Abstract

The dynamics, computational power, and strength of neural circuits are essential for encoding and processing information in the CNS and rely on short and long forms of synaptic plasticity. In a model system, residual calcium (Ca2+) in presynaptic terminals can act through neuronal Ca2+ sensor proteins to cause Ca2+-dependent facilitation (CDF) of P/Q-type channels and induce short-term synaptic facilitation. However, whether this is a general mechanism of plasticity at intact central synapses and whether mutations associated with human disease affect this process have not been described to our knowledge. In this report, we find that, in both exogenous and native preparations, gain-of-function missense mutations underlying Familial Hemiplegic Migraine type 1 (FHM-1) occlude CDF of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. In FHM-1 mutant mice, the alteration of P/Q-type channel CDF correlates with reduced short-term synaptic facilitation at cerebellar parallel fiber-to-Purkinje cell synapses. Two-photon imaging suggests that P/Q-type channels at parallel fiber terminals in FHM-1 mice are in a basally facilitated state. Overall, the results provide evidence that FHM-1 mutations directly affect both P/Q-type channel CDF and synaptic plasticity and that together likely contribute toward the pathophysiology underlying FHM-1. The findings also suggest that P/Q-type channel CDF is an important mechanism required for normal synaptic plasticity at a fast synapse in the mammalian CNS.

Keywords: Cav2.1, familial hemiplegic migraine type 1, CACNA1A, calmodulin

Short-term facilitation of synaptic release has historically been attributed to enhanced vesicle release resulting from the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ in presynaptic terminals during repetitive action potentials (APs), in which the buildup of residual Ca2+ enhances binding to sensor proteins that directly mediate vesicle fusion and transmitter release. Short-term depression of synaptic release has been traditionally accredited to vesicle depletion (1). However, at the large calyx of Held synapse, it has been shown that short-term synaptic plasticity is also achieved by a mechanism involving the regulation of presynaptic P/Q-type Ca2+ currents (2–4). Further, a recent study using recombinant P/Q-type channels expressed in cultured superior cervical ganglion neurons demonstrated that the Ca2+-dependent facilitation (CDF) and Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) of P/Q-type channels are mediated through neuronal Ca2+ sensor proteins (CaSs) that bind the P/Q-type Cav2.1 subunit carboxyl terminus and induce short-term synaptic facilitation and rapid synaptic depression, respectively (5). Whether similar forms of CDF and/or CDI of P/Q-type channels are affected by mutations associated with human disease and whether these modulatory mechanisms represent crucial components of synaptic plasticity at typical intact central synapses have not been described to our knowledge.

In the current study, we explored the effects of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine type 1 (FHM-1) missense mutations on calmodulin (CaM)-mediated CDF and CDI of the P/Q-type channel. FHM-1 is an autosomal dominant form of migraine with aura, typified by hemiparesis and linked to missense mutations in the CACNA1A gene encoding the P/Q-type Cav2.1 α1 subunit (6). Biophysically, FHM-1 missense mutations result in an overall gain-of-function P/Q-type channel phenotype as a result of an underlying shift in channel gating allowing increased Ca2+ influx at lower membrane potentials (7, 8). CaM-mediated CDF and CDI are robust forms of P/Q-type channel modulation in which CaM interacts with the Cav2.1 carboxyl terminus in a bipartite regulatory processes; CDF is mediated by a local increase in Ca2+ and CDI through a global increase in Ca2+ (4, 9–17). The underlying mechanisms of these forms of CDF and CDI are also attributed to changes in channel gating (10), and it was of interest to examine whether FHM-1 mutations affect these important modulatory properties of P/Q-type channels and to explore physiological implications by using transgenic models.

We find that FHM-1 gain-of-function missense mutations significantly occlude CDF in recombinant and native systems and correlate with a reduction in short-term synaptic facilitation. Collectively, the data support the notion that selective Ca2+-dependent regulation of presynaptic Ca2+ channels may underlie several key aspects of short-term plasticity at the parallel fiber-to-Purkinje cell (PF–PC) synapse in cerebellum, and also provide evidence that FHM-1 mutations directly affect the Ca2+-dependent regulation of P/Q-type channels (Fig. S1 shows the proposed model).

Results

FHM-1 Mutations Occlude CDF and CDI of Recombinant Human Cav2.1 Channels.

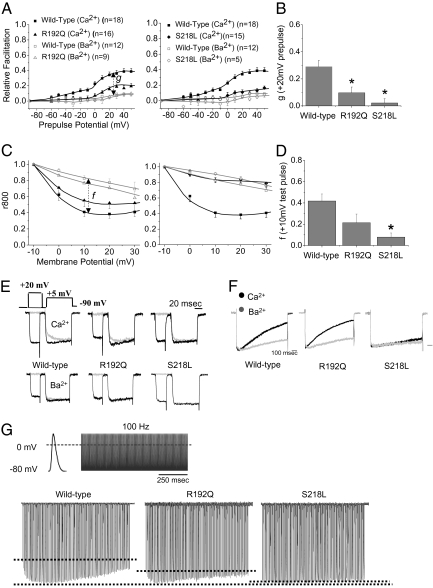

Human recombinant Cav2.1 channels transiently expressed in HEK cells (along with auxiliary subunits β2a and α2δ) is a well characterized system and allows for clear isolation and measurement of CaM-mediated CDF and CDI (12, 13). Consistent with previous findings, WT Cav2.1 channels showed typical CDF with prepulse-dependent facilitation when Ca2+ was used as the charge carrier (Fig. 1A, black squares). During a test pulse, Cav2.1 channels showed a rapid initial activation and then slowly transitioned to a facilitated mode as Ca2+ entered (Fig. 1E, gray traces). In contrast, an applied prepulse evoked Ca2+ entry increasing the fractional portion of channels in a facilitated mode of gating such that, during an ensuing test pulse, channels exhibited fast activation indicative of the facilitated gating state [Fig. 1E, black traces; facilitated mode is an enhancement of open-channel probability over the basal level in the normal gating mode (10)]. When barium (Ba2+) was used as the charge carrier, channels opened directly into the normal gating mode and did not transition to the facilitated state, regardless of the prepulse potential (Fig. 1A, gray symbols). A measure of “pure” CDF was calculated by subtracting relative facilitation (RF) determined using Ca2+ as the charge carrier from RF when using Ba2+ (Fig. 1A, denoted as g) (9). The FHM-1 mutations, R192Q and S218L, represent distinct ends of the clinical spectrum, with patients possessing the R192Q alteration exhibiting a mild, pure FHM-1 without other neurological symptoms (6, 18), whereas patients with the S218L mutation have an associated severe clinical migraine phenotype most often associated with ataxia or other cerebellar symptoms (19–21). Fig. 1 shows that the R192Q (Fig. 1A, triangles) and S218L (Fig. 1A, diamonds) mutations both occlude Cav2.1 CDF across multiple prepulse potentials and pure CDF relative to WT channels (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

R192Q and S218L FHM-1 mutations inhibit Ca2+-dependent modulation of human recombinant Cav2.1 channels. (A) Using the paired-pulse protocol previously described (9), both the R192Q and S218L FHM-1 mutations are found to occlude CDF across several prepulse potentials shown as relative facilitation versus prepulse potential; results are means ± SEM. (B) Pure CDF (g) following a +20 mV prepulse is significantly reduced by the R192Q (g = 0.097 ± 0.042; *P < 0.05) and S218L (g = 0.023 ± 0.031; *P < 0.05) mutations compared with WT (g = 0.290 ± 0.046). (C) Using 1-s square test-pulses between −10 mV and +30 mV, the current remaining at 800 ms (r800) across several prepulse potentials is increased by both FHM-1 mutations relative to WT; data are means ± SEM. (D) Pure CDI (f) relative to WT (f = 0.418 ± 0.067) is modestly reduced by the R192Q mutation (f = 0.214 ± 0.082) but significantly reduced by the S218L mutation (f = 0.083 ± 0.038; *P < 0.05). (E) Paired-pulse protocol used and representative traces for peak CDF obtained following a +20 mV prepulse for WT, R192Q, and S218L Cav2.1 channels using Ca2+ (Top) and Ba2+ (Bottom) as charge carrier; traces normalized to the end of the test pulse. (F) Representative traces for CDI in which traces are normalized to the peak of a +10 mV test pulse. (G) APW used and representative traces for WT, R192Q, and S218L Cav2.1 channels. First hashed line represents the level of Ca2+ response during the first AP, and the second line represents the peak (maximum facilitation). The 100-Hz APW was derived from APs recorded in the calyx of Held (38, 54). n refers to the number of cells recorded. All statistics were obtained with use of one-way ANOVA.

The effect of FHM-1 mutations on CDI of exogenous Cav2.1 channels was tested using a 1-s test pulse to varying potentials in Ca2+ and Ba2+. WT Cav2.1 channels showed a typical CDI characterized by faster inactivation when Ca2+ was used as the charge carrier (Fig. 1C; black squares) relative to Ba2+ (Fig. 1C, gray, open squares; Fig. 1F, Left) (13, 17). A measure of pure CDI was determined by subtracting currents obtained using Ca2+ as the charge carrier from currents obtained using Ba2+ (Fig. 1C, denoted as f) (9). Although the R192Q mutation modestly reduced CDI relative to that of WT (Fig. 1C; triangles; Fig. 1F, Middle), the more severe S218L mutation (Fig. 1C, diamonds) significantly reduced the ability of channels to undergo CDI (Fig. 1D; Fig. 1F, Right). Importantly, because of its reliance on global Ca2+ levels (unlike that for CDF), CDI depends on Cav2.1 current density (22). Whereas the R192Q mutation has little effect on current density, the S218L mutation causes a large reduction in current density (23) (Fig. S2 shows similar findings). As such, at the mechanistic level, the reduced ability of mutant channels to undergo CDI is likely, at least in part, a result of reduced current density.

Although rectangular depolarizations allow for optimal biophysical resolution of CDF and CDI, it was also important to test the effects of FHM-1 mutations under conditions more resembling neuronal functioning such as AP waveforms (APWs) (13). In response to application of 100 Hz APW, WT channels displayed typical CDF and CDI that shaped the Ca2+ currents; CDF caused an initial facilitation of Ca2+ currents in the first few APs, and CDI caused a cumulative reduction as the APs continued to be applied (Fig. 1G) (9, 10). The FHM-1 R192Q and S218L mutations both strongly suppressed the dynamics of the response to APWs, consistent with their effects on CDF and CDI (Fig. 1G; Fig. S2 shows average Ca2+ responses and those using Ba2+ as the charge carrier).

As the biophysical effects of FHM-1 mutations can be affected by a number of factors, including Cav2.1 splice-variation (24), β subunit coexpression (25), and the nature of the expression system (7, 26), it was important to test the FHM-1 mutations in the context of native P/Q-type current modulation. In this regard, we measured P/Q-type currents in acutely dissociated cerebellar PCs from WT and R192Q and S218L knock-in mice (27–29).

FHM-1 Mutations Occlude CDF of Native P/Q-Type Currents in Cerebellar PCs.

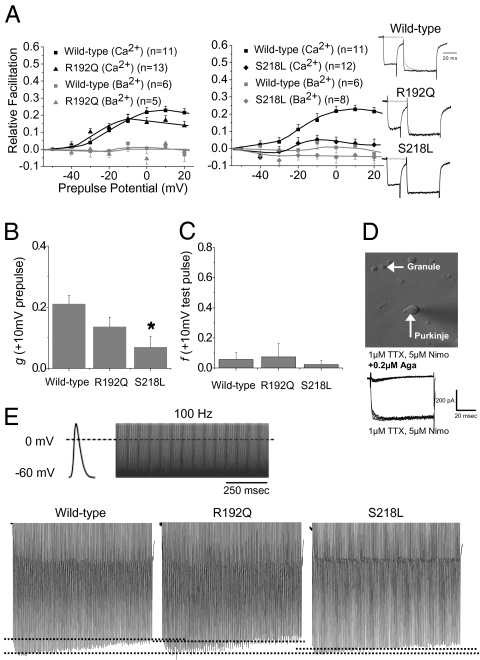

P/Q-type currents in acutely dissociated cerebellar PCs (approximately 90–95% of whole cell Ca2+ current; see refs 30, 31 and Fig. 2D) recapitulate the key features of CaM-mediated CDF observed in human recombinant Cav2.1 channels (17, 32, 33). In WT mice, P/Q-type currents in PCs showed similar CDF to that for WT human recombinant Cav2.1 channels (Fig. 2A). P/Q-type currents from dissociated PCs from homozygous R192Q and S218L knock-in mice had CDF reduced across both multiple prepulse potentials (Fig. 2A) and during APWs (Fig. 2E); however, only the more severe S218L mutation resulted in a statistically significant reduction in pure CDF (Fig. 2B). Fig. 2C shows that we did not detect significant CDI of endogenous P/Q-type currents in PCs from WT or R192Q and S218L mice. Of note, CDI of P/Q-type currents in dissociated PCs has been found to be variable under different recording conditions (17, 32, 33).

Fig. 2.

P/Q-type current CDF is altered in acutely dissociated PCs from FHM-1 R192Q and S218L knock-in mice. (A) Both the R192Q and S218L mutations occlude CDF across several prepulse potentials; results are means ± SEM (representative traces, far right). (B) Pure CDF (g) relative to WT (g = 0.210 ± 0.028) is not significantly reduced by R192Q (g = 0.136 ± 0.03), whereas the S218L mutation results in a significant reduction (g = 0.0686 ± 0.035; *P < 0.05). (C) There was no appreciable CDI of P/Q-type currents in PCs from WT (f = 0.058 ± 0.045) or R192Q (f = 0.074 ± 0.091) and S218L (f = 0.023 ± 0.028) mice. (D) P/Q-type currents were isolated from freshly dissociated cerebellar PCs identified by their characteristic large size and tear-shaped morphology. Exemplar trace below shows that the pharmacologically isolated P/Q-type currents were completely blocked with 0.2 μM ω-Aga-IVA. (E) APW used and representative traces for WT, R192Q, and S218L Cav2.1 channels. First hashed line represents the level of Ca2+ response during the first AP, and the second line represents the peak (maximum facilitation). n refers to the number of cells recorded. All statistics were obtained with use of a one-way ANOVA.

Taken together, the findings from the recombinant and endogenous P/Q-type channels support the notion that the FHM-1 R192Q and S218L mutations occlude CDF of P/Q-type channels. The effects on CDF suggest that FHM-1 mutations profoundly affect Ca2+-dependent regulation of P/Q-type channels and predicted the possibility of altering P/Q-type channel-dependent functions as they relate to synaptic signaling. Neither a contribution of CDF toward synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum or the demonstration whether FHM-1 mutations might affect fast synaptic cerebellar signaling has been reported. The PF–PC synapse is a well characterized (34), prototypical central synapse that relies predominantly on P/Q-type channels for neurotransmitter release and displays robust presynaptic forms of short-term facilitation via both paired-pulse and AP trains (35, 36). Although the specific modulators of facilitation at the presynaptic terminals of PFs have not been defined, we hypothesized that CDF of P/Q-type channels is an important means of short-term synaptic facilitation and further, that FHM-1 mutations affecting CDF would have a corresponding effect toward synaptic plasticity.

FHM-1 Mutations Attenuate Short-Term Synaptic Facilitation at the PF–PC Synapse.

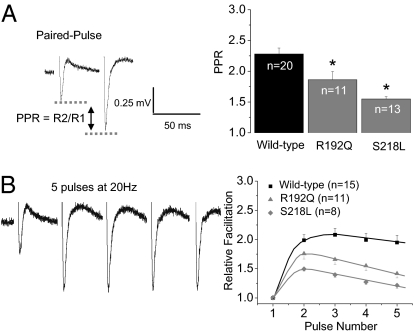

Synaptic transmission at the PF–PC synapse was measured by using extracellular field recordings in transverse slices from WT and homozygous R192Q and S218L knock-in mice. A typical facilitation response was evoked by paired, 20-Hz, 180-μs stimulations of PFs, in which the second excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) was facilitated relative to the first [i.e., paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) (36); Fig. 3A, Left]. Of note, the paired pulse ratio (PPR; size of the second pulse relative to the first) was significantly reduced by the R192Q and S218L mutations (Fig. 3A, bar graph), and in a manner quantitatively consistent with the reduction in Cav2.1 CDF in exogenous and native systems (compare with Figs. 1B and 2B). Following five 180-μs stimulations at 20 Hz, similar results were observed in that both the R192Q and S218L mutations significantly decreased the successive EPSPs relative to the first pulse (Fig. 3B). These results support the notion that CDF of Cav2.1 channels is a contributing and necessary component of synaptic plasticity in presynaptic terminals of PFs. However, an unresolved issue is whether FHM-1 mutant presynaptic channels are reluctant and/or unable to transition to a facilitated state resulting in decreased transmitter release, or whether they are in a constitutively facilitated state that basally increases presynaptic Ca2+ influx and transmitter release. Several lines of evidence led us to predict that the observed changes in synaptic plasticity at the PF–PC synapse results from a larger initial Ca2+ influx through basally facilitated mutant channels relative to unfacilitated WT channels in PF boutons (Fig. S3 and SI Discussion).

Fig. 3.

FHM-1 mutant mice exhibit attenuated PPF at the PF–PC synapse. (A, Left) Exemplar field recording of synaptic responses from the PCs evoked by two extracellular stimuli of approximately 15 V, 180 μs delivered at a 50-ms interval to PFs in the molecular layer (WT mouse). The PPR is a quantification of facilitation obtained by dividing response 2 (R2) by response 1 (R1). Right: PPR is significantly reduced relative to WT (2.36 ± 0.096) by both the R192Q (1.86 ± 0.13; *P < 0.05) and S218L mutations (1.60 ± 0.075; *P < 0.05); results are means ± SEM. (B) Left: Exemplar field recording of synaptic responses from the PCs evoked by five extracellular stimuli of approximately 15 V, 180 μs delivered at 20 Hz (WT mouse). (Right) RF was measured by dividing the peak response from each stimulus by the response obtained from the first stimulus, plotted versus pulse number; results are means ± SEM. Both mutations reduce RF during five pulses at 20 Hz. n refers to the number of slices recorded (from eight WT, four R192Q, and five S218L mice). All statistics were obtained with use of a one-way ANOVA.

FHM-1 Mutant P/Q-Type Channels Appear to Be in a Basally Facilitated State in PF Boutons.

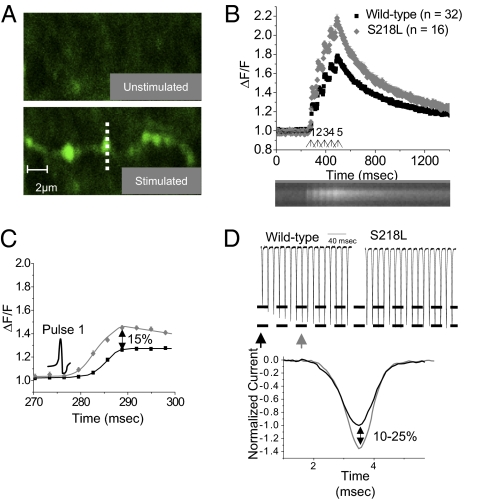

The geometry and spatial equilibration of Ca2+ in the PF boutons is ideal for measuring the role of Ca2+ dynamics on a tens-of-milliseconds time scale by using Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dyes (36, 37). To this end, we evoked a train of 5 PF responses (50-μs pulses at 20 Hz) in slices from WT or homozygous S218L mice and simultaneously monitored the fluorescent response of the Ca2+ indicator Rhod-2 in presynaptic boutons using two-photon microscopy in line-scan mode. We chose to examine the S218L mice because of the consistently larger effect on CDF. Fig. 4A shows an example of unstimulated (top) and stimulated (bottom) PFs in which the presynaptic boutons were detected as relatively bright regions. Ca2+ influx in boutons from S218L mice (Fig. 4B, gray diamonds) was enhanced during each of five PF responses compared with WT mice (Fig. 4B, black squares), suggesting channels containing the S218L mutation are in a basally facilitated state.

Fig. 4.

The kinetics of Ca2+ influx at PF terminals from S218L mice suggests a basal facilitation of P/Q-type channels. (A) PFs were stimulated with a silver wire electrode and two-photon imaging was used to measure Ca2+ transients in presynaptic terminals of the PFs; postsynaptic activity was blocked with 100 μM MCPG, 20 μM CNQX, and 50 μM APV. Line scans were used to measure individual terminals (representative terminal indicated by hashed line). Four sets of five 50-μs stimuli at 20 Hz were given and the Ca2+ transients were averaged for each terminal. (B) The average Ca2+ influx at PF terminals (normalized to the background fluorescence) is enhanced in S218L mice relative to WT littermates; results are means ± SEM (arrows represent the five stimuli). A representative average Ca2+ transient response measured for one terminal in line-scan mode is shown (Lower). (C) An expanded scale of B to show Ca2+ transient elicited during the first AP. Ca2+ transients in mutant terminals are larger in magnitude than WT terminals (peak enhanced approximately 15% relative to WT), as expected if mutant channels are in a basally facilitated gating mode. Stimulus is shown by AP illustration. n refers to the number of presynaptic terminals recorded (from five WT and five S218L mice). (D) Expanded view of CDF of recombinant channels during APW from Fig. 1G. Ca2+ currents through WT recombinant Cav2.1 channels increases as Ca2+ influx causes CDF (Left), whereas recombinant Cav2.1 channels containing the S218L mutation have a maximal Ca2+ response regardless of APs (Right). Bottom: Ca2+ currents through facilitated P/Q-type channels (gray trace) are larger than through unfacilitated channels (black trace) during evoked APs. A 10–25% increase in Ca2+ current amplitude was the range obtained from recombinant Cav2.1 channels in HEK cells (Fig. 1G) and endogenous P/Q-type currents in PCs (Fig. 2E). The unfacilitated trace is the Ca2+ response of a WT channel obtained during the first AP, and the facilitated trace is the Ca2+ response obtained during the 10th AP (indicated by arrows, Top, Left).

Assuming presynaptic Ca2+ currents through Cav2.1 channels can be modeled by Hodgkin–Huxley equations, a shift to more negative activation voltages by the FHM-1 mutations (24) theoretically could generate larger Ca2+ currents during APs (38); however, it was recently shown that, during short 1-ms APs elicited at the calyx of Held in R192Q mice, a hyperpolarizing shift in the activation voltage by the R192Q mutation was insufficient to alter presynaptic Ca2+ influx. Only when the AP duration was prolonged by 1 to 2 ms was the shift in the activation by the R192Q mutation sufficient to cause greater presynaptic Ca2+ influx (39). Importantly, the AP duration at PF terminals closely resembles the normal, 1-ms APs at the calyx of Held (40, 41), and therefore a shift to more negative activation voltages observed under square pulse depolarizations does not likely translate to an increase in Ca2+ influx by the S218L mutation during the normal, short APs at PF terminals. In contrast, Cav2.1 channels in the facilitated state have an enhanced Ca2+ influx during APs with durations of 1 ms or less (Figs. 1 and 2) (9, 10, 17, 42), and as such, channels rendered toward a facilitated state by the S218L mutation would be expected to show enhanced Ca2+ influx at PF terminals during evoked short APs. In further support, the amplitude of Ca2+ transients in the presynaptic boutons in S218L mice were enhanced by approximately 15% (Fig. 4C, pulse 1) which is consistent with the 10% to 25% enhancement of Ca2+ currents through facilitated P/Q-type channels relative to unfacilitated channels in recombinant and endogenous systems (Fig. 4D). The results appear to represent a true gain in P/Q-type channel function, as there was no apparent compensation by other Ca2+ channel subtypes at these boutons in the S218L mice (Fig. S4).

Discussion

It has been known for some time that there exist at least two mechanisms of facilitation at the PF–PC synapse: the well understood mechanism described by the residual Ca2+ hypothesis, and an incompletely resolved mechanism driven by a Ca2+ sensor with high Ca2+ affinity that can detect modest, transient levels of Ca2+, likely near the pore of presynaptic Ca2+ channels (37). The exact mechanisms and molecular players involved in the latter form of facilitation have not been reported, although a role for high-affinity CaSs such as CaM have been predicted (37, 43, 44). In this report we provide supporting evidence for the hypothesis that Ca2+ influx at PF boutons induces CDF of Cav2.1 channels as a means to enhanced Ca2+ influx during subsequent APs and achieve synaptic facilitation at this central synapse.

Our findings may also provide insight toward the molecular mechanisms of FHM-1 pathophysiology. We find that FHM-1 mutations likely render Cav2.1 channels in a basally facilitated state and that the facilitated channels result in a larger Ca2+ influx during APs in PF boutons relative to WT channels (Fig. 4). Of note, in previous experiments using single-channel recordings, some FHM-1 missense mutations (including R192Q and S218L) were shown to cause an overall gain-of-function Cav2.1 channel phenotype as a result of enhanced open-channel probability (7, 8). Likewise, the mechanism that underlies CDF of Cav2.1 channels has been determined to be a Ca2+/CaM-mediated transition of channels to a functional state with an enhanced open-channel probability and a facilitated mode of gating (10). As such, we predict that the basally facilitated state induced by the R192Q and S218L mutations reflects a state of enhanced open-channel probability that is the same as (or analogous to) the facilitated state resulting from CDF and that precludes any further CDF-mediated facilitation. In addition to affecting synaptic efficacy, we predict that this gain-of-function state represents an additional mechanism in migraine pathophysiology. To date there has not been an adequate explanation for the cerebellar ataxia associated with the FHM-1 phenotype. We hypothesize that disruption of Cav2.1 CDF and synaptic efficacy at the PF–PC synapse may explain the cerebellar ataxia often associated with FHM-1. PCs have regular intrinsic pacemaking that is shaped by various inhibitory and excitatory inputs onto PCs, and fine tuning (increase or decrease) of the interspike interval from that of intrinsic pacemaking conveys information to the deep cerebellar nuclei relevant to motor coordination (45). The significant increase in presynaptic Ca2+ influx and presumably enhancement in glutamate release from PF induced by the S218L FHM-1 mutation (Fig. 4) may alter the precise balance of excitatory and inhibitory inputs onto PC cells under certain conditions. As such, the fine tuning of PC firing may be compromised sufficiently to lead to cerebellar motor deficits including ataxia. In support, other mutations in the Cav2.1 subunit that increase, decrease, and/or alter the dynamics of excitatory inputs to PC have been correlated with aberrant motor phenotypes in other models involving episodic ataxia (46, 47).

The data presented in this report provide strong evidence that Cav2.1 CDF plays a critical role in synaptic plasticity at the PF-PC synapse. Considering that Cav2.1 channels are the predominant Ca2+ channel underlying synaptic transmission at most other fast synapses in the mammalian CNS (48), we predict Cav2.1 CDF is an unrecognized but significant contributor to short-term synaptic facilitation at other fast CNS synapses.

Materials and Methods

SI Materials and Methods provides details of solutions and procedures. In brief, HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with WT, R192Q, or S218L human Cav2.1 in combination with β2, α2δ, and CD8 as previously described (24). Cerebellar PCs from WT or homozygous R192Q and S218L mice between postnatal days 15 to 25 were enzymatically isolated using similar dissociation techniques previously described (49–51). In both cases, macroscopic Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique (52). CDF was analyzed using a two-pulse protocol in which 50-ms test pulses to +5 mV (−10 mV in PCs) were given subsequent to no prepulse or prepulses ranging from −90 mV to +100 mV (or −50 to +40 mV in PCs), or during APWs (9). CDI was measured using a square pulse protocol including a 1-s test depolarization (500 ms in PCs) ranging from −10 mV to +30 mV, in 10-mV increments, from a holding of −90 mV (−60 mV holding in PCs). For extracellular field recording and two-photon imaging experiments, cerebellar vermi were cut into 300-μm transverse slices and maintained for 1 to 6 h at room temperature in artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF). For two-photon imaging experiments, neurons in cerebellar slices were bulk-loaded with Rhod-2 AM using a modified Cremophor-loading technique adapted from Trevelyan et al. (53). PFs were stimulated with a silver wire electrode and presynaptic imaging performed with a two-photon laser scanning microscope directly coupled to a 10 W Chameleon ultrafast laser (Coherent).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bruce Bean, Amy Lee, and David Yue for protocols and advice on optimizing PC dissociation procedures; Dr. David Parker, Luke Materek, and Paul Lam for providing human Cav2.1 α1 subunit constructs (University of British Columbia, Vancouver); Drs. Patrick Francis and Charles A. Haynes for generating CDF analysis software; and Dr. Simon Kaja for initial setup and care of the FHM-1 mice colony. The work was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (T.P.S and B.A.M), Canada Research Chair Awards (to T.P.S and B.A.M), University Graduate Fellowship and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Awards (to P.J.A), and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Studentship Award (to R.L.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1009500107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T. Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;512:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.723bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujimoto T, Jeromin A, Saitoh N, Roder JC, Takahashi T. Neuronal calcium sensor 1 and activity-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type calcium currents at presynaptic nerve terminals. Science. 2002;295:2276–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.1068278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochida S, Few AP, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Regulation of presynaptic Ca(V)2.1 channels by Ca2+ sensor proteins mediates short-term synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;57:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ophoff RA, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell. 1996;87:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hans M, et al. Functional consequences of mutations in the human alpha1A calcium channel subunit linked to familial hemiplegic migraine. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1610–1619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tottene A, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations increase Ca(2+) influx through single human CaV2.1 channels and decrease maximal CaV2.1 current density in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13284–13289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192242399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri D, et al. Alternative splicing as a molecular switch for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6334–6342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhuri D, Issa JB, Yue DT. Elementary mechanisms producing facilitation of Cav2.1 (P/Q-type) channels. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:385–401. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee A, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation and inactivation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin binds to and modulates P/Q-type calcium channels. Nature. 1999;399:155–159. doi: 10.1038/20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS, Yue DT. Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2001;411:484–489. doi: 10.1038/35078091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A, et al. Differential modulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein 1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:210–217. doi: 10.1038/nn805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Few AP, Lautermilch NJ, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Differential regulation of CaV2.1 channels by calcium-binding protein 1 and visinin-like protein-2 requires N-terminal myristoylation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7071–7080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0452-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A, Zhou H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent regulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:16059–16064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8282–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ducros A, et al. The clinical spectrum of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with mutations in a neuronal calcium channel. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:17–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzsimons RB, Wolfenden WH. Migraine coma. Meningitic migraine with cerebral oedema associated with a new form of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia. Brain. 1985;108:555–577. doi: 10.1093/brain/108.3.555-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kors EE, et al. Delayed cerebral edema and fatal coma after minor head trauma: Role of the CACNA1A calcium channel subunit gene and relationship with familial hemiplegic migraine. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:753–760. doi: 10.1002/ana.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan YC, et al. Electroencephalographic changes and seizures in familial hemiplegic migraine patients with the CACNA1A gene S218L mutation. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:891–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soong TW, et al. Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel alpha1(2.1) subunits: Implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10142–10152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tottene A, et al. Specific kinetic alterations of human CaV2.1 calcium channels produced by mutation S218L causing familial hemiplegic migraine and delayed cerebral edema and coma after minor head trauma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17678–17686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PJ, et al. Ca(V)2.1 P/Q-type calcium channel alternative splicing affects the functional impact of familial hemiplegic migraine mutations: Implications for calcium channelopathies. Channels (Austin, Tex) 2009;3:110–121. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.2.7932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müllner C, Broos LA, van den Maagdenberg AM, Striessnig J. Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutations K1336E, W1684R, and V1696I alter Cav2.1 Ca2+ channel gating: Evidence for beta-subunit isoform-specific effects. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51844–51850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus RL, Sinnegger MJ, Glossmann H, Hering S, Striessnig J. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations change alpha1A Ca2+ channel kinetics. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5586–5590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Maagdenberg AM, et al. A Cacna1a knockin migraine mouse model with increased susceptibility to cortical spreading depression. Neuron. 2004;41:701–710. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eikermann-Haerter K, et al. Androgenic suppression of spreading depression in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant mice. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:564–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.21779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tottene A, et al. Enhanced excitatory transmission at cortical synapses as the basis for facilitated spreading depression in Ca(v)2.1 knockin migraine mice. Neuron. 2009;61:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintz IM, et al. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin omega-Aga-IVA. Nature. 1992;355:827–829. doi: 10.1038/355827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreiner L, Christel CJ, Benveniste M, Schwaller B, Lee A. Compensatory regulation of Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons lacking parvalbumin and calbindin D-28k. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:371–381. doi: 10.1152/jn.00635.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benton MD, Raman IM. Stabilization of Ca current in Purkinje neurons during high-frequency firing by a balance of Ca-dependent facilitation and inactivation. Channels (Austin, Tex) 2009;3(6) doi: 10.4161/chan.3.6.9838. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voogd J, Glickstein M. The anatomy of the cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atluri PP, Regehr WG. Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5661–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borst JG, Sakmann B. Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;513:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.149by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inchauspe C, et al. Gain of function in Fhm-1 Cav2.1 knock-in mice is related to the shape of the action potential. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:291–299. doi: 10.1152/jn.00034.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Control of neurotransmitter release by presynaptic waveform at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3425–3435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Timing of neurotransmission at fast synapses in the mammalian brain. Nature. 1996;384:170–172. doi: 10.1038/384170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreiner L, Christel CJ, Benveniste M, Schwaller B, Lee A. Compensatory regulation of Cav2.1 Ca2+ channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons lacking parvalbumin and calbindin D-28k. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:371–381. doi: 10.1152/jn.00635.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ullrich B, et al. Functional properties of multiple synaptotagmins in brain. Neuron. 1994;13:1281–1291. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, et al. Ca(2+)-dependent and -independent activities of neural and non-neural synaptotagmins. Nature. 1995;375:594–599. doi: 10.1038/375594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebner TJ. A role for the cerebellum in the control of limb movement velocity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:762–769. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsushita K, et al. Bidirectional alterations in cerebellar synaptic transmission of tottering and rolling Ca2+ channel mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4388–4398. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04388.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou YD, Turner TJ, Dunlap K. Enhanced G protein-dependent modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the cerebellum of the Ca2+ channel-mutant mouse, tottering. J Physiol. 2003;547:497–507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westenbroek RE, et al. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the alpha 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6403–6418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06403.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raman IM, Sprunger LK, Meisler MH, Bean BP. Altered subthreshold sodium currents and disrupted firing patterns in Purkinje neurons of Scn8a mutant mice. Neuron. 1997;19:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80969-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swensen AM, Bean BP. Ionic mechanisms of burst firing in dissociated Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9650–9663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swensen AM, Bean BP. Robustness of burst firing in dissociated purkinje neurons with acute or long-term reductions in sodium conductance. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3509–3520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3929-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trevelyan AJ, Sussillo D, Watson BO, Yuste R. Modular propagation of epileptiform activity: Evidence for an inhibitory veto in neocortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12447–12455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2787-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patil PG, Brody DL, Yue DT. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20:1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.