Abstract

BK-type K+ channels are activated by voltage and intracellular Ca2+, which is important in modulating muscle contraction, neural transmission, and circadian pacemaker output. Previous studies suggest that the cytosolic domain of BK channels contains two different Ca2+ binding sites, but the molecular composition of one of the sites is not completely known. Here we report, by systematic mutagenesis studies, the identification of E535 as part of this Ca2+ binding site. This site is specific for binding to Ca2+ but not Cd2+. Experimental results and molecular modeling based on the X-ray crystallographic structures of the BK channel cytosolic domain suggest that the binding of Ca2+ by the side chains of E535 and the previously identified D367 changes the conformation around the binding site and turns the side chain of M513 into a hydrophobic core, providing a basis to understand how Ca2+ binding at this site opens the activation gate of the channel that is remotely located in the membrane.

Keywords: Ca2+-activated, allosteric gating, Ca2+ binding site, Cd2+, Slo1

Large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels open in response to membrane depolarization and the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). In neurons and muscle cells, membrane depolarization activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, resulting in Ca2+ entry into the cell and subsequent activation of BK channels. The K+ efflux through BK channels repolarizes the membrane, which shuts Ca2+ channels, thereby providing a negative feedback mechanism to modulate membrane excitability and [Ca2+]i. Because of this function, BK channels are important modulators of muscle contraction (1), neuronal spike frequency adaptation (2), neurotransmitter release (3), and circadian pacemaker output (4). BK channels are formed by four Slo1 subunits (5, 6). Each Slo1 contains a membrane-spanning domain, which comprises the pore-gate domain (PGD) and the voltage sensing domain (VSD), and a cytosolic domain (CTD) (7, 8), which is made of two regulating domains for K+ conductance (RCK1 and RCK2) (9, 10). Intracellular Ca2+ binds to the CTD to activate the channel by enhancing the open probability of the activation gate located in the membrane-spanning PGD.

Previous studies have identified two putative Ca2+ binding sites in the CTD of BK channels, one is the Ca2+ bowl located in the RCK2 domain (10 –13) and the other is located in the RCK1 domain including the residue D367 (14). The existence of two distinctively different high-affinity Ca2+ binding sites that are responsible for Ca2+-dependent activation of BK channels has been demonstrated in various experimental studies (15). These studies demonstrated that Ca2+ binding to the two sites activates channel independently with only a small cooperativity (14, 16, 17), and the two sites show differences in various properties including affinities for Ca2+ (14, 17), voltage dependence (17), and the molecular mechanisms of coupling to the activation gate (18). The distinction between the properties of the two putative Ca2+ binding sites may lead to different physiological roles of these sites. For instance, a mutation in Slo1 that is associated with epilepsy and dyskinesia in human (19) specifically enhances the coupling of the RCK1 site to the activation gate to increase Ca2+ sensitivity of channel activation (18).

Although previous studies showed that the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1 is important for physiological functions, its molecular identity is less certain than that of the Ca2+ bowl. In the Ca2+ bowl, previous mutagenesis studies (13) and a recently published X-ray crystallographic structure of the Ca2+-bound Slo1 CTD demonstrate that a Ca2+ ion is coordinated by the side chains of D898 and D900 and the main chain carbonyls from Q892 and D895 (10). On the other hand, besides D367, no other residues have been identified to be part of the putative RCK1 Ca2+ binding site. Surprisingly, the same structure of CTD in high Ca2+ concentration did not identify any second Ca2+ binding site although the residue D367 is shown (10). To gain a better understanding of how the RCK1 Ca2+ binding site contributes to physiological functions and to solve the discrepancy between the structural data and the results from functional studies, further studies of this binding site are needed.

During the last 2 y, we have searched residues other than D367 that may be part of the putative Ca2+ binding site in RCK1 by systematic mutagenesis. These experiments show that the mutations of E535 in the RCK1 domain produce nearly identical functional consequences on the Ca2+-dependent activation as the mutations of D367. Therefore, both E535 and D367 may be part of the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1. We found that mutations of M513, some of which have been shown to reduce Ca2+ sensitivity (20), result in a different pattern of functional consequences than those of E535 and D367, which suggests that M513 may not be part of the Ca2+ binding site. We have also investigated Cd2+-dependent activation of BK channels and found that Ca2+ and Cd2+ interact with different sets of residues to activate BK channels, but some of the residues important for Cd2+-dependent activation may overlap with part of the putative Ca2+ binding site in RCK1. These results identify a cluster of residues that are important for BK channel function and further differentiate their roles in controlling channel gating. The Ca2+ binding site formed by D367 and E535 is consistent with the recently solved structures of BK channel CTD (9, 10) and provides a basis for understanding how the Ca2+ binding site couples to the activation gate during Ca2+-dependent activation.

Results and Discussion

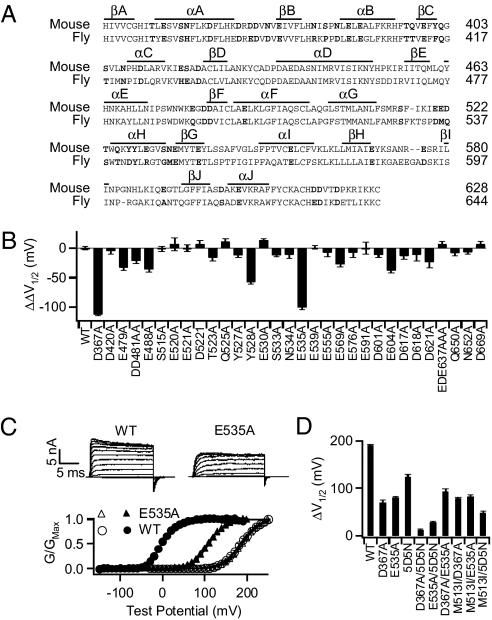

Ca2+ ions bound to proteins are usually coordinated by oxygen-containing side chains, main chain carbonyl groups, and water molecules (21). To search for an oxygen-containing residue that may be part of the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1, we mutated most Asp, Glu, Asn, Gln, Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues in RCK1 to Ala individually (Fig. 1A), which are possibly located close to D367 in structural models of RCK1 based on the structure of the RCK domain of MthK (22). We examined the change in Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel due to these mutations, and Fig. 1B shows the results of the mutations in the C-terminal half of RCK1. The results of the mutations in the N-terminal AC region have been shown (18). In response to increases in [Ca2+]i, the conductance-voltage (G-V) relation of BK channels shifts to more negative voltage ranges (23) (Fig. 1C). Because the effect of voltage on Ca2+-dependent activation is weak (17, 24, 25), this property has been used as an effective measure of Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channels in most studies of BK channel function (26). Similarly, here we define Ca2+ sensitivity as the G-V shift in response to the [Ca2+]i change from 0 to the saturating 100 μM, ΔV 1/2 = V 1/2 at 0 [Ca2+]i – V 1/2 at 100 μM [Ca2+]i, V 1/2 is the voltage where G-V is half maximum. Mutations alter Ca2+ sensitivity and the change in Ca2+ sensitivity, ΔΔV 1/2 = ΔV 1/2 mut – ΔV 1/2 wt for all of the Ala scan mutations described above is shown (Fig. 1B). Similar to reported (14), D367A reduces more than half of the total Ca2+ sensitivity, with ΔΔV 1/2 = −112.8 ± 2.3 mV (Fig. 1B). Of all other mutations, E535A reduces Ca2+ sensitivity similarly as D367A (Fig. 1B) (18), suggesting that E535 may play an equivalent role as D367 in Ca2+ binding.

Fig. 1.

The E535A mutation reduces Ca2+ sensitivity of mSlo1 BK channel activation. (A) Sequence alignment of the RCK1 domain of mouse (GenBank accession number, GI: 347143) and fly (Drosophila, GI: 7301192) Slo1. The residues in bold from the mSlo1 were mutated to Ala as shown in B and ref. 18. Lines above the sequence indicate secondary structures. The numbers at right indicate the sequence number of the last amino acid. (B) Effect of mutations on Ca2+ sensitivity. ΔV 1/2 and ΔΔV 1/2 are defined in the text. D367A and E535A result in the largest reductions in Ca2+ sensitivity. (C) Macroscopic current traces from inside-out patches expressing WT and E535A mutant channels. Currents were elicited in 100 μM [Ca2+]i by voltage pulses from −150 to 190 mV at 20-mV increment. The voltages before and after the pulses were −50 and −80 mV, respectively. G-V curves for WT and E535A mutation channels in [Ca2+]i of nominal 0 (≈0.5 nM, open symbols) and 100 μM (filled symbols). The solid lines are fittings of the Boltzmann relation. (D) Effect of individual and combined mutations on Ca2+ activation. Error bars in this and other figures show the SE of mean (n = 6–15).

The E535A mutant channel retains part of Ca2+ sensitivity; the G-V relation of the channels shifts to negative voltages in response to an increase of [Ca2+]i from 0 to 100 μM (Fig. 1 C and D). An additional mutation 5D5N, which substitutes the five consecutive Asp residues in the Ca2+ bowl with Asn, nearly eliminates the remaining Ca2+ sensitivity of E535A (Fig. 1D), indicating that E535A reduces Ca2+ sensitivity specifically derived from the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1. Consistent with this result, a double mutation D367A/E535A reduces Ca2+ sensitivity similarly as either D367A or E535A (Fig. 1D), indicating that E535A, similar to D367A, destroys Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site.

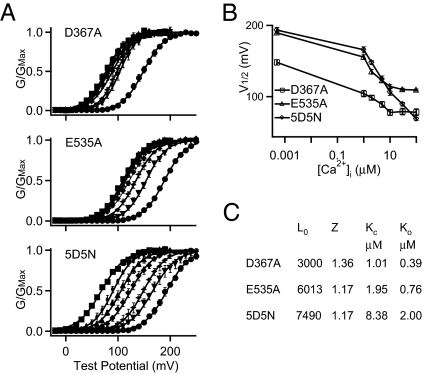

Previous studies measured Ca2+-dependent activation derived from either the RCK1 site or the Ca2+ bowl by mutating the other site and found that the two sites show different affinities for Ca2+ (14, 17). To further examine whether E535A destroys Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site, we measured G-V relations of the mutant channel at various [Ca2+]i from 0 to 100 μM (Fig. 2A). Comparing the pattern of G-V shifts at various [Ca2+]i among mutants D367A, E535A, and 5D5N, it is apparent that the E535A channels behave more similarly as D367A than 5D5N, with a larger reduction of Ca2+ sensitivity and less even distribution of G-V relations along the voltage axis (Fig. 2 A and B). Fitting the G-V relations of each mutant channel with a voltage-dependent Monod–Wyman–Changeux (MWC) model (27), we obtained apparent affinity of Ca2+ binding sites (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that 5D5N destroys the Ca2+ bowl that has a higher affinity for Ca2+, leaving the RCK1 site intact with a lower affinity for Ca2+. However, both E535A and D367A destroy Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site that has a lower Ca2+ affinity.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+ dependence of the E535A mutant channels is similar to that of D367A. (A) Normalized G-V relations of the D367A, E535A, and 5D5N mutant channels in [Ca2+]i from nominal 0 (≈0.5 nM) (•), 1 μM (▼), 2 μM ( ), 5 μM (◆), 10 μM (▲), 30 μM (◆), and 100 μM (■). The solid lines are fittings with the MWC model. (B) V

1/2 versus [Ca2+]i for the D367A, E535A, and 5D5N mutant channels, showing a similar steepness between E535A and D367A. (C) Parameters of the MWC model from fitting the G-V relations of D367A, E535A, and 5D5N.

), 5 μM (◆), 10 μM (▲), 30 μM (◆), and 100 μM (■). The solid lines are fittings with the MWC model. (B) V

1/2 versus [Ca2+]i for the D367A, E535A, and 5D5N mutant channels, showing a similar steepness between E535A and D367A. (C) Parameters of the MWC model from fitting the G-V relations of D367A, E535A, and 5D5N.

Fig. 2 also shows that E535A and D367A affect BK channel gating with different details. First, in 0 [Ca2+]i, the G-V relation of D367A is shifted to less-positive voltage ranges compared with that of the WT mSlo1 or E535A (Fig. 2 A and B). Second, in the intermediate [Ca2+]i, the G-V relations of D367A show a steeper slope, which makes these G-V curves appear more shifted away from that in 0 [Ca2+]i as compared with those of E535A (Fig. 2A). All these differences between the two mutant channels suggest that, in addition to affecting Ca2+-dependent activation, D367A also alters voltage-dependent activation of BK channels. This result is consistent with the location of D367 that is close to the VSD of the channel in the membrane (9, 10). Previous results have demonstrated that the cytosolic domain interacts with the VSD during BK channel activation (28, 29), and such interactions may result in a weak voltage dependence of Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site (17). Thus, it is possible that the mutation D367A also alters function of the VSD, resulting in changes of voltage-dependent activation.

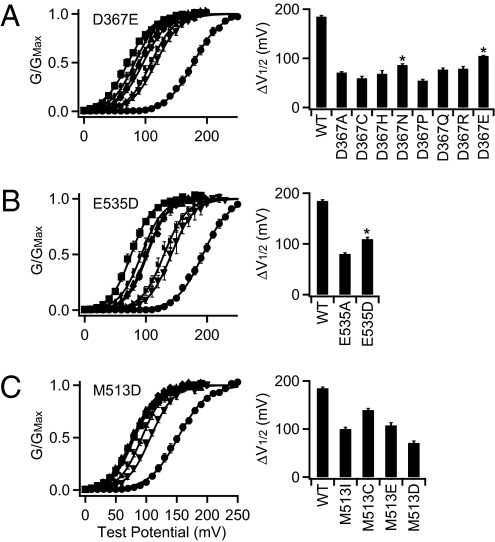

Because in a systematic Ala scan of oxygen-containing residues only the mutations of D367 and E535 nearly eliminate Ca2+ sensitivity in addition to the Ca2+ bowl mutation 5D5N (Fig. 1), D367 and E535 are likely to be part of the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1 of BK channels where the side chain of the acidic residues may coordinate Ca2+. To further examine whether these residues have the properties of a Ca2+ coordinator, we measured Ca2+ sensitivity of the mutations of D367 to various amino acids and found that D367E retains a Ca2+ sensitivity that is significantly greater than that retained by D367A (Fig. 3A; see Fig. S1A for current traces). This result is consistent with the idea that the oxygen atoms from the side-chain carboxylate groups of D367 or E367 can coordinate Ca2+, but because of the difference in the size of side chains, D367E may alter the structure of the binding site and, thus, impair Ca2+ sensitivity. Likewise, E535D also retains more Ca2+ sensitivity than E535A (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1B), indicating that E535 has similar properties of a Ca2+ coordinator.

Fig. 3.

Properties of E535 and D367 but not M513 are consistent with calcium binding coordinators. Left are G–V relations of D367E (A), E535D (B), and M513D (C) in [Ca2+]i from nominal 0 (≈0.5 nM) (•), 1 μM (▼), 2 μM ( ), 5 μM (◆), 10 μM (▲), 30 μM (◆), and 100 μM (■), fitted with the Boltzmann relation (filled lines), and Right are Ca2+ sensitivity of D367 (A), E535 (B), and M513 (C) mutated to various amino acids. ΔV

1/2 is defined in the text. *, Ca2+ sensitivity of the mutated channel is significantly larger than that of the mutation to Ala (P < 0.005).

), 5 μM (◆), 10 μM (▲), 30 μM (◆), and 100 μM (■), fitted with the Boltzmann relation (filled lines), and Right are Ca2+ sensitivity of D367 (A), E535 (B), and M513 (C) mutated to various amino acids. ΔV

1/2 is defined in the text. *, Ca2+ sensitivity of the mutated channel is significantly larger than that of the mutation to Ala (P < 0.005).

A previous study showed that the mutation M513I in the RCK1 domain reduces Ca2+ sensitivity (20) (Fig. 3C and Fig. S1C). The double mutation M513I/D367A does not cause any reduction of Ca2+ sensitivity in addition to D367A, but M513I/5D5N reduces Ca2+ sensitivity more than 5D5N alone (Fig. 1D), indicating that M535I affects the Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site. Likewise, M513I/E535A does not cause any reduction of Ca2+ sensitivity in addition to E535A (Fig. 1D), further supporting that E535 is part of the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1. Ca2+ prefers to bind to hard oxygen-containing ligands; the soft sulfur in the side chain of Met residues usually is not found to coordinate Ca2+ in other Ca2+ binding proteins (21, 30). If M513 coordinates Ca2+ in BK channels, a change of M513 to an oxygen-containing residue is expected to retain or even enhance Ca2+ sensitivity. We mutated M513 to Ile, Cys, Asp, and Glu residues and found that M513D reduces Ca2+ sensitivity more than any other mutations, whereas M513C reduces Ca2+ sensitivity the least (Fig. 3C). These results are in contrast to the profile of mutational results on D367 or E535, indicating that M513 does not have the properties of a Ca2+ coordinator. Therefore, the mutations of M513 may reduce Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channel by altering the structure of the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1 (see below).

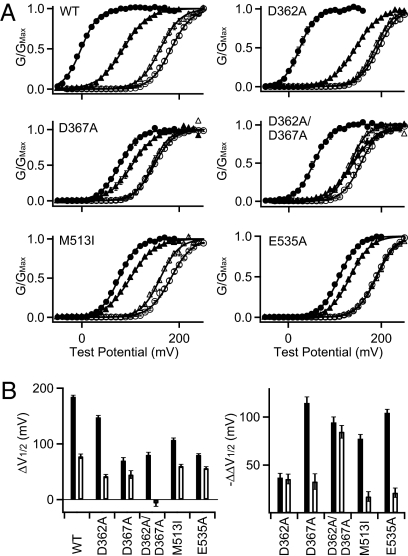

Besides Ca2+, other divalent cations, including Cd2+, also activate BK channels (31). Previous studies suggested that Cd2+ might interact with the Ca2+ binding site in RCK1 but not the Ca2+ bowl because the double mutation D362A/D367A nearly abolished Cd2+ sensitivity (32) (Fig. 4; see Fig. S2 for current traces), whereas mutations of the Ca2+ bowl had no effect on Cd2+ sensitivity (11, 32). To examine whether the same residues are important for both Ca2+- and Cd2+-dependent activation, we examined the effect of mutations D362A, D367A, M513I, and E535A on Cd2+-dependent activation. The results show that the effect of these mutations on Cd2+ sensitivity is not correlated with the effect on Ca2+-dependent activation (Fig. 4 A and B). First, none of the individual mutations abolishes Cd2+ sensitivity, although D367A and E535A nearly abolish the Ca2+ sensitivity derived from the RCK1 site (Fig. 1). Second, D362A reduces Ca2+ sensitivity by the smallest fraction among all individual mutations but reduces Cd2+ sensitivity by the largest fraction. On the other hand, M513I and E535A have large effects on Ca2+ sensitivity but small effects on Cd2+ sensitivity. Thus, only D367 is important for both Ca2+- and Cd2+-dependent activations, whereas other residues are important for either Ca2+- or Cd2+-dependent activation. Therefore, Cd2+ does not seem to bind to the same site as Ca2+. Additionally, because D362A and D367A both reduce approximately half of Cd2+ sensitivity (ΔV 1/2 mut − ΔV 1/2 wt = −35.5 ± 5.1 mV and −32.8 ± 8.1 mV, respectively; Fig. 4B) and the effects of the two individual mutations add up to that of the double mutation D362A/D367A (ΔV 1/2 mut − ΔV 1/2 wt = −84.6 ± 6.6 mV), D362 and D367 seem to affect Cd2+ sensitivity independently and neither seem to be necessary for Cd2+ binding.

Fig. 4.

The effects of mutations on Cd2+ sensitivity are not correlated with that on Ca2+ sensitivity. (A) G-V relations in 0 (open circles) and 100 μM (filled circles) [Ca2+]i, and 0 (open triangles) and 100 (filled triangles) [Cd2+]i, fitted with the Boltzmann relation (filled lines). (B) Effects of Ca2+ (filled bars) and Cd2+ (open bars) on the WT and mutant channels. (Left) ΔV 1/2 = V 1/2 at 0 [Ca2+]i (or [Cd2+]i) − V 1/2 at 100 μM [Ca2+]i (or [Cd2+]i). (Right) ΔΔV 1/2 = ΔV 1/2 of mutations − ΔV 1/2 of WT.

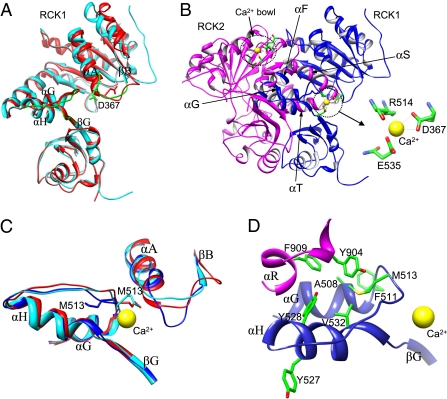

Recently, two crystal structures of the gating ring from the human BK channel were experimentally determined, representing two different conformations of the gating ring: One is the Ca2+-bound conformation crystallized in the presence of 50 mM [Ca2+]i (PDB ID code: 3MT5) (10), and the other is the Ca2+-free structure (PDB ID code: 3NAF) (9) (Fig. 5A). However, interestingly, only one Ca2+ is present at the Ca2+ bowl in the RCK2 domain of the Ca2+-bound crystal structure, whereas no Ca2+ is observed at the putative D367/E535 site. Based on the Ca2+-free structure, it was predicted that D367 and E535 could form a Ca2+ binding site (9). However, the structure is in the Ca2+-free conformation, and the side chains of D367 and E535 in the structure are not close enough to coordinate a Ca2+ ion. Comparisons between the RCK1 domains of the Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free structures show that, although the overall architectures of the two conformations are similar, the conformations differ significantly around the D367/E535 binding site. This flexible region includes three segments: the loop between αA and βB, the loop between αG and αH, and the linker between αH and βG (Fig. 5A). The conformational changes suggest flexibility around the D367/E535 binding site, which binds and releases Ca2+ during the functional cycle of the BK channel. In other words, in addition to the two conformations shown by the crystal structures, there should be a third conformation of RCK1 that allows binding of Ca2+ at the D367/E535 site. Here, we model the conformation of RCK1 bound with Ca2+ near D367/E535 based on the Ca2+-free crystal structure (9), in which the side chain of the critical residue D367 points outward to the solvent and, thus, better resemble the Ca2+-bound conformation because Ca2+ ions stay in the solvent before binding.

Fig. 5.

Molecular modeling for the mechanism of Ca2+-dependent activation of BK channels. (A) Comparison of the RCK1 domains between the Ca2+-bound crystal structure (PDB ID code: 3MT5, red) and Ca2+-free crystal structure (PDB ID code: 3NAF, cyan). Three flexible segments (green) show significant conformational discrepancy around the residue D367 (in stick mode). (B) Two Ca2+ ions (yellow spheres) bound on the modeled RCK1 (blue) and RCK2 (magenta) domains of the BK channel. The Ca2+ on RCK1 is coordinated by residues D367, R514, and E535 (Inset). (C) Comparison of the Ca2+ binding sites in RCK1 between the model (blue) and two crystal structures (PDB ID codes: red: 3MT5; cyan: 3NAF), in which the important residue M513 is shown in stick mode. (D) Details of the hydrophobic core around M513. The bound Ca2+ ion is shown for reference. Note: Y527 does not belong to the hydrophobic core.

Fig. 5B shows two Ca2+ ions binding to the modeled RCK1-RCK2 structure of the BK channel. It can be seen that the Ca2+ ion that binds at the D367/E535 site is coordinated by one main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of R514 and four oxygen atoms from the side-chain carboxylate groups of D367 and E535, which is consistent with the previous study (14) and our experimental results (Figs. 1–3) (also see SI Results and Discussion and Fig. S3). Because only the main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of R514 coordinates the binding of the Ca2+ ion, it is expected that mutants of this residue would not have much effect on atomic coordination for Ca2+ and, therefore, the Ca2+ sensitivity of the BK channel.

Comparisons between our modeled RCK1 conformation and the two crystal structures (9, 10) show that our RCK1 model experiences larger conformational changes around the D367/E535 binding site and better coordinates the Ca2+ ion (Fig. 5C). In addition to the directly interacting residues D367, R514, and E535 of Ca2+, another notable residue involved in the conformational change is M513. In the crystal structures, the side chain of M513 points toward the Ca2+ binding pocket. However, in our modeled structure, the side chain of M513 adopts a completely different orientation and points toward the protein due to the conformational change induced by Ca2+ binding in the loop where D367 locates (Fig. 5C). Further examinations on the surrounding environment of M513 in our model reveal that M513 would contribute to Ca2+ binding in the following way: The hydrophobic side chain of M513 points toward the interface between RCK1 and RCK2, forming a hydrophobic cluster core with the residues A508, F511, Y528, and V532 from RCK1 and residues Y904 and F909 from RCK2 (Fig. 5D). This hydrophobic core would be critically important for stabilizing the interface between RCK1 and RCK2 and the subdomain from αG to βG that contains the coordinating residues R514 and E535 of Ca2+. In other words, to allow binding of Ca2+, it would be necessary for the side chain of M513 to face the hydrophobic core at the interface between RCK1 and RCK2 so as to maintain the local structural integrity of the Ca2+ binding site, as shown in our modeled dimeric structure (Fig. 5D). Although both Met and Ile are hydrophobic residues, the side chain of Ile is shorter and bulkier than that of Met, which may affect the crowded hydrophobic core that contains multiple aromatic residues. On the other hand, the hydrophobic Cys residue better resembles Met despite its shorter length than Met. Therefore, the Ca2+ binding site would be affected more by charged mutations M513D, M513E, and M513I than M513C (Fig. 3). Fig. 1B shows that Y528, one of the critical residues in the above hydrophobic core (Fig. 5D), is also important to Ca2+ binding because Y528A significantly reduces Ca2+ sensitivity of the BK channel. In contrast, the neighboring residue Y527, which points to the solvent and is not part of the hydrophobic core (Fig. 5D), has little effect on the Ca2+ sensitivity when it is mutated to Ala (Fig. 1B).

Previous studies indicated that E374 and E399 in the cytosolic RCK1 form a Mg2+ binding site with D99 and N172 in the membrane-spanning VSD in BK channels (29). The Mg2+ ion bound to the interface between the VSD and RCK1 activates the BK channel by an electrostatic repulsion to the S4 segment (28). These results suggest that RCK1 is located close to the VSD and the two domains interact intimately, which is corroborated by an electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM) structure of BK channels (33). D367 is situated in a loop between αA and βB in RCK1 (Fig. 5A) that is located close to the membrane. It is possible that the conformation of the D367/E535 Ca2+ binding site is affected by the membrane-spanning domain of the BK channel. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that mutations in the intracellular loop between the transmembrane segment S0 and S1 alter Ca2+ sensitivity of channel activation (34). Because the Ca2+-bound crystal structure of the BK channel CTD was solved in the absence of the membrane-spanning domain (10), it is possible that the absence of a Ca2+ at the D367/E535 site and the misorientation of M513 side chain are due to the lack of the influence of the membrane-spanning domain on the conformation of the site.

Our recent study indicated that the N-terminal half of RCK1 from βA to αC (the AC region; Fig. 1A) is important in mediating Ca2+ binding to the site in RCK1 to the opening of the activation gate located in the membrane-spanning domain (18). Such an allosteric coupling is also affected by changes in intracellular viscosity, suggesting that molecular dynamics of the CTD are important in the coupling to activate the BK channel (18). This mechanism is consistent with the formation of the Ca2+ binding site by D367 and E535, which come from the AC region and the peripheral domain in RCK1, respectively, and bridge across the flexible interface between RCK1 and RCK2 that is formed by αF and αG from RCK1 and αS and αT from RCK2 (10) (Fig. 5B). Thus, the binding of Ca2+ to this site may pull and stabilize the AC region and turn the M513 side chain into the hydrophobic core formed at one side of the flexible interface, which may affect the AC region at the other side of the flexible interface (Fig. 5 B and D), thereby opening the channel via the AC region.

Materials and Methods

All mutations were generated from the mbr5 splice variant of mouse Slo1 (mSlo1) (8) by using overlap-extension PCR (35) and verified by sequencing. Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with 0.05–20 ng of cRNA/oocyte, and currents were recorded in 2–4 d.

Macroscopic currents were recorded from inside-out patches. The data acquisition and analyses, solutions for Ca2+-dependent activation, and model fitting are the same as described (36) and can be found in SI Materials and Methods. In experiments on Cd2+-dependent activation, the internal solution contained 150 mM KF, 20 mM Hepes, and 2 mM MgCl2 with either 0 or 100 μM CdCl2 as the 0 or 100 μM [Cd2+]i solution. CaF2 precipitates from the solution so that the solution contains no free Ca2+ (31, 32).

We modeled the conformation of Ca2+-bound RCK1 based on 3NAF (9) as follows. First, the RCK1 domain of 3NAF was separated from the rest crystal structure. Then, the three flexible segments around the D367 binding site were remodeled by sampling possible conformations using the LOOPY modeling program (37). To further construct a model for Ca2+-bound RCK1–RCK2 complex, the modeled Ca2+-bound RCK1 and the experimental Ca2+-bound RCK2 of 3MT5 (10) were docked together by using our protein-protein docking program MDockPP (38). The docked RCK1–RCK2 complex was further optimized/minimized by using Amber force fields (39). Thus, we obtained a modeled structure of two RCK domains of the BK channel, which contains two bound Ca2+ ions: one is at the Ca2+ bowl on RCK2, and the other is at the D367 site on RCK1. Specific details of the modeling can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The mSlo1 clone was kindly provided to us by Dr. Larry Salkoff (Washington University). Drs. Roderick MacKinnon and Youxing Jiang graciously provided coordinates for the structures of the CTD of BK channels. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL70393 (to J.C.) and R21GM088517 (to X.Z.). J.C. is the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Biomedical Engineering.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1010124107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial tone by activation of calcium-dependent potassium channels. Science. 1992;256:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1373909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gu N, Vervaeke K, Storm JF. BK potassium channels facilitate high-frequency firing and cause early spike frequency adaptation in rat CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 2007;580:859–882. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robitaille R, Charlton MP. Presynaptic calcium signals and transmitter release are modulated by calcium-activated potassium channels. J Neurosci. 1992;12:297–305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00297.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meredith AL, et al. BK calcium-activated potassium channels regulate circadian behavioral rhythms and pacemaker output. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1041–1049. doi: 10.1038/nn1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson NS, Robertson GA, Ganetzky B. A component of calcium-activated potassium channels encoded by the Drosophila slo locus. Science. 1991;253:551–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1857984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen KZ, et al. Tetraethylammonium block of Slowpoke calcium-activated potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes: Evidence for tetrameric channel formation. Pflugers Arch. 1994;426:440–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00388308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adelman JP, et al. Calcium-activated potassium channels expressed from cloned complementary DNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90160-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler A, Tsunoda S, McCobb DP, Wei A, Salkoff L. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science. 1993;261:221–224. doi: 10.1126/science.7687074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Yang Y, Ye S, Jiang Y. Structure of the gating ring from the human large-conductance Ca(2+)-gated K(+) channel. Nature. 2010;466:393–397. doi: 10.1038/nature09252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan P, Leonetti MD, Pico AR, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 2010;329:182–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber M, Salkoff L. A novel calcium-sensing domain in the BK channel. Biophys J. 1997;73:1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78168-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moss GW, Marshall J, Morabito M, Howe JR, Moczydlowski E. An evolutionarily conserved binding site for serine proteinase inhibitors in large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16024–16035. doi: 10.1021/bi961452k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao L, Kaldany C, Holmstrand EC, Cox DH. Mapping the BKCa channel's “Ca2+ bowl”: Side-chains essential for Ca2+ sensing. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:475–489. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia X-M, Zeng X, Lingle CJ. Multiple regulatory sites in large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 2002;418:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature00956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee US, Cui J. BK channel activation: Structural and functional insights. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian X, Niu X, Magleby KL. Intra- and intersubunit cooperativity in activation of BK channels by Ca2+ . J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:389–404. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweet T-B, Cox DH. Measurements of the BKCa channel's high-affinity Ca2+ binding constants: Effects of membrane voltage. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:491–505. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, et al. An epilepsy/dyskinesia-associated mutation enhances BK channel activation by potentiating Ca2+ sensing. Neuron. 2010;66:871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du W, et al. Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder. Nat Genet. 2005;37:733–738. doi: 10.1038/ng1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao L, Rapin AM, Holmstrand EC, Cox DH. Elimination of the BK(Ca) channel's high-affinity Ca(2+) sensitivity. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:173–189. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dudev T, Lim C. Principles governing Mg, Ca, and Zn binding and selectivity in proteins. Chem Rev. 2003;103:773–788. doi: 10.1021/cr020467n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui J, Cox DH, Aldrich RW. Intrinsic voltage dependence and Ca2+ regulation of mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:647–673. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui J, Aldrich RW. Allosteric linkage between voltage and Ca(2+)-dependent activation of BK-type mslo1 K(+) channels. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15612–15619. doi: 10.1021/bi001509+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horrigan FT, Aldrich RW. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:267–305. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui J, Yang H, Lee US. Molecular mechanisms of BK channel activation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:852–875. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8609-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox DH, Cui J, Aldrich RW. Allosteric gating of a large conductance Ca-activated K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:257–281. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, et al. Mg2+ mediates interaction between the voltage sensor and cytosolic domain to activate BK channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18270–18275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705873104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, et al. Activation of Slo1 BK channels by Mg2+ coordinated between the voltage sensor and RCK1 domains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1152–1159. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding MM. The architecture of metal coordination groups in proteins. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:849–859. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904004081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberhauser A, Alvarez O, Latorre R. Activation by divalent cations of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel from skeletal muscle membrane. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:67–86. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng XH, Xia XM, Lingle CJ. Divalent cation sensitivity of BK channel activation supports the existence of three distinct binding sites. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:273–286. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Sigworth FJ. Structure of the BK potassium channel in a lipid membrane from electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2009;461:292–295. doi: 10.1038/nature08291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun AP, Sy L. Contribution of potential EF hand motifs to the calcium-dependent gating of a mouse brain large conductance, calcium-sensitive K(+) channel. J Physiol. 2001;533:681–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi J, et al. Mechanism of magnesium activation of calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 2002;418:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee US, Cui J. beta subunit-specific modulations of BK channel function by a mutation associated with epilepsy and dyskinesia. J Physiol. 2009;587:1481–1498. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soto CS, Fasnacht M, Zhu J, Forrest L, Honig B. Loop modeling: Sampling, filtering, and scoring. Proteins. 2008;70:834–843. doi: 10.1002/prot.21612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang SY, Zou X. An iterative knowledge-based scoring function for protein-protein recognition. Proteins. 2008;72:557–579. doi: 10.1002/prot.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Case DA, et al. AMBER 11. San Francisco: Univ California; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.