Abstract

Precise control of alternative splicing governs oligodendrocyte (OL) differentiation and myelination in the central nervous system (CNS). A well-known example is the developmentally regulated expression of splice variants encoding myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), which generates two protein isoforms that associate with distinct cellular components crucial for axon-glial recognition during myelinogenesis and axon-myelin stability. In the quakingviable (qkv) hypomyelination mutant mouse, diminished expression of isoforms of the selective RNA-binding protein quaking I (QKI) leads to severe dysregulation of MAG splicing. The nuclear isoform QKI-5 was previously shown to bind an intronic element of MAG and modulate alternative exon inclusion from a MAG minigene reporter. Thus, QKI-5 deficiency was thought to underlie the defects of MAG splicing in the qkv mutant. Surprisingly, we found that transgenic expression of the cytoplasmic isoform QKI-6 in the qkv OLs completely rescues the dysregulation of MAG splicing without increasing expression or nuclear abundance of QKI-5. In addition, cytoplasmic QKI-6 selectively associates with the mRNA that encodes heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1), a well-characterized splicing factor. Furthermore, QKI deficiency in the qkv mutant results in abnormally enhanced hnRNPA1 translation and overproduction of the hnRNPA1 protein but not hnRNPA1 mRNA, which can be successfully rescued by the QKI-6 transgene. Finally, we show that hnRNPA1 binds MAG pre-mRNA and modulates alternative inclusion of MAG exons. Together, these results reveal a unique cytoplasmic pathway in which QKI-6 controls translation of the splicing factor hnRNPA1 to govern alternative splicing in CNS myelination.

Keywords: selective RNA-binding protein QKI, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1, myelin development, 3′-UTR, translation regulation

Myelination enables rapid conduction of nerve impulses and protects neuronal axons from extracellular insults, which is essential for the development and function of the central nervous system (CNS) (1). Oligodendrocytes (OLs) are responsible for CNS myelination, in which precise expression of OL-specific genes governs the formation and maintenance of CNS myelin (2, 3). Nearly all transcripts encoding myelin-specific structural proteins undergo extensive alternative splicing that is vigorously regulated during myelin development (4). As a result, the abundance of functionally distinct splice variants is markedly altered. A well-known example is the developmentally regulated alternative splicing of the pre-mRNA encoding myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), which generates two isoforms that are localized at the periaxonal membrane and mediate reciprocal signals toward axons and OLs (5). In rodents, exclusion of exon 12 generates the large MAG protein (L-MAG) predominantly expressed in the juvenile CNS, whereas inclusion of exon 12 introduces an in-frame stop codon, giving rise to the small MAG protein (S-MAG) mainly in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and mature CNS (5, 6). Both L-MAG and S-MAG share the same extracellular domains that signal toward axons to induce phosphorylation of neurofilaments, which is crucial for maintaining axon integrity (7–9). In contrast, the distinct intracellular C-termini in the MAG isoforms associate with different cytoplasmic components and signaling pathways in OLs (5, 10), which govern OL-axon recognition, myelination capacity, and organization of the node of Ranvier (11, 12). Interestingly, the unique C-terminal domain in L-MAG is specifically required for proper myelination in the CNS but not in the PNS (13). In addition, emerging evidence reveals dysregulation of L-MAG and S-MAG mRNAs in postmortem brains derived from patients with schizophrenia (14, 15), suggesting the functional importance of regulating MAG isoforms in cognitive function.

However, molecular mechanisms that control alternative splicing of MAG still remain poorly understood. In the homozygous quakingviable (qkv) hypomyelination mutant mouse, the selective RNA-binding protein quaking I (QKI) is specifically diminished in OLs (16) and the expression of MAG splice variants is severely dysregulated (17), suggesting that QKI plays important roles in controlling MAG splicing. Three major QKI protein isoforms are expressed in OLs as a result of alternative splicing of the QKI transcripts; they are called QKI-5, QKI-6, and QKI-7 based on the length (kilobases) of the corresponding mRNAs (18). Each QKI protein isoform harbors a distinct C terminus. QKI-5 carries a unique nuclear localization signal, predominantly localizes to the nucleus, and represses myelination (16, 19, 20). In contrast, the cytoplasmic isoforms QKI-6 and QKI-7 are essential factors for advancing OL maturation and myelin development (21, 22). A previous study has suggested that the nuclear QKI-5 is responsible for controlling alternative splicing of MAG, because QKI-5 can bind an intronic MAG sequence element in vitro and modulate alternative exon inclusion from a modified MAG minigene reporter (23). However, we are surprised to find that expression of the cytoplasmic isoform QKI-6 in OLs completely rescues the dysregulated alternative splicing of MAG pre-mRNA in the qkv mutant without increasing the expression or nuclear abundance of QKI-5. Furthermore, we show that the cytoplasmic QKI-6 specifically suppresses translation of the splicing factor heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1), which, in turn, modulates alternative splicing of MAG in myelination. These results identify a unique cytoplasmic pathway linking QKI-6 and hnRNPA1 function, which likely governs splicing of a broad spectrum of downstream RNA targets represented by MAG.

Results

Cytoplasmic Isoform QKI-6 Suppresses Inclusion of Exon 12 in MAG Pre-mRNA During CNS Myelin Development Without Increasing QKI-5 Function.

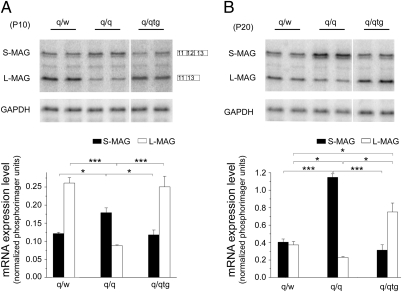

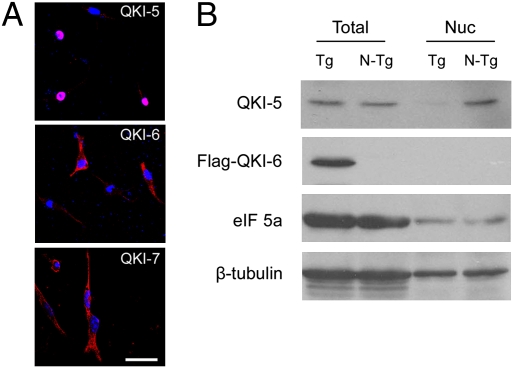

QKI-6 is the most abundant QKI isoform in CNS myelinogenesis, which is preferentially reduced in the homozygous qkv mutant (qkv/qkv), resulting in severe hypomyelination (24–26). Expression of a Flag-tagged QKI-6 transgene specifically in the cytoplasm of OLs largely rescues the reduction of QKI target mRNAs and the hypomyelination phenotype in the qkv/qkv mutant (24). To examine whether the QKI-6 transgene may also influence splicing, we developed an RNase protection assay (RPA) in which both the L-MAG and S-MAG mRNA isoforms can be detected simultaneously (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Dysregulation of MAG splicing was clearly detected in the qkv/qkv mutant, which was characterized by enhanced inclusion of exon 12 and reduced splicing toward exon 13, leading to overproduction of S-MAG and reduction of L-MAG as compared with that in the qkv/WT nonphenotypic controls (Fig. 1). Although such a splicing abnormality was previously predicted as a consequence of QKI-5 deficiency (23), we were surprised to find that the Flag–QKI-6 transgene, which is expressed specifically in the OL cytoplasmic compartment (24), completely rescued dysregulation of MAG splicing since early myelin development at postnatal day 10 (P10) (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, exon 12 inclusion was oversuppressed by Flag–QKI-6 at the peak of myelination (P20) (Fig. 1B), when the expression level of Flag–QKI-6 exceeded that of endogenous QKI-6 (24). The cytoplasmic localization of Flag–QKI-6, in contrast to the predominant nuclear localization of Flag–QKI-5, was further confirmed when expressed in the OL cell line CG4 (Fig. 2A). In addition, fractionation of brainstem homogenates indicated that Flag–QKI-6 was undetectable in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the Flag–QKI-6 transgene did not increase expression or nuclear abundance of QKI-5 (Fig. 2B). Instead, overexpression of Flag–QKI-6 in the cytoplasm reduced QKI-5 in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2B), most likely attributable to heterodimer formation between the cytoplasmic Flag–QKI-6 and the endogenous QKI-5 (19). These results suggest that QKI-6 is the primary QKI isoform that governs alternative splicing of MAG in CNS myelin development, which is independent of the previously reported activity of QKI-5 in modulating MAG splicing (23).

Fig. 1.

The Flag–QKI-6 transgene completely rescues dysregulated alternative splicing of MAG in the qkv/qkv (q/q) mutant. The RPA detects aberrantly increased S-MAG mRNA and decreased L-MAG mRNA in the q/q mutant as compared with the qkv/WT (q/w) nonphenotypic control at P10 (A) and P20 (B). Dysregulated MAG splicing was restored by introducing Flag–QKI-6 transgene into the q/q mutant (q/qtg) at both ages. (Upper) Representative phosphorimage of the RPA gel is shown. MAG mRNA splice variants are marked on the left. The alternative exons for each isoform mRNA are also indicated. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (Lower) Phosphorimager reading of the MAG isoform was normalized to that of the GAPDH mRNA and graphically displayed. P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA (n = 4). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001, Bonferroni's posttest.

Fig. 2.

Flag–QKI-6 is localized in the cytoplasmic compartment, and the Flag–QKI-6 transgene does not enhance QKI-5 expression or nuclear abundance. (A) Subcellular localization of Flag-QKI isoforms in the OL cell line CG4. Immunostaining of CG4 cells transfected with Flag-tagged QKI-5, QKI-6, and QKI-7 using the anti-Flag antibody (red) is shown. The DAPI staining (blue) marks nuclei. (B) Cytoplasmic expression of the Flag–QKI-6 transgene does not enhance QKI-5 expression or nuclear abundance. Nuclei were isolated from the brainstem of Flag–QKI-6 transgene (Tg) or nontransgene (N-Tg) adult mice. Whole-protein lysates (Total) and nuclear extracts (Nuc) of each mouse were analyzed by SDS/PAGE for QKI-5 and Flag–QKI-6 expression. The housekeeping proteins eIF5a and β-tubulin were used as loading controls.

QKI-6 Suppresses Translation of the hnRNPA1 mRNA and Rescues hnRNPA1 Overexpression in the qkv/qkv Mutant.

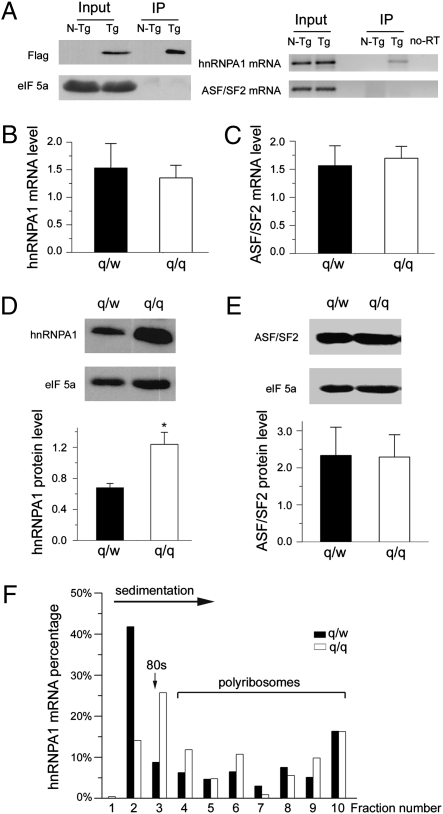

The predominant cytoplasmic localization of QKI-6 leads to the hypothesis that QKI-6 may regulate expression of splicing factors, which, in turn, controls alternative splicing of MAG in the nucleus during CNS myelination. Consistent with this idea, highly conserved QKI recognition elements (QRE, ACUAAY-N1-20-UAAY) are present in the 3′-UTRs of the mRNAs encoding hnRNPA1 and ASF/SF2 (Fig. S2A), two canonical splicing factors that often play opposing roles in alternative splicing (27, 28). Immunoprecipitation and RT-PCR analysis revealed that Flag–QKI-6 specifically expressed in brain OLs was associated with the hnRNPA1 mRNA (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the hnRNPA1 3′-UTR sufficiently mediated interactions with QKI-6 in transfected HEK293T cells, and removing the QRE completely abolished QKI binding (Fig. S2B). In contrast, the ASF/SF2 mRNA was not detected in Flag–QKI-6 complexes (Fig. 3A), despite the presence of a sequence motif that perfectly matches with the consensus QRE (Fig. S2A).

Fig. 3.

QKI binds hnRNPA1 mRNA and represses hnRNPA1 translation. (A) hnRNPA1 mRNA but not the ASF/SF2 mRNA associates with Flag–QKI-6 expressed in brain OLs. Cytoplasmic extracts prepared from the brainstem of Flag–QKI-6 transgene (Tg) and non-transgene (N-Tg) adult mice were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag M2 beads. (Left) Flag–QKI-6 in the input and immunoprecipitates (IP) was detected by immunoblot. (Right) RT-PCR analysis detected hnRNPA1 mRNA but not ASF/SF2 mRNA in the Flag–QKI-6 IP. hnRNPA1 mRNA (B) and ASF/SF2 mRNA (C) extracted from optic nerves of qkv/WT (q/w) and qkv/qkv (q/q) mice (n = 3) was quantified by qRT-PCR. hnRNPA1 (D) and ASF/SF2 (E) protein expression in the optic nerves of q/w and q/q mice was determined by immunoblot analysis. (Upper) Representative immunoblots are shown. eIF5a was used as a loading control. (Lower) Quantitative analysis was graphically displayed in the corresponding panels. *P < 0.05, standard t test (n = 5). (F) qRT-PCR analysis of polyribosome association of hnRNPA1 mRNA in q/w and q/q mice. The direction of sedimentation, 80S monoribosome, translating polyribosomes, and fraction numbers are indicated.

We next sought to determine whether and how QKI deficiency in the qkv/qkv mutant may affect expression of these splicing factors in OLs. Because QKI is not expressed in neurons and QKI deficiency is limited to OLs of the qkv/qkv mutant (16), we chose to quantify the ubiquitously expressed hnRNPA1 and ASF/SF2 in isolated optic nerves. OL proteins are highly enriched in such a preparation, but the preparation only contains negligible amounts of splicing factors expressed in neurons because they are restricted to the neuronal soma remotely located in the brain. Interestingly, despite the well-characterized role of QKI in controlling mRNA stability (21, 22, 26), QKI deficiency in the qkv/qkv mutant did not affect the levels of mRNA encoding either hnRNPA1 or ASF/SF2 (Fig. 3 B and C). Rather, the qkv/qkv mutant displayed abnormally elevated hnRNPA1 protein expression as compared with that in the nonphenotypic qkv/WT control (Fig. 3D). In contrast, expression of ASF/SF2 was not affected by QKI deficiency (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that translation of the hnRNPA1 mRNA is specifically enhanced in the OLs of the qkv/qkv mutant.

To test this hypothesis, we performed linear sucrose gradient fractionation, which is commonly used for assessing translation efficiency of endogenous mRNAs by measuring their ability to carry translating polyribosomes (29). The sedimentation of translationally repressed, ribosome-free ribonucleoprotein particles (mRNPs), the 80S monoribosome, and polyribosomes engaged in translation elongation was monitored by absorption at 254 nM as previously described (29). As shown in Fig. 3F, QKI deficiency in qkv/qkv mutant OLs caused a shift of the hnRNPA1 mRNA from translationally dormant mRNPs (fraction 2) into initiating 80S ribosome (fraction 3) and translating polyribosomes (fractions 4–10). This experiment suggests that deficiency of cytoplasmic QKIs results in abnormally enhanced translational initiation of the hnRNPA1 mRNA in the myelinating brain.

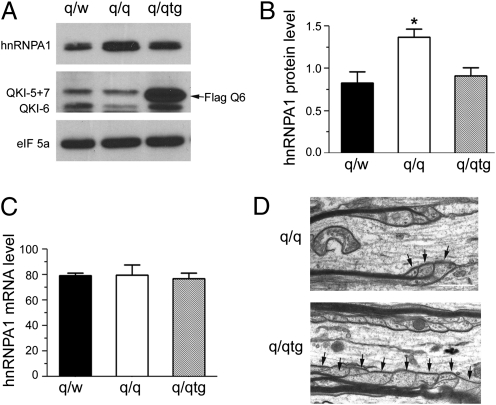

We further examined whether the Flag–QKI-6 transgene can suppress overexpression of hnRNPA1 in the qkv/qkv OLs. As shown in Fig. 4 A and B, Flag–QKI-6 successfully restored hnRNPA1 protein expression to normal levels in the qkv/qkv mutant that carries the transgene (q/q tg). In contrast, the Flag–QKI-6 transgene did not influence the expression of hnRNPA1 mRNA (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, accompanied by the rescue of dysregulated hnRNPA1 expression (Fig. 4 A and B) and MAG alternative splicing (Fig. 1), the abnormalities in organization and formation of paranodal loops on qkv/qkv axons were largely rescued by the Flag–QKI-6 transgene (Fig. 4D). Together, these results suggest that QKI-6 acts to suppress hnRNPA1 translation, which, in turn, controls alternative splicing and function of MAG in CNS myelin development.

Fig. 4.

The Flag–QKI-6 transgene reverts dysregulated hnRNPA1 protein expression and rescues abnormal paranodal loop formation. (A, Top) hnRNPA1 protein expression in the optic nerve of qkv/WT (q/w), qkv/qkv (q/q), and q/qtg mice by immunoblot. QKI pan-antibody detected down-regulation of all QKI isoforms in q/q mice as marked on the left, among which QKI-5 and QKI-7 comigrated in the upper band. (Middle) Overexpression of Flag–QKI-6 (arrow) in q/qtg mice. (Bottom) eIF5a was used as a loading control. (B) Quantitative analysis of hnRNPA1 protein expression based on normalization to eIF5a signal. P < 0.01, one-way anova (n = 5). *P < 0.05, Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. (C) hnRNPA1 mRNA expression level based on normalization to GAPDH (n = 3). (D) EM image showing a few paranodal loops (arrows) formed on the optic nerve of q/q mutant mice and a dramatic increase of paranodal loops as a result of expression of Flag–QKI-6 in q/qtg mice.

hnRNPA1 Binds MAG pre-mRNA to Modulate Alternative Splicing.

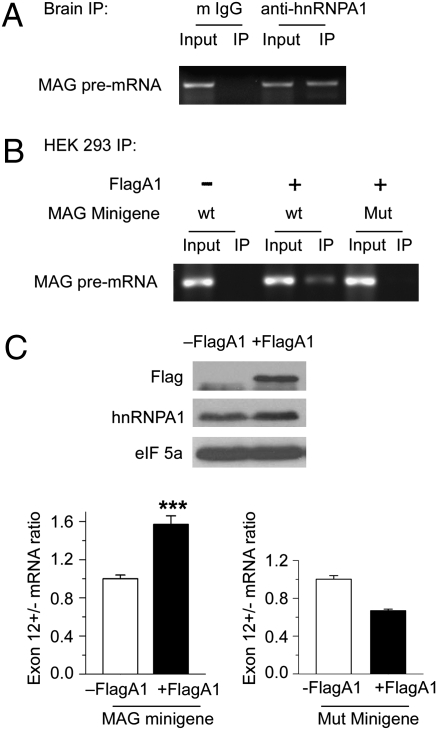

Finally, we tested whether increased hnRNPA1 expression as observed in the qkv/qkv mutant (Figs. 3 and 4) can indeed modulate alternative inclusion of MAG exons. We first examined whether hnRNPA1 associates with the endogenous MAG, pre-mRNA, in the brain. As shown in Fig. 5A, the OL-specific MAG pre-mRNA was clearly detected in the hnRNPA1 complexes immunoprecipitated from the brain by RT-PCR using a pair of primers spanning intron-exon boundaries at exon 13 of the MAG pre-mRNA (Fig. S3A). In addition, hnRNPA1 was associated with the pre-mRNA derived from a MAG minigene reporter in transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 5B), in which the intact genomic fragment sequence spanning exons 11 to 13 was fused to the C-terminal coding region of the EGFP (Fig. S3A). Interestingly, we found an RNA element in exon 13 that contains core consensus sequences for hnRNPA1 binding (Fig. S3A). Replacement of individual nucleotides in this predicted hnRNPA1 binding element completely abolished interaction between hnRNPA1 and the MAG minigene reporter pre-mRNA (Fig. 5B). Importantly, forced expression of exogenous Flag-hnRNPA1 resulted in a significant increase in the ratio of the reporter mRNA that carries exon 12 to the one that lacks exon 12 (Fig. 5C) based on quantitative (q) RT-PCR analysis using isoform-specific primers illustrated in Fig. S3 B and C. Moreover, mutation of the hnRNPA1 binding sites in exon 13 abolished such an effect by Flag-hnRNPA1 on exon 12 inclusion (Fig. 5C). These results clearly indicate that elevated expression of hnRNPA1 modulates alternative splicing of MAG exons by interacting with the pre-mRNA and enhancing exon 12 inclusion, which recapitulates the observed dysregulation of MAG in the qkv/qkv mutant. Thus, the abnormally increased hnRNPA1 expression in the qkv/qkv mutant, as a result of lacking QKI-6–mediated translation suppression, is an underlying mechanism for the dysregulation of MAG splicing in CNS myelination.

Fig. 5.

hnRNPA1 binds MAG pre-mRNA and modulates alternative inclusion of MAG exons from a minigene reporter. (A) Endogenous hnRNPA1 associates with MAG pre-mRNA. Protein lysates prepared from UV cross-linked WT brainstem were immunoprecipitated using anti-hnRNPA1 or mouse-IgG (m IgG) as a negative control. Endogenous MAG pre-mRNA in the input and immunoprecipitates (IP) was detected by RT-PCR. (B) hnRNPA1 associates with MAG exon 13 in the reporter pre-mRNA. Protein lysates were prepared from UV cross-linked HEK293T cells coexpressing Flag-tagged hnRNPA1 (FlagA1) with WT (wt) or mutant MAG minigene reporter in which the hnRNPA1 site was abolished (Mut). Lysates were also prepared from cells expressing WT MAG minigene alone. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-Flag M2 beads, followed by RT-PCR to detect the reporter pre-mRNA. (C) hnRNPA1 modulates alternative inclusion of MAG exons. (Upper) Representative immunoblot using lysates from Flag-hnRNPA1–transfected (+FlagA1) or vector-alone–transfected (−FlagA1) HEK293T cells is shown. (Lower) Ratio of reporter mRNA isoform that carries or lacks exon 12 derived from the WT or mutant MAG minigene with or without expressing Flag-hnRNPA1 is shown. ***P < 0.001, t test.

Discussion

Our studies provide clear evidence that the cytoplasmic isoform QKI-6 can regulate alternative splicing of MAG pre-mRNA in CNS myelination by controlling translation of the splicing factor hnRNPA1, independent of the previously proposed function of the nuclear isoform QKI-5 (23). These results identify a previously undescribed mechanism for cytoplasmic QKI isoforms to control pre-mRNA processing, which, in turn, governs CNS myelin development. Given the universal expression of hnRNPA1 and the numerous targets under hnRNPA1-mediated splicing control (30), the cytoplasmic pathway connecting QKI and hnRNPA1 function can be predicted to regulate a broad spectrum of downstream genes, represented by the alternative splicing of MAG in CNS myelination.

The functional impact of QKI on mRNA splicing has long been recognized, because many myelin protein mRNA splice variants are dysregulated as a result of QKI deficiency in the qkv mutant (4, 31). Based on the distinct distribution of QKI isoforms in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (16), the nuclear isoform QKI-5 was predicted to control pre-mRNA splicing (23, 31), whereas the cytoplasmic QKI isoforms were shown to govern mRNA stability in OL and myelin development (21, 22, 24, 25). A recent report identified a large number of intronic QKI-5 binding sites in the human transcriptome by cross-link immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (32), supporting the idea that QKI-5 likely regulates splicing of its RNA targets. Indeed, QKI-5 was able to bind an intronic RNA element located downstream of MAG exon 12 in vitro and to inhibit inclusion of MAG exon 12 from a modified minigene reporter in transfected HeLa cells (23). Thus, deficiency of QKI-5 is a contributing mechanism to the aberrantly increased inclusion of MAG exon 12 in the qkv/qkv mutant. In addition, because QKI-6 and QKI-7 share similar mRNA target selectivity (33), deficiency of the cytoplasmic QKI-7 in the qkv/qkv mutant likely contributes to the aberrantly increased expression of hnRNPA1 and dysregulation of MAG splicing, although QKI-7 is expressed at a much lower level than QKI-6 in myelinating OLs. However, our data clearly demonstrate that the Flag–QKI-6 transgene can completely rescue the abnormally elevated hnRNPA1 expression and the enhanced inclusion of MAG exon 12 in the qkv/qkv mutant without increasing QKI-5 expression or nuclear abundance. These results argue that QKI-6 plays a predominant role in governing alternative splicing of MAG in CNS myelination, independent of other QKI isoforms, by regulating cytoplasmic target mRNAs that encode splicing factors. This idea is supported by the presence of QREs (34) in the 3′-UTR of mRNAs that encode a number of well-characterized splicing factors (35), among which hnRNPA1 and ASF/SF2 are of particular interest considering their opposing functional influence on alternative splicing (27, 28) and the vigorous developmental regulation of hnRNPA1 during OL differentiation (36). Indeed, we found that the 3′-UTR of hnRNPA1 is sufficient for mediating interactions with Flag–QKI-6 in a QRE-dependent manner (Fig. S2). In contrast, despite the presence of highly conserved QREs in the ASF/SF2 3′-UTR, the ASF/SF2 mRNA is not associated with Flag–QKI-6 in brain OLs. Moreover, expression of ASF/SF2 is not affected by QKI deficiency. Therefore, despite the fact that QREs can directly interact with QKI (32, 34, 37), the presence of a QRE is not sufficient for QKI association in vivo. Other RNA-binding proteins that can bind sequence elements near the QRE must modulate QKI interaction with QREs, perhaps in a cell type-specific manner.

In addition to the well-characterized function of QKI in controlling mRNA stability in OLs and CNS myelin development (21, 22, 26), QKI-6 was reported to suppress translation of reporter in vitro and in transfected cells (38, 39), although no direct evidence has demonstrated the role of QKI as a translation suppressor in vivo in mammals. In the qkv/qkv mutant, deficiency of QKI leads to increased expression of hnRNPA1 protein without affecting the level of hnRNPA1 mRNA (Fig. 3), suggesting that hnRNPA1 is a target for QKI-mediated translation suppression. Indeed, a reduction of hnRNPA1 mRNA in translationally dormant mRNPs was observed in the qkv/qkv mutant, which was accompanied by an increase of the hnRNPA1 mRNA in translating ribosomes. This experiment suggests enhanced hnRNPA1 translation initiation as a result of QKI deficiency. Despite the fact that QKI-6 can bind the hnRNPA1 3′-UTR, the possibility that QKI may also suppress hnRNPA1 translation in CNS myelination through indirect mechanisms by regulating other QKI targets cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, OL-specific expression of the Flag–QKI-6 transgene is sufficient for suppressing the abnormally elevated hnRNPA1 protein expression in the qkv/qkv mutant without affecting expression of hnRNPA1 mRNA (Fig. 4). Moreover, we showed that hnRNPA1 can bind MAG pre-mRNA in vivo and in cultured cells and that overexpression of hnRNPA1 modulates alternative exon inclusion from a MAG minigene reporter (Fig. 5), recapitulating the dysregulated alternative splicing of MAG in the qkv mutant (Fig. 1). Together, these data suggest that cytoplasmic QKI-6 acts as a translation suppressor for hnRNPA1 mRNA during CNS myelination, which governs balanced hnRNPA1 protein expression to control alternative splicing of downstream targets, represented by the MAG pre-mRNA.

hnRNPA1 is a well-known splicing suppressor, which often acts to bind exon splicing silencers near the target exon, thus preventing access by the splicing machinery (40, 41). The aberrant overexpression of hnRNPA1 in the qkv/qkv mutant suppresses production of the L-MAG mRNA that is derived from selective splicing toward exon 13 and skipping exon 12. This is accompanied by a reciprocal increase of S-MAG mRNA as a result of enhanced exon 12 inclusion. One possible mechanism by which hnRNPA1 may modulate alternative splicing of MAG is by partially suppressing selective splicing toward exon 13, which, in turn, leads to favorable splicing toward exon 12. Consistent with this idea, mutation of the predicted hnRNPA1 site in exon 13 abolishes binding of hnRNPA1 to the pre-mRNA containing MAG exons and the effects of hnRNPA1 in promoting exon 12 inclusion (Fig. 5). However, because hnRNPA1 is also known to modulate micro-RNA expression (42), whether the aberrantly increased hnRNPA1in the OLs of the qkv/qkv mutant may also modulate MAG mRNA isoform expression via micro-RNA–mediated mechanisms is an intriguing possibility to be explored in the future. It is important to mention that although the qkv/qkv mutant allowed us to identify overexpression of hnRNPA1 as a contributing mechanism for dysregulation of MAG splicing, considering the complexity of the exon recognition process, hnRNPA1 must cooperate with other splicing factors, likely including both splicing suppressors as well as splicing enhancers. Whether QKI may also regulate expression of additional splicing factors that cooperate with hnRNPA1 to control splicing is the next challenge for future studies.

Numerous OL transcripts are subjected to developmentally programmed regulation of alternative splicing (3), many of which are dysregulated in the qkv/qkv mutant that harbors deficiency of all QKI isoforms (31, 43). The full capacity of functional targets for the nuclear QKI-5 and the cytoplasmic QKI-hnRNPA1 pathway that govern CNS myelination still remains elusive. The fact that QKI isoforms are reduced in postmortem brains derived from patients with schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders (14, 43, 44) raises an intriguing question of whether and how dysregulation of splicing attributable to QKI-pathway deficiency may contribute to cognitive impairment. Importantly, both QKI and hnRNPA1 are broadly expressed in many cell types in addition to myelinating OLs. The frequent mutations at the QKI locus (30) and the abnormal overexpression of hnRNPA1 found in human glioma cell lines and tumor specimens (45) suggest the possibility that the QKI-hnRNPA1 pathway we identified may also play important roles in normal cell growth as well as in tumorigenesis via controlling pre-mRNA splicing.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The qkv colony (Jackson Laboratory), the Flag–QKI-6 transgenic mice, and transgenic rescue of the qkv/qkv mutant were described previously (24). Animal treatment was according to National Institutes of Health regulations under the approval of the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis.

Generation of the MAG minigene reporter, site-directed mutagenesis, and construction of the hnRNPA1 3′-UTR reporters are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

CG4 cells were raised as previously described (22). PCDNA (PC)–Flag–QKI-5, PC–Flag–QKI -6, and PC–Flag–QKI -7 (33) were transfected using a Nucleofector kit optimized for OLs (Amaxa, Inc.). HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and transfected with 0.5 μg of MAG minigene with or without 1 μg of Flag-hnRNPA1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 18 h.

RNA Preparation and RPA.

RNA extraction, RPA probe synthesis, and RPA analysis were performed using previously published procedures (26) and are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Nuclear Fractionation and Western Blot Analysis.

Nuclei were isolated from the brainstem as previously described (26). Equal amounts of protein samples were separated on 12.5% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE. Anti-hnRNPA1 (1:5,000) and anti-Flag M2 (1:3,000) were purchased from Sigma; anti-ASF/SF2 (1:1,000) was purchased from Invitrogen; anti-eIF5α (1:10,000) and anti-β-tubulin (1:10,000) were purchased from Santa Cruz; and anti-QKI-pan and QKI-5 antibody were produced by NeuroMab.

UV Cross-Linking Immunoprecipitation and RT-PCR.

Brainstem was minced and UV was cross-linked using a Stratalinker (Stratagene, 360 mJ). The tissue homogenates were lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor, and RNase inhibitors. Anti-Flag M2 beads (Sigma) or anti-hnRNPA1 antibody conjugated to protein A beads was used for immunoprecipitation as previously described (24). Transfected cells were also UV cross-linked before immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitated complexes were subjected to RNA extraction followed by RT-PCR as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Sucrose Gradient Fractionation.

Cytoplasmic extracts from brainstems of P20 q/w and q/q mice were processed for linear sucrose gradient fractionation (15–45%, wt/vol) as previously described (29). Total RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed to determine the percentage of hnRNPA1 mRNA in each fraction.

Immunocytochemistry and EM Analysis.

Cells were fixed and blocked with 2% (wt/vol) normal goat serum as previously described (22) and incubated with anti-Flag antibody (1:1,000; Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. Texas red-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Fluorescent images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscopic imaging system. EM analysis was carried out as previously described (24).

Statistical Analysis.

All error bars indicate SEM. Student's t test was used for two-sample comparisons. For multiple-sample comparisons, one-way or two-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Martin Holcik (University of Ottawa, Canada) for the generous gift of Flag-hnRNPA1 expression construct and Andrew Bankston for critical comments on the manuscript. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 NS056097A, National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) Grant RG4010-A-2, and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Independent Investigator Award (to Y.F.); a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (to L.Z.); and National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 GM008367 (to M.D.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.L.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1007487107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nave KA, Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:535–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons M, Trotter J. Wrapping it up: The cell biology of myelination. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campagnoni AT, Macklin WB. Cellular and molecular aspects of myelin protein gene expression. Mol Neurobiol. 1988;2:41–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02935632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campagnoni AT. Molecular biology of myelin proteins from the central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1988;51:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb04827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quarles RH. Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG): Past, present and beyond. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1431–1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachner M, Bartsch U. Multiple functions of the myelin-associated glycoprotein MAG (siglec-4a) in formation and maintenance of myelin. Glia. 2000;29:154–165. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(20000115)29:2<154::aid-glia9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dashiell SM, Tanner SL, Pant HC, Quarles RH. Myelin-associated glycoprotein modulates expression and phosphorylation of neuronal cytoskeletal elements and their associated kinases. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1263–1272. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen T, et al. Axonal protective effects of the myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Neurosci. 2009;29:630–637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5204-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan B, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein and complementary axonal ligands, gangliosides, mediate axon stability in the CNS and PNS: Neuropathology and behavioral deficits in single- and double-null mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marta CB, et al. Myelin associated glycoprotein cross-linking triggers its partitioning into lipid rafts, specific signaling events and cytoskeletal rearrangements in oligodendrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:35–46. doi: 10.1017/s1740925x04000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pernet V, Joly S, Christ F, Dimou L, Schwab ME. Nogo-A and myelin-associated glycoprotein differently regulate oligodendrocyte maturation and myelin formation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7435–7444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0727-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biffiger K, et al. Severe hypomyelination of the murine CNS in the absence of myelin-associated glycoprotein and fyn tyrosine kinase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7430–7437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07430.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita N, et al. The cytoplasmic domain of the large myelin-associated glycoprotein isoform is needed for proper CNS but not peripheral nervous system myelination. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1970–1978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01970.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aberg K, Saetre P, Jareborg N, Jazin E. Human QKI, a potential regulator of mRNA expression of human oligodendrocyte-related genes involved in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7482–7487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601213103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCullumsmith RE, et al. Expression of transcripts for myelination-related genes in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy RJ, et al. Neural cell type-specific expression of QKI proteins is altered in quakingviable mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7941–7949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07941.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita N, et al. Developmentally regulated alternative splicing of brain myelin-associated glycoprotein mRNA is lacking in the quaking mouse. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebersole TA, Chen Q, Justice MJ, Artzt K. The quaking gene product necessary in embryogenesis and myelination combines features of RNA binding and signal transduction proteins. Nat Genet. 1996;12:260–265. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J, Zhou L, Tonissen K, Tee R, Artzt K. The quaking I-5 protein (QKI-5) has a novel nuclear localization signal and shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29202–29210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larocque D, et al. Nuclear retention of MBP mRNAs in the quaking viable mice. Neuron. 2002;36:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larocque D, et al. Protection of p27(Kip1) mRNA by quaking RNA binding proteins promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:27–33. doi: 10.1038/nn1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, et al. QKI binds MAP1B mRNA and enhances MAP1B expression during oligodendrocyte development. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4179–4186. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu JI, Reed RB, Grabowski PJ, Artzt K. Function of quaking in myelination: Regulation of alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4233–4238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072090399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao L, Tian D, Xia M, Macklin WB, Feng Y. Rescuing qkV dysmyelination by a single isoform of the selective RNA-binding protein QKI. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11278–11286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2677-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Z, et al. The quakingviable mutation affects qkI mRNA expression specifically in myelin-producing cells of the nervous system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4616–4624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Zhang Y, Li D, Feng Y. Destabilization and mislocalization of myelin basic protein mRNAs in quaking dysmyelination lacking the QKI RNA-binding proteins. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4944–4953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04944.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cáceres JF, Stamm S, Helfman DM, Krainer AR. Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science. 1994;265:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.8085156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayeda A, Helfman DM, Krainer AR. Modulation of exon skipping and inclusion by heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 and pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2/ASF. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2993–3001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu R, et al. The fragile X protein controls microtubule-associated protein 1B translation and microtubule stability in brain neuron development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15201–15206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404995101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He Y, Smith R. Nuclear functions of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A/B. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1239–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy RJ. Molecular defects in the dysmyelinating mutant quaking. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:417–422. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980215)51:4<417::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafner M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of QKI mediates developmental signals to regulate mRNA metabolism. EMBO J. 2003;22:1801–1810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galarneau A, Richard S. Target RNA motif and target mRNAs of the Quaking STAR protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:691–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McInnes LA, Lauriat TL. RNA metabolism and dysmyelination in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang E, Dimova N, Cambi F. PLP/DM20 ratio is regulated by hnRNPH and F and a novel G-rich enhancer in oligodendrocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4164–4178. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryder SP, Williamson JR. Specificity of the STAR/GSG domain protein Qk1: Implications for the regulation of myelination. RNA. 2004;10:1449–1458. doi: 10.1261/rna.7780504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lakiza O, et al. STAR proteins quaking-6 and GLD-1 regulate translation of the homologues GLI1 and tra-1 through a conserved RNA 3’UTR-based mechanism. Dev Biol. 2005;287:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saccomanno L, et al. The STAR protein QKI-6 is a translational repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12605–12610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goina E, Skoko N, Pagani F. Binding of DAZAP1 and hnRNPA1/A2 to an exonic splicing silencer in a natural BRCA1 exon 18 mutant. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3850–3860. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02253-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kashima T, Rao N, David CJ, Manley JL. hnRNP A1 functions with specificity in repression of SMN2 exon 7 splicing. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3149–3159. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guil S, Cáceres JF. The multifunctional RNA-binding protein hnRNP A1 is required for processing of miR-18a. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:591–596. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bockbrader K, Feng Y. Essential function, sophisticated regulation and pathological impact of the selective RNA-binding protein QKI in CNS myelin development. Future Neurol. 2008;3:655–668. doi: 10.2217/14796708.3.6.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sokolov BP. Oligodendroglial abnormalities in schizophrenia, mood disorders and substance abuse. Comorbidity, shared traits, or molecular phenocopies? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:547–555. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clower CV, et al. The alternative splicing repressors hnRNP A1/A2 and PTB influence pyruvate kinase isoform expression and cell metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1894–1899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914845107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.