Abstract

Purpose:

Early onset of sexual activity has been linked to later substance abuse. Our study aimed to further describe the associations between Latina mothers’ and daughters’ early sexual activity and adult substance abuse.

Methods:

A survey was conducted with 92 Latina mother–daughter dyads whose members never experienced sexual abuse. Childhood sexual experience was defined as the occurrence of a consensual sexual encounter at the age of 15 years or younger. Substance abusers were identified by the extent of substance use during the 12 months prior to the interview. Path analysis was used to fit our conceptual models to the data.

Main findings:

Daughters’ current, adult substance abuse was associated independently with: their own childhood sexual experience (odds ratio [OR] = 6.0) and mothers’ current, adult substance abuse (OR = 2.0). Compared with daughters who first experienced sex after the age of 19, the odds of using substances were 17.7 times higher among daughters who had childhood sexual experience and 3.8 times higher among daughters who first experienced sex between the age of 16–19 years. Explicitly, sexual experiences between the ages of 16–19 years were also risk factors for later adult substance abuse. Mothers’ childhood sexual experience (OR = 7.3) was a strong predictor for daughters’ childhood sexual experience.

Conclusions:

Our study supported a link between mother and daughter childhood sexual experience among Latinas, and indicated it is a correlate of adult substance abuse. Family based substance abuse prevention efforts and future longitudinal studies should consider maternal childhood sexual experience as a potential indication of risk for Latina daughters.

Keywords: early sex, child sex, Latina, substance abuse

Introduction

The early onset of sexual activity has been linked to risky health behaviors such as having a greater number of sexual partners over time and substance abuse.1–3 Sexual activity for any teenage girl is risky due to multiple factors such as elevated risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI) and unwanted pregnancy. Girls who experience sex at the age of 15 years or younger are a particularly high risk subset for other physical and psychosocial health problems.4 These younger girls have been found to be more likely than boys to have sex with an older individual and more likely to be a victim of instances of involuntary or unwanted sex.4,5 Because children may not fully understand the potential consequences of sex, having sexual contact with a girl who has not reached the legal age of consent is considered statutory rape. In most states, it is illegal to have sex with a girl aged 15 years or younger.

Individual abilities, traits, norms, and behaviors have been found to be transferred from parents to their children. Behavioral scientists have particularly focused on the intergenerational transmission of problem behaviors.6 Parents’ personality and behavioral attributes are thought to be transmitted across generations through parenting and the parent–child relationship. 6 Parent socioeconomic adversity,7 welfare dependency,8 antisocial and problem behaviors9–11 have been observed in the behaviors of their children. Children who were exposed to inter parental violence were also at an elevated risk for using violent conflict resolution within intimate relationships.12 In light of this literature, mother and child health risky behaviors within the understudied Latino mother–daughter dyad, are particularly important to investigate.

While studies support that the early onset of sexual activity is a negative life event,13,14 the intergenerational connection of early sex is not well understood, particularly among Latinas in the United States (US). Studies have found contradictory associations between a mother’s early sexual experience and her daughter’s experience.15 These studies have been done mostly among Whites and African American women.15 In the current study, childhood sexual experience is defined as at least one type of consensual sexual encounter (oral, vaginal, or anal) at the age of 15 years or younger. We hypothesized that childhood sexual activity, even if it was consensual, is associated with adult substance abuse if it occurred at the age of 15 years or younger, and this behavior is associated between mothers and daughters. Thus, the current study aims to investigate if Latina mothers’ early sexual experience and adult substance abuse is associated with similar behaviors among their daughters.

Among all intergenerational relationships, the mother–daughter relationship is very significant because mothers are important role models to their daughters. In fact, a study showed that a mother’s risky health behaviors were linked to her daughters but not to her sons.7 Literature supports that various maternal behavior problems can be transmitted to daughters.16,17 A mother’s experience of childhood sexual abuse has been suggested to be associated with her behavior and to her daughter’s likelihood of experiencing sexual abuse.17–19 Because of this association between the experience of sexual abuse across mother–daughter generations, a similar relationship for childhood sexual experience for mothers and their daughters is highly plausible. In accordance with the literature on the intergenerational transmission of problem behaviors,7,12,17,18 we hypothesized that maternal childhood sexual experience directly or indirectly influences her daughter’s childhood sexual experience as well as later substance abuse.

“Familism” among Latinos refers to family structures operating within an extended family system. It is believed to be the most important influence in the lives of Latinos.20 The affect of mothers’ experience and attitudes may be considerable to their daughters due to the strength of familial influence in Latino culture. Despite the strong family structure among Latino families, studies also show that Latina mother–daughters were least likely to discuss sex.20 This lack of discussion is often due to the fact that intrafamily conversations about sexual behavior are inherently taboo in the Latino culture.21 This study is significant in investigating the Latina daughter’s substance abuse in the context of intergenerational childhood sexual experience among mothers and daughters due to the pre-existing gap in the literature as well as the need to inform substance abuse and HIV/AIDS prevention programs. Adult Latinas are an underrepresented population in the substance abuse literature.22 Since the general Latino population and the number of Latino women who abuse illicit substances continues to increase in the US,23–25 this added knowledge on intergenerational transmission of childhood sexual experience will further inform health care professionals in the design of effective interventions to reduce childhood sexual experience and substance abuse among Latinas.

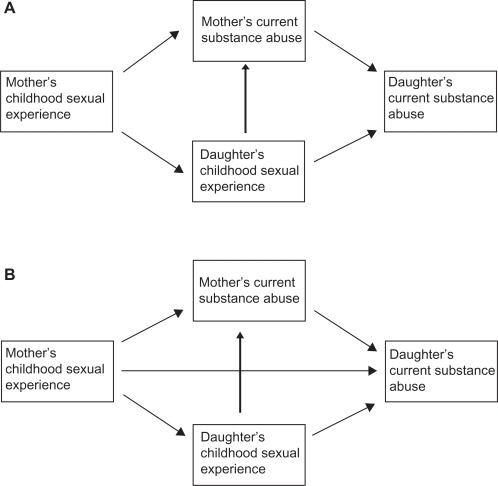

The purpose of the current study is to examine the relationship between early sexual experiences and substance abuse both within and across generations among a sample of Latina mothers and daughters. To test the direct and indirect effects of Latina mothers’ childhood sexual experience on their adult daughters’ substance abuse, we constructed two competing causal paths (Figure 1). Based on the findings of literature review, we included two paths: i) childhood sexual experience is associated with adult substance abuse among mothers and daughters, and ii) maternal childhood sexual experience and current adult substance abuse is associated with daughters’ childhood sexual experience and current adult substance abuse. In the path diagram, the single-headed arrows indicate “explanatory” variables to the “dependent” variables. The first path diagram (a) shows that a daughter’s current, adult substance abuse is indirectly related to her mother’s childhood sexual experience. The second path diagram (b) shows that daughters’ current substance abuse is also directly influenced by maternal childhood sexual experience.

Figure 1.

Two competing theoretical models on the relationship between mother’s early onset (aged 15 years or younger) of sexual activity and daughter’s drug use.

Methods

The current study was conducted with Latina mothers and daughters residing in Miami, Florida between 2004 and 2006. Prior to the interview, all participants learned the purpose of the study and then signed a written consent form. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of a large university reviewed and approved the current study.

Sample selection

Participants were recruited using the snow-ball sampling method and multiple outreach strategies. Participants were recruited through community fairs, health clinics, advertisements on local Spanish radio and television stations. Other successful recruiting methods were advertising in a local alternative newspaper, on an FM radio station, and via announcements at local drug court programs. Women were also recruited from community based substance abuse support groups such as Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). The general criteria for inclusion of Latino mothers and daughters in the study were: (a) consent to be interviewed for at least 2–3 hours, (b) aged 18 years or older, (c) identifying themselves as Latinas, (d) living in Miami–Dade County, Florida, and (e) willing to provide two telephone numbers where they could be reached during the study period. For the current study, both mother and daughter have never been sexually abused. As a result, all study participants currently in this analysis (92 dyads) have never reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse.

Instruments used in the questionnaire had been validated with minority populations and some were available in Spanish. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in the participants’ language of preference (either Spanish or English) by trained bilingual female interviewers. Eight master’s level female interviewers and two bachelor’s level female interviewers with backgrounds in social work, public health, psychology and nutrition conducted the interviews using a structured questionnaire. Mothers and daughters were interviewed separately and each individual interview took approximately 2–3 hours to complete. Interviews were scheduled at times and at locations convenient to participants such as their homes. A monetary incentive of $80 was provided to each mother–daughter dyad. Once the nonsubstance abuser participants quota was reached, noneligible dyads were rejected. Participation rate was high among dyads that were eligible for the study since there was a incentive referral system established as part of the recruitment strategies and in cases where a woman was unable to participate, the most common reason why was that she did not have a mother or daughter to form an eligible dyad.

Demographics

Demographic variables and descriptive variables were collected such as age, place of birth, education (> high school to college degree/graduate school) and employment (yes/no). Characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1. Age was measured as a continuous variable.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Total |

Daughter |

Mother |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | % | Size | % | |

| 92 | 100.0 | 92 | 100.0 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 years | 46 | 50.0% | ||

| 26–35 years | 23 | 25.0% | 2 | 2.2% |

| 36–45 years | 14 | 15.2% | 15 | 16.3% |

| 46–55 years | 9 | 9.8% | 38 | 41.3% |

| 56–65 years | 26 | 28.3% | ||

| 65+ years | 11 | 12.0% | ||

| Birth place | ||||

| US | 43 | 46.7% | 12 | 13.0% |

| Other country | 49 | 53.3% | 80 | 87.0% |

| Citizenship | ||||

| US | 59 | 64.1% | 51 | 55.4% |

| Other country | 33 | 35.9% | 41 | 44.6% |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 22 | 23.9% | 26 | 28.6% |

| High school | 17 | 18.5% | 22 | 24.2% |

| Some college | 37 | 40.2% | 21 | 23.1% |

| College degree | ||||

| Graduate | 16 | 17.4% | 22 | 24.2% |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 47 | 51.1% | 37 | 40.2% |

| No | 45 | 48.9% | 55 | 59.8% |

| Substance use | ||||

| Yes | 54 | 58.7% | 35 | 38.0% |

| No | 38 | 41.3% | 57 | 62.0% |

| Sexual experience as a child | ||||

| Yes | 38 | 41.3% | 18 | 19.6% |

| No | 54 | 58.7% | 74 | 80.4% |

Measure of current substance abuse

A participant was identified as a current substance abuser based on the frequency of alcohol, illicit drugs (marijuana, cocaine, heroin, ecstasy), or prescription drugs used during the last 12 months. The health and daily living (HDL) instrument was used to measure alcohol abuse. This instrument is composed of 12 indices that tap into two main areas of health functioning: (1) self-confidence and mood, and (2) extent of use and problematic substance use. The instrument was validated and considered reliable among a sample of 424 community adults and a sample of clinically depressed patients.26 The alcohol consumption section on Adult Form B was used for this study. The questions in this form elicit the usual amount of alcohol consumption (ie, alcohol quantity) using beverage-specific questions (ie, beer, wine, distilled liquors) and subsequent questions that assess how frequently participants consume alcohol (ie, answers ranged from never to everyday). For the purpose of the current study, alcohol abusers were defined in terms of at least one heavy drinking episode per month (adapted from Naimi and colleagues):27 at least 4–5 glasses of wine, 3–4 cans/bottles of beer, or 3–4 four-ounce drinks of hard liquor per occasion-during the 12 months prior to assessment.27

The drug use frequency scale (DUF)28 was used to assess the frequency of drug use among mothers and daughters.28 It assessed illicit drug use and prescribed drugs used without a doctor’s authorization (eg, sedatives) in the past 12 months. The DUF scale categorized frequency of drug use from 0 (never uses) to 8 (uses every day). Psychometric properties for this measure include its concurrent validity as having good agreement (0.87) with collateral reports of drug use frequency and with self-reports using the timeline follow-back measure (0.83–0.98).28 The current study utilizes drug use for the last 12 months. Mothers and daughters were classified as abusers of marijuana, cocaine, heroin, ecstasy, and/or prescription drugs. Illicit drug abusers were defined as participants who reported at least three days per week of marijuana use, two days per week of cocaine use, one or more occasions of heroin use per week, and/or at least three ecstasy use occasions per month during the 12 months prior to assessment. Abuse of prescribed medication was measured by asking participants whether they had taken medicine without a doctor’s authorization, in larger amounts than prescribed, or for longer periods than prescribed, in the 12 months prior to assessment (adapted from Turner and et al).29

Assessment of childhood sexual experience

The age at which participants’ first sexual experience occurred was obtained for each type of sexual encounter (How old were you the first time you had vaginal [or anal, oral] sex)? If participants reported at least one type of consensual sexual encounter at the age of 15 years or younger, they were eligible for our sample as an individual with a childhood sexual experience. We chose the term “childhood sexual experience” because our data does not permit us to know if the first sexual encounter was an isolated event or if it was indeed an onset of sexual activity. The age of the first sexual experience was categorized into three groups: i) childhood, defined as the age of 15 years or younger, ii) ages between16 and 19 years, and iii) 20 years or older.

Statistical analyses

Since measures from the mother and daughter are not independent (correlated dyad), each pair of mother–daughter data was entered as one unit of analysis. We aimed to explain the intergenerational association of childhood sexual experience as a risk factor for current substance abuse. Therefore, to select a path model most consistent with the pattern of correlations found in the data, we fitted two competing models using path analysis. Because our outcome variables were binary, a series of general linear models using a logit link and path estimates were calculated by maximum likelihood estimation.30 The best fitting of two models is evaluated based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The AIC methodology attempts to find the model that best explains the data with a minimum of free parameters. Data analyses were performed using the statistical packages, STATA version 10.031 and Mplus version 4.1.32

Results

Sample description and substance use for mother–daughter dyads

The average age of daughters was 29 years and ranged from 18 to 55 years. The average age of mothers was 54 years ranging from 33 to 88 years. Characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Participants were mainly of Cuban and Colombian descent. Approximately 13.0% of mothers and 46.7% of daughters were born in the US and a little more than half of the participants were US citizens (55.4% of mothers and 64.1% of daughters).

The education level of this sample was lower than that of the US. In 2007, 86% of all adults aged 25 years and older reported they had completed at least high school and 29% completed at least a bachelor’s degree in the US.33 However, among the mother participants in our study, only 71% had completed a high school or equivalent education and 24% had a bachelor’s or higher degree. Daughter participants also attained lower levels of high school education. Only 76% of daughter participants completed a high school or equivalent education. Since a daughter participant could be aged as young as 18 years, we could not compare the proportion of college degrees with the general population.

Nearly half of our study participants were categorized as a “substance abuser”. Approximately 58.7% of daughters and 38.0% of mothers were current substance abusers (Table 1). Substance abuse was correlated between mothers and daughters. If the mother was a substance abuser, then the daughter was more likely to be a substance abuser (OR = 2; P < 0.07).

Childhood sexual experience for mother–daughter dyads

The average ages of first sexual encounter for daughters and mothers were 16.1 and 18.3 years, respectively. On average, a daughter’s first sexual experience was at an age two years younger than that of her mother’s (paired t-test; P < 0.01). The first sexual experience occurred at ages as young as 8 years among daughters and 11 years among mothers. Approximately 88% of daughters and 91% of mothers reported that their first sexual encounter was vaginal sex with/without other types of sexual contact. The proportion of participants who had a childhood sexual experience among daughters and mothers were 41.3% and 19.6%, respectively. The difference between the two correlated proportions were statistically significant (McNemar’s test; P < 0.01).

Childhood sexual experience and substance abuse

Childhood sexual experience was a strong factor for current substance abuse among daughters. Daughters’ current substance abuse was associated independently with their own childhood sexual experience (OR = 6.0; P < 0.01). We further investigated the role of having first sexual contact as a late teenager (aged 16–19 years) versus at the age of 20 years or older on current substance abuse (Table 2). Compared with daughters who experienced sex at the age of 20 years or older, the odds of using a substance was 17.7 times higher (P < 0.01) among daughters with a childhood sexual experience and 3.8 times higher (P < 0.01) among daughters who first experienced sex during the ages of 16–19 years. Those who had their first sexual experience between the ages of 16–19 years (at the legal age of consent) were more likely to be current substance abusers compared to those who had it at the age of 20 years or older.

Table 2.

Age of having first sexual experience and current substance abuse as an adult

| Total |

Daughter |

Mother |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Substance abuse | Odds ratio | Total | Substance abuse | Odds ratio | |

| 92 | 54 (58.7%) | 92 | 35 (38.0%) | |||

| Age of first sexual experience | ||||||

| 15 years or younger | 38 | 31 (81.6%) | 17.7 | 18 | 10 (55.6%) | 3.3 |

| 16–19 years | 43 | 21 (48.8%) | 3.8 | 45 | 17 (37.8%) | 1.6 |

| 20 years or older | 10 | 2 (20.0%) | 1.0 | 29 | 8 (27.6%) | 1.0 |

Among mothers, childhood sexual experience was a risk factor for substance abuse as an adult as well (OR = 2.45; P < 0.05). Unlike what was seen among daughters, having their first sexual encounter as a late teenager was not a significant risk factor for current substance abuse among mothers. Compared with mothers who first experienced sex at the age of 20 years or older, the odds of using a substance was 3.3 times higher (P < 0.03) if a mother had childhood sexual experience, and 1.6 times higher (P < 0.18) if a mother first experienced sex during the ages of 16–19 years. Mothers who had their first sexual experience between the ages of 16–19 years (at legal age of consent) were not more likely to be current substance abusers compared to those who had it at the age of 20 years or older.

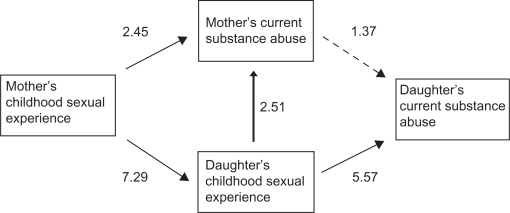

Intergenerational transmission of childhood sexual experience and drug use

We fitted two hypothetical models (Figure 1) to our data. We tested the competing models using the AIC method, which attempts to find the model that best explains the data with a minimum of free parameters. The best model is therefore the one with a smaller AIC value.34 Based on the AIC, we selected the first model (a), which fits our data slightly better: 353.5 for the first model (a), and 354.9 for the second model (b). This indicated that adding one more path did not improve the model. The path coefficients found in the logit model were exponentiated and presented as odds ratios in the selected model (Figure 2). Path analysis showed that mothers’ childhood sexual experience was not significantly associated with daughters’ current substance abuse. Rather, mothers’ childhood sexual experience contributed to daughters’ current substance abuse indirectly by increasing the risk of daughters’ childhood sexual experience. We reported previously that the daughter’s current substance abuse was associated independently with the mother’s current substance abuse (OR = 2.0; P < 0.07). However, when both characteristics were entered into the prediction model for daughters’ substance abuse, only daughters’ childhood sexual experience remained as a significant risk factor (OR = 5.57; P < 0.01). The affect of the mothers’ current substance abuse on the daughters’ current substance abuse became less important (OR = 1.37; P < 0.52) in the presence of the daughters’ own childhood sexual experience. The reason was, as shown in Figure 2, that both mothers’ current substance abuse and daughters’ childhood sexual experience were connected to mothers’ childhood sexual experience. Therefore, we concluded that the daughters’ childhood sexual experience was a strong risk factor for current substance abuse, which was also strongly predicted by the mother’s childhood sexual experience (OR= 7.29; P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Relationship between mother’s early onset (aged 15 years or younger) of sexual activity and daughter’s drug use.

Notes: All path coefficients shown were odds ratios. Solid line arrow indicates a statistically significant coefficient at alpha level of 0.05.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationships between mothers’ and daughters’ age of first sexual experience and adult substance abuse among Latinas in the US. Our study indicated several key findings with implications for substance abuse prevention efforts involving Latinas in the US. First, having sex as a child, even when it was a consensual act, was a strong predictor for later substance abuse. Additionally, although a mother’s adult substance abuse was a predictor for the daughter’s adult substance abuse, our study supported that the daughter’s own childhood sexual experience was a stronger factor for later substance abuse. This result suggests that guarding Latina girls from early sexual contact may have a protective effect against later adult substance abuse. Although our data are limited in answering the underlying emotional processes, we believe that sex could be an overwhelming experience for children, which could prevent them from dealing with normal developmental tasks including academic performance. Therefore, we conclude that interventions and educational efforts are needed to protect children from early sexual activity. Prevention programs may need to aim to educate young teens about negative outcomes of early sex in order to decrease the risks that early sexual activity may create.

Further, our study tested and confirmed a strong positive association between age of first sexual experience for mothers and their daughters. That is, if a mother experienced sex at an early age, then her daughter was likely to experience sex at an earlier age. While a causal link cannot be determined in the current cross sectional study, intergenerational transmission of sexual activity has been suggested to occur through a variety of mechanisms (environmental contributions) between mothers and daughters. Behavioral scientists often framed it within the context of social learning theory. According to social learning theory, most human behavior is learned observationally through modeling within a social context.35 Daughters often learn behaviors by modeling on their mothers and by sharing a similar environment. Although the sexual behavior is not learned through mother–daughter observation, the attitudes and level of knowledge are acquired through interactions with the mother, who is usually the primary care taker in Latino families. A previous study reported that the level of parental education explains the sexual behaviors of adolescents36 and this highlights the importance of family environment. Indeed some animal behavior studies concluded that intergenerational transmission of behaviors resulted from environmental contributions rather than genetic contributions.37 Therefore, intergenerational transmission of behaviors may be modifiable to some degree by implementing interventions targeting causal mechanisms indicated by future research.

The goal of prevention programs is to prevent or delay the onset of a problem among particularly high risk groups. If a woman had childhood sexual experience, then more intense protection is needed to guard her daughter from having childhood sexual experience. For instance, if a woman was identified as a mother who experienced childhood sex in any clinical setting, NA, or AA, a family-based prevention effort may need to be extended to the daughter to protect her from having sex at an earlier age. A study supported that parent education was a promising intervention for promoting early adolescent’s sexual abstinence.3 Education and intervention may include informing mothers about the detrimental effects of early sex as well as the potential nature of intergenerational transmission of childhood sexual experience. Along with education, empirically proven parenting skills can be taught as a part of family-based prevention programs.38–40 Since young girls have been found to be more likely to be a victim of unwanted sex,4,5 educating young daughters to protect themselves from unwanted sex may be a part of intervention. When the mother herself is at high risk and ill equipped to educate her daughter, providing intervention to both mother and daughter may be particularly beneficial. Extending prevention services to the daughters of high risk groups eventually would reduce economic burdens on the government and private insurance systems.

Further, findings revealed that the daughters’ first sexual experience occurred at an average age more than two years younger than the mothers’ first experience. It is noteworthy that the proportion of daughters who had sex as a child was also two times larger than that of mothers. This is consistent with a meta-analysis study41 suggesting that more people have become sexually active at an earlier age over the past generations. Although our database was limited to answering why daughters were having sex at younger ages than their mothers, we infer that it could be due to changes in culture, peer norms, and family structure. Additionally, for the mothers who were born outside of the US, the importance of maintaining their virginity before marriage in Latin culture42 may have influenced the later initiation of sexual activity (when compared to their daughters). Recently, the media has covered a surge in teen pregnancy at one particular high school where most of the pregnant girls were sophomores aged as young as 15 years.43 Their city mayor attributed the local spike in teenage pregnancies in part to a “popular culture that glorifies sex” and pointed out movies and media.44 While an increasing number of people acknowledge the role of media on teen’s decisions on sexual activity, changes in sexual behavior over generations is not well understood. Further study is needed to describe why more teenagers have become sexually active at an earlier age. Regardless, our study finding suggests that the education of human sexuality and its consequences should be offered to younger girls now more than ever before.

Another finding worthy of note is that having a first sexual experience as a late teenager (age between 16 and 19 years) compared to adulthood (age of 20 years or older) significantly elevated the likelihood of being a current substance abuser for daughters, although this was not replicated for mothers. Further study using larger samples and longitudinal data is needed to understand the moderating effect a woman’s generation has on her behavior. We contemplate the relative importance of education on socioeconomic status among the daughters’ generation compared to a mothers’ generation. Teenage girls engaging in sexual activity are reportedly less likely to graduate from high school or attend college.13 It may be that these sexually active youth also receive less education and experience a lower socioeconomic reality. The lowered socioeconomic status is then often linked with substance abuse.45

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Our study purposely over-sampled participants from the community who were abusing substances. Therefore, their background information is not necessarily compatible to that of the general public. This study sample was small and based on Latinas residing in Miami, Florida. Respondents consisted mainly of Cubans and other Latinas from Latin America (eg, Colombian and Venezuelans). Thus, the results may not be generalizable to other Latinas such as Mexicans. In an effort to secure a high enough number of substance abusers in our study, some of the participants were recruited from AA and NA meetings. Treatment-seekers are typically more severe cases. Additionally, the women who are participating in self-help programs may also indicate a greater than average desire to change their behaviors. Therefore, results from this study may not be generalizable to the general population as these women’s characteristics may not be the norm among women substance abusers. Another limitation of our study is that we relied on self-reported data. Due to social stigma, participants could have underreported their substance abuse and sexual activity as a child. Although we have no basis to believe that a longitudinal study would guard from underreporting, we believe that a longitudinal follow-up study would protect against recall bias.

Additionally, a longitudinal follow-up study involving potential co-varying risk factors such as parental psychopathology and parenting behaviors associated both with childhood sexual activity and substance-related problems in parents and their children would allow researchers to better describe causal mechanisms between early sexual experiences and lifetime substance abuse problems among mothers and daughters. We did not collect data on personality risk taking variables, which poses a limitation for the current study and could have helped explain if participants’ personality traits played a role in these Latino women’s risk health behaviors. We acknowledge that the path analysis itself is a correlation analysis and cannot test the direction of causation. Therefore, we used terminology of “prediction” rather than “causation”. However, our pre-specified causal path was built on causal paths found in the literature review. Additionally, our model maintained the temporal relationship in the intergenerational transmission framework and this enhanced the plausibility of the path, although it was limited to current substance abuse of Latina mothers and daughters. The assessment of a lifetime substance use problem would have allowed us to more accurately assess risk factors occurring earlier in life and, most importantly, during the daughters’ childhood. We recommend future longitudinal studies involving Latina substance abusing and non-substance abusing mothers to measure substance use rates and relationship quality with their daughters in early childhood. These variables should be measured over time to determine causal inferences about associations between maternal substance abuse and the development of daughters’ substance use disorders in the context of early sexual experience.

Conclusion

Our study supported the relevance of intergenerational association of having consensual sex as a child and substance abuse from mother to daughter. Mother and daughter childhood sexual experiences were highly correlated with current, adult substance abuse. Furthermore, the mothers’ childhood sexual experience were strongly related to that of their daughters. More importantly, the path between the mothers’ childhood sexual experience and the daughters’ current, adult substance abuse was interceded by the daughters’ childhood sexual experience. Therefore, our study suggests the need for further research to explore mothers’ childhood sexual experiences and its detrimental effects for their daughters.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number P20MD002288 from National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities and Award Number R24DA014260 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Arnaldo Gonzalez for his editorial assistance. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Ahmed J, Davis B, Gottman E, Payne H. Early onset of sexual activity: Implications in incarcerated women. J Correct Health Care. 2006;12:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brook D, Brook J, Pahl T, Montoya I. The longitudinal relationship between drug use and risky sexual behaviors among Columbian adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1101–1107. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell L, O’Donnell C, Stueve A. Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex related risks among urban minority youth: The reach for health study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:268–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manlove J, Moore K, Liechty J, Ikramullah E, Cottingham S. Sex Between young teens and older individuals: A demographic portrait. Washington, DC: Child Trends; 2009. Available from: http://www.childtrends.org/Files/StatRapeRB.pdf. Accessed July 13th, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanoss Marín B, Coyle KK, Gómez CA, Carvajal SC, Kirby DB. Older boyfriends and girlfriends increase risk of sexual initiation in young adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:409–418. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook J, Whiteman M, Zheng L. Intergenerational transmission of risks for problem behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:65–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1014283116104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickrama K, Conger R, Abraham T. Early adversity and later health: The intergenerational transmission of adversity through mental disorder and physical illness. J Gerontol. 2005;60B:125–129. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottschalk P. The intergenerational transmission of welfare participation: Facts and possible causes. J Policy Anal Manage. 1992;11:254–272. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey J, Hill K, Oesterle S, Hawkins D. Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generation. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orford J, Velleman R. The environmental intergenerational tansmission of alcool problems: A comparision of two hypotheses. Br J Med Psychol. 1991;64:189–200. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1991.tb01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornberry T, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte A, Krohn M, Smith C. Linked lives: the intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022574208366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20 year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rector R, Johnson K. Teenage sexual abstinence and academic achievement. Available from: http://www.heritage.org/Research/Abstinence/whitepaper10272005-1.cfm. Accessed July 13th, 2009.

- 14.Armour S, Haynie DL. Adolescent sexual debut and later delinquency. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Putman FG. Ten-year research update review: child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269–278. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin S, Burchinal M. Young women’s antisocial behavior and the later emotional and behavioral health of their children. Am J Public Health. 1992;8:1007–1010. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.7.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlap E, Sturzenhofecker G, Sanabria H, Johnson B. Mothers and daughters: The intergenerational reproduction of violence and drug use in home and street life. Journal of Ethnicity and Substance Abuse. 2004;3:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCloskey L, Bailey J. The intergenerational transmission of risk for child sexual abuse. Intergenerational Sexual Abuse. 2000;15:1019–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lev-Wiesel R. Intergenerational transmission of sexual abuse? Motherhood in the shadow of incest. J Child Sex Abus. 2006;15:75–101. doi: 10.1300/J070v15n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero AJ, Robinson TN, Haydel KF, Mendoza F, Killen JD. Associations among familism, language preference and education in Mexican-American mothers and their children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:34–40. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meneses L, Orrell-Valente J, Guendelman S, Oman D, Irwin C. Racial/ethnic differences in mother–daughter communication about sex. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Brown M. Coco’s World. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2004. Mama: Latina daughters celebrate their mothers; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alegria M, Page JB, Hansen H, et al. Improving drug treatment services for Hispanics: research gaps and scientific opportunities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(Suppl 1):S76–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compton W, Grant B, Colliver J, Glantz M, Stinson F. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant B, Dawson D, Stinson F, Chou S, Dufour M, Pickering R. The 12 month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billings A, Cronkite R, Moos R. Social-environmental factors in unipolar depression: Comparisons of depressed patients and nondepressed controls. J Abnorm Psychol. 1983;92:119–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad AH, Denny C, Serdula M, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Concurrent validity of a brief self-report drug use frequency measure. Addict Behav. 2003;28:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner BJ, Fleishman JA, Wenger N, et al. Effects of drug abuse and mental disorders on use and type of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:625–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. 4th edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. 5th edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Census Bureau US Census Bureau News 2009. Available from: http://www.census2010.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/education/011196.html. Accessed July 13th, 2009.

- 34.Kline RB. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd edition. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandura A, editor. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santelli J, Lowry R, Brener N, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1582–1588. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maestripieri D. Early experience affects the intergenerational transmission of infant abuse in rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9726–9729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R, Duran R, Jeanbaptiste V. Saving sex for later: An evaluation of a parent education intervention. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37:166–173. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.166.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dusenbury L. Family-based drug abuse prevention programs: A review. J Prim Prev. 2000;20:337–352. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etz K, Robertson E, Ashery R. Drug abuse prevention through family-based interventions: Future research. NIDA research Monograph. 1998;177:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells B, Twenge J. Changes in young people’s sexual behavior and attitutes, 1943–1999: A cross-temporal meta analysis. Rev Gen Psychol. 2005;9:249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espin O. Cultural and Historical Influences on Sexuality in Hispanic/Latin Women: Implications for psychotherapy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1997. Latina realities: Essays on healing, migration, and sexuality; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kingsbury K. Pregnancy boom at Gloucester high. New York, NY: Time Magazine; 2008. Jun 18, [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levenson M. Gloucester fields calls on teen pregnancies. 2008. Available from: http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/06/24/gloucester_fields_calls_on_teen_pregnancies/. Accessed July 13th, 2009.

- 45.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]