Abstract

Objectives

To incorporate cultural competency concepts into various introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPE) at the University of Missouri - Kansas City, School of Pharmacy.

Design

A 6-week series, titled “Becoming a Culturally Competent Provider” was developed to provide IPPE students with the opportunity to apply theory regarding cultural competency in a clinical context.

Assessment

Pre- and post-intervention attitude survey instruments were administered to 25 students in the spring semester of 2009. Several activities within the series were associated with reflection exercises. Student presentations were evaluated and formal feedback was provided by faculty members. A course evaluation was administered to evaluate the series and determine areas of improvement.

Conclusion

A special series on cultural competency resulted in positive changes in students' attitudes, highlighting the importance of reinforcing cultural competency concepts during IPPEs.

Keywords: cultural competence, health disparities, socioeconomic status, experiential education, introductory pharmacy practice experience

INTRODUCTION

The United States is a rich amalgam of different cultures continually diversifying with immigration.1,2 The changing demographics of the United States population makes it all the more imperative to produce pharmacy graduates who not only are competent clinically but also able to function effectively within the context of culturally diverse populations.

Cultural competency has been at the forefront of pharmacy education for several years, with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) and Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) supporting the inclusion of cultural competency in the pharmacy curriculum.3,4 Proponents of cultural competency call for providing students with the knowledge and skills to establish adequate rapport with patients of a different backgrounds, thereby facilitating the provision of patient-centered care. Published articles in pharmacy, nursing, dentistry, and medicine have highlighted different models of instructional education in cultural competency.5-19 However, current published literature offers little guidance on the reinforcement of cultural competency concepts in a clinical setting. A few articles in the literature describe advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE) that serve a particular cultural population. Haack describes an APPE that exposed students to a predominantly Hispanic patient population.8 Patterson describes an APPE in public health which provided students with an opportunity to interact with uninsured and underinsured patients at the Kansas City Free Health Clinic.7 However, few published articles focus on reinforcing cultural competency concepts during IPPEs. Additionally, no published literature was found about pharmacy education experiences that reinforced cultural competency in clinical sites that do not serve any particular cultural group. Regardless of the patient demographic, cultural competency is important in all patient care encounters and should be reinforced throughout the curriculum, including clinical experiences in the acute care, ambulatory care, and community pharmacy settings. The importance of cultural competency in clinical settings is supported by the Joint Commission's proposed requirements to advance cultural competence as a requirement for accreditation.20

Acute care practice sites present a unique challenge that makes culturally-appropriate patient interaction especially difficult. Cioffi describes Australian nurses' experiences caring for culturally diverse populations in the hospital setting.21 While nurses valued the experience, they also found it challenging due to language barriers, different cultural requirements, and a reliance on a medical interpreter. On the other hand, Garrett and colleagues describe non-English-speaking patients' experiences in the acute care setting.22 Patients felt powerless as the language barriers presented a challenge for communication with their health care providers. Patients also felt that cultural norms were ignored on occasion, which led to a negative care experience.

Patients in the Veteran's Affairs hospitals and clinics also have specific cultural needs that must be considered to provide patient-centered care. Hobbs describes veterans as “a unique patient demographic” requiring specific interventions.23 The article highlights issues such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse, all of which can impact a patient's views about health and illness. This paper describes a pilot study reviewing the impact of a cultural competency series offered during an IPPE at an acute care teaching hospital and a Veteran's Affairs ambulatory care clinic.

The University of Missouri - Kansas City (UMKC) School of Pharmacy has a satellite campus in Columbia, Missouri, about 120 miles away from the Kansas City campus. The satellite campus has enrolled approximately 28 doctor of pharmacy (Pharm D) candidates for each academic year, with the potential to enroll 140 students distributed within the 5-year professional program. Missouri, according to the population census, has had a more homogenous population than the rest of the nation, which challenges natural exposure to various cultures.1 Columbia is a college town with a different population demographic than Kansas City. Kansas City is a large metropolitan city with a population of almost 1.5 million, in contrast to Columbia's 100,000. Population demographics also have differed, with the percentage of black persons being 31% in Kansas City versus 11% in Columbia. The percentage of the population with a minimum of a bachelor's degree is 26% in Kansas City versus 51% in Columbia.1

DESIGN

To provide the fundamental framework, cultural competency was introduced to the students in several instructional courses. Students received indepth instruction on cultural diversity, health literacy, and health disparities during the first few years of the curriculum. Students learned about Islamic beliefs in health care as a proxy of culturally competent care. In addition, they learned about caring for patients with mental illness and Alzheimer's disease. These lectures provided approximately 11 hours of instructional education in semesters 4 and 5 of a 10-semester curriculum.

Due to the differences in population demographics between Kansas City and Columbia, a 6-week series titled “Becoming a Cultural Competent Health Care Provider” was developed for distance students enrolled in IPPEs. Select students were assigned to either an inpatient adult medicine service or family medicine service within the University of Missouri Health System (UMHC). The remaining students were assigned to an ambulatory care clinic at Harry S. Truman Memorial Veteran's clinic.

The series provided students with opportunities to apply theory in a clinical context. Central to becoming culturally competent is becoming aware of one's own cultural beliefs, so self-reflection was also embedded in the series. The following outlines the format of the series.

Introductory Session

The objective of the introductory session was to describe the current United States population demographics and how it is projected to change over time, and to describe the impact of language barriers, religious background, and ethnicity on patients' health beliefs. The time required was 2 hours.

During the first part of this session, a faculty member provided an overview of the population demographics, health disparities, cultural differences, language barriers, religious beliefs, and alternative medicine including shamanism, ayurvedic medicine, and traditional healers in the United States. The last part of this session consisted of an interactive discussion forum that allowed students to share their personal biases and opinions regarding cultural diversity. Students also were asked to share their “first memory of differences.”24,25 At the end of the session, students were asked to pay particular attention to the cultural needs of the patients they encountered during IPPEs and to write a 1-page reflection piece on this topic, due at the end of the series.

Patient Care Scenarios

The objective of the patient care scenarios was to demonstrate how to conduct cross-cultural clinical encounters by using various communication models. The time required was 2 hours. This session provided students with the opportunity to apply various communication models to elicit the patient's view on health. As a prelude to the activity, a brief clip from a popular television show, Grey's Anatomy26 was shown to the students. The 5-minute clip involved a Hmong patient diagnosed with a brain tumor. When advised to undergo brain surgery, the patient's father insisted on taking her home. Upon further communication, her physicians realized that her family believed she had lost 1 of her souls, and that without a shamanic ritual her soul would never be restored.

After watching the Grey's Anatomy video clip, students were asked to reflect as a group on the following questions about the video: (1) What was your first impression when you saw the video? (2) What did you think of the father's decision to take the patient home? (3) Do you agree with the family's request to complete the shamanic ritual before proceeding with the surgery? (4) How did the doctor handle the conversation with the family? (5) What attributes of the physician's attitude set the family at ease and allowed them to proceed with the surgery? (6) Would you have handled the case differently if faced with a similar situation?

After 30 minutes of discussion, a faculty member delivered a brief lecture on Kleinman's questions and the “LEARN” and “BATHE” communication models designed to provide clinicians with the tools to communicate effectively with a patient of a different background.27-29 The questions included are nonjudgmental and provide a framework that allows the provider to understand the patient's view about health, illness, and medications. Kleinman suggested that using tactful questions to elicit health beliefs puts the patient at ease and opens lines of communication. These communication models also allow the provider to view the patient as a unique entity and thereby avoid the pitfalls of stereotyping.

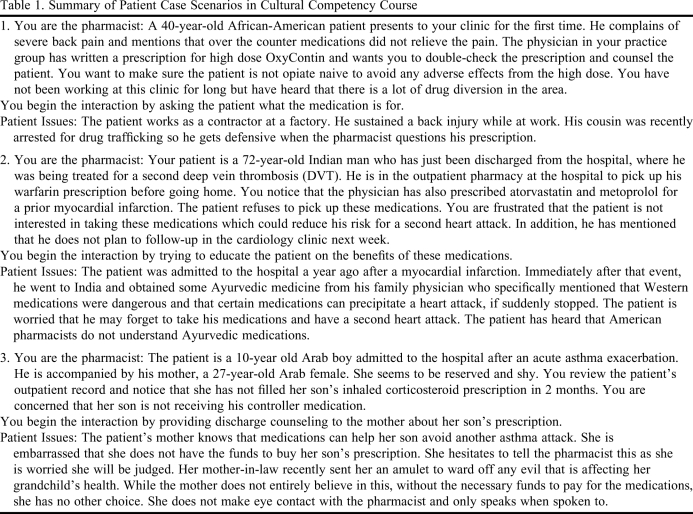

After this lecture, students were asked to counsel a patient and use the communication models discussed. Groups of 3 students were selected and provided a case vignette (Table 1). Each student had the opportunity to serve as the pharmacist, patient, and observer. Observers were instructed to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the pharmacist's interactions with the patient. The cases were developed to allow students to understand that there is diversity among cultures and that stereotypes can lead to errors in interpretation. In each case, the patient was asked to display body language that could have been misinterpreted. For example, the lack of eye contact from an Arab woman could have been misconstrued by the student as shyness or rude behavior, or a cultural stereotype of Arab women being submissive, when in fact the lack of eye contact was due to embarrassment over insufficient finances to pay for her child's medications. Cases were created that would defy cultural stereotypes and compel the student to elicit the patient's health beliefs. After the exercise, discussion allowed students to reflect on their performance as well as the challenges faced while caring for the patient.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Case Scenarios in Cultural Competency Course

Religious Forum

The objective of the religious forum was to identify religious factors that impact health care decisions. The time required was 2 hours. This session was designed to provide students with pertinent information on various religions. Representatives from Islam, Judaism, Baha'ism, Hinduism, and an indigenous African religion were invited to participate in a 2-hour interactive forum discussing religion and health care. Students were informed that this activity was designed to provide a forum for free speech, and they could ask these religious leaders/experts any questions relevant to the session. The representatives were asked to focus on the following questions so that the discussion remained within the context of health care:

How do religious beliefs affect health?

Do followers believe in modern medicine?

Are there any considerations with respect to physical touch or physical examination?

Do female patients have any reservations with male health care providers?

Are there any considerations with regard to blood or pork products?

Do families consult religious leaders prior to therapy?

Are health beliefs ingrained with traditional healers or folk medicine?

In addition to the discussion forum, students also received a brief handout that covered religions of the East and West, including Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism, Mormonism, and Roman Catholicism. The handout, created by faculty members, provided information regarding each religion's philosophy concerning: (1) health and well-being; (2) dietary restrictions; (3) use of traditional or herbal medicines; (4) treatments or medications that are refused by the followers of the religion; (5) blood transfusions; (6) organ transplant/organ donation; (7) sexual enhancement drugs (eg, sildenafil); (8) birth control; and (9) abortion. (Handout available upon request from the authors.)

At the end of the session, students were asked to write a 1-page reflection on several points including:

Does religion shape your own health beliefs? Please explain.

Do you have any religious/spiritual beliefs that could conflict with your role as a pharmacist? If so, how do you plan to resolve those conflicts? (eg, dispensing emergency contraception pills)

Do you think understanding your patient's religious background may help you provide better care for your patient? Please explain your answer.

These reflection questions were used to generate introspection regarding the student's own religious beliefs as well as any biases affecting the student's perceptions of their patients.

Socioeconomic Session

The objective of the socioeconomic session was to identify financial barriers to medication acquisition and propose solutions to overcome these barriers based on individual patient factors. The time required was 2 hours.

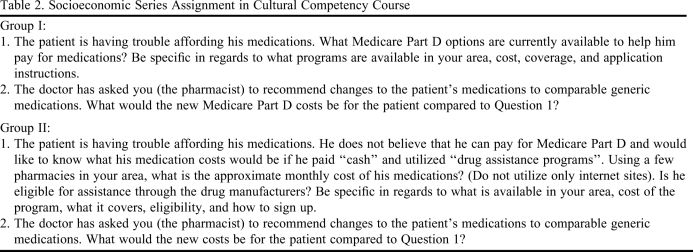

Prior to this session, students had attended either multidisciplinary rounds and interacted with a medication assistance specialist at the UMHC or interacted with a social worker/case manager in charge of medication assistance at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans' Hospital. Students also received indepth information regarding patient assistance programs available through pharmaceutical companies. These experiences were designed to highlight the challenges in medication acquisition for uninsured or underinsured patients. In the prior session, each student had received a case vignette highlighting a patient's socioeconomic status as well as a comprehensive patient history (cases available upon request from the authors). Students were divided into 2 groups: group I was instructed that the patient was eligible for Medicare Part D, while group II was instructed that the patient did not want to pay for Medicare Part D and instead preferred to pay cash or apply for patient assistance programs.30 The assignment is summarized in Table 2. The students were instructed to complete a financial analysis including their patient's current medication cost and when the patient would reach the Medicare coverage gap and catastrophic coverage (group I), as well as the financial impact of a therapeutic substitution to a less expensive generic alternative. Each student was asked to provide a 5-minute formal presentation of his/her analysis to the group.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic Series Assignment in Cultural Competency Course

At the end of the session, students were asked to write a 1-page reflection on several points including:

Group I: If you were a “lay person,” what barriers would you encounter while signing up for select insurance plans through Medicare Part D?

Group II: How easy was it for you to find medication assistance for your patient?

Health disparities

The objective was to discuss disparities in health care affecting various minority groups and develop solutions for providing care to these groups. The time required was 6.25 hours.

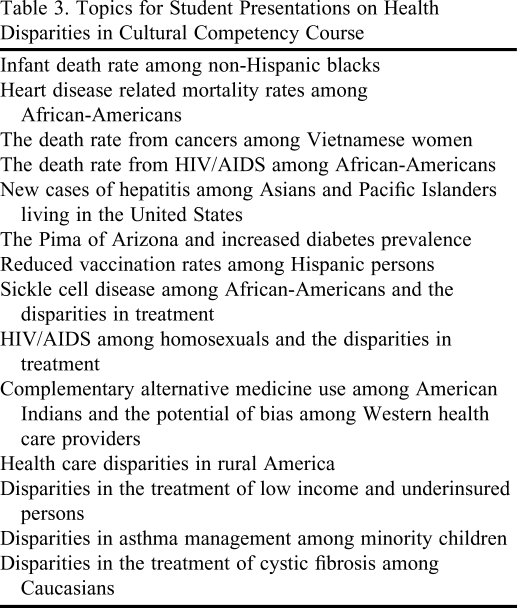

Each student was assigned a health disparity (Table 3) and instructed to provide a 15- minute presentation highlighting the disparity, the cost to the health care system, and the implication to patient-centered care. The exact definition of each health disparity was open for interpretation by the individual student. Students also were asked to develop practical strategies to reach out to their specific cultural group. The faculty members chose health disparities that would augment the students' learning as well as have real life implications on pharmacy practice.

Table 3.

Topics for Student Presentations on Health Disparities in Cultural Competency Course

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Curriculum Evaluation

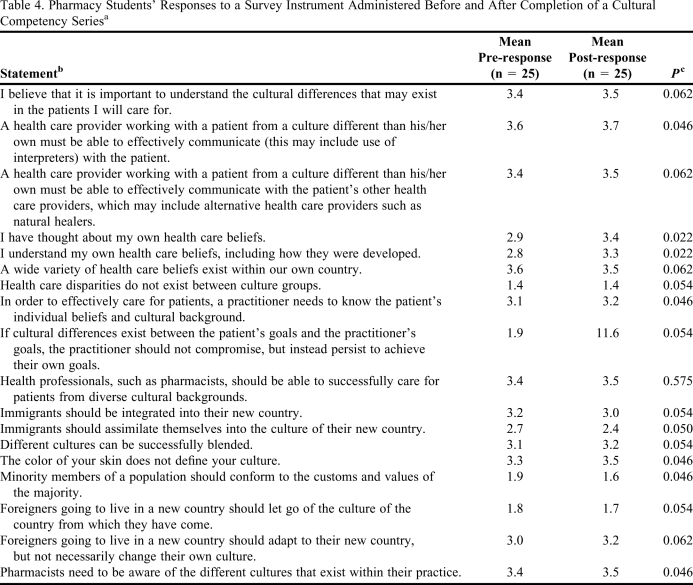

The assessment component was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at UMKC. Because students had received several lectures on cultural competency which would have had an impact on their attitudes, a pretest adapted from Westberg et al and Dogra was administered to determine the students' attitudes regarding cultural competency prior to this series.13,19 At the end of the series, the same instrument was administered to detect changes in attitudes. Reflection pieces provided informal feedback regarding students' attitudes on various culturally relevant topics as well as areas for future focus. A course evaluation also was administered which measured student satisfaction with each component of the series.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC). Data from the pre- and post-attitude survey instruments were matched by deidentified student codes. The Wilcoxon rank test was used to analyze ordinal data from the attitude survey instruments. Adjusted p values of ≤ 0.01 were considered significant.

Learner Evaluation

Student performance on the patient scenarios was evaluated by the student “observer” who answered various questions about the “pharmacist's” performance. Students also received summative feedback from faculty members who noted any strengths and weaknesses in the students' interactions with various patients during their performance. Students' presentations on health disparities were evaluated by faculty members and student peers and written feedback was provided.

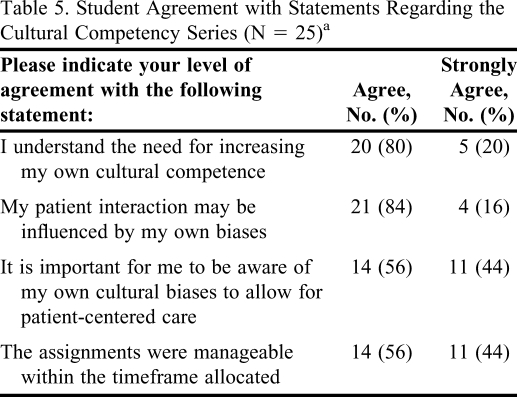

Twenty-five students completed the cultural competency series during the spring 2009 semester. Of these, 88% were born in the United States, 12% spoke a language besides English, which was learned either in high school or college, and 76% had lived in another country. Pre- and post-attitude survey results showed significant changes in 8 out of 18 items (Table 4). Students were more aware of their own health beliefs after the series (p < 0.022). There was also a significant change in attitudes regarding the need for pharmacists to be aware of the different cultures within their practice (p < 0.046). All students either agreed or strongly agreed that there was a need for increasing their own cultural competence and that their patient interaction might be influenced by their own biases (Table 5). Reflections on the socioeconomic series revealed that the majority of the students (90%) had not realized how difficult it is to navigate through the Medicare Part D Web site. They felt that their elderly patients would not be able to find an appropriate plan without help from a health care provider or caregiver. Of interest, 50% of students mentioned that while community pharmacists are in a unique position to assist patients with determining the best Medicare plan, most community pharmacists have a heavy workload and cannot accommodate a large number of requests from patients. On average, students saved their patient at least $750 per year by substituting the patient's medication with less expensive generics and by identifying patient assistance programs.

Table 4.

Pharmacy Students' Responses to a Survey Instrument Administered Before and After Completion of a Cultural Competency Seriesa

Student responses based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 on which 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree.

bStatements adapted from Westberg and Dogra.

cWilcoxon rank test.

Table 5.

Student Agreement with Statements Regarding the Cultural Competency Series (N = 25)a

Response options ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree; however, there were no responses of strongly disagree or disagree.

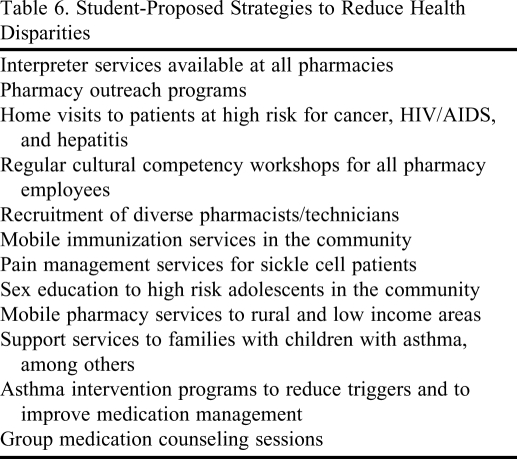

A general trend in the reflection pieces about the religious forum revealed that a large number of students (80%) felt a sense of dissonance between their religious beliefs and their responsibility as a health care provider. Some students (30%) mentioned that they would not dispense emergency contraception as it was against their religious beliefs, but would make arrangements to have another pharmacist dispense the drug. The majority of students (85%) agreed that understanding a patient's religious background is an important step to eliciting their health beliefs. Several students commented that they knew very little about the religions of the world and were surprised to learn about the Baha'i religion in particular. They all felt it was important for a pharmacist to recognize the existence of various religions as well religion's impact on health care. Student-proposed strategies to reduce health disparities are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Student-Proposed Strategies to Reduce Health Disparities

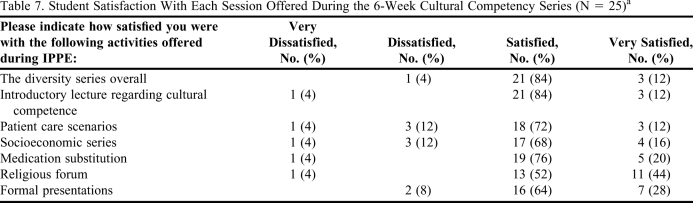

Course evaluations revealed that a majority of students were satisfied with the components of the series (Table 7). Ninety-two percent of students enjoyed the various activities offered during IPPEs; 92% agreed or strongly agreed that the cultural competency series helped them identify the various disparities in health care; and 92% agreed or strongly agreed that cultural competency is an important component of the PharmD curriculum. All students stated that the series should be offered each year during IPPEs.

Table 7.

Student Satisfaction With Each Session Offered During the 6-Week Cultural Competency Series (N = 25)a

Student responses based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4. 1 = very dissatisfied, 4 = very satisfied.

DISCUSSION

This series was developed to reinforce cultural competency during IPPEs. It was designed to augment the fundamental concepts that instructional coursework had offered in prior years. Faculty members felt this was imperative prior to the students beginning their APPE sessions, as it would create the awareness that providing quality care requires an understanding of the patient's cultural beliefs in addition to excellent clinical knowledge. Increasing the students' awareness of their own health beliefs was one of the goals of the exercise as it is important for students first to understand their own cultural beliefs prior to attempting to understand their patients' beliefs. At the end of the series, all students felt that pharmacists need to be aware of the different cultures that exist within their practice. Pharmacists may be able to provide better, culturally competent care if they take measures to determine the cultural landscape of the communities they serve. Course evaluations showed that some students ranked the socioeconomic exercise lower than the other activities. A number of students commented that the socioeconomic exercise was time consuming and required too much groundwork. While this may have affected the evaluation, faculty members felt that it was vital that students understand the complexity of the Medicare Part D Web site to create the impetus to offer those services in the future.

There were limitations to the series, including students role-playing as the patient in the patient care scenarios. The scenarios would have been more effective with real or simulated patients. Another limitation was the short duration of the series, which did not facilitate indepth discussion about culture and health. Additionally, the study did not determine the long-term impact of the cultural competency series, which would have provided useful information regarding sustainability of the attitude changes seen in the short term. Readministering the survey instrument prior to graduation might provide some long-term outcomes data.

The faculty plans to offer this series every spring semester prior to the beginning of APPEs. Based on student feedback about the patient scenarios, in the future, the Russell D. and Mary B. Shelden Clinical Simulation Center at the University of Missouri will be used for activities. This will allow the faculty to simulate patients from various cultures to provide a more realistic environment for the patient scenarios.

CONCLUSION

This cultural competency series offered during IPPEs was well received. Students enjoyed the various activities, and the positive changes in student attitudes towards cultural competency highlighted the need for continued reinforcement of these concepts during clinical experiences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Nicole Lee, PharmD, for her assistance with the conception of this study; Dr. Cameron Lindsey, PharmD, BC-ADM, for her assistance with the statistical analysis of the pre- and post-survey instrument questions; and Drs. Patricia Marken, PharmD, FCCP, BCPP; and Erica Russell, PharmD, for editing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. US Census Bureau. USA Quick Facts. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- 2. Camarota SA. Immigrants in the United States, 2007: A profile of America's foreign-born population. http://www.cis.org/immigrants_profile_2007. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- 3. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2010.

- 4. CAPE Educational Outcomes, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/documents/CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- 5.Poirier T, Butler L, Devraj R, Gupchup G, Santanello C, Lynch JC. A cultural competency course for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;(5):73. doi: 10.5688/aj730581. Article 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green AR, Betancourt JR, Park ER, Greer JA, Donahue EJ, Weissman JS. Providing culturally competent care: residents in HRSA Title VII funded residency programs feel better prepared. Acad Med. 2008;83(11):1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181890b16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson BY. An advanced pharmacy practice experience in public health. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205125. Article 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haack S. Engaging pharmacy students with diverse patient populations to improve cultural competence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205124. Article 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner J, Arteaga S, D'Ambrosio J, et al. Dental students' attitudes toward treating diverse patients: effects of a cross-cultural patient-instructor program. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(10):1128–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onyoni EM, Ives TJ. Assessing implementation of cultural competency content in the curricula of colleges of pharmacy in the United States and Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710224. Article 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown B, Heaton P, Wall A. A service-learning elective to promote enhanced understanding of civic, cultural, and social issues and health disparities in pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1) doi: 10.5688/aj710109. Article 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaya FT, Gbarayor CM. The case for cultural competence in health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7006124. Article 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westberg SM, Bumgardner MA, Lind PR. Enhancing cultural competency in a college of pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5) Article 82. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assemi M, Cullander C, Hudmon KS. Implementation and evaluation of cultural competency training for pharmacy students. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(5):781–786. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah MB, King S, Patel AS. Intercultural disposition and communication competence of future pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(5) Article 111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva MA, Nolan NM, Tataronis GR. Pharmacy students' baseline perceptions of cultural diversity prior to advanced pharmacy practice experience. ASHP Midyear Clinical Meeting. 2004 39P96E. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tervalon M. Components of culture in health for medical students' education. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):570–576. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):560–569. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dogra N. The development and evaluation of a program to teach cultural diversity to medical undergraduate students. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):232–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Joint Commission. Developing Proposed Requirements to Advance Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient-Centered Care for the Hospital Accreditation Program. http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/HLC/HLC_Develop_Culturally_Competent_Pt_Centered_Stds.htm. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- 21.Cioffi J. Nurses' experiences of caring for culturally diverse patients in an acute care setting. Contemp Nurse. 2005;20(1):78–86. doi: 10.5172/conu.20.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrett PW, Dickson HG, Whelan AK, Roberto-Forero What do non-English-speaking patients value in acute care? Cultural competency from the patient's perspective: a qualitative study. Ethn Health. 2008;13(5):479–496. doi: 10.1080/13557850802035236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobbs K. Reflections on the culture of veterans. Am Assoc Occup Health Nurse J. 2008;56(8):337–341. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20080801-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welch M. Teaching Diversity and Cross-Cultural Competence in Health Care: A Trainer's Guide. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Perspectives of Differences Diversity Training and Consultation Services for Health Professionals (PODSDT); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Assemi M, Cullander C. Cultural Competency in Pharmaceutical Care Delivery: A Training Template for a One-Day Pharmacy Student Elective Course. San Francisco, CA: Center for the Health Professions, University of California, San Francisco; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rhimes S, Tinker M. “Bring the pain.” Grey's Anatomy. ABC television. October 23, 2005.

- 27.Stuart MR, Lieberman JA. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Practical Therapeutic Interventions in Primary Care. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinman A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berlin EA, Fowkes WC., Jr A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care – application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139(6):934–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. The Official United States Government Site for People with Medicare. US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.medicare.gov. Accessed July 20, 2010.