar results using a stabilized version of HIF1α (personal communication). Collectively, these results support that HIF plays a causal role in the development of cardiomyopathy in the setting of PHD inactivation.

The induction of cardiomyopathy by HIF is likely to be multifactorial. For example, a number of well-studied HIF target genes play key roles in metabolism and mitochondrial turnover. Moreover, a recent study emphasized the importance of HIF1α and the HIF-responsive transcription factor PPARγ in the control of cardiac glucose and lipid homeostasis 21. HIF activation was shown to play a necessary role in the development of metabolic reprogramming and contractile dysfunction in models of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

We also documented a robust increase in angiogenesis in PHD-defective hearts. The induction of angiogenesis in ischemic myocardium is usually assumed to be a step toward restoring the delivery of blood to the heart and hence to be adaptive. It is possible, however, that unbridled angiogenesis eventually contributes to cardiac dysfunction in the setting of chronic ischemia. Further studies are clearly required to determine whether the increase in angiogenesis observed in PHD-defective hearts is adaptive, maladaptive, or simply a biomarker for sustained HIF activation.

Chronic HIF activation also leads to a loss of mitochondria through decreases in mitochondrial biogenesis and increased mitochondrial autophagy 32–34. Mitochondrial autophagy clearly plays a key role in cardiac homeostasis. Whether mitophagy is an adaptive or deleterious response to chronic myocardial ischemia, however, remains controversial 36–38. It will be of interest to determine whether inhibiting autophagy alters the natural history of PHD-defective mice.

Our findings in no way preclude a beneficial role of HIF in the setting of acute myocardial ischemia. Indeed, HIF activates many genes that would be predicted to sustain energy levels and survival in a low-oxygen environment. Moreover, inhibition of PHD function with small organic molecules or with interfering RNAs4, 14, 16, 39, as well as transgenic express of HIF1α in the heart 6, has been reported to be beneficial in preclinical models of acute myocardial infarction. Conversely, HIF1 loss leads to decreased cardioprotection from ischemic preconditioning 40, 41. Consistent with these findings, we found that infarct size and perinfarct mortality were reduced in Phd2 flox/flox;αMHC-Cre mice compared to littermate controls in ischemia-reperfusion models and LAD permanent occlusion models (J.M. and W.G.K.-unpublished data). Similar findings have been observed in mice carrying a hypomorphic Phd2 allele 42. Collectively, these results suggest that HIF activation is beneficial in the setting of acute myocardial ischemia even if protracted HIF activation is deleterious. Precedence for such an idea comes from studies of Phd1−/− mice. The limb muscles of such mice are protected from acute ischemia, in a HIF-dependent manner, but have diminished performance during exercise 15. These two phenomena appear to be linked to a shift to glycolysis and diminished oxidative stress during hypoxia (due to decreased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation) 15.

A number of small molecule PHD inhibitors are in various stages of development for the treatment of anemia and ischemia. Our findings suggest that the chronic use of such agents might cause cardiomyopathy. However, it remains possible that the threshold of HIF activity required for therapeutic effects (for example, induction of red blood cell production) is lower than the threshold required for deleterious effects. In this regard, several observations are perhaps noteworthy. First, PHD inhibitor use in the clinic will almost certainly lead to submaximal, non-continuous, PHD inhibition, in contrast to the genetic models described here. Second, the dose-response curves relating PHD activity to HIF-target gene induction are not stereotypical. Instead, they differ for different HIF target genes and in different tissues. For example, near maximal induction of erythropoietin in the kidney is achieved after PHD2 inactivation, whereas the maximal induction of some other HIF target genes requires the concurrent inactivation of other PHD paralogs and/or the HIF asparaginyl hydroxylase FIH1, which regulates HIF transactivation function 13. Finally, cardiomyopathy is not a conspicuous feature of patients with hypomorphic PHD2 mutations 43, 44 or with chronic hypoxemia and polycythemia from non-cardiac causes.

In summary, our genetically-defined mouse models establish the plausibility that chronic PHD inactivation, and consequent HIF activation, plays a cause role in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. These models should be useful for dissecting the contributions of specific HIF target genes to the development of cardiomyopathy and for testing whether pharmacological manipulation of HIF, or its downstream targets, can alter the natural history of this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Collins and Soeun Ngoy for technical support. This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Kenneth Baughman.

Sources of Funding

JM was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grants for cardiovascular research (T32HL007604-24 and K08HL097031), a Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) Research Fellowship, and the Watkins Cardiovascular Discovery Award (from Brigham and Women’s Hospital). WGK was supported by NIH, is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator, and is a Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

WGK consults for, and owns equity in, Fibrogen, Inc., which is developing prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for various indications.

Subject codes: [7] Chronic ischemic heart disease; [110] Congestive; [16] Myocardial cardiomyopathy disease; [130] Animal models of human disease; [107] Biochemistry and metabolism

References

- 1.McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA. Heart failure. Lancet. 2005;365:1877–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gheorghiade M, Bonow RO. Chronic heart failure in the United States: a manifestation of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1998;97:282–289. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaelin WG, Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckle T, Kohler D, Lehmann R, El Kasmi K, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 is central to cardioprotection: a new paradigm for ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 2008;118:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurgensen JS, Rosenberger C, Wiesener MS, Warnecke C, Horstrup JH, Grafe M, Philipp S, Griethe W, Maxwell PH, Frei U, Bachmann S, Willenbrock R, Eckardt KU. Persistent induction of HIF-1alpha and -2alpha in cardiomyocytes and stromal cells of ischemic myocardium. Faseb J. 2004;18:1415–1417. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1605fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kido M, Du L, Sullivan CC, Li X, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha reduces infarction and attenuates progression of cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction in the mouse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2116–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SH, Wolf PL, Escudero R, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Early expression of angiogenesis factors in acute myocardial ischemia and infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:626–633. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein A, Gleadle J, McNeill L, Hewitson K, O'Rourke J, Mole D, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson M, Dhanda A, Tian Y, Masson N, Hamilton D, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell P, Pugh C, Schofield C, Ratcliffe P. C. elegans EGL-9 and Mammalian Homologs Define a Family of Dioxygenases that Regulate HIF by Prolyl Hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruick R, McKnight S. A Conserved Family of Prolyl-4-Hydroxylases That Modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouves A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouyssegur J. HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. Embo J. 2003;22:4082–4090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG., Jr Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood. 2008;111:3236–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appelhoff RJ, Tian YM, Raval RR, Turley H, Harris AL, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Gleadle JM. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Padera RF, Bronson RT, Liao R, Kaelin WG., Jr A feedback loop involving the Phd3 prolyl hydroxylase tunes the mammalian hypoxic response in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5729–5741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00331-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang M, Chan DA, Jia F, Xie X, Li Z, Hoyt G, Robbins RC, Chen X, Giaccia AJ, Wu JC. Short hairpin RNA interference therapy for ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2008;118:S226–S233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aragones J, Schneider M, Van Geyte K, Fraisl P, Dresselaers T, Mazzone M, Dirkx R, Zacchigna S, Lemieux H, Jeoung NH, Lambrechts D, Bishop T, Lafuste P, Diez-Juan A, Harten SK, Van Noten P, De Bock K, Willam C, Tjwa M, Grosfeld A, Navet R, Moons L, Vandendriessche T, Deroose C, Wijeyekoon B, Nuyts J, Jordan B, Silasi-Mansat R, Lupu F, Dewerchin M, Pugh C, Salmon P, Mortelmans L, Gallez B, Gorus F, Buyse J, Sluse F, Harris RA, Gnaiger E, Hespel P, Van Hecke P, Schuit F, Van Veldhoven P, Ratcliffe P, Baes M, Maxwell P, Carmeliet P. Deficiency or inhibition of oxygen sensor Phd1 induces hypoxia tolerance by reprogramming basal metabolism. Nat Genet. 2008;40:170–180. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philipp S, Jurgensen JS, Fielitz J, Bernhardt WM, Weidemann A, Schiche A, Pilz B, Dietz R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Eckardt KU, Willenbrock R. Stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor rather than modulation of collagen metabolism improves cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction in rats. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ockaili R, Natarajan R, Salloum F, Fisher BJ, Jones D, Fowler AA, 3rd, Kukreja RC. HIF-1 activation attenuates postischemic myocardial injury: role for heme oxygenase-1 in modulating microvascular chemokine generation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H542–H548. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00089.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernhardt WM, Campean V, Kany S, Jurgensen JS, Weidemann A, Warnecke C, Arend M, Klaus S, Gunzler V, Amann K, Willam C, Wiesener MS, Eckardt KU. Preconditional activation of hypoxia-inducible factors ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1970–1978. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiq A, Ayoub IA, Chavez JC, Aminova L, Shah S, LaManna JC, Patton SM, Connor JR, Cherny RA, Volitakis I, Bush AI, Langsetmo I, Seeley T, Gunzler V, Ratan RR. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition. A target for neuroprotection in the central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41732–41743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504963200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei L, Mason S, Liu D, Huang Y, Marks C, Hickey R, Jovin IS, Pypaert M, Johnson RS, Giordano FJ. Hypoxia inducible factor-dependent degeneration, failure, and malignant transformation of the heart in the absence of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01580-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnan J, Suter M, Windak R, Krebs T, Felley A, Montessuit C, Tokarska-Schlattner M, Aasum E, Bogdanova A, Perriard E, Perriard JC, Larsen T, Pedrazzini T, Krek W. Activation of a HIF1alpha-PPARgamma axis underlies the integration of glycolytic and lipid anabolic pathways in pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2009;9:512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaelin WG. von Hippel-Lindau Disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2007;2:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.092049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frew IJ, Krek W. pVHL: a multipurpose adaptor protein. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe30. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.124pe30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haase V, Glickman J, Socolovsky M, Jaenisch R. Vascular tumors in livers with targeted inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1583–1588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim WY, Safran M, Buckley MR, Ebert BL, Glickman J, Bosenberg M, Regan M, Kaelin WG., Jr Failure to prolyl hydroxylate hypoxia-inducible factor alpha phenocopies VHL inactivation in vivo. Embo J. 2006;25:4650–4662. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao R, Jain M, Cui L, D'Agostino J, Aiello F, Luptak I, Ngoy S, Mortensen RM, Tian R. Cardiac-specific overexpression of GLUT1 prevents the development of heart failure attributable to pressure overload in mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2125–2131. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034049.61181.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao R, Jain M. Isolation, culture, and functional analysis of adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Methods Mol Med. 2007;139:251–262. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-571-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmid T, Zhou J, Brune B. HIF-1 and p53: communication of transcription factors under hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:423–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura T, Said S, Gerdes AM. Gender-related differences in myocyte remodeling in progression to heart failure. Hypertension. 1999;33:676–680. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.2.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rankin EB, Rha J, Selak MA, Unger TL, Keith B, Liu Q, Haase VH. HIF-2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, Gonzalez FJ, Semenza GL. Mitochondrial autophagy is a HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Zhang H, Gao P, Fukuda R, Kumar G, Krishnamachary B, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Semenza GL. HIF-1 inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular respiration in VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma by repression of C-MYC activity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM. Hypoxia-induced autophagy is mediated through hypoxia-inducible factor induction of BNIP3 and BNIP3L via their BH3 domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2570–2581. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00166-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.May D, Gilon D, Djonov V, Itin A, Lazarus A, Gordon O, Rosenberger C, Keshet E. Transgenic system for conditional induction and rescue of chronic myocardial hibernation provides insights into genomic programs of hibernation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:282–287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707778105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan L, Vatner DE, Kim SJ, Ge H, Masurekar M, Massover WH, Yang G, Matsui Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. Autophagy in chronically ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitsis RN, Peng CF, Cuervo AM. Eat your heart out. Nat Med. 2007;13:539–541. doi: 10.1038/nm0507-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goswami SK, Das DK. Autophagy in the myocardium: Dying for survival? Exp Clin Cardol. 2006;11:183–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nwogu JI, Geenen D, Bean M, Brenner MB, Huang X, Buttrick PM. Inhibition of Collagen Synthesis with Prolyl 4-Hydroxylase Inhibitor Improves Left Ventricular Function and Alters the Pattern of Left Ventricular Dilation After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:2216–2221. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.097193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai Z, Manalo DJ, Wei G, Rodriguez ER, Fox-Talbot K, Lu H, Zweier JL, Semenza GL. Hearts from rodents exposed to intermittent hypoxia or erythropoietin are protected against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2003;108:79–85. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078635.89229.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai Z, Zhong H, Bosch-Marce M, Fox-Talbot K, Wang L, Wei C, Trush MA, Semenza GL. Complete loss of ischaemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice with partial deficiency of HIF-1{alpha} Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:463–470. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hyvarinen J, Hassinen IE, Sormunen R, Maki JM, Kivirikko KI, Koivunen P, Myllyharju J. Hearts of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylase-2 hypomorphic mice show protection against acute ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13646–13657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Percy MJ, Zhao Q, Flores A, Harrison C, Lappin TR, Maxwell PH, McMullin MF, Lee FS. A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:654–659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Beer PA, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. A novel erythrocytosis-associated PHD2 mutation suggests the location of a HIF binding groove. Blood. 2007;110:2193–2196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.