Abstract

Objective

To assess the current status of multi-campus colleges and schools of pharmacy within the United States.

Methods

Data on multi-campus programs, technology, communication, and opinions regarding benefits and challenges were collected from Web sites, e-mail, and phone interviews from all colleges and schools of pharmacy with students in class on more than 1 campus.

Results

Twenty schools and colleges of pharmacy (18 public and 2 private) had multi-campus programs; 16 ran parallel campuses and 4 ran sequential campuses. Most programs used synchronous delivery of classes. The most frequently reported reasons for establishing the multi-campus program were to have access to a hospital and/or medical campus and clinical resources located away from the main campus and to increase class size. Effectiveness of distance education technology was most often sited as a challenge.

Conclusion

About 20% of colleges and schools of pharmacy have multi-campus programs most often to facilitate access to clinical resources and to increase class size. These programs expand learning opportunities and face challenges related to technology, resources, and communication.

Keywords: multi-campus, distance education, administration

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy education has been in an era of expansion over the past decade, with class sizes increasing at many colleges and schools, new colleges and schools opening, and some existing programs adding distant campuses. The opening of multi-campus programs poses new issues related to accreditation, communication, distance education technology, and organizational structure and governance.

Generally, multi-campus programs provide distance education between campuses through the use of synchronous and asynchronous technology. Other technological advances in communication have facilitated rapidly changing models of pharmacy education. The multi-campus models have allowed the implementation of new programs, restructuring of learning environments, and even reshaping of student-student, student-teacher, and teacher-teacher interactions.

Typically, multi-campus programs are included under 1 accreditation awarded to the founding campus and administered by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). ACPE stipulates that these programs must meet current ACPE standards on each campus for curriculum, faculty support, student support, communication, interprofessional teamwork, outcomes, and many other factors.1 ACPE is still evaluating the need for changes in their standards for multi-campus colleges or schools of pharmacy.2

Reports in the pharmacy education literature describe distance education between campuses of the same college regarding technology and academic performance outcomes with varied findings. Several studies found no difference in performance outcomes between campuses. Nova Southeastern University (NSU), which uses compressed interactive video (CIV) technology between their campuses, found that student and faculty understanding of the roles and responsibilities of distant site facilitators, faculty members, and instructors was of utmost importance to successful CIV transmission.3 Furthermore, in NSU's pharmaceutics course, scores of students at the distant site were not significantly different from those of students at the main campus location.4 The authors/investigators recommended developing more interactive courses and better engaging students at the distant site.

Evaluation of the inaugural year of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy's satellite campus found no significant differences between students at the main and distant site in quiz or examination scores, cumulative grade point averages (GPAs), or introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) evaluations.5,6 The University of Florida conducted a similar study and found that students at their distant campus had a lower cumulative GPA in the first academic year. However, when consideration was given to academic preparation before entering pharmacy school, students performed equally well at each campus.7 Texas Tech University School of Pharmacy found no significant differences between local and distant site campuses in their pharmacotherapy course.8

Differences in academic performance between main and satellite campuses have also been reported. A study comparing the performance of students in a live classroom setting with students in an interactive videoconferencing group found the cohort in the live classroom setting had a significantly higher final course grade in a clinical pharmacokinetics course.9 Similarly, first- and second-year students at Creighton University in the distance campus pathway scored higher on performance-based assessments than students who completed the traditional campus-based pathway.10

As multi-campus education is a growing trend in pharmacy education, it is important to study developing models in order to understand the advantages and disadvantages, and provide information for other programs considering expansion so that subsequent program implementations may be more effective. We provide a comprehensive assessment of these new developments in pharmacy education (including technology and communication methods) and report on the current status of multi-campus programs in the United States.

METHODS

The Web site of each college and school of pharmacy in the United States accredited by ACPE was reviewed to determine whether it had more than 1 campus (at least 30 miles apart) within the same accredited program where first-, second-, or third-year PharmD students attended classes. Colleges and schools with students in class on more than 1 campus (excluding online classes and advanced pharmacy practice experience [APPE] sites) were considered multi-campus programs. A subset list was created that contained only the colleges and schools of pharmacy that had a multi-campus program.

A data collection tool with 24 questions regarding multi-campus colleges and schools of pharmacy was created and pilot tested. Questions on the survey instrument included date of inception of the multi-campus program; number of campuses within each multi-campus program; number of students per campus in each academic year; technology used to deliver curriculum between campuses; communication methods between collaborating faculty members at different campus locations; communication methods between faculty members and students at different campus locations; and communication methods between students at different campus locations. An Excel document was created that listed the colleges/schools with multi-campus programs and the questions from the data collection tool. Information that could be obtained from the college's or school's Web site was collected and entered in the Excel document, and then an administrative official at each college/school was called to confirm the data and provide any missing information or clarification.

Once the initial data gathering was complete, further inquiry was made to the same administrative officials at the colleges and schools with multi-campus programs to obtain responses to the following questions:

What was the reason (or reasons) for establishing your multi-campus program?

What are the major advantages or benefits of your multi-campus program?

What are the major problems or issues that you contend with in your multi-campus program?

Do you have any suggestions for other colleges considering expanding to a multi-campus program?

RESULTS

All accredited US colleges and schools were reviewed and data were obtained from 100% of colleges and schools with multi-campus programs. As of July 2009, 20 colleges and schools with multi-campus programs were identified. Eighteen of the 20 programs were public colleges or schools of pharmacy and over half were located in the South/Southeast.

Programs were classified into 2 subcategories of multi-campus schools: “parallel campus” and “sequential campus” programs. A parallel campus program had 2 or more campuses where students concurrently attended either or any (by choice or assignment) of the campuses and typically stayed at the same campus for the duration of the didactic portion of the curriculum. A sequential campus program had 2 or more campuses where all students went to 1 campus and then transferred to another campus location at some point during the didactic portion of the curriculum. Sixteen of the 20 programs with multi-campus programs were parallel campuses and 4 were sequential campuses.

Parallel Campus Programs

Of the 16 parallel campus programs; 11 had 2 campuses, 3 had 3 campuses, and 2 had 4 campuses. The range of the class size of the largest campuses was 75-165 students per class and the range of the class size of the smaller campuses was 10 to 90 per class.

Technology.

The method of curriculum delivery was primarily by synchronous transmission (12/16 schools). One college/school delivered its course content asynchronously and 3 schools delivered their course content as a hybrid of both synchronous and asynchronous. All colleges/schools reported their technology performed with little or no interruptions more than 90% of the time.

Eleven of the 12 parallel campus programs that delivered their curriculum content synchronously also recorded all lecture sessions. Of these 11 schools, 2 made the recorded content available to students immediately, 2 made the recorded content available within 24-48 hours, 2 made the content available only for emergency circumstances (such as a transmission problem), and 5 made the content available at the instructor's discretion. The program that taught its curriculum asynchronously made course content available within 1-2 hours after recording. Of the 3 programs using a hybrid delivery of curriculum transmission, 2 made their recorded content available the same day as the recording and the other did not record their material for future use.

Communication.

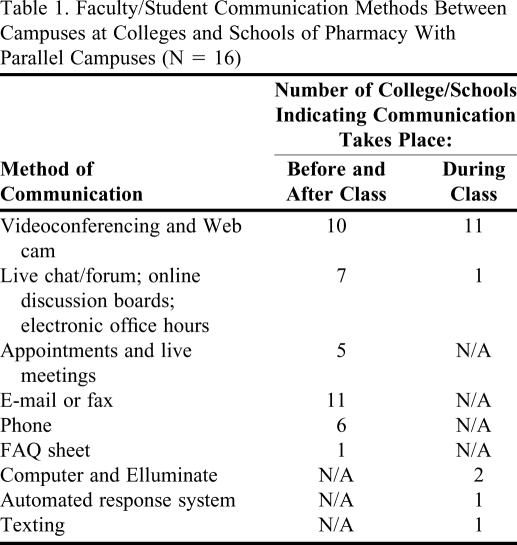

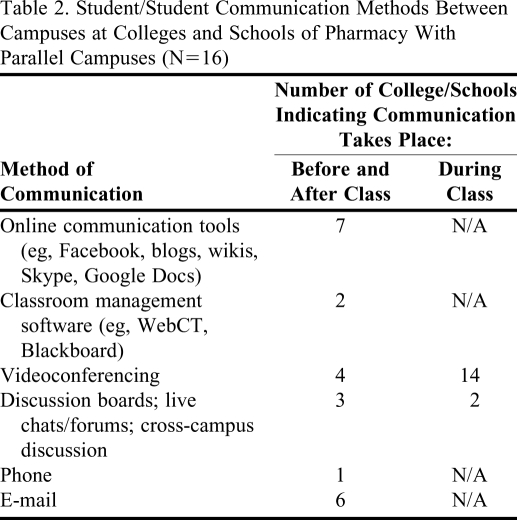

For parallel campus programs, details of the methods of communication that were used between faculty members and students at the campus locations before, during, and after class are provided in Table 1. Table 2 details the methods of communication that were used strictly between students at the various campus locations. Most programs used videoconferencing or Web cam technology. Almost half of the programs used live online chat rooms and forums, online discussion boards, and/or electronic office hours.

Table 1.

Faculty/Student Communication Methods Between Campuses at Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy With Parallel Campuses (N = 16)

Abbreviations: N/A = not applicable; FAQ = frequently asked question

Table 2.

Student/Student Communication Methods Between Campuses at Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy With Parallel Campuses (N=16)

Sequential Campus Programs

Of the 4 sequential campus programs, all had 2 campuses. Class size ranged from 70-115 students per class. All of the sequential campus schools taught classes at 1 site for a specific class year. None of the 4 programs recorded their curricular content.

Of the 4 sequential campus programs, 3 of them taught the first 2 years of the curriculum at 1 campus, and the third year at the second campus. In 1 of the 4 programs, students remained at the first campus for 2.5 years and then were transferred to the second campus for the second half of their third year.

Follow-Up Questions

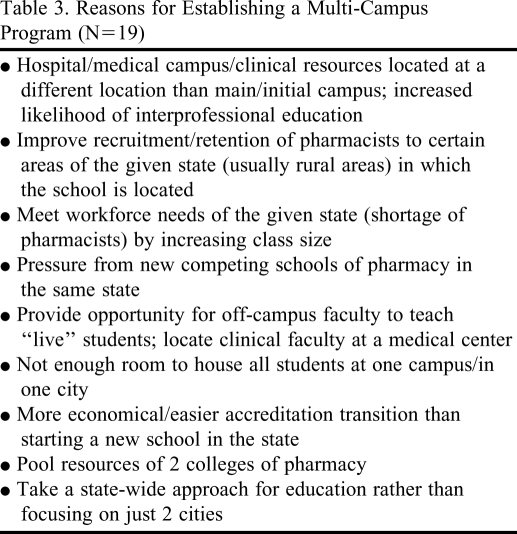

Reasons for Establishing a Multi-Campus Program.

Upon further questioning of the 20 multi-campus program officials, the most frequently stated reasons for establishing a multi-campus program included: a hospital and/or medical campus and clinical resources located at a different location than the main campus; increased likelihood of interprofessional education; improved recruitment and retention of pharmacists in certain areas of the given state (usually in rural areas) in which the college/school was located; and to meet workforce needs of the given state. A comprehensive list of reasons reported for establishing a multi-campus program can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reasons for Establishing a Multi-Campus Program (N=19)

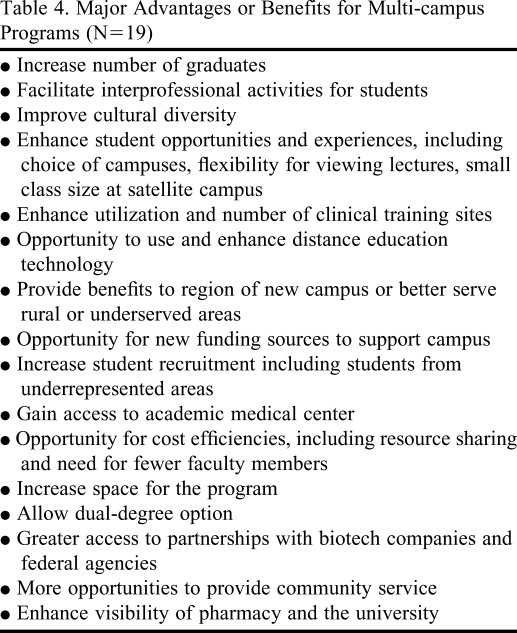

Major Advantages or Benefits for Multi-campus Programs.

The major advantages and benefits cited by the 20 programs for their multi-campus programs were that it: allowed expansion of the class size, facilitated interprofessional activities, improved cultural diversity, enhanced student opportunities and experiences (including choice of campuses, flexibility for viewing lectures, small class size at satellite campus), and enhanced utilization and number of clinical training sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Major Advantages or Benefits for Multi-campus Programs (N=19)

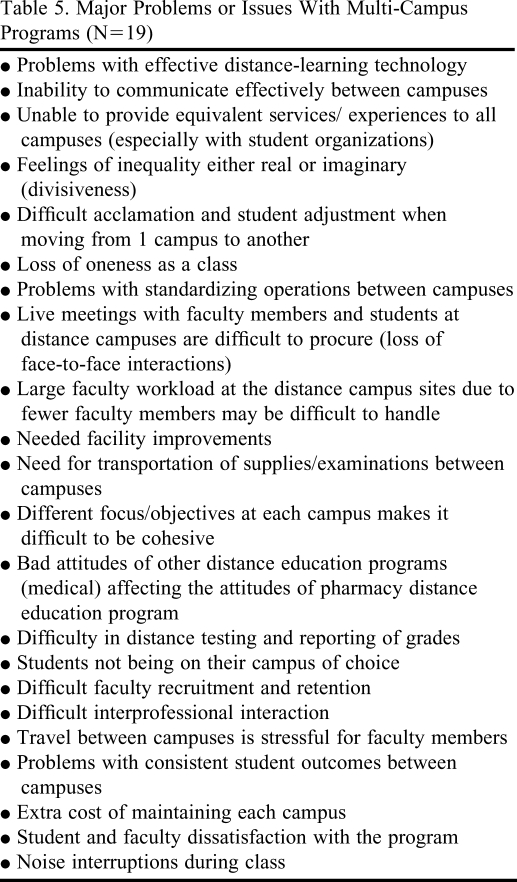

Major Problems or Issues with Multi-campus Programs.

The major problems or issues cited by more than 1 of the 20 colleges or schools of pharmacy for their multi-campus programs were: problems with effective distance education technology, difficulties in communicating effectively between campuses, difficulties in providing equivalent services or experiences to all campuses, division or feelings of inequality among students or faculty members; and difficulties in acclimating students when moving them from one campus to another (Table 5). There were many other issues reported by at least 1 program that referred to college operations, socialization, harmonization of policies, faculty workload, communication, transportation, faculty and staff recruitment, differences in student outcomes, expense, and a variety of program- and site-specific issues (Table 5).

Table 5.

Major Problems or Issues With Multi-Campus Programs (N=19)

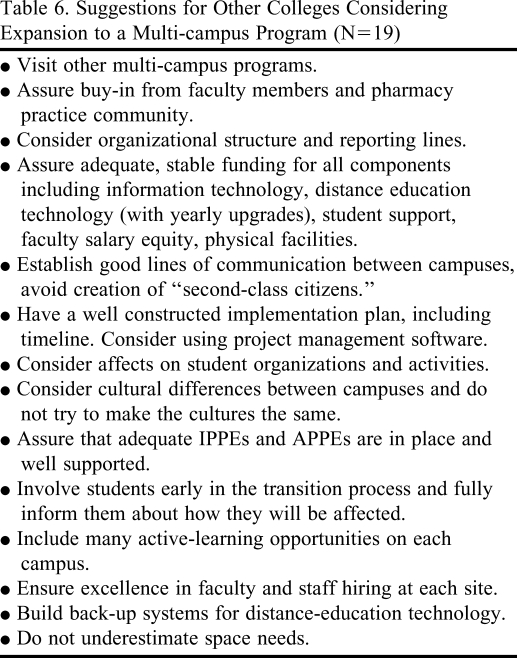

Suggestions for Other Colleges Considering Expansion to a Multi-campus Program.

The suggestions provided for other colleges/schools considering multi-campus expansion were far ranging and included consideration of funding, organizational structure, communication, technology, student organizations, cultural factors, practice experience sites, and faculty and staff hiring (Table 6).

Table 6.

Suggestions for Other Colleges Considering Expansion to a Multi-campus Program (N=19)

DISCUSSION

With the perceived pharmacist shortage in the United States, paired with the expanding number of prescription medications being dispensed, there is growing pressure on colleges and schools of pharmacy to produce more pharmacists. This trend is promoting an expansion of pharmacy colleges and schools across the country via addition of multi-campus programs.

Multi-campus colleges and schools now make up approximately 20% (20 of 106) of all colleges and schools of pharmacy. They are predominantly public colleges and over half are located in the South/Southeast. We did not collect information to determine why most multi-campus programs were at public colleges and schools. State budget reductions in recent years may have pushed these programs to develop enhanced revenue streams. Some universities may have additional resources to draw from to support multi-campus programs. Also, public colleges and schools may have a stronger mandate to serve other areas of their state. The authors learned of other colleges and schools that were planning to establish multi-campus programs in the future but did not include them.

Assessment of multi-campus programs becomes especially important and instrumental to uphold standards set by ACPE. ACPE standards state that distance-learning activities must have an evaluation plan that includes assessment between the campuses regarding comparability. The standards further state that colleges and schools “must ensure that workflow and communication among administration, faculty, staff, preceptors, and students engaged in the distance-learning activities are maintained” and “interaction of students across campuses be stimulated and encouraged.” Beyond in-school program assessment, ACPE recommends assessment through admission counselors to identify ideal candidates likely to be successful in a distance-education curriculum, including those students with self-motivation, commitment, and the necessary skills to perform well at a distance.1 We did not determine how well these surveyed programs met the ACPE standards or how well students performed on each of the campuses.

Technology (classroom, communication) is an important consideration for multi-campus programs. Although technology was reported to function well by more than 90% of respondents, many of those programs listed “problems with effective distance education technology” and “effective communication between campuses” as issues with multi-campus programs. Therefore, while the technology is working, it may not be working well enough. Given the rapid improvements in communication technology, these issues are likely to improve in the near future but may impose high costs. The quality of technology at the programs surveyed was not determined beyond the self-reports.

Colleges and schools cited a wide range of other issues with their multi-campus programs. While we recorded specific responses to identify major problems and issues, we did not investigate reasons for the responses. Also, while some institutions cited increased interprofesionalization as a reason for establishing a distant program, one program cited difficulties with interprofessionalization as a problem. These issues are clearly site specific.

Given the multiple locations at which faculty members and students attend class, communication between sites is typically a challenge and was one of the most frequently reported problems. Although there are many methods of communication available for distance-education programs, those using them must be effectively trained and have experience with the equipment in order for it to be optimally utilized by both students and faculty members. Having a member of the faculty or staff at each campus who is well versed in distance communication and technology may help tremendously. Initial and recurrent training sessions for all faculty members on new and existing technology can help them stay up-to-date on what communication options are available at their institution.

While some programs reported that cultural differences between campuses were important issues, there is no apparent generalizable approach to this issue. There are many types of academic cultures, at least those represented by large comprehensive universities, academic medical centers, large and small programs, research intensive and non-research intensive, as well as, the focus of the home university (such as religious affiliation or special population served).

The data presented in this report do not point to one particular multi-campus model that is superior to another. The design for a multi-campus program is best determined by the local factors, resources, and needs of the college/school. There are many other issues that were not addressed in this report such as the extra effort required by multi-campus programs and ACPE to achieve and maintain accreditation and the level of staffing required at distant campuses.

CONCLUSION

Twenty US colleges and schools of pharmacy have 2 or more campuses that utilize distance education in the first 3 years of the PharmD curriculum. Most of the colleges/schools started their multi-campus programs to have better access to clinical resources and to meet workforce needs by recruiting and retaining pharmacists in certain geographic locations. Although many programs had similar methods of communication and curriculum transmission, there were numerous differences in overall program delivery, indicating a need for education and information dissemination on the topic. The prevalence of multi-campus programs is likely to expand over the next several years, as colleges and schools strive to make better use of resources, expand class sizes, and better serve their region.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2010.

- 2.Robinson ET. Accreditation of distance education programs: a primer. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4) Article 95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy DH, Ward CT, Metzner MC. Distance education: using compressed interactive video technology for an entry-level doctor of pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4) Article 118. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mobley WC. Adaptation of a hypertext pharmaceutics course for videoconference-based distance education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(2):140–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knapp DA, Roffman DS, Cooper WJ. Growth of a pharmacy school through planning, cooperation and establishment of a satellite campus. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7306102. Article 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Congdon HB, Nutter DA, Charneski L, et al. Impact of hybrid delivery of education on student academic performance and the student experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(7) doi: 10.5688/aj7307121. Article 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid LD, McKenzie M. A preliminary report on the academic performance of pharmacy students in a distance education program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article 65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacLaughlin EJ, Supernaw RB, Howard KA. Impact of distance learning using videoconferenced technology on student performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article 58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kidd RS, Stamatakis MK. Comparison of students' performance in and satisfaction with a clinical pharmacokinetics course delivered live and by interactive videoconferencing. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(1) doi: 10.5688/aj700110. Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenz TL, Monaghan MS, Wilson AF, et al. Using performance-based assessments to evaluate parity between a campus and distance education pathway. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700490. Article 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]